Chapter 12

Global Supply Chain Management

![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the global supply chain environment and identify key impact factors.

- Explain market and cultural challenges that impact global supply chains.

- Describe global infrastructure challenges and role of technology.

- Identify key cost and non-cost considerations in managing global supply chains.

- Describe key political factors and non-tariff barriers that impact global supply chain management.

![]() Chapter Outline

Chapter Outline

- Global Supply Chain Management

The Global Environment

Opportunities and Barriers

Factors Impacting Global Supply Chains

- Global Market Challenges

The Global Consumer

Global Versus Local Marketing

Cultural Challenges

- Global Infrastructure Design

Infrastructure Challenges

Labour

Transportation

Suppliers

Role of Technology

- Cost Considerations

Hidden Costs

Non-Cost Considerations

- Political and Economic Factors

Impact of Exchange Rate Fluctuations

Regional Trade Agreements

Impact of Non-Tariff Barriers

- Chapter Highlights

- Key Terms

- Discussion Questions

- Case Study: Wú's Brew Works

Today India represents the second fastest growing economy in the world. It has an expanding consumer market, a burgeoning middle class, and a growing young and highly educated population. In fact, a 2005 A.T. Kearney global survey rated India as the greatest consumer market opportunity. For that reason many multinational companies are setting up their supply chains in India. Consider that PepsiCo Chief Executive Officer Indra Nooyi, herself born in India, says she will invest “aggressively” in this emerging market. Retail sales of the company's products in India, including Frito-Lay potato chips, Quaker Oats, and fruit juices, totaled $1.5 billion in 2009. Other companies are also positioning themselves for this rapidly growing market hungry for outside products. However, this opportunity also presents numerous challenges typical of managing global supply chains. Let's look at just a few of the issues involved in developing a distribution network in India.

Warehousing. Warehousing, needed to store goods, is complicated in India. Most existing warehouses in India are small in size, have dirt rather than cement floors, and little in the way of technology or material handling. Many distribution facilities are housed in structures that were designed for other purposes. For example, one of the largest pharmaceutical distributors in Mumbai runs a warehouse out of the third floor of an apartment building. There are also land acquisition issues. Even the influential domestic automaker Tata Motors had trouble getting land for a planned factory in West Bengal. To obtain the 997 acres required, the company had to work with the state government to consult with 13,000 farmers and pay them either for their land or the rights to use their land. The farmers then protested that their compensation was too low and that some of them were being forced to sell their land. The automaker finally shifted construction to another, less hostile region of the country. Even big domestic retailers, such as Reliance Retail Ltd., have had similar problems. All this means that a company going into India should consider partnering with a third-party logistics (3PL) provider that already has a warehouse or land on which it can build a facility.

Labor. Although labor is cheap in India, finding the right skills is much more complicated than expected. The largest market for logistics consulting services in India is not for designing warehouses. Rather, it is for helping teach people how to operate them. The skill gap between educated and uneducated people is much greater in India than it in the West. As a result, U.S. companies doing business in India cannot simply follow the common practice of recruiting warehouse personnel from the less educated tiers of society to save money. For example, some concepts and equipment considered basic to business, such as computers, are totally alien to the uneducated segment of the Indian population. For that reason it makes more sense to hire college-educated personnel, even though they may be more costly. Also, the Indian culture has historically emphasized hierarchies, which can be inhibiting to Western companies used to an open decision making style. Young and educated workers are more willing to adapt to this style.

Transportation. Transportation is yet another obstacle in India. When building a distribution network, one must consider slow transit networks and insufficient infrastructure. For example, 70% of India's seaborne trade is handled by just two of the country's 12 major ports. The rail system is also constrained when it comes to freight movements. Historically, the country's rail capacity was restricted to passenger traffic and only recently has the Indian government begun to promote rail shipments. Most commercial shipments in India are made by truck. However, the country has no large national transportation companies and most are small trucking companies. Transit times are slow and unpredictable compared to those in Western countries. Also, technology that often is used in the West is not yet common in India. Few truck drivers have cell phones that can be used to call in shipment status, and global positioning systems (GPS) are virtually nonexistent.

These are just some of the many supply chain roadblocks companies need to consider if they want to gain a foothold in India, and other emerging markets. It can take years to set up a distribution network due to the complexities. However, companies will find ways to overcome them for the opportunity to serve the world's second fastest growing economy.

Adapted from: “Now's the Time for an Indian Strategy.” Supply Chain Quarterly, Quarter 1, 2009: 28–33.

GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT

THE GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT

All organizations today operate in a global environment and are affected by global trade. Even the smallest of rural farms are affected by the global influx of foreign goods and trade regulations. Many companies serve multiple global markets, with products sourced and produced across many continents. Wal-Mart, the world's largest retailer, operates 8,500 stores in 15 countries, under 55 different names. Other multinational companies such as IBM, General Electric, Siemens, and McDonald's have a similar global reach. It is not uncommon for a company to develop a product in the United States, manufacture it in Asia, and sell it in Europe.

The rapid growth of globalization and international trade are a result of advanced transportation and information technology that have connected us across the globe, as well as a rise in personal income creating a heightened ability to buy. These forces have combined to create a global awareness and a demand for goods that translates into opportunities for companies to rapidly expand their markets.

The global trend will only continue in the future. Consider that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced that the global economy had grown faster than expected in 2010, and is predicted to grow by 4.8% per year in the future. Currently China represents the fastest growing global market, followed by India. In recent years, with most of the growth coming from developing country markets it makes sense for operations executives to target those markets for future growth. According to McKinsey & Co., Asia currently accounts for 40% of the global GDP, and will account for over 50% by 2025. However, emerging markets and competition in countries such as Malaysia, Singapore, and Brazil are on the rise. All this is resulting in a changing global landscape and increased competition.

For you as a consumer this means greater access to a variety of goods across the globe at competitive prices. However, what does this mean for companies and their supply chains? It means intensified and accelerated competitive pressures at all levels. It also means changes in the nature of competition. Companies that take on a global presence focus on challenges of entering markets in other countries, while their own markets are being opened to foreign competitors. This creates multiple levels of competition—one strategy for competing in new markets, with another strategy to guard the home turf. Companies need to prepare themselves to compete in this new environment.

In principle conducting global trade is not different from domestic trade as they both require coordinating supply chain management activities. The primary difference, however, is that global supply chain management involves a company's worldwide focus, including diverse and globally scattered markets, production facilities, and suppliers, rather than a local orientation. It requires a well-planned, designed, and managed supply chain network. This translates into large coordination complexities and risks, which companies need to balance against the opportunities and benefits presented by global markets. Just consider the complexities of global product distribution of a soft-drink beverage. In the United States, beverages are sold by the pallet via warehouse stores. In India and Southeast Asia, this is not an option and not all cultures use vending machines. In the United States a high-end product would not want to be distributed via a “dollar store.” By contrast, in France a product promoted as the low-cost option would easily find some success in a pricey boutique.

