This section describes, in detail, all CMMI generic goals and generic practices—model components that directly address process institutionalization.

The text of the generic goals and generic practices is not repeated in the process areas. As you address each process area, refer back to this section for details of all generic practices.

Tip

The generic goals and generic practices in the CMMI for Development model are repeated with each process area along with process-area-specific elaborations. This is not the case in CMMI-ACQ. Listing them only in this section means that you will need to refer to this section often for the application of generic goals and generic practices to each process area.

Institutionalization is an important concept in process improvement. When mentioned in the generic goal and generic practice descriptions, institutionalization implies that the process is ingrained in the way the work is performed and there is commitment and consistency to performing the process.

An institutionalized process is more likely to be retained during times of stress. When the requirements and objectives for the process change, however, the implementation of the process may also need to change to ensure that it remains effective. The generic practices describe activities that address these aspects of institutionalization.

Hint

Consider institutionalization mismatches when working process issues that span multiple organizations. An acquirer that has institutionalized a “quantitatively managed” requirements process working with a supplier that has institutionalized a “managed” requirements process may need to pay attention to negotiating measurement definitions across the team.

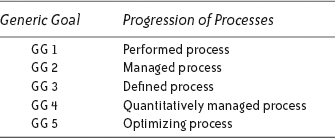

The degree of institutionalization is embodied in the generic goals and in the names of the processes that correspond to each goal as indicated in Table 8.1.

The progression of process institutionalization is characterized in the following descriptions of each process.

A performed process is a process that accomplishes the work necessary to produce work products. The specific goals of the process area are satisfied.

A managed process is a performed process that is planned and executed in accordance with policy; employs skilled people who have adequate resources to produce controlled outputs; involves relevant stakeholders; is monitored, controlled, and reviewed; and is evaluated for adherence to its process description. The process may be used by a project, group, or organizational function. Management of the process focuses on achieving the objectives established for the process, such as cost, schedule, and quality. The control provided by a managed process ensures that the established process is retained during times of stress.

The organization establishes requirements and objectives for the process. The status of the work products and delivery of the services are visible to management at defined points (e.g., at major milestones and completion of major tasks). Commitments are established among those performing the work and the relevant stakeholders and these commitments are revised as necessary. Work products are reviewed with relevant stakeholders and are controlled. The work products and services satisfy their specified requirements.

A critical distinction between a performed process and a managed process is the extent to which the process is managed. A managed process is planned (the plan may be part of a more encompassing plan) and the performance of the process is managed against the plan. Corrective actions are taken when the actual results deviate significantly from the plan. A managed process achieves the objectives of the plan and is institutionalized for consistent performance.

A defined process is a managed process that is tailored from the organization’s set of standard processes according to the organization’s tailoring guidelines; has a maintained process description; and contributes work products, measures, and other process improvement information to the organizational process assets.

The organizational process assets are artifacts that relate to describing, implementing, and improving processes. These artifacts are assets because they are developed or acquired to meet the business objectives of the organization, and they represent investments by the organization that are expected to provide current and future business value.

The organization’s set of standard processes, which are the basis of the defined process, are established and improved over time. Standard processes describe fundamental process elements that are expected in defined processes. Standard processes also describe relationships (e.g., the ordering and the interfaces) among these process elements. The organization-level infrastructure to support current and future use of the organization’s set of standard processes is established and improved over time. (See the definition of “standard process” in the glossary.)

A project’s defined process provides a basis for planning, performing, and improving the project’s tasks and activities. A project may have more than one defined process (e.g., one for developing the product and another for testing the product).

A defined process clearly states the following:

• Purpose

• Inputs

• Entry criteria

• Activities

• Roles

• Measures

• Verification steps

• Outputs

• Exit criteria

A critical distinction between a managed process and a defined process is the scope of application of the process descriptions, standards, and procedures. For a managed process, the process descriptions, standards, and procedures are applicable to a particular project, group, or organizational function. As a result, the managed processes of two projects in one organization may be different.

Another critical distinction is that a defined process is described in more detail and is performed more rigorously than a managed process. This means that improvement information is easier to understand, analyze, and use. Finally, management of the defined process is based on the additional insight provided by an understanding of the interrelationships of the process activities and detailed measures of the process, its work products, and its services.

