5

Strategy

“We shall either find a way or make one.”

Hannibal

In this chapter

- Competitive position

- Strategy

- Generic strategies

- Strengthening competitive position

- Boosting strategic position

- Strategy in a start-up

- Strategic risks and opportunities

You have already set out the micro-economic backdrop to your business. In Chapter 3 you assessed prospects for market demand and in Chapter 4 for industry competition. Now it’s time to slot your business into that context.

How competitive is your business in each of its main segments? What is your strategy for strengthening competitiveness in key segments? Or boosting the balance of your overall portfolio of segments? What risks may you face and what opportunities can you exploit? That’s for this chapter to consider, and in Chapter 6 we will look at the resources you’ll need to deploy to put that strategy into effect.

And your conclusions in this chapter will form an essential component of the justification of your sales and operating profit forecasts in Chapter 7 of your plan.

One caveat for this chapter of your plan. As for Chapters 3 and 4, this chapter will set out conclusions from the extensive research and analysis you’ll undertake before writing your plan – in this instance on your competitive position and strategy. Very little of the detailed analysis set out below will find its way into your plan. You would lose or bore your backer in no time. Only the conclusions go into the plan. Any further detail can be laid out in Appendix C to your plan on competitive position.

But it will be hugely beneficial if you can convince your backer that your assertions have been pulled not from the top of your head, but from a foundation of solid research and analysis.

Your assertions will have depth, balance and relevance. In so many business plans, the author waxes lyrical on their company’s strengths – for example, how a product has a feature that is unique or by far the best in the market. That may have some truth, but let’s have some perspective. Does the customer perceive a significant difference between your product and that of the closest competitor? Do they care? How important is that feature in an assessment of overall competitive position? Without the rigorous analysis, the reader may remain unconvinced.

In this chapter of your plan, you must not overexaggerate your strong points, nor their importance to the buying decision, nor gloss over your weak points. You must place your firm’s strengths and weaknesses in context – in terms of both the customer’s buying decision and the capabilities of the competition. Imagine if a competitor stumbled across a stray copy of your business plan, left lying on a table at a conference (it does happen). Would they split their sides laughing at the one-sided hyperbole?

Your assertions must be sufficiently robust to withstand the forensic examination of your backer. If they are not, they will pull out, having wasted your time and theirs.

Essential tip

You can always find something nice to say about somebody’s character, appearance and skills, even though in reality you may think that person a rude, scruffy layabout. So too with companies. If you trumpet your firm’s strengths without putting them in context, or acknowledging weaknesses, you invite your backer to be sceptical of your conclusions on your firm’s overall competitive position.

Competitive position

You need to be clear about how your business stacks up against the competition. In each of your main business segments, how well placed are you? And how is that likely to change over the next few years?

To answer that you should ideally go through three stages, for each of your main segments:

- Identify and weight customer purchasing criteria (CPCs) – what customers need from their suppliers in each segment – that is, you and your competitors.

- Identify and weight key success factors (KSFs) – what you and your competitors need to do to satisfy these customer purchasing criteria and run a successful business.

- Assess your competitive position – how you rate against those key success factors relative to your competitors.

Appendix A to this book shows you how to do just that. It shows you how to develop a systematic assessment of where your firm is currently placed relative to your main competitors, and how this is likely to develop over the next few years.

I strongly recommend that you follow the approach of Appendix A. It is comprehensive, rigorous and can be revelatory. It is not, however, necessary for your business plan. Indeed it will not form part of your business plan as delivered to your backer.

It will lie there in the background, forming a solid bedrock of research and analysis to underpin your forecasts in Chapter 7, ready to counter any clever cross-questioning from your backer.

The alternative, a short-cut, is to set out here your firm’s strengths and weaknesses, as recommended in most business plan guides. I have three problems with this approach:

- Setting out strengths and weaknesses without weighting and rating them and deriving a reasoned, balanced conclusion, preferably a weighted average assessment of competitive position, can be misleading.

- This exercise is seldom done for each main business segment, where, virtually by definition of being a different segment, both the weighting and rating, and indeed the overall competitive position, will differ.

