With high expectations, Euro Disney opened just outside Paris in April 1992. Success seemed assured. After all, the Disneylands in Florida, California, and, more recently, Japan were all spectacular successes. But somehow all the rosy expectations became a delusion. The opening results cast even the future continuance of Euro Disney into doubt. How could what seemed so right have been so wrong? What mistakes were made?

Perhaps a few early omens should have raised some cautions. Between 1987 and 1991, three $150 million amusement parks had opened in France with great fanfare. All had fallen flat, and by 1991 two were in bankruptcy. Now Walt Disney Company was finalizing its plans to open Europe's first Disneyland early in 1992. This would turn out to be a $4.4 billion enterprise sprawling over 5,000 acres 20 miles east of Paris. Initially it would have six hotels and 5,200 rooms, more rooms than the entire city of Cannes, and lodgings were expected to triple in a few years as Disney opened a second theme park to keep visitors at the resort longer.

Disney also expected to develop a growing office complex, this to be only slightly smaller than France's biggest, La Defense, in Paris. Plans also called for shopping malls, apartments, golf courses, and vacation homes. Euro Disney would tightly control all this ancillary development, designing and building nearly everything itself, and eventually selling off the commercial properties at a huge profit.

Disney executives had no qualms about the huge enterprise, which would cover an area one-fifth the size of Paris itself. They were more worried that the park might not be big enough to handle the crowds:

"My biggest fear is that we will be too successful."

"I don't think it can miss. They are masters of marketing. When the place opens it will be perfect. And they know how to make people smile—even the French."[123]

Company executives initially predicted that 11 million Europeans would visit the extravaganza in the first year alone. After all, Europeans accounted for 2.7 million visits to the U.S. Disney parks and spent $1.6 billion on Disney merchandise. Surely a park in closer proximity would draw many thousands more. As Disney executives thought about it, the forecast of 11 million seemed too conservative. They reasoned that because Disney parks in the United States (population 250 million) attracted 41 million visitors a year, then if Euro Disney attracted visitors in the same proportion, attendance could reach 60 million with Western Europe's 370 million people. Table 9.1 shows the 1990 attendance at the two U.S. Disney parks and the newest Japanese Disneyland, as well as the attendance/population ratios.

Adding fuel to the optimism was the fact that Europeans typically have more vacation time than U.S. workers. For example, five-week vacations are commonplace for French and Germans, compared with two to three weeks for Americans.

The failure of the three earlier French parks was seen as irrelevant. Robert Fitz-patrick, Euro Disneyland's chairman, stated, "We are spending 22 billion French francs before we open the door, while the other places spent 700 million. This means we can pay infinitely more attention to details—to costumes, hotels, shops, trash baskets—to create a fantastic place. There's just too great a response to Disney for us to fail."[124]

Table 9.1. Attendance and Attendance/Population Ratios, Disney Parks, 1990

Visitors | Population | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

(millions) | |||

Source: Euro Disney, Amusement Business Magazine. | |||

Commentary: Even if the attendance/population ratio for Euro Disney is only 10 percent, which is far below that of some other theme parks, still 31 million visitors could be expected. Euro Disney "conservatively" predicted 11 million the first year. | |||

United States | |||

Disneyland (Southern California) | 12.9 | 250 | 5.2% |

Disney World/Epcot Center (Florida) | 28.5 | 250 | 11.4% |

Total United States | 41.4 | 16.6% | |

Japan | |||

Tokyo Disneyland | 16.0 | 124 | 13.5% |

Euro Disney | ? | 310[a] | ? |

[a] Within a two-hour flight. | |||

Nonetheless, a few scattered signs indicated that not everyone was happy with the coming of Disney. Leftist demonstrators at Euro Disney's stock offering greeted company executives with eggs, ketchup, and "Mickey Go Home" signs. Some French intellectuals decried the pollution of the country's cultural ambiance with the coming of Mickey Mouse and company: They called the park an American cultural abomination. The mainstream press also seemed contrary, describing every Disney setback "with glee." And French officials negotiating with Disney sought less American and more European culture at France's Magic Kingdom. Still, such protests and bad press seemed contrived and unrepresentative, and certainly not predictive. Company officials dismissed the early criticism as "the ravings of an insignificant elite."[125]

In the search for a site for Euro Disney, Disney executives examined 200 locations in Europe. The other finalist was Barcelona, Spain. Its major attraction was warmer weather. But the transportation system was not as good as around Paris, and it also lacked level tracts of land of sufficient size. The clincher for the decision for Paris was its more central location. Table 9.2 shows the number of people within two to six hours of the Paris site.

