4 Beyond the formal–informal economy dualism

Unpacking the diverse economies of post-Soviet societies

Drawing inspiration from the burgeoning corpus of post-structuralist scholars, as discussed in the previous chapter, who have begun to question the narrative of the impending hegemony of the formal market economy in post-Soviet societies and beyond, this chapter seeks to further advance this emergent ‘diverse economies’ literature by constructing an analytical lens for representing the multiple labour practices in economies. Transcending the simplistic formal/informal economy dichotomy, this chapter seeks to conceptualise the multiple kinds of labour that exist in post-Soviet societies by adopting a ‘total social organisation of labour’ approach. As will be shown, this conceptualises a spectrum from formal-oriented to informal-oriented labour practices, which is cross-cut by another spectrum ranging from wholly monetised to wholly non-monetised labour practices. The resultant outcome is to provide an analytical lens for capturing the plurality of labour practices that exist in post-Soviet societies in a manner which shows how they all seamlessly merge into each other.

Having developed this conceptual framework for analysing diverse economies, the second section of this chapter then applies this to understanding the multifarious labour practices used in Ukraine and Russia. Presenting the over-arching results of 600 interviews conducted across various populations in Ukraine and 313 interviews conducted in Moscow, the outcome will be to begin to reveal not only the shallow permeation of the formal market economy in Ukraine and Russia, which have been supposedly undergoing a ‘transition’ to formal market economies, but also the existence of diverse work cultures across different populations along with marked socio-spatial variations in the nature of individual labour practices. This sets the scene for the rest of the book, which unravels the lived experiences of transition in these post-Soviet societies.

Beyond the formal–informal economy dichotomy

To contest the notion of a formal/informal binary hierarchy, a diverse range of critical, post-colonial, post-development, post-structuralist and post-capitalist theorists (e.g. Chakrabarty 2000; Community Economies Collective 2001; Escobar 1995; Gibson-Graham 1996, 2006; Lee 2006; Leyshon et al. 2003; Williams and Round 2007) have begun to blur the boundaries between the two. Following either Butler (1990) by highlighting the performativity of this normative separateness and/or the path laid by Derrida (1967) and Foucault (1977) of discourse analysis and deconstruction, these commentators have sought not so much to invert the normative hierarchy, but rather to highlight the similarities on both sides and to show how the formal and informal are not always composed of entirely different economic relations, values and motives (Chowdhury 2007; Escobar 2001; Gibson-Graham 2006; Gupta 1998; Lee 2006; Pollard et al. 2009; Smith and Stenning 2006; Williams 2005a; Williams and Zelizer 2005).

In consequence, there is now gathering pace a loose body of knowledge that is challenging the long-standing depiction of formal and informal labour as separate and unified spheres, as well as hostile worlds. The most common classificatory schema used in practice to demonstrate the need to recognise the differences and similarities on each side has been to retain a broad distinction between formal and informal labour, but to show how the informal side is not unified by breaking it down into three very different practices, namely: self-provisioning, which is where a household member engages in unpaid work for themselves or another member of their household; unpaid community labour, where a household member engages in unpaid work for somebody who lives outside of the household, and paid informal labour where paid work is conducted that is unregistered by, or hidden from, the state for tax, social security and/or labour law purposes (Leonard 1998; Pahl 1984; Slack 2007; Slack and Jensen 2010; Smith 2010; Smith and Stenning 2006; Wallace and Latcheva 2006; Williams 2005a, 2010a). The problem is that although this classification of labour practices unpacks some of the diversity in informal practices, it leaves intact formal labour as a unified whole and also the notion that the formal and informal are separate spheres composed of distinct economic relations, values and motives. This is similarly the case with other conceptual frameworks and analytical lenses. Gibson-Graham (2006), for example, differentiate transactions into three sub-categories, namely market, alternative market (e.g. off-the-books, barter) and non-market (e.g. gift-giving, subsistence), and also labour practices again into three broad types, namely waged, alternative paid (e.g. cash-in-hand, reciprocal) and unpaid (e.g. family care, self-provisioning). Although these again unpack the informal labour side of the coin, they leave the formal side intact as a unified whole and continue to portray formal and informal as separate distinct spheres.

