3

LEADING CHANGE

The Nonverbal Key to Effective Change Management

Last year I consulted with a company in the midst of major reorganization. I was hired to work with the executive team as they designed the change strategy and discussed ways to build employee engagement for the coming changes. At one of these planning sessions, a senior executive concurred that the restructuring would streamline and improve processes in her department. She seemed straightforward and fully supportive of the proposed changes. But at some point while I listened to her comments, it suddenly hit me: she didn't believe what she was saying. It was a combination of small things: her gestures came a beat too late, she made only minimal eye contact with the rest of the team, and her energy level was too low for someone who was supposed to be an enthusiastic supporter. She had done her best to be a good corporate soldier, but her body language revealed her true feelings. She didn't approve of the direction the company was taking.

I waited to see what would happen. Sure enough, a few weeks later, the executive resigned.

There is nothing that can invigorate a business like a major change. Maybe it's the adoption of a new strategic direction or the rollout of a new product line or the chance to acquire a competitor. But when leaders rally their troops to forge ahead, they often find they are leading a charge that employees (and even some other leaders) are unwilling or unready to embrace.

This chapter will show you how the brain is wired to reject change, and how emotions (yours and other people's) impact and influence an organization's ability to embrace change and transformation. And because most of the emotional content of a message is communicated nonverbally, you'll understand why body language expertise is crucial for anyone leading change. You'll learn to read the nonverbal signals of stress and resistance, how to use body language to be an effective speaker, and even how to “fake” charisma.

THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON CHANGE

Don't you just hate dealing with people who fight against every plan for organizational change? You know the type: they're disruptive, set in their ways, and highly resistant to change, even when it is obviously in the best interest of the business. Well, guess what? New research suggests that those troublemaking, inflexible change resistors are … all of us!

Recent advances in brain analysis technology allow researchers to track the energy of a thought moving through the brain in much the same way as they track blood flowing through the body. And as scientists watch different areas of the brain light up in response to specific thoughts, it becomes clear that we all react pretty much the same way to change: we try to avoid it.

Most of our daily activities, including many of our work habits, are repetitive tasks that take very little mental energy to perform. That's why “the way we've always done it” is so seductive. It not only seems right—it feels good. So it's no wonder that logic and common sense aren't enough to get people to sign up for the next corporate restructuring.

The Power of Emotion

Daniel Goleman's book The New Leaders starts with this statement: “Great leaders move us. They ignite our passion and inspire the best in us. When we try to explain why they are so effective, we speak of strategy, vision, or powerful ideas. But the reality is much more primal. Great leadership works through the emotions.”1

I once asked the CEO of a technology company how his employees were dealing with a proposed change.

“We've presented all the facts,” he replied. “But it would be much easier if people weren't so emotional!” In that organization, it seemed, employees were expected to analyze change and react rationally. Emotions were not supposed to be part of the equation.

It's an approach I've seen before: leaders quantifying everything they could to help employees reach objective conclusions. But, according to the neurologist and author Antonio Damasio, the center of our conscious thought (the prefrontal cortex) is so tightly connected to the emotion-generating amygdala that no one makes decisions based on pure logic. Damasio's research makes it clear that unconscious mental processes drive our decision making, and logical reasoning is really no more than a way to justify emotional choices.2 The more I study organizational transformation, the more I find evidence that emotion, not logic, is at the heart of successful change.

Ever wonder why it's so hard to promote a new change initiative when past changes have failed? The answer demonstrates the power of emotion over logic. When people are in a situation that requires them to make a decision, their brain searches for past situations that seem similar to the current one in order to access the emotions that are attached to them. In the case of a failed change, the negative emotion gets immediately accessed and transferred to the new initiative—regardless of the rationale for or validity of the current change.

Motivating Change

Leaders use two sets of emotions to motivate change: negative and positive. In “crisis motivation” and “burning platform” rationales, the basic idea is to frighten employees into accepting change. And there is no doubt that negative emotions can be effective. Fear, anger, and disgust all trigger physiological responses that prepare the body for quick and specific actions.