A quantitatively managed process is a defined process that is controlled using statistical and other quantitative techniques. The product quality, service quality, and process-performance attributes are measurable and controlled throughout the project.

Quantitative objectives are established based on the capability of the organization’s set of standard processes; the organization’s business objectives; and the needs of the customer, end users, organization, and process implementers, subject to the availability of resources. The people performing the process are directly involved in quantitatively managing the process.

Quantitative management is performed on the overall set of processes that produces a product. The subprocesses that significantly contribute to overall process performance are statistically managed. For these selected subprocesses, detailed measures of process performance are collected and statistically analyzed. Special causes of process variation are identified and, as appropriate, the source of the special cause is addressed to prevent its recurrence.

Quality and process-performance measures are incorporated into the organization’s measurement repository to support future fact-based decision making.

Activities for quantitatively managing the performance of a process include the following:

• Identifying subprocesses to be brought under statistical management

• Identifying and measuring product and process attributes important to quality and process performance

• Identifying and addressing special causes of subprocess variation (based on the selected product and process attributes and subprocesses selected for statistical management)

• Managing each selected subprocess to bring its performance within natural bounds (i.e., making the subprocess performance statistically stable and predictable based on the selected product and process attributes)

• Predicting the ability of the process to satisfy established quantitative quality and process-performance objectives

• Taking appropriate corrective actions when the established quantitative quality and process-performance objectives will not be satisfied

Corrective actions include updating the objectives or ensuring that relevant stakeholders have a quantitative understanding of, and have agreed to, the performance shortfall.

A critical distinction between a defined process and a quantitatively managed process is the predictability of process performance. The term quantitatively managed implies using appropriate statistical and other quantitative techniques to manage the performance of one or more critical subprocesses so that the performance of the process can be predicted. A defined process provides only qualitative predictability.

An optimizing process is a quantitatively managed process that is adapted to meet current and projected business objectives. An optimizing process focuses on continually improving process performance through both incremental and innovative technological improvements. Process improvements that address common causes of process variation, root causes of defects, and other problems; and those that would measurably improve the organization’s processes are identified, evaluated, and deployed, as appropriate. Improvements are selected based on a quantitative understanding of their expected contribution to achieving the organization’s process improvement objectives versus the cost and impact to the organization.

Selected incremental and innovative technological process improvements are systematically managed and deployed into the organization. The effects of the deployed process improvements are measured and compared to quantitative process improvement objectives.

In an optimizing process, common causes of process variation are investigated to determine how to shift the mean or decrease the variation in quality and process performance. Changes that support the achievement of the organization’s process improvement objectives are candidates for deployment.

A critical distinction between a quantitatively managed process and an optimizing process is that the optimizing process is continuously improved by addressing common causes of process variation. A quantitatively managed process is concerned with addressing special causes of process variation and providing statistical predictability of results. Although the process may produce predictable results, the results may be insufficient to achieve the organization’s process improvement objectives.

Generic goals evolve so that each goal provides a foundation for the next. Therefore, the following conclusions can be made.

• A managed process is a performed process.

• A defined process is a managed process.

• A quantitatively managed process is a defined process.

• An optimizing process is a quantitatively managed process.

Thus, applied sequentially and in order, the generic goals describe a process that is increasingly institutionalized from a performed process to an optimizing process.

Achieving GG 1 for a process area is equivalent to satisfying the specific goals of the process area.

Achieving GG 2 for a process area is equivalent to managing the performance of processes associated with the process area. There is a policy that indicates you will perform it. There is a plan for performing it. Resources are provided, responsibilities are assigned, training on how to perform it is available, selected work products from performing the process are controlled, and so on. In other words, the process is planned and monitored just like any project or support activity.

Achieving GG 3 for a process area assumes that an organizational standard process exists that can be tailored to create the process you will use. Tailoring might result in making no changes to the standard process. In other words, the process used and the standard process may be identical. Using the standard process “as is” is tailoring because the choice is made that no modification is required.

