Introduction

Every society has to produce, distribute and allocate the goods and services required by its citizens. All societies, in consequence, have an economy of some type. Economies, however, can be organised in various ways. To depict how an economy is structured, three modes of delivering goods and services have been commonly differentiated, namely the ‘market’ (private sector), the ‘state’ (public sector) and the ‘community’ (informal or third) sector (Boswell 1990; Giddens 1998; Gough 2000; Polanyi 1944; Powell 1990; Putterman 1990), even if different labels are sometimes attached to these realms, with Polanyi (1944) referring to ‘market exchange’, ‘redistribution’ and ‘reciprocity’, and Giddens (1998) discussing ‘private’, ‘public’ and ‘civil society’. Taking these three modes of delivering goods and services as our starting point, the aim of this chapter is to begin to challenge the widespread consensus which exists regarding the trajectory of economic development in post-Soviet spaces, namely that the transition to the market economy is complete. This discourse relies on two assumptions. First, in all economies it is believed that goods and services are being increasingly produced and delivered through the formal (market and state) sphere rather than through the community or informal sphere (henceforth known as the ‘formalisation’ thesis); and second, that this formal production and delivery of goods and services is increasingly occurring through the market sector, rather than by the public sector (the ‘marketisation’ thesis). In other words, there is a belief that post-Soviet spaces, as Chapter 2 showed, are moving towards the production and delivery of goods and services through the formal economy in general and the formal market economy more particularly.

The intention of this chapter is thus to evaluate empirically this narrative on the direction of post-Soviet economies. It starts by analysing the two meta-narratives about the trajectory of economic development, namely formalisation and marketisation. Then, in order to challenge the widely accepted view that the transition to the market is complete, the following section presents discussion of how this has started to be empirically and theoretically challenged. This sets the scene for the book’s following chapters, which seek to re-read the configuration of the economic and economy in contemporary post-Soviet spaces.

The formalisation thesis asserts that goods and services are increasingly provided through the formal economy (the state and market spheres) and that the informal economy is in demise (for further discussion see Williams 2005a, 2007). Here, the intention is to reveal how this vision of the trajectory of economic development both dominates thought and practice in the post-Soviet world, as Chapter 2 showed, and constrains what is considered feasible and valid as possible futures for post-Soviet spaces. This powerful discourse, however, does not only describe the direction of change, hierarchically ordering countries in the present and informing them of their trajectory (as in the EBRD’s scorecards), but also serves to shape thinking about what action is required by supra-national institutions, national governments, economic development agencies and individuals themselves. For example, the whole thrust of post-Soviet/socialist economic policy, based upon the Washington Consensus, has been focused upon how to facilitate the ‘transition’ to a formal market economy. Grounded in this grand narrative that details what constitutes ‘progress’, governments of post-Soviet/socialist states have tended to concentrate near enough exclusively on developing the formal economy and viewed informal work as, at best, playing a supporting role and, at worst, deleterious to development and something to be formalised so as to allow this trajectory of economic development to be implemented. This is revealed by state discourses on the nature of ‘the informal’ as when the authors discussed the issue with political and economic elites the common answer is that people act in this manner purely ‘to cheat the state out of tax revenues’. There is almost no discussion on how such practices are part of a range of livelihood tactics, that they support and are implicitly interlinked with the formal or how they are created in response to the forms of capitalism that have developed in these countries.

As noted in the previous chapter, the reforms enacted in the post-Soviet world were aimed at creating an economy that only exists in textbooks. However, as Carrier and Miller (1998: 225) discuss, this was of little importance to those leading the reforms as ‘economic models are no longer measured against the world they seek to describe, but instead the world is measured against them, found wanting and made to conform’. Arguing that we now live in a time of economic virtualism (for example, economic models and/or the Washington Consensus), Carrier (1998: 8) argues that there was a

conscious attempt to make the real world conform to the virtual image, justified by the claim that the failure of the real to conform to the idea is a consequence not merely of imperfections, but is a failure that itself has undesirable consequences.

In this so-called ‘virtualism’, the formal economy in the formalisation thesis represents progress, modernity and advancement, while the informal economy is indicative of backwardness, under-development and traditionalism (Peck 2010). Through this, Wacquant (2012: 66) sees ‘neoliberalism as an articulation of state, market and citizenship that harnesses the first to impose the stamp of the second onto the third’. In other words, it is more than an economic approach and one which attempts to destroy anything that is outside of its realm, i.e. the informal.

As such, the formalisation thesis depicts the formal and informal economy as what Derrida (1967) calls a ‘binary hierarchy’. For him, western thought is dominated by a hierarchical binary mode of thinking that, first, conceptualises objects/identities as stable, bounded and constituted via negation, and second, reads the resultant binary structures in a hierarchical manner where the first term in any dualistic opposite (the superordinate) is endowed with positivity and the second term, the subordinate (or subservient) ‘other’, with negativity. Read through this lens, the depiction of the formal and informal economy in the formalisation thesis is one in which the informal economy represents the subordinate ‘other’ endowed with negativity, while the formal economy is read as a superordinate and is attributed with positivity (see also Routh 2011). As McFarlane and Waibel (2012: 5) state, the formal is normally seen as ‘rule based, structured, explicit … and regular’.

Indeed, to see how the informal economy is read in this dominant narrative as a subservient ‘other’ endowed with negativity, whose meaning is established solely in relation to its superordinate opposite (the formal economy), one needs look no further than the numerous adjectives to denote this sphere. As Latouche (1993: 129) recognises, ‘most of them simply qualify – either directly or indirectly – whatever is meant, in a negative way’ (see also Cooper and May 2012). Variously referred to as ‘non-structured’, ‘unpaid’, ‘non-official’, ‘non-organised’, ‘a-normal’, ‘hidden’, ‘a-legal’, ‘black’, ‘submerged’, ‘non-visible’, ‘shadow’, ‘a-typical’ or ‘irregular’, this sphere is thus denoted as ‘bereft of its own logic or identity other than can be indicated by this displacement away from, or even effacement of, the “normal”’ (Latouche 1993: 129). It is described by what it is not – what is absent from, or insufficient about, such work – relative to the formal sphere, and this absence or insufficiency is always viewed as a negative feature of such work (for further discussion on the terminology of informal work and its negative reading see Webb et al. 2012). Overall, as Lemaitre and Helmsing (2012: 747) note, the ‘non-market’ is most often discussed in reference to ‘market failures’.

It is not simply the adjectives used to denote this sphere, however, that display how the formal/informal economy is represented as a binary hierarchy. The narrative of what constitutes progress in the formalisation thesis similarly privileges the superordinate over the subordinate other. The informal sector is read as primitive or traditional, stagnant, marginal, residual, weak, and about to be extinguished; a leftover of pre-capitalist formations that the inexorable and inevitable march of formalisation will eradicate. As McFarlane and Waibel (2012) discuss, moreover, there is also often assumed to be a spatial hierarchy, with informal areas such as the ‘slum’ seen as totally separate from formal spaces such as the ‘market’. Indeed, a universal natural and inevitable shift towards the formalisation of goods and services provision is envisaged as post-Soviet societies become more ‘advanced’. The persistence of supposedly traditional informal activities, therefore, is taken as a manifestation of ‘backwardness’ (e.g. Geertz 1963) and it is assumed that such work will disappear with economic ‘progress’ (Lewis 1959). As the rest of the book shows, these prognoses have simply not come to pass. However, the informal is still often seen as a ‘means of refuge’ for those unable to succeed in the formal economy. Venkatesh’s (2006: 385) extremely interesting work on informal practices in disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Chicago highlights its positive elements, but still portrays it as a binary which cannot be bridged, when he says:

The underground economy enables poor communities to survive but can lead to alienation from the wider world… . On the one hand, the underground economy is a space forged by exclusion from the social mainstream. Much of the reason for lending to one another, hiring off the books, and solving crimes without the aid of the police is that banks discriminate against the poor, mainstream employers and unions do not do effective out-reach to the poor and minorities, and law enforcement does not provide adequate service to the inner city. On the other hand, however meaningful and satisfactory it may be for those involved, this kind of adjustment does little over time to bring about improvement in credit availability, labor force participation, and policing. It does little to leverage more stable and productive relationships with the institutions of the wider world.

