Taxation and Development

Timothy Besley* and Torsten Persson†, *LSE and CIFAR, †IIES, Stockholm University and CIFAR

Abstract

The central question in taxation and development is: “how does a government go from raising around 10% of GDP in taxes to raising around 40%?” This paper looks at the economic and political forces that shape the way that fiscal capacity is created and sustained. As well as reviewing the literature and evidence, it builds an overarching framework to help structure thinking on the topic.

Keywords

Fiscal capacity; Taxation; Development; Administration and compliance; Revenue authorities

It is shortage of resources, and not inadequate incentives, which limits the pace of economic development. Indeed the importance of public revenue from the point of view of accelerated economic development could hardly be exaggerated.

Nicholas Kaldor, “Taxation for Economic Development,” Journal of Modern African Studies, 1963, p. 7.

1 Introduction

Perhaps more than any other economist in the post-war generation, Nicholas Kaldor appreciated the centrality of public finance to development. Following his lead, we believe that the power to tax lies at the heart of state development. A moment’s reflection on the history of today’s developed countries and the current situation of today’s developing nations suggests that the acquisition of that power cannot be taken for granted. The central question in taxation and development is: “how does a government go from raising around 10% of GDP in taxes to raising around 40%?”

In the process of development, states not only increase the levels of taxation, but also undergo pronounced changes in patterns of taxation, with increasing emphasis on broader tax bases, i.e., with fewer exemptions. Some taxes—notably trade taxes—tend to diminish in importance. Thus, in the developed world taxes on income and value added do the heavy lifting in raising sufficient revenue to support the productive and redistributive functions of the state.

The power to tax is taken for granted in most of mainstream public finance. Traditional research focuses on limits imposed by incentive constraints tied to asymmetric information, or sometimes political motives, rather than the administrative capabilities of the state. Thus, public finance and taxation remains a relatively unexplored field. However, this is now changing with a better understanding of the issues at a macro level and a range of efforts to collect micro data, some of it based on policy experiments. In part, this reflects a growing insight among policymakers that a better working tax system helps the state to support economic development.

Governments in all parts of the world and at all points in history have faced similar challenges when it comes to funding their ambitions. We do not believe that governments in the past or in today’s developing world are any less rational or farsighted compared to those in today’s developed world. But they may face incentives and constraints shaped by weakly institutionalized political environments. A key challenge for the study of taxation and development is to understand how these incentives and constraints work, and how—if at all—the situation might be improved for the citizens in today’s developing nations.

Against this background, we take the view that governments in poor countries do their best in raising taxes, given the administrative structures in place and the political incentives they face. The real question then becomes why the supporting administrative structures remain so weak in many places. To answer it requires an analysis of endogenous fiscal capacity which is sometimes in the literature referred to simply as state capacity. Crudely, this concept captures how much tax a government could potentially raise given the structure of the tax system and its available powers of enforcement. But as a government need not always operate at or near the level of fiscal capacity, its capacity may not be directly observable.

We view the creation of fiscal capacity as a product of investments in state structures—including monitoring, administration and compliance through e.g., well-trained tax inspectors and an efficient revenue service. Our approach gets away from the false juxtaposition between positive and normative analyses of optimal taxes on the one hand, and studies of tax administration and political economy on the other.1

Economists who have studied taxation and development have tended to see the evolving economy as the driving force behind the government’s approach to taxation. However, we will argue that this standard economic view needs to be augmented by an understanding of how political incentives shape the evolution of the tax system. This argument is in line with Schumpeter (1918), who saw the development of the tax system as intrinsically intertwined with the nature of the state and its history. Moreover, we will draw on the modern approach to development, which puts political motives (and the role of institutions) at the heart of understanding economic change.2 Without invoking political motives as shaped by institutions, it is difficult to explain why some countries are rich and others are poor in the first place.3

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows. In Section 2, we briefly discuss different perspectives on taxation and development, and outline our own perspective in more detail. Section 3 presents some background facts on levels and patterns of taxes in rich and poor countries and countries with strong and weak political institutions. Section 4 presents our analytical framework to study the equilibrium choices of taxation and investments in fiscal capacity. In Section 5, we use this framework to identify different determinants of taxation and fiscal capacity: economic development, political institutions, social structures, the value of public spending, non-tax revenues like aid and resource rents, and tax administration. Section 6 concludes.

2 Perspectives on Taxation and Development

There can be little doubt that the nature of the economy, and its structural characteristics, influence the ability to tax and the types of taxes that can be imposed. The standard economic approach to taxation and development focuses on how economic change influences the evolution of the tax system. In this approach, changes to the tax system reflect structural change. For example, a declining informal sector widens the tax net, the growth of larger firms creates a vehicle for compliance, and expansion of the financial sector encourages transparent accounting procedures which facilitate taxation. Such structural approaches have been emphasized in the influential commentaries of Tanzi (1987, 1992) and the review of the issues by Burgess and Stern (1993). Important recent contributions, focusing on specific economic channels, include Gordon and Li (2009), who emphasize the link between taxation and formal finance, and Kleven, Kreiner, and Saez (2009) who emphasize third-party reporting through firms.

Of course, the standard economic approach also studies the influence of the tax system on the economy. Well-designed tax systems can minimize the efficiency losses imposed by taxes and even raise the growth rate in endogenous-growth models, as in Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1992). Tax revenues can be spent on public goods and investments that make the economy more productive, as in Barro (1990). Tax design in a developing country context has to take into account the information about behavioral responses needed by governments, as in the papers collected in Gordon (2010) and Newbery and Stern (1987).

The standard economic view has also dealt with the issues of administration and compliance—see Slemrod and Yitzhaki (2002) for an overview. These issues also take center stage in the influential writings of Richard Bird (see, e.g., Bird & Oldman, 1980).4 Looking at the recent experience through the lens of effective administration, Bird (2004) observes that “the best tax policy in the world is worth little if it cannot be implemented effectively”. The greater reliance on trade taxes (and seigniorage) than income taxes in poor economies, which we discuss further below, has been noted and discussed by many authors—see Burgess and Stern (1993), Hinrichs (1966), and Tanzi (1992), for early contributions.

But important as it is, economic development does not mechanically translate into increases in the tax take. Even in fast-growing economies, such as India and China, decisions by the state are needed to yield a dividend in the form of a higher tax share in GDP. For example, Piketty and Qian (2009) argue that increases in exemptions have meant that income tax revenues in India have stagnated at around 0.5% of GDP since 1986. Widening the scope of taxation to broad bases as income and value added is only feasible if accompanied by investments in compliance structures.

In summary, the standard economic approach views low levels of revenue and disproportionate reliance on narrow tax bases as important constraints on the tax take. This standard economic view is summarized schematically in Figure 1.

Whether or not administration, and compliance is given a central role, most of the work in the standard economic approach has little room for endogenous government behavior. By contrast, historical accounts of how tax systems have evolved, such as Brewer (1989) and Dincecco (2011), put a great deal of emphasis on government behavior and motives for raising taxes.5 These accounts suggest that it is essential for the study of taxation and development to focus on conscious efforts to build fiscal capacity.

A first feature of our approach in this chapter is to augment the standard approach by giving not only economic factors but political factors as well key roles in the analysis of taxation and development.6 This is in tune with the thrust of modern research on development, which sees political motives as central to understanding how development proceeds and to explain why some countries languish while others prosper. In keeping with this approach, we highlight the structure of political institutions and the degree of political instability as key drivers of investments in fiscal capacity. Changes in the power to tax may also reflect circumstances—e.g., threats of foreign conflicts—that forge common political interests in building a strong state.

A second feature of our approach is to point to a further endogenous feedback loop from taxation to development which has not featured in most discussions to date. When the government has a larger stake in the economy through a developed tax system, it has stronger motives to play a productive role in the economy, as a complement to its extractive role. Obvious examples include building high-return infrastructure projects and developing the legal system to reduce the extent of informality in the economy. Such complementarity can create a virtuous circle between taxation and development that goes beyond the standard technocratic view of government.

Both of these features are incorporated in the analysis of this chapter, as illustrated schematically in Figure 2.

The approach that we adopt sees tax compliance as something more than a technical issue. Observed compliance also reflects the underlying incentives of policymakers to improve the tax system and ensure that taxes are paid. This contrasts with the purely economic approach in thinking about better compliance structures and broader tax bases as a result of purposive, forward-looking activity by politically motivated incumbents. In this sense, our approach is related to earlier theoretical and empirical work by Cukierman, Edwards, and Tabellini (1992) on how the use of seigniorage depends on the efficiency of the tax system, and how the strategic choice of the latter depends on factors like political stability and polarization.

