5 The role of the informal in the formal sphere

Introduction

In a full-blown formal market economy, most goods and services would be produced, sold and distributed in the formal marketplace. This would mean that the vast majority of people would be in formal jobs since, to earn money to purchase the goods and services they need, they would have to earn money in the formal economy to purchase them. In this chapter, therefore, we first evaluate employment participation rates in post-Soviet/socialist economies to show the share of the population engaged in formal employment. This will reveal not only the small proportion of the population that directly participates in the formal market economy, but also how there are increasingly blurred edges between the private, public and third sectors, given that private sector organisations are increasingly pursuing a triple bottom line, while public and third sector organisations are also pursuing profit (albeit in order to reinvest so as to achieve wider social and environmental objectives).

Second, we then show that a large proportion of those apparently engaged in formal employment both in the formal market economy and the public and third sectors are in fact often not engaged in formal employment in its pure form, but rather quasi-formal employment; it appears to be formal employment but is not quite. Put another way, we will reveal that a large number of formal employees working for formal employers with formal work contracts actually receive two wages, an official declared wage and an unofficial undeclared (‘envelope’) wage. In the third section, we then extend the analysis of the illegitimate nature of formal employment beyond the issue of envelope wages to evaluate the extent and character of workplace crime in these post-Soviet societies, from cradle to grave. This will analyse how informality pervades formal provision in kindergartens, schools, universities, entry to the labour market and healthcare. The concluding section then argues that not only is the formal economy in general, and formal market economy in particular, a much smaller proportion of the whole economy than has been popularly assumed, but even those people counted as being engaged in formal employment are often engaged simultaneously in illicit practices. The outcome will be to highlight not only the shallow and uneven permeation of formal employment in contemporary post-Soviet spaces, but also how the formal market economy often blurs into more illicit work practices.

Participation in formal employment in post-Soviet/socialist economies

In 2010 in Central and Southeastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the employment participation rate among the working-age population was 59.2 per cent. This means that four in every ten people of working age in the post-Soviet/socialist world were not participating in the formal economy. As Table 5.1 displays, moreover, there are significant cross-national variations. Even in Kazakhstan, the country with the highest employment participation rate, one in four people of working age do not participate in the formal economy. In Moldova, meanwhile, just 46.4 per cent of the working-age population are in formal jobs, meaning that the majority of the working-age population do not participate in the formal economy.

Table 5.1 Labour force participation rate (15–64 years old), 2010 in post-Soviet/socialist societies

| Country | Percentage of working-age population in formal jobs |

Kazakhstan | 77.4 |

Estonia | 74.0 |

Latvia | 73.7 |

Russian Federation | 72.9 |

Slovenia | 71.2 |

Lithuania | 70.7 |

Kyrgyzstan | 69.9 |

Czech Republic | 69.7 |

Tajikistan | 68.7 |

Slovakia | 68.7 |

Georgia | 67.7 |

Ukraine | 67.2 |

Bulgaria | 67.0 |

Albania | 66.5 |

Poland | 65.6 |

Croatia | 64.5 |

FYR Macedonia | 64.4 |

Uzbekistan | 63.9 |

Romania | 63.8 |

Armenia | 63.7 |

Turkmenistan | 63.6 |

Serbia and Montenegro | 63.5 |

Hungary | 62.3 |

Bosnia and Herzegovina | 54.5 |

Moldova, Republic of | 46.4 |

Source: ILO Key Indicators of the Labour Market (KILM), http://kilm.ilo.org/kilmnet.

It is not only participation in the formal economy that is relatively shallow in post-Soviet societies. Contrary to the perception that there has been a shift towards formal market economies in post-Soviet societies, this is not borne out by the evidence on participation rates in formal jobs in the private sector. In the 313 households surveyed in Moscow, only 37 per cent of the surveyed population had participated in the year prior to the survey in paid formal labour registered by the state for tax, social security and/or labour law purposes and just 22 per cent in formal labour in the private sector, although participation rates are higher in affluent than deprived populations (see Table 4.5). Similarly, in the 600 households surveyed in Ukraine, just 56 per cent had participated in the year prior to the survey in paid formal labour and just 26 per cent in formal labour in the private sector. Despite all of the hyperbole about the shift towards a formal market economy, therefore, less than one-quarter of the surveyed population in Ukraine and the Russian city of Moscow work in this sphere.

Indeed, even these figures on participation rates in private sector formal employment possibly exaggerate the incursion of the formal market economy in its ‘pure’ profit-motivated form. This is because even those participating in employment in the private sector cannot increasingly be seen as engaged in purely capitalist modes of production, if by that one means the production and exchange of goods and services for monetary exchange in order to make a profit. This is because many private sector businesses in post-Soviet societies are increasingly pursuing a ‘triple bottom line’ in the sense that profit is not their sole motive and they are instead also pursuing social and environmental goals, as displayed by the widespread adoption of corporate social responsibility (CSR) into their visions and missions. Over the past decade or so, firms in both Russia and Ukraine have been increasingly turning their attention to not only pursuing profit, but also striving to respond to the environmental and social needs of their respective communities and societies (Basharina 2008; Crotty and Rodgers 2012; Kuznetsova and Kuznetsov 1999; Koleva et al. 2010; Kolot 2012; Kurinko 2011; Kuznetsov and Kuznetsova 2003; McCarthy and Puffer 2003, 2008).

The result is that there is a blurring of the private, public and third sectors within the formal economy in post-Soviet societies. Private sector organisations are increasingly pursuing a triple bottom line, while public and third sector organisations are also pursuing profit (albeit in order to reinvest so as to achieve wider social and environmental objectives), resulting in a blurring of the boundaries between these three spheres of the formal economy. To identify a separate purely profit-motivated formal market economy, therefore, separate from the public and not-for-profit sectors, is an increasingly difficult task. Formal paid employment as a whole, moreover, is not discrete and separate from the informal economy since it is often infused with informality in post-Soviet states. As will now be revealed, much of what appears superficially to be formal sector employment is not quite as formal as it first appears when one delves deeper into the employment contracts that many formal employees have with formal employers in post-Soviet societies.

The illusion of formalisation: the prevalence of quasi-formal employment

A long-standing and recurrent assumption has been that formal jobs are entirely separate from informal jobs. Jobs are widely depicted as either formal or informal. Reflecting the formal/informal economy dualism, the idea that a job might be simultaneously both formal and informal has been rarely considered. Since the turn of the millennium, however, this dichotomous portrayal of jobs as either formal or informal has started to be contested. A small but burgeoning literature focusing on post-Soviet spaces has begun to reveal that formal employers sometimes pay their formal employees both an official declared salary as well as an additional undeclared salary, or what is termed an ‘envelope wage’, which is hidden from, or unregistered by, the state for tax and social security purposes. Such studies of envelope wages have been undertaken in Estonia (Meriküll and Staehr 2010), Latvia (OECD 2003; Meriküll and Staehr 2010; Sedlenieks 2003; Žabko and Rajevska 2007), Lithuania (Karpuskiene 2007; Meriküll and Staehr 2010; Woolfson 2007), Romania (Neef 2002), Russia (Williams and Round 2007) and Ukraine (Round et al. 2008; Williams 2007).

The principal rationale for formal employers paying an envelope wage to their formal employees is so that they can evade their full social insurance and tax liabilities by paying a portion of their formal employees’ salaries as an envelope wage. Nevertheless, although this is the main reason for using this illicit wage arrangement, it is not the only one. It is also a useful tool for formal employers when seeking to make a formal employee redundant. By refusing to pay their envelope wage, formal employers can encourage those formal employees they no longer wish to retain to voluntarily leave their formal job, thereby enabling the employer to evade social costs in the form of redundancy pay (Hazans 2005; Round et al. 2008).