A total social organisation of labour approach

How, therefore, can the multiple kinds of labour that exist in economies be portrayed more in a manner that shows how the formal and informal are not separate, that the differences within formal and informal-oriented activities are as great as the variations between them, and that the economic relations, values and motives of formally oriented and informally oriented activities are not always different and hostile? Perhaps the most prominent and promising attempt so far is the ‘total social organisation of labour’ (TSOL) approach of Glucksmann (2005: 28), who reads ‘the economy as a “multiplex” combination of modes, rather than as a dualism’. In this approach, and as Taylor (2004) shows, a continuum of labour practices according to their degree of formality is constructed and this continuum is then cross-cut by whether the labour is paid or unpaid (Glucksmann 1995, 2005). This analytical lens of the TSOL was originally used to elucidate the gendered connections between paid and unpaid work and has been widely applied (Acker 2006; Bradley 2007; Crompton 2006; Glucksmann 2000, 2009; McDowell 2005; Pettinger et al. 2005; Strangleman and Warren 2008). Much of the work has so far drawn attention to the ‘multi-modal’ character of contemporary capitalism and how terms like the ‘dual economy’ and the ‘mixed economy’ barely capture the complexity and variety of the forms of provision in existence. This concept, moreover, has been argued to be applicable at micro, meso or macro levels and to units at a range of scales, from the individual and household to a country or global region. One attempt to display this is the work conducted by Lyon and Glucksmann (2008) which compares the contribution of different modes of provision to elder care work in four countries (Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK), revealing how various forms of provision not only have different roles and significance in each country, but also interact in nationally distinctive ways.

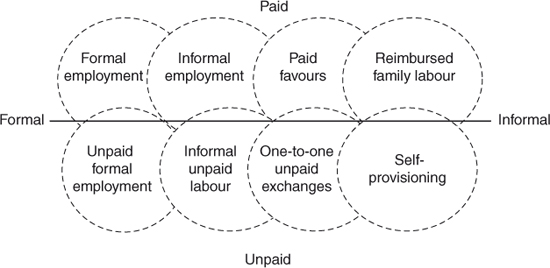

In this chapter the intention is to apply this analytical lens of a TSOL to understanding how labour practices vary across post-Soviet spaces in general, and Russia and Ukraine more particularly. To map this, and as Figure 4.1 displays, a seamless range of labour practices is constructed, ranging first along a spectrum from relatively formal to more informal labour practices, and second, and cross-cutting this, along a further spectrum (rather than dualism) from wholly non-monetised, through gift exchange and in-kind labour, to wholly monetised labour practices. Hatched circles are deliberately used to display how, although various labour practices along these continua can be named, they are in effect part of a borderless continua of practices, rather than separate kinds of labour, which overlap and seamlessly merge into one another as one moves along both the formal/informal spectrum of the x-axis as well as along the monetisation/non-monetisation spectrum of the y-axis. Here, therefore, and unlike previous frameworks, the borderless fluidity between different labour practices is captured and it is clearly shown how the multiple practices are not discrete but seamlessly entwined and conjoined.

The outcome is that eight broad, overlapping labour practices can be identified, each of which possess within them different varieties of labour and which merge at their borders with the other practices. First, there is formal paid labour or formal employment, defined as paid work registered by the state for tax, social security and labour law purposes. Within this formal sphere, three types of formal labour, namely in the private, public and third sectors, have been conventionally distinguished. However, given that private sector organisations are increasingly pursuing a triple bottom line, while public and third sector organisations are also pursuing profit (albeit in order to reinvest so as to achieve wider social and environmental objectives), an ongoing blurring of the boundaries of these three formal spheres is occurring. Paid formal employment as a whole, moreover, is not discrete and separate since it often merges with both unpaid formal employment and informal employment.

Informal employment is here defined as paid labour unregistered by or hidden from the state for tax, social security and labour law purposes (Williams 2009). Different varieties again exist, ranging from wholly undeclared labour where none of the payment is declared for tax, social, security and labour law purposes, to under-declared formal employment where formal employees receive an additional undeclared wage from their formal employer alongside their formal declared wage or the formal self-employed do not declare various portions of their earnings (Williams 2009). Conventionally, however, and adopting a formal–informal economy depiction of separate and hostile spheres, a job or labour contract was assumed to be either formal or informal, but not both. Nevertheless, under-declared formal employment clearly shows how labour can be concomitantly both formal and informal, meaning that the formal/informal divide is more blurred than previously considered in dualistic representations.