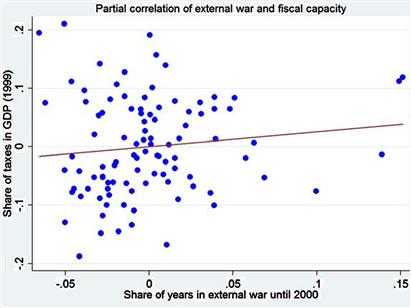

A focus on political economics also rhymes well with the extensive work by political and economic historians on how a state’s fiscal capacity evolves. Scholars of history have emphasized the key role of government motives to build fiscal capacity, and especially the centrality of warfare in stimulating demands for fiscal capacity. This research has yielded many interesting case studies, such as Bonney (1999), Brewer (1989), and O’Brien (2001, 2005). But there are also attempts at broader generalizations, as in the work by Hoffman and Rosenthal (1997), Levi (1988), Schumpeter (1918), and Tilly (1985). Tilly, in particular, aims at explaining European exceptionalism, although his work appears greatly inspired by the encyclopedic scholarship of German historian Hintze (1906). Much debate still remains about whether the fiscal state necessarily follows a pattern of war, with Centeno (1997) arguing that Latin America may be an exception to the Tilly hypothesis of war as a major motive for building fiscal capacity.

The fact that many states remain unable to levy broad-based taxes is often seen as key to the persistence of weak states in many poor countries, by development scholars like Migdal (1988). Others, such as Herbst (2000), have ventured the hypothesis that some countries in Africa might have been able to strengthen their weak states if external wars had been more frequent on the continent. By picking up similar themes, our approach thus parallels the approach taken by scholars in other branches of social sciences as well as the humanities.

Political scientists and sociologists sometimes push the role of taxation in development even further, by arguing that taxation can be a catalyst for political and economic change. This view is illustrated in Figure 3, where political institutions respond to an expanding tax domain. The old American adage of “no taxation without representation” is a vivid instance of such thinking, whereby demands for transparency and representation are built as part of the need to build a strong fiscal state in a “fiscal contract” between the citizens and the state.

In the remainder of the chapter, we first present some useful background facts on taxation and development. We then develop our approach, beginning with an exclusive focus on economic factors, as in Figure 1. Next, we consider how political incentives affect the arguments and give a well-defined role for political institutions in determining how tax systems develop, as in Figure 2. Endogenous political institutions as in Figure 3, however, lie beyond the scope of this chapter, although we briefly return to this possibility in the concluding remarks.

3 Background Facts

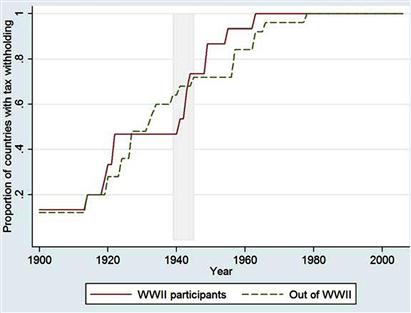

The growth of the state and its capacity to extract significant revenues from citizens is a striking economic feature of the last two centuries. For example, Madisson (2001) documents that, on average, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK raised around 12% of GDP in tax revenue around 1910 and around 46% by the turn of the Millennium. The corresponding US figures are 8% and 30%. Underpinning these hikes in revenue are a number of tax innovations, including the extension of the income tax to a wide population. For example, large-scale compliance with the income tax required states to build a tax administration and implement withholding at source. Such investments in fiscal capacity have enabled the kind of mass taxation now considered normal throughout the developed world.7

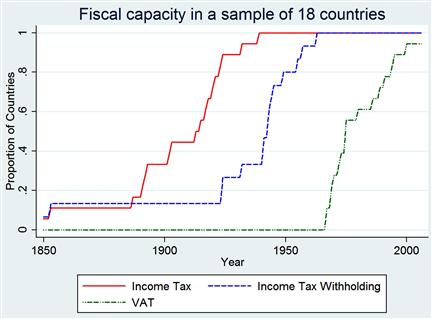

Figure 4 gives a partial picture of how fiscal capacity has evolved over time based on a sample of 18 countries using data from Mitchell (2007a,b,c). We will use this sample for time-series comparisons throughout this section.8 The figure plots the distribution of three kinds of changes in tax systems since 1850 which can be thought of as fiscal-capacity investments. The solid line shows the proportion of countries that have introduced an income tax, the dashed line shows the proportion that have implemented income-tax withholding, and the line with a mixture of dots and dashes shows the proportion that have adopted a VAT. Although a useful illustration for a limited sample of countries, the reader should bear in mind that looking at dates for these significant discrete changes almost certainly understates the extent of change since, over time, the reach of the income tax, withholding, and VAT have all increased. The graph shows that income taxes began appearing in the mid-nineteenth century, direct withholding follows somewhat later with both being found in the full sample by around 1950.9 VAT adoption lagged behind the income tax and with only the USA not having adopted a VAT in our sample of 18 countries by the end of the year 2000.

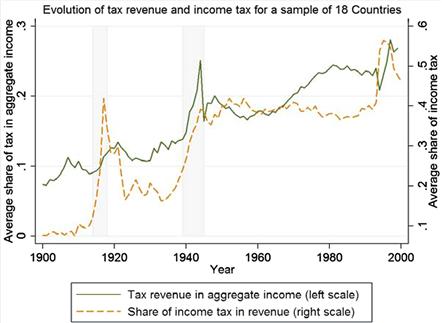

The model developed in Section 3 below will be used to explain the forces that shape such changes in the tax system. The changes illustrated in Figure 4 are all associated with investments in administrative structures that support tax collection.10 Figure 5 looks in more detail at the historical picture over time during the last 100 years for the 18 countries in our sample. The figure illustrates how the average tax take has increased over time from around 10% in national income to around 25% in the sample as a whole. Equally striking is the increasing reliance on income taxation which only made up about 5% of revenues in 1900 but about 50% by the end of the last century. These hikes in the income tax share during the two world wars, and the ratchet effect associated with them, also stand out in Figure 5.

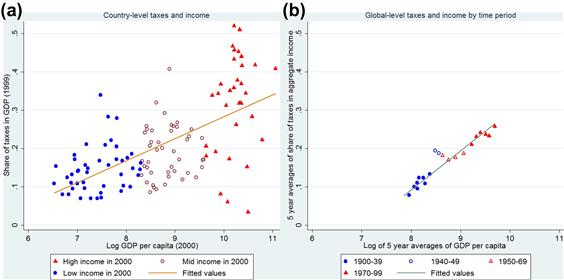

However, the narrow sample in Figures 4 and 5 ignores many of the poorer countries in the world. We would also like to use the model in this chapter to understand how fiscal capacity varies over countries. A first salient feature of the data is that richer countries tend to raise more tax revenue as a share of national income than poorer countries. This is illustrated in Figure 6. The left panel plots the overall tax take as a share of GDP from Baunsgaard and Keen (2005) against the log of GDP per capita from the Penn World Tables, both measured around the year 2000, and distinguishes observations by income. The right panel looks at the same relationship instead using the time-series data on our sample of 18 countries from Mitchell (2007a,b,c) to plot 5-year averages of the tax share over the 20th century against national income from Maddison’s data, and distinguishing observations by time period. The cross-section and time-series patterns are strikingly similar. Higher-income countries today raise much higher taxes than poorer countries, indicating that they have made larger investments in fiscal capacity. Moreover, the tax share in GDP of today’s developing countries does not look very different from the tax take 100 years ago in the now developed countries.

To probe further into tax differences across countries, it is interesting to look at the relative uses of different types of taxes, differentiated by the investments that they require to be collected. Arguably, trade taxes and income taxes are the two polar cases. To collect trade taxes just requires being able to observe trade flows at major shipping ports. Although trade taxes may encourage smuggling, this is a much easier proposition than collecting income taxes, which requires major investments in enforcement and compliance structures throughout the entire economy. We can thus obtain an interesting indication of fiscal-capacity investments by holding constant total tax revenue, and ask how large a share of it is collected from trade taxes and income taxes, respectively.

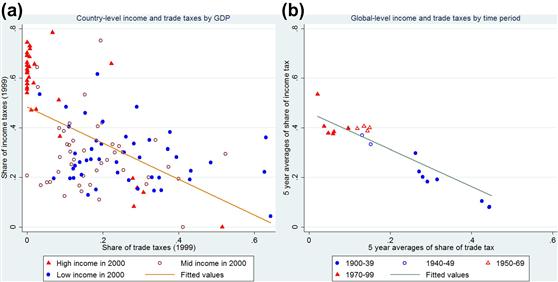

These shares are plotted against each other in Figure 7.11 Again, we report the cross-sectional pattern for the year 2000, based on contemporaneous data from Baunsgaard and Keen (2005), as well as the time-series pattern over the last 100 years based on historical data from Mitchell (2007a,b,c). The income-tax share is displayed on the vertical axis, and the trade-tax share on the horizontal axis. We observe a clear negative correlation: countries that rely more on income rely less on trade taxes. The left panel also shows a striking pattern by income: high-income countries depend more on income taxes, while middle-income and, especially, low-income countries depend more on trade taxes. The right panel of Figure 7 shows that the move from trade to income taxes is also reflected in the historical development of tax systems, as all countries have become richer. Again, the cross-sectional and time-series patterns look conspicuously alike with a similar slope of the regression lines.

