MIXER’S JOB

This is where the rubber meets the road. The system is loaded in and now you have to figure out how to mix the show. No matter how hard you think it has been getting to this point, the easy part is now behind you. Now you have to mix a show on very little sleep and you will have to apologize for every missed pickup. If you miss too many pickups, the designer will find himself pulled aside to ask what the problem is with the mixer. Most directors have a very low tolerance for missed pickups. They can forgive a horrible mix as long as the correct mics were always open. This is of course a major challenge when you are learning the show and the timing of the actors. It is at this point where the mixer has to size up what the designer expects. Usually a conversation about what the designer considers the mixer’s responsibility is a good idea. There are some designers who want no input from the mixer. This type of designer does not want to know what the mixer thinks about the sound and does not want any advice on what to do. This type of designer just wants the mixer to mix the DCAs (or VCAs or Control Groups). Some designers want input from the mixer but prefer to make the final decisions. This type of designer wants the mixer to tell him what he thinks of a certain EQ or reverb. This type of designer, similarly, wants the mixer to just mix, but he expects the mixer to give him feedback about how it is to mix on the system. This type of designer will stand close to the mixer and work as his extra hands. The mixer can say, “I need more gain on Steve.” Or, “Can you work on the hat EQ on Tom during this next scene?” Then the designer can work with the mixer to make adjustments while the mixer focuses on not missing pickups. There are some designers who prefer to let the mixer take care of gain and EQ. This type of designer will EQ and balance the system and then leave it to the mixer to make adjustments to individual actors.

It is crucial to know what the designer expects. The last thing you want to do is to start adjusting EQs if you are working with a designer who thinks EQ is off limits to the mixer. You also don’t want to avoid touching the EQ even if it sounds awful because you are waiting for the designer to fix it. Once you add the band in, you have to find out the expectations for the band as well. Some designers may expect one thing when it comes to voices and something completely different when it comes to instruments. It is very common for designers to work with mixers to find a range for them to mix in. The designer may ask you to mix the vocals at –10 during the dialogue scenes. While you do that, the designer can make adjustments to the Matrix settings to allow –10 to be the level the designer wants. From that point on, it is easy for the designer to talk to the mixer about level. The same holds true for the music.

When you are going through tech it is a test of your focus. Your job is to throw faders and not miss pickups, no matter what is going on around you. It is a hard concept to master. As you are mixing, you may have two or three people working on the board at the same time. They could be grabbing knobs and pushing buttons and doing who knows what. Your job is to focus on the actors. If a designer needs something from you, or for you to get out of the way, he will tell you. More than anything the designer wants to shape the sound while you mix with a consistent mix. I have worked with many young mixers and it takes them time to understand that I will let them know if I need something and to ignore me. Inevitably I will go to grab an EQ and the mixer will pull his hands off the desk and stop mixing. Rule number one as a mixer is that you never take your hands off the faders. Never. After I repeatedly say, “Keep mixing, ignore me,” the mixer will finally get it and just mix so I can work.

The script is by far the most important tool to a mixer. Not a drill. Not a crescent wrench. Not a Cricket. A script is king. Without a script you have no clue what is going to happen. If you are lucky you will have seen a run-through before tech started so you will be sight-mixing. I consider mixing to be similar to playing an instrument, and sight-mixing is just like sight-reading music. Of course sight-reading music is easier because the notes are always in the same place and the music has a standardized look, so you have a shot. With a musical you have to program your instrument so the correct mics show up and are turned on at the right time. Without an accurate script, there is no chance of being able to mix a show.