Why, therefore, are envelope wages more common in some post-Soviet/socialist societies than others? In order to explain this, two alternative explanations can be adopted. On the one hand, and from a neo-liberal economic perspective, it might be argued that such illicit wage payments are a product of high taxes, over-regulation and state interference in the free market. From this viewpoint, therefore, such illicit wage payments would be more prevalent in countries with higher taxes and levels of state intervention in work and welfare systems, and are a response to over-regulation (Becker 2004; De Soto 1989, 2001; London and Hart 2004; Nwabuzor 2005; Small Business Council 2004). As Becker (2004: 10) puts it, ‘informal work arrangements are a rational response … to over-regulation by government bureaucracies’. To resolve the problem of envelope wages, therefore, tax reductions, deregulation and minimal state intervention would be pursued.

On the other hand, and from a social democratic structuralist perspective, it could be argued that these illicit wage payments by employers are a product of the lack of regulation of labour markets and inadequate levels of labour market intervention and social protection. For structuralists, in consequence, the contemporary mode of production is one where businesses are employing informal modes of organising and organisation so as to achieve flexible production, profit and cost reduction (Castells and Portes 1989; Davis 2006; Gallin 2001; Sassen 1996; Slavnic 2010). Viewed through this lens, envelope wages are one manifestation of how this is being achieved. Besides sub-contracting various stages in the production process to the informal economy, formal employers are also achieving flexible work arrangements, profit and cost reduction by paying formal employees some of their wage as an undeclared envelope wage. Those in receipt of such envelope wages are thus seen as unfortunate and unwilling pawns who out of necessity are forced into this illegitimate wage practice (Ahmad 2008; Gaetz and O’Grady 2002; Ghezzi 2010). Envelope wages therefore arise in this perspective due to the lack of regulation in the economy, and greater regulation is required to resolve this problem. As such, this illicit wage practice would be less prevalent in post-Soviet/socialist countries with higher levels of state intervention in work and welfare systems.

To evaluate these competing views, the prevalence of this wage practice will be analysed in more neo-liberal post-Soviet/socialist regimes with lower levels of state intervention and in more ‘welfare capitalist’ post-Soviet/socialist economies where there is greater intervention in work and welfare in order to evaluate two hypotheses:

- Envelope wage payments are more popular in countries with higher tax rates.

- Envelope wage payments are more popular in countries with greater levels of state intervention in the economy and welfare provision.

To do this, we here report the 2007 Eurobarometer survey which examines the prevalence of envelope wage arrangements in the ten East-Central European member states belonging to the European Union (TNS Infratest et al. 2006; European Commission 2007). Some 10,171 face-to-face interviews were conducted in these ten East-Central European economies, namely Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia and Romania.

This face-to-face interview first asked those who reported that they were formal employees:

Sometimes employers prefer to pay all or part of the regular salary or the remuneration for extra work or overtime hours cash-in-hand and without declaring it to tax or social security authorities. Did your employer pay you all or part of your income in the last 12 months in this way?

Second, in order to comprehend the nature of envelope wage payments, they were asked:

Was this income part of the remuneration for your regular work, was it payments for overtime, or both?

Third, they were asked to estimate the percentage of their gross yearly income from their main job received as an undeclared envelope wage; fourth, they were asked whether they were happy to receive a portion of their salary as an envelope wage. Here, and in order to answer the research questions above, data on cross-national variations in tax rates, levels of social protection and the degree of state redistribution via social transfers are integrated into this dataset on envelope wages.

The extent of quasi-formal employment in post-Soviet/socialist societies

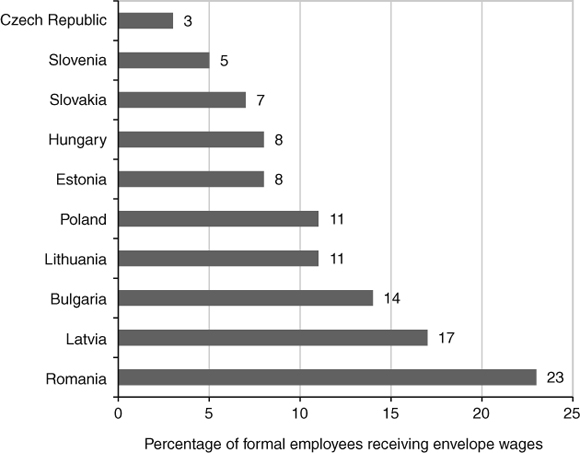

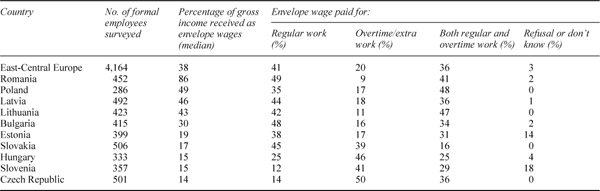

Of the 10,171 face-to-face interviews conducted in these ten East-Central European economies, 4,164 participants reported that they had formal jobs. Of these 4,164 formal employees, one in eight (482 employees in total) had received an envelope wage from their formal employer over the past 12 months. If extrapolated to the population of these ten countries as a whole, this intimates that, scaled up, some eight million employees in these East-Central European countries receive envelope wages. The prevalence of this illicit wage arrangement, however, is not evenly distributed across these East-Central European nations. As Figure 5.1 displays, there are marked cross-national variations, ranging from 23 per cent of formal employees in Romania reporting that they receive an envelope wage to just 3 per cent of formal employees in the Czech Republic.

Nor is the nature of these envelope wage arrangements the same in all ten countries. As Table 5.2 reveals, across all ten countries, those paid envelope wages receive 38 per cent of their total wage illicitly, but this ranges from 86 per cent in Romania to 14 per cent in the Czech Republic. There are also variations in whether formal employees are paid an envelope wage for their regular work and/or for overtime conducted. In Romania, Poland, Latvia and Lithuania, for example, the vast majority of employees receive envelope wages for their regular work and/or both regular work and overtime, while in countries such as the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovenia, nearly half of the recipients of envelope wages receive them for overtime or extra work conducted.

Table 5.2 Characteristics of envelope wage arrangements in East-Central Europe

Source: Eurobarometer survey of undeclared work, 2007.

On the one hand, therefore, there are a group of East-Central European countries in which this envelope wage practice is extensive, paid to employees more for their regular hours, and it amounts to, on average, around one half of formal employees’ wages (i.e. Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania). On the other hand, there are a group of East-Central European countries where envelope wages are less common, paid more for overtime or extra work and amount on average to just one-fifth of employees’ gross wage (i.e. Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, Hungary and Estonia). How, therefore, can these cross-national variations be explained? Are envelope wages more common in ‘welfare capitalist’ societies in which there is greater interference in the economy and welfare? Or is it more common in neo-liberal regimes where intervention in work and welfare is much lower? To evaluate this, first, the relationship between envelope wages and tax rates, and second, between state intervention and envelope wages, will be evaluated. This will allow conclusions to be reached on the validity of the neo-liberal and structuralist explanations regarding whether envelope wages are correlated with over-or under-regulation.

Relationship between national tax rates and quasi-formal employment

The neo-liberal perspective argues that envelope wages are a direct result of high tax rates and that the consequent remedy is to reduce taxes in order to decrease their prevalence. To evaluate this, first we here examine the relationship between envelope wages and the implicit tax rates (ITR) on employed labour in these ten East-Central European member states of the European Union (Eurostat 2011). This, in effect, is a summary measure of the average effective tax burden on labour income. It is the total of all direct and indirect taxes and employees’ and employers’ social contributions levied on employee income divided by the total compensation of employees. Direct taxes on labour income cover the revenue from personal income tax, while indirect taxes on labour income are taxes such as payroll taxes paid by the employer. Employers’ contributions to social security (including imputed social contributions) and to private pensions and related schemes are also included. The compensation of employees is the total declared remuneration, in cash or in kind, payable by an employer to an employee. It is thus the gross (declared) wage from employment before any charges are withheld (Eurostat 2007).

