4

COLLABORATION

Body Language Cues for Inclusion

Sharon entered the conference room, took her place at the head of the table, put down her coffee cup, opened her laptop, greeted her new management team with remarks about the importance of collaboration, and asked individuals to introduce themselves. She had worked previously with some of the managers there, and she nodded, smiled, and made eye contact with each before calling the meeting to order. But then, as other team members began to speak, she seemed to lose interest in what was going on; she frequently looked away to check her computer screen, walked over to the coffee table for a refill, and, when her cell phone buzzed, excused herself to answer—at length. Then she announced a break, during which she asked me, in all seriousness, for a critique of her leadership style.

I wish I'd had this chapter to give her instead!

Critical elements of a company's competitiveness are the potential of its people, the quality of the information those people possess, and their willingness to share knowledge with others in the organization. The leadership challenge is to link these components as tightly as possible to facilitate increased collaboration and knowledge sharing in teams, in departments, and right across the company.

This chapter will explain how we are hardwired to connect with colleagues, how mirroring creates empathy, what the body language of inclusion means, how damaging the exclusion of individuals can be, the importance of how you say what you say, the importance of space, a new definition of “dress for success,” what your office says about you, and why familiarity breeds collaboration.

THE UNIVERSAL NEED FOR COLLABORATION

One of my most requested speaking topics is “Harnessing the Power of Collaboration.” The topic's popularity stems from corporate clients around the world realizing that the “silo mentality” and knowledge-hoarding behaviors are wasting the kind of collective brainpower that could save their organizations billions. Or lead to the discovery of a revolutionary new process or product. Or, in the current economic climate, help keep the company afloat when others are sinking!

And it's not just corporate profits that suffer when collaboration is weak: the workforce loses something too.

Individuals lose the opportunity to work in the kind of inclusive environment that energizes teams, releases creativity, and makes working together both productive and joyful.

Ouch! You Excluded Me

Naomi Eisenberger, a social neuroscience researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, designed an experiment to find out what goes on in the brain when people feel rejected by others.1 She had volunteers play a computer game while their brains were scanned by fMRI machines. Subjects thought they were playing a ball-tossing game over the Internet with the two other people. There was an avatar (a computerized graphic that represents a person in a virtual environment) for the volunteer, and avatars for two other people.

About halfway through this game of catch, the subject stopped receiving the ball, and the two other players threw the ball only to each other. In reality, there were no other human players, only a computer program designed to exclude the test subject at some point. But even when they learned the truth, the players said they still felt angry, snubbed, or judged, as if they had been left out of the game for some personal reason.

Even more interesting to the neuroscientists was what was happening in the subjects' brains. When people felt excluded, there was corresponding activity in the dorsal portion of the anterior cingulate cortex—the neural region involved in the “suffering” component of pain. In other words, the feeling of being excluded provoked the same sort of reaction in the brain that physical pain might cause.

As the research highlights, it really doesn't take much to make people feel left out. The nonverbal signals that make someone feel unimportant are often slight: letting your gaze wander while he or she is talking, or angling your shoulders even a quarter-turn away. Trivial actions (like Sharon's behavior with her new team), if they happen only infrequently, are most likely not going to demoralize a team member. But if you are continually offhanded, neglectful, or unresponsive to certain individuals, your behavior will not go unnoticed, and it can be seriously destructive of the collaboration you are seeking to foster in the group. It can also be very hurtful. Team members who feel that they and their ideas are being ignored will simply withdraw and stop contributing, and the sense of unease created by that withdrawal will broadcast itself subliminally to the whole group. Leaders with inclusive body language create an emotional environment that supports collaboration and high performance. But when a leader appears to play favorites by using more positive nonverbal signals with some people than with others, when a leader's body language excludes an individual, and when those behaviors result in “hurt” feelings—the pain is very real.

A Hunger for Connection

“Loneliness and the feeling of being unwanted is the most terrible poverty.”

—Mother Teresa2

WIRED TO CONNECT

The roots of cooperation go back to our prehistory as a matter of survival. Belonging is not only a motivating component of workplace collaboration but also the brain's key driver. Our brains have evolved to be social and collaborative—constantly assessing what others may think or feel, how they are responding to us, whether we feel safe with them, and whether they feel safe with us.

