7

WORKING WITH GLOBAL TEAMS

Body Language in a Multicultural World

On a speaking tour a few years ago, I traveled from the United Arab Emirates to China to India to Malaysia to the Philippines to Indonesia—and it seemed to me that in each country, the audience was arriving later and later. My speech in Jakarta was scheduled for 7:00 P.M. “Just ignore that announcement,” I was advised. “We tell people to get here at seven, hoping they will arrive by eight. But just to be on the safe side, we never begin the program before nine.”

Contrast that to a recent experience in Toronto, where my session was scheduled to open a conference at 8:00 A.M. In order to check the audiovisual equipment, I arrived an hour early, only to see a line of people already standing outside the auditorium. Concerned that I had misunderstood the agenda, I grabbed the meeting planner. “Don't worry,” she assured me, “you've got plenty of time. We Canadians just have a habit of getting places early.”

Here's the question: Which was right—the Indonesian concept of “rubber time” or the Canadian view of promptness?

Your answer, of course, depends on the cultural standards you are dealing with—because different cultures relate to time very differently. And the concept of time is only one of the nonverbal variants you will need to consider in order to work effectively with colleagues and associates whose cultural norms are different from your own.

Leadership today demands wide cultural acumen—not just because you have to participate increasingly in global teams, but also because the workforce within your own national borders is growing more diverse, ethnically and culturally. On any given business day, you can find yourself communicating face-to-face, over the phone, by e-mail, or by teleconference with people whose customs and cultures differ dramatically from your own.

This chapter and the next will help you communicate more effectively in a multicultural world by familiarizing you with the ways people from different cultures experience the world, and how those differences influence their nonverbal behavior in the business arena. We'll look at the distinction between so-called high- and low-context cultures, the important conceptual difference between time as a commodity and time as a constant, reserve versus effusion in the conduct of business, the subtle art of formal and informal behavior, why certain body language feels so right in one culture and so wrong—or even offensive—in another, and finally, which nonverbal signals are universal to all cultures.

CULTURE

In this chapter, the word culture refers primarily to a set of shared social values and assumptions that determine what is acceptable or “normal” behavior within a defined society (a nation, commonwealth, tribe, religious community, and so on). These values also serve a given society as a benchmark by which to judge the behavior of others. It is this second point you need to pay careful attention to when you're out there in the global arena. One little social blunder—an inappropriate remark, gesture, or expression—could cost you a contract, a vital introduction, or even an entire project. And without some basic understanding of the culture you're working in, you might not even know you've committed it!

Of course, you can't automatically presume that everyone you meet from a particular culture will exhibit identical nonverbal communication traits. Cultural stereotypes are valid only in that they provide clues about what to expect in general. Nor can you expect to fully understand all the layers and shades of meaning transmitted by nonverbal behavior in another culture. And you certainly can't view the behavior of others totally free of your own cultural bias—nor can others who are observing you. But you can adapt with reasonable success to almost any unfamiliar cultural environment by watching, listening, exercising a little patience and tolerance, and quietly modulating your own behavior in line with some of the basics that follow here.

High Context, Low Context

One very useful observational tool for dealing with an unfamiliar environment derives from a system of classification created by cultural anthropologist Edward T. Hall, which states that all cultures can be situated in relation to one another in terms of the styles in which they communicate. Low-context cultures (LCCs) communicate predominately through verbal statements and the written word. Low-context communication is explicit, direct, and precise, with little reliance on the unstated or implied. In high-context cultures (HCCs), communication depends more on sensitivity to nonverbal behaviors (body language, proximity, and the use of pauses and silence) and environmental cues, such as the relationship of the participants, what has occurred in the past, who is in attendance, and the time and place of the communication.1

Continuum of High-Context to Low-Context Cultures

Source: L. Copeland and L. Griggs, 2001, Going International: How to Make Friends and Deal Effectively in the Global Marketplace (New York: Random House), p. 107.

Negotiators from LCCs tend to focus more on closing the deal, whereas those from HCCs are looking to build a relationship. When communicating across the “context divide” in global team meetings, LCC members might profit from taking extra time to get to know their HCC counterparts; HCC individuals might benefit from being more direct with LCC teammates, and understanding their need for “measurable progress.” Everyone on the team could benefit from an open discussion and a deeper understanding of their cultural differences and similarities. The point, of course, isn't to abandon your cultural preferences but to increase cross-cultural effectiveness.