The beet fields of the Marne-la-Vallee area were the choice. Being near Paris seemed a major advantage, because Paris was Europe's biggest tourist draw. And France was eager to win the project to help lower its jobless rate and also to enhance its role as the center of tourist activity in Europe. The French government expected the project to create at least 30,000 jobs and to contribute $1 billion a year from foreign visitors.

Table 9.2. Number of People within 2–6 Hours of the Paris Site

Source: Euro Disney, Amusement Business Magazine. | |

|---|---|

Commentary: The much more densely populated and geographically compact European continent makes access to Euro Disney far more convenient than in the United States. | |

Within a 2-hour drive | 17 million people |

Within a 4-hour drive | 41 million people |

Within a 6-hour drive | 109 million people |

Within a 2-hour flight | 310 million people |

To encourage the project, the French government allowed Disney to buy up huge tracts of land at 1971 prices. It provided $750 million in loans at below-market rates, and also spent hundreds of millions of dollars on subway and other capital improvements for the park. For example, Paris's express subway was extended out to the park; a 35-minute ride from downtown cost about $2.50. A new railroad station for the high-speed Train a Grande Vitesse was built only 150 yards from the entrance gate. This enabled visitors from Brussels to arrive in only 90 minutes. And when the English Channel tunnel opened in 1994, even London was only 3 hours and 10 minutes away. Actually, Euro Disney was the second-largest construction project in Europe, second only to construction of the Channel tunnel.

Euro Disney cost $4.4 billion. Table 9.3 shows the sources of financing in percentages. The Disney Company had a 49 percent stake in the project, which was the most that the French government would allow. For this stake, it invested $160 million, while other investors contributed $1.2 billion in equity. The rest was financed by loans from the government, banks, and special partnerships formed to buy properties and lease them back.

The payoff for Disney began after the park opened. The company received 10 percent of Euro Disney's admission fees and 5 percent of the food and merchandise revenues. This was the same arrangement Disney had with the Japanese park. But in the Tokyo Disneyland, the company took no ownership interest, opting instead only for the licensing fees and a percentage of the revenues. The reason for the conservative position with Tokyo Disneyland was that Disney money was heavily committed to building Epcot Center in Florida. Furthermore, Disney had some concerns about the Tokyo enterprise. This was the first non-American Disneyland and also the first cold-weather one. It seemed prudent to minimize the risks. But this turned out to be a significant blunder of conservatism, for Tokyo became a huge success, as the following Information Box discusses in more detail.

Table 9.3. Sources of Financing for Euro Disney (percent)

Total to Finance: $4.4 billion | 100% |

|---|---|

Source: Euro Disney. | |

Commentary: The full flavor of the leverage is shown here, with equity comprising only 32 percent of the total expenditure. | |

Shareholders' equity, including $160 million from Walt Disney Company | 32 |

Loan from French government | 22 |

Loan from group of 45 banks | 21 |

Bank loans to Disney hotels | 16 |

Real estate partnerships | 9 |

With the experiences of the previous theme parks, and particularly that of the first cold-weather park in Tokyo, Disney construction executives were able to bring state-of-the-art refinements to Euro Disney. Exacting demands were placed on French construction companies, and a higher level of performance and compliance resulted than many thought possible to achieve. The result was a major project on time if not completely on budget. In contrast, the Channel tunnel was plagued by delays and severe cost overruns.

One of the things learned from the cold-weather project in Japan was that more needed to be done to protect visitors from wind, rain, and cold. Consequently, Euro Disney's ticket booths were protected from the elements, as were the lines waiting for attractions, and even the moving sidewalk from the 12,000-car parking area.

Certain French accents—and British, German, and Italian accents as well—were added to the American flavor. The park had two official languages, English and French, but multilingual guides were available for Dutch, Spanish, German, and Italian visitors.

