Charitable Giving

James Andreoni* and A. Abigail Payne†, *University of California, San Diego, USA, †McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

Abstract

This Chapter summarizes the overall facts about charitable giving. Charitable giving has remained an active and important area within Public Economics. Then also discusses about the four main approaches one could take to research on charitable giving. The first approach is to look at giving as a simple individual economic decision, where a quantity of gifts to supply is determined by maximizing a utility function subject to a budget constraint. The second approach is to think of giving as a strategic interaction, with many actors involved. The third and potentially very fruitful approach based on giving as a social exchange. The request may come from a friend, a co-worker, a door-to-door solicitor, a phone call from a fund drive, an on-air campaign from public broadcasting, a television commercial with an emotional appeal, or even from a news report during a time of a disaster. Finally, the fourth and newest approach: giving as a response to conscious, or perhaps even unconscious, empathic, moral, or cultural urges.

Keywords

Fundraising; Taxable income; Taxpayer; Endowment; Leadership gifts; Social welfare; Peer pressure; Matching illusion

1 Introduction

Charitable giving has remained an active and important area within Public Economics since researchers like Martin Feldstein and coauthors published some of the first policy studies on the topic in the 1970s.1 Today, our knowledge on charitable giving draws from important research in applied econometrics, economic theory, game theory, and experimental and behavioral economics.

The applied econometrician, looking either at individual tax returns, survey data, or tax returns of the charities themselves, is interested in how economic variables influence or are correlated with giving. Do givers respond to tax incentives? How does giving change with income? How do receipts of charities vary with dollars spent on fundraising? Do government grants to charities affect the dollars raised by charities and through what mechanism?

The economic theorist is confronted with the issue of what form preferences take. Since charities have primary properties that are similar to public goods, a natural model of charities is as a privately provided public good. However, free riding provides a strong incentive in these models, leading to predictions of very little giving. But most households give something to charity each year, and in many countries average giving is a significant fraction of income—nearly 2% in the US, for instance. This would indicate that motives other than a pure interest in charitable output itself are involved in the decision to give. Unfortunately, these other motives are difficult to detect in survey or tax return data.

With this quandary as a backdrop, much of the recent theoretical, experimental, and behavioral research on giving has focused on identifying the underlying motives. Careful thinking on the theoretical side is necessary to generate hypotheses that can be confronted with data. Since naturally occurring data often lacks the specificity to test theories, data must at times be collected under some experimental control, either in the laboratory or in the field. This branch of the literature on charitable giving is the source of some of the greatest insights and the greatest promise and, in recent years, greatest growth in research.

Once one has a better handle on the underlying preferences for giving, the theorist can begin to tackle broader issues regarding policy toward charitable giving. How does the charitable sector overcome the free rider problem? What are the strategic responses in the market for giving among all the players? Does competition among charities spark efficient innovation or wasteful fundraising? What is the optimal tax policy toward charitable giving, and how can it take advantage of these naturally occurring preferences and institutions to maximize efficiency?

The importance and popularity of research on charitable giving is evidenced by a number of recent review articles. Andreoni (2006b) provides a lengthy summary of research from the prior 25 years of study. List (2011) gives a cogent account of innovations in the study of charity markets since 2006, and in between numerous other chapters and reviews have also appeared.2 Given the availability of other summaries of findings in the literature, this Handbook chapter will be more thematic, programmatic, and prescriptive than what is common for chapters of its type. Certainly we will highlight the main contributions since 2006, but we will use these to construct a lattice for how we think future work in the area would be most informative and productive, highlighting unpublished as well as published works. We hope to provide the new reader with a perspective on the current state of the literature, and for the experienced reader, we hope to point to new and important questions that remain unanswered.

The next section will give a brief summary of the overall facts about charitable giving, in the US and internationally. This will lay out the main facts to be explained or captured in the research. We will then discuss four main approaches one could take to research on charitable giving, highlighting the primary questions and limitations of each approach. Of course, all approaches have value and none in isolation can answer every question.

The first approach is to look at giving as a simple individual economic decision, where a quantity of gifts to supply is determined by maximizing a utility function subject to a budget constraint. This is a natural place to begin and allows an easy framework for approaching simple survey data from individuals, and for identifying simple and important policy goals.

The second approach is to think of giving as a strategic interaction, with many actors involved. This market view of giving suggests that donors are choosing gifts, charities are choosing fundraising efforts and mechanisms, and if the government is involved it is choosing grants to charities and subsidies to donors.3 A fourth player may also be at work: charitable foundations. Foundations are a kind of charitable intermediary. They collect contributions, often qualifying the donor for a tax benefit, and only later spend these dollars on the “end producer” of the charitable goods and services. All four of these types of participants can be acting in response to the choices of the others. We will discuss new theoretical and empirical studies that take account of these interdependencies.

Recently scholars have added a third and potentially very fruitful approach based on giving as a social exchange. In particular, a charitable contribution is rarely made in the absence of an overt request to give. The request may come from a friend, a co-worker, a door-to-door solicitor, a phone call from a fund drive, an on-air campaign from public broadcasting, a television commercial with an emotional appeal, or even from a news report during a time of a disaster. Moreover, when giving is to some degree visible by others, it complicates the social interaction with a league of new influences. What, for example, will someone watching infer about a giver’s character? The important thing about social interactions is that they are likely to be central to understanding changes in giving. While once one becomes a giver, simply answering annual appeals may be a way of “planning” responsible degrees of altruism, if we are to discuss what affects a change in giving, we will need to address the question, “What makes one become a giver in the first place?” The inherent sociality of giving, we conjecture, will be a part of this answer.

This leads naturally to the fourth and newest approach: giving as a response to conscious, or perhaps even unconscious, empathic, moral, or cultural urges. These are the kinds of urges that psychologists, biologists, and anthropologists tell us distinguish humans from most other animals. We tend to have heightened senses of empathy, we are governed more by internal—yet socially agreed upon—notions of justice, and we are concerned with the moral impressions we leave with neighbors and acquaintances. These are all true even though, as a species, we are far removed from the environments that likely implanted these values in our psyche: competing for survival in small communities of clan and kin. Understanding how these pressures are presented today, we conjecture, will be key to the next generation of research on altruism, giving, fundraising, and markets for charity.

How does all this research feed into prescriptions for policy? Historically, there have been two main policy questions regarding charity: What is the price elasticity of giving, and do government grants crowd out private donations? While these questions remain relevant today, recent work has broadened the kinds of policy issues economists face. Most central to these are issues related to fundraising and institutional design. For instance, scientific research can be supported through government taxation and grants to scientists by institutions like the National Science Foundation, or through private foundations that mimic the NSF but are funded through tax-deductable donations. One requires distortionary taxes to fund, while the other may create deadweight loss through the costs of fundraising. The incidence of the two is also quite different—those with high demand pay more under private provision, but their preferences are also more heavily weighted than low demanders. The more we understand these social and financial costs of fundraising, the more we can say about how best to organize society to provide needed social goods.

A related pedagogical issue arises about fundraising. Many studies and experiments help us to understand why people give and what triggers a gift. While this helps us understand foundational economic questions, such as the psychic costs of saying “no” to a fundraiser, it also often yields information that can help fundraisers increase donations. There are two delicate issues here that economic research has yet to debate. First, one must resist the inference that anything that increases donations is good for society. The role of the public economist has always been to find the greatest good for the greatest number, and fundraising for charity is just one of many institutional forms for supporting these goods that are available to society. Second, do we as economists have an obligation or even an interest in uncovering new methods that help charities raise more dollars? We don’t study how for-profits could improve revenues, so if the objective of a study is to find better fundraising methods for non-profits then it is incumbent upon the scientist to argue that it is in the social interest to do so.