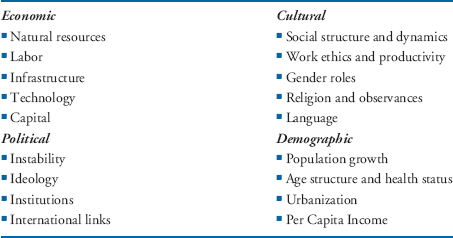

FIGURE 12.1 Global environmental factors.

Managing global supply chains is complicated by the fact that there are numerous environmental factors that must be considered. These factors fall into four categories: economic, cultural, political, and demographic, and are shown in Figure 12.1. They present both opportunities and barriers for going global and must be considered carefully. Local operations cannot simply be copied and placed globally, as Wal-Mart found out with their unsuccessful attempt at operating in Germany a few years earlier. Local culture must be well understood. We look at these challenges in a bit more detail in the next section.

SUPPLY CHAIN LEADER'S BOX— CHALLENGES OF GLOBAL CULTURE

Wal-Mart

In 1998, Wal-Mart moved into Germany, hoping to repeat its U.S. success in the Europe's largest economy. Unfortunately things did not turn out as Wal-Mart expected, forcing the company to close operations in Germany in 2006. The biggest mistake Wal-Mart made was to assume it could directly apply its American approach to business to a very different culture and business environment.

The mistakes Wal-Mart made included not understanding the market, the culture, tradition, and even labor laws. For example, Wal-Mart didn't know that American pillowcases are a different size than German ones, resulting in Wal-Mart Germany ending up with a huge pile of pillowcases they couldn't sell to German customers. Also, many German shoppers did not like having their purchases bagged by others. Similar misunderstandings occurred in the work environment as Wal-Mart's American managers pressured German executives to enforce American-style management practices in the workplace. For example, employees were forbidden from dating colleagues in positions of influence, and workers were also told not to flirt with one another. The company even attempted to introduce a telephone hotline for employees to inform on their colleagues, later ruled against by a German court. Other issues included high labor costs, as well as workers who tried to resist management's demands which they felt were unjust. At one point management threatened to close certain stores if staff did not agree to work longer hours than their contracts foresaw and did not permit video surveillance of their work. As a result, Wal-Mart Germany had several run-ins with the trade union that represents retail store workers.

Wal-Mart's retreat from Germany cost the company about $1 billion and is a lesson for all companies that they must tailor their operations to local cultures and tradition when going global. For companies to be successful in a foreign market they have to know their customers and local culture well. They cannot simply force a business model that worked well elsewhere onto another country's market.

Adapted from: Norton, Kate. “Wal-Mart's German Retreat.” Bloomberg Businessweek, July 28, 2006.

OPPORTUNITIES AND BARRIERS

Global reach is critical to a firm's survival. Without going global companies would be limited to just the goods and services produced within their own borders. Also, multinational firms are typically more profitable and grow faster than their domestic counterparts. Being global provides opportunities to tap into huge and growing markets, capitalize on new economic trends, and utilize technological innovations in other parts of the globe. It also enables utilizing natural resources available in other geographic areas.

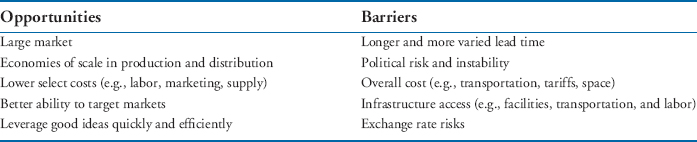

Developing a global supply chain network enables companies to achieve economies of scale in production and distribution in specific regions. Being closer to their respective markets, companies can implement good ideas quickly, and can target their marketing to local tastes. However, as seen in the chapter opener, there are numerous barriers that must be overcome when going global, listed in Figure 12.2.

FIGURE 12.2 Global considerations.

Trade on a global, or international, scale is considerably more complicated than domestic. Movement across borders, and even continents, adds numerous additional costs such as tariffs and extends the length and variability of lead time. There are time costs due to border delays, costs of transportation, and higher inventory costs due to longer transit times. There are also operational costs involved in conducting business in a different part of the world. This includes differences in labor productivity and access to labor skills, access to transportation and infrastructural support, as well as availability of technology. As seen in the case of Wal-Mart, companies often overlook the cultural impact and traditions, as well as the legal and political differences. There are also significant risks that include political instability, as well as currency fluctuations. All these factors compound across multiple regions adding to the complexity.

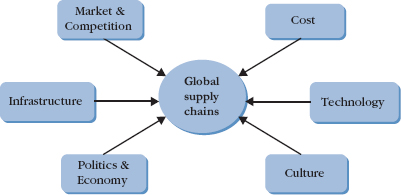

FACTORS IMPACTING GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAINS

The global environment is extremely dynamic. To compete, companies must constantly assess the global landscape. They must continuously identify new markets, anticipate competition and evaluating costs, and adjust their strategies accordingly. There are six significant factors that companies must monitor through out the process of managing their global supply chains. They are: market and competition, cost, infrastructure, technology, political and economic environment, and culture, and are shown in Figure 12.3. Although each of these factors will not affect every industry in the same way at the same time, each factor is an important consideration. It is important for companies to always be assessing these factors and proactively reacting to them for competitive positioning. Collectively these factors comprise a conceptual framework for managing global supply chains.

Market and competition are all factors involved in marketing and selling to global markets, including considering customer preferences and competition. Customer preferences and expectations are often unique in different global regions. Companies must find ways to compete in these respective markets, whether on price, cost, or innovation. They must then develop global supply chains that enable this type of competition.

FIGURE 12.3 Factors impacting global supply chains.

Cost is often the most cited reason by companies for going global. Often companies only consider individual costs, such as low direct labor cost, marketing cost, or perhaps local supplier cost. However, it is important for companies to consider total supply chain costs when going global. These include costs of quality, differential productivity and design costs, as well as added logistical and transportation costs.

Infrastructure availability enables the development and functioning of the supply chain network. This includes access to roads and transportation, equipment and communication networks, distribution systems, and skilled labor. Companies developing global supply chains are often surprised as to the lack of infrastructure in developing countries. This is typically one of the biggest global challenges. The ability to penetrate global markets depends on having global facilities and distribution and supply networks to respond to customer demands.

Technology significantly reduces time and distance, enabling global coordination and communication. Without technology global supply chains would not be able to operate. Technology enables manufacturing innovation that allow for more efficient means of changing the product mix and the ability to serve different markets. Information technology, in particular, enables information sharing and collaboration across the globe. Examples of this are availability of bar code technology, GPS, EDI, and RFID, that all enable global product tracking and communication.

Politics and economy include government regulation, political stability, formation of trade agreements, and currency fluctuations. Consider the impact on supply chain management when Europe passed environmental regulation making manufacturers responsible for returning product-packaging materials from customers. This regulation resulted in the design of entire networks for managing reverse flows of waste packaging.

Culture refers to acceptable behaviors, beliefs, and norms characteristic of a particular global region. This includes social structures and acceptable interactions, work ethic, observances and manners, gender roles, and adherence to formal chains of authority. Recall Wal-Mart's experience in Germany regarding applying the American policy of employee behavior or shoppers not wanting others to bag their purchased items.