There are a lot of strong opinions about script mixing in this business. Everyone knows it is necessary, but a lot of macho bravado goes along with not mixing with a script. There are mixers who get “off-book” as fast as they can and take pride in the fact that they were mixing without a script after the first run-through. I have worked with mixers who will give you a hard time if you mix with a script. I have also worked with some great mixers who have nothing to prove and will mix with a script in front of them for years. The reality is that the audience doesn’t care if you mix with a script or not, as long as it sounds good. The director doesn’t care either. In fact, no one other than sound people care. Some sound people are convinced they mix better without a script. I think that is a very valid point. I know there are scenes I have mixed that never worked until I got off-book on them. But I am not a fan of insisting that people mix better one way over another, or by demanding that people get off-book. This is something you will have to figure out for yourself. I have worked with people who insisted I get off-book, and I had a miserable time learning the show, and I have worked with people who didn’t care and I had no problem learning the show. What is important is to find out what you need as a mixer and don’t let people tell you what is the right way, because there is no one right way on this topic.

One very good reason for using a script is to document the mix so it is repeatable. Personally, I don’t see any other way to document a mix. At one time I subbed on four Broadway musicals. I would mix between six and eight shows a week on four different shows. When I learn to sub on a show, I am meticulous with my script. I don’t push a button or move a fader unless it is notated in my script. I also make level notations for almost every line in the show. Beside a character name I will put a note that says something like “@–10” to let me know that is approximately where I should throw the fader. I think that is crucial for a sub to be able to come in once or twice a week and mix the show consistently with the way it is always mixed. When I was bouncing around these four shows, there was no way I could’ve remembered some of the details to the mix of these shows without the scripts. This is not to say that I do not alter the mix if needed. One of the big fears non-script mixers have is that you are just going to mix by the numbers. That is not the case. There are a lot of constants in mixing. I know that a song starts at –10 and bumps to 0. I know a reverb needs to be preset to –7.5. There is a lot I can document and follow when I mix. If I don’t document that, I may end up drifting from those settings, which are what the designer set. But I can always listen to the show and realize that there is a sub trumpet player that is screaming loud and adjust. Also, if I set a song at –10 week after week for months and then all of a sudden one night –10 is really quiet, then I know something is wrong.

I once got into a debate about script-mixing with British sound designer Mick Potter. Mick designed Bombay Dreams and Lady in White on Broadway. I was the sub mixer on Bombay Dreams. Mick also re-designed The Phantom of the Opera and I was hired to build the system and install it and supervise the change over and the sound of the show after it re-opened. One day we were standing in the Majestic Theater at the new mix position for Phantom, which has been running for more than 20 years and has crew and musicians and cast who have been on the show from the beginning. Mick was explaining that he did not believe in using a script ever when mixing. In England it is common for the mixer to be in rehearsals with the cast for months mixing the rehearsals, which makes it easier to move into tech and not need a script. Mick believed that you have to feel the mix and if you are reading a script there is no way to feel it. I said I thought it was possible to achieve that while mixing with a script, which he adamantly disagreed with.

Recently he told me that he went back to hear one of his shows after several months and was unhappy with how the mix had drifted. I said maybe that wouldn’t happen if there was some documentation of the mix. He disagreed and then explained that mixing was like playing music, and music always sounds better when musicians put down the music and just play from the heart. Jokingly I said I agreed with him, and to prove his point I was going to go into the pit and take the 20-year-old handwritten sheet music away from all of the musicians in the pit just to hear how they sounded.

When you work on a show you will usually be given a copy of the script in a Word file from stage management. Sometimes all you are given is a hard copy. As a mixer there is a lot of information you just don’t need in a script, and the less text on the page the easier it is to read. Most of the stage directions are worthless to a mixer. The mixer doesn’t care that Steve crosses downstage and picks up a gun. So one of the first things to be done is to go through and delete any extraneous text or blank space. But wait, before you do that, you need to think about pagination.

The script will most likely have a footer with an automatic page number on every page. If you go through and chop up the script your page numbers will not match the stage manager’s script. This can make tech miserable. Just imagine trying to quickly find where they are starting from and the SM says page 58 and for you it is page 46. So, the first thing to do is to resolve the pagination issue. The only way to do this is to start on the last page in the script and put the page number in the body of the script. I usually put it on its own blank line at the top of the page aligned to the right. Work backwards until you get to the first page and then delete the footer page numbers. Now as you go through and alter the script you will end up having page numbers that are accurate but not necessarily on the top or bottom of the page. It is possible to have two or three page numbers on a single page if you end up cutting a lot.