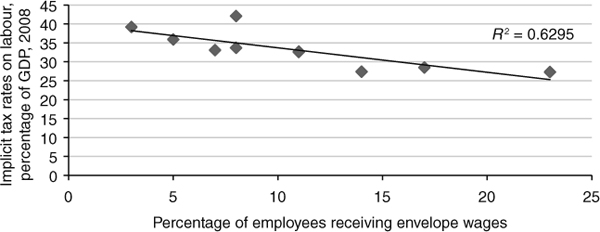

Figure 5.2 graphically displays the relationship between the cross-national variations in the prevalence of envelope wages and the variations in implicit tax rates on labour (i.e. the average effective tax burden on labour income) across these East-Central European countries. Using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs), the finding is that there is a strong significant correlation between the cross-national variations in the average effective tax burden on labour income and cross-national variations in the prevalence of envelope wages across East-Central Europe (rs = –0.872**). Indeed, 63 per cent of the variance in the prevalence of envelope wages is correlated with the variance in implicit tax rates (R2 = 0.6295). However, the direction of the correlation is not in the direction suggested by neo-liberal thought. The prevalence of envelope wages does not rise with increases in the effective tax burden on employed labour. Instead, quite the opposite is the case. Consequently, the neo-liberal representation that envelope wages directly result from high taxes, and that the remedy is to therefore pursue tax decreases, is refuted.

In consequence, envelope wages are significantly correlated with the effective tax burden on employed labour but not in the way neo-liberals assert. Instead, the finding is that as the effective tax burden on employed labour increases, the prevalence of envelope wages declines. Nations with higher ITRs on labour income witness lower levels of envelope wage payments. To begin to better understand this, we now turn to examining the relationship between envelope wages and different work and welfare regimes.

Relationship between state intervention and quasi-formal employment

Is it the case that nations with greater levels of state interference have higher levels of envelope wages, as neo-liberals assert? Or is it that nations with greater state intervention have lower levels of envelope wages, as the structuralist perspective asserts? To answer these questions, the correlation between the cross-national variations in the prevalence of envelope wages and the cross-national variations in, first, the extent of state labour market interventions as a proportion of GDP, second, the level of social protection expenditure as a proportion of GDP and, third, the impact of state redistribution, will be analysed.

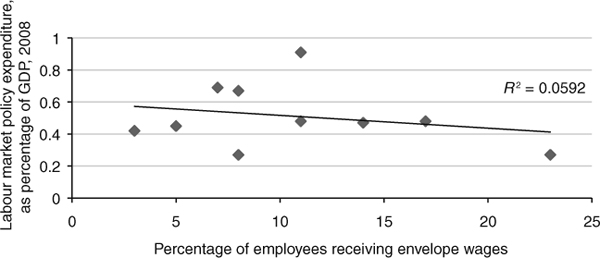

To evaluate whether greater intervention in the labour market is correlated with an increase or decrease in the prevalence of envelope wages, a bivariate analysis is conducted of the cross-national variations in the prevalence of envelope wages and the cross-national variations in the level of spending on labour market interventions to correct disequilibria, explicitly targeted at groups of the population with difficulties in the labour market, such as those who are unemployed, in employment but at risk of involuntary job loss, and inactive persons currently excluded from the labour force but who would like to join the labour market but are somehow disadvantaged (Eurostat 2011). As Figure 5.3 displays, there is no significant correlation between the cross-national variations in the proportion of GDP spent on labour market policy measures and the cross-national variations in the prevalence of envelope wages (rs = –0.012), with 6 per cent of the variance in the prevalence of envelope wage payments correlated with the variance in the proportion spent on labour market interventions (R2 = 0.0592). Therefore, there is no support for the neo-liberal explanation for the cross-national variations in envelope wages. Neither, however, is there any support for the structuralist perspective that there is a significant correlation between higher levels of state labour market policy expenditure and reductions in this illicit wage arrangement.

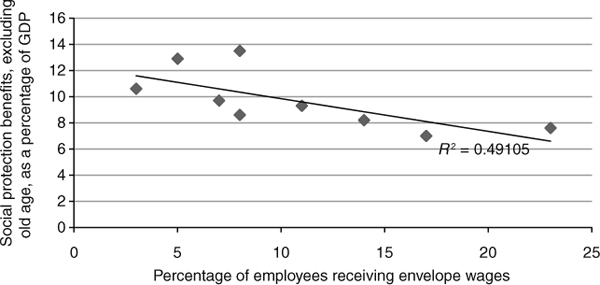

Examining the relationship between cross-national variations in the prevalence of envelope wages and the degree of intervention in welfare, as measured by the proportion of GDP spent on social protection benefits, excluding old-age benefits (European Commission 2011: table 3), stronger correlations can be identified. As Figure 5.4 displays, there is a very strong statistically significant correlation (rs = 0.832**), with 49 per cent of the variance in the prevalence of envelope wages correlated with the variance in the proportion spent on social protection (R2 = 0.491). However, it is not in the direction intimated by neo-liberal thought. Post-Soviet/socialist countries where a higher proportion of GDP is spent on social protection have a lower incidence of envelope wage payments. Consequently, a higher level of state intervention in the form of social protection is correlated with a decrease in envelope wage payments, as suggested by the structuralist perspective.

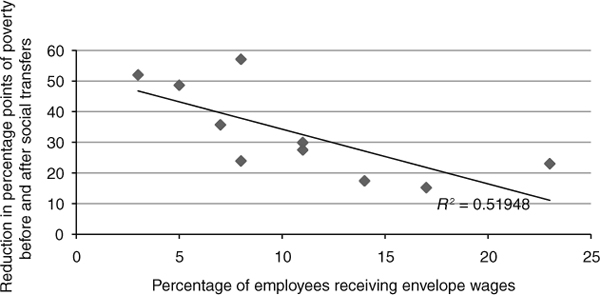

This correlation between greater state intervention and a decrease in the prevalence of envelope wages is further reinforced when the redistributive impacts of state intervention are evaluated. Examining the reduction in percentage points of poverty before and after social transfers, with poverty defined as the proportion of people with an income below 60 per cent of the national median income (European Commission 2011: table 3), Figure 5.5 shows that member states where social transfers have a greater impact on reducing poverty have lower proportions of formal employees receiving envelope wages, not larger numbers as neo-liberals intimate. This is a very strong statistically significant correlation (rs = –0.817**, R2 = 0.5195).

In sum, no evidence has been found to support the neo-liberal view that envelope wages arise due to high taxes. Neither has any evidence been found to support the neo-liberal view that greater levels of state interference lead to higher levels of this illicit wage arrangement. Instead, the finding is that greater state intervention in the form of social protection and redistribution is significantly correlated with a reduction, rather than increase, in the prevalence of envelope wages. These findings thus raise grave doubts about whether deregulation, tax reductions and minimal state intervention is the way forward by showing that the problem appears to be not one of over-regulation, but rather under-regulation.

Until now, however, little attention has been paid to how envelope wage arrangements are experienced on the ground by employees and employers. It is to this that attention now turns.

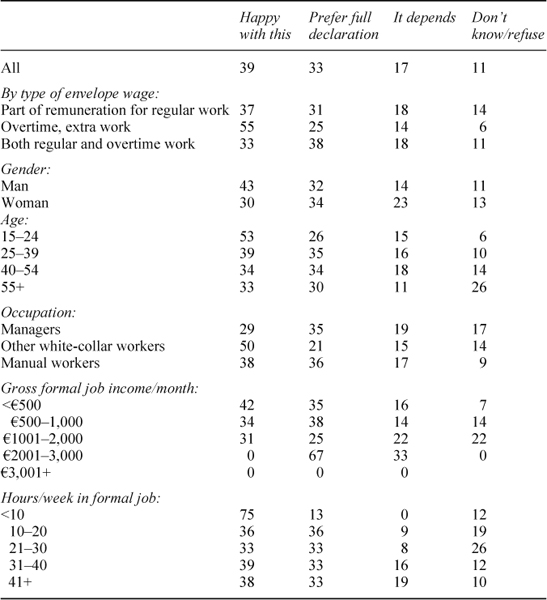

Lived experiences of quasi-formal employment

Are those receiving envelope wages happy to do so? Given that they potentially receive higher wages than if employers had to deduct the tax and social insurance contributions, one might believe that employees would be content with this arrangement. However, Table 5.3 reveals that just two in five (39 per cent) employees receiving envelope wages are happy to do so. A third (33 per cent) would prefer full declaration and the remaining 28 per cent are either undecided or refused to answer. Their attitude, nevertheless, largely depends on whether such payments are for regular hours worked or for overtime. Contentment was highest among those receiving such wages for extra work or overtime hours; 55 per cent are happy with this arrangement. Employees receiving envelope wages for their regular work, or for both their regular work and overtime hours, are less happy and would prefer full declaration.