E-Mail from Japan

When I worked at a US-owned company, there was a team meeting. The marketing manager was the only American in attendance. The rest of the team (another marketing manager, engineers, designers, and manufacturers) came from Taiwan, France, Japan, Iran, and elsewhere. Most of us spoke very broken English, but the meeting was exciting and all were happy with the result—except the American. After the meeting he came to me and said “I'm the only guy who doesn't get it, so why don't you e-mail me a report?” All of us except for this one manager could understand each other through facial expressions, gestures and so on. Now that I think back, it seems like he relied too much on the verbal aspect of the communication.

—Kazuhiro Amemiya, Japan

Time—Commodity or Constant?

In the United States, we think of time as a linear commodity to “spend,” “save,” or “waste.” Other cultures (including Italy, Brazil, and Japan) view time as a constant flow to be experienced in the moment, and as a force that cannot be contained or controlled. Whichever view you take can influence the way you conduct business.

When time is a commodity, adhering to a schedule becomes very important. I've seen the American fixation on timelines play right into the hands of negotiators from other cultures. A Japanese executive explained, “All we need to do is find out when you are scheduled to leave the country—and, by the way, it amuses us that you arrive with your return passage already booked—then we wait until right before your flight to present our offer. You are so anxious to stay on schedule, you'll give away the whole deal.”

In cultures where the flow of time is a constant, it is viewed as a sort of circle in which the past, present, and future are all interrelated. In fact, in the Chinese languages there are no tenses to express past and future. Instead, “the three dimensions of time are always present and can be distinguished only through context.”2 Any important relationship is a durable bond that goes back and forward in time. In these cultures, relationships are pivotal to doing business, and it is often viewed as grossly disloyal not to favor friends and relatives in business dealings.

It's About Time

There's a joke about an American and a Chinese businessman sitting next to each other on a park bench in Hong Kong. The American says, “Well, you know I've been in Hong Kong for my company for thirty years. Thirty years! And in a few days they are sending me back to the States.” The Chinese executive replies, “That's the problem with you Americans: here today and gone tomorrow.”

Reserved or Effusive?

People from reserved cultures (like the Japanese, Chinese, Scandinavians, and Finns) tend to encourage speaking up only when there is something relevant to add to the conversation—and may have problems relating to people from cultures who constantly talk about seemingly irrelevant topics. Reserved cultures also tend to mask their feelings by keeping their emotional displays in check.

Effusive cultures encourage people to talk a lot as a means of indicating their warmth, passion, and interest. These cultures tend to interrupt more often and to avoid silence. They also tend to be more expressive and animated and to use larger and more frequent gestures. Examples of effusive cultures include the Arab countries, Italy, and Latin America.

If you're wondering how such an insignificant behavioral distinction could possibly have an impact on your organization's business decisions, consider the following: An American-born Japanese IT manager requested a relocation to work at his company's Tokyo office. Excited about the possibility, he flew to Japan and interviewed with the local management team. His request was turned down. The reason? He was “too enthusiastic.”

A Chinese-born, U.S.-educated, and highly qualified salesman was being considered for the job of sales manager for a new office in Shanghai. The American boss who conducted the interview decided that the salesman didn't demonstrate the “drive and aggression” needed to lead a sales department.

Of course, both evaluations may have been correct. But it is much more likely that the characteristics the interviewers wanted to see from the candidates were as much a reflection of their own respective cultures as an indicator of qualifications necessary for these jobs.

Formal and Informal

A U.S. executive in France made a conspicuous effort to socialize with lower-ranking staff members. His entirely logical intent was to boost morale, but his actions all but destroyed it. What the U.S. executive didn't know was that the French have a more structured and formal business culture, and that this kind of interlevel fraternizing is frowned on.

Should he have known this? Well, it would have helped his team-building efforts. Could he have known this? Yes, he could have—by being a little more observant and a little less sure of himself until he knew his business environment a little bit better. For a newcomer stepping into a formal arena like the French business culture, employing a small dash of reticence is always a good tactic in the beginning. Showing everybody what a great guy you are sometimes isn't such a great idea.