Social animals thrive together—not separately. We have a need for belonging that is powerful and primitive. We love contributing, and we love being thanked. When others show us respect and appreciation, it triggers the same centers in the brain that are activated when we eat chocolate or have sex. Understanding this dynamic gives you insight into the intrinsic rewards of collaboration—and why it is so important that your body language signals are open and positive.

Mirror Neurons

As noted in Chapter Three, empathy can be a powerful motivator in the workplace. The field of neuroscience that holds the most promise for understanding collaborative leadership is the study of mirror neurons and how empathy develops in the brain. In the late 1980s, researchers at the University of Parma in Italy found that the brain cells of macaque monkeys fired in the same way whether they were making a particular motion (such as reaching for a peanut) or watching another monkey or human make that movement. In terms of motor cell activity, the monkey's brain could not tell the difference between actually doing something and seeing it done. The scientists named those brain cells “mirror neurons.”3

You can spot mirror neurons in action when a newborn baby looks up and the mother smiles at him or her. We now know that if you monitored the infant's brain, mirror neurons would have fired on seeing the mother's smile—and those cells would have created the same pattern as they would if the baby had actually smiled. And indeed, within the first hours of life, the infant will begin to mimic those maternal smiles.

In an organizational context, employees search for cues from leaders and mimic their behaviors, both consciously and unconsciously. A key insight from mirror neuron research is the reinforcement of an old management truism: modeling desirable behaviors will encourage employees to follow suit. If you want your team to collaborate, then first you need to become a positive example of collaboration. Or as Mahatma Gandhi said, you need to “be the change you want to see in the world.”

Before the discovery of mirror neurons, it was generally believed that we used analytical thought processes to interpret and predict other people's motives and actions. Now, however, the prevailing theory is that we understand each other not by analysis but, as mentioned in previous chapters, through emotion. In human beings, mirror neurons not only simulate actions but also reflect intentions and feelings. They thus play a key role in our ability to socialize and empathize with others. By reading body language signals (especially facial expressions) and automatically interpreting the emotion behind them, we get an intuitive sense of the world around us—without having to think about it.

Here's how it works in a corporate setting. Mirror neurons fire when you see an emotion expressed on a team member's face—or read it in his or her gestures or posture. You then subconsciously place yourself in the other person's “mental shoes” and begin to recall and experience that same emotion. It's your mirror neurons that give you the capacity to experience the joys and sorrows of others and to connect with them on an emotional level. When as a leader you mirror team members' facial expressions and body positions, you instantly communicate empathy and signal that you understand the feelings of the people around you and will take those feelings into account as you decide how to respond. This also explains why mirroring and the resultant feeling of being “connected” are such powerful parts of building a collaborative team.

Since the discovery of mirror neurons, various studies have been conducted to validate their effect. In a recent experiment, volunteers were (ostensibly) asked for their opinions about a series of advertisements. A member of a research team mimicked half the participants, taking care not to be too obvious. A few minutes later, the researcher “accidentally” dropped six pens on the floor. Participants who had been mimicked were two to three times more likely to pick up the pens. The study concluded that mimicry had not only increased goodwill toward the researcher (in a matter of minutes) but also prompted an increased social orientation in general.4

Synchrony and Cooperation

At a leadership conference last year, the meeting was opened by a group of drummers who led the entire audience in synchronous drumming. It was a great choice for a meeting intended to enhance collaboration. If that seems odd to you, consider the following….

Marching, singing, dancing (and drumming) are all examples of activities that lead group members to act in synchrony with each other. Stanford University conducted research that showed that synchronous activity motivates members of a group to contribute toward the collective good. Across three experiments, people acting in synchrony with others cooperated more in subsequent group economic exercises, even in situations requiring sacrifice on a personal level from the group. Their results suggest that synchrony can increase cooperation by strengthening social attachment among group members.5

How Do You Listen?

As part of a research project, a group of undergraduate students at VU University Amsterdam watched an eight-minute film, after which they were asked to describe it as fully as possible to other students. The listeners were actually research assistants, and for half the participants they assumed a positive listening style (smiling, nodding, maintaining an open bodily position); for the other participants they assumed a negative listening style (frowning and unsmiling). Participants describing the film to positive listeners used more abstractions, describing aspects of the film that couldn't be seen, such as a character's thoughts and emotions. They also included more of their own opinions about what the film was trying to say. In contrast, participants speaking to negative listeners focused solely on objective facts and concrete details.6

The theory is that the smiles and nods of a listener signal interest and agreement, which in turn encourage the speaker to share more personal insights and speculation. Negative body language triggers a threat response that causes the speaker to pull back into the relative “safety” of facts.