But far more frequently, organizational change is neither quick nor specific. Rather, it is continuous, evolutionary, and often strangely ambiguous in nature, which means that managing such change requires much more innovative and flexible approaches. For this kind of change, negative emotions aren't much help at all. In fact, negativity significantly diminishes problem-solving abilities and narrows rather than expands creative thinking. That's why today's most effective change agents focus primarily on positive emotions that motivate people to commit to change and to act on that commitment.

Emotional Contagion

A business simulation experiment at Yale University gave two groups of people the assignment of deciding how much of a bonus to give each employee from a set fund of money. Each person in the group was to get as large a bonus as possible for certain employees, while being fair to the entire employee population. In one group, the conflicting agendas led to stress and tension, whereas in the second group, everyone ended up feeling good about the result. The difference in emotional response was created by the “plants”—actors who had been secretly assigned to manipulate people's feelings about the project. In the first group, the actor was negative and downbeat; in the second, positive and upbeat. The emotional tone of the meetings followed the lead of each actor—although none of the group members understood how or why those particular feelings had emerged.3

Emotional contagion is primarily a nonverbal process. When one team member is angry or depressed, negative body language can spread like a virus to the rest of the team, affecting attitudes and lowering energy. Conversely, happy and buoyant people are likely to make the entire team feel upbeat and energized. Reviewing research on the emotional contagion phenomenon, neurologist Richard Restak concluded, “Emotions are infectious … you can catch the mood of other people just by sitting in the same room with them.”4

It's also true that emotional leads tend to flow from the most powerful person in a group to the others. During a major change, people will be on high alert, constantly looking to their leader for emotional cues. If you stay relaxed and optimistic, members of your work groups will be more positive and more productive. If you become upset, depressed, or angry, those emotions will be “caught” by your team and expressed in a variety of less-than-optimal results, including higher absenteeism and lower productivity.

THE BODY-MIND CONNECTION

As you know, when you're happy, you smile. But did you know that when you smile, you feel happier? Called “facial feedback,” the effect is so powerful that even when you artificially produce a smile, the feedback from that facial expression affects your emotions and behavior. In one research project, participants were either prevented from smiling or encouraged to smile by holding a pencil in their mouths. Those who held a pencil in their teeth and thus were “forced” to smile rated cartoons as funnier than did those who held the pencil in their lips and could not smile.5

In another study, the University of California School of Medicine found that simply moving the facial muscles in the direction of fear, anger, disgust, sadness, happiness, and so on caused autonomic nervous system reactors—heart rate, blood pressure, skin temperature—to move in the direction of the respective emotion.6

And it isn't just facial expressions that have an impact on your nervous system and emotions. Your physical postures and movements are also involved. Take, for example, research at Radboud University, the Netherlands, that showed how backward motion was a powerful way to enhance cognitive control. The researchers found that when people encounter a difficult situation, getting them to step back (literally) boosted their ability to cope.7

Can You Fake Charisma?

Charisma has been described as personal magnetism or charm. Charismatic people are more outgoing, but they also spend more face-to-face time with others—picking up cues and drawing people out. It's not just what these leaders project that makes them charismatic; it's how they make others feel about themselves. Good leaders make employees believe in them. Great leaders make employees believe in themselves. It's all about dealing compassionately and effectively with people: listening, empathizing, and encouraging others to achieve outstanding results. So learning to read and respond to body language signals is crucial to leadership charisma.

But, of course, charisma is also about an individual's infectious positive attitude, personal energy, and enthusiasm, as projected through his or her body language. Nonverbal gestures are the most charismatic when they are organic and not affected, when they naturally enhance the verbal message. And as an executive coach, I help clients develop this aspect of charisma by teaching them to align their verbal (logical) and nonverbal (emotional) communication so closely that they are perceived as more poised, persuasive, and influential.

Faking charisma takes a little practice—because, again, you're dealing with emotions. Trying to display confidence when you're actually feeling uncertain, or to be seen as upbeat and positive when (for any reason) you are feeling the opposite, is a tricky thing. But there are two valid options that will work: you can use a Method acting technique (I elaborate on this further in the next section), or you can work at the somatic level by understanding the body-mind connection.