2 Background: Facts and Figures on Charitable Giving

Here we summarize the within and between country differences in charitable giving. This seemingly straightforward task is, unfortunately, difficult to accomplish, as data sources vary in the frequency and methods of their collection, and in the fidelity of the reports. Nonetheless we make our best attempt to characterize the general facts about giving.4

Looking at giving as a percent of GDP in 2005, Charities Aid Foundation (2006) ranked the US highest (1.67%), followed by the UK (0.73%), Canada (0.72%), Australia (0.69%), and South Africa (0.64%).5 At the lower end of the scale were France (0.14%), Germany (0.22%), and Turkey (0.23%). These numbers, however, are based on values of reported donations by individuals. This is but a partial picture of philanthropy. Philanthropy also encompasses donating time, helping a stranger, participating in a community event, and even helping one’s family members. Creating measures that compare giving across countries is difficult if countries and/or cultures value these types of giving differently. Depending on the method used to measure giving, which country is more generous will vary. For example, consider the World Giving Index developed by the UK Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) using world survey data collected by the Gallup organization. The index is based on surveys of 150,000 individuals from 153 countries. The following three questions formed the basis of the index: In the month prior to the survey being complete6: (i) Have you donated money to a charity? (ii) Have you volunteered your time to an organization? (iii) Have you helped a stranger or someone you did not know who needed help?

Based on the responses to these questions, CAF assigned to each country a number to reflect their level of giving behavior for 2010 and 2011. As with any survey, however, there are many possible avenues for inaccuracies, and indeed there is a great variation in the index across these 2 years. For example, in 2010 the US ranked fifth in overall giving; in 2011, the US ranked first. The top countries for giving money include Thailand, the UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Morocco, Australia, Iceland, and Malta (the US in 2011 was tied for tenth place). Georgia, Russia, Madagascar, and Cote d’Ivoire are at the bottom. The top countries for volunteering are Turkmenistan, Liberia, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, the US (fifth place), Guinea, Nigeria, Philippines, Uzbekistan, and Myanmar. Greece, Serbia, Croatia, and China are at the bottom. And the top countries for helping a stranger include Liberia, the US (2nd), Ghana, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan, New Zealand, Qatar, and Australia. Madagascar, Rwanda, Burundi, Albania, Indonesia, and Japan are at the bottom.

These statistics illustrate that giving and perceptions about giving vary across the world. They also illustrate that there is no single measure that fully captures generosity or giving.

Next we ask, how has giving changed over time? Let us start by looking at data for the United States. Our numbers are drawn from the annual publication, Giving USA 2012. The analysts for this publication draw their data from several sources and then apply an econometric model to estimate how the general population behaves. This is necessary because there is no single source for identifying either individual donations to charity or the recipients of the donations. For example, reported giving on tax returns only identifies the giving of those with taxable income who itemize. Charity tax returns are only required by organizations that meet a minimum threshold for income and are not religious. Given there is no single source that allows us to measure giving and the charity recipients of the gifts in the US, the figures in the Giving USA 2012 publication represent the best guesses of trained analysts.

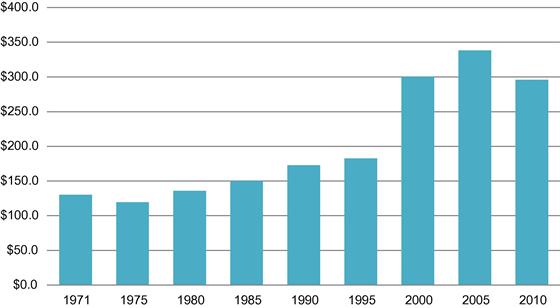

In 2010, total contributions to charity by individuals, corporations, foundations, and through bequests were estimated at nearly $296 billion in the US, an increase of approximately 2% over the previous year after adjusting for inflation. The increase in 2010 over 2009, however, came after a 2-year decline in giving. Over the last four decades (1970–2010) the biggest increase in real growth occurred in the late 1990s and again around 2007. These patterns are shown in Figure 1. Giving by individuals as a share of their disposable income has varied over the period but for the most part has hovered around 2% (minimum of 1.7% in the early 1990s; maximum of 2.4% in the mid-2000s). While a high percentage of individuals give to charity today, there is great variance in the levels of giving. Many people give a small amount and a few people give a large amount. There is also variation in the types of charities to which individuals give. For example, as will be shown below, the largest recipient of charitable donations are religious organizations. These gifts come largely from lower income individuals. If one studies individuals that gave more than $1 million, their gifts go mostly to education and health-related organizations.7

Figure 1 Annual giving by private sources, 1970–2010 $ billions (real, base year 2011). (Source: Giving USA 2012: The annual report on Philanthropy, giving USA.)

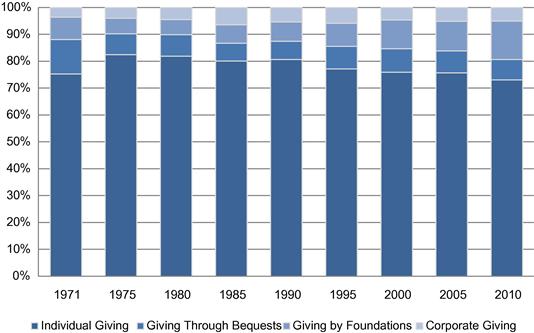

In Figure 2, we show the share of private giving by type across four groups: individual giving, giving through bequests, giving by foundations, and corporate giving. The striking phenomenon is that the share of giving from private individuals has declined and the share of giving by foundations has increased over time. While the data currently available make it difficult to understand this trend, there is a sense that the growth in foundation giving may be attributable to a growth in giving by higher wealth individuals who choose to first direct their giving to a foundation and then to use the foundation as a vehicle for giving to charities.

Figure 2 Share of private giving, by type of donor, 1970–2010. (Source: Giving USA 2012: The annual report on Philanthropy, giving USA.)

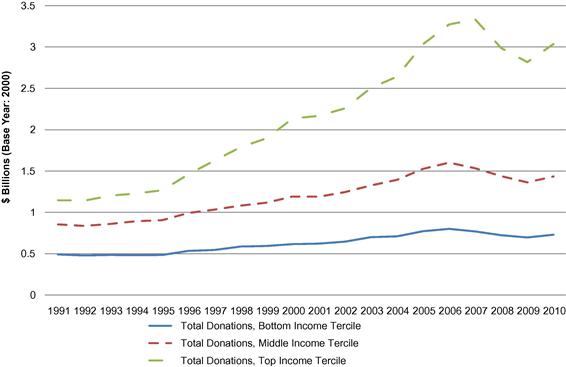

The above figures are similar to those observed in other countries, especially Canada and the UK. Using tax returns filed in Canada by individuals that reside in urban areas, we can depict the level of giving across neighborhood types defined by the average household income for the neighborhood (defining a neighborhood as a postal code area that covers approximately 5000–8000 households). Figure 3 depicts the total reported charitable giving by individuals for neighborhoods broken down into income terciles. Giving by those living in higher income neighborhoods has grown much faster in the 1990s and early 2000s than for the other two groups.

Figure 3 Reported tax receipted gifts in Canada by neighborhood income grouping. (Source: Data at neighborhood level for reported giving on individual tax returns, statistics Canada, as modified by public economics data analysis laboratory, McMaster University, 2012.)

Notice that Figures 2 and 3 are pointing to an interesting pattern. Giving is becoming increasingly concentrated with the wealthy, either through individual giving or from foundations. In the US, the number of foundations increased by 54% between 1999 and 2009, to over 120,000 (National Center for Charitable Statistics, 2011, Nonprofit Sector in Brief: Public Charities, Giving, and Volunteering). In Canada, foundations grew by 74% between 1992 and 2008, from 5400 to 9400. This raises interesting questions about the influence of foundations on giving by others and in promoting the stability of the charitable sector.