Informal work is thus read as existing in the interstices, or as scattered and fragmented across the economic landscape (Günther and Launov 2012). Formal work, by contrast, is still represented as systematic, naturally expansive and coextensive with the national or world economy (White and Williams 2012).

Such a hierarchical and temporal sequencing of formal and informal work in the formalisation thesis, therefore, focuses upon the imminent destruction of the informal economy, its proto-capitalist qualities, its weak and its determined position, viewing it either as ‘the mere vestige of a disappearing past [or as] transitory or provisional’ (Latouche 1993: 49). Rarely is the informal sector represented as resilient, ubiquitous, capable of generative growth, or as driving economic change in the formalisation thesis. Nor is it represented as part of a multitude of different forms of work co-existing in the contemporary world but instead is always positioned in a temporal sequence where the informal sphere is characterised as a remnant of the past and ‘backward’, while the formal sphere is characterised as ‘modern’ and ‘progressive’. There is also almost no discussion on the symbiotic relationships between the two spheres – for example, on how informal practices enable households to perform their formal work, or the role that informal labour plays in global production chains (Phillips 2011). Rather, the informal sphere is near enough always viewed as possessing wholly negative attributes while the ‘progressive’ formal sphere is assumed to possess positive features. For example, Bayat (2007: 579) argues that ‘informal life’, as typified by ‘flexibility, pragmatism, negotiation, as well as constant struggle for survival and self-development’ is the ‘habitus of the dispossessed’. Through this the spaces which the informal processes themselves take place in can be cast in a negative fashion with a need to reclaim them for ‘the formal’. As Roy (2011: 233) describes:

The valorization of elite informalities and the criminalization of subaltern informalities produce an uneven urban geography of spatial value. This in turn fuels frontiers of urban development and expansion. Informalized spaces are reclaimed through urban renewal, while formalized spaces accrue value through state-authorized legitimacy. As a concept, urban informality therefore cannot be understood in ontological or topological terms. Instead, it is a heuristic device that uncovers the ever-shifting urban relationship between the legal and illegal, legitimate and illegitimate, authorized and unauthorized.

Many political economists, recognising that the informal sector is persistent and growing, have portrayed it as a new form of work emerging in late capitalism as a direct result of the advent of a deregulated, open world economy, which is encouraging a race-to-the-bottom. In this reading, informal workers are viewed as sharing the same characteristics subsumed under the heading of ‘downgraded labour’: they receive few benefits, low wages and have poor working conditions (Field 2012; Routh 2011). In sum, the depiction is of the informal sphere as a pre-modern sector composed of workers engaged in exploitative and oppressive work, and thus a hindrance to ‘progress’. This is encapsulated in the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) campaign to reduce informal work which, as Lerche (2012) discusses, is dubbed the ‘decent work approach’. Obviously this implies that informal work is ‘indecent’ (this is not a criticism of the campaign per se, or to suggest that exploitation does not take place, but rather a reflection on how such work is labelled and categorised). Seldom are positive attributes assigned to the informal sphere, such as how this work is autonomous and often rewarding in nature for its participants and the role it plays in general economic development (see Philips 2011).

One notable exception is, however, put forward by Sassen (2009: 30) who, similar to Standing (2011), argues that globalisation has led to an increase in informalisation. She argues that this is not just confined to the global South or to the margins of big cities, but is integral to all global cities. Casting informal modes of production as a means of creative freedom, she discusses how an

often overlooked trend has been the proliferation of an informal economy of creative professionals in these cities. Comprised of artists, architects, designers, and software developers, this new informal economy greatly expands opportunities and networking potentials for people to operate in the interstices of urban and organizational spaces that are usually dominated by large corporate actors. It also allows these artists and professionals to escape the corporatization of creative work. In this process they contribute a very specific feature of the new urban economy: its innovativeness and a certain type of frontier spirit.

This far more nuanced approach begins to reveal the relationships between the formal and informal as much more than a binary hierarchy. However, such arguments are rare within academic debates, especially within economics and management (see Godfrey 2011, for further discussion on how the informal is a ‘new’ space for research), and even more so within policy discussion and construction. The outcome in post-Soviet spaces and beyond is that the dominance of the formalisation thesis results in the possibilities for the trajectory of economic development to be closed off from anything other than formalisation. In other words it is argued that there is only one future for economic development and it is one in which there is a linear path towards a formalisation of work.

Yet despite the widespread acceptance of this thesis and its normative propositions, little evidence is ever brought to the fore to corroborate that this is indeed the direction of change and that formal work possesses positive attributes and informal work negative features. Instead, it is simply assumed that this is the case. Given that other ideas in the social sciences are seldom, if ever, accepted without evidence, there is a real need for a rigorous investigation of this thesis, especially when it is recognised that it not only seeks to reflect lived practice but also acts as a narrative that is being used to shape the direction of economic development. This will be returned to below. First, however, the fact that it is a particular type of formal economy that is widely seen to be coming to the fore needs to be discussed.

The marketisation thesis

It is not only the narrative of an ongoing formalisation of work whereby goods and services are increasingly produced and delivered through the formal (market and state) sphere rather than using informal work that has dominated thought regarding the direction of post-Soviet economies. It is a particular type of formalisation that is seen to be occurring. The widely held view is that the formal production and delivery of goods and services is increasingly occurring through the market sector (rather than by the public sector). This is here termed the marketisation thesis, but might also be termed the ‘commercialisation’ or ‘commodification’ thesis.

At the present moment in history, the near-universal belief is that of the three modes of delivering goods and services, the market is expanding while the other two spheres are contracting (e.g. Lee 2000; Polanyi 1944; Scott 2001; Smith 2000; Watts 1999). Indeed, so dominant is this narrative that few can imagine a future for post-Soviet spaces other than the further encroachment of the market. This, therefore, severely curtails what is considered feasible, valid and possible regarding the direction of economic development. As Flavin et al. (2011: 252) state:

The study of the market economy is as old as social science itself. This is hardly surprising given that since the emergence of capitalism, market principles have come to structure economic production and exchange, and thereby to permeate the wider social order through that structuring. Whatever their ultimate judgment on capitalism, from advocates (such as Adam Smith or Milton Friedman) to opponents (e.g. Marx or Bourdieu) to those who are both (say, J. S. Mill or even John Rawls), social theorists widely agree that once introduced, the market ultimately comes to influence the entire social order.

How, therefore, does the marketisation thesis view the trajectory so far as the production and delivery of goods and services is concerned? Breaking this thesis down into its component parts, first, the belief is that goods and services are increasingly produced for exchange; second, these exchanges are seen to increasingly take place on a monetised basis; and third and finally, this monetised exchange is viewed as increasingly occurring for the purpose of profit. For adherents to the marketisation thesis, therefore, profit-motivated monetised exchange is seen to be expanding into new spheres of everyday life while non-market economic practices (i.e. the public and informal spheres) are contracting. As Crouch (2012: 366–337) argues:

In recent decades objections to political attempts to impose a moral framework on economic life have become increasingly triumphant, as neoliberal ideas about the superiority of markets and corporations over government action have become dominant. The same ideology has also encouraged us to bring more and more areas of life within the compass of this economic reasoning. Fields like health and education, which in the past were seen as having their own sets of values, have been brought into the market.