Each process area describes multiple activities, some of which are repeatedly performed. You may need to tailor the way one of these activities is performed to account for new capabilities or circumstances. For example, you may have a standard for developing or obtaining organizational training that does not consider Web-based training. When preparing to develop or obtain a Web-based course, you may need to tailor the standard process to account for the challenges and benefits of Web-based training.

Achieving GG 4 or GG 5 for a process area is conceptually feasible but may not be economical except, perhaps, in situations in which the product domain is stable for an extended period or in situations in which the process area or domain is a critical business driver.

This section describes all of the generic goals and generic practices as well as their subpractices, notes, examples, and references. The generic goals are organized in numerical order, GG 1 through GG 5. The generic practices are also organized in numerical order under the generic goal they support.

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the text of the generic practices is not repeated in the process areas; the text for each generic goal and generic practice is found only here.

The process supports and enables achievement of the specific goals of the process area by transforming identifiable input work products to produce identifiable output work products.

Perform the specific practices of the process area to develop work products and provide services to achieve the specific goals of the process area.

The purpose of this generic practice is to produce the work products and deliver the services that are expected by performing the process. These practices may be done informally, without following a documented process description or plan. The rigor with which these practices are performed depends on the individuals managing and performing the work and may vary considerably.

The process is institutionalized as a managed process.

Establish and maintain an organizational policy for planning and performing the process.

The purpose of this generic practice is to define the organizational expectations for the process and make these expectations visible to those in the organization who are affected. In general, senior management is responsible for establishing and communicating guiding principles, direction, and expectations for the organization.

Tip

Policy direction may come from multiple levels above the project. For example, in the DoD, policy is established by legislation, the Pentagon, senior acquisition executives, product center management, and others.

Not all direction from senior management will bear the label policy. The existence of appropriate organizational direction is the expectation of this generic practice, regardless of what it is called or how it is imparted.

This policy establishes organizational expectations for planning and performing the process, including not only the elements of the process addressed directly by the acquirer, but also the interactions of the acquirer with suppliers.

Establish and maintain the plan for performing the process.

The purpose of this generic practice is to determine what is needed to perform the process and achieve the established objectives, to prepare a plan for performing the process, to prepare a process description, and to get agreement on the plan from relevant stakeholders.

The practical implications of applying a generic practice vary for each process area.

Therefore, this generic practice may either reinforce expectations set elsewhere in CMMI or set new expectations that should be addressed.

Refer to the Project Planning process area for more information about establishing and maintaining a project plan.

Establishing a plan includes documenting both the plan and the process. Maintaining the plan includes updating it to reflect corrective actions or changes in requirements or objectives.

Hint

This practice does not require a separate plan for each process area. Consider incorporating process area planning requirements into existing project plans (e.g., systems engineering plan or program management plan).

- Define and document the plan for performing the process.

This plan may be a stand-alone document, a plan embedded in a more comprehensive document, or a plan distributed across multiple documents. In the case of a plan being distributed across multiple documents, ensure that a coherent picture of who does what is preserved. Documents may be hardcopy or softcopy.

- Define and document the process description.

The process description, which includes relevant standards and procedures, may be included as part of the plan for performing the process or may be referenced in the plan.

- Review the plan with relevant stakeholders and get their agreement.

This review includes ensuring that the planned process satisfies the applicable policies, plans, requirements, and standards to provide assurance to relevant stakeholders.

- Revise the plan as necessary.

Provide adequate resources for performing the process, developing the work products, and providing the services of the process.

The purpose of this generic practice is to ensure that resources necessary to perform the process as defined by the plan are available when they are needed. Resources include adequate funding, appropriate physical facilities, skilled people, and appropriate tools.

The interpretation of the term adequate depends on many factors and can change over time. Inadequate resources may be addressed by increasing resources or by removing requirements, constraints, and commitments.

Hint

In addition to a skilled staff, consider other resource needs of the project team and suppliers throughout the lifecycle. Examples include collaboration environments for “system of systems” acquisition, tools for engineering analysis and decision making, test beds or simulators, access to operational data or environments, benchmark data, and access to targeted “experts” in areas of high risk.

Assign responsibility and authority for performing the process, developing the work products, and providing the services of the process.