Formal employment not only overlaps with informal employment, but also formal unpaid labour. Again, various types exist. In the private and public sectors, formal unpaid labour can take the form of unpaid internships or one-week trials, and people do this expecting paid employment at the end. Sometimes, however, businesses fail to pay their formal employees for protracted periods (Shevchenko 2009), so it is not conducted as a matter of choice. It is in third sector organisations, nevertheless, that such labour is most extensive, and commonly termed ‘formal volunteering’, which refers to ‘giving help through groups, clubs or organizations to benefit other people or the environment’ (Low et al. 2008: 11). In some instances this can become ‘off-the-radar’ unpaid labour, when help is again provided through groups to benefit other people or the environment, but the formalities required by law have not all been fulfilled, such as when a children’s football coach volunteers but without have undertaken the required police checks. One-to-one unpaid labour refers to labour provided on an individualised level to members of households other than one’s own, such as kin living outside one’s household, friends, neighbours and acquaintances. This again is of different kinds, ranging from individualised one-way giving (often termed ‘informal volunteering’) to two-way reciprocity. When reciprocity is involved, such unpaid endeavour often blurs into reimbursed favours since the reciprocity may take the form of either in-kind labour or gifts in lieu of payment. Indeed, whether one-to-one labour when reimbursed in-kind or with gifts (as well as when paid) is closer to informal employment or to paid favours depends on the economic relations, values and motives involved. Financial gain is usually more prominent when more distant social relations are involved, and redistributive and relationship-building purposes more prominent when conducted for and by closer social relations, thus displaying how informal employment and reimbursed favours represent a continuum of, rather than separate, labour practices.

Turning to labour practices within the family household, most is self-provisioning, which is defined as unpaid work conducted by household members for themselves or for other members of their household. Sometimes, nevertheless, family members are reimbursed for tasks conducted for and by other household members using either money, gifts or in-kind reciprocal labour. Monetary payment is nearly always reserved for inter-rather than intra-generational exchanges (e.g. from a parent to a child). When gifts and in-kind reciprocal labour are included, however, the divide between monetised and non-monetised labour becomes blurred. Indeed, it is perhaps rare in couple households that domestic tasks are today conducted wholly unpaid with no expectation of future reciprocity. Even unpaid housework, an activity often viewed as wholly non-monetised and non-exchanged, is often embedded in expectations of reciprocity in couple households. Moreover, what constitutes family and non-family is by no means always clear cut, and therefore differentiating family work (self-provisioning) from one-to-one community exchanges is sometimes difficult, since current acquaintances, friends and even neighbours might well be past or future family. In what now follows, this TSOL analytical lens which depicts a seamless spectrum from formal to informal oriented practices, cross-cut by a continuum from reimbursed to non-reimbursed practices, is now applied to understanding the ‘economic’ in both Russia and Ukraine.

Evaluating the diverse economies of Ukraine

Following the demise of the Soviet Union, many ex-socialist nations have witnessed severe difficulties in making the transition to a market economy. Ukraine, the second largest successor state of the former Soviet Union, is no exception. Unemployment and labour market insecurity became a reality overnight (see Cherneyshev 2006; Lehmann and Terrell 2006; Standing 2005). Indeed, official employment declined by about one-third between 1990 and 1999 (Cherneyshev 2006), and despite the euphoria in Ukraine surrounding the ‘orange’ revolution and a ‘turn to the west’, economic difficulties have been a persistent feature of post-socialism.

‘Bribe taxes’, administrative corruption and ‘informal taxation’ are rife in everyday life and represent significant barriers to both economic growth and the formalisation of economic practices (Hanson 2006; Round and Kosterina 2005). Indeed, in global surveys, Ukraine is often identified as one of the most corrupt nations in the world. The World Bank’s ‘Doing Business 2009’ survey ranked Ukraine 145th of the 181 countries rated in terms of positive business climate, arguing that corruption and over-zealous bureaucracy stymies economic development (World Bank 2009). Ukraine was in 2009 ranked 180th out of 181 countries in terms of the ease of paying taxes (PricewaterhouseCooper 2009). A Transparency International (2005) survey, meanwhile, states that in Ukraine 82 per cent of respondents had recently paid a bribe to access services/goods to which they were entitled, the highest figure in the world. Although Anderson and Gray (2006) argue that the level of corruption is decreasing, they acknowledge there is still much work to be done.

It is perhaps little surprise, therefore, to find that when proxy indicators are used to measure the magnitude of informal employment, it is estimated to be equivalent to 47.3–53.7 per cent of GDP using physical input proxies (Schneider and Enste 2000) and 55–70 per cent using currency demand (Dzvinka 2002). Official Ukrainian government estimates, using indirect proxy methods, assert that some 55 per cent of Ukraine’s GDP is produced in the informal economy (NCRU 2005). In 2005, furthermore, and according to official state figures, approximately ten million Ukrainians, around 20 per cent of the population, were receiving incomes below the state subsistence minimum level. As Round and Kosterina (2005) highlight, however, even this subsistence minimum figure has little relevance since it only allows for an extremely basic diet, for clothes to be replaced every 3–5 years and assumes that the ‘market’ runs efficiently (i.e. that benefits and subsidies can be accessed). The reality, as Rose (2005) identifies, is that 73 per cent of Ukrainians receive insufficient from their main income to buy what they need to survive. Until now, however, and beyond the New Democracies Barometer (NDB) surveys conducted between 1992 and 1998 (Wallace and Haerpfer 2002; Wallace and Latcheva 2006), no contemporary studies have analysed the coping practices people use to get by in Ukraine.