According to research from Harvard Business School, subjects who held their bodies in certain physical poses changed their neuroendocrine levels, their emotions, and their behavior.8 Here are findings from the study:

- Subjects holding their bodies in expansive, “high-power” poses (putting their hands behind their heads and their feet on the desk, or leaning over a desk and planting their hands far apart) for as little as two minutes stimulated higher levels of testosterone (the hormone linked to power and dominance) and lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

- In addition to causing hormonal shifts, power poses led to increased feelings of power and a greater tolerance for risk.

- People often are more influenced by how they feel about you than by what you're saying.

Learning body language skills isn't just helpful for communicating effectively to an audience; it also trains you to adopt positive, powerful, and uplifting postures and movements that in turn affect your mental state. As you assume the posture, gestures, expressions, and stance of confidence and charisma, you actually become more charismatic.

Emotional Memory—“the Method”

During the late 1800s, a new approach to acting was developed by a Russian actor, director, and coach, Constantin Stanislavsky. Called Method acting (or more simply, the Method), it was adopted by a new school of realistic actors including Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, and Robert DeNiro. The Method held that an actor's main responsibility was to be believed; and to reach this level of “believable truth,” Stanislavsky employed methods such as “emotional memory,” which drew on real but past emotions. For example, to prepare for a role that involves fear, an actor would remember something that had frightened him or her in the past, and bring that memory into the current role to make it emotionally valid.

As a leader, you will have different goals than an actor in a play, but the sense of conviction and believability you want to project will be fundamentally the same. For example, if you were going to announce an organizational change at an upcoming meeting and you wanted to exude confidence, here is how you'd go about it:

- Think of an occasion when you were enthused, confident, and absolutely certain about a course of action. (This doesn't have to be taken from your professional life. What's important is identifying the right set of emotions.)

- Picture that past event clearly in your mind. Recall the feeling of certainty, of enthusiasm, of clarity of purpose—and remember or imagine how you looked and sounded as you embodied that state of mind.

- Picture yourself at the upcoming meeting with the same positive attitude and sense of confidence that you had in the past. The more you repeat this mental rehearsal—seeing yourself at the upcoming meeting assured, confident, and certain—the more you increase your ability to make the change announcement with body language that is triggered by that authentic, positive emotion.

Is Acting in Your Blood?

Nicholas Hall, a psychoneuroimmunologist and researcher, studied professional actors who portrayed contrasting personality types in a one-act play. He took blood samples before and after each performance and found that people who had been working with happy and uplifting scripts all day had healthy immune systems. Those people who had been working with depressing scripts all day showed a marked decrease in immune responsiveness.9

But whatever you do, don't try to simply suppress an emotion and think you are fooling anyone. Trying to suppress genuine emotions requires a great deal of conscious effort and is rarely successful. Whenever you try to conceal any strong feeling, your body “leaks” nonverbal cues that are picked up consciously or subconsciously by your audience.

The Problem with Suppression

Stanford University's research on emotional suppression shows why it's so difficult to hide our true feelings: the effort required takes a physical and psychological toll. Subjects instructed to conceal their emotions reported feeling ill at ease, distracted, and preoccupied. This was validated by a steady rise in their blood pressure. But another quite unexpected and, for our purposes, much more important finding showed a corresponding blood pressure rise in those listening to the subjects. The tension of suppression wasn't just palpable; it was contagious.10

ANNOUNCING CHANGE

The higher you advance in an organization, the more frequently you will be expected to give formal presentations. And nowhere will your speech-making talents be put more rigorously to the test then when you are announcing a major change.

Because of the personal and emotional nature of change, the audience will be monitoring your every move, and their brains are primed by evolution to look first for possible threats. A little nervousness at the beginning of the presentation will not be overlooked. Instead, it will be magnified and (most likely) interpreted negatively.

My best advice is never to promote a change you don't believe in—and always be as transparent and candid as possible. Doing so will help your body align authentically to reflect that openness. Even then you will need to pay close attention to your nonverbal signals. If you slouch, look down, clasp your hands in front of you, sway back and forth, or sound tentative, these behaviors (even if they are only nervous habits) can come across as uncertainty—or worse.