- It is too often thrown in as part of a SWOT exercise (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats), which is a dreadful construct. It typically shows just a jumble of items, ungraded for importance, relevance, probability or impact, muddling up business opportunities with market opportunities, business risks with market risks, and coming to no conclusion whatsoever; it is a mess.

But by all means have a go at strengths and weaknesses if you would prefer not to go through the rigour (and, yes, time) of Appendix A. If so, please make sure you are as clear as possible when describing a strength or weakness to your backer by observing these tips:

- Give your backer some impression of the relevance of that factor in assessing a firm’s competitiveness in your main business segment.

- Explain to what extent this is more important in some segments than others.

- Set it out relative to the competition – sure, your customer retention rates are high, but are they higher than those of the market leader? And, if not, what plans do you have to raise them to the best in the business?

- Do not mix opportunities and threats with this assessment of your firm’s strengths and weaknesses – market opportunities and threats have already been discussed in Chapters 3 and 4; business opportunities and threats will be assessed below in the section on strategy and again later in the section on strategic risk.

Once you have set out your firm’s competitive position in its main business segments (following the approach of Appendix A in this book), or taken a short-cut and listed your firm’s strengths and weaknesses (as above), it is time to set out your plans for proactively strengthening your firm’s competitiveness. That is your strategy, and it is covered in the next section.

Essential example

Lonely Planet’s strategy

On my first trip to South-East Asia in the late 1970s, a friend of mine lent me his raggedy copy of a small yellow guidebook, South-East Asia on a Shoestring, of which he said that ‘this’ll be your best mate on the trip’. He wasn’t far wrong.

The market for travel guides must have seemed mature, even crowded, at the start of the 1970s. It was dominated by the Baedeker, Fodor and Michelin guides, differentiated mainly through their red, blue or green jacket covers. There were also Frommer’s Europe on $5 a Day guides for the more budget conscious. More pertinently, there was (and remains to this day) the exceptional (and big) South American Handbook, which combines detailed historical and cultural context with practical advice at all levels of the travel market. But when Tony and Maureen Wheeler travelled ‘in a beat-up old car’ from London to Sydney for their year-long honeymoon in 1973, they found they had little to help them. They had to find where to stay, what to do and how to get there the hard way. And when they arrived in Sydney, ‘flat broke’, they were persuaded to write down their experiences, stapling random pages together at the kitchen table.

Across Asia on the Cheap sold 1,500 copies within a week of its appearance. The Wheelers had tapped into the traveller market, a derivative of the former hippie trail from London to Afghanistan of the late 1960s, but soon to mushroom through the insatiable appetite of young Australians for overland travel – saving up, travelling overland for a year, working in a bar for a year in Earls Court, then taking another slow year to get home – the standard trail. And Lonely Planet was there to help them all along the way.

It did not have it all its own way though. In 1982, Mark Ellingham brought out a Rough Guide to Greece – full of historical and cultural context, along the lines of the South American Handbook, but targeting the traveller market as per Lonely Planet. That developed into a European series and the two soon started to compete head on, especially after Penguin bought Rough Guides in 1995. As with EAT challenging Pret A Manger, as we saw in Chapter 4, both players benefited from tougher competition. Lonely Planet’s strategy had from the outset been one of differentiation – unafraid to take on the giants of Michelin and Fodor, the Wheelers identified a niche market, albeit one poised to grow rapidly, and tailored a product perfectly designed to that niche.

By the 2000s, as the printed product matured, Lonely Planet’s strategy moved into product extension and new media. It developed thematic guides (e.g. on languages, food and walking), brought out its own travel magazine and moved into travel television production. It developed an online travel information and agency service inevitably more comprehensive than the books, threatening cannibalisation. Travellers can now access Lonely Planet information by sitting down in an internet café in La Paz, Lilongwe or Luang Prabang. Yet the books still sell well – travellers, it seems, like to peruse the book as much in the bar or in bed.

Lonely Planet has been an astonishing success story – a veritable labour of love turned into a world-leading business. In 2007 it was bought by BBC Worldwide, turning those one-time hippie trail travellers into deca-millionaires.

Strategy

There are myriad definitions of strategy, ranging from that of General Sun Tzu (‘know your opponent’) in the sixth century BC to that of the rather more recent Kenichi Ohmae (‘in a word, competitive advantage’).