While tax laws impose some requirements around the distribution of funding, foundations are able to harbor their endowments well into the future. They have flexibility in how they use their funds intertemporally, and in how they target funding to support certain types of charitable activities. Increasingly, however, we are observing foundations taking on a bigger policy role in that they can influence charity activity and can use their funds to leverage donor behavior. One example of this leverage is the lead that has been taken by the Gates Foundation to focus on big issues (e.g., eradication of polio, fixing the public educational system) and to encourage others to match their funding. For example, the Gates Foundation teamed up with Rotary International and encouraged Rotary groups all over the world to raise funds in support of eradicating polio.

In a broader context, foundations and well-positioned individuals can influence charitable giving. An example of the dynamics of using wealth and/or prestige to influence giving is found in the activities being undertaken by the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI). While CGI is not an organization to which individuals can donate, it views itself at the “eBay of philanthropy, bringing together buyers and sellers in the world of giving.” (“How Clinton Changed Philanthropy,” Time Magazine, October 1, 2012, page 32). The CGI seeks to influence giving by promoting philanthropic policies and raising awareness of issues that can affect the decisions of donors about what causes to support. The CGI is an example of how social networking by influential individuals (versus direct donations) can affect the growth of certain charities and the direction of charitable giving in a significant way.

If wealth that supports charities is held in the hands of a few, this can create a greater divide between charities with significant assets and those with virtually none. Despite the large numbers of charities in the US and elsewhere, most charities operate on very small budgets and have few if any assets. In 2010, for instance, 16.5% of charities reported total expenditures greater than $1 million; 45% of charities reported expenditures less than $100,000. These statistics exclude the very small charities (Urban Institute, The Nonprofit Sector in Brief: Public Charities, Giving, and Volunteering, 2012). If tax policy promotes giving by those with higher incomes and greater wealth, then it is important to understand how these policies affect charity operations. For instance, if donors with greater wealth support bigger charities, then we will observe a greater divide between charities with and without sufficient capital to operate. This hypothesis would hold up if there is a strong correlation between the wealth of the benefactors and charity size.

While most charities would not begrudge funding from any donor, if charities are reliant on a few major donors, this places them in a vulnerable position. For example, if the few donors change preferences or change their behavior with external events (like changes in the economy, or natural disasters) this could cause gifts to swing across charities, making the charities too vulnerable in the whims of their financiers.

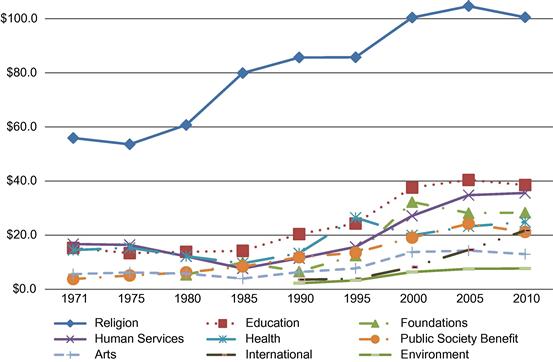

Who are the recipients of these contributions? In 2010 there were close to 1.3 million 501(c)(3) organizations in the US—this excludes churches, nonprofits, and social enterprises. In the last decade, the number of charities has grown by close to 59% (from 632,000 in 1999). Other types of nonprofits, those classified as 501(c) but not 501(c)(3), experienced very little growth (approximately 3%).8 The types of nonprofits that benefit the most from private giving are those in the area of religion, which accounts for 35% of the total contributions. Educational organizations are the second biggest recipient (14%), followed by foundations (11%), human services (9%), health (8%), and public-society (8%). Contributions to other types of charities (arts, international affairs, environment, and animal-related organizations) accounted for less than 5% of private giving. Figure 4 illustrates these differences and the growth in giving by charity type for US charities between 1970 and 2010.

Figure 4 Total private giving by charity classification, $ billions (2011 base year). (Source: Giving USA 2012: The annual report on Philanthropy, giving USA.)

Figure 4 illustrates that religious giving dominates other forms and, perhaps, should be analyzed separately from other types of giving. For example, do individual donations to churches respond to tax incentives the same as other forms of giving? The figure also illustrates difference in the contributions and growth (or lack thereof) in contributions across sectors, demonstrating that one might want to explore these sectors separately when studying the impacts of tax and other policies. Second is the growth foundation giving. In 1980 this was the smallest of the categories, but by 2010 it was the third largest category, just below gifts to education-based charities.9 We will return to these and other issues throughout the discussion below.

3 Approach 1: Individuals

We begin this section by briefly reviewing what we have learned through controlled experiments and how this helps to better frame a characterization of preferences. We then turn to econometric applications of this approach to data on individuals.

3.1 Preferences for Giving

Consider an individual i with post-tax income ![]() who consumes a composite private numeraire good

who consumes a composite private numeraire good ![]() and gives

and gives ![]() dollars to charity. With n individuals, let

dollars to charity. With n individuals, let ![]() be the total contributions to the charity. If individuals gain utility from only the final output of the charity, sometimes called pure altruism (Andreoni 1989), then G is a public good. The natural first model, therefore, is to assume preferences

be the total contributions to the charity. If individuals gain utility from only the final output of the charity, sometimes called pure altruism (Andreoni 1989), then G is a public good. The natural first model, therefore, is to assume preferences ![]() . As shown by Bergstrom, Blume, and Varian (1986) and Andreoni (1988), such a model leads to many absurd conclusions, including that only a sliver of the population should be contributors to the charity. Hence, any model that is going to capture the empirical findings is likely going to require that individuals, through some means, experience greater utility from their own contributions than those of others, that is,

. As shown by Bergstrom, Blume, and Varian (1986) and Andreoni (1988), such a model leads to many absurd conclusions, including that only a sliver of the population should be contributors to the charity. Hence, any model that is going to capture the empirical findings is likely going to require that individuals, through some means, experience greater utility from their own contributions than those of others, that is, ![]() , where utility is increasing in the third argument.10 This impure altruism was (somewhat pejoratively) dubbed warm-glow giving by Andreoni (1989, 1990).11

, where utility is increasing in the third argument.10 This impure altruism was (somewhat pejoratively) dubbed warm-glow giving by Andreoni (1989, 1990).11

Evidence for a warm-glow has come from many quarters. Laboratory experiments find responses to manipulations that most often support a basic “joy of giving” explanation. A laboratory experiment by Crumpler and Grossman (2008) showed that 57% of subjects made a contribution to charity, even though the contribution had no impact on the dollars received by the charity, but only on the composition of the dollars given—the subjects’ contributions completely displaced the experimenter’s contribution. This strongly supports a warm-glow. Tonin and Vlassopoulos (2010) look for a warm-glow in a real-effort field experiment on pro-social behavior. Using a manipulation similar to that of Crumpler and Grossman, these authors tell subjects that a charity will get ![]() regardless of the subject’s actions, but that the more effort the subject chooses the more of this

regardless of the subject’s actions, but that the more effort the subject chooses the more of this ![]() will be credited to the subject. They find that this manipulation creates a significant increase in effort. Many other laboratory tests find similar patterns in which own and others’ contributions are not perfect substitutes, as the warm-glow hypothesis requires.12 Konow (2010) develops a model of warm-glow that is founded on affective (emotional) states. He shows in theory and experiments that not all giving is the same—those gifts connected with a greater sense of need or deservingness also create more warm feelings. In a theme we will return to when discussing the fourth approach, giving and the utility of the warm-glow depends critically on the context, the need, and the impact of one’s donation. That is, the utility of the warm-glow is not separate from the altruistic concern one has for the recipient.

will be credited to the subject. They find that this manipulation creates a significant increase in effort. Many other laboratory tests find similar patterns in which own and others’ contributions are not perfect substitutes, as the warm-glow hypothesis requires.12 Konow (2010) develops a model of warm-glow that is founded on affective (emotional) states. He shows in theory and experiments that not all giving is the same—those gifts connected with a greater sense of need or deservingness also create more warm feelings. In a theme we will return to when discussing the fourth approach, giving and the utility of the warm-glow depends critically on the context, the need, and the impact of one’s donation. That is, the utility of the warm-glow is not separate from the altruistic concern one has for the recipient.