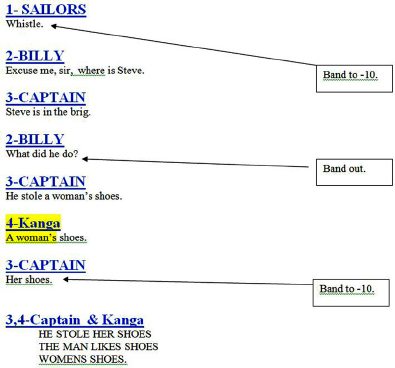

After cutting this extra stuff I tend to make a “Style” for different aspects of the script. I will make a Style for “Character Names” and one for “Scene Titles” and one for “Song Titles.” Then I will go through the script and assign everything to the proper Style. Once I do that I can easily select all items of a certain Style and make it look like I want it to. I personally like my character names aligned left and larger than the dialogue. I also usually make them a color that pops out so it is easier for me to read and I underline it. Once I have done that, I will go through and add DCA numbers for every Character name. I will also highlight yellow things that I think will sneak up on me. If there is a scene with two people for a couple of pages and then suddenly someone else enters, I know I have a tendency to miss that entrance, so I will highlight that person’s line. I will then start adding boxes with cue numbers and notes on the right side. My script will continue to grow through tech. Eventually I will hand it off for my sub to learn. I will show him how to quickly reformat things to his liking and let him make it his script.

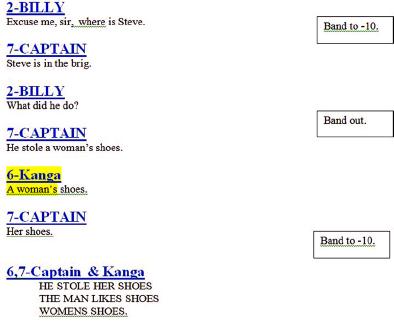

Figure 15.1. A script of a fake show the way I lay it out.

In the olden days of analog mixing, we had something called VCAs on large format desks. A VCA is a voltage controlled attenuator. This is a fader that you can assign multiple faders to and it works like a master fader. A VCA is different from a Sub-Group in that you cannot send the VCA signal anywhere. Instead the VCA is controlling the level of the channel faders, but you still independently send the channel faders to Auxes or Mixes or Sub-Groups. A VCA is a crucial element to mixing. VCAs allow us to assign all of the men to one fader even though half of the men go to Group 1 and the other half go to Group 2. By using VCAs we can create a logical and manageable area on the board to mix the show.

Once we moved into the world of digital consoles, the term VCA was no longer accurate. A VCA was actually controlling the amount of voltage allowed to the inputs in its group to adjust the volume of those inputs. The digital world is not dealing with voltage on the input level. When Yamaha released the PM1D in 2000 they introduced the DCA or digitally controlled attenuation. Other digital consoles have come along and introduced their version of the digital VCA and have given them other names. Control Groups is another popular digital interpretation of the analog VCA. Whatever term is used, the basic function is essentially the same. Don’t be shocked if you hear an oldschool guy like me talk about doing the VCA programming while working on a DiGiCo’s Control Groups. For simplicity I will be using the term DCA for the rest of this chapter, since most of the boards are digital now. You can adapt it to whatever style console you have. Whether you are using a Cadac with VCAs or a DM1000 with Master Control Groups, the ideas are the same.

A majority of mixing on Broadway is considered DCA mixing. We mix almost everything using the DCAs. If we leave the DCA section and grab something at the input level it is sometimes called “board mixing.” One reason for mixing on the DCAs is to make something complicated easier, but another main reason is to leave a majority of the board open for the design team to work. If you are mixing on the input faders, it will restrict where the designer can go to make adjustments. Most designers want the ability to make adjustments to the input levels that can be stored for a song. Think about a song with 30 people singing and a band of 24 playing. The designer will want the mixer sitting calmly in the middle of the board mixing something like two DCAs, one for men and one for women, and also one or more faders for the band. Then the designer can move around the board and solo different inputs and work on a balance of all the vocals and band. The designer can make adjustments to the inputs and then the mixer can save that snapshot so it can be recalled night after night. The mixer’s job is simplified and repeatable. He puts the faders at –10 and mixes, but the inputs are all over the place to make it sound balanced.

