Introduction

Informal employment is here defined as paid labour unregistered by or hidden from the state for tax, social security and labour law purposes (European Commission 2007). Akin to the other eight labour practices considered in this book, different varieties exist, ranging from waged informal employment where employees are employed on an undeclared basis by formal or informal businesses to informal self-employment which can be conducted by own-account workers who work either wholly or partially off-the-books.

In this chapter, the intention is to evaluate the prevalence and nature of informal employment in post-Soviet/socialist spaces. To achieve this, first, a brief review is undertaken of the different methods of measuring informal employment and the varying estimates produced by such methods of the magnitude of informal employment in post-Soviet/socialist societies. Second, and so as to provide a richer and more textured understanding of how informal employment is embedded in daily life in post-Soviet societies, empirical evidence from Ukraine is reported, followed in the third section by evidence from Moscow. This will reveal not only the multifarious forms of informal employment in post-Soviet societies, but also how informal employment is not a distinct category but merges into the other forms of labour considered in other chapters. At the outset, however, it is necessary to be clear what is being discussed in this chapter. Despite being variously referred to by 45 adjectives, such as ‘cash-in-hand’, ‘informal’, ‘black’, ‘underground’, ‘hidden’ and ‘shadow’ and 12 nouns including work, employment, economy and sector (Williams 2004a), there is a strong consensus regarding the types of endeavour included and excluded when discussing this form of work. Informal employment is widely accepted as involving only the production and sale of goods and services that are licit in all respects besides the fact that they are unregistered by or hidden from the state for tax, benefit and/or labour law purposes (European Commission 1998; Feige 1999; Portes 1994; Renooy et al. 2004; Thomas 1992; Williams 2006a; Williams and Windebank 1998). When the goods and services provided are illicit (e.g. drug-trafficking), such endeavour is excluded, as are non-cash exchanges and subsistence production that is not exchanged. Blurred edges, nevertheless, do remain. As shown in the previous chapter, informal employment overlaps with formal employment since formal employees often receive undeclared wages from their formal employer. In this chapter, however, this is excluded since it was discussed in the previous chapter. There are also blurred edges between informal employment and paid favours (discussed in Chapter 7) since informal self-employment merges with paid favours, depending on the economic relations involved and the motives of the participants.

Participation in informal employment in post-Soviet/socialist societies

Different measurement methods produce different estimates of the prevalence of informal employment in post-Soviet societies. Here, we briefly review the measurement methods used and their estimates of its size. To do this the indirect measurement methods will be reviewed, followed by the more direct survey methods.

Indirect methods for measuring informal employment

Indirect methods seek evidence of informal employment in macroeconomic data collected and/or constructed for other purposes. These indirect methods have been of three broad types. First, there are those seeking statistical traces of informal employment in non-monetary indicators. The most common methods using such non-monetary surrogate indicators are, first, those that seek traces in formal labour force statistics (e.g. Alden 1982; Crnkovic-Pozaic 1999; Del Boca and Forte 1982; Hellberger and Schwarze 1986), second, those that use very small enterprises as a proxy (e.g. ILO 2002a; Portes and Sassen-Koob 1987; Sassen and Smith 1992; US General Accounting Office 1989) and, third, those that use electricity demand as a surrogate (e.g. Friedman et al. 2000; Kaufmann and Kaliberda 1996; Lacko 1999). Second, there are methods that employ monetary proxy indicators to estimate the magnitude of informal employment. Three principal proxies have been used: large denomination notes (Bartlett 1998; Carter 1984; Freud 1979; Henry 1976; Matthews 1982); the cash–deposit ratio (e.g. Atkins 1999; Caridi and Passerini 2001; Cocco and Santos 1984; Matthews 1983; Matthews and Rastogi 1985; Meadows and Pihera 1981; Santos 1983; Tanzi 1980); and the total quantity of money transactions (Feige 1979, 1990; Isachsen et al. 1982), although a multiple indicators, multiple causes (MIMIC) approach has emerged that has perhaps become the most commonly used indirect method for measuring the magnitude of informal employment (Bajada and Schneider 2003; Chatterjee et al. 2002; Giles 1999a, 1999b; Giles and Tedds 2002; Schneider 2001, 2011; Schneider and Enste 2002). Third, there are those methods analysing discrepancies between income and expenditure levels either at the aggregate national level (Apel 1994; Hansson 1982; Langfelt 1989; Paglin 1994; Park 1979; Tengblad 1994), or through detailed microeconomic studies of different types of individuals or households (Dilnot and Morris 1981; Macafee 1980; O’Higgins 1981), premised on the assumption that even if the informally employed can conceal their incomes, they cannot hide their expenditures.

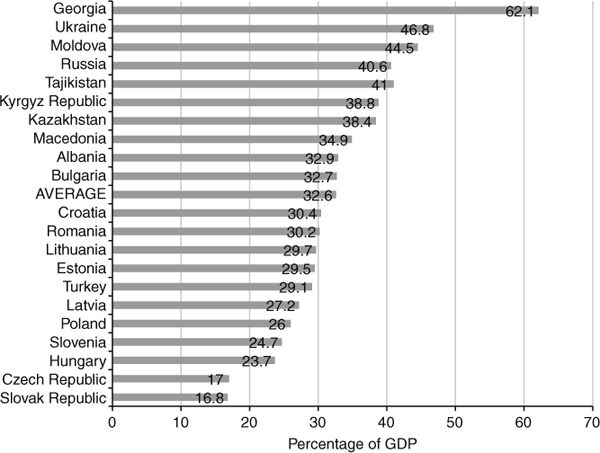

Given that there are already many in-depth critical reviews of the advantages and disadvantages of all these different indirect measurement methods (Bajada 2002; Feige and Ott 1999; OECD 2002; Schneider and Enste 2002; Williams 2004a, 2006b), we will not repeat the findings. Suffice it to say that despite each and every method suffering from some serious shortcomings, there has emerged a consensus that while direct survey methods (considered below) should be used to understand the nature of informal employment in terms of the types of informal work that take place, who does it and their motives, indirect methods can produce overall estimates of the relative magnitude of informal employment in different places (European Commission 2007; OECD 2011; Williams 2006b). Indeed, for well over a decade now, the MIMIC approach, despite recognition of its shortcomings, has become the standard means of estimating the magnitude of informal employment in different countries. This views the causes (and indicators) of informal employment as: the burden of direct and indirect taxation, both actual and perceived; the burden of regulation; and tax morality (citizens’ attitudes towards paying taxes). Figure 6.1 reports the estimated magnitude of informal employment in post-Soviet/socialist societies using this MIMIC measurement method (Schneider 2012). Here we report the results for 2007, when we conducted our fieldwork in Russia and Ukraine. This reveals that the magnitude of informal employment in post-Soviet/socialist economies was on average equivalent to 32.6 per cent of GDP, although its magnitude varied from the equivalent of 16.8 per cent of GDP in Slovenia to 62.1 per cent in Georgia at this time. It also importantly reveals that Ukraine and Russia were, in 2007, among the countries with the highest levels of informal employment in the post-Soviet/socialist world, with informal employment estimated to be equivalent to 46.8 per cent of GDP in Ukraine and 40.6 per cent of GDP in Russia.