As he goes on to suggest, as profit maximisation is ‘the sole goal of corporations’ it became seen that ‘no other institutions in society should try to establish alternative goals’. This notion of the impending hegemony of marketisation has been asserted to be happening in many realms (Wacquant 2012), including education (Natale and Doran 2012; Newman and Jahdi 2009; Tilak 2009) and healthcare (Burau 2012; Jensen 2011; Sturgeon 2010). As Eikenberry (2009: 592) notes, marketisation now even ‘pervades thinking and practice in non-profit and voluntary organisations today’; Ciscel and Heath (2001: 401) argue that capitalism is transforming ‘every human interaction into a transient market exchange’; and Jessop (2012) discusses how this narrative is interwoven within uncritical discourses of globalisation. Within this framework Harvey (2011: vi) states that capital is seen as ‘the lifeblood that flows through the body politic of all of those societies that we call capitalistic, spreading out, sometimes as a trickle and other times as a flood, into every nook and cranny of the inhabited world’. As Dicken (2003: 579–580) puts it in the context of the command economy’s collapse and China’s economic reforms:

More than at any time in the past 50 years, virtually the entire world economy is now a market economy. The collapse of the state socialist systems at the end of the 1980s and their headlong rush to embrace the market, together with the more controlled opening-up of the Chinese economy since 1979, has created a very different global system from that which emerged after World War II. Virtually all parts of the world are now, to a greater or lesser extent, connected into an increasingly integrated system in which the parameters of the market dominate.

The outcome, in the eyes of a leading neo-liberal economist, is that ‘Capitalism stands alone as the only feasible way rationally to organize a modern economy’ (De Soto 2001: 1), and this leads him to assert that ‘all plausible alternatives to capitalism have now evaporated’ (De Soto 2001: 13). It is not just neo-liberals, however, who view this to be the case, and there is much criticism of the ‘hegemonic left-liberalism’ which, it is argued, uncritically adopts ‘the mantra that there is no alternative to the capitalist market’ (Cremin 2012: 46). As Hickel and Khan (2012: 205) forcefully argue:

As a result, neoliberal ideology has become a totalizing way of life, a world-view that furnishes the terms for everyday praxis and representation, creates its own forms of political participation and activism, and promotes a virtually unassailable notion of morality. It is not just a manipulative ploy to appropriate surplus value, but a regime in the truest sense of the term—a cultural logic that insinuates itself into every aspect of lived experience. Neoliberal logic cuts across class divides, religious and cultural affiliations, and political loyalties. It is articulated not only on the trading floors of the New York Stock Exchange, not only in university economics departments, not only in the marble halls of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), but also—crucially—in the politics of progressive institutions like the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), by the fashionable environmentalists doing the rounds in American universities, by gender and racial justice advocacy groups, and by charitable philanthropists of all stripes [emphasis added].

Thus, for adherents to the narrative of marketisation, one mode of exchange is replacing all others. The formal market economy is becoming the economic institution rather than one mode of producing and delivering goods and services among many. The notion that the formal market economy is expanding and all other realms shrinking has today taken on the aura of an uncontested fact, with the only debate being the pace, extent and unevenness of marketisation. For some, the process is rather more complete and the formal market economy more hegemonic than for others. Comeliau (2000: 45), for example, talks of ‘its almost exclusive use to solve the great majority of economic and social problems’ while Thrift and Walling (2000: 96) asserts that ‘What is certain is that the process of commodification has reached into every nook and cranny of modern life’. For others, however, there is still seen to be some distance to travel before the total marketisation of working life is absolute (Gough 2000; Watts 1999). As Watts (1999: 312) puts it,

The process by which everything becomes a commodity – and therefore everything comes to acquire a price and a monetary form (commoditization/commodification) – is not complete, even in our own societies where transactions still occur outside of the marketplace. But the reality of capitalism is that ever more of social life is mediated through and by the market.

Among such commentators, therefore, there is no questioning of marketisation. The only debate is over the extent to which it has so far colonised the production and delivery of goods and services and the distance that needs to be travelled before the process is complete. Despite the predominance of this narrative, scholars rarely offer more than some broad-brush qualitative judgement. None attempt to measure, even in the crudest terms, the extent or pace of its encroachment or even its unevenness. As Harvey (2000: 68) posits with regard to what he considers a highly uneven process,

if there is any real qualitative trend it is towards the reassertion of early nineteenth-century capitalist values coupled with a twenty-first century penchant for pulling everyone (and everything that can be exchanged) into the orbit of capital while rendering large segments of the world’s population permanently redundant in relation to the basic dynamics of capital accumulation.

Indeed, this is the consensus. Even if the formal market economy is forever stretching outward to pull in more spheres of life and colonise areas previously untouched by its hand, this is widely regarded as a highly uneven process. Few, however, doubt that the overarching global trajectory is towards the hegemony of the formal market economy. Nor is there much difference between right-and left-wing political discourses. Both sides of the political spectrum concur that the overarching process is towards the dominance of the formal market economy, even if their reasons for asserting this and normative views on its consequences vary considerably. As Cremin (2012) notes, this even extends into discussions which should be especially critical of the discourse, such as debates on environmental issues and social justice. For a brief moment in time at the credit crunch’s apogee, it appeared that there might be space for discussion on alternative pathways for ‘the economy’. With people protesting on the streets against the return of Washington Consensus-style approaches in the majority of countries in the global North, debate seemed inevitable. However, the moment was fleeting and as Jessop (2011: 17) states:

Much mainstream commentary has read the crisis from the viewpoints of capital accumulation rather than social reproduction, the global North rather than the global South, and the best way for states to restore rather than constrain the dominance of market forces.

Therefore, market solutions to market problems magically appeared to be the only way out of the crisis and for future development. However, besides the aforementioned discussions on the pace, extent and unevenness of the process of commodification, such protests and debate highlight that there are contrasting normative positions about, first, whether marketisation is to be celebrated or not, and second and often inextricably inter-related, whether it is a ‘natural’ and ‘organic’ or a ‘socially constructed’ process. Each issue is here considered in turn.

Towards a formal market economy: positive or negative?

Different stances exist on whether this turn towards the formal market economy is to be celebrated or not. At one end of the spectrum are those neo-liberals for whom marketisation is positive because it results in liberation, freedom and progress from the irrational constraints of tradition and collective bonds, creating a social order from the market-coordinated actions of free and rational individuals. This advocacy of marketisation is often inextricably tied to a view of market-oriented behaviour as the natural basis for all social life. Depicted for instance in Thatcherism, a cultural and political revolution is seen to be required to remove from social life anything that might reduce the centrality of market models as the basis of social order.

As Block (2002) points out, this celebratory view of capitalism in neo-liberal thought has taken on board many of the tenets of what originally was a critical Marxian discourse. On the one hand, the very term ‘capitalism’, that until the late 1960s was unused in polite company, has now been adopted by neo-liberals in a much more positive sense to convey the type of society being sought. On the other hand, the core Marxist idea that economic organisation sets the basic frame for the larger society, previously considered objectionable and rejected as ‘vulgar materialism’, is now widely accepted by neo-liberals. The result is that today capitalism is the name the business media uses and the idea that the structure of the economy determines the wider society has been transformed from ‘vulgar materialism’ to common sense. More importantly, the fundamentally Marxian claim that capitalism as an economic system is global, unified and coherent was embraced by Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan and other apostles of neo-liberal ideology in order to encourage their goals of privatisation, deregulation and public sector retrenchment. In an increasingly global capitalist economy, it was asserted that countries had no choice but to follow such a path.

For many on the left of the political spectrum, meanwhile, marketisation is again accepted, but this process is seen more negatively. For them, the increasing penetration of the formal market economy is highlighted, but so as to display how it leads to an eroding of communal life and has deleterious consequences for social values that might stand above the merely economic measure of price (e.g. Comelieau 2002; Slater and Tonkiss 2001). As Comelieau (2002: 45) states,

wherever market rationality acquires dominance, it transforms social relations in their entirety. Resting as it does upon private appropriation and competition, it entails individualist rivalry far more than mutual support as the basis for relations among the members of a society. It thus has a destructive impact upon the ‘social fabric’ itself.