Body Language Onstage

Coaching executives in presentation skills, I know the importance of a well-written speech with an inspiring vision, engaging stories, self-deprecating humor, and personalized examples. But I also know that leaders can sabotage a great speech if they underestimate or ignore the power of body language.

I don't want you to make that mistake. Here are eight of the most important elements of body language onstage.

1. Manage Your Stress Level While you are waiting backstage, notice the tension in your body. Realize that some nervous energy is a good thing—it's what makes your presentation lively and interesting—but too much stress results in nonverbal behaviors that work against you.

Before you go onstage, stand or sit with your weight “centered”—evenly distributed on both feet or your “sit bones.” Look straight ahead with your chin level to the floor and relax your throat. Take several deep “belly” breaths. Count slowly to six as you inhale and increase the tension in your body by making fists and tensing the muscles in your arms, torso, and legs. As you exhale, allow your hands, arms, and body to release and relax. Further loosen up by gently shaking one arm and then the other, and let your voice relax into its optimal pitch (a technique I learned from a speech therapist) by keeping your lips together and making the sounds “um hum, um hum, um hum.”

2. Focus on Your Message—All of It Successful change communication involves several levels of information: the audience needs to understand the rationale for change (the marketplace realities that are behind the reason for change); they need to agree with the urgency for change (the conditions, challenges, and opportunities that make it imperative that the change happen now); and they need to believe they have the skills (or access to the skills) that are necessary to achieve the change. But you've seen why those factual components alone are not enough to compel people to action.

In order for people to be motivated to act, they need to be emotionally involved. So before you go onstage to deliver your message, concentrate on emotions and feelings. How do you personally emotionally connect with the proposed change? What do you feel about it? How do you want the audience to feel? What do you need to do nonverbally to embody those feelings?

3. Make a Confident Entrance Staying relaxed, walk out onstage with good posture, head held high, and a steady, smooth gait. When you arrive at center stage, stop, smile, raise your eyebrows, and slightly widen your eyes while you look around the room. A relaxed, open face and body tell your audience that you're confident and comfortable with the information you're delivering. Because audience members will be mirroring any tension you display, your state of comfort will also relax and reassure them. (This may sound like common sense, but I once worked with a manager who walked onstage with hunched shoulders, a furrowed brow, and squinted eyes. I watched the audience squirm in response. It was an unsettling way to begin a “Let's get together and support this change” speech.)

4. Maintain Eye Contact Maintain steady eye contact with the audience throughout the talk. If you don't, you will quickly signal that you don't want to be there, that you aren't really committed to your message, or that you have something to hide.

Although it is physically impossible to maintain eye contact with the entire audience all the time, you can look at specific individuals or small groups, hold their attention briefly, and then move to another group or individual in another part of the room.

5. Ditch the Lectern Get out from behind the lectern. A lectern not only covers up the majority of your body but also acts as a barrier between you and the audience. Practice the presentation so well that you don't need to read from a script. If you use notes, request a video prompter (or two) at the foot of the stage.

6. Talk with Your Hands Speakers use hand gestures to underscore what's important and to express feelings, needs, and convictions. When people are passionate about what they are saying, their gestures become more animated. That's why gestures are so critical and why getting them right in a presentation connects so powerfully with an audience. If you don't use them (if you let your hands hang limply to your sides or you clasp them in the classic “fig leaf” position), it suggests that you don't recognize the crucial issues, have no emotional investment in the issues, or are an ineffective communicator.

There are three categories of gestures—emblems, pacifiers, and illustrators. Emblematic gestures have an agreed-on meaning to a group and can be understood without words. (The finger-to-lips “be quiet” gesture is one example.) Pacifiers are gestures that people use to relieve stress. (More about these later in the chapter.) Illustrative hand gestures develop simultaneously with speech. They are so tightly linked with speech that we rarely communicate without them. Illustrators help us find the right words and make the expression of thoughts more emphatic and precise. Even blind people use illustrators when speaking—just as all of us gesture when talking on the telephone.

Authentic illustrators occur split seconds before the words that accompany them. They either will precede the word or will be coincident with the word, but will never come after the word. (This is one reason why trying to choreograph gestures in advance when preparing a presentation seldom works. The timing is off.)