The purpose of this generic practice is to ensure there is accountability for performing the process and achieving the specified results throughout the life of the process. The people assigned must have the appropriate authority to perform their assigned responsibilities.

Responsibility can be assigned using detailed job descriptions or in living documents, such as the plan for performing the process. Dynamic assignment of responsibility is another legitimate way to perform this generic practice, as long as the assignment and acceptance of responsibility are ensured throughout the life of the process.

- Assign overall responsibility and authority for performing the process.

- Assign responsibility and authority for performing the tasks of the process.

- Confirm that the people assigned to the responsibilities and authorities understand and accept them.

Train the people performing or supporting the process as needed.

Hint

Consider sharing training opportunities for project-specific needs across the acquirer, supplier, and end-user teams.

The purpose of this generic practice is to ensure that the people have the necessary skills and expertise to perform or support the process.

Appropriate training is provided to the people who will be performing the work. Overview training is provided to orient people who interact with those performing the work.

Training supports the successful performance of the process by establishing a common understanding of the process and by imparting the skills and knowledge needed to perform the process.

Experience (e.g., participation in a project with responsibility for managing some acquisition processes) may be substituted for training.

The acquisition organization should conduct a training needs analysis to understand its process training needs at both the organization and project levels. Then, appropriate training vehicles can be identified and provided to minimize process-performance-related risks.

Refer to the Organizational Training process area for more information about training the people performing or supporting the process.

Place designated work products of the process under appropriate levels of control.

The purpose of this generic practice is to establish and maintain the integrity of designated work products of the process (or their descriptions) throughout their useful life.

Designated work products are identified in the plan for performing the process, along with a specification of the appropriate level of control.

Different levels of control are appropriate for different work products and for different points in time. For some work products, it may be sufficient to maintain version control (i.e., the version of the work product in use at a given time, past or present, is known and changes are incorporated in a controlled manner). Version control is usually under the sole control of the work product owner (which may be an individual, a group, or a team).

Sometimes it may be critical that work products be placed under formal or baseline configuration management. This type of control includes defining and establishing baselines at predetermined points. These baselines are formally reviewed and agreed on and serve as the basis for further development of designated work products.

Refer to the Configuration Management process area for more information about placing work products under configuration management.

Additional levels of control between version control and formal configuration management are possible. An identified work product may be under different levels of control at different points in time.

Hint

Pay special attention to the configuration management of program documentation and products when moving from one phase of the program to another, especially if there is a hand-off of system development or maintenance responsibility from supplier to supplier or to an internal maintenance group.

The acquirer is responsible for establishing and maintaining baselines and ensuring designated acquirer work products and supplier deliverables are placed under appropriate levels of control.

Identify and involve the relevant stakeholders of the process as planned.

The purpose of this generic practice is to establish and maintain the expected involvement of stakeholders during the execution of the process.

Refer to the Project Planning process area for more information about planning for stakeholder involvement.

To plan stakeholder involvement, ensure that sufficient stakeholder interaction necessary to accomplish the process occurs, while avoiding excessive numbers of stakeholders that could impede process execution.

Hint

Use surrogates when the relevant stakeholder group is too large. For example, stakeholders for review and acceptance of an environmental impact statement may include the entire population of a given area, so a representative subgroup may be needed to make involving them practical.

Subpractices

- Identify stakeholders that are relevant to the process and plan their appropriate involvement.

Relevant stakeholders are identified among suppliers of inputs to, users of outputs from, and performers of activities within the process. Once relevant stakeholders are identified, the appropriate level of their involvement in process activities is planned.

- Share these identifications with project planners or other planners, as appropriate.

- Involve relevant stakeholders as planned.

Monitor and control the process against the plan for performing the process and take appropriate corrective action.

The purpose of this generic practice is to perform the direct day-to-day monitoring and controlling of the process. Appropriate visibility into the process is maintained so that appropriate corrective action can be taken when necessary. Monitoring and controlling the process involves measuring appropriate attributes of the process or work products produced by the process.

Hint

Use this practice to determine the effectiveness of your processes. A SCAMPI appraisal team may not be able to assess process effectiveness, but it will check to see whether you can judge adequacy and are making adjustments accordingly.