In order to program DCAs for a show you need to understand some basic philosophies involved. Consistency is very important in DCA programming. You want to make decisions about the programming that can be repeated throughout the show. You may decide that DCA 7 will be Men and DCA 8 will be Women. If that is the case, then you will want to repeat that every time you need a Men and Women fader. If you switch them in one cue, it is possible that you will bring up the wrong fader at the wrong time.

The first thing to think about when planning your DCAs is how you are going to treat your band. Will the band be one DCA or more DCAs? Will the band reverb return input be a separate DCA or will it be in the Band DCA? Different mixers like different things. There is no right or wrong here. Some mixers like breaking the band up into sections on the DCAs so they have some individual control from the DCA section. Typically the band is on the right side of the DCA section, or the higher numbers. In this style you will see something like DCA12-Band, DCA11-Drums, DCA10-Solo. When used, the Solo DCA is a place reserved for instruments that may need to be pushed out for solos. When mixing on this style of programming you typically push all three DCAs as one and occasionally push or pull different DCAs to texture the mix. Other mixers prefer to keep the band simpler and just have a Band DCA. This can make mixing easier in some ways but more complicated when you need to push solo instruments out. Sometimes the way you do the band is dependent on how many DCAs you have. If you only have eight DCAs, then you probably don’t want to waste three or four of them on the band, or you might not have enough to mix the rest of the show.

Once you have figured out the band you can move on to the vocals. The general idea is to find an easy way to mix something complicated. Most of the time mixers will put big block numbers above DCAs so when they look down they see numbers and they can just throw the numbers, as it is called. If you look back at Figure 15.1 you will see DCA numbers by each Character name. I gave those numbers for very specific reasons to make the scene easy to mix. When I mix that scene I can look down at the board and mix the pattern. 1, 2, 3, 2, 3, 4, 3, 3&4.

Of course while I mix that scene I have to put the band at –10 for a percussion sound, then take the band out and then preset it for the song. Because of the speed of this show I went with the band on one DCA because I couldn’t manipulate three DCAs during this quick dialogue. We take the band out every chance we get, because 50 open mics do not do much to make your show sound good and inevitably you are going to hear the musician bang something. I was the US Associate, or United States Sound Design Associate, on a tour and the mixer parked the band at –10 for the entire show. It sounded awful. There were 20-minute dialogue scenes with no music playing and yet he left all the band mics wide open. He actually went to the conductor and told him that the musicians needed to be quiet because they could be heard blowing their noses in the house. I suggested he take the band fader out and he refused. He didn’t last long.

Figure 15.2. A script of a fake show with DCA numbers.

As you plot out your DCAs you will want to take your script and sit down and pretend to mix the show and figure out how it will feel to mix. As you do this, it is good to mark the script as you go and build a table that defines each cue. Typically I will have the script and ShowBuilder open to document the DCA scenes. Once I have marked up my script and created this table, I am ready to program the board.

When you program your DCAs there are some good tricks that can be employed. First you want to make it easy and stress-free to recall cues. Unless it is absolutely necessary, you want to place DCA cues in long speeches and if possible do not make them crucial to be fired on an exact moment. This is not always possible, but it keeps the stress level down when you are not panicked about hitting the cue. If you do have to fire a cue in the middle of some quick dialogue it is helpful to have a couple of DCAs carry over from one scene to the next. Let’s say you have two people talking quickly and you need to take a cue to set up for the next people talking. If you have the first two people carry over into the next cue, then you can take the cue any time in their conversation without it being an urgent cue. It can also be a good idea to have people in a cue who aren’t really needed until the next cue; that way, if you throw the cue late you will still have the first couple of people you need.