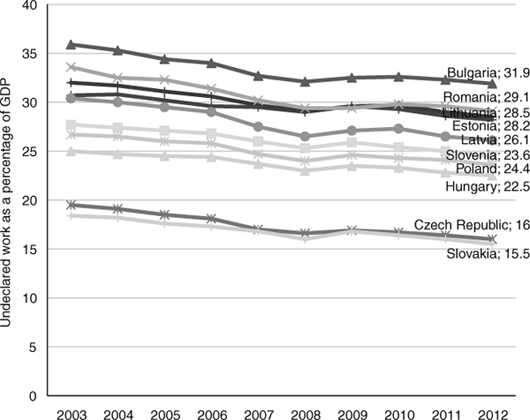

This MIMIC measurement method also provides data on whether informal employment is growing or declining relative to the formal economy over time. Figure 6.2 reports the results for post-Soviet/socialist economies. It reveals that besides a slight rise between 2008 and 2009, when the economic crisis started to hit hard, there has been an ongoing decline in informal employment in these post-Soviet/socialist societies between 2003 and 2012. During the current economic crisis, therefore, informal employment according to this measurement method has been declining as a proportion of GDP in those post-Soviet/socialist economies for which such longitudinal data is available.

However, caution is urged when considering these results. It is not only possible to challenge all of the supposed causes (and indicators) used by this approach, but there is also little recognition in this approach that it is not these factors per se but, rather, how they combine with a multitude of others factors that produces high or low levels of informal employment. It is also important to recognise that to understand the role of informal economies in post-Soviet/socialist economies, it is not so much the magnitude of informal employment that needs to be understood, but rather how the informal employment is being used in everyday livelihood practices and by whom and for what reasons. To seek understanding of these issues that provide us with a more textured comprehension of the role of informal economies in the post-Soviet/socialist world, it is the direct survey methods that are a more useful tool.

Direct survey methods

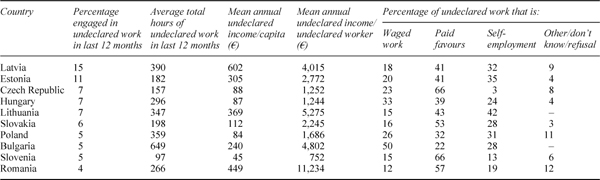

Rather than use proxy indicators to evaluate the magnitude and/or character of informal employment, a parallel stream of research has conducted direct surveys of informal employment using both mail shots as well as various interview methods (e.g. Boren 2003; Burawoy and Verdery 1999; Meurs 2002; Pavlovskaya 2004; Smith 2002a, 2002b, 2004, 2010; Smith and Stenning 2006). Most of these have been studies of single nations and small-scale qualitative surveys. Although these are useful, as will be seen below, for unpacking rich and textured understandings of the nature of informal employment, they have been less useful for getting a feel for the cross-national variations in the magnitude of informal employment. One exception is the 2007 Eurobarometer survey which measures the participation rates in informal employment using the same questionnaire survey method across a range of post-Soviet/socialist countries. Table 6.1 reports the results. This displays that participation rates range from 15 per cent in Latvia and 11 per cent in Estonia to 4 per cent in Romania. This does not mean, however, that the undeclared economy (i.e. informal employment and paid favours) is necessarily more extensive in those nations with higher participation rates. As can be seen, in nations such as Romania, the average hours worked in the undeclared economy is higher as is the average income earned from such work. In consequence, although a smaller share of the population engage in the undeclared economy in some countries, they work for more hours than those in countries with higher participation rates where the undeclared economy appears to be composed of smaller-scale and piecemeal activities such as baby-sitting and odd-jobs.

Table 6.1 Prevalence and configuration of the undeclared economy in East-Central European countries

Source: Eurobarometer survey on undeclared work, 2007.

So, too, does the configuration of informal employment vary across nations. As displayed in Table 6.1, marked variations exist in the proportion which is waged employment, self-employment and paid favours for closer social relations. For the moment, paid favours will be excluded from the analysis since this will be treated separately in Chapter 7. In this chapter the focus is upon the ratio of informal waged employment to informal self-employment. Examining Table 6.1, it becomes apparent that this ratio significantly varies across countries. In Bulgaria, for instance, nearly twice as much informal waged employment takes place as informal self-employment, while in Slovakia the opposite is the case: participation in informal self-employment is nearly twice as likely as participation in informal waged employment. It is important to be aware, therefore, that informal employment is often very differently configured in different post-Soviet/socialist societies.

Here, therefore, and to provide a richer and more textured understanding of the role of informal employment in the livelihoods of those living in post-Soviet/socialist societies, we begin to unpack the more qualitative meanings of informal employment to those engaged in it in terms of the role of such work to those engaged in it. To do this, we report the findings of our fieldwork using a direct survey method conducted in Ukraine and in the Russian city of Moscow.

Prevalence and nature of informal employment in Ukraine

Asking the 600 respondents about the form of work most important for their standard of living, along with what the second most important is, one in six (16.4 per cent) households report that they rely primarily on informal employment for their livelihood. A further quarter, citing some other form of work as their principal source of livelihood, moreover assert that informal employment is the second most important contributor. In total, therefore, 40 per cent of Ukraine households cite informal employment as either the principal or secondary contributor to their living standard. To depict informal employment as a residual and weak realm is thus a misnomer in Ukraine.

Who, therefore, relies on informal employment for their livelihood? Evaluating the structuralist view discussed in Chapter 3 that it is marginalised populations excluded from the formal economy, the finding is that just 13 per cent of households with nobody in formal employment cited informal employment as their primary strategy, but 24 per cent of households with one formal wage earner and 14 per cent of households with multiple formal wage earners. Indeed, of all households chiefly relying on informal employment for their livelihood, just 6 per cent were households with nobody in formal employment (12 per cent of all households surveyed), 51 per cent were multiple-earner households (58 per cent of households surveyed) and 43 per cent single-earner households (29 per cent). Analysing whether it is nevertheless the jobless in these households who engage in informal employment, the finding is that in multiple-earner households, it is in 96 per cent of cases those with formal jobs who engage in informal employment, while in single-earner households it is in 70 per cent of cases the formal wage worker who also undertakes the informal employment. Therefore, informal employment is not confined to those excluded from the formal labour market as suggested by structuralist accounts of the informal economy.