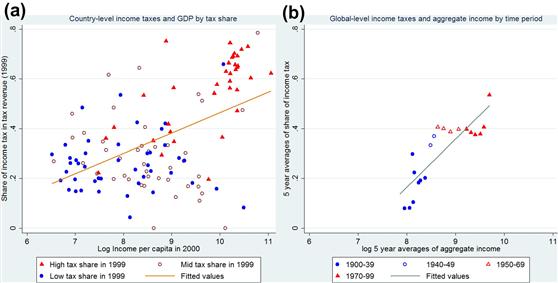

Figure 8 homes in on the income tax, plotting the relationship between the share of income taxes in total taxes and income per capita, in the current cross-section as well as the historical time series. The left panel separates the observations into three groups by tax take: countries that raise more than 25% of taxes in GDP, countries that raise 15–25% of taxes in GDP, and countries that raise less than 15%. The countries in the high-tax group again look markedly different, raising much more of their tax revenues in the form of income taxes. The right panel again differentiates observations by time period. The historical trend in this sample of older nations and the pattern in the world today is again very similar.

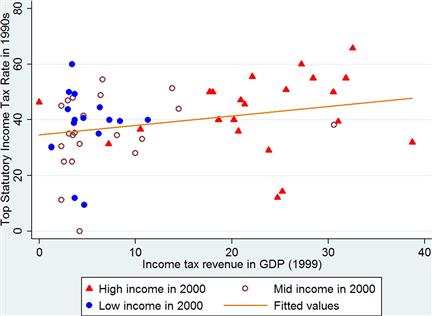

Another indicator of fiscal capacity is the relation between statutory tax rates and actual tax take. Figure 9 plots the top statutory income-tax rates in 1990s for the 67-country sample in Gordon and Lee (2005) against the share of income taxes in GDP from Baunsgaard and Keen (2005). The figure shows that the distribution of the top statutory rate is about the same among high-income and low-income countries. Obviously, the figure does not take aspects such as coverage and progressivity into account. With this qualification, the fact that high-income countries raise much more income-tax revenue than low-income countries suggests that a narrow tax base driven by compliance difficulties is a much bigger issue among low-income countries. This reinforces the earlier observation that fiscal capacity is considerably less developed in poor countries.

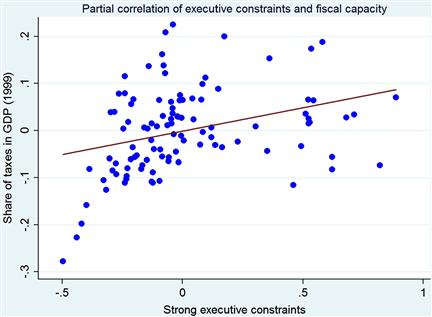

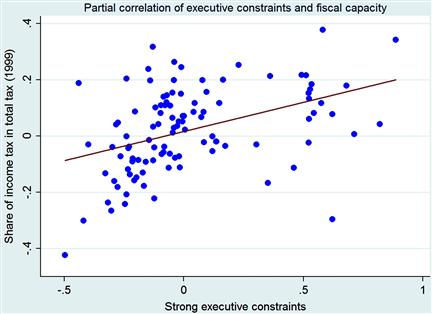

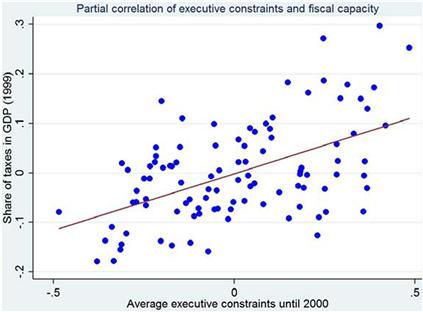

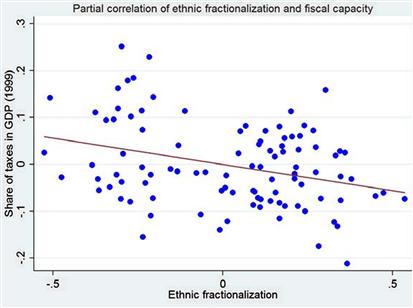

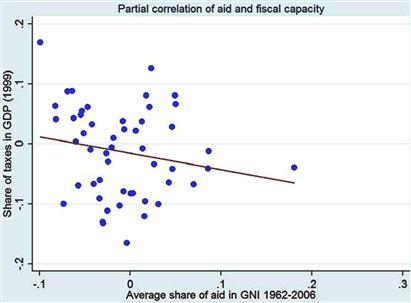

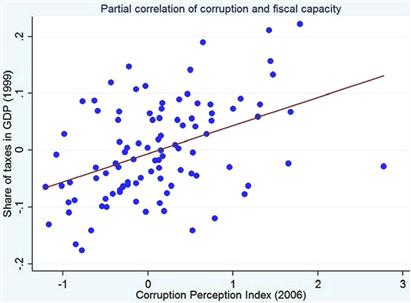

Finally, we turn to some facts relating tax structure and politics. As our core measure of political institutions, we use an indicator of executive constraints from the well-known Polity IV database (see Marshal and Jaggers, 2010). We use the highest coding of such constraints (the variable x-const is equal to 7 on a 1–7 scale) to measure the proportion of years since independence (or since 1800 if independence is earlier) that a country had strong constraints on the executive. To highlight that this political dimension captures something different than country heterogeneity in income, we control for current income before plotting the partial correlation of high executive constraints and two of our fiscal-capacity measures: total tax share in GDP (Figure 10) and the income tax share in total income (Figure 11). In both cases, we see a clear positive correlation between this measure of political institutions and fiscal capacity, taking the level of economic development into consideration—in Figure 10 the correlation hinges mainly on the countries with very low executive constraints (relative to income). The facts illustrated in these figures illustrate the need to adopt an approach where political factors help shape the level and evolution of fiscal capacity.

Taken together, the cross-sectional and time-series data suggest the following seven facts:

Fact 1: Rich countries have made successive investments in their fiscal capacities over time.

Fact 2: Rich countries collect a much larger share of their income in taxes than do poor countries.

Fact 3: Rich countries rely to a much larger extent on income taxes as opposed to trade taxes than do poor countries.

Fact 4: High-tax countries rely to a much larger extent on income taxes as opposed to trade taxes than do low-tax countries.

Fact 5: Rich countries collect much higher tax revenue than poor countries despite comparable statutory rates.

Fact 6: Countries with strong executive constraints collect higher tax revenues, when income per capita is held constant, than do countries with weak executive constraints.

Fact 7: Countries with strong executive constraints rely on a higher share of income taxes in total taxes, when income per capita is held constant, than do countries with weak executive constraints.

Together, these seven facts suggest strongly that rich, high-tax, and executive-constrained states have made considerably larger investments in fiscal capacity than have poorer, low-tax, and non-executive-constrained states.

Given these clear patterns in the data, it is indeed surprising that economists have not devoted much attention to dynamic models of economic and political determinants of fiscal capacity. As discussed in Section 2, most normative and positive theories of taxation hardly ever touch upon lacking administrative infrastructure as an important constraint on the taxes that governments can raise.

4 Framework

The framework that we develop in this section is a generalization of the models studied by Besley and Persson (2009a,b, 2011a,b,c). Our specific approach in this chapter also builds on the recent literature on how taxable income responds to taxes, allowing for a wider range of responses than the traditional view based on labor-supply elasticities—see Feldstein (1995, 1999) for the original contributions and Slemrod (2001) for a formulation close to the one we adopt.12 This makes particular sense in a developing country context, where non-compliance and decisions to earn or spend in the informal (untaxed) sector are such important issues. We build a framework to help us understand the forces behind the decisions to build a more effective tax system, where such decisions are made by a forward-looking government. In keeping with the stylized facts, we model larger fiscal capacity as increasing the yield on statutory taxes by reducing the extent of non-compliance.

The core focus is on the taxation of labor income and of goods and services which fall directly on households. This neglects the important issue of taxation of firms. Nor does the framework deal explicitly with taxation of capital income. We also limit attention to a centralized tax system, ignoring the complications created by local taxation and federal structures.