Discoveryland, based on the science fiction of France's Jules Verne, was a new attraction. A theater with a full 360-degree screen acquainted visitors with the sweep of European history. And, not the least modification for cultural diversity, Snow White spoke German, and the Belle Notte Pizzeria and Pasticceria were right next to Pinocchio.

Disney foresaw that it might encounter some cultural problems. This was one of the reasons for choosing Robert Fitzpatrick as Euro Disney's president. While American, he spoke French and had a French wife. However, he was not able to establish the rapport needed, and was replaced in 1993 by a French native. Still, some of his admonitions that France should not be approached as if it were Florida fell on deaf ears.

As the April 1992 opening approached, the company launched a massive communications blitz aimed at publicizing the fact that the fabled Disney experience was now accessible to all Europeans. Some 2,500 people from various print and broadcast media were lavishly entertained while being introduced to the new facilities. Most media people were positively impressed with the inauguration and with the enthusiastic spirit of the staffers. These public relations efforts, however, were criticized by some for being heavy-handed and for not providing access to Disney executives.

As 1992 wound down after the opening, it became clear that revenue projections were, unbelievably, not being met. But the opening turned out to be in the middle of a severe recession in Europe. European visitors, perhaps as a consequence, were far more frugal than their American counterparts. Many packed their own lunches and shunned the Disney hotels. For example, a visitor named Corine from southern France typified the "no spend" attitude of many: "It's a bottomless pit," she said as she, her husband, and their three children toured Euro Disney on a three-day visit. "Every time we turn around, one of the kids wants to buy something."[127] Perhaps investor expectations, despite the logic and rationale, were simply unrealistic.

Indeed, Disney had initially priced the park and the hotels to meet revenue targets, and assumed that demand was there at any price. Park admission was $42.25 for adults—higher than at the American parks. A room at the flagship Disneyland Hotel at the park's entrance cost about $340 a night, the equivalent of a top hotel in Paris. It was soon averaging only a 50 percent occupancy. Guests were not staying as long or spending as much on the fairly high-priced food and merchandise. We can label the initial pricing strategy at Euro Disney as skimming pricing. The following Information Box discusses skimming and its opposite, penetration pricing.

Disney executives soon realized they had made a major miscalculation. While visitors to Florida's Disney World often stayed more than four days, Euro Disney— with one theme park compared to Florida's three—was proving to be a two-day experience at best. Many visitors arrived early in the morning, rushed to the park, staying late at night, then checked out of the hotel the next morning before heading back to the park for one final exploration.

The problems of Euro Disney were not public acceptance (despite the earlier critics). Europeans loved the place. Since the opening it had been attracting just under 1 million visitors a month, thus easily achieving the original projections. Such patronage made it Europe's biggest-paid tourist attraction. But large numbers of frugal patrons did not come close to enabling Disney to meet revenue and profit projections and cover a bloated overhead.

Other operational errors and miscalculations, most of them cultural, hurt the enterprise. The policy of serving no alcohol in the park caused consternation in a country where wine is customary for lunch and dinner. (This policy was soon reversed.) Disney thought Monday would be a light day and Friday a heavy one, and allocated staff accordingly, but the reverse was true. It found great peaks and valleys in attendance: The number of visitors per day in the high season could be ten times the number in slack times. The need to lay off employees during quiet periods came up against France's inflexible labor schedules.

One unpleasant surprise concerned breakfast. "We were told that Europeans don't take breakfast, so we downsized the restaurants," recalled one executive. "And guess what? Everybody showed up for breakfast. We were trying to serve 2,500 breakfasts at 350-seat restaurants. The lines were horrendous."[128]

Disney failed to anticipate another demand, this time from tour bus drivers. Restrooms were built for 50 drivers, but on peak days 2,000 drivers were seeking the facilities. "From impatient drivers to grumbling bankers, Disney stepped on toe after European toe."[129]