Employees’ attitudes towards envelope wages, moreover, also vary across different population groups. Men, younger age groups, those earning lower formal wages and working low hours are more content receiving an envelope wage than other groups. However, this is largely because these groups are most likely to receive envelope wages for overtime or extra work rather than for their regular hours.

During the fieldwork in both Ukraine and Moscow, further understanding of this lack of contentment with envelope wage payments was sought. In major part, the finding is that it is because when their official declared wage is lower than their actual wage, it prevents them accessing their full entitlement to social security and pension payments and constrains their ability to get credit, loans and mortgages (Williams 2007; Williams and Round 2007). Indeed, this dissatisfaction with receiving envelope wages, especially for regular work, clearly signals that the decision to pay envelope wages is not reached cooperatively and amicably between the employer and employee. It appears to be largely imposed on employees by employers. Many employees would prefer to receive their regular salary (as well as overtime payments) on a declared basis, but their employer obliges them to receive a portion as an envelope wage. Indeed, in the 600 face-to-face interviews conducted in Ukraine, the finding was that 30 per cent of formal employees were paid envelope wages by their employer. Although sometimes this cash-in-hand element was received for overtime, most of the time it was not. They were receiving a proportion of their regular salary in this manner. Very few employees were happy with this arrangement as receiving part of their wages in this manner affected their social security and pension entitlements as well as their ability to apply for visas to travel abroad and get credit, since their official wage was lower than their actual wage. Although such a practice is common in Ukraine, the formal procedures of various institutions such as banks do not take it into account formally when making decisions on loans (even if informally they do so). As one respondent seeking a mortgage recounted, the bank informed him that he would need seven guarantors due to his ‘low’ wages. Getting seven people together was not a problem for him, but as he stated:

All my work colleagues had pieces of paper with them that said they earn only US$400 per month which was not enough for the bank. However, all seven had SUV vehicles parked outside of the building – we had to take the bank manager outside to show them to him and say ‘this is what we really earn’ – in the end they agreed to give me the loan.

Similarly, the 313 face-to-face interviews conducted in Moscow also revealed the widespread prevalence of envelope wage payments; nearly one-third (30 per cent) of the formal employees interviewed received envelope wages amounting to, on average, 40 per cent of their total wage. Indeed, 35 per cent of men and 25 per cent of women in formal jobs receive envelope wages. There was no difference between women and men, however, in terms of the proportion of their total wage paid as an envelope wage, which is largely not for overtime, but part of their regular salary. This is not just the case for the ‘budjetniki’, including doctors, the police, teachers, nurses and so on who earn 4,000–10,000 roubles (£80–300) per month, but across the income spectrum. Few receiving this envelope wage, however, see this as beneficial. Nor is it a chosen practice. Nearly all employees receiving it asserted that it was imposed on them by their formal employer. The extensiveness of this labour practice, therefore, reveals that the formal economy is infused with informality in Moscow. Many formal employees in Moscow are in jobs that are at the formal–informal border.

Given that envelope wages have significant implications for pension entitlements and social protection, some two-thirds receiving envelope wages were opposed to receiving such ‘tax-free’ wages precisely for this reason. As one man in his mid-forties working in the home improvement sector stated, ‘Due to my low “official” wage, none of the banks wanted to lend me the amount I wanted for my mortgage. I told them about my envelope wages but they didn’t include it. It’s crazy.’

On the whole, however, banks are perhaps correct not to do so. One-quarter (25 per cent) of the participants interviewed receiving envelope wages had experienced difficulties in receiving this wage. As a woman in her late twenties, who had worked as a manager in a large Russian pharmaceutical company, explained:

They said that my formal salary would be 5,000 roubles a month but the real wage would be up to US$2,000… . At the end of the month they paid me my formal 5,000 roubles and said that I would get all the ‘additional money’ the next month … but the next month nothing changed. I got my formal salary again and a promise that the next month the company would compensate my efforts and I would get ‘my off-the-books additional income for 3 months’. By that time I had talked to other people who worked there. They said that they never got what they were promised. Something like once every 4 months, the company would pay them about US$500 as additional income with promises to pay the rest next time. The more the company owes a worker, the more the pressure they put on them. They have developed a system of fines and look for tiny little mistakes in the work (like somebody coming back from their lunch break one minute late) and then fine them US$50. So in the end the company does not owe anything and the worker feels grateful for the additional US$500 once every 4 months. I did not have any fines so I just left.

Again, there are no differences between women and men in witnessing such difficulties. It is important to realise, however, that three-quarters received their envelope wages without problems. As a woman in her mid-forties stated,

I write computer programs for a well-known company… . My formal salary is 6,000 roubles (£120) a month, but my real income is about 30,000 roubles (£600) a month. I have never had any problems with my envelope wage. The company pays it regularly.

In sum, envelope wages are a popular practice in post-Soviet/socialist societies. Some one in eight formal employees receive an envelope wage, and this on average amounts to 38 per cent of their wage packet. The result is that even if 59 per cent of the working-age population are engaged in formal employment in post-Soviet/socialist societies, some one in eight of these are in quasi-formal jobs. This not only blurs the divide between formal and informal jobs, but also means that the proportion in purely formal employment is even lower than previously assumed. This, however, is not the only way in which the formal economy is infused with informality. Here, attention turns towards the extent and character of workplace crime in post-Soviet societies.

Crime and corruption in the formal economy: informal payments from cradle to grave

As the above discussion of quasi-formal employment has shown, formal employment is often infused with informality. In this section we extend this discussion of how the formal economy in post-Soviet countries is permeated by informality by examining how crime and corruption is witnessed in dealings with the formal economy from cradle to grave. One of the abiding features of crime and corruption in post-Soviet spaces is its closeness to everyday life. Informal payments are expected from, or on behalf of, all ages and sectors of society, from the registration of births, to accessing free kindergarten places, entering university, securing employment and healthcare through to securing a well-sited burial plot. While such payments ‘grease the wheels’ of the system and provide incomes to low-paid workers, they are also opportunistic and predatory actions, engendering a culture of informality throughout the society and lead to a system where those paying come to see such payments as an ‘investment’ which will be earned back at some point in the future. To see this, we commence this section by looking at the prevalence of informal payments surrounding kindergartens, followed by schools, universities, entry to the graduate labour market and the realm of healthcare services, thus displaying the permeation of the formal economy by informality from cradle to grave.

The informal economies of kindergartens

Whereas the Soviet system provided preschool education, this is no longer the case. As Zdravomyslova (2010) makes explicit, since the collapse of the Soviet welfare system, in Russia whilst nursery schools remain, there is not enough space available for existing demand. The federal government states that regional authorities should provide free entrance to kindergarten for all children. Yet the shortage of places sees fierce competition for places at kindergartens. Whilst such places are officially ‘free’, in practice this is rarely the case. They are often now either not financed by the state budget at all or only part financed. As such, parents are required to pay. Alongside ‘state-run’ nurseries there has been witnessed the rapid growth of wholly commercial nursery schools, especially in Moscow and Russia’s large urban centres.

The gap between the formal state provision of childcare and the increasing demand for places has inevitably led to strains on the system and the manifestation of informal payments as a means to facilitate gaining a place in a nursery school. Gradkova (2010: 181) discusses how the majority of her respondents had to make informal payments to ensure a space for their child ‘ranging from a hundred to several thousand dollars’. As well as direct informal payments, parents are often asked for gifts for the school to ensure admittance (Oberemko 2006).