Perhaps the most convincing and provocative evidence for warm-glow comes from the neuroeconomics experiments done by Harbaugh, Mayr, and Burghart, published in Science in 2007. Subjects were told that some of their payment fee of $100 would be donated to charity involuntarily in some cases, as in the case for taxation, or only if they approved in other cases. Even though the outcome for the charity was the same in both scenarios, the subjects’ brains reflected significantly greater pleasure when the choice was made voluntarily. The effect was shown within subjects. A surprising finding, however, is that subjects preferred larger donations to smaller ones, even when they were made involuntarily. That is, people enjoy giving through taxation or voluntarily, but they enjoy the latter the most. This is precisely the foundational assumption of the model of warm-glow giving.

3.2 Analysis of Data on Individual Givers

One way of encouraging giving is to lower its price. Many countries provide some form of an income tax credit or deduction for giving. In the United States, for example, tax filers who itemize deductions may claim charitable donations as a deduction against taxable income. With a marginal tax rate of t, this creates a price of 1−t, that is, a gift g only costs the giver (1−t)g out-of-pocket. This has led to a surfeit of research measuring the compensated elasticity of giving, effectively asking the question, if there is a 1% change in price, 1−t, how responsive is giving, g. Bakija and Heim (2011) summarize this research and provide the most recent estimates of the price elasticity using a panel data set of individual tax returns spanning the period 1979–2006. Much of the research they report suggests the elasticity of giving, ![]() , is close to −1. A few find an inelastic response,

, is close to −1. A few find an inelastic response, ![]() , and Bakija and Heim suggest giving may most likely be elastic,

, and Bakija and Heim suggest giving may most likely be elastic, ![]() .

.

There is more to understanding how tax policies affect giving than simply trying to measure a price elasticity for giving. Across countries, there are a variety of schemes in place to provide individuals incentives to donate. In some countries (e.g., Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Switzerland) some or all individuals are obligated to donate as the laws require a fixed percentage of individual taxes be allocated to churches or other charities.13 With respect to voluntary donations, some countries provide direct incentives to all taxpayers (e.g., the US, Canada, the UK, Germany, Australia, India, Indonesia), others only to those with high incomes or high levels of donations, some strictly limit how much one can offset tax liability with her donation (e.g., Argentina [limited to 5% of taxable base], China [up to 30% of taxable income], Czech Republic [limit of 10% of income if at least 2% is donated], France [limit of 20% of taxable income], Russia [limit of 25% of taxable income], South Africa [limit of 10% of taxable income]), and others provide no incentives (e.g., Afghanistan, Brazil, Croatia, Israel [incentives given only for donations to public institutions]).

In recent decades, many of the changes in tax policies related to charitable giving provide greater incentives for wealthier individuals to donate. For example, in Australia donations of more than $5000 (AUD) receive a more advantageous tax treatment than donations of lesser amounts. In Germany, while donations are limited to 20% of income, an individual can deduct up to $1 million Euros if the donation is for the endowment of a foundation. In the US and Canada, donations of publicly traded securities and other property such as ecologically sensitive land have a lower effective price of giving than a cash donation of the same value. The reason for this is that the donor is allowed to take a charitable deduction against taxable earned income for the fair market value and not incur any capital gains on the difference between the fair market value and the basis of the securities or property. These changes may help to explain the growth in donations to foundations and faster growth in giving by individuals in higher income tax brackets. In Canada, for instance, a high proportion of foundations report receiving gifts of publicly traded securities. An extremely low proportion of registered charities, by contrast, report gifts of publicly traded securities. Very little work, however, has been done to explore the impacts of these policies on the price elasticity of giving, on the substitution between donations of cash and publicly traded securities, or the growing divergences in giving between higher and lower income individuals.

What if tax policy did not benefit the taxpayer but benefited the charity? For most taxpayers this is exactly what happens in the United Kingdom. Taxpayers receive neither a tax credit nor a deduction, unless they are high earners. Instead a system called “Gift Aid” is used. When an individual donates to a charity and identifies herself as a UK taxpayer, the charity can receive from the UK government the equivalent of the credit that the taxpayer would receive. For every pound donated, a charity can claim from the UK government a match that is based on the lowest tax rate for individuals (20%). Effectively this means that the charity can receive ![]() for every

for every ![]() donated (tax price is

donated (tax price is ![]() ). The exception to this system is for high income taxpayers. If they complete a form, they can receive a tax credit for their donations. Effectively this means that for every pound donated by a high rate taxpayer the price is

). The exception to this system is for high income taxpayers. If they complete a form, they can receive a tax credit for their donations. Effectively this means that for every pound donated by a high rate taxpayer the price is ![]() . Scharf and Smith (2010) explore whether high rate taxpayers giving differs across the scheme whereby the charity receives an amount equivalent to the credit and the scheme whereby the taxpayer receives the credit. If individuals understand the relationship, the government disbursement of revenues (in the system where charities receive the credit) is equivalent to receiving a tax credit on a reported donation to the government, then both systems should yield the same results. In the context of a survey of known high rate taxpayers that are donors, they randomly assigned questions about an increase in tax incentives (in the form of gift aid or in the form of a direct tax credit) to the donors. They find, despite the equivalence financially, that donors are likely to respond more positively to an increase in the gift aid amount than to an increase in the direct tax credit.

. Scharf and Smith (2010) explore whether high rate taxpayers giving differs across the scheme whereby the charity receives an amount equivalent to the credit and the scheme whereby the taxpayer receives the credit. If individuals understand the relationship, the government disbursement of revenues (in the system where charities receive the credit) is equivalent to receiving a tax credit on a reported donation to the government, then both systems should yield the same results. In the context of a survey of known high rate taxpayers that are donors, they randomly assigned questions about an increase in tax incentives (in the form of gift aid or in the form of a direct tax credit) to the donors. They find, despite the equivalence financially, that donors are likely to respond more positively to an increase in the gift aid amount than to an increase in the direct tax credit.

3.3 Households as Decision Makers

The analysis to this point has made the simplifying assumption that charitable decisions are made by individuals. In many cases, however, giving will be made by households. If men and women have different tastes about giving—or about the opportunity costs of giving—this presents a more complex and interesting question about how households resolve this conflict.

One could imagine a number of scenarios about how couples treat giving differently than individuals. For instance, if the couple shares the same tastes, then charitable giving could be seen as an enjoyable joint activity that couples do together. This could make couples give more to charity than individuals, and do so together. However, suppose that the couple disagrees either about the size or type of gifts. For example, one wants to support the homeless while the other prefers the opera. This might result in the couples bargaining with each other but making donation decisions jointly that effectively monitors or reins in each other’s spending. Another alternative is that one spouse may have stronger feelings about charity, better information, stronger social reasons (like giving at work), or lower transactions costs (like payroll deductions) that lead spouses to a delegate giving to one spouse. Finally, imagine a household where spouses keep separate finances. These spouses are likely to make independent decisions on giving.14

Two papers have explored these questions and come to many similar, but several importantly different conclusions. Andreoni, Brown, and Rischall (2003) use a question on the 1992 and 1994 Survey of Giving and Volunteering (SGV) in the United States that asked, “Who in your household is considered most involved in deciding which charities your household will give to?” The answers could be the respondent, spouse, or both. Yörük (2010) replicates this study, instead using the 2002 wave of the Center on Philanthropy Panel Study (COPPS), the Philanthropy Module of the PSID. This survey asks, “Who in your family was involved in decisions about how much support to give individual charities in 2002?” The answer could be the husband, wife, decide together, or decide separately. Thus the category, “both” from the SGV is more finely separated into “decide together” and “decide separately.” The two surveys differ in other important ways. While respondents have similar mean ages, the COPPS survey was taken 8–10 years later than the SGV survey, thus shifting the mix of marital cohorts. This shows up in other areas. The COPPS respondents have more education; there are about 7.7% points greater likelihood of being a college graduate among men, and about 6% points among women. Perhaps the biggest difference is that in the SGV data the likelihood that the husband is the primary earner is about 90%, while in the COPPS data the partnerships show more parity, with only about 60% of households having male as primary earners. If households are bargaining, therefore, one would expect more equal bargaining power in the COPPS than the SGV. This is exactly what is observed.