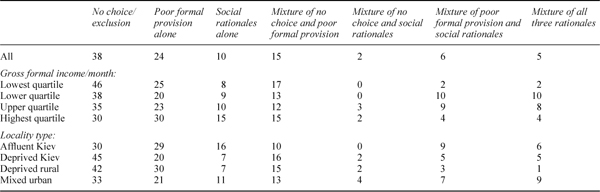

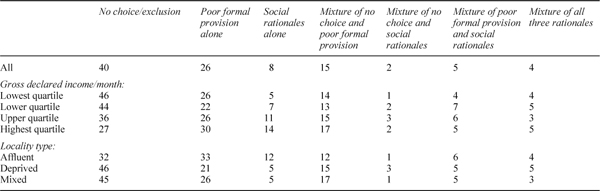

Do people operate in this sphere, therefore, due to their exclusion from the formal economy (as structuralists assert) or because they are voluntarily exiting the formal realm either because of the problems associated with working legitimately (as neo-liberals assert) or for rationales more grounded in social and redistributive motivations (as post-structuralists assert)? To evaluate this, first, the rationales of consumers will be evaluated, and second, the rationales of suppliers. Examining the reasons consumers gave for using informal employment, as Table 6.2 displays, some 38 per cent of off-the-books transactions were sourced because they had no choice but to do so, and a further 22 per cent included this issue in their explanation. For many, therefore, informal employment was used in preference to the formal economy. For neo-liberals this explanation covers problems associated with sourcing formal goods and services, including the availability, quality and speed of formal service provision. For example, it might be stated that formal businesses often do not turn up to give quotes for work and/or fail to turn up to do the work and even if they do turn up, tend to only partially complete the work and then move to another job until harried to return and finish the work. In this study, some 24 per cent of off-the-books transactions were conducted purely for this reason and a further 26 per cent included this issue in their rationale. Meanwhile, post-structuralists assert that participation is also out of choice, but explain this in terms of social or redistributive rationales. The finding is that some 10 per cent of informal labour was used due to either a desire to help someone who is in need of money and/or as a favour among friends, colleagues and acquaintances. A further 13 per cent included this issue in their explanation. In reality, of course, such social/redistributive explanations are often embedded in economic rationales in that the reason that a neighbour or friend is being asked to do a task is to redistribute money to them in a way that does not appear to be ‘charity’.

Table 6.2 Consumers’ motives for using informal labour in Ukraine: by population group

Source: Ukraine survey.

Consumers’ rationales, nevertheless, vary across populations. Indeed, while ‘exclusion’ drivers are more commonly cited among low-income households and those living in deprived neighbourhoods, ‘exit’ drivers, particularly regarding poor formal provision, are more frequently cited among high-earners and those in affluent and rural areas. Social/redistributive rationales, meanwhile, are more frequently the chief rationale among higher-income households and affluent urban areas. The result is that participation in informal employment for low-income groups and those in deprived areas is more a result of exclusion, while engagement among high-income groups and those living in affluent areas is more due to voluntary exit. In consequence, different explanations are relevant to different groups.

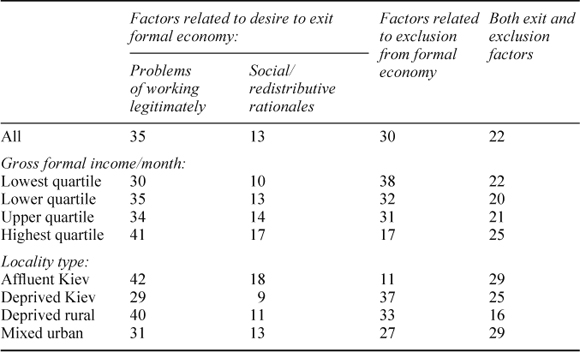

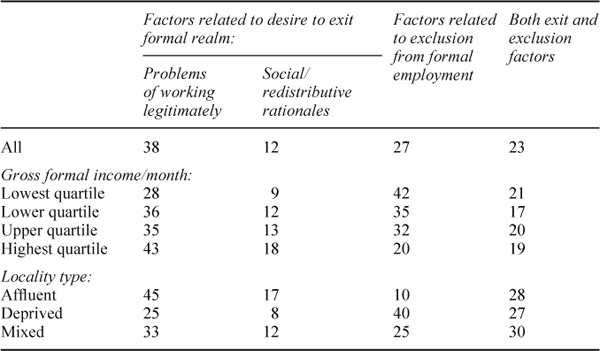

Turning to suppliers’ rationales, Table 6.3 again divides rationales according to whether the primary reason cited is exclusion (e.g. because they could not find a regular job, the employer insisted on them being paid off-the-books or because there is no alternative) or whether it is more a decision to exit, and if so, whether this is because of the problems of working legitimately or whether it is more for social/redistributive rationales. The finding is that 30 per cent of informal employment is explained purely in terms of exclusion from the formal economy, 48 per cent solely due to a desire to voluntarily exit the formal economy, as argued by neo-liberal and post-structuralist commentators, and 22 per cent for a mix of both exit and exclusion rationales. Breaking down the decision to voluntarily exit the formal economy, 35 per cent of all informal employment was to avoid the costs, time and effort of formal registration and in preference to formal employment and 13 per cent for social and/or redistributive reasons, such as a desire to help someone who is in need of help who would otherwise be unable to afford to get the work completed.

Source: Ukraine survey.

Again, however, the rationales vary across population groups and areas. Voluntarism, and therefore the neo-liberal and post-structuralist explanations, is more commonly cited by informal workers living in higher-income areas, rural areas and affluent localities. The structuralist assertion that participation is more the result of exclusion from the legitimate realm, meanwhile, is more common among low-income households, and those living in urban and deprived areas. It is not just across different socio-economic and spatial populations, however, that there are variations in the reasons for participating in informal employment.

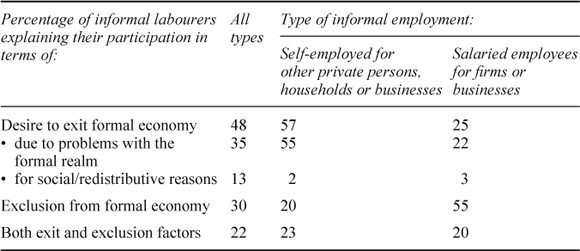

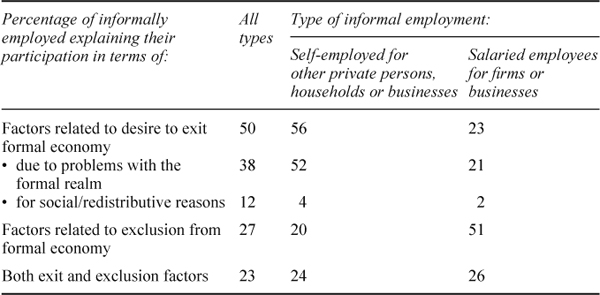

Do the reasons vary, however, according to whether it is informal self-employment or waged informal employment that is being conducted? This survey finds that of all informal employment undertaken, 38 per cent is informal self-employment and the remaining 62 per cent is waged informal employment. Examining the reasons for participating in each of these different types of informal employment, Table 6.4 reveals that those studying informal employment from the perspective of exclusion are more likely to find what they seek in waged employment; some 55 per cent is conducted for factors related to exclusion and 20 per cent for rationales associated with both exit and exclusion, compared with just 20 per cent and 23 per cent, respectively, of informal self-employment. Similarly, the desire to exit the formal economy is greater in own-account work. Neo-liberals depicting participation more as a voluntary decision to exit the formal economy so as to avoid the costs, time and effort of formal registration, therefore, have been correct to focus upon informal self-employment (55 per cent of self-employment is conducted for this reason), while post-structuralists depicting engagement to be a choice conducted for social/redistributive rationales have been correct to focus upon own-account work embedded within closer social networks of familial and community solidarity (46 per cent is conducted for such reasons).

Table 6.4 Relationship between type of informal employment and reasons for participation in Ukraine

Source: Ukraine survey.

It is important to be aware, however, that even if there is a close relationship between these different varieties of informal employment and the contrasting explanations, it is far from the case that all work in each category can be explained purely in terms of simply either exclusion or exit. To see this, each variety of informal employment is briefly reviewed in turn.