Once within the kindergarten, the requests for payment do not stop. These can include items for the children, such as books and/or furniture, and direct gifts to the teachers (Gradkova 2010). As one of our interviewees in Moscow asserted:

The payments we have to make to the kindergarten are non-stop. There is always something that needs fixing or replacing. We also have to spend time making repairs or clearing the snow in the winter. It would be interesting to know where the money that the government provides for these services goes… . Of course we cannot say anything as we want the best treatment for our child and we just give in to every request.

Clearly not all households can afford such payments, leaving an increasing number of children without childcare places, with Gradkova (2010) estimating that 27.5 per cent of children in urban areas cannot attend preschool because of the lack of places. A lack of a place puts enormous pressure on the household as school does not start until the child is 6–7 years old. One response, which was observed in both affluent and deprived areas, was for several households to share childcare, creating informal kindergartens:

Several people in our circle got talking about how finding a place at kindergarten was so difficult so we decided to share child care. I like looking after kids so during the day I look after the children of four of my friends. Obviously I cannot go to work but my friends give me money from their salary and give me materials for the children’s activities.

When asked if they would ever formalise the practice, they stated,

Of course not! The reason we do this is to escape all of the payments we are supposed to make. If we made it formal then we would have to pay bribes to get the licences and we would have to pay tax. It is much better to keep everything small and out of sight.

While this is clearly a satisfactory arrangement for those concerned with high levels of trust involved, these households are making payments or spending time on services which should be free at entry and then low cost each month, putting further pressure on household budgets.

Informality in the formal school system

Such informal payments for formal sector provision do not end when the child enters school. Although entrance to state schools is free, interviewees discussed how informal payments were solicited from institutions with a high demand for places (Osipian 2011). Although the majority of this concerns corruption around university entrance exam schemes (considered further below), bribes are still a regular occurrence within the secondary education system. Interviewees with school children all discussed the biggest problem with informal payments was the regular requests for ‘help’ from the school. As an interviewee in Kyiv reported:

Every time we have a parents meeting we are told we need to make another payment for something that is wrong at the school. Last time we had to also bring toilet paper for the school as the head said they could no longer ‘afford’ it. No one can complain as you don’t want your child to have difficulty at school

Indeed, she then asserts that in Russia’s regions, parents annually pay between 3,000 and 20,000 roubles per year to their children’s schools. As an interviewee in Kyiv reported,

Every time we have a parents meeting we are told we need to make another payment for something that is wrong at the school. Last time we had to also bring toilet paper for the school as the head said they could no longer ‘afford’ it. No one can complain as you don’t want your child to have difficulty at school.

Nikitina (2009) lists some of the payments that parents are expected to make, including mops, toilet paper, flooring, new windows, projectors, payments for security guards, among many others. She discusses how the sum collected from the parents is much higher than the actual cost and that when one respondent asked for a receipt, her child was sent to a ‘remedial’ class. Parents are also expected to provide free labour throughout the school year. This might include the painting and repair of the school during the summer vacation to the clearing of snow during the winter. Without doubt, post-Soviet schools suffer from serious underfunding, but there is clearly the misappropriation of funds for such activities at some point in the chain.

According to the media monitoring and analysis service, public.ru, there is a price list within certain schools of payments to pass exams with good grades. For example, they state that in the Republic of Dagestan it will cost you from 500 roubles to be allowed to take your mobile phone into an exam to 10,000 roubles for the teacher to help with the exam (public.ru). The situation is exacerbated by the very low salaries of teachers in post-Soviet states. In 2012 the average salary for a secondary school teacher in Russia was 12,000 roubles per month, less than two times higher than the subsistence minimum figure. As Patico (2002) remarks, gift-giving to teachers is therefore a very common practice in Russia, and although similar practices exist everywhere, it is perhaps at a much higher level in post-Soviet states. On set days such as ‘teachers day’, 1 September (the first day of the school year) and on birthdays, it is expected that students present gifts such as flowers and chocolates. While these are welcomed by the teachers, often they are recycled as gifts, to save money, or resold to provide an income. On 1 September, when students take flowers to the teachers, flower sellers discussed with the authors how after school, many teachers sell the majority of the flowers back to the sellers for 50 per cent of their original cost. Parents, aware of the low salaries, discussed how they now purchase supermarket gift vouchers as gifts in order to supplement teachers’ income. Teachers also undertake informal work to bolster their salaries. This includes tutoring for the university entrance exam, giving private lessons after school hours, or indeed holding other cash-in-hand positions outside of teaching.

The giving of private lessons is a revealing example of the scale, and internal power, of informal practices. The authors during their fieldwork interviewed numerous teachers and became friends with some. At first glance, their informal practices seem lucrative as it was not uncommon for teachers to be informally teaching groups of 8–10 students, each paying US$5 per hour, two to three times per week. Two teachers in Moscow, for example, discussed how they quadrupled their income by providing extra English lessons in the school they work at, after formal teaching hours, to the children of ‘rich Russians’. However, many feel trapped by the process and wish to discontinue. Given the income it generates, this seemed surprising until they discussed that to do this work they have to pay cash to their bosses to be ‘allowed’ to undertake such work. In one instance, the school director was threatening to report them to the tax police if they stopped giving informal lessons. Common to the theme running throughout this book, the teachers discussed that without their informal incomes they would not be able to afford to teach. However, they all note that such practices are extremely stressful and that they wish for their lives to be more formal. This is similarly the case for those who must provide such payments, since finding this money from already tight household budgets is often very difficult. Indeed, this is perhaps why Rotkirch and Kesseli (2012: 146) assert that ‘Two children puts you in the zone of social misery’. Not only is the cost of everyday goods to feed and clothe two children very difficult to find for most, but informal payments need to be made as they progress through childhood.

Informality in the university system

As with all the discussions presented in this book, we are not here suggesting in this analysis of corruption and informality in the university system that the practices are taking place within every university or by everyone employed within them. However, from interviews with graduates and students in Ukraine and Moscow, it is clear that informal payments and corruption are very serious issues. Nor is such corruption confined to Ukraine and Moscow. It is common across numerous post-Soviet states (Heyneman 2007, 2010; Karakhanyan et al. 2011; Osipian 2010, 2011, 2012; Petrov and Temple 2004). Indeed, Forbes Russia (2012) recently reported in a country-wide survey on corruption in Russia that the higher education sector was seen as the third most corrupt state sector (46 per cent of respondents), exceeded only by the traffic police (52 per cent) and preschool education (51 per cent). As Burova and Ozmidova (2012) eloquently state, in Russia ‘[t]he corruption that exists in higher education is like a drop of water that reflects the situation in society as a whole’, with 50 per cent of students encountering it. Agranovich (2008) similarly states that 50 per cent of students believe that the only way to enter university is through paying a bribe, while Osipian (2012) states that over 30 per cent of Ukrainian students pay bribes to enter higher education and, above this, others take advantage of personal connections. As Heyneman et al. (2008) discuss, other forms of informal payments range from the Ministry of Education demanding payments from rectors for institutional accreditation to professors delaying the approval of a student’s thesis until a ‘fee’ is paid. Corruption, however, is not just limited to those within the system; as Osipian (2011) points out, there is a thriving market for simply purchasing postgraduate degrees in post-Soviet states.

Within post-Soviet states, a university degree is a prerequisite for the vast majority of jobs. As one interviewee in Ukraine commented, ‘you need a degree to get a job just picking up the telephone’. Therefore, there is intense competition for the best universities and courses in countries such as Ukraine, entrance to which is governed by competitive entrance exams. Students discussed how they were asked for bribes outright for a place or were told if they paid for tuition in how to do well in the exams, entrance would be guaranteed. Attending these sessions was, of course, optional after paying. One quite ingenious scheme was related by a senior academic whereby a ‘price’ would be given to pass the entrance exam and most students would pay it. Making the payment made no difference to the chances of success as a certain percentage would be accepted onto the course anyway. Those who did make the payment and were rejected were simply told that something had gone wrong and their money was returned. The academics then kept the money from the people who thought they had paid a bribe and thus made a significant sum for doing nothing. Nevertheless, sometimes such payments did help. As one Ukrainian student said, after refusing to make an informal payment for entrance to the city’s most prestigious university,

I got the highest score out of all the applicants for my English language exams. Yet I did not get a place. Why? Because I scored zero in my Ukrainian language exam. How can this be, I wonder, as I am fluent in Ukrainian? [said in an extremely mocking tone]

The same process happened when applying for the second-ranked university; she was only accepted without making a payment into what is considered to be the third best. Another interviewee discussed how they failed to enter their chosen course for six years as they refused to make the requested payment:

I totally refuse to pay bribes. My father was very high up during the Soviet period and he kept telling me that he could help me get in. But I did not want that. I wanted my degree to be only from my abilities. If I paid bribes or used connections how would I know my degree was worth anything?