This highlighting of the deleterious impacts of commodification, of course, is by no means new. Indeed, Beveridge (1948: 322), widely recognised as the founder of the modern welfare state, was seriously concerned about the emergence of what he called the ‘business motive’. For him, there was a need to hold onto ‘something other than the pursuit of gain as the dominant force in society. The business motive … is … in continual or repeated conflict with the Philanthropic Motive, and has too often been successful.’ He concludes that ‘the business motive is a good servant but a bad master, and a society which gives itself up to the dominance of the business motive is a bad society’. The negative view of marketisation therefore depicts the implementation of an implacable logic of quantification and formal rationality as producing inequality, social disorder, loss of substantive values and a destruction of both individual and social relations. As Carroll (2010) argues, this even extends into development programmes to the global South which, wrapped up in the guise of the post-Washington Consensus, amount to little more, he argues, than ‘deep marketisation’ rather than pathways to social justice.

The formal market economy: natural or constructed?

Directly related to this debate on the virtues of the formal market economy is a discussion concerning whether such a trajectory of economies is ‘natural’ and ‘organic’, or ‘socially created’. For neo-liberals, marketisation is commonly viewed as a natural or organic process, while for those critical of the consequences it is more commonly viewed as socially constructed. Before analysing these contrasting positions, however, it is necessary to reiterate the shared ‘buying into’ the meta-narrative of marketisation by both bodies of thought. As Slater and Tonkiss (2001: 3–4) assert, ‘political and economic orthodoxies treat markets as self-evident, permanent and incontestable’. In the ‘natural’ or ‘organic’ view, this trajectory towards capitalist hegemony is portrayed as inevitable, all-powerful and all-conquering, even an unstoppable supernatural force.

Indeed, this force of nature is even sometimes assigned human characteristics and emotions. In the business media, for example, markets are often depicted as calm, depressed, expectant, hesitant, nervous and sensitive. Sometimes the pound sterling, euro or US dollar has a good day, at other times it is ailing or sinking fast. Markets seem, therefore, to be ascribed with human attributes beyond the control of mortals. They are superhuman god-like figures. This is more than simply a discourse to make them comprehensible to the public by financial journalists. It is imbuing markets with the force of nature, giving them a divine will. The outcome is that ‘there is no alternative’ but to obey the logic of this all-powerful force. Seen in this manner, capitalism is constructed as existing outside of society or even above it. Reflecting the stance of many economists and formal anthropologists, the economy becomes a separate differentiated sphere. Instead of economic life being part of broader social relations, these relations become an epi-phenomena of the market; there is an economisation of culture. For those more critical of marketisation, however, this ‘un-embedded’ organic view of capitalism is rejected. For them, the formal market economy is socially constructed and although the momentum is towards an ever more marketised world, this does not mean it cannot be stopped. Following Polanyi (1944: 140), it has been widely recognised that ‘the road to the free market was opened and kept open by an enormous increase in continuous, centrally organized, and controlled interventionism’ and as such, that the formal market economy is a created system rather than a natural or organic one.

One way in which this view of the formal market economy as a created system has come to the fore, albeit implicitly, is in the literature on the ‘varieties of capitalism’ (Coates 2002; Thelen 2012; Whitley 2002) that has developed into discussions on variegated capitalisms (Bruff and Horn 2012; Dixon 2011; Jessop 2012). The contention that different varieties of capitalism developed in Anglo-Saxon countries, within the EU and East Asia for example, displays that there is no one single variety with one uniform logic, but a multiplicity of strains reflecting the different social systems in which they are created. The key problem with this varieties-of-capitalism literature, however, is that it has been largely silent on the critical issue of capitalism as a natural system (Bruff and Horn 2012). Although implicit is the idea that there is no single unified system that operates like a force of nature, it is seldom explicit. The outcome is the persistence of a view that capitalism is some natural or organic system beyond the control of the societies in which it exists. Nevertheless, even when portrayed as created rather than organic, the validity of the inevitable drift towards the formal market economy is still not widely questioned. A marketisation of economic life is still seen to be taking place. Although in principle, social constructionists need not argue this since they recognise that marketisation is not inevitable, in practice, few do so. To transcend the marketisation thesis, in consequence, it is necessary to highlight more explicitly the lack of evidence to support this meta-narrative concerning the direction of economic development.

The formal market economy: a delusion?

Given the widespread assumption that capitalism is penetrating ever more deeply into post-Soviet spaces, one might think that there would be voluminous evidence supporting this view of the trajectory of economic development. Yet a worrying and disturbing finding once one starts searching for the evidence is that hardly any is ever provided. For example, pronouncements by authors such as Rifkin (2000: 3) that ‘The marketplace is a pervasive force in our lives’, and from Gudeman (2001: 144) that ‘markets are subsuming greater portions of everyday life’ are offered to the reader with no supporting evidence. Similarly, the assertion by Carruthers and Babb (2000: 4) that there has been ‘the near-complete penetration of market relations into our modern economic lives’ is justified by nothing more than the statement that ‘markets enter our lives today in many ways “too numerous to be mentioned”’ and the spurious notion that the spread of marketised ‘ways of viewing’ signals how marketisation is becoming hegemonic. Watts (1999: 312), in the same vein, supports his belief that although ‘commodification is not complete … the reality of capitalism is that ever more of social life is mediated through and by the market’, merely by pointing out how subsistence economies are rare.

Such thin evidence is by no means exceptional. Few commentators move beyond what Martin and Sunley (2001: 152), in another context, term ‘vague theory and thin empirics’. Perhaps because it is a widely accepted canon of wisdom, evidence is seldom deemed necessary. Indeed, perhaps the growing hegemony of the formal market economy is so obvious to all that there is no need to provide evidence. Perhaps, however, it is not. No other ideas in the social sciences are accepted without corroboration and there are no grounds for exempting the formalisation and marketisation theses. Perhaps the only reason for exempting them is if one believes they are irrefutable facts. If so, then interrogating that this is indeed the case should be welcomed, especially given the paucity of evidence so far provided.

Why, therefore, is evidence not sought? One principal reason is perhaps that a ‘way of viewing’ has become confused with a lived reality. To take an example, recent years have seen the advent of discussions of a ‘marriage market’ whereby people seek out and take decisions on partners much like any other profit-oriented investment. Yet just because this endeavour can be read in a formal marketised manner does not mean that this endeavour is now marketised; just because one can read marriage and partnership as a formal market transaction does not mean that everybody is doing so, marrying and choosing partners for profit-motivated purposes. Just because the language of the formal market realm is now colonising more and more areas of human existence, reaching far into inviolable sanctuaries, such that we can now talk of emotional investments, erotic capital and of the returns on our relationships, does not mean that this is now always the lived practice. Making a friendship might pay dividends, be profitless, rewarding, cost us dear, we may shop around for new friendships, be in the market for a new relationship, have the assets of our youth, intellect or energy so that we can make capital out of them, there may be pay-offs, bonuses to be had and meagre returns from friendships, and we may all have our price, but this language does not mean that there is a marketisation of everything.

Indeed, even if this marketised ‘way of viewing’ has become more common, commentators must know that this does not necessarily translate into lived practice. They live in post-Soviet societies and understand the social mores that prevail. They must know that seeking monetary profit in all social transactions is widely deemed unacceptable and inappropriate. Even if one acts in a market-like manner in commercial transactions, the same cannot apply to exchanges between friends and kin where reciprocity, altruism and charity should and must prevail. Different exchange relations are appropriate and acceptable in different social situations. Doing a favour for kin, friends or neighbours is very different to selling a service to a client, and disputes over whether something is a favour or a service is a dispute over whether the relationship is friendship or commerce. Just because an altruistic favour can be read as market-like and profit-motivated does not make it so.