Refer to the Project Monitoring and Control process area for more information about monitoring and controlling the project and taking corrective action.

Refer to the Measurement and Analysis process area for more information about measurement.

The project collects and analyzes measurements from the acquirer and from the supplier to effectively monitor and control the project.

Subpractices

- Measure actual performance against the plan for performing the process.

Measurements are collected from the process, its work products, and its services.

- Review accomplishments and results of the process against the plan for performing the process.

- Review activities, status, and results of the process with the immediate level of management responsible for the process and identify issues. Reviews are intended to provide the immediate level of management with appropriate visibility into the process. The reviews can be both periodic and event-driven.

- Identify and evaluate effects of significant deviations from the plan for performing the process.

- Identify problems in the plan for performing the process and in the execution of the process.

- Take corrective action when requirements and objectives are not being satisfied, when issues are identified, or when progress differs significantly from the plan for performing the process.

There are inherent risks that should be considered before corrective action is taken.

- Track corrective action to closure.

Objectively evaluate adherence of the process against its process description, standards, and procedures, and address noncompliance.

The purpose of this generic practice is to provide credible assurance that the process is implemented as planned and adheres to its process description, standards, and procedures. This generic practice is implemented, in part, by evaluating selected work products of the process. (See the definition of “objectively evaluate” in the glossary.)

Refer to the Process and Product Quality Assurance process area for more information about objectively evaluating adherence.

People not directly responsible for managing or performing the activities of the process typically evaluate adherence. In many cases, adherence is evaluated by people in the organization but external to the process or project or by people external to the organization. As a result, credible assurance of adherence can be provided even in times when the process is under stress (e.g., when the effort is behind schedule or over budget).

Review the activities, status, and results of the process with higher-level management and resolve issues.

The purpose of this generic practice is to provide higher-level management with appropriate visibility into the process.

Hint

Some acquisition projects have multiple reporting paths. Make explicit who is considered “higher-level management.”

Higher-level management includes those levels of management in the organization above the immediate level of management responsible for the process. In particular, higher-level management includes senior management. These reviews are for managers who provide the policy and overall guidance for the process and not for those who perform the direct day-to-day monitoring and controlling of the process.

Hint

Not every process area will be included in each review with senior management. Establish a strategic rhythm for reviews that includes examination of high-risk areas as well as regular health checks on process execution.

Different managers have different needs for information about the process. These reviews help ensure that informed decisions on the planning and performing of the process can be made. Therefore, these reviews are both periodic and event-driven.

Proposed changes to commitments to be made external to the organization (e.g., changes to supplier agreements) are typically reviewed with higher-level management to obtain their concurrence with the proposed changes.

The process is institutionalized as a defined process.

Establish and maintain the description of a defined process.

The purpose of this generic practice is to establish and maintain a description of the process that is tailored from the organization’s set of standard processes to address the needs of a specific situation. The organization should have standard processes that cover the process area and have guidelines for tailoring these standard processes to meet the needs of a project or organizational function. With a defined process, variability in how the processes are performed across the organization is reduced and process assets, data, and learning can be effectively shared.

Hint

Don’t go overboard. Use lightweight descriptions that are usable by project team members. Incorporate these descriptions (directly or by reference) into program plans (e.g., systems engineering plan and program management plan).

Refer to the Organizational Process Definition process area for more information about the organization’s set of standard processes and tailoring guidelines.

Refer to the Integrated Project Management process area for more information about establishing and maintaining the project’s defined process.

The descriptions of defined processes provide the basis for planning, performing, and managing activities, work products, and services associated with the process.

Subpractices

- Select from the organization’s set of standard processes those processes that best meet the needs of the project or organizational function.

- Establish the defined process by tailoring the selected processes according to the organization’s tailoring guidelines.

- Ensure that the organization’s process objectives are appropriately addressed in the defined process.

- Document the defined process and records of tailoring.

- Revise the description of the defined process as necessary.

Collect work products, measures, measurement results, and improvement information derived from planning and performing the process to support the future use and improvement of the organization’s processes and process assets.