Basic Set-Up: Consider a population with ![]() distinct groups, denoted by

distinct groups, denoted by ![]() , where group

, where group ![]() is homogeneous and comprises a fraction

is homogeneous and comprises a fraction ![]() of the population. In principle, these groups could be regions, income/age groups, or ethnicities. There are two time periods:

of the population. In principle, these groups could be regions, income/age groups, or ethnicities. There are two time periods: ![]() . The economy has

. The economy has ![]() consumption goods, indexed by

consumption goods, indexed by ![]() . Consumption of these goods by group

. Consumption of these goods by group ![]() in period

in period ![]() is denoted by

is denoted by ![]() . There is also a traditional (non-rival and non-excludable) public good

. There is also a traditional (non-rival and non-excludable) public good ![]() . Individuals in group

. Individuals in group ![]() supply labor,

supply labor, ![]() , and choose how to allocate their income across consumption goods. This is a small open economy with given pre-tax prices of

, and choose how to allocate their income across consumption goods. This is a small open economy with given pre-tax prices of ![]() . Wage rates

. Wage rates ![]() are potentially group-specific and may vary over time.

are potentially group-specific and may vary over time.

Taxation and tax compliance: The government may levy taxes on labor income and all goods except the untaxed numeraire, good ![]() . The post-tax price of each good is:

. The post-tax price of each good is:

![]()

while the net wage is:

![]()

where ![]() is the vector of tax rates.

is the vector of tax rates.

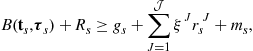

As in the standard model, statutory tax policy is a vector of tax rates for commodities and labor supply. However, to allow for non-compliance, we suppose that tax payments can be reduced by actions by those who are obliged to remit taxes to authorities. If the costs of non-compliance were large enough, then this would not happen and we would be back in the standard model. But we suppose this may not be the case and allow the cost of non-compliance to depend on investments in fiscal capacity.

To capture these ideas simply, we assume that tax payments to the government from group ![]() in period

in period ![]() , associated with the commodity tax imposed on good

, associated with the commodity tax imposed on good ![]() , are:

, are:

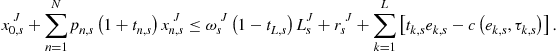

![]()

which we assume to be non-negative. Thus, ![]() (denominated in the units of the numeraire good) is the amount of the statutory tax which is not paid—think about

(denominated in the units of the numeraire good) is the amount of the statutory tax which is not paid—think about ![]() as purchases from the informal sector. The cost function for such non-compliance is the same for all groups

as purchases from the informal sector. The cost function for such non-compliance is the same for all groups ![]() , namely

, namely ![]() with

with ![]() increasing and convex in

increasing and convex in ![]() .The parallel expression for labor taxes is

.The parallel expression for labor taxes is

![]()

with cost ![]() . Analogously, one can interpret

. Analogously, one can interpret ![]() as the amount of work undertaken in the informal sector.

as the amount of work undertaken in the informal sector.

The vector ![]() represents investments in fiscal capacity which affect non-compliance costs. For each tax base,

represents investments in fiscal capacity which affect non-compliance costs. For each tax base, ![]() , we assume:

, we assume:

![]()

such that greater fiscal capacity makes avoiding taxes more difficult.13 Moreover, we postulate that ![]() , i.e., for a tax base where the government has made no investments in fiscal capacity, the cost of evading taxes is negligible. If citizens evade taxes fully when it is costless to do so, no tax revenue is raised from that base.

, i.e., for a tax base where the government has made no investments in fiscal capacity, the cost of evading taxes is negligible. If citizens evade taxes fully when it is costless to do so, no tax revenue is raised from that base.

For simplicity, we have assumed that fiscal capacity has a common effect on all individuals’ abilities to avoid paying statutory taxes. As a consequence, every consumer in the model adjusts their non-compliance on the intensive margin. An alternative way of modeling non-compliance would be to introduce heterogeneity in the cost or in the stigma of being caught not complying. This alternative formulation would introduce an extensive margin in tax evasion—i.e., whether to use the informal sector or not—but would lead to generally similar results. Of course, the most general approach would consider both margins and allow for heterogeneous effects according to economic circumstance, e.g., greater difficulties in measuring the value of labor earnings by owner-cultivators, the values of own production, or the value of bartered exchange in some sectors of the economy.14

Costs of fiscal-capacity investments: There is a given period-1 level of fiscal capacity relevant to sector ![]() denoted by

denoted by ![]() and a level for period 2 denoted by

and a level for period 2 denoted by ![]() which is endogenously determined by costly investments. The investment costs across the

which is endogenously determined by costly investments. The investment costs across the ![]() tax bases

tax bases ![]() are:

are:

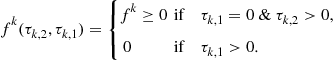

![]()

We assume that the first part of the investment-cost function ![]() is convex with

is convex with ![]() , i.e., the marginal cost at zero is negligible. There may or may not be a fixed-cost component, depending on whether the period-1 government inherits a fiscal capacity of zero for tax base

, i.e., the marginal cost at zero is negligible. There may or may not be a fixed-cost component, depending on whether the period-1 government inherits a fiscal capacity of zero for tax base ![]()

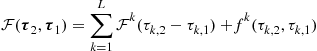

Let

be the total costs of investing in fiscal capacity. The separability of the cost function across tax bases is made for analytical convenience. Another feature of the technology is that it does not depend on the wage rate, even though it could be that investing in fiscal capacity costs more in a more productive economy.

In practical terms, the costs of fiscal-capacity investment are more obvious for some tax bases than others. For example, levying an effective income tax requires a collection system with trained inspectors, some kind of record keeping, and the ability to cross check. We would thus expect a relatively large fixed-cost component, i.e., ![]() for

for ![]() . Equally, a VAT system requires an ability to monitor and verify the use of inputs and the value of sales for all goods simultaneously (but the VAT does not directly fit the framework above). Levying border taxes usually takes place by monitoring ports and airports to measure trade flows. For such taxes, we would expect the fixed-cost component to be small or absent. Moreover, inspecting trade flows is easier for volumes than values, which might explain why so many border taxes are specific rather than ad valorem.

. Equally, a VAT system requires an ability to monitor and verify the use of inputs and the value of sales for all goods simultaneously (but the VAT does not directly fit the framework above). Levying border taxes usually takes place by monitoring ports and airports to measure trade flows. For such taxes, we would expect the fixed-cost component to be small or absent. Moreover, inspecting trade flows is easier for volumes than values, which might explain why so many border taxes are specific rather than ad valorem.

However, in all these cases, public resources need to be devoted to monitoring and compliance. Below, we will discuss in greater detail different options for introducing new technologies to improve compliance.

Household decisions: Preferences are quasi-linear and given by:

![]()

where ![]() is a concave utility function and

is a concave utility function and ![]() is the convex disutility of labor. The utility of public goods is partly described by concave function

is the convex disutility of labor. The utility of public goods is partly described by concave function ![]() . We use

. We use ![]() to parametrize the value of public goods, which we allow to be group and time specific. The individual budget constraint is:

to parametrize the value of public goods, which we allow to be group and time specific. The individual budget constraint is:

In this expression, ![]() is a group-specific cash transfer.15 The only non-standard feature is the last term, namely the total “profit” from reducing tax payments. What makes this formulation of the household problem simple is the fact that tax incidence and behavior are still governed by the statutory tax rates as long as

is a group-specific cash transfer.15 The only non-standard feature is the last term, namely the total “profit” from reducing tax payments. What makes this formulation of the household problem simple is the fact that tax incidence and behavior are still governed by the statutory tax rates as long as ![]() .

.

Maximizing the consumers’ utility yields a vector of commodity demands and labor supply which is quite conventional. Commodity demands are the same for all groups ![]() . This is because preferences for private goods are the same and there are no income effects on taxed commodities.

. This is because preferences for private goods are the same and there are no income effects on taxed commodities.

For the tax bases where the government has some fiscal capacity, ![]() , the decisions to reduce the tax burden, which we assume have an interior solution,16 are also equal across groups, and implicitly defined by

, the decisions to reduce the tax burden, which we assume have an interior solution,16 are also equal across groups, and implicitly defined by

![]() (1)

(1)

It is straightforward to see that the convexity of the cost function makes equilibrium evasion ![]() decreasing in the fiscal capacity investment, tax base by tax base. The household profits from such activities are:

decreasing in the fiscal capacity investment, tax base by tax base. The household profits from such activities are:

![]()

which are increasing in ![]() and decreasing in

and decreasing in ![]() .17

.17

When there is no fiscal capacity, ![]() , any positive tax rate

, any positive tax rate ![]() would give us a corner solution with

would give us a corner solution with ![]() or

or ![]() . This is a case where all consumption could be sheltered from taxation in the informal sector where the individual has no tax liability. Thus, no tax income is raised at whatever level the statutory rate is set. We assume that in such cases the government sets the statutory tax rate at zero.