Adjusting for observables, both studies show little to no differences in amounts given by single males and females, but both show significant differences in the number of causes supported. Women appear to prefer giving less to more causes, while men prefer to specialize in one or two causes. Male deciders were also more sensitive to price in both data sets, especially when the price was low.15 In the SGV data, when both spouses decide (which could include both deciding together and independently), the analysis shows that households give about 6% less than had they each decided unilaterally and, moreover, the husband was estimated to have the dominant bargaining power, with his preferences getting more than twice the weight given to hers.16 COPPS data, by contrast, showed that couples deciding jointly (but not independently) actually gave 7% more than one would predict if they acted unilaterally. Moreover, bargaining power was nearly identical between spouses, with the wives estimated to actually have a bit more leverage than their husbands.

The degree of similarity between the two studies of Andreoni, Brown, and Rischall (2003) and Yörük (2010) tends to make the differences between the two all the more fascinating.17 Could it be that the differences in household bargaining could be due to cohort effects as more progressive values are represented in the newer data, and that these households are more likely to have female earners with good salaries and thus greater bargaining power? If so, does this parity among spouses actually create a more harmonious attitude toward giving, making it an enjoyable shared activity rather than a contentious case of spousal monitoring? These and other questions remain fascinating and important areas for understanding not simply charitable giving, but also for uncovering how households make decisions in general.

3.4 Experiments on Individual Givers: Price

An individual with consumption c, giving g, income y, and a marginal tax rate t, faces a budget constraint of ![]() , or

, or

![]() (1)

(1)

Letting ![]() then we see that the tax deduction lowers the price of giving, resulting in an out-of-pocket donation of

then we see that the tax deduction lowers the price of giving, resulting in an out-of-pocket donation of ![]() . A difficulty with estimating the effects of

. A difficulty with estimating the effects of ![]() and y on g is that t and y are determined jointly. One way to break the link between price and income is to look for an unanticipated change in the relationship, such as from a tax reform. Another way to get identification is through laboratory or field experiments that independently vary p or y.

and y on g is that t and y are determined jointly. One way to break the link between price and income is to look for an unanticipated change in the relationship, such as from a tax reform. Another way to get identification is through laboratory or field experiments that independently vary p or y.

A popular avenue for manipulating price both in actual fundraising and in experiments is from matching contributions. Suppose a rich philanthropist offers to match every dollar donated, d, with m dollars of his own. An out-of-pocket donation of d results in the charity receiving a gift of ![]() . Then when the charity receives g dollars, it only costs the giver

. Then when the charity receives g dollars, it only costs the giver ![]() , that is

, that is ![]() . For instance, under a 2-for-1 match it costs the donor $1 to give $3, so

. For instance, under a 2-for-1 match it costs the donor $1 to give $3, so ![]() . This results in a budget

. This results in a budget

![]() (2)

(2)

Notice that Eqs. (1) and (2) are quite similar. If ![]() then the two are the same.

then the two are the same.

A significant side issue is that, in practice, matching contributions typically have a limit. For instance, a philanthropist may pledge to match the first $100,000 donated. Then if donations exceed $100,000, the philanthropist’s “match” becomes equivalent to a direct contribution to the charity—no individual is being subsidized on the margin. If the limit is likely to be exceeded or, equivalently, the philanthropist cannot credibly commit to not giving the full limit pledged even if the match limit is not reached, then it is rational for givers to treat the match as simply a single unconditional grant. If this is the case, then the “matching grant” could in theory be expected to reduce individual donations d through an income effect. Since most matches do have limits that are exceeded,18 there is a question of whether donors suffer from a “matching illusion,” that is, whether they perceive that their contributions will actually result in more donations from the rich philanthropist, resulting in a substitution effect (encouraging giving) and an income effect (discouraging giving), or whether there is no matching illusion and a match results in only the income effect on d.

A second manipulation on price may be to offer a rebate. Suppose an individual gives g to the charity, and then shortly thereafter receives a rebate of r per dollar donated. The rebate could come from the government, a philanthropist, or the experimenter. This rebate now means that to give an additional dollar to the charity costs only ![]() to the donor, that is a gift g to the charity costs

to the donor, that is a gift g to the charity costs ![]() out-of-pocket. Thus the budget is

out-of-pocket. Thus the budget is

![]() (3)

(3)

Equations (1) and (3) are identical as long as ![]() . In fact, this point makes it clear that the tax deduction is in fact a rebate—only when one’s taxes are finally reconciled is the benefit of the deduction realized in a higher tax refund or lower tax bill. Looking at (1)–(3), modulo the “matching illusion” problem, if

. In fact, this point makes it clear that the tax deduction is in fact a rebate—only when one’s taxes are finally reconciled is the benefit of the deduction realized in a higher tax refund or lower tax bill. Looking at (1)–(3), modulo the “matching illusion” problem, if ![]() then the prediction from simple economic theory would be that the outcomes are the same.

then the prediction from simple economic theory would be that the outcomes are the same.

Experimental research on rebates and matches began with a provocative of experiment by Eckel and Grossman (2003). Endowing laboratory subjects with cash, they allowed subjects to give some of the money to a favored charity at set rebate rates r of 0, 0.2, 0.25, and 0.5. Another group of subjects faced the equivalent tasks but framed as a match, with m of 0, 0.25, 0.33, and 1. They found matching significantly dominated subsidies, with the charity receiving 27–88% more with matching. They also found an interesting pattern that we will return to later. Under the matching scheme, the out-of-pocket cost to the subject, that is ![]() , is a nearly identical fraction of the endowment on average for every value of

, is a nearly identical fraction of the endowment on average for every value of ![]() , ranging only between 47 and 52%. In other words, when one looks at the out-of-pocket donation

, ranging only between 47 and 52%. In other words, when one looks at the out-of-pocket donation ![]() , subjects allocated about the same d as fraction of their endowment to the charity, regardless of m. This could lead one to infer that the match does not matter. However, when looked at as the gift received,

, subjects allocated about the same d as fraction of their endowment to the charity, regardless of m. This could lead one to infer that the match does not matter. However, when looked at as the gift received, ![]() , it would lead one to infer that matches are hugely influential. In fact, if utility depends on the gift g, then the match has an income effect that should suppress d: a 1-to-1 match can reach the same g at half the d. But it also creates a substitution effect that should increase d. Thus, only if g is elastic with respect to p,

, it would lead one to infer that matches are hugely influential. In fact, if utility depends on the gift g, then the match has an income effect that should suppress d: a 1-to-1 match can reach the same g at half the d. But it also creates a substitution effect that should increase d. Thus, only if g is elastic with respect to p, ![]() , will d not fall in response to an increased match. Eckel and Grossman confirm this by estimating an elasticity of g with respect to p of about −1.1. If instead they had looked at the effects of m on d, the inference would have been that, after accounting for the endowment, m and d are virtually unrelated.19

, will d not fall in response to an increased match. Eckel and Grossman confirm this by estimating an elasticity of g with respect to p of about −1.1. If instead they had looked at the effects of m on d, the inference would have been that, after accounting for the endowment, m and d are virtually unrelated.19

A series of field experiments on matching grants finds results that in many ways parallel the laboratory studies. Karlan and List (2007) team with an actual nonprofit to send fundraising letters to over 50,000 potential donors, one third of whom acted as a control group. The letters to those treated varied in ways that are intended to capture the issues raised above. Letters included either no match, a 1-to-1, 2-to-1, or 3-to-1 match, that is, ![]() , or 0.25, respectively. They also addressed the “matching illusion” by claiming in the letter that matches would go up to $25,000, $50,000, or $100,000, thus increasing the likelihood that a giver would feel their contribution would truly be subsidized (assuming they see any unmatched portion of the limit as credibly not given).