Moreover, such commentators must know that there are well-defined socially constructed boundaries it is unacceptable to cross, or what Block (2002) calls ‘blockages to commodification’. Domains can be identified where, although money may not be completely excluded, its use is often highly constrained, as in the example of exchanging gifts. Although the giving of gifts is a universal trait, its pattern and meaning varies cross-culturally (Bloch and Parry 1989). In many post-Soviet societies, gift exchange tends to be personal and altruistic relative to impersonal and self-interested commodity exchange. As Gregory (1982: 12) states, ‘commodity exchange is an exchange of alienable things between transactors who are in a state of reciprocal independence… . Non-commodity (gift) exchange is an exchange of inalienable things between transactors who are in a state of reciprocal dependence.’ Gift exchange establishes and/or maintains a social relationship between the giver and recipient. A gift invokes an obligation – a relationship of indebtedness, status difference, or even subordination. As such, the meaning of the gift must be appropriate to the relationship. And in contemporary post-Soviet societies, money is seldom seen as an appropriate gift. Furthermore, one would never offer money to somebody who invited you to dinner as a substitute for returning the favour. The debt is personal and direct and must be repaid in kind. Norms of exchange evolve, however, and are not timeless and unchanging. What is inappropriate at one time period or place can become acceptable later or elsewhere.

The point quite simply is that blockages are always present. Although these blockages change over time and space, there are always blockages of one form or another. The argument of exponents of the hegemony of the formal market economy, therefore, can be read as contending that the spheres subject to blocked exchanges are dwindling in number over time as the tentacles of formalisation and marketisation stretch ever deeper and wider. Until now, no evidence has been provided of whether this is the case. The strong consensus, nevertheless, is that the formal market economy is increasingly totalising, hegemonic, all encompassing and universal.

De-centring the formal market economy

Ever since the command economy’s collapse, the recurring narrative, as Chapter 2 showed, has been that the post-Soviet/socialist spaces of East-Central Europe are in transition to a formal market economy, reflecting and reinforcing the broader worldwide process whereby an all-conquering capitalism stretches its wings wider across the globe and penetrates deeper into every crevice of everyday life. The demise of the state as a direct provider of goods and services in favour of the formal market economy, even if the state continues to regulate, albeit in poorer ways and with less developed and appropriate legislation than in western economies (Neef 2002; Sik 1993, 1994; Wallace and Haerpfer 2002), is often taken as evidence. However, such a trend towards privatisation within the formal economy is insufficient to inform an understanding of whether or not a formal market economy is becoming hegemonic. If, for example, the informal economy were growing relative to the formal economy, then the formal market economy would not be becoming increasingly hegemonic.

To question this discourse of marketism that serves the vested interests of capitalism (by constructing the formal market economy as a natural and inevitable future) and closes off discussion of alternative futures for economic development, the degree to which post-Soviet/socialist societies are witnessing the advance of the formal market economy is here evaluated critically. At first glance it might seem like a fruitless exercise to raise doubts about the incursion of the formal market economy into the post-Soviet/socialist world. Here, however, we wish to show that this is far from the case.

To evaluate the validity of this view that the formal market economy is becoming ever more dominant in the post-Soviet/socialist world, on the one hand, it can be indirectly assessed using the proxy measure of formal employment participation rates. If relatively few goods and services were produced, sold and distributed through the formal economy, then few people would be in formal jobs. However, as more goods and services are exchanged in this manner, then a growth in the employment participation rate would be witnessed, culminating in a state of ‘full-employment’. On the other hand, and perhaps more accurately, the extent of formalisation and how this is changing over time can be directly evaluated by comparing the volume and value of formal and informal work in different time periods using measures of either the inputs into, or outputs of, such work. Each measure of formalisation is here evaluated in turn.

A proxy measure: evaluating the shift towards full(er) employment

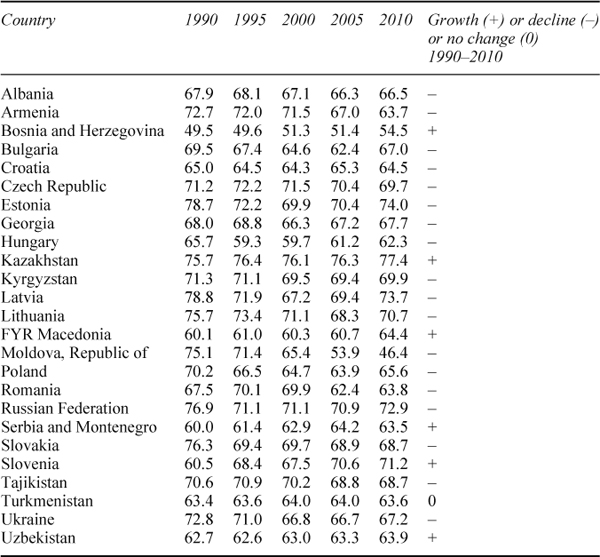

Analysing the degree to which citizens in the post-Soviet/socialist world are immersed in the formal labour market, as stated, is a proxy measure of the degree of formalisation, and evaluating the extent to which they are immersed in formal employment in the private sector is a broad proxy measure of the advent of the formal market economy. Examining solely the employment participation rate of the working-age population (aged 15–64 years old), the ILO (2012) report that in Central and Southeastern Europe (non-EU) and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the employment participation rate was 58.8 per cent in 2000, 57.7 per cent in 2005 and 59.2 per cent in 2010. Four in every ten people of working age in the post-Soviet/socialist world were therefore jobless in 2010. To achieve full participation, two new jobs are required for every three in existence (a 69 per cent increase in the number of jobs). Table 3.1 displays the results for various post-Soviet/socialist countries. This reveals that even if the ‘jobs gap’ is narrower in some nations than others, all are far from a state of full employment. Contrary to the hyperbole and rhetoric of politicians who often assert that full employment is nearly achieved, even Kazakhstan, the country with the highest employment participation rate (77.4 per cent), requires one new job for every three existing jobs in order to achieve full employment.

Source: ILO Key Indicators of the Labour Market (KILM), http://kilm.ilo.org/kilmnet.

Is it the case, nevertheless, that employment participation rates are moving closer to full employment over time? As Table 3.1 displays, this is not the case. Over the past two decades, few nations have managed to close their ‘jobs gap’. Indeed, just five nations in this table made any progress at all. Over this two-decade period, Slovenia managed to raise employment participation rates from 60.5 per cent to 71.2 per cent, Serbia and Montenegro from 60 per cent to 63.5 per cent, Uzbekistan from 62.7 per cent to 63.9 per cent, Kazakhstan from 75.7 per cent to 77.4 per cent and Bosnia and Herzegovina from 49.5 per cent to 54.5 per cent. In most nations, however, the ‘jobs gap’ widened. Some falls were quite dramatic. For example, employment participation rates in the Republic of Moldova fell from 75.1 per cent in 1990 to 46.4 per cent by 2010. The view that there is a long-term universal trend towards fuller employment, therefore, must be treated with considerable caution. It is not borne out by the evidence. Across the post-Soviet/socialist space, in sum, a wide gap exists between current employment levels and a situation of full participation, and the trend is not on the whole narrowing over time in most nations.

Employment participation rates thus provide no evidence of a universal process of formalisation in post-Soviet/socialist economies over the past two decades. However, this is perhaps a very poor proxy indicator. Analysing formal employment alone tells us nothing about whether and how the balance is altering between formal and informal work. For example, increased participation in employment is not always accompanied by a decline in informal work. It may be accompanied by a quicker or slower growth in informal work, a decline in informal work or a similar growth rate, resulting in no change in the overall balance of formal and informal work. Unless both formal and informal work is analysed, therefore, whether there is a process of formalisation will not be known.

More direct measures of the permeation of the formal market economy

To evaluate whether a formalisation of work has taken place in post-Soviet/socialist economies, in theory, one could evaluate the volume and value of the formal and informal spheres in terms of either their inputs or outputs (Goldschmidt-Clermont 1982, 1998, 2000; Gregory and Windebank 2000; Luxton 1997). In practice, it is only data on the volume and value of the inputs that are readily available in the form of time-budget data (Gershuny 2000; Murgatroyd and Neuburger 1997; Robinson and Godbey 1997). Here, participants fill in diaries of what they do, and by analysing the data the time that they spend in formal employment and in other forms of work can be calculated (Gershuny and Jones 1987; Gershuny et al. 1994; Juster and Stafford 1991).