GLOBAL MARKET CHALLENGES

Companies are attracted to global markets due to the potential size of the product market, providing a company with growth and profitability. However, global markets pose a number of challenges. One challenge is identifying customer preferences in globally diverse regions. This is especially difficult as customers across the globe increasingly want customization. This can result in huge product variety that may be impossible to deliver. Another challenge is deciding how to tailor marketing strategies to fit a variety of environments and customer behaviors. Competing globally requires developing a deep knowledge of global markets and competition, as well as local traditions. Foreign markets differ culturally and marketing or promotional strategies may have to be modified to meet local needs.

THE GLOBAL CONSUMER

Serving global markets means meeting the needs of the global consumer. The profile of the global consumer has changed over the recent years with a greater emphasis on individualism. Consumers everywhere have higher expectation that companies are going to meet their own individual needs and expectations. This may be customized clothing or unique service expectations. As a result businesses are redesigning their operations and supply chains to increasingly move from standardization to customization.

This new profile of the global customer has significant implications for business. The reason is that it explodes the number of possible combinations of product features. Coupled with today's expectations of fast delivery this can wreak havoc on a company. This means that firms must get their products to markets faster to gain a competitive advantage. This also means moving the product quicker through the design stage, through production, and then distribution. This typically requires logistics, operations, and distribution to be organized using lean systems in order to get the products to customers quickly. At the same time, however, the system must maintain flexibility in order to be able to produce different types of products with varying quantities. This can be quite an operational challenge.

GLOBAL VERSUS LOCAL MARKETING

There are two different marketing approaches that can be used when developing a global strategy. One is a global marketing approach that focuses on bringing standardization to the global market. The other is a local marketing approach that stresses micro-segmentation and localized differentiation. These approaches are contradictory, but they are best used to complement one another when developing a global strategy. One approach may dominate based on the specific demands of each product and market.

The global marketing approach assumes that there are consumers across the globe with identical needs, resulting in product standardization. The role of marketing here is to identify these consumers and the product characteristics they want. Coca-Cola is a good example of a company that has adopted a global marketing strategy. Although Coca-Cola produces many different beverages for the global market, its primary product remains unchanged. Maintaining product standardization provides many advantages for supply chain management, such as providing uniformity for distribution, sourcing, and packaging. It also makes it easier to balance supply and demand. However, uniformity in product standardization also provides challenges when implemented globally. A consistent and standardized product offered across the globe requires consistency in all global operations. This can be difficult to achieve as there are large variations in logistics, sourcing, and operations capabilities in different geographical locations. To maintain a reputation of product consistency these capabilities must be uniformly effective, regardless of the location. For example, if a company wants to compete on offering fast and reliable parts distribution service it must ensure it has the physical capability to provide the same service at all locations.

In contrast to global marketing, the local marketing approach focuses on micro-segmentation of customers and products. With the global customer increasingly demanding individuality, local marketing is becoming more important. The important part here is to judiciously segment the market so that it can take on a more national or regional characteristic, and that the regions are relatively homogenous. A localized marketing approach to international business adds significant complexity to a global system. Market segments quickly multiply based on the segmentation. Companies must then ensure that they have the infrastructure to reach and serve the customers in these segments around the world.

The best way, if possible, is to merge global and local marketing approaches. Coca-Cola has done this effectively. The company has 3,300 different products that it sells in over 200 countries. One strategy for achieving this is to use product postponement in the product design. Recall that product postponement is a strategy where the product is kept in the most generic form as long as possible in the distribution process. The product is differentiated at the last minute depending on the product and quantities at the location needed. With a beverage it may be differentiating the product by the amount of carbonation, juice, or sweetener, thereby creating different product versions. This differentiation can take place close to the customer.

CULTURAL CHALLENGE

Culture is an important element of global supply chain management as it is a critical element of communication. Just consider differences in the amount of acceptable interpersonal distance between individuals of different cultures, or norms of formality in addressing someone. Some cultures tend to value promptness and single task focus, whereas other cultures do not. In Asia product packaging is much more important than in the West, as it is seen more of a reflection of the product itself. All these differences are attributable to culture and have a significant impact on managing global supply chains. However, culture is especially problematic as it can often be difficult to understand. This also includes differences in verbal communication and the use of humor, making direct translation of communication between cultures impossible. Further, specific cultural norms can be elusive and it can be difficult to determine just how pervasive they are.

Coca Cola's China Branding Challenge

Creating a brand image in a different culture with a different language and word meaning is an enormous challenge for companies competing in global markets. The brand needs to create a direct connection between the product and the market, and the linguistic nuances can affect the brand meaning. This, in turn, can affect consumer perceptions and brand identity.

Coca-Cola encountered this problem when trying to develop its brand name in China. When Coca-Cola first entered the Chinese market in 1928 they had no official representation of their name in Mandarin. The challenge was to find four Chinese characters whose pronunciations approximated the sound of the brand without producing a nonsensical or adverse meaning when strung together. This was a challenge. Initially shopkeepers created signs that combined characters whose pronunciations formed sounds similar to “coca-cola,” but they did so with no regard for the meanings of the written phrases they formed in doing so. In some cases this resulted in unflattering, nonsensical meanings such as “female horse fastened with wax,” “wax-flattened mare,” or “bite the wax tadpole” when read in Mandarin. The company then chose ![]() which meant “Can-Be-Tasty-Can-Be-Happy” opting for the character lè, meaning “joy.”

which meant “Can-Be-Tasty-Can-Be-Happy” opting for the character lè, meaning “joy.”

The story exemplifies linguistic nuances that can affect brand sound and brand meaning, when creating a brand image in global markets. Companies must realize prior to entry that each market is culturally distinct and that marketing requires some degree of localization.

Adapted from: Alon, I. (Ed.) Chinese Economic Transition and International Marketing Strategy. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 2003.

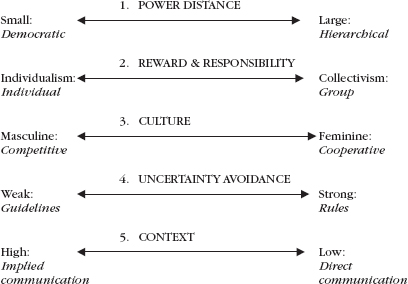

There are five important dimensions of culture that can help us understand how to conduct business in different parts of the globe.1 These dimensions explain differences in culture and help us understand how to do business in different parts of the globe, and are summarized in Figure 12.4. We look at the five dimensions of culture next.

FIGURE 12.4 Dimensional differences of culture.

- Small vs. Large Power Distance. Power distance is the extent to which there is a strong separation of individuals based on rank. Northern Europe and the United States have cultures with small power distance, where people relate to one another more as equals. This means that the organizational setting tends to be more democratic in nature. On the other hand some Latin American countries, Arab, and Asian countries tend to have a high power distance where relationships are formal and based on hierarchical positions. Understanding power distance has a significant impact on managing the workplace. Recall in the opener that traditionally in India power distance is large and that older workers have a difficult a time in a more democratic workplace that is more common in the West.