To evaluate market penetration in Ukraine and document the multiple labour practices in this society, therefore, a survey was undertaken in late 2005 and early 2006 comprising face-to-face interviews with 600 households on their livelihood practices in a diverse range of localities. Given that previous studies in Europe reveal significant disparities in the types of economic practice used between affluent and deprived as well as urban and rural populations (Leonard 1994; Renooy 1990; Williams 2005a), maximum variation sampling was employed to select four contrasting localities. First, in the capital of Kyiv, an affluent area was chosen, namely Pechers’k, heavily populated by government officials and the new business class, along with a deprived neighbourhood, Vynogradar, comprising dilapidated Soviet-era housing with high unemployment and widespread poverty. Continuing the process of maximum variation sampling, a deprived rural area near Vasyl’kiv was then chosen, which relied heavily on a nearby refrigerator-manufacturing plant for its employment until it closed nearly ten years ago, and since then has suffered high unemployment; and finally, a town on the Ukrainian/Slovakia border was selected, Užhgorod, which is the administrative centre of the Zakarpattia Oblast province and where a concern exists among its population that inflated prices due to cross-border trade mean they cannot afford many goods and services. This survey, therefore, is not based on a nationally representative sample, and care should be taken to avoid generalising the results to the national level. It does, however, avoid surveying only one locality-type, which might have a very specific configuration of work and imply that this is more widely applicable by examining a diverse range of locality types.

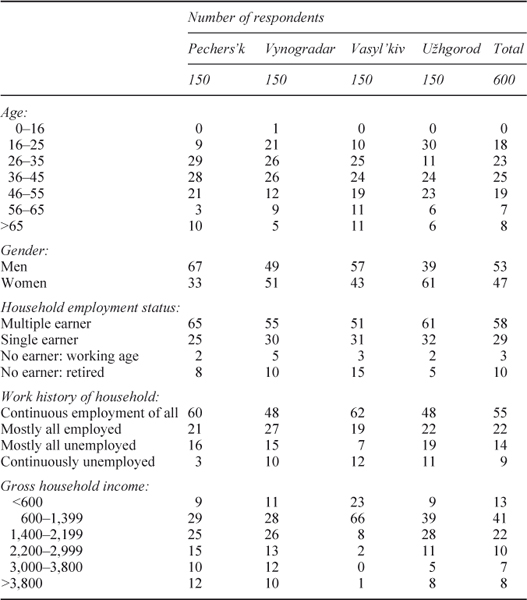

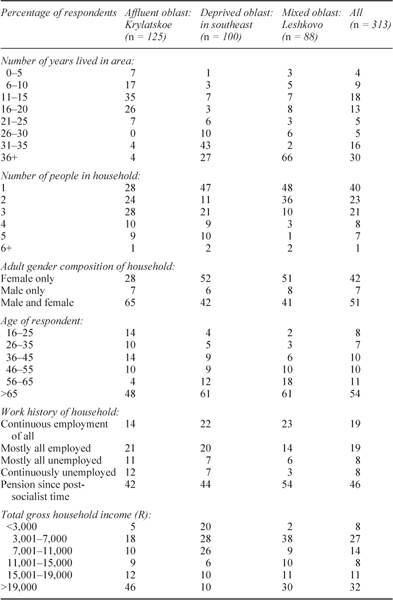

Within each locality, a spatially stratified sampling methodology was used to select households for interview (Kitchin and Tate 2001). In each locality, 150 interviews were conducted (600 in total). If there were 3,000 households in the area and 150 interviews were sought, then the researcher called at every twentieth household. If there was no response and/or the interviewer was refused an interview, then the twenty-first household was visited, then the nineteenth, twenty-second, eighteenth and so on. Table 4.1 provides an overview of the socio-economic profile of the respondents

Table 4.1 Socio-economic profile of respondents to Ukraine survey of livelihood practices, 2005–2006

Source: Ukraine survey.

To evaluate the labour practices supplied and used in Ukraine, structured face-to-face interviews were conducted. Besides gathering background data on gross household income, the employment status of household members, their employment histories, ages and gender, respondents were asked about the types of labour they used to secure their livelihood. Second, the labour practices that the household last used to complete 25 common domestic services were analysed; third, whether they had undertaken any of these 25 tasks for others during the past year using any of the ten labour practices; fourth, open-ended questions about each of the ten labour practices conducted and its relative importance to their household income; and fifth and finally, and using five-point Likert scaling, attitudinal questions concerning their ability to draw upon help from others and their views of the economy, politics, everyday life and their future prospects.