What this means in the context of collaboration and leadership is that by merely adjusting his or her body language, a leader can actually influence how team members process and report information.

SIX BODY LANGUAGE TIPS FOR INCLUSION

The body language of inclusion is pretty much what you'd expect: it includes eye contact, smiling, head nods, and body orientation. But don't get fooled. These seemingly inconsequential behaviors are so powerful that they may dictate your success or failure as a collaborative leader. Here are six ways to use body language to enhance collaboration.

First Tip: Check Your Expectations

Pygmalion in the Classroom, one of the most controversial publications in the history of educational research, shows how a teacher's expectations can motivate student achievement. In this classic study, prospective teachers were given a list of students who had been identified as “high achievers.” The teachers were told to expect remarkable results from these students, and at the end of the year, the students did indeed show sharp increases in their IQ test scores.7

In reality, these children had been chosen at random, not as a result of any testing. It was the teachers' belief in their potential that was responsible for the extraordinary results. The children were never told they were high achievers, but this message was delivered subtly and nonverbally through such behaviors as facial expressions, gestures, touch, and spatial relationships (the distance between teacher and student).

This self-fulfilling prophecy isn't only operational in the classroom. Tel Aviv University professor Dov Eden has demonstrated the power of the Pygmalion effect in all sorts of work groups, across all sectors and industries. It almost sounds too simple to be true, but Eden found that if supervisors or managers hold positive expectations about the performance of the people they lead, that performance will improve.8

Collaboration is based on trust and empowerment, and your willingness to trust and empower team members depends on whether you believe they will be able to take on that responsibility and succeed. Your expectations (and the way those expectations are broadcast through your body language) are a key factor in how well people perform on your team.

Second Tip: Activate Your Smile Power

A genuine smile not only stimulates your own sense of well-being but also tells those around you that you are approachable, cooperative, and trustworthy. A genuine smile comes on slowly, crinkles the eyes, lights up the face, and fades away slowly. In contrast, a counterfeit or “polite” smile comes on quickly and never reaches the eyes.

Some nonverbal behaviors can bring out the best in people. Smiling is one of them. It makes you feel good and produces positive physiological changes in your body temperature and heart rate. But, most important for a collaborative leader, smiling directly influences how other people respond to you. When you smile at someone, he or she almost always smiles in return. And because facial expressions trigger corresponding feelings, the smile you get back actually changes that person's emotional state in a positive way.

Third Tip: Use Your Head

Collaboration depends on participants' willingness to speak up and share their ideas and insights. Your nonverbal signals can either increase participation or shut it off.

The next time you are in a meeting where you're trying to encourage a team member to continue speaking, nod your head using clusters of three nods at regular intervals. I've found that people will talk much more than usual when the listener nods in this manner.

Head tilting is another signal that you are interested, curious, and involved. The head tilt is a universal gesture of giving the other person an ear. As such, head tilts can be very positive cues when you want to encourage people to expand on their comments.

Fourth Tip: Look at People When They Speak

Eye contact is a powerful motivator to encourage speaking, because people feel that they have your attention and interest as long as you are looking at them. The power of eye contact to direct a conversation is evident even when the “listener” is a robot.

Scientists from Carnegie Mellon University, in collaboration with researchers from Japan's Osaka University and from ATR Intelligent Robotics and Communication Laboratory, found that a robot's eye movement is key to guiding the flow of a conversation with more than one person. The robot (called Robovie) used for the experiments was given the ability to combine gaze with speech.

Having been programmed to play the part of a travel agent, Robovie was able to control the flow of a booking negotiation quite effectively with strategic eye contact. When it looked equally at two people, they took turns speaking. Those at whom Robovie only glanced spoke less, and those who were ignored completely spoke the least. This pattern was consistent about 97 percent of the time.9

As a leader, you set the tone for the meeting. Body language that signals boredom or disinterest will ensure that team members are disinclined to share their knowledge and viewpoints. If you want someone to speak up, avoid the temptation to check your text messages, your watch, or how the other participants are reacting. Instead, focus on whoever is speaking to make sure that he or she feels that you are listening.