. This is a case where all consumption could be sheltered from taxation in the informal sector where the individual has no tax liability. Thus, no tax income is raised at whatever level the statutory rate is set. We assume that in such cases the government sets the statutory tax rate at zero.

Indirect utility: Let

be the aggregate (equilibrium) per-capita profit from efforts devoted to tax-reducing activities where ![]() is the vector of tax rates.

is the vector of tax rates.

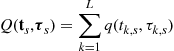

The indirect utility function for group ![]() becomes:

becomes:

(2)

(2)

The first term on the right-hand side is the private surplus from the consumption of goods ![]() . The separable, quasi-linear preferences make the private surplus additively separable in goods and labor—hence the second term. A convenient, but special, feature of the setup is that the gains from tax reduction are not group specific—hence the third term is not indexed by group. These features help make the analysis much simpler but do not compromise the economic insights. They could all be relaxed, albeit with increased complexity.

. The separable, quasi-linear preferences make the private surplus additively separable in goods and labor—hence the second term. A convenient, but special, feature of the setup is that the gains from tax reduction are not group specific—hence the third term is not indexed by group. These features help make the analysis much simpler but do not compromise the economic insights. They could all be relaxed, albeit with increased complexity.

The policy problem: Governments choose tax rates on all goods and labor and a spending policy, dividing the tax proceeds between public goods, transfers, and investments in fiscal capacity.

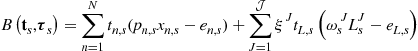

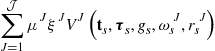

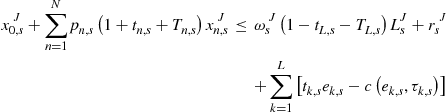

Let

be the tax revenue from goods and labor, where the expression in the first sum relies on the fact that all groups choose the same consumption vector for non-numeraire goods. This is not true for labor supply, however, if different groups have different wage rates. The government budget constraint becomes

(3)

(3)

where

is the amount invested in fiscal capacity (relevant only in period 1) and ![]() is any (net) revenue from borrowing, aid, or natural resources.

is any (net) revenue from borrowing, aid, or natural resources.

We now go on to consider, first, how a government will set taxes and spending and, then, how it will choose to invest in fiscal capacity. Thus, we begin by studying the static (within-period) problem taking fiscal capacity as given.

The social objective of the government has fixed weights ![]() , one for each group, which are normalized so that

, one for each group, which are normalized so that ![]() . Then the government maximizes:

. Then the government maximizes:

subject to (3). This is a more or less standard optimal-tax cum public-goods problem, along the lines first studied in Diamond and Mirrlees (1971). It is special only in that we have assumed quasi-linear utility and added the possibility of tax evasion.

Optimal taxation: Taxes will follow a standard Ramsey-tax rule, except for the fact that taxes affect non-compliance decisions, as well as consumption and labor supply decisions. To state the tax rules, define the effective tax bases:

(4)

(4)

where ![]() and

and ![]() are per-capita commodity demands and (group-specific) labor supplies. The additive separability of the utility function makes the effective income tax base a function of the income tax alone. With this notation, the Ramsey-tax rule for commodities is

are per-capita commodity demands and (group-specific) labor supplies. The additive separability of the utility function makes the effective income tax base a function of the income tax alone. With this notation, the Ramsey-tax rule for commodities is

where ![]() is the value of public funds. Given the possibility of reducing the tax burden, it is the demands net of avoidance

is the value of public funds. Given the possibility of reducing the tax burden, it is the demands net of avoidance ![]() and the behavioral response of these taxable net demands that shape the tax rates.

and the behavioral response of these taxable net demands that shape the tax rates.

For those goods where there is no fiscal capacity, the government (by assumption) sets taxes at zero. Moreover, we focus on the natural case where ![]() whenever

whenever ![]() . This says that, if the government has any fiscal capacity in some tax base, there is a non-trivial level of non-compliance. In this case, we also expect that the optimal-tax rate will be positive for any tax base where

. This says that, if the government has any fiscal capacity in some tax base, there is a non-trivial level of non-compliance. In this case, we also expect that the optimal-tax rate will be positive for any tax base where ![]() .

.

The optimal income tax solves:

where ![]() is weighted net taxable labor income allowing for heterogeneous wages. The optimal-tax expression is similar to the optimal commodity tax in that it involves the total behavioral response of the tax base

is weighted net taxable labor income allowing for heterogeneous wages. The optimal-tax expression is similar to the optimal commodity tax in that it involves the total behavioral response of the tax base ![]() . However, the income transferred from citizens to government (the first term) is weighted by the social objective. In general, this term depends on the correlation between the group weights

. However, the income transferred from citizens to government (the first term) is weighted by the social objective. In general, this term depends on the correlation between the group weights ![]() and wages

and wages ![]() across groups.

across groups.

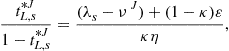

To illustrate how the lack of fiscal capacity to enforce income taxes affects choices, let us assume that wages are the same for all groups, ![]() . In this case, the optimal income tax rate solves:

. In this case, the optimal income tax rate solves:

![]() (5)

(5)

where

![]()

is the elasticity of labor supply with respect to the (net of tax) after-tax wage,

![]()

is the elasticity of evasion with respect to the income tax rate and

![]()

reflects the extent of non-compliance. The standard optimal income tax formula has ![]() so only the labor-supply elasticity

so only the labor-supply elasticity ![]() and the value of public funds

and the value of public funds ![]() , to be spent on public goods or transfers, determine the optimal tax. In that case,

, to be spent on public goods or transfers, determine the optimal tax. In that case, ![]() above 1 is sufficient for the optimal-tax rate to be positive.

above 1 is sufficient for the optimal-tax rate to be positive.

With non-compliance, however, the optimal-tax rate is lower all else equal. To see this, observe that, using Eq. (5),

![]()

So any factor which makes it easier to avoid paying taxes or increases the extent of avoidance depresses the incentive to use the income tax. Thus, we would expect lower rates of taxation, as well as lower collection of taxes for a given rate, in jurisdictions, and times with little investment in fiscal capacity for tax collection (insofar as fiscal capacity decreases ![]() and

and ![]() ).

).

The optimal-tax formulas above reflect that, when citizens can reduce their tax liability, taxes raise less revenue than otherwise. The total behavioral response to taxation can, in principle, be larger or smaller than in the absence of tax avoidance, depending on the sensitivity of such activity to a higher tax rate. And these responses will be influenced by investments in fiscal capacity.

There is a direct link here to the literature on taxable income elasticities and which elasticity is the right sufficient statistic for welfare-relevant behavioral responses—see Chetty (2009). Define

![]()

as the taxable income elasticity with respect to the after-tax rate. Then, (5) can be written as

![]()

Thus, the taxable income tax elasticity is the right sufficient statistic for all behavioral responses for the model that we are using.18 These considerations should be applied to all tax bases, not just to labor income. In many countries’ compliance with the VAT is a big issue and the taxable demand elasticity would be relevant to understanding tax policy.

As things stand, the collection of evidence regarding the total response of tax revenues to tax rates, and the sources of these effects, is only in its infancy for developing countries. This is true even for income taxes, the area where most progress has been made in the developed country literature. An important exception are the findings of Kleven and Mazhar (in press), who estimate taxable income elasticities for Pakistan using detailed administrative data, and find these elasticities to be quite small, at least among those who are already registered to pay income taxes. To collect more micro-data, and use administrative records where they exist, to improve knowledge of behavioral responses to income taxation in developing countries, and to understand how the responses relate to alternative compliance structures, is a very important topic for future research.

The analysis in this section suggests that to understand the fiscal facts about developing countries laid out in Section 3, we may be able to appeal to the fiscal-capacity investments that shape total behavioral responses to taxation through standard consumption and labor-supply distortions but also through compliance decisions. The observed structure of taxes reflects that low or non-existing fiscal capacity makes it difficult to collect statutory taxes for some tax bases. This is particularly true when we compare income taxes to trade taxes, with the latter being less demanding in terms of fiscal-capacity investments. A low tax take may thus not reflect large distortions in consumption and labor supply, for any given tax system, but large opportunities for non-compliance. Hence, our emphasis on fiscal-capacity investments is given below.