Beyond market hegemony: unravelling the plurality of labour practices in Ukraine

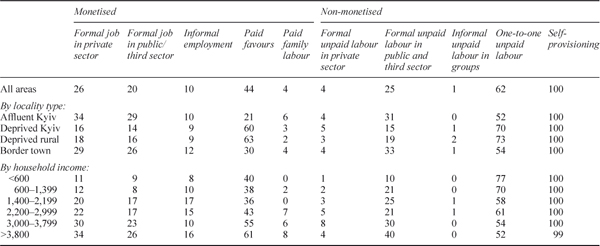

Table 4.2 reveals participation in the market to be not as extensive as sometimes assumed. Just 26 per cent of respondents had engaged in paid formal labour in the private sector during the previous 12 months. Relative to non-exchanged labour (which all respondents had conducted over the past year), one-to-one unpaid labour (which 62 per cent had conducted) and one-to-one paid community labour (44 per cent), participating in formal employment in the private sector appears confined to small pockets of the population with a similar participation rate to formal unpaid volunteering (25 per cent) and formal employment in the public and third sector (20 per cent). Participation rates in paid formal labour in the private sector display some marked socio-spatial variations from 11 per cent among the lowest-income households to 34 per cent in the highest-income households. It is not just this labour practice, however, which varies socio-spatially. Participation rates in all ten labour practices (with the exception of one-to-one non-monetised exchange) are generally higher in affluent than deprived populations.

Table 4.2 Participation rates in labour practices in Ukraine: by locality and gross household income

Source: Ukraine survey.

It does not necessarily follow that just because a labour practice is extensively used, households rely on it to secure their livelihood. Despite the relatively narrow participation rates in formal market labour, nearly one-third (32 per cent) of households chiefly depend on this labour practice to secure their livelihood. Over two-thirds (68 per cent) of households, therefore, primarily depend on practices other than private sector formal labour. Some 30 per cent chiefly rely on income from formal jobs in the public and third sector, 10 per cent on pensions/state benefits, 10 per cent on informal employment, 8 per cent on self-provisioning, 6 per cent on paid favours among close social relations and 4 per cent on unpaid one-to-one mutual aid.

Solely asking households about their primary livelihood practice, however, perhaps exaggerates the degree of reliance on the formal market economy. When also asked to name their second most important practice, just one in 25 households (4 per cent) depend entirely on the formal market economy and just one in ten households purely on formal income sources. The majority of households (96 per cent) either combine formal market labour with other practices (28 per cent) or else use some combination of labour practices that does not include formal market labour (68 per cent). To refer to Ukraine as a formal market economy, therefore, is a grave misnomer. Only one in 25 households define themselves as relying solely on the formal market economy to secure their livelihood. Instead, a plurality of labour practices is the norm. Households bundle together jobs in the formal sector, utilise the social welfare system, engage in subsistence production, and in community exchanges to secure their livelihood, as has been previously intimated in many other East-Central European countries (Smith and Stenning 2006; Wallace and Haerpfer 2002; Wallace and Latcheva 2006).

It is not just an examination of the labour practices supplied that highlights the diverse kinds of labour utilised in Ukraine. Evaluating the labour practices households last used to conduct 25 common domestic tasks, Table 4.3 finds that formal market labour was primarily last used in just 13 per cent of instances, displaying the limited commodification of domestic services in Ukraine. Indeed, only 25 per cent of domestic tasks involved any kind of paid labour; the remaining three-quarters used primarily unpaid labour, with some 71 per cent chiefly self-provisioning.

Source: Ukraine survey.

Nevertheless, there are differences across populations in both the permeation of formal market labour and the work cultures that prevail. As Table 4.3 reveals, higher-income households and those living in affluent localities more commonly use formal market labour to complete domestic tasks than lower-income households and those living in deprived areas. Indeed, the lowest-income households externalise to the formal market economy just 8 per cent of the 25 tasks surveyed compared with 44 per cent among the highest-income households. Similarly, while households in the affluent Kyiv district outsourced 20 per cent of the domestic tasks to formal market labour, this figure was just 6 per cent in the deprived rural area of Vasil’kiv.

The extent of outsourcing to formal market labour, however, is not the only difference in work cultures across populations. Populations use other labour practices to varying extents and also different combinations to secure their livelihood. Higher-income households and households in affluent areas, for example, use monetised labour practices to a greater extent than lower-income households and those in deprived areas who more heavily rely on community exchanges between closer social relations, both of the monetised and non-monetised variety, and non-exchanged labour. Socio-spatial variations exist not just in the extent of the permeation of the formal market economy and overall work cultures, but also in the nature of each labour practice in terms of its prevalence, the work relations and motives involved, and the extent to which such labour is concentrated at the overlap with other labour practices. To understand these socio-spatial variations, Part II of this book will evaluate each labour practice in turn. Before doing this, however, attention turns towards introducing a similar study of the diverse economies that prevail in the Russian global city of Moscow.