Fifth Tip: Use the “Ultimate Connective Gesture”

When you make an uplifting statement (for example, “This is a wonderful opportunity”), gesture toward the listener with an upward open palm and then casually pull your hand back toward your body. In the example, you would start your gesture toward the other person as you say the word “wonderful” and bring the gesture toward you as you say the word “opportunity.” When you do this, you are nonverbally connecting the two of you in the most positive and inclusive way.

Sixth Tip: Remove Barriers

Face people directly. Even a quarter-turn away creates a barrier (the “cold shoulder”), signaling a lack of interest and causing the speaker to shut down. Physical obstructions are especially detrimental to the effective exchange of ideas. Take away anything that blocks your view or forms a barrier between you and the rest of the team. Close your laptop, turn off your cell phone, put your purse or briefcase to the side.

And if you think it makes you look more efficient (or important) to be continually checking your laptop or cell phone for messages, think again. As one member of a management team recently told me, “There's this senior exec in our department who has a reputation of being totally addicted to his BlackBerry. He is constantly on the machine during internal meetings. When he finally focuses on others, peers make jokes about his ‘coming back to earth.’ We know he's not tracking the conversation because he keeps asking questions that have been already responded to. The result is that when he does contribute, he has no credibility.”

Even at a coffee break, be aware that you may create a barrier by holding your cup and saucer in a way that seems deliberately to block your body or distance you from others. A very successful senior executive (who happened to be a body language aficionado) once told me he could evaluate his team's comfort by how high they held their coffee cups. It was his observation that the more insecure an individual felt, the higher she held her coffee. People with their hands held at waist level were more comfortable than those with hands chest high.

Most of all, remember that team members will be watching you all the time, and they will be waiting to see if your behavior is congruent in both formal and informal settings. When one CEO hosted a corporate function designed to gather ideas from participants, he listened attentively during the presentations, but spent the breaks sitting far away from the group, reading a newspaper. It was only natural shyness that caused him to withdraw, but by now I'm sure you can accurately guess how the other people in the group evaluated his behavior.

THE IMPORTANCE OF HOW YOU SAY WHAT YOU SAY

Joan got a call from her boss, Shelly. “I knew from the sound of her voice when she said hello and asked how I was that someone else got the promotion I was up for,” Joan told me. “I also knew that Shelly was unsure about her decision.”

How did Joan know those things from just the sound of a few neutral words?

Paralinguistic communication, also known as vocal body language, is the answer. Volume, pitch, inflection, pace, rhythm, rate, intensity, clarity, pauses—all of these play a role in how you say what you say—and that “how” can sometimes be more revealing of your true meaning than the “what” contained in the words.

Sued for the Sound of Your Voice?

In 2002, Nalini Ambady made audiotapes of physicians and their patients in session. Half of the doctors had been previously brought to court for malpractice. She played the tapes for her students, who were able to determine which physicians had been sued. But here's the catch: the recordings were “content-filtered.” All that the students could hear was a low-frequency garble. But based on the intonation alone, they could distinguish one group from the other. The doctors who had been sued had a dominant, hostile, less empathic style, whereas the other group sounded warmer.10

Leaders must therefore keep in mind that when they speak, their listeners won't only be evaluating their words; they will also be automatically “reading” their voices for clues to possible hidden agendas, concealed meanings, disguised emotions, unexpected surprises—anything, in short, that will help them determine whether or not they can rely on what they're being told. Your voice is as distinctive as your fingerprint. It conveys subtle but powerful clues into feelings and meanings. Think, for example, about how tone of voice can indicate sarcasm, concern, or confidence. Or how an increase in volume and intensity grabs attention because of the heightened emotion (passion, anger, assertiveness, certainty) it signals.

The limbic brain, where emotions are processed, also plays the primary role in processing vocal cues. Researchers from the University of Geneva in Switzerland discovered that they could tell whether a subject had just heard words spoken in anger, joy, relief, or sadness by observing the pattern of activity in the listener's brain.11

The effect of paralinguistic communication is so potent that it can, for example, make bad news actually sound palatable or, conversely, take all the joy out of a positive message. I've seen managers give unflattering feedback while still exhibiting warm feelings through their tone of voice—and those who were being critiqued still felt positively about the overall interaction. I've also seen managers offer words of praise and appreciation in such a flat tone of voice that none of the recipients felt genuinely acknowledged or appreciated.