Optimal public spending: Before turning to fiscal capacity, we briefly deal with public spending. In this dimension, the government decides how much revenue to allocate to transfers and public goods, respectively. With quasi-linear utility, an unconstrained government will direct all transfer spending, if any, to the group with the highest “welfare weight”, ![]() . This is, of course, a stark and unrealistic prediction (but in Section 5.2 we introduce political constraints that potentially bring about more equal sharing). In the special Utilitarian case, where

. This is, of course, a stark and unrealistic prediction (but in Section 5.2 we introduce political constraints that potentially bring about more equal sharing). In the special Utilitarian case, where ![]() for all

for all ![]() , we can assume without loss of generality that any transfer spending is spent equally. Let

, we can assume without loss of generality that any transfer spending is spent equally. Let ![]() .

.

To define the optimal level of public spending, let ![]() be total tax revenue when taxes are set optimally and the marginal value of public funds is

be total tax revenue when taxes are set optimally and the marginal value of public funds is ![]() . There are two cases. If

. There are two cases. If

then all spending will be allocated to public goods, i.e.,

This is a case where public goods are very valuable and/or tax revenue is scarce.

In the other case, the marginal value of public funds is ![]() , tax revenues are

, tax revenues are ![]() , public goods have an interior solution, and the remaining revenue is spent on transfers to the group defining

, public goods have an interior solution, and the remaining revenue is spent on transfers to the group defining ![]() .

.

Investments in fiscal capacity: The main novelty in our approach to taxation and development is to study purposeful and forward-looking decisions by government to invest in alternative forms of fiscal capacity, i.e., in vector ![]() . We now study this investment decision when

. We now study this investment decision when ![]() is endogenous and chosen by the government in period 1. The next section will then use the results to evaluate which forces drive the creation of fiscal capacity and how these relate to economic, political, and social development.

is endogenous and chosen by the government in period 1. The next section will then use the results to evaluate which forces drive the creation of fiscal capacity and how these relate to economic, political, and social development.

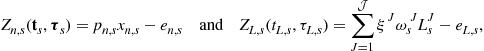

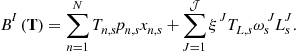

Let

(6)

(6)

be the maximized value of the government’s payoff. Implicit in this payoff are the optimal tax and spending vectors for each level of the fiscal-capacity constraints.

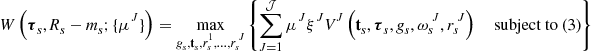

The fiscal-capacity investment decision amounts to choosing ![]() to maximize:

to maximize:

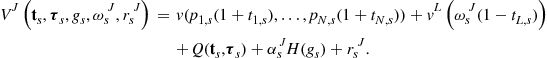

![]() (7)

(7)

This yields a series of conditions for creating fiscal capacity, or investing in it once it has been created.

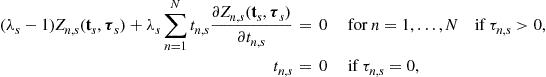

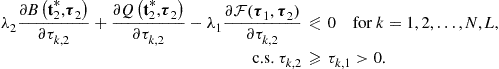

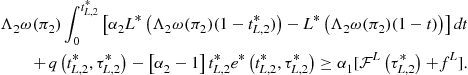

For fiscal capacity already in existence, i.e., ![]() , we have standard first-order conditions in a convenient and readily interpretable form. Using the envelope theorem to eliminate terms in optimal government (and private) choices, these first-order conditions can be written as:

, we have standard first-order conditions in a convenient and readily interpretable form. Using the envelope theorem to eliminate terms in optimal government (and private) choices, these first-order conditions can be written as:

(8)

(8)

Three terms govern the investment decisions. The first is the added revenue from better fiscal capacity, weighted by the period-2 marginal value of public funds. The second term in (8) is the marginal cost imposed on citizens by higher fiscal capacity—essentially due to higher tax payments, as the profits from non-compliance fall when fiscal capacity is higher. The third term is the marginal cost of investing, weighted by the period-1 marginal value of public funds.

The three terms in Eq. (8) nicely encapsulate the forces that shape fiscal-capacity decisions. First, some factors make future revenue more valuable (cost of public funds ![]() and the revenue function

and the revenue function ![]() )—these will have a disproportionate effect on investment in tax bases, which are not very elastic. Second, some circumstances shape the utility cost of taxation, which depend on the lengths governments have to go to increase compliance (the profit function

)—these will have a disproportionate effect on investment in tax bases, which are not very elastic. Second, some circumstances shape the utility cost of taxation, which depend on the lengths governments have to go to increase compliance (the profit function ![]() ). Third, some features of the economy make it more or less expensive to invest—including a high current marginal cost (the cost function

). Third, some features of the economy make it more or less expensive to invest—including a high current marginal cost (the cost function ![]() and value of public funds

and value of public funds ![]() ). The investment cost could be quite specific to some kinds of tax bases.

). The investment cost could be quite specific to some kinds of tax bases.

For the case where the government is thinking about introducing a new tax base, the reasoning is inherently non-marginal. Discrete gains or losses have to be weighed against the fixed cost of the investment. So consider a decision by a government to add a tax base ![]() where initially

where initially ![]() . This will give a discrete (non-marginal) change in indirect utility, which comes from changes in the use of existing tax bases as well as increased spending on public goods. It will also imply discrete changes in the profits from non-compliance with new tax base as the optimal taxes change. Together, these yield a discrete change in

. This will give a discrete (non-marginal) change in indirect utility, which comes from changes in the use of existing tax bases as well as increased spending on public goods. It will also imply discrete changes in the profits from non-compliance with new tax base as the optimal taxes change. Together, these yield a discrete change in ![]() —evaluated at the level

—evaluated at the level ![]() which solves (8)—that must be weighed against the cost of the investment

which solves (8)—that must be weighed against the cost of the investment ![]() . In general, this kind of non-marginal analysis is quite complicated. That said, the main economic forces identified in our discussion of (8) remain the salient forces to shape the decision to invest in new tax bases. In Section 5, we illustrate this for the specific case of introducing an income tax.

. In general, this kind of non-marginal analysis is quite complicated. That said, the main economic forces identified in our discussion of (8) remain the salient forces to shape the decision to invest in new tax bases. In Section 5, we illustrate this for the specific case of introducing an income tax.

Next steps: Having built an approach for studying investments in fiscal capacity, we will exploit it to gain insights into differences between different societies at a point in time and the same society at different points in time.

More specifically, Section 5 brings up six sets of factors pinpointed by our modeling approach. First, we study the effect of purely economic factors on the incentive to build a tax system. Second, we turn to the role of politics, asking how political instability and the structure of political institutions affect the choice of fiscal capacity. Third, we look at social structure, including inequality, heterogeneity, and polarization. Fourth, we study the demand side for revenue and the factors that determine the value of public spending. Fifth, observing that many poor states rely heavily on aid or natural resource rents, we explore how these non-tax income flows affect the incentives to build other kinds of fiscal capacity. Finally, we go into more detail on the technology for increasing tax compliance.

In all cases, we use the model developed in this section as a starting point. However, in each case it will prove convenient to specialize some features to home in on a particular issue.

5 Drivers of Change

5.1 Economic Development

In this subsection, we discuss how economic change affects choices of fiscal capacity and the implications for observed taxation. Against the background of the stark time-series and cross-sectional facts in Section 3, we focus on the role of economic development for the introduction and expansion of the income tax. As discussed at the outset, this has also been the standard focus in the taxation and development literature. We begin by discussing exogenous differences in the economy across countries or time, turning then to changes that are endogenous to the government’s investment in fiscal capacity.

Exogenous economic differences: We noted in Section 3 (recall Figure 4) the typical path of change involves the two discrete steps of introducing the income tax and upgrading its reach via direct withholding. In a contemporary cross-section, we also saw (recall Figures 7 and 8) that rich and high-taxing states rely much more on the income tax than poor and low-taxing states. Through which channels does our framework explain such patterns in the data?

To answer this question, we specialize the model to include only one consumption good, in addition to the numeraire good and labor—i.e., we set ![]() . Moreover, there is no fixed cost in building fiscal capacity for the taxable consumption good, whereas a fixed cost may exist for the income tax—i.e., we have

. Moreover, there is no fixed cost in building fiscal capacity for the taxable consumption good, whereas a fixed cost may exist for the income tax—i.e., we have ![]() and

and ![]() . Of course, this stark difference is for illustrative purposes only. To keep things simple and pin down the value of public funds, we specialize the utility function to be linear in public goods, i.e.,

. Of course, this stark difference is for illustrative purposes only. To keep things simple and pin down the value of public funds, we specialize the utility function to be linear in public goods, i.e., ![]() , and the value of public goods to be equal across groups exceeding the value of transfers, i.e.,

, and the value of public goods to be equal across groups exceeding the value of transfers, i.e., ![]() . These assumptions are relaxed in later subsections on politics and the value of public spending. For now, they allow us to focus on a government that spends only on public goods with a constant marginal value of funds.