Evaluating the diverse economies in Moscow

To what extent has the formal market economy permeated the daily life of Muscovites? Do other labour practices persist, and if so, which kinds? And do the work cultures of Muscovites and the nature of individual labour practices vary socio-spatially? To answer these questions, the TSOL framework is here used to analyse evidence collected in 2005 and 2006 during 313 face-to-face interviews in Moscow, a global city of some 10.4 million inhabitants (Brooke 2006) where previous surveys reveal not only some marked cultural differences to the rest of Russia but also a long legacy of the use of work beyond formal employment (Brooke 2006; Caldwell 2004; Clarke 2002; Ledeneva 2006; Shevchenko 2009). This is also a global city that remains in transition to post-socialism, with the transformation being far from complete (Shevchenko 2009). As such, it is necessary to recognise that the forms of work organisation that prevail in different districts of Moscow are likely to be far from a steady-state.

As Clarke (2002) reveals in relation to Russia, moreover, during the Soviet period there were numerous services that no state enterprise provided and which were wholly delivered privately by individuals off-the-books, such as small construction and decorating jobs, repair of radios, televisions and washing machines, clothing repairs, care for the elderly and sick, private transport and private tuition. Indeed, until 1987, doing these odd jobs for pecuniary reward was illegal per se, despite citizens having no other way of obtaining such services. The outcome was a heavy reliance on informality in the so-called ‘second economy’ (Ledeneva 1998). Informal employment in the contemporary era, in consequence, has a different historical legacy for the population of Moscow in particular, and the ex-Soviet bloc more generally, compared with western economies and much of the third world. Furthermore, it is important to understand the context in which household employment decisions are made, especially Russian labour market legislation and the tax and benefits regimes. Superficially, taxation is extremely straightforward, with a uniform rate of 13 per cent on personal income and a corporation tax level of 20 per cent. In practice, however, it is more complex. As Round et al. (2008) outline, many formal employees receive two wages from their formal employer, one formal and the other in cash at the end of the month. This allows employers to evade payroll taxes and state pension contributions, and makes wage payments very uncertain for employees as they have no guarantee that their unofficial wage will be paid. If it is not, they have no recompense because if they complain to the state, they will be open to accusations of tax evasion on previously paid informal payments. Labour legislation is also extremely problematic in Russia. Although myriad labour regulations exist to protect workers, few are adhered to in practice (see Round et al. 2008). As Clarke (2002) displays, many people rely on contact networks to obtain employment, as opposed to applying for posts in open competition, and in some instances bribes are required to obtain employment (Round et al. 2008). In sum, great care is needed not to extrapolate the findings from this survey to either Russia more generally, post-socialist societies or other regions of the world. Instead, the intention here is solely to use this study of Moscow to begin to highlight how the TSOL varies across locality types within this global city so as to draw attention to the intra-urban variations in the TSOL, which can then be tested to see if they are also valid elsewhere.

Given that previous studies in Moscow (Pavlovskaya 2004; Shevchenko 2009), Russia (Clarke 2002; Kim 2002), East-Central Europe (Wallace and Haerpfer 2002; Wallace and Latcheva 2006; Williams 2005b) and western nations (Leonard 1998; Renooy 1990; Williams 2010a) identify significant variations in participation in formal and informal labour across affluent and deprived populations, the decision was taken to use maximum variation sampling to select three contrasting districts of Moscow to survey. First, an affluent region in the west of Moscow, namely Krylatskoe, was chosen; second, one of the most deprived regions located in the southeast of Moscow; and third and finally, a mixed region to the west of the Moscow region, about 25 km out from the Moscow ring road (which is the Moscow city border), namely Leshkovo, where ‘new Russians’ live in large expensive houses alongside benefit-dependent pensioners and the ‘working poor’.

In each region a spatially stratified sampling methodology was used to select households for interview (Kitchin and Tate 2001). If there were some 1,000 households in the region and 100 interviews were sought, the researcher called at every tenth household. If there was no response and/or an interview was refused, then the eleventh household was visited, then the ninth, twelfth, eighth and so on. This provided a spatially stratified sample of each region. In total, 313 face-to-face interviews were conducted in the three regions. The response rate for generating interviews at the original households was 15 per cent, 41 per cent when the households on either side are included and 68 per cent when the two households on either side are included. Although this survey is, of course, not representative of Moscow as a whole, it nevertheless unravels the multifarious kinds of labour being used in contrasting regions in this city and how work cultures and the nature of individual labour practices vary socio-spatially.