In informal cultures (like the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland), people believe that inequality of social status or class should be minimized. The hierarchy in an organization is based more on differences in roles; individual ability and performance are most important. But in formal cultures (including European and Asian nations, the Arab world, the Mediterranean region, and Latin America), people are more likely to be treated with greater or less deference according to their social status, family background and connections, age, education, titles, degrees, and wealth.

In formal cultures, business protocol is highly valued, whereas it is seen as something inconvenient or tedious in informal cultures. People from informal cultures may regard their formal counterparts as distant, stuffy, pompous, or arrogant. People from formal cultures often find informality to be insulting. For example—and yes, I've seen all these behaviors in high-level global meetings over the years—if you slouch, chew gum, call people “pal” or “buddy” or by their first name on first acquaintance, cross your legs in an open-legged position, stretch out, or wear jeans and a tee shirt when everyone else is in a suit, you may be labeled “offensively informal.” Or as one of my Malaysian clients explained with polite understatement, “We consider it rude and disrespectful to assume an intimacy that doesn't yet exist.”

Assumptions you make about other cultures, even with the best of intentions, can also backfire if you haven't taken the time to verify them: “Once I attended a training session where the Canadian facilitator came dressed in flip-flops, long beads, and a white cotton breezy shirt. It was her first time in the Caribbean, and she made some terribly inaccurate assumptions about our culture. You see, everyone else in the room was dressed in a business suit” (Judette Coward-Puglisi, Trinidad and Tobago).

CROSS-CULTURAL BODY LANGUAGE

Some nonverbal signals are unique to a particular culture. Emblematic gestures fall into this category. For example, what we in the United States think of as a positive gesture, the “OK” sign with thumb and forefinger together creating a circle, has very different meanings in other cultures. In France it means “worthless” or “zero,” in Japan it stands for money, and in other countries it represents a lewd or obscene comment.

There are, however, many nonverbal signals that cross cultural lines. In fact, body language that is controlled by the limbic brain (such as the freeze-fight-flight response to threat, blushing when embarrassed, and the need to self-pacify when under stress) can be seen around the world. We all use barriers—desks, crossed arms, turns to the side, hands clasped tightly—as methods of protection or making ourselves less vulnerable. And, although these may manifest differently, all cultures use gesture to add meaning to words, replace words, and (consciously or unconsciously) deliver unspoken information about the attitudes and feelings of the sender. One of these we've previously discussed is the “eyebrow flash,” the universal body language cue that involves a sudden and quick raising of the eyebrows and widening of the eyes that occur when people encounter those they recognize and like.

Nonverbal communication is both instinctive (innate) and acquired (culturally determined). There are basic human emotions that are instinctive and universal, but their display is restricted by the “norms” of a particular culture—and the stimulus that triggers those emotions may also vary from culture to culture.

As we saw in Chapter One, scientists studied the aftermath of judo matches from the 2004 Olympic and Paralympic Games, comparing the behavior of winning and losing judo players. They found that victory looked the same (throwing their heads back, thrusting their arms in the air, puffing out their chests, and flashing big grins) across cultures. This was true even among athletes who were born blind and could never have learned the behavior from mimicking others.

There was a difference in the expression of shame, however. Among Western cultures, sighted athletes tended not to physically express shame—whereas their blind counterparts did. Researchers attributed this to the fact that shame is stigmatized in Western cultures, so repressing this emotion was a learned response.3

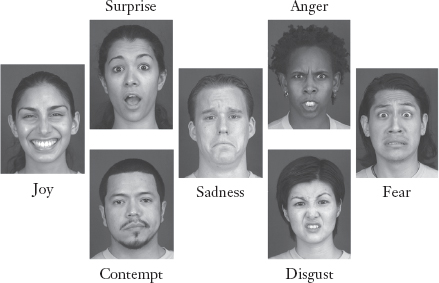

Universal Emotional Expressions

There is one area of body language that is identical in all cultures—the seven basic emotions that people around the world express, recognize, and relate to in the same way. Discovered and categorized by Paul Ekman and his colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, the universal emotional expressions are joy, surprise, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and contempt.4 Here is how you can identify them:

- Joy. The muscles of the cheeks rise, eyes narrow, lines appear at the corners of the eyes, and the corners of the mouth turn up.

- Surprise. The eyebrows rise, and there is a slight raising of upper eyelids and dropping of the lower jaw.