If I were working with you before an important presentation, my advice would be to focus on the importance of your message and the emotions behind it, and let your natural ability to illustrate take over automatically as you speak—just as it does when you are chatting with friends.

But if you feel that your gestures do need a bit of rehearsing, let me remind you of a few basic guidelines:

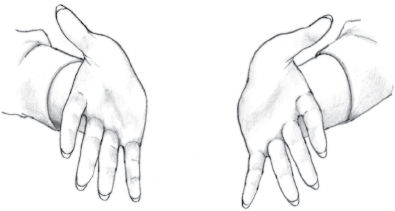

- Palms facing straight up communicate the lack of something that the speaker needs or is requesting.

He needs something.

- Gestures with palms showing (tilted to a forty-five-degree angle) signal candor and openness.

She's open and candid.

- Palm-down gestures signal power and certainty.

He's made up his mind.

- Vertical palm gestures with a rigid hand are often used to beat out a rhythm that gives emphasis to certain words.

She's adding emphasis.

- Steepling signals confidence and expertise about the point you are making.

- Arms held at waist height, and gestures within that horizontal plane, help you (and the audience) feel centered and composed.

- Open arms signal inclusion.

- Hands touching the face, head, or hair make you look nervous or tentative—as does the “fig leaf” gesture in which hands are grasped together in front of the groin area.

- Hidden hands make you look less trustworthy.

- Gestures above your shoulders come across as erratic and overly emotional.

7. Move Human beings (males, most especially) are drawn to movement. Movement keeps an audience from becoming bored. It can be very effective to move toward the audience before making an important point, and away when you want to signal a break or a change of subject. But don't move when you are making a key point. Instead, stop, widen your stance, and deliver the message.

8. Monitor the Audience Keep reading the audience. Are they engaged or bored? If you see their interest flagging (increased texting, glancing at watches, and so on) do something unexpected: pause abruptly, change your voice level or tempo, ask a question, or involve the audience in an exercise.

One Small Nod

I've seen this with hundreds of audiences: when people connect with a message, they respond with a single nod. It's unconscious, and it's universal. See for yourself. When you are speaking, it's easy to tell if you've really connected. Watch for that one small nod.

Of course, the most important response to monitor is the audience's emotional reaction to your message. If you are announcing a large-scale organizational change, prepare to see a wide range of body language. And expect much of it, at least initially, to be negative.

Freeze, Flight, Fight

Change jerks us out of our comfort zones, activating the amygdala, which heightens the emotions of fear and anxiety and triggers the body's “freeze, flight, or fight” response. Signs of the amygdala's influence show up almost immediately after a major change is announced, and if you watch carefully, you will see people's body language reflect these responses.

Freezing is the body's first line of defense against threat or danger. And in organizational transformation there are obvious threats: people are afraid of the unknown, afraid of failure, afraid of appearing to be or actually being inadequate to face the new challenges. There is also the very real potential for loss—of current workplace relationships, the value of current competencies, the current rate of compensation, and (in some cases) even employment. No wonder so many people's first inclination is to freeze in place when hearing about the next restructuring.

The threat inherent in change also causes people to respond by becoming as inconspicuous as possible. They will breathe shallowly (or even hold their breath); withdraw their jaws by tucking their chins; raise their shoulders toward the ears, causing the neck to look shorter (the opposite of “sticking one's neck out”); avoid eye contact; draw their arms close to their bodies; and minimize hand gestures. I've even seen people literally sink lower in their chairs in order to avoid detection.

Preparing for flight is the body's second option for action. Here the urge is to get far away from the situation. This can be reflected in a variety of distancing and disengagement behaviors. People may turn away, lean away, use objects as barriers, cross their arms and legs, or point their feet toward the nearest exit. You will also notice an increase in eye blocks—people rubbing or closing their eyes. Eye-blocking behaviors are so hardwired that children who are born blind will cover their eyes when they hear things they don't like.