In collaborative assignments, you are asking people to put aside their personal agendas and egos in the service of collective solutions that benefit the entire organization. For there to be any chance of this happening, team members have to know that the leader is 100 percent committed to their success. So when you say that you trust, support, and believe in your team, you'd better sound as though you mean it.

Speech Convergence

One of the most intriguing aspects of vocal behavior is speech convergence—the way people adopt the speech patterns and voice qualities of those whom they admire and want to be like. In fact, influence in an organization can be predicted by analyzing speech patterns. Those individuals who have the greatest effect on the greatest number of people (in terms of changing their speaking style) will also have the most control of the flow of information within the organization. So when you find the people in your organization who cause the most speech convergence, you also find the informal leadership.

Speech convergence can also be used as a technique to help people understand your message. The more adept you are at altering your speed, volume, and tone to match that of the group you are addressing, the better they will hear and accept what you have to say.

USING SPACE

Proximity is the measurable distance between two people. We keep different distances depending on the types of relationships we have with others. In North America, the intimate zone (0–18 inches) is reserved for those with whom we have close personal relationships—family and loved ones. The close personal zone (18 inches–2 feet) is the space that friends and trusted business colleagues can occupy. The far personal zone (2–4 feet) is the distance at which we feel most comfortable dealing with team members and business colleagues. The social zone (4–12 feet) is where the majority of our professional dealings take place and where we interact with new business acquaintances. The public zone (over 12 feet) is used mostly for public speaking. We unconsciously monitor these spatial zones, and we automatically adjust as we interact with various people and as a relationship evolves.

Reserved for loved ones and very close friends

Friends welcome

Team members invited

Where business relationships begin

Used for formal presentations

Broadly speaking, we tend to stand closer to those we like (or expect to like), who interest us, whom we trust, or whom we want to get to know. When you form a new team, people will initially interact in the social zone. However, as the group begins to gel—as they get to know and trust one another—you can see them move physically closer.

I always notice the amount of space my clients use with me. As they shorten the distance between us, I know that I am moving from being treated as a vendor to being seen as a trusted adviser.

When people are not aware of these zones and the meanings attached to them, unintentional violations can occur. For example, highly confident and powerful people typically occupy greater personal space, which may result in their infringing on another person's territory.

Space invasions are better tolerated when the invader is attractive or of high status. But people's territorial responses are primitive and powerful. When someone uninvited comes too close, it automatically triggers an increase in the heart rate and galvanic skin response (sweat gland activity and changes in the sympathetic nervous system) of the invadee. You can tell if you have infringed on people's space by the way they react—stepping away, withdrawing their head or neck, or angling their shoulders away from you.

Managers who stand over an employee who remains seated during a conversation risk causing the employee to feel subjugated or overpowered, creating a vague discomfort—however positive the actual words being said.

There are other kinds of territorial invasion as well. These include leaning on, touching, or standing close to another person's possessions—desk, computer equipment, furniture, and so on. Even leaning against a wall in someone's office or blocking a doorway can come across as dominating or intimidating.

It isn't only professional relationships that can suffer from unwanted space invasion. One night not long ago, when I was traveling on business, I had dinner at an oceanside resort, and I noticed a man and a woman seated across the room. The couple sat framed by a large picture window, while the setting sun turned the sky shades of yellow, orange, magenta, and deep purple. It was a beautiful image. But then I began to observe the couple's body language.

During the course of the meal, I watched the man lean toward the woman—and saw her respond by pulling away from him. He leaned toward her again—and again she pulled away. The more the man leaned forward, the more his dinner companion tilted back. By dessert, he was almost sprawled across the table, and she was practically falling backwards off her chair. I couldn't hear a word they were saying, but it was perfectly obvious that whatever he was proposing, she wasn't signing on.

The funny part was, the man seemed totally oblivious to the nonverbal signals the woman was so clearly sending. He would have been much more successful if he had (literally) backed off.

Seating Arrangements

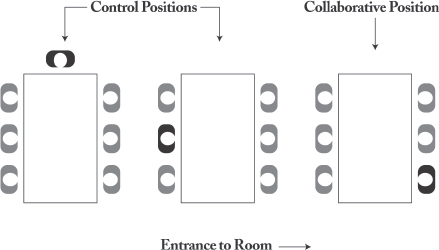

In most of the meetings you attend, the seating arrangement may not be an issue. But it can make a big difference in a collaborative session. I'm not suggesting that you use place cards for attendees, but you should be aware that strategic positioning is an effective way to obtain cooperation—and that neglecting this dynamic can inhibit your collaborative goals.