, or 0.25, respectively. They also addressed the “matching illusion” by claiming in the letter that matches would go up to $25,000, $50,000, or $100,000, thus increasing the likelihood that a giver would feel their contribution would truly be subsidized (assuming they see any unmatched portion of the limit as credibly not given).

The mailing received a response rate of 2%, which is not atypical for charitable solicitations of this type. Of the 50,083 mailings, they received 300 control responses, and 735 treatment responses (roughly 245 per match level). While individual characteristics of the donors were not observable, the authors could control for census-level characteristics based on the zip codes of potential donors. Note also, there is no way to know that the envelopes were opened and, thus, who was treated. The authors would ideally wish to control who was treated and examine the effect of the treatment on the treated. Since this is impossible, the authors’ analysis uses either all 50,000 mailings as observations, or simply the 1035 who responded.20

The presence of any match had a significant impact on the likelihood of giving (0.018 for the control and 0.022 for the treatment), increasing the propensity by 22% (that is, 0.022/0.18–1). It also increased the donation d per solicitation by 19%, from $0.81 to $0.97. However, as the match increased from 1 to 2 to 3-to-1, out-of-pocket donations d per mailing remained flat at $0.94, $1.03, and $0.94, respectively, which is not a significant difference. However, if one looks at the total gift including the match, ![]() , one would conclude the match greatly increases generosity, going from $1.87 in the 1-to-1 match up to $3.75 per mailing in the 3:1 match.21

, one would conclude the match greatly increases generosity, going from $1.87 in the 1-to-1 match up to $3.75 per mailing in the 3:1 match.21

Interestingly, Karlan and List found no effect of the ceiling on the dollars to be matched. This would indicate that either donors did not suffer from a matching illusion, other than to perhaps change the timing of donations to fall under the period of the match, or that they all suffered similarly from marginal-illusion and the elasticity of g is roughly ![]() −1, which implies a constant d. Harkening back to the parallels with the laboratory study of Eckel and Grossman, who also found d independent of m, there is something yet to be understood about how individuals see a match as affecting the price.22 We return to this in the next section when we discuss leadership giving.

−1, which implies a constant d. Harkening back to the parallels with the laboratory study of Eckel and Grossman, who also found d independent of m, there is something yet to be understood about how individuals see a match as affecting the price.22 We return to this in the next section when we discuss leadership giving.

3.5 Experiments on Individual Givers: Leadership Gifts

A rule of thumb that fundraisers use when launching a fundraising campaign is that about one third of the announced goal should be committed prior to the announcement of the public campaign. That is, pledges made from a small group of donors to provide seed money—called “leadership gifts” by fundraisers—are seen as an essential part of fundraising.23

Andreoni (1998) presented a theory of seed money based on the charity having fixed costs (or equivalently, a range of increasing returns) associated with its operations. The consequence of the fixed costs is that even if there is an equilibrium that would allow the charity to reach its goal, there will also be an equilibrium in which no donations are received as long as the fixed costs exceed what any donor is willing to pay alone. The way the charity can eliminate the undesirable equilibrium is to get enough pledges to (almost) fully cover the fixed costs.24 Vesterlund (2003) and Andreoni (2006a) provide alternative explanations of seed money as conveying information. In both models there is a first mover (or movers) who are given or endogenously acquire superior information about the quality of the charity. Only by making large gifts can these informed players credibly convey that the charity is worth supporting at a high level.25

Bracha, Menietti, and Vesterlund (2011) provide a direct test of the fixed-costs model in a laboratory setting. The experiment has an elegant ![]() design. Groups play a public goods game where giving is either simultaneous (no lead giver) or sequential (a designated lead giver), interacted with the presence or absence of a fixed cost. In the presence of fixed costs that are binding on subjects (that is, they exceed the equilibrium with no fixed costs) the combination of high fixed costs and sequential play significantly increases the level of donations and the likelihood that the threshold is met. The experiment neatly supports the model’s predictions.

design. Groups play a public goods game where giving is either simultaneous (no lead giver) or sequential (a designated lead giver), interacted with the presence or absence of a fixed cost. In the presence of fixed costs that are binding on subjects (that is, they exceed the equilibrium with no fixed costs) the combination of high fixed costs and sequential play significantly increases the level of donations and the likelihood that the threshold is met. The experiment neatly supports the model’s predictions.

List and Lucking-Reiley (2002) provide a direct test of the effect of seed money in a field study. They contact donors to give to small public goods ($2000 computer work stations) with varying degrees of seed money provided. As in the laboratory, those solicitations that included the highest seed money gained the greatest likelihood of giving and the largest donations.

A recent field study by Huck and Rasul (2011) combines the reasoning about leadership givers with that of matching grants described above. They note that the very existence of a matching contribution is itself meaningful in the same way that a leadership gift can provide credibility that a fundraising goal will be met. Huck and Rasul test these ideas in a field experiment to raise money for disadvantaged families in Germany. The fund drive was sponsored by the Bavarian State Opera House, whose patrons served as the subjects in the field experiment.

The opera house mailed 14,000 solicitation letters to individuals who had purchased tickets to operas or ballets. This likely means the sample will be weighted toward more educated and higher income individuals. A control group did not receive any mention of a lead giver or a match. Treatment group 1 was simply told of a ![]() leadership gift. In two additional treatment groups the

leadership gift. In two additional treatment groups the ![]() leadership gift was mentioned, but it was framed as a limit on matching contributions. Treatment group 2 was told the match was 0.5-to-1, for an effective price of giving g of

leadership gift was mentioned, but it was framed as a limit on matching contributions. Treatment group 2 was told the match was 0.5-to-1, for an effective price of giving g of ![]() in, while in treatment group 3 the match 1-to-1, yielding a

in, while in treatment group 3 the match 1-to-1, yielding a ![]() . The inclusion of treatment group 1 distinguishes this study from Karlan and List and allows one to identify the effect of the match independent of the mere presence of a lead donor. That is, comparing the control to group 1 captures the effect of a lead donor, then comparing group 1 to groups 2 and 3 allows isolation of the effect of a match.

. The inclusion of treatment group 1 distinguishes this study from Karlan and List and allows one to identify the effect of the match independent of the mere presence of a lead donor. That is, comparing the control to group 1 captures the effect of a lead donor, then comparing group 1 to groups 2 and 3 allows isolation of the effect of a match.

Huck and Rasul found the biggest effect of the experiment was announcing the lead gift itself. Control group giving averaged ![]() , which increased to

, which increased to ![]() in group 1. That is, simply announcing the lead gift, without any match, raises giving by 78%. Adding the 0.5-to-1 match raised giving to

in group 1. That is, simply announcing the lead gift, without any match, raises giving by 78%. Adding the 0.5-to-1 match raised giving to ![]() , a 14% increase over group 1, and the 1-to-1 match raised giving to

, a 14% increase over group 1, and the 1-to-1 match raised giving to ![]() , a 40% increase over group 1. While these averages indicate that the gift g responds to reductions in price, the response is inelastic. This means that the match actually causes the out-of-pocket donation to fall in response to the match. Relative to group 1 there

, a 40% increase over group 1. While these averages indicate that the gift g responds to reductions in price, the response is inelastic. This means that the match actually causes the out-of-pocket donation to fall in response to the match. Relative to group 1 there ![]() , in group

, in group ![]() , and in group

, and in group ![]() .