Table 4.4 outlines the socio-demographic profile of the participants in each of the three regions. This reveals that in the affluent region, the residents have lived there for much shorter periods than in the deprived and mixed region, the number of people in households is greater and there are more couple households, the average age is lower and the total gross household income is significantly higher. Similarly, although the deprived and mixed regions are similar in terms of the number of people in households, the gender composition of households, age profile of respondents and the work history of households, those in the mixed oblast have lived there longer than in the deprived oblast and the total gross household income in the mixed area reflects the polarised nature of household income levels, while the deprived oblast reflects the lower overall income levels. It is important to note, however, that not everybody in the relatively affluent oblast is on a higher income and not everybody in the deprived oblast on a lower income.

Table 4.4 Socio-demographic profile of participants in Moscow survey: by locality type

Source: Moscow survey.

To evaluate the plethora of labour practices used, previous studies indicate that respondents find it difficult to recall when various kinds of labour were used or supplied when open-ended, relatively unstructured interviews are employed (e.g. Leonard 1994; Pahl 1984; Williams 2004a). At the outset, therefore, the decision was taken to use structured interviews. Besides gathering background data on gross household income, the employment status of household members, their employment histories, ages and gender, first, respondents were asked about the forms of work they primarily and secondarily relied on to secure a livelihood, second, the sources of labour the household last used to complete 25 common domestic services so that comparative data was available across regions on the different labour practices used for the same set of tasks, third, whether they had undertaken any of these 25 tasks for others during the past year and, if so, what labour practice had been used. Fourth, open-ended questions were asked about any other work conducted using each of the eight labour practices; and fifth and finally, using five-point Likert scaling, attitudinal questions concerning their ability to draw upon help from others and their views of the economy, politics, everyday life and their future prospects.

The 25 common domestic services examined covered house maintenance (outdoor painting; indoor painting; wallpapering; mending a broken window; and maintenance of appliances), home improvement (putting in double glazing; plumbing; improving a kitchen; improving a bathroom), housework (routine housework; cleaning windows inside; doing the shopping; washing clothes; cooking meals; washing dishes; hairdressing; household administration), making and repairing goods (making or repairing clothes; making or repairing curtains; making or repairing tools; making or repairing furniture) and caring activities (daytime baby-sitting; night-time baby-sitting; tutoring).

Mapping the plurality of labour practices in Moscow

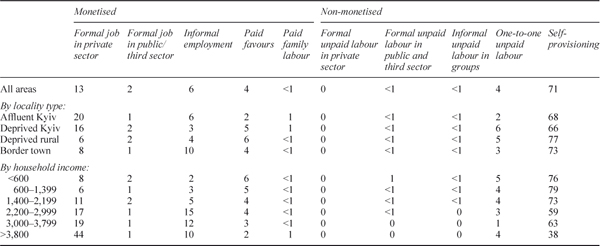

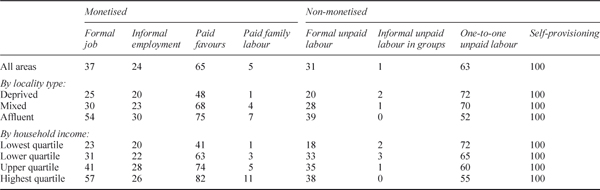

Table 4.5 reports the labour practices used to conduct a set of 25 common tasks across different regions and household income levels. The reason for using a set of 25 common everyday tasks was to allow comparative data to be gathered on the labour practices used for the same set of tasks. The finding is that participation in the formal paid labour market is not extensive in Moscow. Of course, this has to be seen in the context of the relatively large number of retired people interviewed. Nevertheless, only one-third (37 per cent) of respondents had engaged in formal paid employment over the past year even though 46 per cent of participants were of working age, meaning that one-fifth of working-age respondents has not engaged in formal paid employment during the past year. Relative to self-provisioning (which everybody had undertaken over the past year), unpaid one-to-one labour (which 63 per cent had conducted) and paid favours (65 per cent), participation in the formal labour market is thus confined to small pockets of the Muscovite population.

Table 4.5 Participation rates in labour practices in Moscow: by locality and gross household income

Source: Moscow survey.

Nevertheless, participation rates vary socio-spatially. Engagement in formal paid employment ranges from 25 per cent in the deprived district, through 40 per cent in the mixed district, to 54 per cent in the affluent district, with greater proportions of the working-age population not engaging in formal employment in the deprived than affluent district (36 per cent compared with 7 per cent). Similarly, participation in formal employment was just 25 per cent among those adults living in the lowest-income quartile of households, but 31 per cent in the lower middle-income quartile, 41 per cent in the upper middle-income quartile and 57 per cent in the highest-income quartile. However, it is not just engagement in formal paid employment which varies socio-spatially. Participation rates in all eight labour practices (with the exception of unpaid one-to-one labour and off-the-radar unpaid labour in organisations) are higher in the affluent compared with deprived populations. In Moscow, therefore, there appear to be relatively ‘work busy’ populations engaged in a wide range of labour practices, especially market-oriented and monetised practices, and relatively ‘work deprived’ populations engaged in a narrower range of practices.