. These assumptions are relaxed in later subsections on politics and the value of public spending. For now, they allow us to focus on a government that spends only on public goods with a constant marginal value of funds.

We start by assuming that wages are given by the simple expression

![]()

i.e., every group ![]() has the same wage. Different values of

has the same wage. Different values of ![]() could represent natural exogenous income differences across countries, or across time, due to, say, geography or total factor productivity.

could represent natural exogenous income differences across countries, or across time, due to, say, geography or total factor productivity.

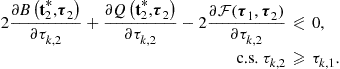

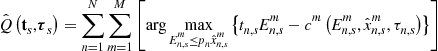

In this specialized framework, the marginal first-order conditions(8) associated with the two tax bases are

![]() (9)

(9)

![]()

If there were no fixed costs, this expression would tell us that the government invests more in the tax base that raises more revenue on the margin at the future value of public funds (the first term), induces a lower utility cost for consumers via the cost of tax evasion (the second term), or has a lower marginal cost of investing at the current value of public funds (the third term). Provided the positive first term outweighs the negative second term, for ![]() , we observe positive investments in both types of fiscal capacity since

, we observe positive investments in both types of fiscal capacity since ![]() .

.

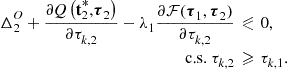

We now revisit the question of when an income tax is worth levying at all and why economic growth might typically induce the introduction of an income tax, as we have seen historically. Suppose fiscal-capacity building for the income tax has a fixed cost and the period-1 level of this capacity is zero, ![]() . Recall that the government raises no revenue at zero fiscal capacity. In order for the income tax to be introduced, the perceived welfare gains from doing so, by bringing fiscal capacity up to locally optimal level

. Recall that the government raises no revenue at zero fiscal capacity. In order for the income tax to be introduced, the perceived welfare gains from doing so, by bringing fiscal capacity up to locally optimal level ![]() given by (9), have to be large enough to outweigh the effective fixed cost

given by (9), have to be large enough to outweigh the effective fixed cost ![]() associated with setting up a compliance and monitoring system. Using the definitions and additive separability of the government payoff (6), the net tax bases (4), and the indirect utility function (2), and recalling that when

associated with setting up a compliance and monitoring system. Using the definitions and additive separability of the government payoff (6), the net tax bases (4), and the indirect utility function (2), and recalling that when ![]() we have

we have ![]() (private evasion cost and taxes are zero), we can write the formal condition as follows:

(private evasion cost and taxes are zero), we can write the formal condition as follows:

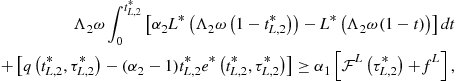

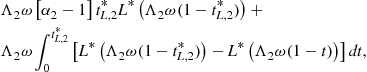

(10)

(10)

where ![]() solves (9).

solves (9).

There are three main considerations. The term on the first line reflects the value of transferring funds from private incomes to public spending, recognizing that lower labor supply induces a deadweight loss. This expression is positive only if ![]() is sufficiently high (above one).19 Also, the first-line term is proportional to exogenous productivity

is sufficiently high (above one).19 Also, the first-line term is proportional to exogenous productivity ![]() , as this determines how lucrative the income tax base is. The second term on the left-hand side reflects the possibility of non-compliance. It has two parts, the first reflecting the gain from a new source of profits from tax avoidance. However, this is offset by the fact that greater avoidance reduces valuable public spending. If there was full compliance at

, as this determines how lucrative the income tax base is. The second term on the left-hand side reflects the possibility of non-compliance. It has two parts, the first reflecting the gain from a new source of profits from tax avoidance. However, this is offset by the fact that greater avoidance reduces valuable public spending. If there was full compliance at ![]() , then this expression would be zero. Finally, the term on the right-hand side reflects the costs of introducing a new tax base—fixed costs and the cost of the investment in fiscal capacity up to

, then this expression would be zero. Finally, the term on the right-hand side reflects the costs of introducing a new tax base—fixed costs and the cost of the investment in fiscal capacity up to ![]() .

.

Notice that the tax base in the first term of (10) is increasing in the productivity factor ![]() . Moreover, the optimal income tax rate

. Moreover, the optimal income tax rate ![]() associated with a given level of fiscal capacity will generally be higher if income is higher. To see this, recall the Ramsey-tax formula (5), where

associated with a given level of fiscal capacity will generally be higher if income is higher. To see this, recall the Ramsey-tax formula (5), where ![]() is decreasing in

is decreasing in ![]() , and hence increasing in

, and hence increasing in ![]() (since

(since ![]() is decreasing in

is decreasing in ![]() ).

).

If ![]() captures income growth over time, this can naturally explain the eventual introduction of an income tax, as in Figure 4, by reference to (10). If

captures income growth over time, this can naturally explain the eventual introduction of an income tax, as in Figure 4, by reference to (10). If ![]() instead captures differences across countries, at a given point in time, this can explain the higher reliance of the income tax in rich and high-tax countries, as in Figures 7 and 8. To explicitly link up with the data on income taxes vs. trade taxes discussed in Section 3, the argument would have to be recast in a setting where trade rather than consumption is the alternative tax base (see Besley & Persson, 2011c, chap. 2 for such a model).

instead captures differences across countries, at a given point in time, this can explain the higher reliance of the income tax in rich and high-tax countries, as in Figures 7 and 8. To explicitly link up with the data on income taxes vs. trade taxes discussed in Section 3, the argument would have to be recast in a setting where trade rather than consumption is the alternative tax base (see Besley & Persson, 2011c, chap. 2 for such a model).

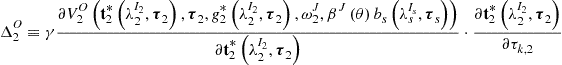

Endogenous economic differences: In this section, we make the level of fiscal capacity endogenous to other government decisions. The general modeling follows the analysis in Besley and Persson (2011c).

Let wages be given by ![]() , where scalar

, where scalar ![]() represents endogenous government investment to increase productivity and where

represents endogenous government investment to increase productivity and where ![]() is an increasing concave function. As Besley and Persson (2011c, chap. 3) show, one can microfound such a formulation if

is an increasing concave function. As Besley and Persson (2011c, chap. 3) show, one can microfound such a formulation if ![]() represents the capacity to carry out legal support to the private sector concerning contract enforcement or, alternatively, protection of property rights. In this interpretation, which we will maintain in this subsection,

represents the capacity to carry out legal support to the private sector concerning contract enforcement or, alternatively, protection of property rights. In this interpretation, which we will maintain in this subsection, ![]() captures the legal capacity of the government: its courts, its supply of educated judges, or its registers for credit or property. An alternative interpretation would be to think of

captures the legal capacity of the government: its courts, its supply of educated judges, or its registers for credit or property. An alternative interpretation would be to think of ![]() as government infrastructure that raises the productivity in the private sector. We could also let

as government infrastructure that raises the productivity in the private sector. We could also let ![]() be a vector of productive capacities, rather than a scalar.

be a vector of productive capacities, rather than a scalar.

Analogous to fiscal capacity, we assume that legal capacity in period 2 can be augmented by investment in period 1 at cost ![]() . We assume that legal-capacity investments have no fixed costs, for simplicity, and that

. We assume that legal-capacity investments have no fixed costs, for simplicity, and that ![]() is a convex function with

is a convex function with ![]() . As a consequence, the total investment costs for the period-1 government are now given by

. As a consequence, the total investment costs for the period-1 government are now given by

What happens to the investment in fiscal capacity in the specialized model that we just studied, when we replace exogenous wages ![]() with endogenous wages

with endogenous wages ![]() The marginal investment conditions in (9) are not affected, because neither

The marginal investment conditions in (9) are not affected, because neither ![]() nor

nor ![]() depend on legal-capacity investments

depend on legal-capacity investments ![]() . However, the condition for incurring the fixed costs of the income tax now becomes:

. However, the condition for incurring the fixed costs of the income tax now becomes:

(11)

(11)

Only the first term from (10) is affected with higher legal capacity increasing wages. There are good reasons to expect that this key expression is increasing in ![]() and

and ![]() . For example, in the case of a constant elasticity of labor supply,

. For example, in the case of a constant elasticity of labor supply, ![]() , the first expression in (11) becomes:

, the first expression in (11) becomes:

![]()

which is clearly increasing in ![]() . Thus, a country with higher legal capacity and endogenously higher income is more likely to have an income tax than one with low legal capacity.

. Thus, a country with higher legal capacity and endogenously higher income is more likely to have an income tax than one with low legal capacity.