- Individualism vs. Collectivism. This dimension measures the extent to which people believe in individual responsibility and reward, rather than the reward of the group.

In individualist cultures, such as the United States, U.K., and the Netherlands, people are expected to be motivated by individual rewards. However, in collectivist cultures, such as Indonesia and West Africa, people are expected to be motivated by the benefits of the group as a whole. Understanding this dimension helps develop motivational structures for workers in different parts of the globe, as well as managing teams.

- Masculinity vs. Femininity. Masculine cultures are defined as those that value competitiveness, assertiveness, ambition, and the accumulation of wealth. By contrast, feminine cultures are those that value relationships, harmony, the environment, and quality of life. Japan is considered a more masculine culture, whereas the Netherlands a more feminine culture. The United States is close in the middle. Understanding these differences can be important in business negotiations and alliance building as parties from different cultures may value different aspects of the relationship.

- Weak vs. Strong Uncertainty Avoidance. This dimension refers to the degree of comfort members of a culture have with ambiguity and lack of structure. It measures the extent to which a culture prefers situations with clear rules over ambiguous situations. Cultures with strong uncertainty avoidance prefer explicit rules and are uncomfortable with ambiguity. Cultures with weak uncertainty avoidance prefer guidelines versus formal rules, and informal activities. These cultures are also more tolerant of risk, such as Japan and India. The U.K., United States, and Hong Kong tolerate less risk. This has important implications for job design, work structure, and innovation. Cultures that are more comfortable with ambiguity may be more innovative in thinking “outside of the box.” This dimension also has implications for employee retention rates. Employees in strong uncertainty avoidance cultures tend to stay longer with one employer, whereas in weak uncertainty avoidance employees change employers more frequently.

- High vs. Low Context Cultures. This last dimension of culture refers to the reliance on high context over low context messages when communicating. In high context cultures many things are left unsaid, letting the context explain the meaning. In low context cultures, “what you see is what you get.” Here the speaker is expected to precisely make their points with limited ambiguity. This is the case in the United States and Northern Europe. By contrast, in Japan facial expressions and what is not said provide clues to what is actually meant. In the United States and much of Europe, agreements are typically precise and contractual in nature; in Asia, there is a greater tendency to settle issues based on trust and understanding. Also, “saving face”—where no one openly losses or gets embarrassed—is of utmost importance.

These dimensions of culture explain key differences in behaviors and expectations. Their understanding is essential for successful global supply chain initiatives, which are based on communication. It is critical that managers understand these differences and keep them in mind as they conduct negotiations, collaborate, and build rapport with members of their supply chain across the globe.

GLOBAL INFRASTRUCTURE DESIGN

INFRASTRUCTURAL CHALLENGES

A successful global presence is dependent on having a physical supply network capable of responding to customer demands. The decisions that are involved in developing and managing the physical aspects of the network are referred to as infrastructure. This includes access to roads and transportation, organizational facilities, availability of skilled labor, systems for operations and distribution planning, quality of materials, and availability of suppliers. One of the biggest challenges for companies setting up global supply chains are the significant differences in infrastructure in developing countries. Companies often overlook the substantial deficiencies in infrastructural resources when they begin doing business in developing countries and often encounter significant challenges.

Labor. Access to low-cost labor has been a primary draw for companies setting up global operations. A good example of this has been seen when looking for engineering talent. The availability of low-cost, high-quality engineers in some developing countries has been a significant factor contributing to location decision of R&D facilities. Taiwan has been a primary location for firms looking for mechanical and electrical engineers, whereas India has been the primary source of software engineering talent. In contrast, the United States produces only 7% of engineers globally, driving many U.S. firms to locate their facilities off-shore, closer to a large supply of this low-cost, high-skill talent.

Having access to affordable and highly trained technical workers provides firms with significant capability. However, there are often many challenges in achieving successful performance. First, there are typically significant productivity differences between labor in other countries. This includes speed of work, precision, and quality, as well as acceptable work hours. Companies cannot simply translate labor productivity from one region to another. Second, there are often large variation in labor skills and capability. This can make it difficult to place comparable facilities in different parts of the globe. Lack of labor skills may require altering the production processes or the ability to use certain technologies. For example, there has been a growing use of numerically controlled machines in production processes in South American countries due to the difficulty in finding an adequate supply of trained machinists. The result has been an increased reliance on the technology as a substitute for skilled labor.

Transportation. Access to roadways and transportation can often be poor in developing countries. These weaknesses in transportation infrastructure can increase the length and variability of distribution lead times. Distribution channels in developing countries can be long and unpredictable. Often the product changes hands many times before reaching the final consumer using different modes of transportation. This may result in high variability in shipping times, uncertainty in delivery lead-time, and higher distribution costs. For example, in Russia the primary cause of food shortages is poor distribution. There is ample production but the difficulty is in distributing the food to all the locations needing it. For this reason when McDonald's went into Russia it organized its own distribution system with its own trucks.

Suppliers. Designing a global supply chain requires important decisions regarding the number of suppliers and their geographic locations. In general it is easier to manage fewer suppliers. However, this can create delivery risks due to high dependence on few suppliers. It also provides less flexibility if sudden excess capacity is needed. Finally, managing numerous and diverse suppliers across the globe can be a daunting task for companies.

Companies are often attracted to foreign suppliers due to substantially lower prices without considering factors such as quality and delivery. It is not uncommon to receive a lower bid without comparable quality from suppliers in developing countries. Lack of availability to high quality reliable suppliers can be a surprise. This can result in supply shortages and irregular schedules. These then create uncertainty throughout the supply chain and result in everyone keeping higher levels of inventory. In addition, global supply chains sometimes encounter material shortages of certain imported raw materials due to import restrictions. The result may be the unexpected need to redesign production processes in order to use less of the restricted material.

Companies have become very creative in developing approaches to overcome supply problems. For example, when McDonald's first went into Russia it faced significant problems as it did not have high-quality reliable Russian suppliers for its restaurant operations. The company finally realized that it would have to control almost all aspects of the supply chain to ensure the quality and reliability it needed. As a result they utilized a vertical integration strategy by developing their own plant and distribution facility for processing meat patties, producing French fries, preparing dairy products, baking buns and apple pies. They even grew their own potatoes to have product consistency.

ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY

Information technology is the tool that has broken down the barrier of distance between companies and geographic regions. Just consider the use of the Internet, bar codes, and RFID technology that enhance the speed and accuracy of information shared. Reliable and uninterrupted communication is essential for the functioning of a global firm. However, it is also something we often take for granted. Some geographic regions do not even have something as simple as reliable phone service. This means that information on supply and demand will not be readily available. This also means that collaboration between members of the supply chain will be difficult. Under these conditions a company will have to make a substantial investment in communication technology and must factor this cost into the location decision.

In addition to information technology there is manufacturing technology needed to provide flexibility to manufacturing processes necessary for mass customization. This enables companies to serve many markets. Recall that today's global markets are characterized by product diversity as customers want greater product customization. In addition, product life cycles are short, requiring ever-faster product introductions. Without innovative and flexible manufacturing technology companies would not be able to produce the large product varieties needed to compete in diverse global markets that change rapidly.