The purpose of this generic practice is to collect information and artifacts derived from planning and performing the process. This generic practice is performed so that information and artifacts can be included in organizational process assets and made available to those who are (or who will be) planning and performing the same or similar processes. The information and artifacts are stored in the organization’s measurement repository and the organization’s process asset library.

Hint

Periodically review whether the information provided to the organization is still relevant and useful and adjust your collection practices as needed. Often, metrics used and measurements gathered will change as the organization’s proficiency in quantitative management increases.

Refer to the Organizational Process Definition process area for more information about incorporating the work products, measures, measurement results, and improvement information into the organization’s measurement repository and process asset library.

Refer to the Integrated Project Management process area for more information about contributing work products, measures, measurement results, and documented experiences to organizational process assets.

Subpractices

- Store process and product measures and measurement results in the organization’s measurement repository.

The process and product measures are primarily those defined in the common set of measures for the organization’s set of standard processes.

- Submit documentation for inclusion in the organization’s process asset library.

- Document lessons learned from the process for inclusion in the organization’s process asset library.

- Propose improvements to organizational process assets.

The process is institutionalized as a quantitatively managed process.

Establish and maintain quantitative objectives for the process, which address quality and process performance, based on customer needs and business objectives.

The purpose of this generic practice is to determine and obtain agreement from relevant stakeholders about quantitative objectives for the process. These quantitative objectives can be expressed in terms of product quality, service quality, and process performance.

Refer to the Quantitative Project Management process area for more information about establishing quantitative objectives for subprocesses of the project’s defined process.

These quantitative objectives may be specific to the process or they may be defined for a broader scope (e.g., for a set of processes). In the latter case, these quantitative objectives may be allocated to some of the included processes.

These quantitative objectives are criteria used to judge whether the products, services, and process performance will satisfy the customers, end users, organization management, and process implementers. These quantitative objectives go beyond the traditional end-product objectives. They also cover intermediate objectives used to manage the achievement of the objectives over time. They reflect, in part, the demonstrated performance of the organization’s set of standard processes. These quantitative objectives should be set to values that are likely to be achieved when the processes or subprocesses involved are stable and within their natural bounds.

Hint

When establishing quantitative objectives for a process, understanding the “voice of the process” helps you understand how likely you are to satisfy the “voice of the customer.”

Subpractices

- Establish quantitative objectives that pertain to the process.

- Allocate quantitative objectives to the process or its subprocesses.

Stabilize the performance of one or more subprocesses to determine the ability of the process to achieve the established quantitative quality and process-performance objectives.

The purpose of this generic practice is to stabilize the performance of one or more subprocesses of the defined process, which are critical contributors to overall performance, using appropriate statistical and other quantitative techniques. Stabilizing selected subprocesses supports predicting the ability of the process to achieve the established quantitative quality and process-performance objectives.

Refer to the Quantitative Project Management process area for more information about selecting subprocesses for statistical management, monitoring the performance of subprocesses, and other aspects of stabilizing subprocess performance.

A stable subprocess shows no significant indication of special causes of process variation. Stable subprocesses are predictable within the limits established by natural bounds of the subprocess. Variations in the stable subprocess are changes due to a common cause system.

Predicting the ability of the process to achieve the established quantitative objectives requires a quantitative understanding of the contributions of the subprocesses that are critical to achieving these objectives and establishing and managing against interim quantitative objectives over time.

Selected process and product measures and measurement results are incorporated into the organization’s measurement repository to support process-performance analysis and future fact-based decision making.

Hint

Consult statistical process control experts who are familiar with CMMI when selecting subprocesses to statistically manage.

Subpractices

- Statistically manage the performance of one or more subprocesses that are critical contributors to the overall performance of the process.

- Predict the ability of the process to achieve its established quantitative objectives considering the performance of the statistically managed subprocesses.

- Incorporate selected process-performance measurement results into the organization’s process-performance baselines.

The process is institutionalized as an optimizing process.

Ensure continuous improvement of the process in fulfilling the relevant business objectives of the organization.

The purpose of this generic practice is to select and systematically deploy process and technology improvements that contribute to meeting established quality and process-performance objectives.

Refer to the Organizational Innovation and Deployment process area for more information about selecting and deploying incremental and innovative improvements that measurably improve the organization’s processes and technologies.