I am an economist, so I believe that we should bring the word ‘resources’ into the definition. Just as economics can be defined as the optimal allocation of a nation’s scarce resources, so I define a company’s strategy thus:

Strategy is how a company deploys its scarce resources to gain a sustainable advantage over the competition.

What your backer needs to know is how you plan to allocate your company’s resources over the business plan period to meet your goals. These resources are essentially your assets – your people, physical assets (for example, buildings, equipment and inventory) and cash (and borrowing capacity). How will you allocate – or invest – these resources to optimal effect?

More precisely, your backer needs to be convinced that your strategy will enhance your firm’s competitive position in key business segments.

You have already set out your firm’s competitive position in the section above. You even had a go at examining how that may change over time.

In this section you must show how you can proactively improve that position through deployment of a winning business strategy. That is how you will provide commercial underpinning to your forecasts in Chapter 7 of your plan. That is how you will convince your backer to back you.

What is your company’s strategy? How will you deploy your scarce resources to gain a sustainable competitive advantage?

First, let’s look at the generic strategies.

Generic strategies

There are again many definitions of generic strategies, with each business guru seeming to come up with their own. But, in essence, and in the vast majority of cases, a company needs to choose between two, very different and easy-to-grasp generic strategies: low-cost or differentiation.

Either strategy can yield a sustainable competitive advantage. Either the company supplies a product that is at lower cost to its competitors or it supplies a product that is sufficiently differentiated from its competitors that customers are prepared to pay a premium price – where the incremental price charged adequately covers the incremental costs of supplying the differentiated product.

For a ready example of a successful low-cost strategy, think of easyJet or Ryanair, where relentless maximisation of load factor enables them to offer seats at scarcely credible prices, compared with those prevailing before they entered the market, and still produce a profit. Or think of IKEA’s stylish but highly price-competitive furniture.

A classic example of the differentiation strategy would be Apple. Never the cheapest, whether in PCs, laptops or mobile phones, but always stylistically distinctive and feature-intensive. Or Pret A Manger in fresh, high-quality fast food.

One variant on these two generic strategies worth highlighting is the focus strategy, developed prominently by Professor Michael Porter. While acknowledging that a firm can typically prosper in its industry by following either a low-cost or differentiation strategy, this alternative is not to address the whole industry but narrow the scope and focus on a slice of it, a single segment. Under these circumstances, a firm can achieve market leadership through focus and exceptional differentiation leading to scale-driven low unit costs.

A classic example of a successful focus strategy would be Honda motorcycles, whose focus on product reliability over decades has yielded the global scale to enable its quality products to remain cost competitive.

Strengthening competitive position

Having clarified which generic strategy underpins your business, how are you planning to improve your competitive position over the plan period? How will you reinforce your competitive advantage?

The answer should lie in the analysis you have already done above when assessing your competitive position versus that of your competitors.

Against which key success factors did you rate less favourably than a key competitor? Is this an important, highly weighted KSF? Will it remain so in the future? Could it become even more important over time? Should you take action to strengthen your performance against this KSF? Should this relative weakness be addressed?

Or should you instead be building on your strengths, widening an already existing gap between you and competitors in a particular KSF? It is inadvisable to generalise, but in theory investment in building on strengths should offer a more favourable risk/reward profile than investing to address weaknesses.

If your generic strategy is one of low cost, what investments or programmes are you planning to reduce costs even further and so stay ahead of the competition? What major investments in plant, equipment, premises, staff, systems, training and/or partnering are you planning? What performance improvement programmes are underway or planned?

If your generic strategy is one of differentiation, what investments or programmes are you planning to reinforce that differentiation and make you stand out even more clearly than your competitors? What major investments in plant, equipment, premises, staff, systems, training, marketing and/or partnering are you planning? What strategic marketing programmes are underway or planned?

If your generic strategy is one of focus, what investments or programmes are you planning to reduce costs and/or reinforce your differentiation? What major investments, performance improvement or strategic marketing programmes are underway or planned?

How will these investments or programmes impact on your competitive position in key business segments? Your backer needs to know.

Essential tip

Whatever your firm’s competitive position in a key business segment today, it probably won’t be the same in three years’ time. Markets evolve, competitors adapt. Your firm needs to take control over its future. Convince your backer that your firm is proactively improving its competitiveness.