Table 3.2 collates the findings of time-budget studies conducted in some post-socialist societies. This reveals that unpaid work occupies 45.6 per cent of all working time, meaning that the tentacles of the formal economy are far shorter than expounded by proponents of formalisation. Unpaid work, although for so long considered a marginal ‘other’, is in fact larger than paid work, measured in terms of the amount of time spent carrying it out. This, however, should come as no surprise. When Polanyi (1944) depicted well over half a century ago ‘the great transformation’ from a non-market to a market society, he strongly emphasised that this was merely a shift in the balance of economic activity between these spheres. He never suggested it was a total transformation. Even if some have since then portrayed the shift towards a formal market economy as rather more total than Polanyi wanted to portray (e.g. Harvey 1982, 1989), this table demonstrates that Polanyi was quite correct not to over-exaggerate the encroachment of the formal market economy.

Table 3.2 The paid/unpaid work balance in post-socialist economies

| Country | Paid work (minutes) | Unpaid work (minutes) | Percentage of work time spent on unpaid work |

Hungary | 345 | 254 | 42.4 |

Poland | 332 | 244 | 42.4 |

Bulgaria | 285 | 245 | 46.2 |

Czechoslovakia | 320 | 272 | 45.9 |

East Germany | 298 | 276 | 48.1 |

Ex-Yugoslavia | 308 | 292 | 48.7 |

Mean | 314 | 263 | 45.6 |

Source: derived from Gershuny (2000: table 7.1).

It is not only time-budget diaries that provide a direct measure of the degree of penetration of the formal market economy. There are also some very useful direct surveys, including the New Democracies Barometer (NDB) surveys conducted between 1992 and 1998 (Rose and Haerpfer 1992; Wallace and Haerpfer 2002). Given the rather dated evidence provided by these surveys, we here report a survey conducted in eight countries, namely Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia and Ukraine, during 2001 from the Living Conditions, Lifestyles and Health Project funded by the European Union under the INCO-Copernicus programme (see Abbott and Wallace 2009).

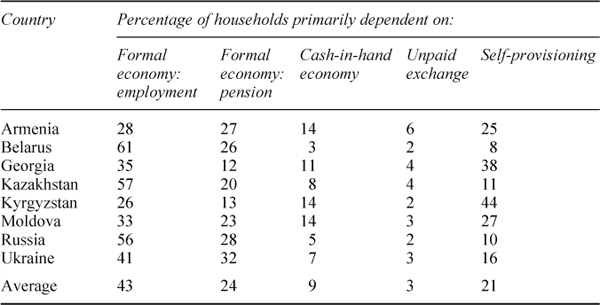

For those who perhaps assume that the formal economy in general and capitalist activity in particular has stretched its tentacles ever wider and deeper, Table 3.3 displays that this is far from the case. First, and examining the main source of income of households, it displays that on average just under half of all households rely on formal employment for their main income, just under one-quarter on pensions, one-fifth rely on non-exchanged work, one-tenth on the cash economy and just over 3 per cent on the social economy. This means that for two-thirds of households the main income is from the formal economy, which includes employment in the public, private and third sectors, and not all of which is therefore formal capitalist endeavour.

Table 3.3 Primary sphere relied on by households to secure their livelihood in CIS countries, 2001

Source: derived from Abbot and Wallace (2009: table 2).

However, there are significant variations between countries. Over 60 per cent of households receive their main source of income from formal employment in Belarus and over half in Kazakhstan and Russia compared with just one-third in Moldova and Georgia and one-fifth in Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. Two groups of countries, therefore, can be distinguished. In the first group, comprising Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine, the vast majority of households (three-quarters or more) received their main income from the formal sector (wages or pensions). In the second group of countries, comprising Armenia, Georgia, Moldova and Kyrgyzstan, there is a much higher reliance on the informal economy, with nearly two-thirds of households’ main income being from the informal economy in Kyrgyzstan and around half in the other three countries.

It might be asserted, of course, that those reliant on the cash-in-hand economy are reliant on capitalist endeavour, albeit of a completely unregulated and illegitimate variety. Recently, however, a growing literature unpacking the motives and work relations underpinning cash-in-hand work has revealed that over half of such work is conducted for friends, neighbours and acquaintances, often for not-for-profit reasons, such as to redistribute money to friends, neighbours and acquaintances in a way that avoids any connotation of charity or to build social support networks (Williams 2004c). As such, households primarily reliant on cash-in-hand work cannot all be assumed to be engaged in capitalist (i.e. profit-motivated monetised exchange) practices, albeit of an illegitimate variety. Although this might be the case for some, this cannot be assumed for all such households. For others, reliance on cash-in-hand work is likely to reflect their overarching dependence on friends, neighbours and kin for their means of livelihood and to be grounded in work relations more akin to mutual aid than profit-motivated capitalist practices.

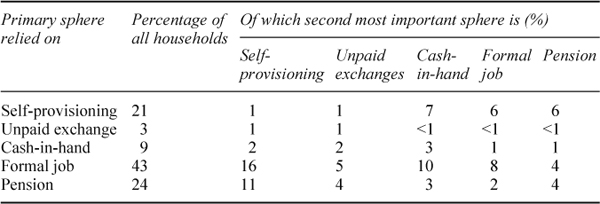

Nevertheless, the important point is perhaps that only for around two-thirds of households in these CIS, formal income sources (employment or pensions) is the primary income source used to secure their livelihood, intimating that the transition to capitalism has been by no means all-encompassing, especially when one considers that some of this dependence on the formal sphere for livelihoods is through employment in the public or not-for-profit sectors or through redistributive state provision (pensions) rather than the profit-motivated capitalist sphere. Even this finding that examines solely the main sources of income, however, perhaps exaggerates the degree to which capitalism has become more central to livelihoods. As Table 3.4 reveals, when households were also asked for the second most important sphere that contributes to their livelihoods, the finding was that just 8 per cent of households cite the formal sphere as being both the first and second most important sphere and just 18 per cent relied on pensions and formal jobs alone for their income. Instead, 64 per cent of households relied on some combination of both formal and informal practices while 18 per cent relied on non-formal sources alone. To refer to these CIS as capitalist societies is thus a grave misnomer. Less than one-fifth of households define themselves as reliant on the formal sphere (which, to repeat, is composed of not only the capitalist sphere but also the public and not-for-profit sectors).

Source: derived from Abbot and Wallace (2009: table 4).

For the vast majority of households, in consequence, a multiplicity of economic practices are used to secure a livelihood, as many smaller-scale qualitative studies have previously displayed in rich detail (Arnstberg and Boren 2003; Burawoy and Verdery 1999; Burrell 2011; Pavlovskaya 2004; Shevchenko 2009; Ghodsee 2011). Indeed, even when the formal sector is cited as being either the principal or second most important contributor to their living standard, it is usually combined with informal economic practices, meaning that a heterogeneous portfolio of work practices is the norm rather than the exception. Indeed, around 90 per cent of households cite sources other than the formal sphere as either most important or second most important to their standard of living. These data thus clearly delineate the limited contribution of the formal sector (i.e. where goods and services are provided through paid employment), never mind the capitalist economy (where this formal provision is conducted by private sector firms for profit-motivated purposes rather than the public or not-for-profit sectors).

Indeed, Table 3.5 further reinforces this shallow permeation of capitalism. It displays that one in four households in these CIS at the time of the survey received no income from the formal economy. Nevertheless, there are some cross-national variations. In a first group of countries (Russia, Belarus and Ukraine), well over three-quarters of households receive income from the formal economy, while in a second group (Armenia, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan) one-third have no connection to the formal economy. Kazakhstan and Moldova, meanwhile, both have just over two-thirds of households receiving income from the formal economy.

Table 3.5 Share of households not receiving income from the formal economy, by country

| Country | Percentage of households receiving income from formal economy | Percentage of households receiving no income from formal economy |

Armenia | 67.2 | 32.9 |

Belarus | 89.6 | 10.4 |

Georgia | 61.1 | 38.9 |

Kazakhstan | 70.8 | 29.2 |

Kyrgyzstan | 56.0 | 44.0 |

Moldova | 72.2 | 27.8 |

Russia | 87.4 | 12.6 |

Ukraine | 82.6 | 17.4 |

Average | 75.1 | 24.9 |

Source: derived from Abbot and Wallace (2009: table 5).