Both of these tricks allow you to extend the window for when you need to throw a cue. When you use one of these tricks, you can give yourself a visual cue on the board. When you name your DCAs and you have some DCAs that aren’t needed in the cue, a good idea is to label those DCAs in lowercase. Then when you recall the cue that does need those DCAs, you can change the label to using uppercase letters. This will give you a visual cue that you have recalled the cue and you are in the right scene. Also you can add a note in the DCA label for the level of that fader. We do this a lot for the band DCAs or other faders that need to be preset. By putting a –5 under the name, you give yourself guideposts to follow while you mix just by looking at the DCAs.

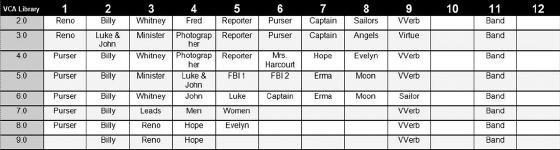

Figure 15.3. The DCA scenes for a show.

To start programming your console you need to understand the rule of the 0 or Unity Gain. If you walk up to almost any board on Broadway, you will find that all the inputs are set to 0 and turned off. That is where we typically start every cue or snapshot. This allows us to assign a VCA and turn the fader on and we are done with that scene. It works on an aesthetic level as well. When you are mixing and look down at your board and everything is a 0 or Unity Gain except for a couple of faders, then you can easily see what the boosts or cuts are. If you are using a board without motorized faders, you want to park the inputs somewhere that is easy to re-establish. If you are using a board with motorized faders, you don’t really want it to have to move faders up and down all night long. Sometimes that is noisy and it will eventually wear out the faders.

It is a good plan to create a cue that is a base point for your show, or a cue that can be recalled to wipe the console back to a neutral state. This typically involves having all the inputs at 0 or Unity Gain. A lot of people call this the base cue and it can take a long time to create. Take your time and create a very accurate base cue. In this cue you will want to name every input and output. You will want to route all of your inputs to Groups and set the Aux mixes. You will also want to do your Mix to Matrix section. We are Matrix obsessed on Broadway. The more Matrix the better. Typically we send our Inputs to Groups and our Groups to the Matrix and the Matrix to the speakers. There are different ways to do the Groups, but the basic idea is to have Groups for the Vocals and Groups for the Band and Groups for the Sound Effects. That allows us to create different mixes quickly to different Matrix, depending on what is needed in that zone. One style of grouping is 1-Men, 2-Women, 3-Band Left, 4-Band Right, 5-Drums Left, 6-Drums Right, 7-SFX Left, 8-SFX Right, 9-Gods. This gives some good options. We can EQ the men and women differently and by breaking the drums out into their own groups we can balance the drums in different locations. Another style of grouping is 1-Head, 2-Ears, 3-Band Left, 4-Band Right, 5-SFX Left, 6-SFX Right, 7-Gods. The Head Group is for any lavs that will be worn on the head. The Ears Group is for any mic that will be worn on the ear. This allows you to quickly find a decent EQ for everyone based on mic position and then individuals can be fine-tuned.

Once you have labeled and assigned everything, you have to develop a strategy for “Recalling.” When you are teching a show, there are times when you want everything to recall and times when you want nothing to recall. All digital boards have the ability to save and recall scenes. Most digital boards have the capability to decide whether you want certain parameters to recall in only some scenes or in all scenes. There are times when you may want an EQ to recall to the stored value and other times when you don’t want it to recall. There are times when you want every aspect of the board to recall and other times when you want only some aspects to recall. Developing your recall strategy is probably the most important part of programming your board. If you do it wrong, you are going to be constantly trying to figure out why you lost settings and the designer is bound to get very frustrated after he finishes quiet time and finds out that you accidentally erased all of his delay settings. There is definitely no right or wrong here. Every console works differently and every designer wants something different. What is important is for the mixer to understand the recall strategy and to make sure nothing accidentally gets lost.