Boosting strategic position

So far our analysis has been premised on the strengthening of your competitive position in your key product/market segments over the next few years.

But suppose you don’t have the resources, whether in cash, time or manpower, to do all you would like to do. How should you prioritise between the segments? Which investments or programmes should you do first? Which should be dropped, possibly for ever? Which segments should you get out of?

You may benefit from undertaking a portfolio analysis. This will set out how competitive you are in markets ranked by order of attractiveness. You should invest ideally in segments where you are strongest and/or which are the most attractive. And you should consider withdrawal from segments where you are weaker and/or where your competitive position is not that good.

And finally, should you be looking at entering another business segment (or segments) that is in more attractive markets than the ones you currently address? If so, do you have grounds for believing that you would be at least reasonably placed in this new segment, or that you could readily become reasonably placed?

This analysis will identify your strategic position. This is not to be confused with your competitive position, which relates to how competitive your company is in a particular product/market segment. Your strategic position relates to your balance of competitiveness across all segments, of varying degrees of attractiveness.

First, let’s be clear what we mean by an ‘attractive’ market. The degree of market attractiveness should be measured as a blend of four factors:

- Market size

- Market demand growth

- Competitive intensity

- Market risk.

The larger the market and the faster it is growing, the more attractive, other things being equal, the market is. But be careful with the other two factors, where the converse applies. The greater the competitive intensity in a market and the greater its risk, the less attractive it is.

You will have to use your own judgement on the weighting you apply to each of these factors. Simplest would be to give each of the four an equal weighting, so a rating for overall attractiveness would be the simple average of the ratings for each factor.

You may, however, be risk averse and give a higher importance to the market risk factor. In this case, you would need to derive a weighted average of each of the four ratings.

An example may help. Suppose your company is in four product/market segments and you are contemplating getting into a fifth. You draw up a strategic position chart, where each segment is represented by a circle (see Figure 5.1).

The segment’s position in the chart will reflect both its competitive position (along the x-axis) and its market attractiveness (along the y-axis). The size of each bubble should be roughly proportional to the scale of revenues currently derived from the segment.

The closer your segment is positioned towards the top right-hand corner, the better placed it is. Above the top right dotted diagonal, you should be thinking of investing further in that segment. Should the segment approach the bottom left dotted diagonal, however, you should consider exiting.

figure 5.1 Strategic position: an example

The strategic position shown in Figure 5.1 is sound. It shows favourable strength in the biggest and reasonably attractive segment C, and an excellent position in the somewhat less attractive segment A. Segment D is highly promising and demands more attention, given the currently low level of revenues.

Segment B should perhaps be exited – it’s a rather unattractive segment, and you’re not that well placed. The new segment E seems reasonably promising.

In developing a strategy for this example, you may consider the following worth pursuing:

- Continued development in segments A and C.

- Investment in segment D (see arrow showing the resultant improvement in competitive position).

- Entry to segment E (with competitive position improving over time as market share develops).

- Exit from segment B (see the cross).

How is your strategic position? Hopefully your main segments, from which you derive most revenues, should find themselves positioned above the main diagonal.

Do you have any new segments in mind? How attractive are they? How well placed would you be?

Are there any segments you should be thinking of getting out of?

Which segments are so important that you would derive greatest benefit from improving your competitive position? Where should you concentrate your efforts?

One final word on strategic position. The above example showed the strategic position of a small company involved in five product/market segments.

Exactly the same analysis can and should be undertaken for a larger company involved in, say, five businesses – or strategic business units (SBUs, in management-speak). Each SBU can be plotted against both competitive position (itself a weighted average of that SBU’s competitive position in each of its addressed product/market segments) and market attractiveness (again a weighted average).

And the same conclusions can be drawn. Investment in one SBU, holding another for cash, exiting a third and so on.

If you have plans for improving your strategic position, they should be in your business plan. Your backer needs to know.