Another important technology is equipment technology used to transport and distribute products to different markets. These technologies have sped up the distribution process and made it much more reliable. These technologies coupled with information technology to enhance communication have enabled companies to produce large product varieties delivered efficiently to global markets.

COST CONSIDERATIONS

Companies are often attracted to global operations by lower labor costs, especially in underdeveloped or emerging nations. However, while local labor costs may be significantly lower, companies must consider overall costs of doing business globally. Often companies find overall operations costs to be significantly higher than expected. This may include higher transportation and distribution costs, cost to upgrade facilities and technology, as well as cost of space, tariffs, taxes, and other expenses related to doing business overseas. We look at these costs next.

HIDDEN COSTS

The strategy of going after lower labor costs in developing nations became especially popular with U.S. manufacturing firms in the l980s, in response to their own markets becoming flooded with low-priced imports. In order to compete, companies began to outsource the manufacture of goods to global sites with low cost labor. This strategy became especially popular in the assembly of electronic devices, such as computers and cell phones. It has also been popular in the retail industry in the manufacture of clothing.

Seeking low cost labor has made sense in situations where product life cycles are short, such as the frequent changes in models of cell phones. The alternative to cheap labor would require the building of an expensive assembly plant and the cost may not be justified for product models that change frequently. However, often the strategy of chasing low labor cost across the globe is a poor one for the following reasons. First, labor cost often constitutes a small percentage of overall cost. Second, locations of cheap labor change and shift over time, often after facilities have been put in place. This can leave companies with facilities and higher labor costs than originally planned. For example, Korea and Taiwan were cheap labor wage countries in the 1970s, Thailand in the early 1980s, then China in the 1990s. China continues to lead in low cost labor, but preference is increasingly moving into rural China and western China, away from the seaport. Third, companies often find that there are numerous hidden and unexpected costs in going global. Fourth, competitive priorities other than costs are increasingly becoming important and achieving success on those dimensions may not be optimal at locations with low skilled labor and poor infrastructure. Just being driven by labor cost can be misleading.

There may also be unexpected costs of additional training requirements due to lack of skilled workers. Companies are often surprised to find that workers in developing nations often lack rudimentary education. This can actually result in high costs due to poor quality of work, lower productivity, and a lack of quality culture among workers, increased lead-times and associated inventory costs due to poor transportation and communication infrastructure, and unexpected logistics complications due to multilevel and bureaucratic government structures.

Many firms have found that the hidden costs of outsourcing to developing nations can be hard to estimate. Nike learned this lesson in the 1980s with numerous start-up problems at a new production facility in China. In 1981, Nike began shoe production in China, but by 1984, production was well below expectations. The reasons were China's economic structure, a very uneducated labor force, and an unexpectedly poor transportation and communication infrastructure. Also often ignoring cultural incompatibilities between the firm's management and local workers can easily erode cost savings due to turnover and failure sin productivity and quality.

NON-COST CONSIDERATIONS

For many businesses the order-winners in their product markets have shifted beyond just cost toward other considerations, such as quality, delivery speed, product design, and customization. To compete on these dimensions companies need superior quality of labor, productivity, transportation, telecommunications, and a supplier infrastructure. These factors become more important in determining the location of facilities than merely labor cost.

The total quality management (TQM) movement is one development that has contributed to the awareness of non-cost considerations. TQM brought about a focus on the total cost of quality, rather than just direct labor cost, and had shifted from inspection to prevention. Companies began to understand that activities conducted prior to production, such as product design and worker training significantly impacted overall costs. The costs of poor design, poor material quality, defects, scrap, and poor workmanship were all measurable and added to total cost. These realizations placed access to skilled workers and quality suppliers high on the priority list for firms competing on quality. Lack of worker skills, inadequate transportation and communication infrastructure, and low-quality supply are ultimately extremely costly for the implementation of a global supply chain.

MANAGERIAL INSIGHTS BOX—BEYOND COST

BMW

There are many benefits to maintaining geographic proximity to customers, particularly in markets where customers demand high customization and fast delivery. For this reason BMW chose to locate its state-of-the-art plant in Leipzig, Germany, right in the center of its market. The company chose to equip the facility, which opened in 2005, with numerous innovations to give BMW the ability to customize cars very late in the production process. Rather than cost, BMW's customers want quick delivery and the possibility of changing their orders after they have placed them. What they usually want is to add more optional equipment—a very high margins and lucrative business for BMW. In order to accommodate its customers, the Leipzig plant is designed to both reduce delivery lead time and increase the possibility of modifying the order after the car is actually put into production. This enables BMW to be responsive to the latest changes in the market and compete on flexibility.

The flexibility of BMW's factories allows for huge variations on basic models that would be virtually impossible for any other automaker. At the Leipzig plant seemingly random parts—ranging from dashboards and seats to axles—snake onto overhead conveyer belts to be lowered into the assembly line in precise sequence according to customers' orders. BMW buyers can select everything from engine type to the color of the gear-shift box to a seemingly limitless number of interior trims. They can then change their mind and order a completely different configuration in as little as five days before production begins. Customers have loved the flexibility with roughly 170,000 changes being placed per month. There are so many variations that line workers assemble exactly the same car only about once every nine months.

That level of individualization would be impossible to achieve at most automakers due to the complexity and cost. However, BMW has emerged as a sort of anti-Toyota. While Toyota excels in simplifying, BMW excels in mastering complexity and tailoring cars to customers' tastes. That's what differentiates BMW from Lexus and the rest of the premium pack. “BMW drivers never change to other brands,” says Yoichi Tomihara, president of Toyota Deutschland, who concedes that Toyota lags behind BMW in the sort of customization that creates emotional appeal.

In addition to cutting edge technology and facilities, this level of innovation comes from a highly inclusive culture. Ideas flow from the bottom up, which helps keep BMW's new models fresh and edgy year after year. Young designers in various company studios, from Munich headquarters to Design Works in Los Angeles, are constantly pitted against one another in heated competitions. Unlike many car companies, where a design chief dictates a car's outlines to his staff, BMW designers are given only a rough goal but are otherwise free to come up with their best concepts.

Inclusion in design and production extends to suppliers. The facility has a large building for its major suppliers to set up shop within walking distance of the assembly line. This proximity allows the suppliers to react quickly to changes in the production schedule. A sophisticated IT system connects the factory to its suppliers, distribution channels, and BMW sales offices and dealers to keep everyone abreast of the latest changes. The goal is to reduce the lead time for customers in Germany to 10 days and allow them to modify their orders even within that period. For this reason many have dubbed BMW's plant as the “dream factory.”

Adapted from: “BMW's Dream Factory.” Bloomberg Businessweek, October 16, 2006.

POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC FACTORS

Decisions to develop and manage a global supply chain network must consider the global political and economic environment. This environment is increasingly complex and turbulent, and must be evaluated on a continual basis. Political instability and hostility toward foreign businesses is a serious consideration. Currency rate fluctuations can help or hurt global operations and require careful analysis. Regional trade agreements, such as NAFTA, and trade protection mechanisms, such as tariffs and trigger price mechanisms also influence the decision to globalize operations. These factors can either significantly ease global operations or create large barriers, and must be carefully considered. Let's look at some of these in a bit more detail.