In sum, the majority of households in the CIS do have some connection with the formal economy, but the importance of the formal realm is far from being hegemonic. Instead, the vast majority of households rely principally on a plurality of economic practices to secure their livelihood and capitalist economic practices are just one among many that are employed in order to get by. There are, nevertheless, differences between countries. One group of countries, namely Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan, has a greater reliance on formal modes of production to secure their livelihood than another group that is notably more dependent on other economic practices.

The role of informal economies in post-Soviet societies

Given the shallow and uneven penetration of the formal market economy in post-Soviet/socialist societies, there appears to be a need to rethink the ‘economic’ and ‘economy’ in these spaces. To start to achieve this, the theories behind the role of the informal must be considered, before they are tested empirically throughout the rest of the book. As will be revealed, for many decades a residue thesis was adopted which depicted informal economic activities as leftover and disappearing from view. The recognition of the persistence of informal economic activities, however, has led to the emergence of various competing perspectives that variously seek to explain their role in post-Soviet spaces, namely structuralist, neo-liberal and post-structuralist theorisations which respectively view informal economic activities as a by-product, alternative and complement to the formal market economy. Here, each theorisation is briefly reviewed in turn.

Modernisation theory: the informal sector as a residue

For many decades, the informal sector was depicted as a residue that was gradually disappearing from view, with economic ‘advancement’ and ‘modernisation’ (Geertz 1963; Lewis 1959). This formalisation thesis, therefore, temporally sequences the formal and informal work existing in post-Soviet spaces today. The formal economy is the emergent mode of work organisation and positively depicted as representing ‘progress’, ‘development’, ‘modernity’ and ‘advancement’, while the informal economy is the receding mode of work organisation and negatively portrayed as representing ‘under-development’, ‘traditionalism’ and ‘backwardness’ (Geertz 1963; Lewis 1959).

Here, therefore, informal economic activities are ‘the mere vestige of a disappearing past [or as] transitory or provisional’ (Latouche 1993: 49). Never are they represented as resilient, ubiquitous, capable of generative growth, or as driving economic change. Nor are they even represented as part of a multitude of different forms of work co-existing in the contemporary post-Soviet world, but instead, are always positioned in a historic sequence as a remnant of the past. The outcome is that the trajectory of economic development is closed. There is only one trajectory and it is one in which there is an inevitable, even natural, linear development path towards the formal market economy.

Grounded in this grand narrative of what constitutes ‘progress’, governments of post-Soviet nations have tended to concentrate exclusively on developing the formal economy, and have viewed informal work as, at best, playing a supporting role and, at worst, deleterious to development and something to be formalised. The whole thrust of economic policy is focused upon how to facilitate the ‘transition’ to a formal market economy (Kostera 1995; Parker 2002). The thesis of formalisation is therefore not just a theory seeking to reflect reality, but is what Butler (1990) calls a ‘performative discourse’ that seeks to shape lived practice, or what Hickel and Khan (2012: 205) term ‘a regime in the truest sense of the term’. Yet despite the widespread acceptance of this formalisation thesis, recent years have seen a burgeoning literature contesting this discourse. The major reason is a widespread recognition that the informal economy is not some weak and disappearing realm, but strong, persistent and even growing in the contemporary global economy (ILO 2012; Loayza and Rigolini 2011; Schneider 2012; Williams 2004a, 2004b, 2005a). The outcome is the emergence of various theories which transcend the depiction of informal work as a remnant or residue of the past.

Structuralist theory: the informal economy as a by-product of the formal economy

One such perspective is that which portrays informal economies as expanding rather than dwindling and formal and informal work as inextricably intertwined rather than separate. In this discourse, informal work is growing due to the emergence of a deregulated, open world economy, which is encouraging a race-to-the-bottom in terms of labour standards (Amin et al. 2002; Castells and Portes 1989; Gallin 2001; Hudson 2005; Portes 1994). On the one hand, the growth of informal work, particularly informal waged employment, is seen to be a direct by-product of employers seeking to reduce costs by adopting informal work arrangements. This is reflected in the growth of sub-contracting to not only those employing off-the-books workers under degrading, low-paid and exploitative ‘sweatshop-like’ conditions, exemplified in the garment-manufacturing sector (Bender 2004; Espenshade 2004; Ross 2004), but also those working on a temporary self-employed basis. As Davis (2006: 186) puts it, what we are witnessing in contemporary capitalism is the re-emergence of ‘primitive forms of exploitation that have been given new life by postmodern globalization’.

On the other hand, the growth of the informal economy more broadly defined to include unpaid work also results from the demise of Fordism and socialism (Amin et al. 2002; Hudson 2005). In the new post-Fordist era of flexible production, those of little use to capitalism are no longer maintained as a reserve army of labour and socially reproduced by the formal welfare state, but instead are off-loaded, resulting in their increasing reliance on the informal sphere as a survival strategy. In this reading, the informal sphere is thus extensive in marginalised populations where the formal economy is weak, since its role is to act as a substitute for the formal economy in its absence. It is a work practice undertaken by those involuntarily decanted into this sphere and conducted out of necessity in order to survive (Amin et al. 2002; Castells and Portes 1989).

Unlike the residue thesis where the formal and informal economies are temporally convened, this by-product thesis thus represents the informal economy as a core and integral component of contemporary capitalism. As Fernandez-Kelly (2006: 18) puts it, ‘the informal economy is far from a vestige of earlier stages in economic development. Instead, informality is part and parcel of the processes of modernization.’ Although rejecting the temporal sequencing of the residue thesis, however, the same normative hierarchical reading is maintained. The informal economy is depicted as possessing largely negative attributes and formalisation viewed as the route to progress, albeit more as a prescription of the required socially constructed trajectory of economic development rather than as an organic and immutable view of the direction of change. Exemplifying this by-product approach is the ILO (2012), which recognises that informal work is growing and inextricably intertwined with formal work; its ‘decent work’ campaign prescribes formalisation as the path to progress.

Neo-liberal theory: informal economies as an alternative to the formal economy

For others recognising the prevalence and growth of the informal sector, however, this hierarchical ordering that privileges the formal economy as the path to progress is replaced by a depiction of informalisation as the route to advancement. Akin to the residue discourse, the informal and formal economies are here often seen as separate and discrete, but unlike both the modernisation and structuralists perspectives, participation in informal work is depicted as possessing positive attributes and impacts and is viewed as conducted as a matter of choice rather than due to a lack of choice (Cooper and May 2012; Cross 2000; Gerxhani 2004; Sassen 2009). As Gerxhani (2004: 274) argues, for example, workers ‘choose to participate in the informal economy because they find more autonomy, flexibility and freedom in this sector than in the formal one’. The relationship between informal and formal work is thus read as substitutive, with one seen as a replacement for the other, and the difference between this school and structuralism is that participation in the informal economy is usually depicted as a choice rather than a necessity. For neo-liberals, informal work is not only seen more as a matter of choice than due to a lack of choice, but informal workers are depicted as heroes throwing off the shackles of a burdensome state, and informal work a rational economic path taken to escape over-regulation in the formal realm (Becker 2004; De Soto 1989, 2001; London and Hart 2004; Nwabuzor 2005; Small Business Council 2004). As Nwabuzor (2005: 126) asserts, ‘Informality is a response to burdensome controls, and an attempt to circumvent them’, or as Becker (2004: 10) puts it, ‘informal work arrangements are a rational response by micro-entrepreneurs to over-regulation by government bureaucracies’. For De Soto (1989: 255), in consequence ‘the real problem is not so much informality as formality’.