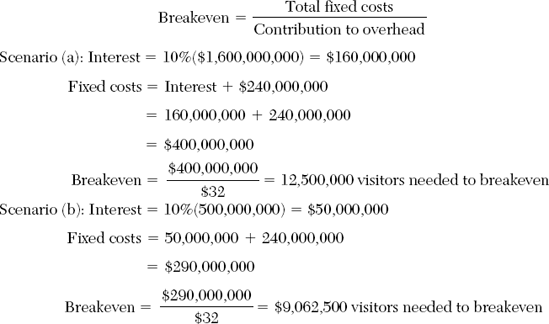

For the fiscal year ending September 30, 1993, the amusement park had lost $960 million, and the future of the park was in doubt. (As of December 31, 1993, the cumulative loss was 6.04 billion francs, or $1.03 billion.) The Walt Disney corporation made $175 million available to tide Euro Disney over until the next spring. Adding to the problems of the struggling park were heavy interest costs. As depicted in Table 9.3, against a total cost of $4.4 billion, only 32 percent of the project was financed by equity investment. Some $2.9 billion was borrowed primarily from 60 creditor banks, at interest rates running as high as 11 percent. Thus, the enterprise began heavily leveraged, and the hefty interest charges greatly increased the overhead to be covered from operations. Serious negotiations began with the banks to restructure and refinance.

The $960 million lost in the first fiscal year represented a shortfall of more than $2.5 million a day. The situation was not quite as dire as these statistics would seem to indicate. Actually, the park was generating an operating profit. But nonoperating costs were bringing it deeply into the red.

While operations were far from satisfactory, they were becoming better. It had taken 20 months to smooth out the wrinkles and adjust to the miscalculations about hotel demand and the willingness of Europeans to pay substantial prices for lodging, meals, and merchandise. Operational efficiencies were slowly improving.

By the beginning of 1994, Euro Disney had been made more affordable. Prices of some hotel rooms were cut—for example, at the low end, from $76 per night to $51. Expensive jewelry was replaced by $10 T-shirts and $5 crayon sets. Luxury sit-down restaurants were converted to self-service. Off-season admission prices were reduced from $38 to $30. And operating costs were reduced 7 percent by streamlining operations and eliminating over 900 jobs.

Efficiency and economy became the new watchwords. Merchandise in stores was pared from 30,000 items to 17,000, with more of the remaining goods being pure U.S. Disney products. (The company had thought that European tastes might prefer more subtle items than the garish Mickey and Minnie souvenirs, but this was found not so.) The number of different food items offered by park services was reduced more than 50 percent. New training programs were designed to remotivate the 9,000 full-time permanent employees, to make them more responsive to customers and more flexible in their job assignments. Employees in contact with the public were given crash courses in German and Spanish.

Still, as we have seen, the problem had not been attendance, although the recession and the high prices had reduced it. Some 18 million people passed through the turnstiles in the first 20 months of operation. But they were not spending money as people did in the U.S. parks. Furthermore, Disney's high prices had alienated some European tour operators, and it diligently sought to win them back.

Management had hoped to reduce the heavy interest overhead by selling the hotels to private investors. But the hotels only had an occupancy rate of 55 percent, making them unattractive to investors. While the recession was a factor in the low occupancy rates, most of the problem lay in the calculation of lodging demands. With the park just 35 minutes from the center of Paris, many visitors stayed in town. About the same time as the opening, the real estate market in France collapsed, making the hotels unsalable in the short term. This added to the overhead burden and confounded business-plan forecasts.

While some analysts were relegating Euro Disney to the cemetery, few remembered that Orlando's Disney World showed early symptoms of being a disappointment. Costs were heavier than expected, and attendance was below expectations. But Orlando's Disney World turned out to be one of the most profitable resorts in North America.

Euro Disney had many things going for it, despite the disastrous early results. In May 1994, a station on the high-speed rail running from southern to northern France opened within walking distance of Euro Disney. This helped fill many of the hotel rooms too ambitiously built. The summer of 1994, the fiftieth anniversary of the Normandy invasion, brought many people to France. Another favorable sign for Euro Disney was the English Channel tunnel's opening in 1994, which potentially could bring a flood of British tourists. Furthermore, the recession in Europe was bound to end, and with it should come renewed interest in travel. As real estate prices became more favorable, hotels could be sold and real estate development around the park spurred.

