27. Case Study: A Joint Computer Center Organization: Triangle Universities Computation Center

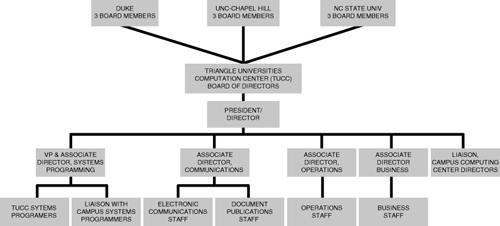

Triangle Universities Computation Center (TUCC) organization chart as of 1980

The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers.

RICHARD W. HAMMING [1962], NUMERICAL

METHODS FOR SCIENTISTS AND ENGINEERS

Highlights and Peculiarities

Bold Decision

Establish this as a joint center. Three universities would pool their resources, co-own, and operate a single high-performance computation center.

Pooling Resources

To exploit the quadratic performance/price curve, resources would be pooled. At the time, and for many years, spending n times as much typically bought at least n2 times as much computing capability. This fact provided a strong economic incentive to overcome the real and foreseen difficulties in co-owning a center.

No Organizational Models

The concept of a joint academic computation center was unexplored, so far as we knew, so there were no models for the organization.

Decision-Making Power

The budgeted commodity in the design was power. How to protect individual owners’ distinct interests, while enabling efficient decision making?

Diverse Applications

Some of the owners used the center for both academic and administrative computing; others, for academic computing only.

Neutral Site

A building was acquired in the Research Triangle Park, about equidistant from each campus.

Telecomputing Crucial but Not Sufficient

The IBM System/360 equipment acquired was designed and software-supported for remote job entry and interactive computing. It was initially used in remote-job-entry mode, but with a priority system that emphasized quick turnaround for small jobs. A courier service hauled tapes and disk packs back and forth in a station wagon to provide “high-bandwidth” transmission of large datasets.

Statewide Influence

In 1964, few higher-education institutions in North Carolina (other than the TUCC owners) had any computing capability or know-how. A separate organization, the North Carolina Computer Orientation Project under the North Carolina Board of Higher Education, rented TUCC capacity and offered other North Carolina universities and colleges

• A year of free computer time at 100 jobs per month

• A year’s free use of a teletype machine installed on their campus

• The free services of “circuit riders” who introduced computing by visiting campuses, teaching teachers, holding workshops, providing telephonic consultation, and troubleshooting

Some 100 institutions took advantage of this service, many continuing their TUCC use at their own expense for years.

Durability

The TUCC organization proved effective for 18 years, even as the relative needs of the three co-owners diverged. It was made obsolete by the minicomputer revolution, although the institutions operated a joint supercomputer center specialized for scientific applications for many years thereafter, under a different organizational model.

Introduction and Context

Location:

Research Triangle Park, NC

Owners:

Duke University, a private university (Durham, NC)

North Carolina State University (Raleigh, NC)

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Organization Designers:

TUCC Board of Directors

Dates:

1964–1992

Context

Duke University, North Carolina State University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill each had first-generation computers, operated by centralized computer centers. Each needed to upgrade in capacity and capability. Each wanted more computer than it could afford.

The three universities decided to pool their resources and operate a single modern high-performance facility (more than they could collectively afford without help).

The National Science Foundation made a substantial grant, partly to fund exploration of the novel organizational model for providing academic computing service for research.

IBM, having located a new product development and manufacturing facility in Research Triangle Park, helped quite substantially with funding for the first three years, by renting a night shift.

The design problem was how to organize the joint facility administratively.

Objectives1

Primary Goals

Primary Goal of the Center

Deliver a prompt, high-quality computing service to clients with a wide variety of applications and a wide range of sophistication.

Primary Goal of the Organization Design

Develop a smooth-running governance plan for a joint computer center owned equally by three different institutions with different needs and objectives.

Other Objectives

• Maintain the financial stability of the center.

• Ensure that decisions are made efficiently and expeditiously.