Informal work, usually depicted as own-account work conducted on a self-employed basis, therefore, is viewed as the people’s ‘spontaneous and creative response to the state’s incapacity to satisfy the basic needs of the impoverished masses’ (De Soto 1989: xiv–xv). It is a rational economic strategy pursued by entrepreneurs whose spirit is stifled by state-imposed institutional constraints and who voluntarily operate in the informal economy to avoid the costs, time and effort of formal registration (Cross and Morales 2007; De Soto 1989, 2001; Perry and Maloney 2007; Small Business Council 2004). Such work is consequently seen as the route to progress and an exemplar of how formal work, as well as the economy more generally, could be organised if it were deregulated. The solution, in consequence, is to liberate the labour market from intervention and the informal economy exemplifies how the formal sphere could be organised if it were deregulated. As Sauvy (1984: 274) explains, such work represents ‘the oil in the wheels, the infinite adjustment mechanism’ in the economy. It is the elastic in the system that allows a snug fit of supply to demand that is the aim of every economy. If left to operate unhampered by the state, then the informal sphere would provide this snug fit. At present, however, this cannot happen because, for example, the state through its formal welfare provision creates a ‘dependency’ culture, preventing populations from taking responsibility for their own livelihoods in the informal sphere. In this approach, in consequence, the informal economy represents a positive alternative to the regulated formal economy.

Post-structuralist theory: the diverse economies perspective

To contest the narrative that nations are universally pursuing a uniform and linear development path towards formal market economies, a corpus of post-development literature has emerged that has begun to re-read the trajectories of economic development of advanced ‘market’ economies (Byrne et al. 2001; Community Economies Collective 2001; Gibson-Graham 1996, 2003; Williams 2004b, 2005a), post-Soviet transition economies (e.g. Round et al. 2008; Smith 2004, 2010; Smith and Stenning 2006) and majority (third-)world countries (e.g. Escobar 1995, 2001; Esteva 1985; Latouche 1993; Sachs 1992). As Smith (2004: 14) succinctly explains, these commentators seek ‘to liberate the non-capitalist from its secondary position in understandings … and to reposition “capitalism”’. Viewing the advocacy of a move towards a formal market economy not as an abstraction seeking to reflect reality but as a performative discourse that is seeking to shape the world by making the reality conform to its image, this post-structuralist or post-development discourse asserts that accepting the thesis of the advent of formal market economies not only serves the vested interests of capitalism (by constructing market hegemony as a natural and inevitable future) but also results in a failure to contemplate the creation of alternatives. The net outcome is that the real world ends up conforming to the image. For post-structuralist commentators, therefore, there is a need to deconstruct the discourse of formalisation and marketisation and articulate alternative representations of the trajectory of economic development, not least by recognising and valuing the existence of economic practices beyond the formal market economy which shine a light on the possibility of constructing alternative futures beyond the hegemony of a formal market economy. As Samers (2005: 876) puts it, they seek to ‘relinquish a vision of a largely unimaginable socialism as capitalism’s opposite, and instead, recover and revalorise a multitude of non-capitalist practices and spaces that disrupt the assumption of a hegemonic capitalism’. In post-Soviet societies in particular, this demonstration that multifarious economic practices persist resonates with the broader transitology approaches of socio-cultural anthropologists (Burawoy and Verdery 1999; Hann 2006; Humphrey 2002).

To challenge the thesis of formal market hegemony, two broad strategies are used. On the one hand, and employing Derridean discourse analysis (Derrida 1967), the informal/formal and market/non-market binary hierarchies are challenged that endow the formal and market economies with positivity and the subordinate informal and non-market realms with negativity. To contest this, two approaches are used. First, attempts are made to revalue the subordinate term, such as by attaching a value to unpaid work (Goldschmidt-Clermond 1982; Luxton 1997). The problem, however, and as Derrida (1967) points out, is that revaluing the subordinate term in a binary hierarchy is difficult since it also tends to be closely associated with the subordinate terms in the other dualisms (e.g. non-market work is associated with reproduction, emotion, subjectivity, women and the non-economic, and market work with production, reason, objectivity, men and the economic). A second strategy is thus to blur the boundaries between the terms, highlighting similarities on both sides of the dualism so as to undermine the solidity and fixity of identity/presence, showing how the excluded other is so embedded within the primary identity that its distinctiveness is ultimately unsustainable. For example, the household is represented as also a site of production – of various goods and services – and the factory also as a place of reproduction (Gibson-Graham 2003). Pursuing either of these strategies can thus challenge the hierarchical binaries that pervade contemporary thought and have until now stifled recognition of the ‘other’ that is non-market work.

On the other hand, and alongside this Derridean approach, some post-structuralist writings follow the path laid by Foucault (1981) by seeking to deconstruct the formalisation and marketisation theses through: first, a critical analysis of the violence and injustices perpetrated by these theories or systems of meaning (what they exclude, prohibit and deny); and second, a genealogical analysis of the processes, continuities and discontinuities by which these discourses came to be formed. Exemplifying this is Escobar (1995), who reveals that prescribing the development pathway of formal market hegemony has violently ‘subjected’ individuals, regions and entire countries to the powers and agencies of the development apparatus. Rather than accept the vision of the ‘good society’ emanating from the west, Escobar’s Foucauldian approach to development discourse opens the way towards ‘unmaking’ the third world by highlighting its constructedness and the possibility of alternative constructions (Escobar 2001). Importantly, his work points the way toward a repositioning of subjects outside a formalisation and marketisation discourse that produces subservience, victim-hood and economic impotence.

Akin to Escobar, Gibson-Graham (1996) has re-read western economic development through a similar post-structuralist lens. For her/them (i.e. they are two authors writing as one), and adopting a similar Foucauldian approach, the use of the degree of formalisation and marketisation as a benchmark for ‘development’ and ‘progress’ and measuring countries against, results in a linear and uni-dimensional trajectory of economic development being imposed that represents non-western nations as backward, traditional, lagging and so forth and positions those western nations at the front with a closed future of ever greater formalisation and marketisation (see also Williams 2002, 2004b, 2005a; Williams and Windebank 2003). This, for them, is a representation of reality and discursive construction that reflects the power, and serves the interests, of capital. By representing the future as a natural and inevitable shift towards the formal market economy, one is engaged in the active constitution of economic possibility, shaping and constraining the actions of economic agents and policy makers.

By re-visioning post-Soviet economies as composed of a diversity of economic practices, the implications are two-fold. First, it suggests that there are other economic practices besides formal market economic practices. Second, by locating work beyond the formal market economy as existing in the here and now, one is engaged in the demonstrable construction and practice of alternatives to formalisation and marketism. This re-reading is thus not simply about bringing minority practices to light. It is about de-centring the formal market economy from its pivotal position in economic development and bringing to the fore the possibility of alternative economic practices and futures beyond the formal market economy. Until now, however, such a post-structuralist approach towards economic development has been seldom applied to post-Soviet spaces. Despite the dominance of the discourse that these so-called ‘transition’ economies are on a natural and inevitable pathway to a formal market economy, numerous small-scale qualitative case studies (as noted above, for example, Burrell 2011; Ghodsee 2011; Pavlovskaya 2004; Shevchenko 2009) have questioned either the dominance of the formal market economy or that the direction of economic development is towards formalisation and marketisation. Here, in consequence, this book further fills this lacuna.

Conclusions: re-figuring the economic in post-Soviet societies

As Chapter 2 showed, the recurring belief has been that post-Soviet economies have witnessed a process of both formalisation and marketisation since the fall of the Soviet bloc and thus that the post-Soviet world has been witnessing a process of transition towards a formal market economy. The outcome has been that one inevitable and immutable future for post-Soviet economies has been envisaged and economic policy has sought to enable this future to come to fruition by near enough entirely concentrating on the development of formal market economies. Indeed, Kostera (1995) has likened the massive intervention and investment to facilitate the emergence of the formal market economy to a religious crusade in which management educators and consultants have acted like missionaries transferring the cult of what Parker (2002) calls ‘market managerialism’ to the heathen masses. Yet as this book will reveal, the post-Soviet world has remained steadfastly grounded in a form of work organisation based on economic pluralism, and there appears to be no sign of this abating in the near future.