My personal strategy is to start with very little recalling and increase what the board recalls as we move through tech until the show opens and is frozen, and then basically recall everything all the time. When I start, I make sure nothing in the output section recalls. This works for most designers because they don’t really vary the EQ and Delay of the mains that often. There are always exceptions, but it is generally better not to recall the output section at first. The same goes for the band inputs. It is generally a good idea to keep the band inputs static until a basic mix has been found. I usually also safe out the EQ, Compressor, and Gain. The term Safe is used by some digital desks, such as Yamaha. Other desks use different terminology, but the concept is the same. It means to tell a certain parameter not to recall the stored parameter when a scene is recalled. There are typically two types of Safe: Scene Safe and Global Safe. Global Safe means it is Safed in all cues. Scene Safe stores in a scene and tells the parameter whether it is allowed to recall in that cue or not. When I start tech, basically the On/Off and Fader level of my RF inputs recall with every new scene or preset and that is about it. As the system begins to develop, I will start recalling other things. Once we open I will generally recall every scene one at a time and store it. Then I can turn off any Recall Safes and have the board constantly recall everything. If I ever need to make a change during the run, I can easily safe out whatever I need to change.

Once you have your strategy, it is time to program your DCAs. If you have laid the DCA scenes out in a table and marked up your script and built your base cue, this should be very quick and easy. My method is to recall the base cue and then save it as whatever the cue number in the show is going to be. Then I label the DCAs and program the inputs to the DCAs and turn those inputs on. Then I store the cue and recall the base and repeat until I am done. It is very important that you assign a DCA and then turn it on. If you need to take something out of a DCA you turn it off first and then out of the DCA. If you do not follow this order you will open an input up wide, which could cause raging feedback.

As you program this you will find questions you can’t answer, like who will be saying the lines for Sailor 3 and 4. Hopefully the stage manager will give you a breakdown of what ensemble members will be saying or singing certain lines, but if not you should make a list of questions to ask the SM as you program. It is very easy to go back later and assign and turn on the appropriate people. Once you have your DCAs programmed you should be ready for cast onstage. It is not always possible to be completely programmed before the cast starts onstage, but it is a good idea to have as much done as you can. The more you have programmed, the less stress you will have.

No matter what playback system you use, the most important question for the mixer is how it will be triggered. Since the programming will basically be done for you, the only real issue is how you will fire the sound cues. Do you want one button that fires the scene on the board and the sound cues or do you want a separate button, one for sound cues and one for board cues? There is an advantage to both. If you have a separate button for sound cues, then you are less likely to accidentally fire a sound cue. If you use only one button for both, then you simplify the mix, especially if there are lots of sound cues.

It is very common for the design team to program the playback system and the mixer will have very little to do with it. According to union rules the design team is not supposed to touch equipment, but that is a very challenging concept in sound. If you look at the lighting model you can see what we are supposed to be. In lighting there is a lighting programmer. The lighting designer talks to the programmer and explains how he wants something to look and the programmer programs it for him. The LD will tell the programmer to bump up certain lights by a certain percent or change some other parameter, and they will chat with each other on headset constantly.

Could you imagine trying to mix if the sound designer put you on headset and talked to you the whole time asking you to give a 2dB cut at 160 with a Q of 1.2 on Steve? It would be impossible. Or think about how many times you’ve heard the LD say he is cueing ahead or behind. Could you imagine if we were programming ahead and had live mics open of people offstage so we could fix their EQ for an upcoming scene? There is an understanding that what we do is different and requires more hands on from our designers, but the union is entitled to ask the production to hire a “programmer” to deal with this. If you have a programmer on contract, which means a union person is being paid to program the equipment just like in lighting, then people have less of a problem with sound designers touching gear.

The reality of what normally happens though is that the playback system and console are programmed by the designer, mixer, or assistant. It depends on how the designer works. There are shows that have a person dedicated to firing sound cues, which was the case on A Christmas Carol, Fela, and Bombay Dreams when I mixed those shows. More often, all cues are fired by the mixer.