Informal waged employment in Ukraine

Examining waged informal employment, one finds considerable support for the structuralist representation of informal employment as conducted under ‘sweatshop-like’ conditions, as becoming an inherent part of employment practices in capitalism, as possessing largely negative attributes and impacts, and as conducted out of necessity rather than choice (e.g. Bender 2004; Castree et al. 2004; Espenshade 2004; Hapke 2004; A. Ross 2004; R. Ross 2004), especially in the garment manufacturing sector (e.g. Bender 2004; Espenshade 2004; Hapke 2004; Ram et al. 2002a, 2002b; R. Ross 2004). Although informal employees were identified working in wholly off-the-books businesses under ‘sweatshop-like’ conditions, such as in clothing manufacturers, mostly out of necessity, these employees represent only one segment of all informal waged employees in Ukraine. Waged informal employment takes many forms, as Clarke (2002) has identified in Russia. Some 20 per cent of waged informal employees work for wholly informal businesses, with the remaining 80 per cent working for legitimate businesses on an informal basis. Such work, moreover, is sometimes full-time (30 per cent of such work) but more often part-time, temporary or occasional.

Neither are they all in the lowest-income groups. Some 53 per cent of informal employees were in the lowest quartile of households by total gross household income, 30 per cent in the second quartile, 15 per cent in the third quartile and just 2 per cent in the highest income quartile. Examples of the work they undertake are multifarious. However, they were clustered in the construction and consumer service sectors in jobs such as labourers on building sites, taxi drivers, market stall workers, and waiters and cooks. Moreover, 55 per cent of informal waged workers say that they work in this realm due to their exclusion from the formal realm, 25 per cent for reasons related to a desire to exit the formal economy and 20 per cent for a mixture of both exclusion and exit factors (see Table 6.4). For example, respondents commonly asserted that ‘I did it because no other work was available’, ‘I did it to earn much needed extra cash’ and ‘I do it because I need the money.’ Although other reasons prevailed, such as to help out the owner of the business (e.g. ‘he needed staff so I helped him out; he is an acquaintance’), most is conducted out of economic necessity and/or because they had no other choice. On the whole, in consequence, informal waged employment is more likely to be a product of exclusion than other forms of informal employment.

Informal self-employment in Ukraine

The 600 face-to-face interviews revealed a high level of self-employment in Ukraine. Some 331 individuals living in these households had engaged in some form of self-employed activity in the past three years. Of these, just 33 (10 per cent) stated that this activity was wholly legitimate and that they had registered this activity with the state, had been in possession of the required licences and had conducted all their transactions on a formal basis. The remaining 298 (90 per cent) operated wholly or partially in the informal economy. Some 39 per cent had a licence to trade and/or the person was registered as self-employed, but a portion of their activity was conducted in the informal economy, while 51 per cent operated on a wholly unregistered basis with no licence to trade and conducted all of their activity in the informal economy (see Table 6.5).

Table 6.5 Share of self-employed working wholly or partially informally in Ukraine

| All | Men | Women | |

Number | 331 | 161 | 170 |

Percentage operating informally | 90 | 89 | 91 |

Percentage wholly legitimate | 10 | 11 | 9 |

Percentage registered but conducting share of trade off-the-books | 39 | 46 | 31 |

Percentage not registered | 51 | 43 | 60 |

Source: Ukraine survey.

Are there variations between men and women who are informally self-employed in terms of the portion that trade off-the-books and the type of off-the-books business that they operate? The finding is that although similar proportions of women and men who are self-employed trade off-the-books, men are more likely to operate registered enterprises and to conduct a portion of their transactions off-the-books, while women are more likely to operate unregistered enterprises and to trade wholly off-the-books. Examples of such wholly informal businesses operated by women include: a childcare business operated from home by a grandmother responsible for providing the daytime care for her preschool grandchild; a home-based catering business which undertook work for both domestic and commercial customers; a business making curtains and other soft furnishings; an enterprise making and repairing clothes; a pensioner who supplemented her state pension by selling cigarettes at a train station, and an illegal street vendor who sold flowers which she grows on her dacha just outside a market. All were unregistered enterprises trading wholly in the informal economy.

Who, therefore, engages in such informal self-employment? Some 55 per cent are in formal employment, operating their business alongside their formal waged work as an ‘on-the side’ activity, and the remaining 45 per cent are a mixture of various categories of people registered as non-employed, including the ‘economically inactive’ such as housewives and others unregistered as engaging in any form of employment, pensioners and people claiming unemployment benefit. This reinforces the wider finding elsewhere that those starting-up enterprises often tend to be people in waged employment and that it is only later in the development of the enterprise that they might become fully self-employed and to leave their waged employment (e.g. Reynolds et al. 2002). As a study in Russia has displayed, 26.5 per cent of the newly self-employed work on an informal basis as a second job at the outset, displaying how the informal sphere is an incubator for new self-employed businesses (Guariglia and Kim 2006).

Of those engaged in such self-employed activity that currently also engage in waged employment, about 80 per cent use the skills, tools and/or networks directly related to their employment and/or employment-place in their informal self-employment. For example, those working as plumbers in their formal occupation tend to operate plumbing enterprises ‘on the side’ and others tend to use contacts from their employment-place in order to find work for their informal enterprise. An example would be university teachers who offer university entrance examination candidates tuition on an informal basis in order to help them pass their entrance examinations. The remaining one-fifth of those in waged formal employment operating an informal enterprise do so in fields that arose out of what Stebbins (2004) refers to as some ‘serious leisure’ such as a hobby or interest that leads them to set up enterprises selling goods produced or services resulting from it. This included those who had learned some skill by pursuing some hobby or interest (e.g. painting, carpentry) and had then decided to establish an enterprise based on this skill. This Ukraine survey reveals that nine out of ten starting up a self-employed enterprise in the last three years had chosen to work on an informal basis, and some two-thirds had still not even registered their enterprises and were working wholly off-the-books. For most of these informal self-employed, the formal economy was seen as possessing largely negative attributes and impacts due to the existence of corrupt state officials and their lack of belief that taxes would be used for the social good, while the informal economy was perceived as a positive alternative that gave them free rein and was largely entered out of choice rather than necessity. Looking at this group of informal workers and type of work, there is thus superficially strong support for the representation of the informal economy as an alternative economy and sphere of resistance, as has been previously identified elsewhere (De Soto 1989; Williams 2006b).