.

Huck and Rasul have two important conclusions. First, using a control group that received a solicitation that has no mention of the lead gift, then one would find a very small effect of the match on out-of-pocket donations, as was found by Karlan and List. Second, and most importantly, they find that the largest effect of a match is in announcing the leadership gift, not in lowering the price. In fact, the charity in this experiment is best off by simply announcing a leadership donation and not including a match at all. This can explain why Karlan and List report that the existence of a match and not the size of the match is what matters. Huck and Rasul allow an even stronger statement: for the population of opera patrons in the study, giving g is mildly responsive to the match but is inelastic with respect to price. However, giving is highly responsive to the announcement of the lead gift, meaning that leadership gifts can encourage giving by others, but converting leadership giving into matching grants is counterproductive for the charity.

3.6 Experiments on Individual Givers: Give more Tomorrow

Thaler and Benartzi (2004) made famous a simple device that is successful at getting people to save in retirement funds. The program, called Save More Tomorrow (SMT), allows workers to commit in the present to save more at a date sufficiently far into the future. Compared to asking them to commit to save more immediately, the SMT program increases savings over the long run.

Breman (2011) uses the same logic to motivate an intervention she calls Give More Tomorrow (GMT). She works with a charity in Sweden that allows donors to sign up for automated monthly donations that are made electronically. In the control group, the charity calls donors with a request to increase their monthly donation starting at the next billing date, as is typical for charity operations. In two treatment groups, an identical script is used by the solicitor, except that they offer to begin the increased donation in 1 month or 2 months past the next billing date. She finds that a delay of 2 months, but not 1 month, had a significant positive effect on the increase in donations. Moreover, a year after the intervention, individuals who were treated with GMT continued to have higher donations and, compared to asking people to give more today, GMT increases the total receipts of the charity. This effect could be due to present-bias or planning constraints, or simply because it is harder to say “no” to requests for obligations far off into the future.26

3.7 The Salience of Incentives to Give

All of this analysis of the effect of tax incentives, matching grants, on individuals is, of course, built on the assumption that individuals understand the financial consequences of their donations on both themselves and the charities. A recent paper on the salience of “tax expenditures” by Goldin and Listokin (2012) uses a survey of US taxpayers to show that, while 72% of all tax filers correctly identify their eligibility to benefit from a charitable deduction, people systematically underestimate the value of the deduction. For instance, only 18% of those with a marginal tax rate of 0.28 correctly identified the subsidy on giving as “20–40%,” and 78% stated that the subsidy was below “20%.” As other findings of a lack of awareness of sales taxes and EITC benefits have led to a discussion of the impact and incidence of these policies (Chetty & Saez, 2013; Chetty, Looney, & Kroft, 2009), the lack of salience about the charitable deduction could generate similar conversations among academics and policy makers. Moreover, some of the differences discussed above could be explained through salience. For instance, do matching grants during fundraising campaigns make the consequences and costs of a gift more salient, and that is why they can be more effective? Are men more aware of marginal tax rates, and could this explain why households in which men decide on giving are more price sensitive? These and other effects of salience are, it would appear, promising and important areas of future research.

4 Approach 2: The Charitable Sector as a Market

The machine of charitable giving has many moving parts. Charities receive grants from the government, gifts from foundations, donations from individuals, and raise money through ordinary appeals like mailings, phone banks, and advertising, but also through fundraising events, like galas, walkathons, charity auctions, sponsorships, and in some cases by charging fees for services. The use, intensity, and effectiveness of each channel is likely affected by the use, intensity, and effectiveness of the other channels. This interdependence is clearly important and, obviously, presents a tremendous challenge for researchers. With charities as demanders of funds, donors as suppliers, and the government providing policy interventions that are dependent on choices made by donors and charities, identifying the “equilibrium” in this market becomes a delicate and difficult issue. This section looks at new theoretical and econometric studies that try to understand charitable giving from this more holistic approach.

4.1 Theories of Charity from the Supply Side

Early thinkers in the area of nonprofits, such as Weisbroad (1991) and Rose-Ackerman (1996), deserve credit for identifying and advocating a broad approach to charitable giving, and since then the research that takes both demand and supply aspects into account has grown tremendously. Most recently, an elegant theoretical model by Correa and Yildirim (2013) combines and generalizes models by Rose-Ackerman (1982), Andreoni (1998), Andreoni and McGuire (1993), and Andreoni and Payne (2003) to describe the equilibrium among donors and fundraisers, and to explore the impacts of government policies. In the model, fundraising is costly, individuals give only if they are solicited by the charity, each potential “target” donor has a different propensity to give based on heterogeneity across givers.27 Correa and Yildirim provide a solution in which the charity determines the set of potential donors for whom the “profits” are the highest, that is, for whom the marginal donation most greatly exceeds the margin cost of solicitation. Since the charity chooses the set of donors, and commits to a total fundraising cost C, it forces the donors into a subgame with fixed costs. In this subgame the set of donors who are solicited must contribute at least C or the charity will provide no net services. This non-convexity effectively creates a threshold, which in turn creates an equilibrium at giving zero (Andreoni, 1998). Correa and Yildirim show that if there also exists an equilibrium among some set of donors where this equilibrium at zero can be overcome, then a clever charity can select the set of donors that guarantee it will be overcome and the charity will have a successful fundraising campaign.

The Correa-Yildirim model also has interesting and important policy predictions. Foremost among these is the prediction about crowding out of private donations by government grants to charities. The classic model of charity coming from purely altruistic motives indicates that individuals should be indifferent to giving directly or through their taxes, thus grants should crowd out donations dollar-for-dollar. Since crowding out is often measured as incomplete, one reason could be that preferences are not purely altruistic but include a warm-glow, as discussed in the prior section. This is a supply side explanation. The Correa-Yildirim model, maintaining altruistic preferences, provides a demand side explanation instead (while the proofs are provided under an assumption of pure altruism, the results are made only stronger by including a warm-glow). Because of the strategically active charity, and the endogeneity of the set of donors through fundraising, the model prediction is that grants will only be partially crowded out, and that some of this crowding out will be attributable to reductions in fundraising efforts by the charity in addition to classic direct crowding out of donors. As we see below, this is fully in line with the results from recent econometric analyses of charitable organizations.

4.2 Econometric Evidence

The most natural policy question applying the market approach to charities is crowding out. Testing theories of crowding out, however, has been a challenge. For instance, how does one pair private giving to public funding for the same type of good, and should the analysis constrain coefficients that measure crowding out to be the same across different types of charitable goods? What about donors who may give to multiple goods—can government grants to one charity affect giving to another? And could the government actually crowd in giving by providing a signal of quality, and should this vary depending on how easily quality can be publicly verified?

What is the best methodology for pairing private and public funding?28 Kingma (1989) was the first to match private giving and public funding directly by focusing on giving to local public radio stations.29 Schiff and Weisbrod (1991) gathered measures of private giving from non-profit tax returns but then matched these measures to aggregated measures of government funding. Hungerman (2005) and Gruber and Hungerman (2007) match church spending on charitable goods with aggregate measures of government spending. Khanna, Posnett, and Sandler (1995) and Payne (1998) were among the first to match both private and public giving to specific charities and for a large sample of charities. Another approach, taken by Andreoni and Payne (2011a), is to look at crowding out by different categories of donations, that is, tax receipted versus non-tax receipted giving by individuals, and transfers from foundations and from other charities.