Essential example

Reggae Reggae’s strategy

Reggae Reggae Sauce is a classic example of the success of test marketing. For many years, reggae musician Levi Roots and his family set up a stall at the Notting Hill Carnival and sold jerk chicken to passing revellers. He received so many compliments about the sauce, made to his grandmother’s ‘secret recipe’, that he decided to bottle some in his kitchen and sell it separately. For this he received backing of £1,000 from Greater London Enterprise. At the 2006 carnival, these bottles flew off the stall as fast as the jerk chicken.

Encouraged, Roots took his bottles around various trade shows, marketing it innovatively by singing a song about the sauce that he had composed himself. At one such show he was spotted by a BBC producer and a few months later he reprised the song in front of three million viewers on the BBC’s Dragons’ Den. He walked away with an investment of £50,000 for 40% of his company in February 2007, a success attributable partly to his charisma (and song), but mainly, one suspects, to the proven success of the product. It had been test marketed again and again, on the streets, and found to be a winner.

The rest of the story is a phenomenon. The Dragons helped it get on to the shelves at Sainsbury’s, where it was expected to shift 50,000 units a year and ended up selling almost that amount a week. Soon the sauce range was extended, most recently with a Red Hot version, followed by the Reggae Reggae Cookbook, processed foods flavoured with the sauce, Levi Roots branded sandwiches, a Reggae Reggae pizza at Domino’s, a Reggae Reggae drinks range and so on.

One observer (Prabhat Sakya, Yahoo! Finance, 18 April 2011) has valued Roots’ company at £30 million, giving each Dragon a shareholding worth £6 million – a return of 240 times their investment in four years (or an astonishing 194% ROI) – and leaving Roots a very wealthy man. No wonder his latest book is titled You Can Get It If You Really Want.

Strategy in a start-up

The process set out in this chapter is not that different for a start-up, whether serving an existing market or creating a new one. You need to assess your likely competitive position in the main segments where you intend to compete and develop a strategy to enhance that competitiveness over time.

There are three main differences:

- Your competitive position is in the future rather than the present tense.

- It will be affected adversely from the outset by a low rating against all key success factors pertaining to experience.

- Your backer will want to know whether it is defensible once achieved.

Your competitive position in a new venture is a judgement on the future. For an established business, the debate revolves as much around the present and recent past as it does around the future – around the weighting of KSFs and/or your ratings against specific KSFs, as justified by evidence from customer, supplier and other interviews, each of which will be as much based on fact and performance track record as on judgement.

But for a start-up, the debate will be part conjecture, especially if your venture is in a new market. So your arguments must be stronger. And you must find evidence from any possible source.

There is nothing you can do about your new venture’s rating against those KSFs that demand experience. And your rating against market share will be low at the outset; so too perhaps against some cost-related factors, especially those pertaining to scale.

Likewise your rating against some differentiation factors may be low. Your lack of track record may count against you in consistency of product quality, delivery, customer service, sales and marketing, and so on.

In that case, how will your firm compete? It’s not easy being a new entrant to an existing market. Your competitive position will indeed be low relative to the leaders at the outset. However, if you are addressing a growing market and/or you can differentiate your product or service sufficiently, things should improve. Your competitive position in three to five years’ time should have improved measurably – your market share rating should be up, your unit costs down and your service performance improved.

But this analysis further highlights what we discussed in Chapters 2 and 3 about segmentation. If your new venture does not serve an existing market but creates its own, then all changes. The analysis of competition will be undertaken not for the market as a whole but for your addressed product/market segment. And if that is a new segment, created by your new venture, you effectively have no direct competition.

But there are two caveats:

- You will have indirect competition, as discussed in Chapter 4.

- You will in due course face competition from new entrants, if your new market is worthy of pursuit.

This brings us to the third of the main differences between strategy for a start-up and that for an established business: its defensibility.

Remember the definition we used for strategy: ‘Strategy is how a company deploys its scarce resources to gain a sustainable advantage over the competition.’ The all-important word for a start-up in a new market is sustainable.

If your new venture succeeds, you will be targeted. Competitors will eye your newly carved space with envy. They will come after you. And soon.

How will you protect yourself against that competitive response? Your backer needs to know this. If they are a venture capitalist, they will be looking for an exit after five to seven years. Could this be when your competitors have started taking chunks out of your market share? If so, your backer won’t be able to sell out, or only at a discounted price. If there’s a chance of that scenario from the outset, they won’t back you.