This, however, depends on the group of informal self-employed considered. This is because the informal self-employed are clustered at the two ends of the income spectrum. In the lowest quartile of households surveyed in terms of gross income, one finds clustered 35 per cent of the informal self-employed in Ukraine, while in the highest quartile of households one finds 41 per cent of all informal self-employed. Those informal self-employed in the lowest quartile largely do not have a formal job (85 per cent of them) and engage in own-account work as a survival strategy. This is mostly poorly paid work, such as selling flowers outside street markets, cigarettes outside stations or providing routine domestic services. Indeed, the vast majority of respondents asserted that they would prefer a ‘normal’ formal job so as to minimise their risks of being cheated, robbed and to be able to have paid leave, but did not have the opportunity to do so. Instead, they had to rely on largely piecemeal informal own-account work. As such, these necessity-oriented informal self-employed adhere to the by-product depiction of the informal employed as those off-loaded by capitalism forced to eke out a living in this sphere as a last resort. Those informal self-employed in the highest quartile in terms of gross household income, however, usually engage in relatively well-paid informal self-employment, which in nearly half (45 per cent) of all such cases directly arises out of opportunities from their formal employment or self-employment. This includes not only university teachers who provide preparation for the university entrance examinations and school teachers who provide after-school additional lessons for pupils, but also software engineers providing informal services for the clients of the business where they are formally employed, and self-employed plumbers, electricians and builders conducting a portion or all of their business informally. Nearly all asserted that they worked informally so as to avoid the ‘bribe taxes’, administrative corruption and ‘informal taxation’ rife in Ukrainian public life (Hanson 2006; Round and Kosterina 2005; Wallace and Latcheva 2006). ‘Katrina’, who runs a catering business, reflects the opinion of many of these higher-income own-account informal workers interviewed when she states:

I would like to have my own ‘legit’ business. I would be very proud… . People would look at me differently … but it is very difficult … our ‘chinnovniki’ [government officials] want money, money and more money but I cannot afford to do that… . It is a shame because it has always been my dream to be a ‘khozyaika’ [enterprise owner], but it isn’t to be.

She wanted to go ‘legit’ but currently could not see how this could be achieved because public officials would demand cash payments from her for the required licences and to remain in business.

For most of the higher-income self-employed, it was perceived to be far too difficult to legitimise their operations. A self-employed taxi driver in his fifties neatly summed up the feeling of most of these respondents when he stated:

I have never thought about getting a licence because it is a very complicated bureaucratic process. I just do not have time and the nerve to stand in lines for days and weeks. It is amazing; if the state wants taxes why does it not organise things so that all the procedures to get a licence go quickly and without bribes? I have the impression that if a person wants to pay taxes out of his/her informal income in this country, they have to be obsessed by this idea and fight for their rights to do it with the state itself.

Most of the higher-income self-employed running wholly illegitimate businesses, moreover, saw nothing wrong in doing so. For them, it was the state and its officials who were corrupt and they who were in the right. They saw themselves as entrepreneurs and part of the burgeoning ‘capitalist’ culture in Ukraine, but operating informally due to the corruption, bribery and bureaucracy inherent in the ‘old’ system that they were helping replace. Many were also very willing to pay taxes but refused to do so while the income went into what they believed to be the pockets of state officials rather than being used for the public good. The motives of such respondents, therefore, very much reflect the thesis that depicts informal employment as a chosen alternative to a harmful formal economy that is putting a brake on economic development and growth.

In sum, the informal self-employment identified in Ukraine is not a complement to the formal economy since it is not simply reinforcing the disparities produced in the formal economy, but neither is it purely either a by-product or alternative to the formal economy. Although lower-income informal own-account workers reinforce the by-product thesis of marginalised groups engaged out of necessity in this work, higher-income own-account workers reflect the view that it is a chosen alternative to a failing bribe-ridden and corrupt formal economy. For the vast majority of the informal self-employed, nevertheless, such informal self-employment is central to their livelihood.

It is not an aim of the above arguments to over-romanticise the observed informal practices as alternatives to formal market processes. However, their widespread existence questions the stories of the formal market economy’s successful creation that the state and outside actors such as the EU promulgate. Simply put, Ukraine’s formal market economy could not function without the informal, as such activities enable individuals to perform their formal roles. For example, if a teacher could not earn money informally they would have to leave the profession, as their formal income is not enough to live on. If senior citizens refused to engage in informal practices, then the state would be forced to confront questions on why pensions are so low and how corruption is allowed to impinge on the everyday of this group to such a large extent. This disengagement with the informal is obviously not going to occur as people need to operate in this manner in order to survive; thus, as Mitchell (2003) points out, the discourse of the dominance of the formal market economy remains unchallenged at a state level. Therefore, it can be argued that for many their informal practices are created as a result of exploitation. This is not explicit – for example, working in sweat-shop conditions – but a more subtle outcome of low wages and pensions. For many of a working age, their informal work has to take place in addition to their formal obligations, and obviously a great deal of time is devoted to work. This has serious implications for the household and for society in general as the following interviewees discuss:

During the ten years of the old government [the first two post-Soviet governments] people were hoping for better a life. But instead it became harder and harder. Everyone is now very stressed, be it about their children, the ecology or whether there will be another financial catastrophe. Even when having fun with friends it is not like it used to be as everyone is so stressed. Everyone is too busy ‘under-working’ so we can’t meet at the week-ends. Everyone has a lot of problems.

Many interviewees noted that they often experience feelings of humiliation at having to undertake so much extra work. As one interviewee said, also reinforcing the above point on the time factor of such tactics:

If you only work on one job the wage is not enough even to exist on. So we [the majority of workers] are forced to look for jobs on the side. It is like this! We have to go from extra work to extra work. This is how an ordinary worker lives, our wages are minimal. We have no privileges, only humiliation.

For senior citizens, while they have more time to undertake informal practices, these are often physically demanding and offer little long-term security. Most interviewees stated that it is extremely difficult to save considerable sums of money, and those engaged with domestic production can often only generate enough income to see them through the coming winter.

Yet many people take great pride in their informal practices. Many of the practices are extremely ingenious and would contribute greatly to the formal economy if the barriers to entry were lowered. The social capital which facilitates these processes also provides a security far beyond the economic. Many interviewees discussed how their social networks are built on deep levels of trust and thus individuals know that in a time of crisis they have people to turn to. As Lefebvre (2006: 171) argues ‘[d]aily life has served as a refuge from the tragic, and still does: above all else, people seek, and find, security there’. An extension of this is the importance of the spaces within which the processes take place. De Certeau (1988) talks at length, in an urban context, about how such networks, and use of space, extend the ‘living room’ of the household into the everyday spaces that surround them. For example, a small plot of land used for subsistence production might be seen as ‘backwards’ by the state, a brake on the development of the ‘market’, but it can be of crucial importance to those who use it, not just for the food it produces but for the spaces of resistance it provides to externally introduced marginalisation.

Furthermore, as De Certeau (1988: 108) says, in relation to how individuals use their neighbourhood and the networks within it, ‘“I feel good here”: the well-being under-expressed in the language it appears in like a fleeting glimmer is a spatial practice.’ Such sentiments clearly exist in the spaces that the above informal practices take place in and, to paraphrase de Certeau, many people further believe that ‘I can survive here.’ Thus, schemes which seek a geographical fix by encouraging the movement of economically marginalised groups to regions with lower living costs are doomed to failure as coping tactics are deeply entwined within the spaces they are taking place within (for an example of a failure of a scheme to move people out of the climatically inhospitable Russian north, see Round 2006). Therefore, the spaces informal practices take place across can be simultaneously sites of formal/informal processes, strategies/tactics, exploitation/resistance with the boundaries between them often blurred. With the state unwilling to engage with such complexity, preferring to reduce informal processes to a means of ‘cheating the state’, it is extremely difficult for them to develop policies which could truly impact positively on the everyday lives of Ukraine’s economically marginalised.