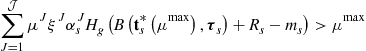

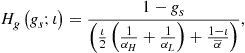

Of course, this raises the question what drives investments in legal capacity. Maximizing the investment objective (7) with regard to ![]() , under the assumptions of the specialized model and using Roy’s identity, we obtain the first-order condition

, under the assumptions of the specialized model and using Roy’s identity, we obtain the first-order condition

![]() (12)

(12)

Since the two terms in the first bracket, the net benefit of legal capacity, are both non-negative and since ![]() , there are always positive investments in legal capacity. Moreover, a higher level of fiscal capacity in the income tax

, there are always positive investments in legal capacity. Moreover, a higher level of fiscal capacity in the income tax ![]() raises the equilibrium tax rate

raises the equilibrium tax rate ![]() . This way, a higher value of

. This way, a higher value of ![]() raises the net benefit of investing in legal capacity, by raising the private marginal surplus from higher wages as well as boosting the fiscal benefits of the income tax through a higher tax base.

raises the net benefit of investing in legal capacity, by raising the private marginal surplus from higher wages as well as boosting the fiscal benefits of the income tax through a higher tax base.

This result and the earlier result, that a higher ![]() makes (11) more likely to hold, make the investment in legal capacity and the investment in fiscal capacity necessary to introduce the income tax complementary decisions. This is a close relative to the complementarity discussed in Besley and Persson (2009a,b, 2011a,b,c). Thus, the endogenous growth of income triggered by investments in the productive side of the state makes it more likely that a country at some point in time will incur the fixed costs necessary to put an income tax in place.

makes (11) more likely to hold, make the investment in legal capacity and the investment in fiscal capacity necessary to introduce the income tax complementary decisions. This is a close relative to the complementarity discussed in Besley and Persson (2009a,b, 2011a,b,c). Thus, the endogenous growth of income triggered by investments in the productive side of the state makes it more likely that a country at some point in time will incur the fixed costs necessary to put an income tax in place.

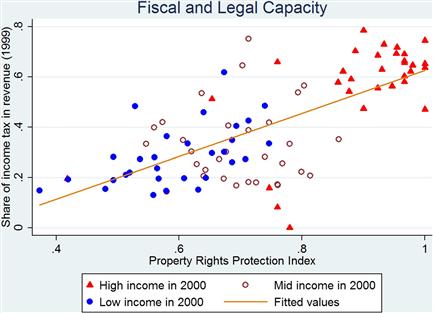

As discussed at length in this earlier work, measures of fiscal capacity—like a high share of total tax income collected by the income tax—and measures of legal capacity are strongly positively correlated across countries in the data, and both of these capacities indeed have a strong positive correlation with income.

This point is illustrated in Figure 12 which plots the share of income tax in total tax revenue in 1999 against the ICRG measure of property-rights protection. Countries that raise more in income tax (have more fiscal capacity) also tend to enforce property rights in a better way (have more legal capacity).

Structural change: Development is about a lot more than raising income per capita. The process of rising incomes typically goes hand in hand with structural change toward a more urbanized and non-agriculturally based economy. As a consequence, more economic activity operates in the open, particularly in the formal sector where transactions and employment relations are recorded. To some extent, informality in production is just the flip side of tax avoidance. But it is more than that. Firms also choose not to become part of the formal sector in order to avoid an array of regulations. But this has a cost: such firms are not able to take advantage of formal legal protection and contract disputes have to be resolved informally, often placing trust between parties at a premium. This limits the scope of business, which often becomes restricted to social networks.

The move toward formality tends to facilitate tax compliance. More employment takes place in legally registered firms rather than self-employment, as stressed by Kleven et al. (2009), and more financial transactions take place via formal intermediaries (such as banks), as stressed by Gordon and Li (2009). Both of these make transactions more visible to tax authorities and enable tax authorities to obtain corroborating evidence from cross-reported transactions. Falsifying these requires collusion rather than unilateral secrecy. Such changes result from transformations in the nature of economic activity whereby larger firms take advantage of scale economies in production. To the extent that this is reflected in higher wages, the arguments from the last section apply and we expect investments in fiscal capacity to occur.

The typical discussion of development and taxation couches structural change as an exogenous feature of economic development with causality running from economic development to fiscal capacity. This can be captured in our model either by allowing the function ![]() to depend on the sector of the economy in which an individual is operating. Suppose we exogenously assign individuals to the formal and informal sectors denoted by

to depend on the sector of the economy in which an individual is operating. Suppose we exogenously assign individuals to the formal and informal sectors denoted by ![]() where

where ![]() stands for “formal” and

stands for “formal” and ![]() for “informal” with evasion functions

for “informal” with evasion functions ![]() . We may then reasonably suppose that

. We may then reasonably suppose that

![]()

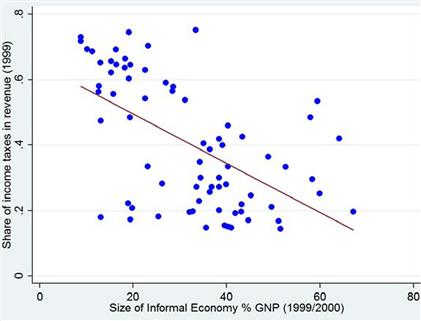

i.e., the marginal impact of an investment in fiscal capacity is more effective in deterring evasion for those operating in the formal sector. In this event, more formality would boost the revenues that can be generated from fiscal-capacity investments, all else equal. This is consistent with the observation that countries with smaller informal sectors also raise more taxes. This is illustrated in Figure 13 which plots a measure of the size of the informal economy in 1999/2000 from Schneider (2002) against the share of income taxes in total tax revenue in 1999 from Baunsgaard and Keen (2005). The downward sloping relationship is extremely clear.

The literature has paid less attention to the possibility that the size of the informal sector and the structural development of the economy evolve endogenously with the development of fiscal capacity, as in our discussion of legal capacity above. However, we may also take a further step and think of legal capacity as affecting the returns to being formal. It is very hard for an individual to simultaneously be largely invisible to the tax system and take full advantage of the formal legal system. This creates a further complementarity between the legal and fiscal capacities of the state. A state which invests in the infrastructure to support formal financial intermediation will overcome some of the barriers to formality and enhance the ability to raise more taxes. A good example are efforts to build credit and land registries in the process of development, to increase property rights and contract enforcement. Such registries bring the patterns of ownership and credit contracts into the daylight for tax authorities. To study these issues explicitly, we would have to extend the model with an endogenous decision to choose the sector ![]() based on costs and benefits. While a higher cost of tax evasion is a cost of choosing the formal sector, there may be benefits in the form of a better trading environment.20

based on costs and benefits. While a higher cost of tax evasion is a cost of choosing the formal sector, there may be benefits in the form of a better trading environment.20

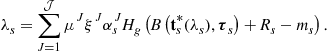

5.2 Politics

No account of the development process can be complete without considering the political forces that shape policy selection. It is widely held that the failure of states to build strong institutions might reflect weak motives embedded in political institutions. In this section, we explore the implications of introducing a government which operates under institutional constraints and faces the possibility of political turnover. The specific framework that we use is based on Besley and Persson (2010a,b, 2011a,b,c). This belongs to a wider body of work and thinking in dynamic political economics which is reviewed in Acemoglu (2006). As we shall see, this adds new issues to the analysis of fiscal-capacity building and allows us to uncover additional forces which can explain high or low investments.

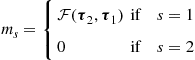

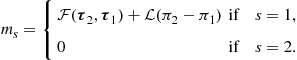

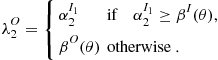

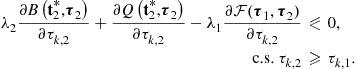

Cohesive institutions: Suppose the government in power acts on behalf of a specific group in the spirit of the citizen-candidate approach to politics—see Besley and Coate (1997) and Osborne and Slivinsky (1996). There is no agency problem within groups: whoever holds power on behalf of a group cares only about the average welfare of its members.

We model how political institutions constrain the incumbent’s allocation of transfers in a very simple way. Specifically, the incumbent group in period ![]() , called

, called ![]() , must give (at least) a fixed share

, must give (at least) a fixed share ![]() to all non-incumbent groups

to all non-incumbent groups ![]() for any unit of transfers awarded to its own group. That is to say, we impose the restriction

for any unit of transfers awarded to its own group. That is to say, we impose the restriction

![]()

The parameter ![]() represents the “cohesiveness” of institutions with

represents the “cohesiveness” of institutions with ![]() closer to

closer to ![]() representing greater cohesiveness.

representing greater cohesiveness.