There are a number of ways you can try to sustain your competitive advantage:

- Patent protection of key products.

- Sustained innovation, staying one step ahead in product development.

- Sustained process improvement, staying one step ahead in cost competitiveness and efficiency.

- Investment in branding, identifying in the mind of the customer the particular benefit brought by your offering with its name.

- Investment, for business-to-business ventures, in customer relationships.

However you aim to do so, this must form a key component of your business plan. Set out here not only how you are going to achieve a competitive advantage in this newly created market, but also how you will sustain it.

For further reading on strategy in a start-up, or indeed for further thoughts on market demand (see Chapter 3) and competition (Chapter 4) in start-ups, along with more case studies on what worked, what didn’t and why, try John Mullins’ terrific book, The New Business Road Test (3rd edition, FT Prentice Hall, 2010). This is essential reading on all the preparatory work and research you should undertake before drawing up a business plan for a start-up, especially in a new market.

Strategic risks and opportunities

In Chapters 3 and 4 of your plan, you pulled out the main market demand and industry competition risks and opportunities in your line of business. Now you can add those that relate to your competitive position and strategy over the next few years.

In the pages above, you have assessed your competitive position (or prospective position if your venture is a start-up) in key segments. You have set out your strategy for strengthening your position in each key segment, as well as your overall strategic position.

That is what you believe to be the most likely scenario. What are the risks that your competitive positioning could turn out to be worse than that? Suppose, for example, a competitor were to steal a major customer from you? How likely is that? With what sort of impact? What could happen to make your positioning even worse than that?

Conversely, what could happen to improve your competitive prospects significantly? Could a major competitor exit from the market, for example? How likely is that, and with what impact?

What are the big risks – those which are reasonably likely and with reasonable impact (as defined in Chapter 3)? How can they be mitigated? What are the big opportunities? How can you exploit them?

We will return to these big risks and opportunities in Chapter 8.

Essential case study

The Dart Valley Guest House and Oriental Spa business plan, 2011

Chapter 5: Strategy

Dick Jones has found that competition in the three- and four-star hotel/spa business in Devon is of medium to high intensity (see Chapter 4), with the main risk being that the spa goes the way of a fad. But what of Dart Valley’s competitive standing in this market and how might that be improved if they achieve the funding needed for the proposed Phase II development?

Dick is a former management consultant and appreciates that his findings must be rooted in research and analysis, as set out in Appendix A of this book. He rolls up his sleeves. He scans the web, talks to people he knows in the Spa Business Association, reviews notes and literature from the UK Spa & Wellness Conference he attended the previous year and examines the Spa Industry Survey Report for Great Britain & Ireland sponsored by VisitBritain.

He compares this research with his own experience at Dart Valley over the past three years and concludes that the main purchasing criteria for customers of spa services are: the effectiveness of the treatment (the customer must feel that the treatment has done them good); the standard of the premises (preferably clean, hygienic, spacious and with a relaxing ambience); and, of course, price.

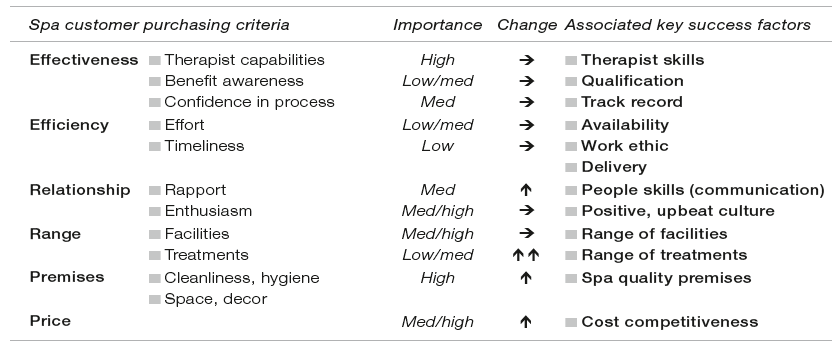

He finds that as customers also consider the range of facilities provided important, from hot tubs to swimming pools, saunas to jacuzzis, and as they become more savvy, they will place greater emphasis on the range of treatments provided – as shown in Table 5.1