Such examples highlight that the best students are not allocated to the best courses and institutions, which both impacts on their future careers and decreases the country’s human capital. Osipian (2012) discusses that the most popular courses in Kyiv require a bribe of between US$10,000 and US$15,000 to enter, ensuring that only the richest sections of society can access them and thus the opportunities that arise for the graduates. Within Ukraine, students are classed as either ‘budget’ or ‘contract’. The former are those for whom tuition and a stipend are paid by the university and the latter have a set yearly payment for course fees. This is obviously an area where corruption is possible. With regards to the budget places, informal payments can be made to access them, meaning that it is often the richest students who have these places. As one student stated:

Look at all the people on the budget in my course. They are all from rich families whose parents can afford to influence the correct people. They don’t need the money the stipend gives them but it is all to do with power. They can alter the system, so they do it.

Grishina and Korchinsky (2006) note one course where out of 120 budget places, 96 were allocated prior to the entrance exams, inferring that these places were bought by bribes and via connections.

Once in the university system, payments are sometimes requested to pass exams or obtain good grades. The propensity for one-to-one oral examinations facilitates this, where a payment can be requested for the desired grade, as the following student discusses:

We have such a crazy system here in Ukraine. When we have to get a zachot our professor will tell us to queue outside his office, for example, at ten o’clock in the morning. We all stand there, you know, half pretending with each other that we are worried about the exam. Yet, you know [laughing], we all know that we will simply give him some money and pass this exam. It works like that. It’s kind of like a big show, we are pretending that we have a real exam and the lecturer pretends to be examining us.

This is obviously not the case for every exam, and among interviewees there was a feeling that it tended to be older or younger less established members of staff who undertook such practices, whereas established ‘middle-aged’ academics, it is believed, can supplement their income through lecturing in numerous universities, grants or entrepreneurial activities, thus reducing the need to earn informal incomes. However, the majority of interviewees said they had encountered such practices at some point in their degree and had to comply with them:

We don’t have a choice. We either pay our lecturers and pass our exams or we risk getting thrown out. It does not matter what we know and whether we want to learn or not. It simply matters about money. What can we do? If we don’t pay and leave university, then what? In our country, a person with no qualifications has no future, no chance for progression.

The payment is often small, which is why there is more a resigned acceptance to the practice rather than widespread anger. However, over the course of a year it accumulates to a significant sum for the recipient. If the student does not want to take the exam, interviewees discussed how it would be common knowledge that there was a member of staff who could be approached, who in turn would approach the module leader. For example, in one university a member of the sports department plays this role. The payment would be made to them and they would then share it with the corresponding academic. This person also possessed knowledge about on what modules such practices were possible and which members of staff should never be approached over informal payments. On occasions, money payments would not be requested but a service provided to the university would be performed instead. For example, in one university those who had failed exams were asked to paint the university’s interior over the summer in order to ‘pass’ the retake exams without actually having to sit them. The money allocated to pay for the painting would then be split between those running this ‘scheme’.

The majority of students have to undertake part-time, or in some cases approaching full-time, work in order to support themselves during their university course. Numerous students discussed how one form of income was writing coursework assignments for richer students. While there are regular anti-corruption drives in the higher education sector within many faculties, frameworks for checking the validity of marks is very weak. Second marking, for example, is virtually non-existent and although some universities discourage oral examinations to reduce the possibility of informal payments, it is often not fully enforced. Frequently there is no, or little, moderation of module marks and a system of external examiners to moderate marks is not used. It would appear, although caution is taken when making this statement, that paying to pass exams is less prevalent in more prestigious universities, potentially because of the relatively higher salaries paid to staff.

In Ukraine an independent external assessment (IEA) scheme was recently introduced in an attempt to remove the entry process from universities, but this has also become mired in complaints about corruption. However, as is usual with corrupt practices, new ways to circumnavigate anti-corruption legislation were quickly found. For example, names were added to lists and entrants were given the status of winners of school competitions (who are exempt from the entrance exams) to ensure their entrance. Several loopholes therefore still remain in the entrance process, allowing corrupt practices to remain or to flourish. Notably, in the first couple of years after the IEA’s introduction there were reports in the media in Ukraine that some of the exam questions had been leaked. More significantly, a small change in the education system, introduced by the minister of education, Tabachnyk, has facilitated new, subtle forms of corrupt practices to develop within the entrance system. While Tabachnyk has kept the external testing system for higher education entrants, a system of school certificates accounting for around 25 per cent of each student’s higher education entrance mark has been re-introduced. Since this re-introduction, numerous reports have appeared in Ukraine’s media highlighting the knock-on effect of corrupt practices in Ukraine’s secondary schools.

Simultaneously, other new varieties of corrupt practices have developed. In the past couple of years increasing numbers have been exploiting small loopholes in Ukraine’s education legislation in which large amounts of benefits are given to children from village schools, disabled children and to others enjoying social privileges. Seemingly, the numbers of such entrants into Ukraine’s HEIs has risen sharply since the introduction of the IEA system, with enterprising families forging medical certificates for their child or transferring their child to a village school before their official graduation. It is not just in the university system, however, that such corruption and informality is found.

Finding employment through connections

There is a small but growing literature on the informal practices employed by organisations in post-Soviet states. This has explored the use of connections to develop businesses (McCarthy et al. 2012), the demand for payments to access free healthcare (Aarva et al. 2009), crony capitalism (Sharafutdinova 2011), the links between big business and the state (Lane 2011) and the extent of organised crime (Holmes 2008). What has been less investigated so far are the informal practices that employers utilise in relation to recruitment and their employees.

To address this lacuna, this section starts by looking at the ‘closed’ nature of Russia’s labour market, concentrating on the graduate labour market (which is much wider than in western European economies), therefore continuing to explore the lived experiences of students as they leave university. Given the type of employment under discussion, we do not here engage in any depth with the processes for positions as manual labourers, where personal connections play a less significant role when finding employment (Walker 2010, 2011). Similar to previous research on entry into the labour market, we will here argue that such entry is relatively closed and that personal connections are key to obtaining decent employment (Demidova and Signorelli 2012; Gerber and Mayorova 2010; Gimpelson et al. 2010; Kapelyushnikov et al. 2012; Vishnevskaya and Kapelyushnikov 2007; Yakubovich 2005). In the following section, we then expand on this body of knowledge by detailing the informal practices that ‘applicants’ without wide-ranging personal connections must endure when trying to obtain employment. Though many might believe that the use of personal connections is not a ‘criminal act’, it can be argued that it goes against labour legislation and at best is demonstrative of the informal nature of the ‘formal’ labour market. As many commentators assert, the form that the Russian labour market model currently takes is a mixture of very inflexible formal legislation and the informal practices that are employed to get around them (Gimpelson et al. 2010; Kapelyushnikov 2011; Kapelyushnikov et al. 2012), many of which are fairly easy to label as criminal. The section then concludes by briefly exploring some of the practices employers use to ensure maximum profit from their workforce.