Prevalence and nature of informal employment in Moscow

Asking the 313 participants in the survey in Moscow what work is most important for securing their livelihood, along with what is second most important, the finding is that one in three (32 per cent) primarily rely on informal employment for their livelihood and a further one in nine (11 per cent) assert that informal employment is the second most important contributor. Some 43 per cent thus cite this sphere as either the principal or secondary means of securing a livelihood. As such, informal employment is again not a residue or leftover. It is a core livelihood practice, as previously identified elsewhere in post-Soviet societies (Wallace and Haerpfer 2002; Wallace and Latcheva 2006). Who undertakes such practices? Only 25 per cent of working-age households with nobody in formal employment cited informal employment as their primary strategy, but 40 per cent of households with one formal wage earner and 35 per cent of households with multiple declared wage earners. Indeed, of all households chiefly relying on informal employment, just 20 per cent had nobody in formal employment (22 per cent of all households surveyed), 25 per cent were multiple-earner households (35 per cent of households surveyed) and 55 per cent single-earner households (43 per cent). To portray informal employment as used by marginalised Muscovites excluded from the formal labour market is therefore erroneous.

There are, however, some major differences across the districts studied in terms of the dependence of the populations on informal employment. In the affluent west Moscow district of Krylatskoe and the deprived district in southeast Moscow, around one-quarter of households relied on informal employment as their primary means of livelihood (28 per cent and 24 per cent, respectively). In the mixed area of Leshkovo, however, where the affluent and ‘working poor’/state benefit-dependent live alongside each other, reliance on informal employment was higher with just under half (47 per cent) of households chiefly depending on such employment for their livelihood. In this district, such work is largely undertaken by lower-income groups who supply the rich Russians living alongside them with gardening services, baby-sitting, domestic cleaning and home repair and maintenance. This reinforces the finding of previous studies in western nations that higher levels of informal employment exist in districts with a mix of higher-and lower-income groups (Portes 1994; Williams and Winde-bank 1998). In consequence, informal employment is not some marginal sphere of minor importance to a limited range of households but, rather, is an important practice for a large proportion of the Moscow population, and this applies across all of the districts studied. Indeed, this centrality of informal employment becomes even more apparent when analysing the sources of labour households use to complete a range of common domestic service tasks. Analysing the source of labour last used by households to undertake common domestic tasks, the finding is that overall, 18.2 per cent were last completed using informal employment, and just 6.9 per cent using formal labour. In other words, in the domestic services sector, nearly three times more tasks are conducted using informal employment than are undertaken using formal labour.

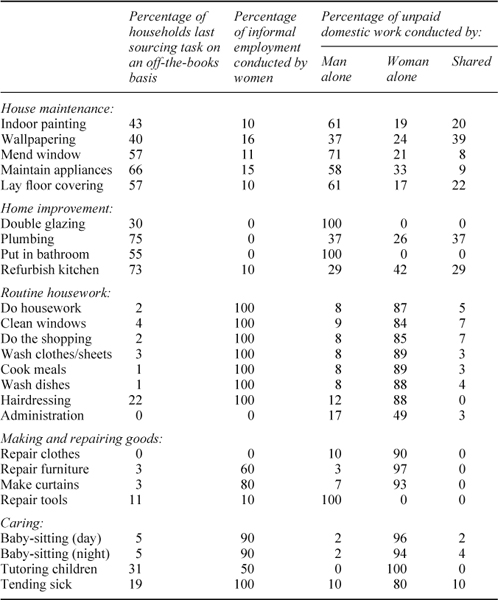

In what spheres is informal employment rife? Analysing the tasks in which the use of informal employment is most commonly used (see Table 6.6), the finding is that these are plumbing (which in 75.2 per cent of cases was last completed using off-the-books labour), bathroom refurbishment (72.9 per cent), appliance maintenance (66.2 per cent), floor laying (57.0 per cent), glazing (56.8 per cent), kitchen refurbishment (56.3 per cent), indoor painting (45.6 per cent), wallpapering (40.2 per cent), double-glazing installation (31.6 per cent), tutoring (31.3 per cent) and hairdressing (22.2 per cent). Analysing the ratios of informal to formal labour for each task, moreover, the magnitude of informal relative to formal labour can be evaluated for different tasks. Both washing dishes and domestic appliance repair are never conducted on a formal basis (the former displaying the total absence of formally employed domestic workers), while informal employment is 12 times the size of the formal economy in the sphere of plumbing, ten times the size in the realm of indoor painting, 7.7 times in the realm of glazing and 7.6 times for wallpapering.

It is also important to see how the gender divisions in the informal labour market reflect and reinforce the gender divisions of domestic labour. As Table 6.6 reveals, the tasks which women are most likely to conduct as informal employment mirror the tasks for which they are deemed to have responsibility when conducted as self-provisioning. Therefore, and akin to the formal labour market, the informal labour market mirrors the gender divisions found in the unpaid domestic realm.

Source: Moscow survey.

Why, therefore, do people engage in informal employment in Moscow? To evaluate this, first, consumers’ rationales are evaluated and, second, suppliers’ rationales. Examining consumers’ rationales, and as Table 6.7 displays, some 40 per cent of informal employment is used due to their lack of choice and/or exclusion from the formal economy, and a further 21 per cent included this issue in their explanation. Other consumers, however, use informal employment in preference to formal labour. Neo-liberals assert that this is because of the problems associated with sourcing declared goods and services, including the availability, quality and speed of the provision of legitimate goods and services. In this Moscow survey, some 26 per cent of informal employment was sourced purely for this reason and a further 24 per cent included this issue in their rationale. Post-structuralists, meanwhile, again assert that consumers use informal employment in preference to the formal economy, but explain this in terms of social or redistributive rationales. Some 8 per cent of informal employment was primarily to help someone and/or as a favour among friends, colleagues and acquaintances. A further 11 per cent included this issue in their explanation.

Table 6.7 Consumers’ motives for using informal employment in Moscow: by income level and location

Source: Moscow survey.

Consumers’ rationales, nevertheless, vary across populations. While ‘exclusion’ is more commonly cited among low-income households and those living in deprived neighbourhoods, ‘exit’ factors, particularly regarding poor formal provision, are more frequently cited among high-earners and those in affluent and rural areas. Social/redistributive rationales, meanwhile, are more frequently the chief rationale among higher-income households and affluent urban areas. Participation in informal employment for low-income groups and those in deprived areas is therefore more a result of exclusion, while it is more due to voluntary exit among high-income groups and those living in affluent areas. In consequence, different explanations are relevant to different groups.

Turning to suppliers’ rationales, Table 6.8 again differentiates those engaging in informal employment according to whether it is primarily due to their exclusion from the formal economy (e.g. because they could not find a regular job, the employer insisted on them being paid off-the-books or because there is no alternative) or a decision to exit the formal economy, and if so, whether this is due to problems faced working legitimately or for social/redistributive rationales. The finding is that 27 per cent of informal employment is explained purely in terms of exclusion from the formal economy, 50 per cent solely due to a desire to voluntarily exit the declared sphere, as argued by neo-liberal and post-structuralist commentators, and 23 per cent for a mix of both exit and exclusion rationales. Breaking down the decision to voluntarily exit the formal economy, 38 per cent of all informal employment was to avoid the costs, time and effort of formal registration and/or in preference to formal economy, and 12 per cent for social and/or redistributive reasons, such as a desire to help someone who is in need of help who would otherwise be unable to afford to get the work completed.