IMPACT OF EXCHANGE RATE FLUCTUATIONS

Imagine you are visiting Europe and want to purchase a cup of coffee priced at 3.00 euros at the coffee shop. That doesn't seem unreasonable until you suddenly find that you have to pay 4.20 in U.S. dollars for that coffee as the exchange rate is 1.40. Suddenly you may find the coffee is much more expensive than you thought. This is the same problem supply chain managers encounter with fluctuating currency exchange rates. They can find themselves in a financial situation where their purchasing power is diminished literally overnight.

The exchange rate between two currencies specifies how much one currency is worth in terms of the other. For example, the exchange rate between the European euro and the United States dollar has fluctuated over the past 10 years from one euro being equal to 0.825 dollars (in October 2000) to 1.285 (in February 2004) to 1.40 (in November 2010). This means that you would need 1.40 dollars to equal one euro. Similarly, the value of the Japanese yen has fluctuated in the range 80 to 140 yen per dollar. These fluctuations occur on a continual basis and can last for months or years. Small fluctuations are expected and do not have a large impact. However, large fluctuations can have huge implications for global operations. It means that the ability to purchase in the currency you possess is suddenly diminished with no fault of your own. Supply chain managers have to include these fluctuations in their management strategies and there are certain strategies they can use to help minimize their exposure to these risks.

One strategy to minimize risks of exchange rate fluctuations is to maximize operational flexibility. This can be accomplished by diversifying production geographically using global sourcing networks. By diversifying geographically a company can shift more of its production to facilities and suppliers that are located in a lower cost area when local currencies shift. For example, if the local currency tends to be consistently undervalued—such as in some Eastern European countries—it is better to shift most sourcing to local vendors. However, the firm may still want to source a limited amount of its inputs from less favorable suppliers in other countries if it feels that maintaining an ongoing relationship may help in the future when strategies need to be reversed.

REGIONAL TRADE AGREEMENTS

Trade agreements are pacts between countries that encourage trade in a region by eliminating or lowering tariffs, quotas, and other trade barriers. The purpose is to protect trade in the region, and increase regional growth, by giving preference to members of the pact. Many trading blocks have emerged globally, such as in Europe (Europe l992) and North America (NAFTA). There are also numerous trade agreements between countries in Asia and the Pacific Rim, such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC). APEC has 18 member countries, including the United States, China, and Japan, with the goal of free and open trade in the region by 2020. This has serious implications for the way firms structure their global supply chain network as they have to be aware of the opportunities, as well as restrictions, such trade agreements provide.

Creation of NAFTA resulted in the elimination of nearly 7,000 individual tariffs, duties, and nontariff barriers to trade. For example, NAFTA changed the role of maquiladoras for American companies. Maquiladoras refers to an operation that involves manufacturing in a foreign country and importing materials and equipment on a tariff-free basis for assembly or manufacturing, then exporting the assembled or manufactured product, often back to the original country. American owned maquiladoras enabled cheap labor on production, which incurred tariffs only on the low-cost labor portion of the product. NAFTA eliminated the tariff barriers, which changed the role of maquiladoras. NAFTA also resulted in the rise of Mexico's national content requirement from 36% to 62.5%. This resulted in European and Japanese firms now wanting to invest in North American production in order to qualify for the preferential tariff treatment.

IMPACT OF NON-TARIFF BARRIERS

Most of us have heard of tariffs—taxes and duties on imported goods—as a barrier to global trade. However, tariffs have become a less significant form of trade protection due to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and more recently the World Trade Organization (WTO), which have dramatically reduced the tariffs for most industrial goods traded among developed countries. GATT and WTO have resulted in a rise of global trade. However, it is the non-tariff barriers—various forms of indirect, non-price trade protection— that have become far more significant as obstacles to global exports and imports. Let's look at some of the most important non-tariff barriers.

Import quotas—a quantitative restriction on the volume of imports—is one of the most common forms of non-tariff barriers. An example of this is the use of textile quotas that are imposed by industrialized countries against textile imports from developing countries in order to keep a viable domestic industry. Another non-tariff barrier is a trigger price mechanism, which is the establishment of minimum price for sales by an exporter from a foreign country. Yet another form is the setting of “local content requirements,” which specify that a certain portion of the value added must be produced inside the country. For example, the European Union has established strict local content rules. This has driven both Texas Instruments and Intel to built semiconductor facilities in Europe to respond to the increase in the amount of semiconductor processing required by the new local content rules.

Other barriers include the use of technical standards and health regulations, which relate to matters such as consumer safety, health, the environment, labeling, packaging and quality standards. For example, for many years Japan refused to import U.S. skis on the grounds that Japanese snow was different from U.S. snow. Similarly, the United States prohibits imports of many types of agricultural products on such grounds.

Countries come with many non-tariff barriers to protect domestic businesses. Despite these efforts, global trade is flourishing. There is an increase in harmonization of regulation and standards across the globe, making managing global supply chains easier.

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

- Globalization growth is a result of advances in transportation and information technology, and a rise in personal income.

- Six forces that impact global supply chains are market and competition, cost, infrastructure, technology, political and economic environment, and culture.

- Global marketing is an approach that focuses on bringing standardization to the global market. Local marketing stresses micro-segmentation and localized differentiation. These approaches are contradictory, but they are best used to complement one another when developing a global strategy.

- The availability of infrastructure in global supply chains is a significant factor for going global. Infrastructure includes transportation, access to labor, warehousing, and access to suppliers.

- Technology is a significant factor in enabling the functioning of global supply chains. Three types of technology are important: information technology, manufacturing technology, and equipment technology.

- A significant factor in global supply chains is cost. Pursuing apparent cost reductions can be problematic as there are numerous hidden costs. Also, companies must take into account many non-cost considerations, such as quality and proximity to customers.

- Global supply chain management is impacted by political and economic factors, such as politics and government regulations, tariffs and various non-tariff barriers that include import quotas, trigger price mechanisms, and labor content regulation.

KEY TERMS

- Economic

- Cultural

- Political

- Demographic

- Market and competition

- Cost

- Infrastructure

- Technology

- Politics and economy

- Culture

- Global marketing

- Local marketing

- Product postponement

- Information technology

- Manufacturing technology

- Equipment technology

- Regional trade agreements

- Trade protection mechanisms

- Import quotas

- Trigger price mechanism

- Local content requirements

- Technical standards and health regulations

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Think of a product you are familiar with—the clothes you are wearing or the beverage you just drank or the book you are reading. Identify the challenges that would be involved in distributing this product on a global scale to different markets.

- Come up with a new product idea. How might you modify this product to sell it to different global markets? How would you market this product globally?

- You have US$1,500 to spend on a trip abroad. Explain the impact of currency fluctuations on your trip and what you can purchase if you choose to go to Asia versus Australia versus Europe versus Africa.

- Think of an idea you are passionate about. How would you sell your idea to a high content versus low content culture? How about a low power distance versus high power distance culture?