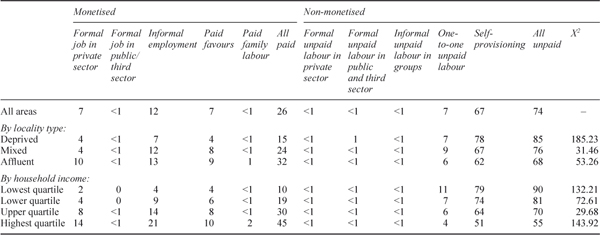

The socio-spatial variations in the penetration of capitalism and the differences in the organisation of labour can also be seen when one examines the practices that households in different districts use to get by in everyday life. Evaluating the source of labour last used to conduct 25 common domestic service tasks, as Table 4.6 reveals, the finding is that there is a relatively shallow permeation of daily life by formal labour. Formal labour, for instance, was last used in just 7 per cent of instances to get these common domestic tasks completed. Indeed, only 26 per cent of domestic tasks even involved paid labour; the remaining three-quarters were last conducted by unpaid labour, with some two-thirds (67 per cent) conducted on a self-provisioning basis.

Source: Moscow survey

Note

Χ2 > 23.589 in all cases, leading us to reject H0, within a 99.5 per cent confidence interval, that there are no household income or spatial variations in the sources of labour used to complete the 25 everyday domestic services.=

Nevertheless, there are differences across populations in both the permeation of formal labour and their overarching work cultures. As Table 4.6 reveals, people living in the affluent district more commonly use formal labour in particular, and paid labour in general, than those in the deprived district. The vast majority of outsourcing of domestic tasks among the Moscow households surveyed, however, is to paid informal labour rather than to the formal economy. The degree to which households externalise to the monetised and formal sphere is not the only difference in work cultures across populations. Other labour practices are also used to differing extents and in varying combinations. Those living in deprived districts more heavily rely upon self-provisioning and unpaid one-toone labour. So, too, do those households in the lowest-and lower middle-income quartile compared with more affluent households, who rely more on paid favours, informal employment and formal labour.

The overarching finding, however, is not simply that relatively affluent populations are more likely to engage in formal and paid labour practices while deprived populations are more likely to engage in informal and unpaid labour practices. This is only a partial representation of the socio-spatial variations in the organisation of labour. Rather, there seems to exist a spectrum ranging from relatively affluent ‘work busy’ populations who engage in a multitude of labour practices (as shown by their higher participation rates in most sources of labour) to relatively disadvantaged ‘work deprived’ populations who conduct a much narrower range of practices. Socio-spatial variations prevail not just in the penetration of formalisation and the range of and type of labour practices conducted, but also in the nature of each labour practice used in terms of the work relations and motives involved. To understand these socio-spatial variations in individual labour practices, each will be evaluated in Part II of this book.

Conclusions

To start to question the narrative of the impending hegemony of the formal market economy in post-Soviet societies, this chapter has sought to further advance the emergent ‘diverse economies’ literature by developing an analytical lens for representing the multiple labour practices in economies. Moving beyond the simplistic formal–informal economy dichotomy, this chapter has conceptualised the multiple kinds of labour that exist in post-Soviet societies by adopting a ‘total social organisation of labour’ approach. This conceptualises a spectrum from formal-oriented to informal-oriented labour practices, which is cross-cut by another spectrum ranging from wholly monetised to wholly non-monetised labour practices. The resultant outcome is to provide an analytical lens for capturing the plurality of labour practices that exist in post-Soviet societies in a manner which shows how they all seamlessly merge into each other.

Having developed this typology, this has then been used to provide an over-arching understanding of the multifarious labour practices used in Ukraine and Russia. Analysing the results of 600 interviews conducted across various populations in Ukraine and 313 interviews conducted in Moscow, this has first shown the shallow permeation of the formal market economy in Ukraine and Russia that have been supposedly undergoing a ‘transition’ to formal market economies. It has also revealed the existence of diverse work cultures across different populations, along with marked socio-spatial variations in the nature of individual labour practices. To begin to develop a deeper understanding of these socio-spatial variations in individual labour practices, attention turns in the following chapters to evaluating each of the eight forms of labour that are used to secure a livelihood in post-Soviet societies.