Optimizing processes to be agile and innovative depends on the participation of an empowered work force aligned with the organization’s business values and objectives. The organization’s ability to rapidly respond to changes and opportunities is enhanced by finding ways to accelerate and share learning. Improvement of the processes is inherently part of everyone’s role, resulting in a cycle of continual improvement.

Subpractices

- Establish and maintain quantitative process improvement objectives that support the organization’s business objectives.

The quantitative process improvement objectives may be specific to an individual process or they may be defined for a broader scope (i.e., for a set of processes), with individual processes contributing to achieving these objectives. Objectives that are specific to an individual process are typically allocated from quantitative objectives established for a broader scope.

These process improvement objectives are primarily derived from the organization’s business objectives and from a detailed understanding of process capability. These objectives are the criteria used to judge whether process performance is quantitatively improving the organization’s ability to meet its business objectives. These process improvement objectives are often set to values beyond current process performance, and both incremental and innovative technological improvements may be needed to achieve these objectives. These objectives may also be revised frequently to continue to drive the improvement of the process (i.e., when an objective is achieved, it may be set to a new value that is again beyond the new process performance). These process improvement objectives may be the same as, or a refinement of, objectives established in the Establish Quantitative Objectives for the Process generic practice, as long as they can serve as both drivers and criteria for successful process improvement.

Hint

At capability level 4, you establish quantitative objectives based on the “voice of the process” and the “voice of the customer” (e.g., fewer than 3.6 defects per engineering change proposal). At capability level 5, you establish quantitative improvement objectives (e.g., decrease engineering change proposal defects by 50 percent).

- Identify process improvements that will likely result in measurable improvements to process performance.

Process improvements include both incremental changes and innovative technological improvements. Innovative technological improvements are typically pursued as efforts that are separately planned, performed, and managed. Piloting is often performed. These efforts often target process factors that a process-performance analysis has determined to be key to significant measurable improvement.

- Define strategies and manage the deployment of selected process improvements based on quantified expected benefits, estimated costs and impacts, and measured change to process performance.

The costs and benefits of these improvements are estimated quantitatively, and actual costs and benefits are measured. Benefits are primarily considered relative to the organization’s quantitative process improvement objectives. Improvements are made to both the organization’s set of standard processes and defined processes.

Managing the deployment of process improvements includes piloting changes and implementing adjustments as appropriate, addressing potential and real barriers to deployment, minimizing disruption to ongoing efforts, and managing risks.

Identify and correct the root causes of defects and other problems in the process.

The purpose of this generic practice is to analyze defects and other problems encountered in a quantitatively managed process, to correct the root causes of these types of defects and problems, and to prevent these defects and problems from occurring in the future.

X-Ref

Although an Ishikawa diagram (i.e., fishbone diagram) is a common tool for simple root cause analysis, most defects or problems require more in-depth analysis. Consider tools such as the Current Reality Tree from the Theory of Constraints. For more information, visit the Goldratt Institute at www.goldratt.com/.

Refer to the Causal Analysis and Resolution process area for more information about identifying and correcting root causes of selected defects. Even though the Causal Analysis and Resolution process area has a project context, it can be applied to processes in other contexts as well.

Root cause analysis can be applied beneficially to processes that are not quantitatively managed. However, the focus of this generic practice is to act on a quantitatively managed process, though the final root causes may be found outside of that process.