- Sadness. The eyelids droop as the inner corners of the brows rise and (in extreme sorrow) draw together, and the corners of the lips pull down.

- Anger. The eyebrows are pulled together and lowered, the lower eyelid is tensed, the eyes glare, and the lips tighten, appearing thinner.

- Fear. The eyebrows draw together and rise, the upper eyelid rises, the lower eyelid tenses, and the lips stretch horizontally.

- Disgust. The nose wrinkles, the upper lip rises, and the corners of the mouth turn down.

- Contempt. This is the only unilateral expression. The cheek muscles on one side of the face contract, and one corner of the mouth turns up.

Universal emotional expressions

Whenever any of these emotions is felt strongly, its display is intense and can last up to four seconds. But, depending on a variety of influences (including an individual's cultural background), you may not see your team members exhibiting this stronger version. Emotional displays in corporate settings are often more subtle and fleeting.

Reading faces is a matter not just of identifying static expressions but also of noticing how faces subtly begin to change. (You do this every day without being aware of it. When you are in face-to-face exchanges, you watch the other person's changing expressions for all kinds of reactions and cues in order to gauge responses to what you just said.) Subtle expressions are emotions just starting to be shown, emotions experienced with a lower intensity, or emotions partially inhibited. Subtle versions of expressions involve the same facial muscles as their stronger counterparts, but are much less obvious. On more than one occasion, I've seen a slight expression of anger or disgust between colleagues, which has spoken volumes about the real underlying feelings between the two people. (I tend to watch the eyes. The small muscles around the eyes are often the site of real emotional giveaway—one part of the face that reacts before you even know how you feel about something that's been said or implied.)

Subtle expressions also contain a lot of useful information for managers and executives. David Matsumoto, founder of Humintell and a renowned expert in the field of nonverbal communication and emotions, has a “Subtle Expression Recognition Training” that was originally developed for government agencies. But I also recommend it to my leadership clients.5 Leaders who develop their ability to decipher the not-so-obvious emotional reactions of team members gain a distinct advantage in establishing relationships, building rapport, eliciting information, and tracking how people really feel.

Micro expressions (lasting less than one-fifth of a second) are another way that an observer can get a glimpse into a person's true emotional state. But unless you are a trained expert (Humintell also provides training in this) or naturally gifted at spotting these fleeting visual impulses, they probably won't be helpful in a business setting. I'm not particularly adept at spotting micro expressions in real time, but I have “caught” several of them when analyzing people on videotape, when I could view an action repeatedly or slow it down.

Faked emotional reactions are more readily spotted. In general, expressions that are not genuine can be identified by the following behaviors:6

- A forced or faked expression does not use all the muscles in the face typically associated with that expression. One example previously mentioned is the smile that includes the mouth but does not involve the eye muscles.

- Because all real expressions (with the exception of contempt) are symmetrical, any other asymmetrical expression should be suspect.

- An expression that is of an unusually long duration (more than five seconds) is typically not genuinely felt. Most real expressions last only for a few seconds.

LESSONS LEARNED

I've learned a lot as I've observed global team meetings, and the most important lesson I can pass on to U.S. leaders is not to rush in with an American “take-charge attitude.” In Hong Kong, I watched a newly arrived American executive meet with his Chinese team members—and destroy in five seconds the delicate relationship that the incumbent had taken over a year to build. Undoubtedly the new exec thought he was coming across as a hard-charging young businessman (which might have been the case back in the States), but in this culture, his actions were seen as rude, insensitive, and overbearing.

Like anyone else dealing with an international clientele, I have made my share of cultural faux pas. One particularly memorable one was when I started a global meeting with an “icebreaker” exercise—a tactic that we in the United States are particularly fond of. (After all, “time is money,” so we need to find quick ways to get this “relationship-building stuff” in full swing.) I overheard a European participant say with a sigh, “Not another American icebreaker. Why don't they just wait until we thaw?”

I've also found that my international clients have been extremely generous in overlooking my cultural mishaps. As one client told me, “It will be fine, Carol. We know your heart is in the right place.” Aretha Franklin was right—it all starts with R-E-S-P-E-C-T. If you show a genuine respect for other cultures' norms and values, and if your heart's in the right place—even if you make an occasional blunder—it will be fine.