He then translates these customer purchasing criteria into key success factors (KSFs) – see Table 5.2. He finds that the winning provider of spa services will have highly skilled and experienced therapists, quality premises, a positive, upbeat culture and tight control of cost.

table 5.1 Customer purchasing criteria from spa services, 2010

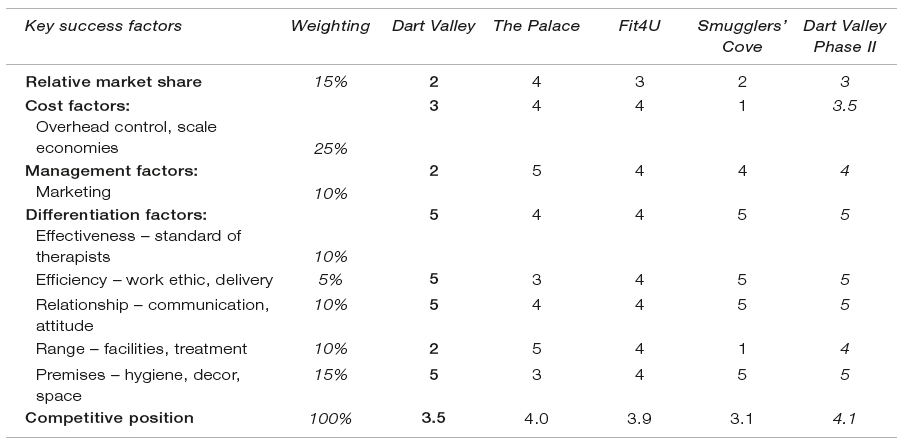

Finally, he allows for the two incremental KSFs of market share and management factors and computes the weighting to each. He is now ready to rate the Dart Valley offering against these KSFs. He is mildly surprised but proud to find that Dart Valley’s overall competitive position in spa services in the South Devon area comes out as favourable to strong, or 3.5 on a scale of 0 to 5 – see Table 5.3 for the Dart Valley results and Appendix A on the methodology for how ratings are calculated.

The Palace, a grand institution in Torquay, with 250 rooms and a full suite of spa, swimming and aquatic facilities, emerges top, of course, but not that much further ahead. Dick believes that his team of therapists is more skilled and more enthusiastic than the team at The Palace, thanks to the personal care taken over their recruitment and motivation by Dick’s wife, Kay. He also believes that the sense of personal space and relaxation, not to mention the extraordinary views, at Dart Valley is in contrast to the slightly cramped and rather overpopulated feel at The Palace’s spa.

table 5.2 Key success factors in spa services, 2010

table 5.3 Dart Valley competitive position in spa services

Not far behind The Palace is the Torquay branch of the national Fit4U chain, a slick operation focusing primarily on its fitness suites and courses, but with an impressive set of spa facilities added on. Good as they are, Dick doesn’t believe they match the standards of excellence and ambience at Dart Valley.

There are a number of other competitors in the Torquay area, but they tend to fall a little behind The Palace and Fit4U, certainly in terms of range of facilities. One other spa offering stands out, however, and that is Smugglers’ Cove, a top-of-the-range boutique hotel perched above its own cove in the South Hams. It claims to offer ‘spa’ facilities, but in reality there’s a treatment room and a sauna and that’s it. But guests are truly pampered there, and one or two of Dart Valley’s excellent therapists also work there, so it ranks as a credible competitor, albeit in its luxury market niche.

Dick knows that little of this analysis, and certainly none of these figures, will find their way into his business plan (we will see later on what will go in). But what the exercise has given him is analysis in depth and thinking in depth, findings rooted in research. And balance.

Dick has shown to himself that Dart Valley is a credible player in the spa services business, with its strong points not overexaggerated and its weak points not glossed over. This must shine through in the plan.

Even more importantly, this analysis has provided a construct for framing the project at the heart of his business plan, the proposed Phase II development of 16 more rooms plus a swimming pool. The final column of Table 5.3 shows clearly that the project could render Dart Valley the leading spa operator in South Devon, thanks to:

- increased market share, hence spread of message

- greater contribution to overheads, hence lower unit costs

- broader range of facilities, not far below that offered by The Palace.