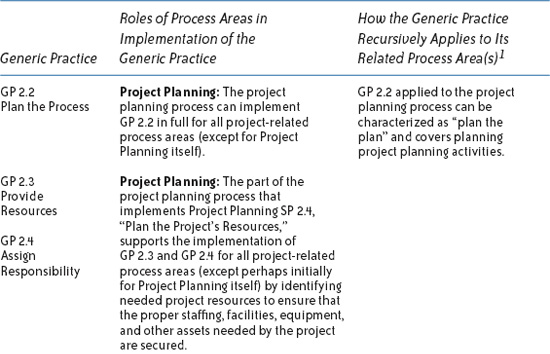

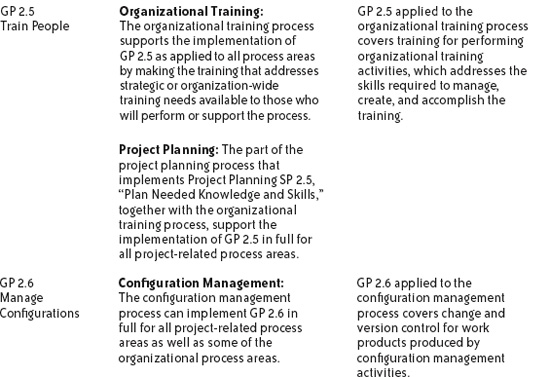

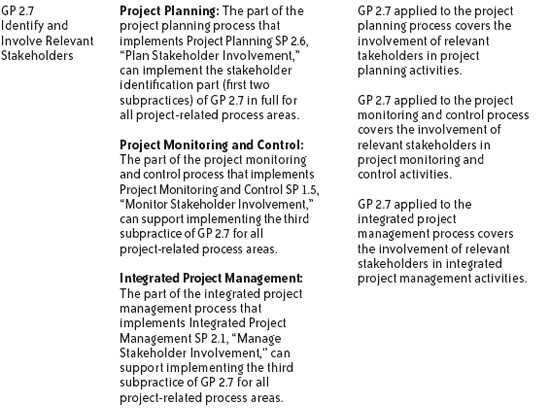

This section helps you to better understand the generic practices and provides information to help you interpret and apply generic practices in your organization.

Generic practices are model components applicable to all process areas. Think of generic practices as reminders. They remind you to do things right, and they are expected model components.

For example, when you are achieving the specific goals of the Project Planning process area, you are establishing and maintaining a plan that defines project activities. One of the generic practices that applies to the Project Planning process area is “Establish and maintain the plan for performing the process” (GP 2.2). When applied to this process area, this generic practice reminds you to plan the activities involved in creating the plan for the project.

When you are satisfying the specific goals of the Organizational Training process area, you are developing the skills and knowledge of people in your project and organization so that they can perform their roles effectively and efficiently. When applying the same generic practice (GP 2.2) to the Organizational Training process area, this generic practice reminds you to plan the activities involved in developing the skills and knowledge of people in the organization.

Although generic goals and generic practices are the model components that directly address the institutionalization of a process across the organization, many process areas likewise address institutionalization by supporting the implementation of generic practices. Knowing these relationships will help you effectively implement generic practices.

Such process areas contain one or more specific practices that, when implemented, may also fully implement a generic practice or generate a work product that is used in the implementation of a generic practice.

An example is the Configuration Management process area and GP 2.6, “Place designated work products of the process under appropriate levels of control.” To implement the generic practice for one or more process areas, you might choose to implement the Configuration Management process area, in full or in part, to implement the generic practice.

Another example is the Organizational Process Definition process area and GP 3.1, “Establish and maintain the description of a defined process.” To implement this generic practice for one or more process areas, you should first implement the Organizational Process Definition process area, in full or in part, to establish the organizational process assets that are needed to implement the generic practice.

Table 8.2 describes (1) the process areas that support the implementation of generic practices and (2) the recursive relationships between generic practices and their closely related process areas. Both types of relationships are important to remember during process improvement to take advantage of the natural synergies that exist between the generic practices and their related process areas.

Given the dependencies that generic practices have on these process areas, and given the more holistic view that many of these process areas provide, these process areas are often implemented early, in whole or in part, before or concurrent with implementing the associated generic practices.

There are also a few situations in which the result of applying a generic practice to a particular process area would seem to make a whole process area redundant, but in fact, it does not. It may be natural to think that applying GP 3.1, “Establish a Defined Process,” to the Project Planning and Project Monitoring and Control process areas yields the same effect as the first specific goal of Integrated Project Management, “Use the Project’s Defined Process.”

Although it is true that there is some overlap, the application of the generic practice to these two process areas provides defined processes covering project planning and project monitoring and control activities. These defined processes do not necessarily cover support activities (such as configuration management), other project management processes (such as integrated project management), or the acquisition processes. In contrast, the project’s defined process, provided by the Integrated Project Management process area, covers all appropriate processes.