As Gerber and Mayorova (2010: 896) note, ‘The labor market got more personal in the course of Russia’s market transition. The prominence of personal networks as a method of successful job search grew.’ This is a two-way relationship as employers become, according to Mayorova (2008: 9), ‘social capitalists’, taking advantage of their connections to secure employees as well as employees using their networks to obtain work. The use of connections to obtain work is not a new occurrence and nor is it unique to post-Soviet spaces. As the seminal work of Granovetter (1973, 1983) demonstrates, workers in mature economies often draw upon their strong and weak ties when looking for work. However, what is clear is that it is a much more common tactic in transition economies. Clarke (2002: 492) discusses, for example, that in his study of 90 managers in Russia, only one had applied directly for their position, with the rest relying to differing extents on their networks. This, he argues, has led to a ‘closure’ of the Russian labour market as ‘in the past, connections were used primarily as a means of getting a better job. Now it is becoming increasingly necessary to have connections to get any job at all.’

As Mayorova (2008) notes, this enables employers to have greater trust in their employees and for informality to increase as the trust relation means that it is easier to negotiate outside of formal labour regulations. Therefore, an extremely flexible system develops to the advantage of employers (Kapelyushnikov et al. 2012), which is markedly different from central and western European models (Gimpelson et al. 2010). One interviewee, a lawyer in Ukraine, described how his father’s connections ensured his smooth entry into the labour market:

When I left university, I was already assured a job as a lawyer, the profession I had studied in. My father helped me with this. He has a construction company. They build small shopping centres around the city and across the whole of Ukraine. With this he has numerous meetings with lawyers of one company. He asked a favour of the boss … and he agreed. As soon as I completed my diploma, I began to work in the office as a legal junior.

Among interviewees with prestigious formal employment, this story was repeated many times. This is not to say that the interviewees did not deserve the posts they held, or that they are not talented within them, but there is a definite ‘closure’ within such spheres. This perpetuates informal relationships both within and between firms. However, there can be negative outcomes of such relationships when employees are foisted upon them by those who are owed favours or in lieu of making an informal payment to obtain a service or contract. Granovetter’s weak ties are also very much in evidence, especially among lower-income posts. Managers will ask their staff if they can recommend anyone for vacant positions; this saves times as there is no need to advertise or interview widely and it provides an obligation to work hard as they need to repay the trust of the person who recommended them. Thus, it is clear that having a good social network is key to obtaining employment in post-Soviet spaces. While this is not corruption per se, it does lead to a misallocation of resources as it is not necessarily the most suitable person who fill the posts via this method. It also raises levels of informality as often whole negotiations will take place ‘off the record’, thus increasing the chances of informal payments being agreed. Furthermore, and central to the theme of this book, such informal frameworks perpetuate themselves and allow corruption to flourish, and in the instance discussed here sometimes produce positive outcomes, but mostly the end result is far from constructive, especially for those without the connections needed to break into the labour market.

Entering and surviving a ‘closed’ labour market

Many of the interviewees without connections had experienced difficulties above and beyond the usual of identifying and applying for opportunities when trying to obtain full-time employment. These difficulties had involved being asked for bribes to secure a job, dismissal after a very short period of time, the misuse of internships and an overall lack of job security. It is clear from the interviews that there are serious problems across the whole of the post-Soviet labour market, ranging from ‘prestigious’ roles through to the burgeoning service sector. Indeed, given the service sector’s rapid post-Soviet expansion and the higher proportion of women in this sector, a strong dose of gender inequality can be observed, reflecting the patriarchal power structures within these societies. As Turbine and Riach (2012: 182) note, although the state professes gender equality in access to employment, ‘women are still marginalized through the systems, processes and social beliefs that underpin the post-Soviet labour market’. This links back to the point made above that while there are wide-ranging employment laws, the general culture of informality often renders them obsolete.

Furthermore, as Klimova and Ross (2012) note, while labour market participation has risen for women, the inequality in access to ‘good’ jobs has widened. Interviewees discussed how they felt that some of the interviews they had undertaken were exploitative. Many talked about how they had been asked to continue the interview at a restaurant or sauna, with the implications of accepting/declining made very clear. As one said,

After the first interview, which I thought had gone really well, someone from the company called me and suggested that the second interview should take place at a sauna near their offices in the evening. It was clear what he really meant by this. It is so frustrating to be treated in this way when all I am trying to do is get a steady job.

Many also discussed how they had been asked outright to pay a bribe to be given a job. As with the informal payments within the university sector, these payments were not, on average, particularly large, but for the recurrent recipient, when they are combined, it provides a worthwhile tax-free income. While interviewees often refused to make such payments, some discussed how they calculated whether it would be in their long-term interest to make the payment. Sometimes this was proven correct, but in other instances it brought only further problems. It was not uncommon to hear that once the bribe was paid, the worker who had paid it was dismissed soon afterwards. This was more common in the service sector; the following example is not untypical:

After passing the interviews I was told that to get the job I would have to make a large payment to the boss. I went home and thought about this situation and decided to pay the bribe as the job seemed great… . I started work and was really enjoying it when I was abruptly told that my appearance wasn’t right and that I was rude to the customers… . I was upset of course and soon found out that several other women had received similar treatment. We met up and soon realized we had been taken for a ride. We had all paid upfront and then worked for four months, essentially paying off our ‘payment’ before we were dismissed.

By using such processes, enterprises are securing themselves a free labour supply as any salaries that are paid out are covered by the initial informal payment. Similar to this are cases where significant bribes were requested in order for new employees to be provided with tax code numbers or for all of their workplace registrations to be completed. Again, interviewees discussed how they had to make calculations about whether it was worthwhile to make such payments.

Even when entrants managed to gain a foothold in the labour market, the stresses still continue. Although there is extensive employment legislation designed to protect workers, it is in many cases extremely difficult to uphold. As Gimpelson et al. (2009: 24) note, while comprehensive labour legislation was inherited in Russia from the Soviet Union, the weakness of state institutions means that ‘interventions are inefficient and non-random’. The use of the term ‘non-random’ is telling as there is a widespread belief that the courts operate in a way that protects business and those with power and there is little consideration for individual employees. For example, Turbine and Riach (2012) write at length about the prevalence of dismissal due to pregnancy in Russia and the near impossibility of successfully taking guilty parties to court. It is similarly the case in Ukraine. Interviewees virtually unanimously believe that if they had a problem in the workplace, there was no one they could turn to for outside help, arguing that no one would take their problem seriously, and hiring legal assistance is beyond the means of the majority. As one interviewee said:

You know, you work hard, earn some money but your boss is watching over the situation like a wolf. He waits for his moment and pounces. You have no choice, no defence. What was I to do, complain and try and take him to court – there is no official documentation of our ‘agreement’. It is his word against mine. He is a big boss and I am nobody, who do you think the court here will listen to?

Another interviewee discussed how even though he sought legal advice, it was of little use as he was told that it was pointless taking his case to court as the enterprise was able to arrange for a certain judge to hear cases against them and that they always went in their favour.

Given that it is so difficult for those without connections to find work and to maintain it over the initial few months, there are very high levels of anger among this group. The ‘closure’ of the labour market means they are unable to employ their skills and education, they have to move between employment on a regular basis, thus stymieing their career progression, and they have little belief that the situation will improve. Only 30 per cent of the survey respondents were optimistic about the future economic and social development of Ukraine, with the figure falling to 24 per cent among the 16–25-year-old age group. In Russia in 2010, nationwide surveys revealed that only 51 per cent of people were satisfied at work and that 86 per cent had recently become more afraid of losing their employment. Given the difficulties of finding and sustaining work, it is no surprise that large numbers have withdrawn fully from the formal labour market in order to gain more control of their work and to escape the pressures of predatory employers (Roberts 2001).

Often, and with varying degrees of success, they would set themselves up as micro-entrepreneurs, as discussed later, and become involved, for example, in shuttle trading, informal selling and/or cash-in-hand work. This, therefore, is a tactic employed to bypass the strategies of those with power in post-Soviet societies. Given that many of the interviewees had experienced the need to make informal payments to pass through the higher education system, this second negative experience of trying to gain entry to the labour market has significant impacts on their attitudes towards post-Soviet society. As Roberts et al. (2000: 135) state:

Most of the young people we interviewed seemed to feel that they were growing up in times where nothing was stable… . Few believed that they lived in a ‘just world’ where riches normally followed effort and poverty was a fair punishment for sloth… . The young people knew full well, often from bitter personal experience, that, in the short term at any rate, educational backgrounds and qualifications would not count.