An underlying econometric issue when seeking to measure the relationship between private and public funding is how best to control for dynamic changes in giving. Primary estimation issues revolve around concerns of heterogeneity in the charities due to size, scope, mission, and location. One means to help control for this heterogeneity is in the use of panel data (e.g., Khanna, Posnett & Sandler, 1995; Payne 1998, 2001; Gruber & Hungerman, 2007; Hungerman, 2005; Okten & Weisbrod, 2000; Ribar & Wilhelm, 2002; Andreoni & Payne 2003, 2011a, 2011b). With panel data, one can include organizational fixed effects to help control for time-invariant differences across charities.

A second key concern in estimation is the potential omitted variable bias due to time-varying events that could drive both the government and private donors to simultaneously change giving. For example, a natural disaster (Haiti earthquake, Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy) is likely to increase both private and public funding. Failing to control for these positive correlations in demands will lead to a biased understatement of the degree of crowding out, and could erroneously even suggest crowding in.

There is likely a similar downward bias associated with the endogeneity in public funding, the third main concern. As pointed out by Payne (1998), donors are also voters. If voters’ preferences are reflected in both public policy and in private donations, it will create a biased impression that crowding out is low. Hence, even with panel data estimation, one must be concerned about the exogeneity of government funding in a specification that has private giving as a dependent variable.

Estimations of crowding out, thus, should control for the heterogeneity among charities and take into account potential omitted variable and endogeneity biases. This suggests that unless one has conducted a field experiment or has a strong natural experiment, an OLS type of regression will underestimate (bias toward a more positive coefficient) the effect of government funding on private donations. Most of the current research has relied on two-stage least squares (“2SLS”) framework to address issues of endogeneity and omitted variable bias. This requires that one find measures that directly explain variations in government funding but only indirectly (through the government funding channel) explain private giving. Although 2SLS is a popular and useful technique, it has its limitations. The biggest concern is weak instruments (see, Bound, et al., 1995; Choa & Swanson, 2005; Cruz & Moreira, 2005). If one uses instruments that only weakly identify the level of government funding, the estimates of crowd out will still be biased. In any 2SLS estimation, therefore, the researcher should ensure that the instruments work, that there is a good story to explain how the instruments affect government funding, and that the instruments do not directly explain private giving.

The literature that employs a 2SLS technique, generally finds that government funding crowds out private giving. Hungerman (2005) suggests that public social welfare funding crowds out revenues by faith-based organizations on the order of 67 cents for every dollar of public funding. Andreoni and Payne (2011a) find an overall crowd out of 70 cents for every dollar of government grants when studying charities involved in the provision of goods related to social welfare and community development. These use data from the United States. Andreoni and Payne (2011b) use data on Canadian charities and measure crowding out at close to dollar-for-dollar.

Is the measure of crowding out usually the same across different types of charities? While crowding out seems large for social welfare organizations, there is no evidence of crowd out for health organizations or for overseas and relief organizations.30 Borgonovi (2006) studies the effects of changes in government funding on private giving to American non-profit theaters. He presents evidence to suggest that small levels of government funding crowd in private donations but large levels of funding crowd out donations. However, Borgnovi only studies a small sample of charities. In the context of education, the analysis of both Connolly (1997) and Payne (2001) suggests that donors may not be as informed about the goods and services provided by universities, potentially allowing the government grants to serve as a signal of quality to private donors, especially when the signal relates to grants associated with research activity. Both empirical analyses support this conjecture. Recent work by Blume-Kohout (2012) also suggests that government research grants provide a signal of quality to private donors.

Overall, however, while there are numerous studies that explore crowd out as it relates to the provision of social services, there are too few studies that examine crowding out in other charity sectors, such as environmental, health, education, and the arts.

If crowding out ranges from 70 cents to 1 dollar, is this mostly attributable to a change in donor behavior? There are several things to consider in answering this. First, donors may be latent givers, that is, they must be encouraged to give through fundraising and marketing campaigns. Second, charities are likely more concerned about service provision than revenue growth. That is, as non-profits, charities may not be net revenue maximizers and instead may view fundraising as a “necessary evil.” Third, it is important to control heterogeneity among charities when analyzing the interaction between private and public funding. In short, it is important, yet delicate, to treat charities as active players when it comes to the collection of private donations.

Andreoni and Payne (2003, 2011a) shed light in the role of charity fundraising on crowding out using US data. In 2003 they demonstrate that for both arts and social welfare charities, increases in government funding to an organization significantly decrease fundraising efforts by the organization. In 2011 they study a panel of more than 8000 charities operating in the United States. They measure an overall level of crowding out on the order of 75%. This crowding out can be decomposed into the portion that is attributable to donors independently changing their contributions and the portion attributable to a change in fundraising behavior. Their research suggests the bulk of the crowding out is due to a change in charity fundraising. Depending on the specification, in fact, donors may be slightly crowded in by government grants. The maximum level of crowd out attributable to a direct change in donors’ giving is 30%. Thus, the portion of crowding out attributable to a change in the charity’s behavior ranges between 70% and 100%.

Andreoni and Payne (2011b) expand upon these findings with a rich data set of more than 13,000 charities involved in the provision of social welfare and community services in Canada over more than 15 years. For overall private giving, they measure crowding out of close to 100%. Similar to the US data, approximately 77% of this crowding out is attributable to change in charity fundraising. Unlike the US data, however, Andreoni and Payne can examine whether crowding out is similar across different types of private givers to the charity: individuals that give directly, individuals that give through participation in fundraising events (such as gala dinners or other non-tax receipted revenues), and donations from other charities and charitable foundations. The analysis suggests that individuals that give directly do not reduce their giving when the charity receives a government grant – instead they increase their giving, suggesting a crowding in effect as would occur if individuals use government funding as a signal. The crowding out is attributable to a decline in revenues from fundraising events (likely because the charities reduce their fundraising efforts) and a decline in revenues from other charities and foundations. These other charities and foundations are likely better informed about the activities of the charities under study and, thus, more likely to change their funding levels when the charity receives government funding.

Despite the great attention to crowding out, there remain many open questions. Crowding out clearly differs across the types charitable good or service being provided, and it differs across each source of private revenue, in ways that are not yet understood. Moreover, if giving is crowded out, where does the giving go? Do donors give it to another cause or use it for private consumption. Conversely, if a fundraiser succeeds in attracting a new donor, is that money simply moved from another charity, or is the new donor also giving new dollars to the charitable sector.31 One thing that is clear, however, is that viewing organizations as active players in the market for donations has brought rich new insights to questions of crowding out and the effectiveness of government policy.

4.3 Evidence from Field Experiments

The main models of fundraising discussed above are built on the assumption that there are some latent transaction costs to giving. Contacting donors with a request to give, perhaps providing a return envelope and information about the organization, can lower the transaction costs and hence trigger a gift. We start this section by discussing a paper by Huck and Rasul (2010) that attempts to measure the selection into giving based on a model of transaction costs.

Notice that if an individual faces random transaction costs—one’s day could be particularly busy or unusually slow—this effect cannot be captured in a single request to give. Thus, one needs at least two requests to identify a model of selection into the set of donors. Huck and Rasul conduct a study using the same fund drive described above. Potential donors received a detailed solicitation letter that varied across donors with respect to whether a leadership gift was mentioned and potential matching rates for donations. Six weeks later these donors received a brief reminder of the earlier mailing but carried no new information. Let ![]() be the response rate on the first mailing and

be the response rate on the first mailing and ![]() be the response rate on the second mailing. Let s stand for the share of donors who would like to give if transaction costs were sufficiently low and let t be the probability that an individual draws a transaction cost that is at or below the threshold at which they will find the time to consider the solicitation and mail a check. Assuming s and t are the same across solicitations (the authors provide cogent arguments about why the data support this assumption), then with two mailings the response rates would be defined as