There are two power positions at any conference table—the dominant chair at the head of the table facing the door and the “visually central” seat in the middle of the row of chairs on the side of the table that faces the door. Choosing the dominant chair may be the most effective way for a leader to control the agenda or dominate the meeting, but it also stifles collaboration. When the leader takes this spot, ideas are then directed to him or her for validation (or rejection) rather than to the entire group. So take a moment before your next meeting and think about the relationship you want to establish with team members. Then choose your seat accordingly: sit at the head of the table or at the midpoint on the side if you want to exert control, and choose any other position around the table if you want to state symbolically that you are an equal member of a collaborative team.

Where you sit sends a message.

Seating positions may even help create leaders. For example, it's been noticed that people who sit at either end of the table in a jury room are more likely to be elected foreman and that persons in visually central positions (that midpoint previously mentioned) are also more likely to be perceived as leaders. In the jury scenario, choice of foreman is mainly about the symbolism of the head-of-the-table position; with the central position, it is more about the power of eye contact: because the person seated in this central location is able to maintain eye contact with the most group members, he or she will be able to interact with more people and, as a result, will most likely emerge as the leader. (So if you wanted to enhance the leadership credibility of a junior team member, it would be wise to seat him or her in one of these two positions.)

Have you ever noticed that when two people sit at a table, they often choose chairs on opposite sides? This is automatically adversarial in terms of territory—the kind of seating arrangement that divorce attorneys and their clients typically adopt. Groups of people may also sit on opposite sides of a conference table and unwittingly divide into an “us and them” mentality. If you intentionally mix up the seating arrangements (or hold your meeting at a round table—or forego the table and simply place chairs in a circle), you can discourage the tendency to “take sides.”

Sitting at right angles is the arrangement most conducive to informal conversation. Sitting side by side is the next best. This is important to remember if you want to foster personal ties between team members. The outcome of any collaborative effort is dependent on well-developed relationships among participants. People are naturally reluctant to share information with others when they don't know them well enough personally to evaluate their trustworthiness. So if you notice that the same people are taking the same seats at every meeting, rearrange the seating to stimulate conversation and encourage new relationships to develop.

Seating invites confrontation or collaboration.

If you want to accelerate collaboration after a merger, you might try something like what Sujit Patil of Tata Chemicals Limited describes here: “We experimented with a unique process during the integration meeting after one of our early M&As, where seating arrangement during employee integration made a positive difference. We arranged chairs in concentric circles, rather than in a theatre style or around a conference table that might have made one group seem dominant. This very subtle nonverbal communication was very powerful and ensured a feeling of equality among the managers from both the organizations. The participation level was much higher.”

Have a Seat—but Not There

“The Project Manager introduced a new consultant. The new guy smiled and shook hands with everybody, but it looked like an insincere, almost condescending smile and the handshake was soft and slippery. That was his first mistake. His next—and last—was sitting in the chair of a technical leader who was away on vacation. After that, the entire team boycotted the consultant, and his contract was quietly terminated after a couple of weeks. Nobody cared about his skills or contribution to the project.”

—E-mail from an engineer

DRESS FOR SUCCESS

The senior executive came in wearing a designer suit, white shirt, and power tie. He checked the time on his Rolex wristwatch and placed his elegant briefcase on the table. He exuded authority, power, and status, and would have been perfectly dressed for a board of directors function. But that wasn't the kind of meeting he was chairing.

He had assembled a multilevel, multifunctional group—a diagonal slice of thirty people from across the organization—and had taken them off-site for two days to cocreate the necessary steps for achieving the company's new strategic plan. The hope was that collaboration and knowledge sharing would begin at this meeting and expand from here into every department. It wouldn't be easy. The theme was “We're all in this together”—already a touchy subject, as the employees knew there would be cutbacks in spending and employee numbers. (And few expected that “together” meant that executives would also be asked to cut costs and reduce their ranks.)

But despite some initial reluctance on the part of the attendees, the first day had gotten off to a good start. Told to come dressed comfortably, most people were in jeans or slacks with polo or tee shirts. Consultants hired to facilitate the event had done a good job warming up the group and helping them begin to bond.