Source: Moscow survey.

Again, however, the rationales vary across population groups and areas. Voluntarism, and therefore the neo-liberal and post-structuralist explanations, is more commonly cited by those engaged in informal employment living in higher-income households, rural and affluent localities. Exclusion from the formal economy, meanwhile, is more common among low-income households and those living in urban and deprived areas. It is not just across different socio-economic and spatial populations, however, that variations exist in the reasons for participating in informal employment.

Breaking down informal employment into its component parts, the overarching finding is that 78 per cent is informal self-employment and the remaining 22 per cent is waged informal employment. The suggestion, therefore, is that in stark contrast to Ukraine, the vast majority of informal employment in Moscow is informal self-employment. Examining the reasons for participating in each of these different types, Table 6.9 reveals that some 51 per cent of waged informal employment is conducted for factors related to exclusion and 26 per cent for rationales associated with both exit and exclusion. Similarly, the desire to exit the legitimate realm is greater in own-account work, with those depicting participation more as a voluntary decision to exit the formal economy so as to avoid the costs, time and effort of formal registration, finding what they seek in informal self-employment (52 per cent of such endeavour is conducted for this reason).

Table 6.9 Relationship between type of informal employment and reasons for participation in Moscow

Source: Moscow survey.

It is important to be aware, however, that even if there is a close relationship between these different varieties of informal employment and the contrasting explanations, it is far from the case that all work in each category can be explained exclusively in terms of either exclusion or exit. To see this, each variety of informal employment is briefly reviewed in turn.

Informal waged employment in Moscow

In Moscow, 30 per cent of all informal waged employment is in wholly off-the-books enterprises. The majority (80 per cent) is in legitimate organisations. Moreover, although nearly two-thirds (60 per cent) of informal waged employment is conducted by men, women are more likely to work in informal waged employment for formal enterprises rather than for wholly informal enterprises; some 90 per cent of women in informal waged employment work in formal enterprises and 10 per cent for wholly informal enterprises. Meanwhile, just 75 per cent of men in waged informal employment work in formal enterprises and 25 per cent in wholly informal enterprises. This gender segmentation of the organisations in which men and women undertake informal waged employment is reflected in the type of work they undertake. Of all informal waged employment, 32 per cent is full-time work and mostly carried out by men in wholly informal enterprises on a temporary or occasional basis, while 68 per cent is part-time employment and conducted more by women on a regular basis. Informal waged employees are not just employed by businesses, but also by affluent Russian families (‘new Russians’) in the personal services sector. These informal employees are often senior citizens working as cleaners, baby-sitters, cooks and gardeners. In Moscow, the official average salary is 15,000 roubles (£300) per month, which is about what is required to get by. Although war veteran pensioners receive 10,000–15,000 roubles, all other pensioners receive 3,000–4,000 roubles (£60–80), which is slightly higher than elsewhere due to a supplement being paid by the Moscow government. This is insufficient for most to get by, so informal employment is sought. Participants spoke of exploitative working conditions in this personal services sector, including beatings and mistreatment by employers and failures to pay, mirroring the conditions for domestic servants elsewhere in the world (Cox 2006). It needs to be recognised, nevertheless, that this is but one segment of those engaged in waged informal employment, albeit one that portrays well the poor working conditions that can occur in this sphere.

Examining why people engage in waged informal employment, those engaged in such work are more likely to do so for reasons of exclusion (63 per cent) or for reasons of both exit and exclusion (23 per cent). Just 14 per cent do so for exit reasons. This is reflected in the fact that 70 per cent do not have formal jobs and such informal waged work is what Pfau-Effinger (2009) terms a ‘poverty-escape’ type in that it is their main source of income and largely done out of necessity. When conducted as what she terms the ‘moonlighting’ type, that is, on a temporary or part-time basis as a way of earning some additional income by those in formal jobs, then it is more often conducted primarily out of choice.

Informal self-employment in Moscow

In the 313 households interviewed comprising 702 adults, 102 engaged in self-employment. Of these, just 4 per cent had registered their business, although even these all conducted a portion of their trade informally. The remaining 96 per cent had not registered their enterprise, did not have a licence to trade on a self-employed basis and conducted all their transactions off-the-books. The only conclusion that can be reached, therefore, albeit from a small sample, is that the vast bulk of the self-employed in Moscow are not even on the radar of the state. Who, therefore, are these self-employed? The finding, akin to Ukraine, is that they are polarised at the two ends of the income spectrum. Some 56 per cent of the informal self-employed surveyed live in the highest quartile of households by gross household income and 30 per cent in the lowest income quartile. At both ends of the income spectrum, moreover, households heavily rely on the income from this informal self-employment as a means of livelihood. Just under two-thirds (61 per cent) of the informal self-employed living in the highest-income households assert that this is their primary source of livelihood, as do 68 per cent of those who have started up enterprises who live in the lowest-income households. For most informal self-employed, therefore, this is their prime source of income.

This, however, is where the similarities between higher-and lower-income households end. The type of informal self-employment conducted is very different. Those living in higher-income households often have a formal job and use their formal job to engage in relatively well-paid informal self-employment. An example is a husband and wife who are both school teachers and earn through their formal jobs about 6,000 roubles a month each. They then provide supplementary lessons on an off-the-books self-employed basis. Between them, they have four groups of ten children who each pay 200 roubles for a 1.5 hour lesson. Each gives three informal lessons per week, so they earn 24,000 roubles per week additional income. However, it is not just professional people using their formal employment to engage in informal self-employment. Often people keep their low-paid formal jobs because of the informal earnings they can make. An example is a 52-year-old cleaner at a meat processing plant who has a formal salary of 3,000 roubles per month. Each day, she collects up some 20 kg of ‘waste’ meat which is supposed to be thrown away, and has an agreement with the butchers that they will leave out good pieces for which she pays them 400 roubles per day. She sells the meat to a butcher at the market for 50 roubles per kilogram (1,000 roubles per day), who in turn sells it to customers for 220 roubles per kilogram. She therefore makes 600 roubles per day, or 12,000 per month, to supplement her 3,000 roubles formal salary.

Those in lower-income households, in stark contrast, often do not have a formal job that they can use to engage in informal self-employment. Instead, they are confined to lower-paid forms of informal self-employment. Indeed, all respondents interviewed in these households who engaged in informal self-employment asserted that they would prefer a ‘normal’ formal job so as to minimise their risks of being cheated, robbed and to be able to have paid leave, but did not have the opportunity to do so. Instead, they had to rely on piecemeal informal self-employment in order to raise sufficient income to survive. Examples are a pensioner who supplements her state pension of 2,200 roubles/month by selling cigarettes at a train station, an illegal street vendor who sells flowers which she grows on her dacha just outside a market, and a security guard at the block of flats where he himself lives who is paid by the formally employed security guard 10 per cent of his salary to provide 24-hour cover for him. On the whole, however, most informal self-employed are not officially classified as unemployed. Some 60 per cent have a formal job and operate their business alongside their formal waged work as an ‘on-the-side’ business venture. Most of these are concentrated in the higher-income brackets and depend on the income from their nascent enterprise as their prime source of income due to the relatively low level of earnings from their formal employment. The remaining 40 per cent are a mixture of various categories of people registered as non-employed, including the ‘economically inactive’ such as housewives and others unregistered as engaging in any form of employment, pensioners and people claiming unemployment benefit. These tend to be concentrated in the lowest household income bracket and to earn less from their informal self-employment.