Even as Disney chairman Michael Eisner threatened to close the park unless lenders restructured the debt, Disney increased its French presence, opening a Disney store on the Champs Elysees. The likelihood of a Disney pullout seemed remote, despite Eisner's posturing, because royalty fees could be a sizable source of revenues even if the park only broke even after servicing its debt. With only a 3.5 percent increase in revenues in 1995 and a 5 percent increase in 1996, these could yield $46 million in royalties for the parent company. 'You can't ask, 'What does Euro Disney mean in 1995?' You have to ask, 'What does it mean in 1998?' "[130]

Euro Disney, as we have seen, fell far short of expectations in the first 20 months of its operation, so much so that its continued existence was questioned. What went wrong?

A serious economic recession that affected all of Europe was undoubtedly a major impediment to meeting expectations. As noted before, it adversely affected attendance—although still not all that much—but drastically affected spending patterns, with frugality being the order of the day for many visitors. The recession also affected real estate demand and prices, thus saddling Disney with hotels it had hoped to sell at profitable prices to eager investors, thereby taking the strain off its hefty interest payments.

The company assumed that European visitors would not be greatly different from the visitors, foreign and domestic, to U.S. Disney parks. Yet, at least in the first few years of operation, visitors were much more price conscious. This suggested that those who lived within a two- to four-hour drive of Euro Disney were considerably different from the ones who traveled overseas, at least in spending ability and willingness.

Despite the decades of experience with the U.S. Disney parks and the successful experience with the newer Japan park, Disney still made serious blunders in its operational planning, such as the demand for breakfasts, the insistence on wine at meals, the severe peaks and valleys in scheduling, and even such mundane things as sufficient restrooms for tour bus drivers. It had problems in motivating and training its French employees in efficiency and customer orientation. Did all these mistakes reflect an intractable French mindset or a deficiency of Disney management? Perhaps both. But shouldn't Disney's management have researched all the cultural differences more thoroughly? Further, the park needed major streamlining of inventories and operations after the opening. The mistakes suggested an arrogant mindset by Disney management: "We were arrogant," concedes one executive. "It was like, 'We're building the Taj Mahal and people will come—on our terms.' "[131]

The miscalculations in hotel rooms and in pricing of many products, including food services, showed an insensitivity to the harsh economic conditions. But the greatest mistake was taking on too much debt for the park. The highly leveraged situation burdened Euro Disney with such hefty interest payments and overhead that the breakeven point was impossibly high, and even threatened the viability of the enterprise. See the previous Information Box for a discussion of the important inputs and implications affecting breakeven, and how these should play a role in strategic planning.

Were such mistakes and miscalculations beyond what we would expect of reasonable executives? Probably not, with the probable exception of the crushing burden of debt. Any new venture is susceptible to surprises and the need to streamline and weed out its inefficiencies. While we would have expected this to have been done faster and more effectively at a well-tried Disney operation, European, and particularly French and Parisian, consumers and employees showed different behavioral and attitudinal patterns than expected.

The worst sin that Disney management and investors could make would be to give up on Euro Disney and not to look ahead a few years. A hint of the future promise was Christmas week of 1993. Despite the first year's $920 million in red ink, some 35,000 packed the park most days. A week later on a cold January day, some of the rides still had 40-minute waits.

On March 15, 1994 an agreement was struck, aimed at making Euro Disney profitable by September 30, 1995. The European banks would fund another $500 million and make concessions such as forgiving 18 months interest and deferring all principal payments for three years. In return, Walt Disney Company agreed to spend about $750 million to bail out its Euro Disney affiliate. Thus, the debt would be halved, with interest payments greatly reduced. Disney also agreed to eliminate for five years the lucrative management fees and royalties it received on the sale of tickets and merchandise.[132]

The problems of Euro Disney were still not resolved by mid-1994. The theme park and resort near Paris remained troubled. However, a new source for financing had emerged. A member of the Saudi Arabian royal family agreed to invest up to $500 million for a 24 percent stake in Euro Disney. Prince Alwaleed had shown considerable sophistication in investing in troubled enterprises in the past. Now his commitment to Euro Disney showed a belief in the ultimate success of the resort.[133]

Finally, in the third quarter of 1995, Euro Disney posted its first profit, some $35 million for the period. This compared with a year earlier loss of $113 million. By now, Euro Disney was only 39 percent owned by Disney. It attributed the turnaround partly to a new strategy in which prices were slashed both at the gate and within the theme park in an effort to boost attendance, and also to shed the nagging image of being overpriced. A further attraction was the new "Space Mountain" ride that mimicked a trip to the moon.