CASE STUDY: Wú's BREW WORKS

One hot afternoon, Kenneth Wú sat on the narrow steps of his apartment complex in Hong Kong, enjoying his latest creation: an alcoholic beverage he made from his own kitchen. The drink tasted so good that he preferred to drink it instead of store-bought beer. When Wú paid a visit to friends in Tai-Koo Sing, they ridiculed him for making his own alcohol, but eventually they tried it out of sheer curiosity. To Wú's surprise, his friends unanimously agreed that his beverage would be worth paying money for. That evening, they developed an entrepreneurial spirit, and by the end of the night, Wú was convinced that his concoction could generate a substantial amount of revenue. Later that week, despite Wú's aversion to taking the risks required of an entrepreneur, he decided to manufacture and sell his beverage.

Wú and his friends began by going to different liquor stores in the Hong Kong region to offer samples. The liquor store owners fell in love with his beverage and soon Wú had his own drink on shelves around the region. He named the drink “Wú's Brew.” After a year of steady sales and considerable profit, Wú decided to expand his sales to other countries in East Asia. Based on the advice and esteem he had received from many of these small liquor storeowners, he decided to start a partnership with a few of his close friends in order to sell the product and market what they believed to be the “next big thing” to hit the bars and shelves around the world. His company was named Wú's Brew Works.

Wú wisely acknowledges that he and his friends will never be able to meet global demand if they continue to manufacture the product from their homes. By relying on the relationships he developed with storeowners and their networks Wú expands his manufacturing operations. Sure enough, Wú's drink becomes the most popular item to hit the market in Hong Kong and countries such as Taiwan and the Philippines. Within a year, the beverage begins receiving global attention throughout East Asia. People and tourists from China, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, and other East Asian countries start requesting his beverage when visiting Hong Kong. Eventually, people throughout the world—including Australia, Europe, and even the United States—become interested.

Wú begins to envision his product being sold globally. After securing financial commitments from various Hong Kong investors, Wú and his partners rent out the 65th floor of Central Plaza in Wanchai North of the Hong Kong Island region of Hong Kong to locate company operations and the official Wú's Brew Works headquarters. However, he chooses to locate the manufacturing plant in Yenda, Australia as it provides more convenient distribution access.

Wú'S BREW WORKS MANUFACTURING PLANT

Yenda, Australia is a little town located about 560 km west of Sydney in the New South Wales region of Australia. It is the location where Yellow Tail wine is manufactured and produced. Yenda is a multicultural place where vineyards and rice paddies thrive. It is located at the edge of Cocoparra National Park—a place of spectacular gorges, waterfalls, walking locations in lookouts, and home to more than one hundred species of birds. Wú and Co. decide to have the manufacturing plant in Yenda because of its open land and large capacity for a plant.

Wú decides to target the United States in its business plan to begin global growth; the United States will be the first area outside of East Asia to sell Wú's Brew. Wú sought the U.S. market to fulfill his ambition of spreading his product globally because of the large growth potential for alcohol in the United States. However, alcohol is a highly regulated product in the United States and all alcoholic imports coming into the United States have to follow a three-tier system of alcohol distribution.

THE THREE-TIER SYSTEM

The three-tier system is the system for distributing alcoholic beverages in the United States that was federally mandated after the repeal of the Prohibition in 1933. The three tiers in this system are the producers, distributors, and the retailers. In this system, the delivery of an alcoholic beverage involves the producer to sell to a distributor, who then must sell the product to a retailer, whether it is a liquor store, restaurant or bar. This system is designed to help ensure the responsible and safe distribution of alcoholic beverages, and is a key factor in preventing the distribution of alcohol to minors. It provides a process that guarantees the integrity of products to end consumers.

Different states have various rules and exceptions. In some states, under the brewpub system, a producer (brewers, distillers, wineries, and imports of alcohol) can sell its alcohol directly to retailers and has no obligation to include a distributor in its supply chain. Other states allow a two-tier system, which allows breweries to act as their own distributor so that they can distribute alcohol directly to retailers. In some states such as Oregon, intrastate shipments of alcohol directly from the producers to retailers or customers are permitted. Most of the states, however, including Texas and California, adhere to the three-tier system of alcohol distribution.

PROJECT PROPOSAL PLAN

After becoming fully educated about the risks and regulations of alcohol distribution in the United States, Wú and his company decide that expanding into the United States would be a good growth opportunity. Wú's Brew Works' corporate managers come up with three different project proposals to distribute alcohol to the United States. Each of the three project proposals are plans to market the product to one particular region of the United States and partner with one distributor because Wú's Brew Works and other international importers of alcohol are not allowed to distribute the product while remaining in the country. They are only allowed to sell the product to the distributor (usually located on the West Coast). Their plan is to select only one of the project proposals because of capital constraints. Ultimately, they can afford only to work with one distributor that brings the product to just one region of the United States.

The distributor that Wú's Brew Works chooses would not only sell within their respective area, but would also consolidate Wú's product with other international alcohol products to sell to retailers from inland states. This arrangement allows inland retailers to get around their legal inability to buy alcohol directly from the alcohol producer. Wú's West Coast distributors are therefore also known as distribution consolidators. These consolidators would be able to bring Wú's Brew to distributors in Texas or Kansas.

The first project proposal was a plan to partner with R.F. Michinan, located in the ports of Los Angeles, California. The project would require bringing the product to the Port of Los Angeles and ultimately marketing it to the southern United States, such as Texas and Louisiana. The second project proposal was with JH Distributors and would allow Wú's Brew to be brought to the northwest region and most of the midwest regions of the United States. JH Distributors is located in Lake Oswego, Oregon, so the product would have to be brought to the port of Portland, Oregon. The final project proposal was to market the product in the east and northeast regions of the United States by partnering with SJT Distributors, located in San Francisco, California, and accessed through the ports of San Francisco. No project is considerably more profitable than the other.

Each project has its own risks. For the first project proposal, R.F. Michinan said that the risks of distributing alcohol are minimal and that Wú had nothing to worry about. However, based on reports from the city of Los Angeles, there have been many cases of theft of alcohol imports from R.F. Michinan. For the second project proposal, JH Distributors stated the risk of longer lead times and exposure to lost or damaged products due to long transport from Australia to the port of Portland. Delivering from overseas to the port required going through the Columbia River and navigating in Oregon. The last project proposal with SJT Distributors had risk of longer lead times to get the product from California across the United States to the eastern side of the United States. This could also make emergency production processes even more complicated.

In order for the plan to be implemented, Wú's Brew would have to be shipped on truck from its manufacturing plant in Yenda, Australia to the Sydney Harbor in Sydney, Australia. The product would then be loaded onto a ship, which would bring the product to the port of Los Angeles, the port of Portland, or the port of San Francisco, depending on which project Wú chooses. The international transport is DDP, which stands for “delivered duty paid.” This is a code that represents the way international shipments are organized. DDP requires the seller (Wú) to bear all costs and risks of bringing the alcohol to the United States. But once Wú's Brew is brought to the port of its destination, the distributor is responsible for the rest.