Then the senior exec came in to lead the meeting. From the moment he walked into the room, all hope for collaboration flew out the window. Not only was he making a late entrance (instead of arriving earlier that morning with the rest of the group), he didn't look like one of the team. He looked like a “suit,” a hierarchical leader who would ask for input only as a rubber stamp for decisions he'd already made.

I'll never know why he chose to dress like that. Maybe he had a business appointment with an important client later that day, maybe he thought that this was the way a senior executive should always dress, or maybe he just didn't think it mattered. But as anyone who was there that day could tell you, it not only mattered but was pivotal.

If I could have caught him before he entered the room, I would have told him to take off his jacket, loosen his tie, and roll up his shirtsleeves. (I'd also have advised him to remove the Rolex and leave the Gucci briefcase on a chair in the corridor.) But, instead, all I could do was sit there and watch as resistance and skepticism built and rippled through the assembled group.

I think of this incident every time I hear the words “dress for success.” As with every other piece of nonverbal communication, you need to first consider what “success” means in a particular context. Although there is absolutely nothing wrong with wearing an expensive suit and tie (in fact, it would be appropriate and advisable for almost any other executive function), you need to be aware of the message it sends. And ifyour goal is to support and model collaboration, then you need to realize that dressing like the other team members is the successful message in this situation.

WHAT YOUR OFFICE SAYS ABOUT YOU

Our brains are tuned to status. Michael Marmot, in his book The Status Syndrome, has shown that high status correlates with human longevity and health, even when income, education, and other environmental circumstances are factored in.12 In short, we are biologically programmed to care about status because it favors our survival.

Which brings me to your office.

Because you are a leader, you already have acknowledged status in your organization, but there are many ways your office can reinforce that status. You can occupy the largest (or the corner) room, have a picture window with a great view, or sit behind a massive desk (obstructing a visitor's view of your lower body). You can choose a chair with armrests, a high back that tilts, a swivel seat, and rollers for feet. You can then put the visitor in a smaller, lower, and fixed chair on the opposite side of your desk. You can even seat visitors on a low sofa across the room and place a coffee table in front of them. Arranging your office in this manner allows you to control the space between you and others, keeping them at a distance and in essence saying that you won't come to them—they must come to you (and only if invited).

Projecting power, authority, and status may be a key part of your nonverbal strategy to impress potential clients, customers, and investors—and I often advise clients to think of their office space as a symbol of their (and their company's) prestige.

But when it comes to building collaboration within your organization, status cues like these send a conflicting, distinctly unwanted message. If creating a collaborative culture is essential to meeting your business objectives, then you might want to rearrange your office to reflect this. For example, seating people directly across from your desk places them in an adversarial position. Instead, place the visitor's chair at the side of your desk, or create a conversation area (chairs of equal size set around a small table—or at right angles to each other) and send signals of informality, equality, and partnership.

FAMILIARITY BREEDS COLLABORATION

In the 1960s, the University of Michigan psychologist Robert Zajonc demonstrated an important, subconscious relationship that exists between familiarity and “liking.” Zajonc flashed up on a screen a sequence of irregularly shaped octagons, but ones too fleeting for the subjects watching to consciously register having seen them. He then showed those octagons again at a slower speed, together with a number of new ones, and asked his subjects to say which ones they “liked” best. Zajonc found that without exception they preferred the octagons they had been shown previously, even though they were unaware of having viewed them. He termed this phenomenon “the mere exposure effect.”13

What has this to do with leadership and collaboration? Plenty.

There are two kinds of knowledge in your organization: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge is information that can be transferred in a document or entered in a database. Accessing tacit knowledge (insights, intuitions, things that “we don't know we know”) requires a conversation and a relationship. The first building block of that relationship is “the mere exposure effect.” Familiarity increases the likelihood that your team members will like one another and feel comfortable enough to share their thoughts and speculations.

So when you hold off-site retreats, organization-wide celebrations, or workplace events, make sure to provide plenty of opportunities for social activities and to schedule frequent and long breaks. The more your team members see each other and interact in informal ways, the more they will like each other and build the personal bonds that later translate into collaborative success.

![]()

Today's corporation exists in an increasingly complex and ever-shifting ocean of change. Leaders therefore need to rely more than ever on the intelligence and resourcefulness of their staff. Collaboration is not a “nice to have” leadership philosophy. It is an essential ingredient for organizational survival and success based on the essential truth that none of us is smarter than all of us.