Turning to the rationales for informal self-employment, meanwhile, similar findings are identified to Ukraine. Those in the lower-income populations are more likely to engage in informal self-employment out of necessity and those in higher-income populations more out of choice. Typical responses of the 45 per cent asserting that they primarily engaged in informal self-employment out of necessity so as to generate sufficient income to live or survive were ‘you cannot survive on state benefits, it doesn’t even pay for your food’; ‘if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have enough money to be able to survive’; ‘it was my only option’; and ‘I had no choice. I wanted to buy things like clothes for my children and food.’ Popular responses by the 25 per cent asserting that it was to increase their income, meanwhile, were ‘my official earnings are not enough to pay for anything else other than our housing and food bills’ and ‘I needed extra to be able to buy more than just the necessities.’ Unlike in other nations where necessity entrepreneurs might pursue such ventures due to a lack of formal employment opportunities, however, this was not the case in Moscow. Instead, the necessity to pursue such a venture is often borne out of the fact that the income provided by their formal employment or state benefits was inadequate to meet their daily needs. Akin to Ukraine, meanwhile, those doing so more out of choice often engage in informal self-employment either to avoid the costs, time and effort of formal registration, or for social and redistributive reasons.

In transition to the formal economy?

Do the informal self-employed view themselves as in transition to the formal economy? On the whole, less than 5 per cent regard themselves as likely to make the transition to becoming registered enterprises declaring their income for tax and social insurance purposes. The first reason for this is a lack of trust in the state to use taxes for purposes of public benefit. An example is a woman who runs a kindergarten from home. Responsible for a young preschool child, she looks after five other children whose parents pay 3,000 roubles per month for each child, meaning she earns 15,000 roubles a month, the official average Moscow salary. As she puts it,

I raise my granddaughter [her daughter had died giving birth], and raise her in good company. I thought about getting a licence at the very beginning. I would not be allowed. It is necessary to have special educational qualifications to apply for such a licence. Of course, you can always ‘buy’ a licence but I do not think I should do it. What for? My group is very small and I earn just enough to make a living… . Also, I think that paying 13 per cent tax out of my small income would be unfair. Besides, I am not even sure that the state is able to use our taxes properly. They did not pay for the health care to save my daughter.

This lack of trust in the state to use taxes to provide public services was the most common rationale given in 66 per cent of cases by these self-employed for not registering their business. The second most common reason, stated by 60 per cent, was the difficulties encountered when attempting to register a business and pay taxes. A self-employed decorator/builder neatly summed up the attitude of many we interviewed:

Why become formal? It is too much hassle and my business is very small and it will never grow that much bigger. The whole operation is cash in hand – suppliers want paying in cash and customers want the price as cheap as possible. If I need extra labour I have plenty of people I can call and pay cash for a few days’ work. There is just no logic to formalising as if I did I would have to pay a lot of tax and spends days filling out paperwork. It is better just to keep small, earn a decent income and keep out of view from the authorities.

In this Moscow survey, in sum, informal employment is a work practice widely used as a primary tactic for securing a livelihood. There are, nevertheless, differences in the reasons for engaging in such a practice according to both the type of informal employment conducted and the situation of the household. Those engaged in waged informal employment are more likely to do so out of necessity, while those engaged in informal self-employment are more likely to do so out of choice. On the whole, moreover, lower-income populations tend to engage in informal employment more out of necessity and higher-income populations out of choice. Such generalisations, however, should be treated with caution since there are many variations both within each population group and across each type of informal employment.

This chapter has revealed that informal employment in post-Soviet/socialist economies is not some small residue that is steadily disappearing from view. According to one popular indirect measurement method, its magnitude is equivalent to 32.6 per cent of GDP across post-Soviet/socialist economies and although it has declined slightly over the last few years relative to the formal economy, it remains a sizeable feature across all post-Soviet/socialist societies. Indeed, examining the results of the surveys conducted in Ukraine and Moscow, this chapter has revealed that informal employment plays a central role in the livelihood practices of a large proportion of households. Indeed, some 40 per cent of Ukrainian households cite informal employment as either the principal or secondary contributor to their living standard and 43 per cent in Moscow.

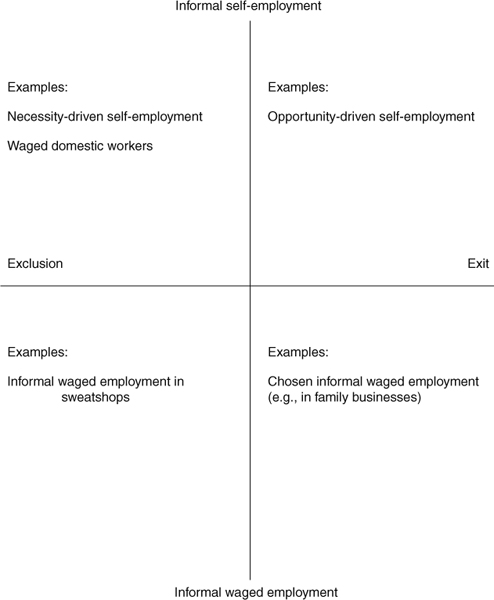

Examining their reasons for engaging in informal employment, moreover, in Ukraine, 30 per cent of informal employment is explained purely in terms of exclusion from the formal economy, 35 per cent purely to avoid the costs, time and effort of formal registration and in preference to formal employment, and 13 per cent purely for social and/or redistributive reasons, with the remaining 22 per cent a mix of these rationales. Similar levels of reliance on informal employment and diversity in the rationales among those engaged in informal employment was identified in Moscow. Despite this heavy reliance on informal employment in both countries and similar rationales being expressed for engaging in this work, the configuration of informal employment differs markedly across the two countries. The finding is that in Moscow, 78 per cent is informal self-employment and 22 per cent is waged informal employment. In Ukraine, in contrast, 38 per cent is informal self-employment and 62 per cent waged informal employment. Yet despite this, the rationales for engagement in each type of informal employment and by each population group are markedly similar in both countries. Voluntarism, and therefore the neo-liberal and post-structuralist explanations, is more commonly cited by those engaged in informal self-employment and those living in higher-income households, rural and affluent localities. Exclusion from the formal economy, meanwhile, is more commonly cited among those engaged in waged informal employment and among low-income households, and those living in urban and deprived areas, as summarised in Figure 6.3.

It is important to be aware, however, that even if some types of explanation are more common for some types of informal employment than others, there remains tremendous diversity in the rationales for participating in each type of informal employment among different population groups. In other words, there is a rich tapestry of both types of informal employment and reasons for engaging in them in these post-Soviet/socialist societies that cannot be neatly captured by promulgating universal hues. Just as one would not draw universal generalisations about formal waged employment and formal self-employment when evaluating its nature or the reasons for engaging in such work, it is similarly erroneous to do so when considering the informal labour market in post-Soviet/socialist societies.