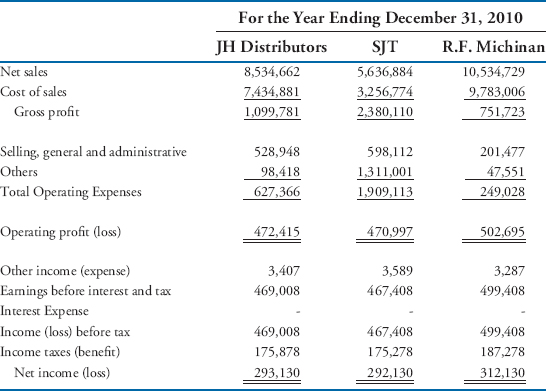

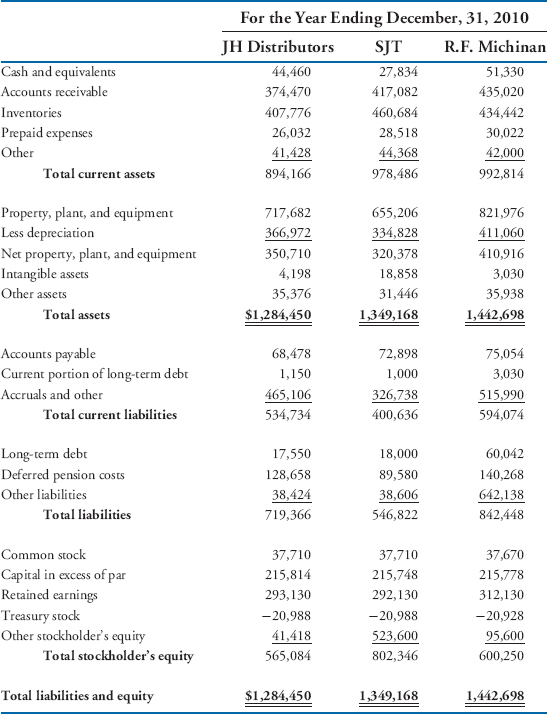

The statement of operations and balance sheet of the three companies are displayed in Exhibits 1 and 2, respectively. The projected cash flows of all three projects are displayed in Exhibit 3.

EXHIBIT 1 Consolidated Statement of Operations

EXHIBIT 2 Consolidated Balance Sheet (dollars in thousands)

EXHIBIT 3 Projected Cash Flows for 3 Projects2

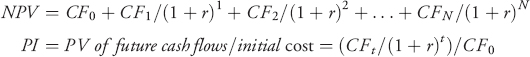

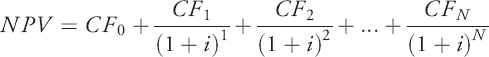

Profitability Index (PI) shows the relative profitability of any project. (PV per dollar of initial cost) A project is acceptable if its PI is greater than 1.0

JH DISTRIBUTORS

JH Distributors is a major distributor and consolidator of alcohol located in Lake Oswego, Oregon. They distribute alcohol throughout the northwest region and parts of the midwest regions in the United States. Although they are headquartered in Lake Oswego, a city south of Portland, Oregon, their major warehouse is located in Portland near the port of Portland. They also have several distribution centers located in various parts of Oregon and states that surround Oregon. The owner of this privately held company, Julie Stables, is a long-time friend of Wú's.

After talking and negotiating with each of the companies he is trying to partner with, Wú is convinced that choosing project 2 with JH Distributors would be best for Wú's Brew. This is because of the high net present value this project has over the other two and also because of the trust that he has developed with Julie, his contact at JH Distributors. This personal relationship would help solidify the collaboration between the two companies. Wú's Brew Works and JH Distributors decide to begin the partnership.

THE CHALLENGE

Within two months of agreement between the two companies, Wú's Brew Works reviewed its purchase order from JH Distributors and produced the 2,100 cases ordered. Wú's Brew Works hired a third-party logistics (3PL) provider to deliver the product in full-truck load from Yenda to Sydney, Australia and then on a ship from Port Jackson in Sydney to the mouth of the Columbia River. From the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon, the ship sailed to Portland where it went through customs and other legal screens. Because the international transport was “delivered duty paid,” JH Distributors did not have to worry about any of the costs prior to receiving the shipment from the port.

However, when receiving the shipment, JH Distributors claimed that they had only received 1,849 cases of the alcohol. When this was reported to their headquarters in Lake Oswego, Julie thought to herself, “That's strange, we ordered 2,700 cases. How did it get down to 1,849?” Some of the crewmembers aboard the ship claimed that they saw a lot of the alcohol bottles broken from the cases and so they threw what was unusable overboard from the ship. There were some violent storms in the Northern Pacific Ocean that might have caused this. This also caused the shipment to be late by two days. Later, while JH Distributors transported full truck loads of alcohol up north on I-5, they encountered a police chase from a local bank robbery, which delayed the shipment even further. The robbers from California were caught, but had crashed into one of the truckloads of the alcohol delivery JH Distributors was distributing from the port to its main warehouse.

By the time the shipment had arrived to the warehouse, they realized that there were only 1,507 cases that arrived. When JH Distributors questioned Wú's Brew Works regarding the problem, Wú's Brew Works claimed they had done everything properly. When asked about only producing 2,100 cases, Wú's Brew Works claimed that the purchase order indicated exactly 2,100 cases and not 2,700. After reexamining the PO (purchase order), JH Distributors had realized that the 2,700 on the PO looked like 2,100 and so it was incorrectly inputted in its systems.

After all the troubling events, Wú and Julie wondered if their companies could recover. Although Wú believes that project 2 with JH Distributors is still the project that Wú's Brew Works should pursue, some of his corporate managers beg to differ.

CASE QUESTIONS

- Based on all the setbacks in the alcohol supply chain, whose fault is it for all the events leading to the 1,200 case shortage of Wú's Brew?

- Was bringing Wú's Brew into the United States a good idea in the first place given the heavy regulation? Why?

- Disregarding Wú's Brew first decision to invest in project 2 with JH Distributors, which project should it have invested in based only on the financial information provided? (Use NPV as noted in the case)

- Kenneth Wú had chosen JH Distributors to partner with in hopes of bringing a very popular product to the United States. Based on all the risks mentioned in the case article, would you have done the same?

- All the events have left an a bad impression on some of Wú's Brew Works managers Should Wú's Brew Works continue project 2 with JH Distributors? If not, then which project?

REFERENCES

Ailon, G. “Mirror, mirror on the wall: Culture's consequences in a value test of its own design.” Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 2008: 885–904.

Harrison, Terry P., Hau L. Lee and John J. Neale. The Practice of Supply Chain Management. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishing, 2003.

Hofstede, Geert. Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2001.

Hofstede, Geert. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 2nd Edition. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Lee, Hau L., and Chung-Yee Lee. Building Supply Chain Excellence in Emerging Economies. New York, NY: Springer Science, 2007.

Samovar, Larry A., and Richard E. Porter. Communication Between Cultures, 5th Edition. Stamford, Conn: Thompson and Wadsworth, 2004.