However, some analysts questioned the staying power of such a movement into the black. In particular, they saw most of the gain coming from financial restructuring in which the debt-ridden Euro Disney struck a deal with its creditors to temporarily suspend debt and royalty payments. A second theme park and further property development were seen as essential in the longer term, as the payments would eventually resume.

To the delight of the French government, plans were announced in 1999 to build a movie theme park, Disney Studios, next to the Magic Kingdom, to open in 2002. It was estimated that this expansion would attract an additional 4.2 million visitors annually, drawing people from farther afield in Europe. In 1998, Disneyland Paris had 12.5 million visitors, being France's number-one tourist attraction, beating out Notre Dame.

Also late in 1999, Disney and Hong Kong agreed to build a major Disney theme park there, with Disney investing $314 million for 43 percent ownership while Hong Kong contributed nearly $3 billion. Hong Kong's leaders expected the new park would generate 16,000 jobs when it opened in 2005, certainly a motivation for the unequal investment contribution.[134]

The Walt Disney Studios theme park opened in March 2002, as planned. It blended Disney entertainment with the history and culture of European film. This reflected a newfound cultural awareness, and efforts were focused largely on selling the new park through travel agents, whom Disney initially neglected in promoting Disneyland Paris. The timing could have been better, as theme parks were reeling from the recession and the threat of terrorist attacks. A second Disney park opened in Tokyo in 2001 and was a smash hit. But the new California Adventure Park in Anaheim, California had been a bust.[135]

By the end of 2004, Euro Disney was again facing record losses. Partly this was because of the resumption of full royalty payments and management fees to Walt Disney Co. But deeper problems were besetting it. Attendance had remained flat at about 12.4 million. The new Disney Studios Park opened to expectations of four million visitors, but only 2.2 million came in 2004, and many complained that it did not have enough attractions. Three major new attractions are scheduled to open in 2006 to 2008, with two of these for the Studios Park. For the first three months of 2005, the popular Space Mountain was closing for upgrading. In this scenario, the company planned "regular admission-price increases." "The business model does not seem viable," observed one portfolio manager.[136]

Something happened in January 2005. The French government realized that they really wanted Euro Disney to succeed. Despite the American-bashing that came after President Bush's invasion of Iraq and President Jacques Chirac's calling the spread of American culture an "ecological disaster," another French preoccupation surfaced: the top priority of reducing France's high unemployment. Euro Disney's site was the biggest employer in the Paris region with 43,000 jobs, and it had created a booming urban sprawl on once-barren land.

Now Prime Minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin vowed not to let Euro Disney go bankrupt: "We are grateful to the American people and have lots of respect for their culture." A state-owned bank contributed around $500 million in investments and loan concessions. The hope was that new and expensive attractions and a better economic climate would bring a turnaround. Still, if the Tower of Terror ride and other new attractions failed to attract millions of new visitors, Disney and the French government might have to pour more money into this venture that once seemed such a sure thing. Under consideration was to open Charles de Gaulle airport to more low-cost airlines to make Euro Disney a cheaper destination.[137]

As the economy continued to sputter in 2009, revenue and operating income in all segments of the company also declined. Interestingly, attendance at domestic parks rose 3 percent due to various discounts and promotions, and less people working, but operating income fell 19 percent for the third quarter of 2009.[138]

Disney also had a lot at stake in the success of Euro Disney. Failure would hurt its global brand image as it prepared to expand into China and elsewhere in the Far East. Perhaps the lessons learned in Paris of trying to keep visitors longer while saving on fixed costs would transfer. The following Information Box: Disneyland Hong Kong, suggests that some lessons learned in Europe and the early years in Hong Kong might finally be assimilating. Or are they?

Invitation to Make Your Own Analysis and Conclusions

How do you account for Disney management erring so badly, both at the beginning, and even for years afterwards? Any suggestions?

How could the company have erred so badly in its estimates of spending patterns of European customers?

Could a better reading of the impact of cultural differences on revenues have been achieved?

What suggestions do you have for fostering a climate of sensitivity and goodwill in corporate dealings with the French?

How do you account for the great success of Tokyo Disneyland and the problems of Euro Disney? What are the key contributory differences?