This lack of belief legitimises informal work practices as they are seen as a more ‘just’ alternative to the ‘formal’ labour market. Notions of social justice were a common theme in interviews. Many were extremely keen for Ukraine to join the European Union, not for the benefits that this would bring to the country, but because the subsequent freedom of movement would enable them to work in more mature economies without the constant spectre of corruption (for other examples of similar sentiments towards outward migration among young people in post-Soviet contexts, see Dafflon 2009; Mojić 2012; Roberts and Pollock 2011).

Interviewing postgraduate students at a prestigious university in Moscow, whose qualifications should offer relatively easy entry into the labour market, similar feelings were regularly articulated. This is perhaps somewhat surprising, given the opportunities available in Moscow, but again the issue of stability was central:

I have had enough part-time and summer jobs to know that nothing is certain even in big corporations. I know I could get a well paid job here [in Moscow] but even then it is still stressful as you don’t know what is going to happen tomorrow, next week or the month after. Amongst my friends who are already working you hear so many bad stories about their experiences from their bosses. Although you can earn a lot of money in Moscow I want to work in Europe as it would be much less stressful.

Even positions in multinational companies are not seen as particularly ‘safe’, though they potentially provide a path to the international labour market. When asked what they considered the ‘safest’ employment in Russia, the vast majority (80 per cent) replied that positions in public administration would be the most stable as ‘people there look after their own’. These are particularly worrying sentiments as if such highly qualified students wish their future to be elsewhere because of the informality in the Russian labour market, then their abilities will be lost from the nation’s future development (see Dafflon 2009, for a country-wide discussion of this issue). Furthermore, and this is an extremely important point, as informality becomes normalised and institutionalised, then its perpetuation becomes ever more entrenched.

When trust was gained with young interviewees in Ukraine, they were asked if they would take bribes if they were in a position to do so in the future. In the context of their anger and disillusionment with their country’s education and labour market, a majority (55 per cent) said they would do so. They rationalised this in a number of ways. First, they argued that there is a need to ‘earn back’ the investments they have made in their education; second, as work is so insecure there is a need to gain as much income as possible in the shortest time; and third, there is a sense that if it is such a norm then why should they act differently, especially in relation to the actions of the state. In other words, if the state is acting informally, then why should individuals act any differently? Finally, and of great relevance to debates on anti-corruption measures, several participants discussed how, in order to integrate into a workplace, you have to adopt its culture. Therefore, for example, if informal payments are the norm within a workplace and you do not participate, you become the exception and will be viewed with suspicion, leading ultimately to exclusion.

Informality in the formal healthcare system

It is not solely in the realms of education and entry into the graduate labour market, however, that one witnesses the permeation of informality. It is also the case with regard to the healthcare system. With male life expectancy in Russia at just over 60, the lowest in the global North, there has been a great deal of research into the problems surrounding the country’s health and the state of its healthcare system. While the percentage of GDP spent on healthcare in Russia, 5.2 per cent against an EU average of 9 per cent (Popovich et al. 2011), is relatively small, the number of healthcare professionals and hospital beds per capita appears impressive (OECD 2012). However, studies have revealed that there is too high a percentage of low-level trained staff (Rivkin-Fish 2011), issues with adopting the latest approaches and diagnostic methodologies (Rechel et al. 2011), the centralisation of the system and limited access to information (Popovich et al. 2011) and access problems (Fotaki 2009).

There has also been a growing concern that although free access to healthcare is a constitutional right (Popovich et al. 2011), informal payments for supposedly free healthcare are rampant. Many households have to make informal payments in order to see a doctor of their choice, to speed up access or to be referred to specialists (Fotaki 2009). As Kuhlbrandt et al. (2012) note, those receiving medical care constantly worry that they will have to make large payments to receive treatment. This was reinforced in our household survey. Of the 199 respondents entitled to free medicines, 120 (60 per cent) stated that they had encountered difficulties in obtaining them and in many instances had made an informal payment to do so. Only 9 per cent of respondents believed it was easy to obtain ‘free’ healthcare. Popovich et al. (2011: 87) state that in 2009, the latest figures available, 38.5 per cent of the population had ‘paid under the table for treatment while inpatients’ and 28.6 per cent had done similar for outpatient care. Fotaki’s (2009) study found even higher figures, with 80.9 per cent of respondents making informal payments, which can have a dramatic impact on the budgets of lower income households.

It is little surprise, therefore, that many households forego the medicines they need. As one senior citizen asserted:

I need a lot of medicines, but when we don’t have enough money it is very hard to buy them all even though they are meant to be ‘free’. Over the summer it is easier as we sell some products from our dacha but over the winter it is very hard. Sometimes I am in so much pain from my ulcers but I have to chose between buying medicines or having enough food to eat.

Sometimes a lack of money can have more serious consequences. After one focus group in Ukraine, a young woman approached the authors and said she wanted to talk to us in private. As the conversation progressed she became visibly upset and although it was offered to end the conversation, she said she wanted to continue as she ‘wanted people to know what things are like here’:

My father had a heart attack at the dacha. We knew it was too far for the ambulance to come in time so we managed to get him into the car and drove to the nearest hospital. When we arrived mom ran into the hospital to get help and some administrator, or something, came out. He asked us straight out how much money we had to pay for the treatment. We told him we had very little money and he simply replied that they could not help. My dad died in the car park.

While this might seem an extreme example, an interviewee in Moscow discussed how exactly the same thing happened to her father, suggesting that these are not isolated incidents. Furthermore, even when in hospital often informal payments are required for medicines, and family members or friends must provide care. An interviewee in Moscow discussed the treatment of her mother in 2012:

She was in hospital for a broken shoulder but the conditions were so bad she got an infection and almost died. The nurses were very little help and I had to almost live at the hospital. I had to change and wash my mother and clean her bedclothes. We had to take all the food she needed with us and we had to pay for almost all of her medicines.

Similar stories were told to the authors on many occasions (see also Fotaki 2009). Interviewees discussed how they believed giving an informal payment to medical personal would speed up access to treatment and would enable them to see the best doctors. This is important as, with most areas of post-Soviet life, the healthcare system is bureaucratic. One interviewee told of how she had to obtain six stamps on a request for a walking stick, necessitating queuing in six different locations across Moscow. A letter to Argumenty i Fakty newspaper aptly reflected the situation (Kiseleva 2004: 17):

My mother is 95 years old. She is an invalid but she does not have the official documents on disability [needed to claim disability benefits]. She is not strong enough to wait in the numerous queues in the hospital to take the medical tests needed to prove her disability.

As one interviewee noted, ‘one has to be well to be able to obtain disability benefits’.

Conclusions

In sum, this chapter has revealed that despite all of the hyperbole about the hegemony of the formal market economy, just 59.2 per cent of the working-age population is employed in the formal economy. This means that four in every ten people of working age in the post-Soviet world were not participating in the formal economy. Even this, however, is an exaggeration of the reach of formalisation in post-Soviet societies. Many of those who are in formal employment are in jobs infused with informality.

Envelope wages are a popular practice in post-Soviet societies. Some one in eight formal employees receive an envelope wage and this on average amounts to 38 per cent of their wage packet. The result is that even if 59 per cent of the working-age population is engaged in formal employment, some one in eight is in a quasi-formal job. This not only blurs the divide between formal and informal jobs, but also means that the proportion in purely formal employment is even lower than previously assumed. This, however, is not the only way in which the formal economy is infused with informality. As the case studies of kindergartens, schools, the university system, entry into the graduate labour market and healthcare provision reveal, the formal economy in post-Soviet societies remains riddled with crime, informality and corruption. In doing so, this chapter has revealed that it is impossible to view the formal and informal economies as separate and discrete spheres. Informality is an inherent feature of the formal economy in post-Soviet societies.