• Ensure that each owner’s users get a fair share of all resources.

• Ensure that each owner’s financial investment is protected.

• Ensure that no owner loses on an issue of critical self-interest.

• Enable the center to operate as a single center, not three partitions, for economies of scale—one staff, one set of equipment, one job stream.

• Enable owners to change their contributions to the joint center and thereby get more or less service.

Opportunities

Economies of Scale

At the time of design, the economies of scale of running one big center instead of three little ones were substantial. They consisted of staff savings—especially important for 24-hour operation—and computer rental savings, since computers, memory, disks, and other I/O devices all followed square-law performance/price curves.

Teleoperation Possible

New technologies available with the new third-generation computers for the first time made it possible to submit and receive computing jobs remotely and to hold interactive computing sessions remotely.

National Prototype

By moving swiftly, TUCC could pioneer a model of a joint regional computing center. A big center would be nationally visible and add to the visibility of North Carolina’s relatively new Research Triangle. A new prototypical organization would reinforce an existing reputation for innovation and for uncommon local cooperation among universities.

Attract Government Support

The economies of scale could attract extra U.S. government support because the novel concept offered increased value for money to funding agencies. Moreover, the pioneering nature of the model would also attract the attention of funders.

Attract Industrial Support

The scale and national visibility of a joint center would make it a likely candidate for substantial support from industry.

Constraints

Speed of Operating Decisions

Daily operations had to be managed crisply and efficiently.

Frequent Capacity Upgrades Necessary

Both demand and funding were expected to increase rapidly, so configuration changes would have to be made routinely and responsively.

Protection of Owners’ Different Vital Interests

Duke, as the smallest of the institutions, had to be sure it wouldn’t be called on to contribute more than it could afford. NCSU, as the heaviest user, had to be sure it could count on needed capacity. Duke had to be sure the two state-owned branches of the UNC system would not vote together to private-institution Duke’s disadvantage.

TUCC Budget Stability

TUCC itself must make moderately long-term commitments (leases, officer contracts), so it had to be assured of budgetary stability.

Owners’ Budget Stability

The owners’ own budgetary processes required long lead times for any increase in TUCC’s funding.

University CEOs with a Lot at Stake

Each owning university’s CEO stood to benefit by enhancement of the Research Triangle. Each was responsible for the self-interests of his own institution.

University CEOs with Little Time to Participate, but Authority Not Delegated

Not all campuses had chief information officers with authority to commit the campus, so decisions might be slow.

Some Fractious and/or Stubborn Individuals

Some of the players had reputations of being strong-willed and stubborn.

Design Decisions

Careful Separation of Policy and Operations

Policy was to be determined by a board of directors, meeting monthly; operating decisions were to be made by a staff under a CEO, the Director of TUCC.

Board Composition

The board had to be small enough to work, but big enough to represent various segments of each campus. We ended with ten members—three chosen by and from each owning campus, plus the TUCC Director. The Director of the North Carolina Computer Orientation Project also had a seat at the table. Since NCCOP was housed in the TUCC building, its Director had substantial informal influence on what happened.

Voting Alternatives Considered for the Board

• Unanimous consent of members

• Simple majority of members

• Unanimous consent of institutions, each institution vote decided by a majority of its board members

• Majority of institutions

Unanimous Consent Not Required

We decided early on that the unanimous consent of members would make it too hard to get decisions. Avoiding the requirement of consensus greatly eased decision making.

Majority of Members Rather than Majority of Institutions

We decided that we wanted to encourage the board to think as a unit, and to discourage division according to institutional affiliation. Hence we specified that normal decisions would be made by a simple majority of the directors present and voting.

“Issues of Fundamental Importance.”

These were explicitly recognized as requiring more than normal consensus and were spelled out in the By-Laws:

• Selection or discharge of a TUCC Director

• An annual budget increase of more than 10 percent

• Modifying the Articles of Incorporation or the By-Laws

A unanimous vote by the owning institutions was required for Issues of Fundamental Importance. Note that this did not require all members of the board to agree even in such a case. Two-thirds of any owner’s delegation decided its vote.