Do you believe that Euro Disney might have done better if located elsewhere in Europe rather than just outside Paris? Why or why not?

"Mickey Mouse and the Disney Park are an American cultural abomination." Evaluate this critical statement.

Consider how a strong effort to woo both European consumers and middlemen, such as travel agents, tour guides, even bus drivers, might have been made. How effective would this likely be?

Discuss the desirability of raising admission prices at the very time when attendance is static, profits are nonexistent, and new attractions are months and several years in the future.

As the staff assistant to the president of Euro Disney, you already believe before the grand opening that the plans to use a skimming pricing strategy and to emphasize luxury hotel accommodations is ill advised. What arguments would you marshal to try to persuade the company to offer lower prices and more moderate accommodations? Be as persuasive as you can.

It is six months after the opening. Revenues are not meeting target, and a number of problems have surfaced and are being worked on. The major problem remains, however, that the venture needs more visitors and/or higher expenditures per visitor. Develop a business model to improve the situation.

How would you rid an organization, such as Euro Disney, of an arrogant mindset? Assume that you are an operational VP, and have substantial resources, but not necessarily the eager support of top management.

It is two years after the opening, Euro Disney is a monumental mistake, profit-wise. Two schools of thought are emerging for improving the situation. One is to pour more money into the project, build one or two more theme parks, and really make this another Disney World. The other camp believes more investment would be wasted at this time, that the need is to pare expenses to the bone and wait for an eventual upturn. Debate the two positions.

Can you criticize the present business plan for Euro Disney? Do you think the lesson presumably learned should transfer well to the Far East?

What is the situation with Euro Disney today? Are expansion plans going ahead? How is Disneyland Hong Kong doing? Have any more recent parks been opened, and if so, are they encountering any problems? How well did Disney weather the economic decline? Have sales and profits fully recovered?

[123] Steven Greenhouse, "Playing Disney in the Parisian Fields," New York Times, February 17, 1991, Section 3, pp. 1, 6.

[124] Ibid., p. 6.

[125] Peter Gumbel and Richard Turner, "Fans Like Euro Disney but Its Parent's Goofs Weigh the Park Down," Wall Street Journal, March 10, 1994, p. A12.

[126] James Sterngold, "Cinderella Hits Her Stride in Tokyo," New York Times, February 17, 1991, p. 6.

[127] "Ailing Euro May Face Closure," Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 1, 1994, p. E1.

[128] Gumbel and Turner, p. A12.

[129] Ibid.

[130] Lisa Gubernick, "Mickey N'est Pas Fini," Forbes, February 14, 1994, p. 43.

[131] Gumbel and Turner, p. A12

[132] Brian Coleman and Thomas R. King, "Euro Disney Rescue Package Wins Approval," Wall Street Journal, March 15, 1994, pp. A3 A5.

[133] Richard Turner and Brian Coleman, "Saudi to Buy as Much as 24% of Euro Disney," Wall Street Journal, June 2, 1994, p. A3.

[134] "Hong Kong Betting $3 Billion on Success of New Disneyland," Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 3, 1999, p. 2C; Charles Fleming, "Euro Disney to Build Movie Theme Park Outside Paris," Wall Street Journal, September 30, 1999, pp. A15, A21.

[135] Bruce Owwall, "Euro Disney CEO Named to Head Parks World-Wide," Wall Street Journal, September 30,2002, p. B8; Paulo Prada and Bruce Orwall, "A Certain 'Je Ne Sais Quoi' at Disney's New Park," Wall StreetJournal, March 12, 2002, pp. B1 and B4.

[136] Jo Wrighton, "Euro Disney's Net Loss Balloons, Putting Financial Rescue at Risk," Wall Street Journal, November 10, 2004, p. B3.

[137] Jo Wrighton and Bruce Orwall, "Despite Losses and Bailouts, France Stays Devoted to Disney," WallStreet Journal, January 26, 2005, pp. A1 and A6.

[138] Ethan Smith, "Disney's Profit Decline Slows to 26%, Wall Street Journal, p. B3.

[139] Geoffrey A. Fowler, "Main Street, H.K.," Wall Street Journal, January 23, 2008, pp. B1 and B2.

[140] Gumbel and Turner, p. A1.