Except for those who choose to resign, actual flight is not a viable option (most people can't dash out of a meeting room), and to compensate, people will increase pacifying behaviors in order to sooth or calm themselves. Pacifiers are used on a daily basis, but with limbic system arousal, they greatly accelerate. Expect to see people exhibit more self-touching—hand wringing, hair twirling, leg rubbing, temple massaging, lip touching, and so on.

Neck touching is one pacifier that differs between men and women. Women will lightly touch the side of their neck, cover the notch at the base of the neck, or play with a necklace. Men will more robustly grasp the front of the throat near the Adam's apple.

Fight (or active resistance) is the body's final tactic. Teeth clench, jaws jut out, eyes narrow, faces turn red, and hands curl into fists. Displays of aggressive body language include puffing out the chest and violating another person's space. Anger about to turn into rage is indicated by nose wings that start to dilate as the person oxygenates before going into action.

And You Thought Board Meetings Were Dull

One CEO wrote in another executive's performance review that he didn't appreciate the man's “negative body language,” and threatened to fire him if he didn't stop pretending to shoot himself in the mouth with his finger every time the CEO proposed an initiative.

WHAT DO PEOPLE WANT FROM YOU?

Let's play a game. Here are the rules: we'll be asked to split a sum of money. I get to make the split, and you get to choose whether to accept or reject the split. If you reject it, both of us will walk away empty-handed.

Rationally, I should realize my advantage and offer a lopsided split in my favor, and you should accept the uneven split—because any amount of money is better than nothing. Right?

Wrong. If we're like everyone else who plays the game, we'll end up with an even split. Although the fairness of the split shouldn't logically affect the second player's decision, it nearly always does. If offered a lopsided split, the second player will reject the deal, and neither player will get any money.

To find out why people react in this way, a team of Princeton researchers attached players to fMRI machines. They discovered that when people are offered an unfair split, a primal part of their brains known as the anterior insula sends out signals of disgust and anger.11 It doesn't matter one little bit that rejecting the split—regardless of how unfair—is an irrational financial decision. It feels right.

A close look at the psychology of relationships reveals that most individuals automatically attempt to keep a mental balance between what they contribute to a relationship and what they get back from it. When employees believe that they are putting more into their company than they are getting back, or when they do not perceive the distribution of rewards to be equitable, engagement slips dramatically.

When employees look for balance through equitable treatment, it is their perception of the treatment, rather than the treatment itself, that defines reality. And this perception is often created by what I refer to as the “symbolic behaviors” of leaders. The CEO of a chemical manufacturing company put it this way: “As a leader you must make it a routine part of your decision-making process to ask the question: Will this action be perceived as equitable?”

Your every action counts—so if you typically eat lunch with other executives in a special dining area, park your car in a reserved space, and don't rein in your own spending when asking lower-level employees to make cost cuts, the inequity symbolized by your behavior can demotivate the workforce and derail a major change initiative.

THE POWER OF EMPATHY

A few years ago, I conducted a research project for a regional president who had recently taken on his new position. “I am replacing a man who had been with the company for twenty years,” he said. “I'm new to the organization, and I'd like you to find out what employees need from me as their leader.”

A week later, I gave him my report. “I think you're going to like what I found,” I began, “because what employees need most won't cost you anything. People aren't asking for additional pay or more support from headquarters. What they are waiting for—and what they want from you more than anything else—is a validation of their emotions and your acknowledgment of their distress.” The employees in his division were waiting for the new leader to say to them, “You've lost a leader who was your friend, mentor, and model. What a difficult time you must be having! I can only imagine how tough this is on you.”

Empathy is a powerful tool during transitions. People are more likely to hang on to the fear, uncertainty, and other negative emotions that major change brings if it seems to them that management has no clue about what they are feeling. Your team members don't expect you to solve all their problems and address all their concerns. But when people react emotionally to change, they want your respect, empathy, and understanding—which is why it is imperative that you identify and respond to their nonverbal cues.

It's only after a person's negative emotional reaction has been validated and allowed expression that he or she can begin to focus on the potential benefits and opportunities that are also inherent in any change. It is only after being allowed to mourn and honor the past that people can release it and begin to look to the future. And at that point, people need leaders who model optimism and a positive attitude—and, by doing so, inspire others to take action and to believe that they can and will succeed.