Escape Hatch

Any owner institution could declare any issue to be an Issue of Fundamental Importance, requiring unanimity by institutions. This procedure was made suitably onerous—the institution’s representatives could table an issue for a month. Then the institution’s CEO could by letter elevate the matter to Issue of Fundamental Importance status. So any institution could, with deliberate effort, stop any action it deemed inimical to its vital interests.

Rotating Chairmanship

The chairmanship of the TUCC board rotated, with two-year terms, among the owners.

Rationing Power

In all of these decisions, thought had to be given to the rationing of power:

• Between staff and board

• Between majority and minority, by institutions and fractious individuals

• Between academic users and administrative users

Assessment

Firmness

Durability

The TUCC organization worked through 18 years, two Directors, three generations of computer mainframes, and substantial shifts away from the three-equal-owner-users model.

Escape Hatch

It was never used, as I recall. Its presence was a great psychological comfort and, I think, avoided sessions in which any group felt trapped and forced to fight for its life.

Operation as a Single Entity

The staff, as expected, operated as a single enterprise. So did the board, a gratifying outcome. Only rarely did divisions occur along institutional lines. Differences of opinion more often divided the board along faculty/administrator or bold/conservative lines.

Usefulness

Model Flexibility

As NCSU’s usage increased, various ad hoc arrangements were adopted whereby it put in more money for specific capacity enhancements (for example, more memory) in return for an increased usage share of the whole resource. Such political devices long preserved the form, if not the substance, of the three-equal-owners premise under which TUCC was begun. After the minicomputer revolution, Duke usage declined. Much computing service at Duke went to departmentally managed minicomputers.

Finally, the notion of unequal shares was formalized. The sticky point was equal versus proportional representation on the board. This was resolved by defining a use-fraction that would trigger another representative.

Tension between On-Campus and TUCC Computing Capacity

From the beginning, each TUCC owner had also a campus computing center with a staff to help its users, and hardware for entering input and printing output from TUCC. This hardware also (unavoidably) had the capacity to run some of the campus’s jobs.

Each campus center director therefore faced continual decisions as to how much of his budget to put into TUCC capacity and how much into the on-campus facility.

NCSU tended to meet most user needs at TUCC, satisfying its growth requirements by buying an ever-larger share of the growing TUCC resource. Duke tended to meet most of its needs with its declining share of TUCC—that one-third initial share was a big fraction of the Duke computing budget. UNC continued to use its third of the growing TUCC resource, but it tended to meet its excess growth requirements by building up the on-campus installation rather than by enlarging its share of TUCC.

Lessons Learned

1. Careful and explicit identification at the beginning of the vital interests of each of the three university partners and of the central facility’s director was a big help in arriving quickly at agreed-upon organization mechanics.

2. Providing an ultimate appeal procedure, though not easy to invoke, assured each participant that it wouldn’t be trodden upon.

3. Recognizing that there were differing interests within each partner, and hence getting their representation in each partner’s delegation, paid off. To a surprising degree, divisions of opinion on many issues were by area of responsibility, rather than by school: the finance-house representatives from all three of the schools often voted together, as did the three campus-computer-center representatives, and the three faculty-user representatives.

I do not remember that any steps were taken to ensure that each campus delegation would represent these several interests, but the several administrators who appointed each delegation were wise enough to get it right.

4. It is easy for a governing board for such an enterprise to become just a rubber stamp for the management. We found it necessary to meet monthly to avoid this hazard.

5. Some CEOs tend to fill board meetings with presentations, rather than discussions of real issues. Perhaps CEOs overestimate the untoward consequences of being overridden if a CEO takes a real issue to the board.

Nor, in my experience, do many CEOs use their board members severally, as advisers in their areas of expertise. I think this a real loss.

Notes and References

1. The By-Laws of the Triangle Universities Computation Center are posted on the Web at http://www.cs.unc.edu/~brooks/DesignofDesign.