Dick now reproduces the analysis above for Dart Valley’s other two main business segments – accommodation and catering. For purposes of this book, we need not go into similar detail, but suffice it to say that Dick’s conclusions are similarly encouraging.

Dick can now put into words, wrapped up into just three to four pages of A4, what his analysis of competitive position has concluded, namely as follows:

- Dart Valley has come from nowhere to be a credible competitor in its niche

- It has done so, on the one hand, by:

- offering the overnight visitor an experience somewhat out of the ordinary – clean, crisp, comfortable accommodation spiced with a hint of the Orient, with stunning views over the Dart Valley

- offering the diner the choice of traditional British fare or home cooked, delicately spiced oriental cuisine, with the same lovely views

- creating a spacious, relaxing environment, a high quality of therapy and a culture of service and enthusiasm in its spa services – factors that counterbalance the limited range of facilities offered compared to leading local competitors.

- And, on the other, by:

- keeping a tight control over overheads.

- That Dart Valley has become a serious competitor in this industry is evidenced by its occupancy rates, having achieved room occupancy by year three of operations of 71%, well above the average for Torbay hotels of 58% (equivalent to the 43% bedspace occupancy set out in Chapter 4).

- Completion of the two-phase strategy could make Dart Valley the leading provider of spa services in the Torbay and South Hams area, not in terms of scale or market share, but in terms of competitive position, hence profitability.

- Strategic risks are low – Dart Valley will offer in Phase II more of the same successful formula of Phase I and it seems unlikely that this concept, so successful so far, will become dated or of lesser appeal over the next five years.

Dick will proceed to assess the resource implications of this strategy in the next chapter of his plan. Before that, however, he cannot resist comparing what he has written in Chapter 5 with what he would have written four years earlier, when starting up the venture. For Phase I, he had used a mortgage plus the proceeds from the sale of the family home in South-West London as finance – and he had never got round to writing a business plan for himself as the backer (though it might have been a useful exercise).

He finds that much of what he has written in 2010 would have been the same as in 2006. He had researched the spa services market in depth in 2006, so his findings on customer purchasing criteria and key success factors would not have changed much in the interim – only perhaps in the weighting attached to, for example, the range of treatments offered.

The main difference would have been in the use of tense. In 2006 his plan for the new venture would have been in the future tense throughout. The first three bullet points above would have been virtually identical four years earlier, except that they would reflect aspirations for the future, not the factual present.

Thus the first two bullets would have read:

- Dart Valley should be a credible competitor in its niche by 2010.

- It will do so, on the one hand by:

- offering the overnight visitor an experience somewhat out of the ordinary – clean, crisp, accommodation spiced with a hint of the Orient, with stunning views over the Dart Valley – and so on.

Things have worked out pretty much as planned, which gives Dick a feeling of great satisfaction and indeed optimism that Phase II will be worthy of securing a backer.

Essential checklist on strategy

Your chapter on strategy will stand out from nine out of ten other business plans due to its underpinning in research and analysis. Your backer will appreciate this.

Very little of the research you undertook when following Appendix A of this book will find its way directly into this chapter. But it will be there indirectly. This chapter will be just three to four pages long, but it will radiate latent power. The impression will be conveyed to your backer that each statement is rooted in either fact or rigorously supported judgement.

Derive your firm’s competitive position coherently:

- Your understanding of customer purchasing criteria in key business segments – make cursory but pertinent reference to research you have done on this, with further detail as appropriate in Appendix C to your plan.

- Your understanding of key success factors – likewise.

- Your assessment of competitive position – lay out the source of your firm’s competitive advantage in key segments.

Demonstrate how your firm’s strategy will improve performance over the next few years:

- Which of the generic strategies you will deploy.

- What steps will be taken to strengthen competitive position in key segments, by building on strengths and/or working on weaknesses.

- How your firm will boost its strategic position by optimising its portfolio of business segments.

If your business is a new venture in an existing market, set out why you have a sufficiently distinctive angle to survive in the early stages. If you are creating a new product or service, convince the reader that you will find ready buyers, in the right quantities and at the right price.

Finally, alert your backer to the key strategic risks your firm may face and how you intend to mitigate them. And, conversely, highlight the strategic opportunities that may be there for the taking, which will represent upside to your plan’s forecasts.