8

INTERNATIONAL BODY LANGUAGE

Input from Twelve Experts

I have worked (given speeches or seminars, coached or consulted) in twenty-four countries, and I have traveled to a dozen more. But I certainly don't consider myself an expert on international business practices. I do, however, have access to a network of businesspeople who are experts—professionals and communicators from around the world, many of whom are affiliated with the International Association of Business Communicators (IABC). This chapter is a compilation of their insights and experiences with global body language and business protocol. In this chapter, you'll get a multicultural perspective of how eye contact, touch, space, emotional expression, and greeting behaviors are exhibited in a business meeting; you'll increase your ability to understand and identify cultural differences; and you'll be able to anticipate more accurately how your behavior is likely to be perceived.

I'd like to introduce my panel of experts….

Marc Wright (United Kingdom) is the publisher of www.simply-communicate.com, the online resource and magazine used by fifteen thousand internal communication professionals around the world. Marc is chair of IABC Europe & Middle East; chair of simplyexperience, an event and video production company; and chair of simplygoodadvice, a consultancy specializing in internal communication.

Paulo Soares (Brazil) is a professional with broad experience in business communication. He currently works as corporate communications general manager of Vale (a multinational mining company), responsible for the communication in Brazil. He also serves on the IABC international board and is a member of the ABERJE (the Brazilian association of business communication).

Helen Wang (China) is originally from China, but has lived in the United States for over twenty years. After receiving her master's degree from Stanford University, Helen worked in a think tank and consulted for Fortune 500 companies. Helen is also an entrepreneur in Silicon Valley and has worked extensively with business communities in China. Author of The Chinese Dream: The Rise of the World's Largest Middle Class, Helen advises and consults for companies doing business in China.

Judette Coward-Puglisi (Trinidad and Tobago) is the managing director of Mango Media Caribbean, a strategic communications firm serving global clients. Judette is a former award-winning documentary producer and journalist and the founding president of IABC Trinidad and Tobago.

Jennifer Frahm (Australia) is the director of her own change management and communication consultancy, Jennifer Frahm Collaborations, in Melbourne. She is the founder of Conversations of Change, an off-site retreat for people wanting to make change in their businesses and careers. She is the current chapter president of IABC Victoria, Australia.

Roberto Islas (Mexico) is the director of international private banking for HSBC Private Bank (UK) Ltd. A native Mexican, Roberto has an extensive knowledge of the Latin American markets.

Silvia Cambié (Germany) speaks five languages and has spent her entire career in an international environment. She is a business communicator and journalist, currently based in London, where she runs Chanda Communications and advises clients on strategic communication, stakeholder relations, and social media. Silvia serves as a director on the executive board of IABC and is the coauthor of International Communications Strategy: Developments in Cross-Cultural Communication, PR and Social Media.

Priya Sarma (United Arab Emirates) has worked with the leading advertising agencies in both India and Egypt. Currently she is the corporate communication manager for Unilever, leading the function across North Africa Middle East as well as Central Africa. She is based in Dubai.

Kazuhiro Amemiya (Japan) worked as a corporate communication manager and a webmaster at Texas Instruments Japan and Intel Japan, before establishing Crossmedia Communications, Inc. Kaz has helped communication managers and webmasters strategize their online communication ever since. He is a member of IABC and the Public Relations Society of Japan.

Sujit Patil (India) has close to fourteen years of experience across all the facets of business communication—marketing communications, branding, PR, crisis communications, and internal communications. He leads a comprehensive communications function at Tata Chemicals Ltd., a leading chemicals company with manufacturing operations across Asia, Europe, Africa, and the United States. He won the 2010 IABC Gold Quill Excellence award for employee communications.

Saada Ibrahim Mufuruki (Tanzania) is the managing director of M&M Communications Ltd., one of the leading communications agencies in Tanzania. Saada started her communications career with Ogilvy & Mather and later joined ScanAd Kenya. In 1992, she was appointed CEO of ScanAd Tanzania. Saada is the vice chair of the Advertising Practitioners Association of Tanzania and is the Tanzania chapter president of IABC.

Laine Santana (the Philippines) is the senior corporate communications manager for HSBC Asia-Pacific, covering news management and investor relations messaging for the region. She set up the public affairs department in HSBC, and as vice president was instrumental in building the bank's profile and reputation as it expanded its business in the Philippines.

I asked each of the panelists to help me coach a (fictitious) senior manager from the United States in the nonverbal and cross-cultural aspects of attending a business meeting in his or her respective country. Here are the eight questions I asked:

- How do you greet business partners?

- How do you exchange business cards?

- What does it mean to be “on time” for a meeting?

- How close do you stand in a conversation with a business colleague, and how often do you touch?

- What amount of eye contact is appropriate between businesspeople?

- If the meeting were around a conference table, where would your most senior executive sit, and where would the American executive be seated?

- What is the role of emotion in business dealings?

- Would any of this advice be different if the U.S. executive were a woman?

GREETING BEHAVIORS

The handshake is fast becoming a universal business greeting, but there are still some very interesting cultural variations. The Japanese give a light handshake. Germans offer a firmer shake with one pump, and the French grip is light with a quick pump. Middle Eastern people will continue shaking your hand throughout the greeting. And don't be surprised if you are occasionally met with a kiss, a hug, or a bow somewhere along the way. Here is what the panelists said:

Marc (UK): When shaking hands, dominant males will try to angle their wrist to make their hand uppermost. Women often drop their gaze during a handshake and will tend to disengage first. Kissing is becoming more in evidence, but more prevalent between women. Men will only kiss a woman if they know them well. Men very rarely hug each other—and never ever kiss each other.

Paulo (Brazil): It will depend on how formal the business is and if you have met the people before. Shaking hands is the most common, but one or two kisses (depending on what region of Brazil you are in) can happen between male and female. Hugs will happen if you have any intimacy with your business partners. That can happen between males, females (more common), and also males and females.

Jennifer (Australia): In Australia, it is customary and appropriate to greet with a firm handshake whether you are male or female. If you are a female and you receive a soft or limp handshake from a male, it usually signifies a male executive who has not come to terms with women in the workplace and thinks that you may need “special” treatment.

Roberto (Mexico): In Mexico, you greet mainly with a handshake if it's the first time you meet the prospect-client-partner. Thereafter it is not uncommon to kiss once (the ladies) and hug the men. Latin Americans are kind of expected to do this, after two or three meetings; people from Anglo countries tend to take longer to hug, and this is understood. If it is a well-known business partner, you would always kiss (ladies) or hug (men).

Silvia (Germany): Germany has a very formal business culture. Shaking hands is the expected greeting. And it is very important that your grip is firm and “determined.” People will evaluate you from it. A kiss on the cheek is rare, but maybe a bit more common in southern Germany, or between businesswomen (or former colleagues) if they know each other well.

Priya (UAE): Locals greet each other with a hug and three kisses on the cheeks. This holds for both men and women. In Arabia (Gulf and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [KSA]), between men the traditional greeting is one rub of the nose. When local men greet local women, they both bow slightly at the waist and put their hand on the left side of their chest (over the heart). However, with an increasingly large number of expatriates in the Middle East, when locals meet foreigners or expatriates, they shake hands. In KSA, though, men and women (even when meeting expats) never shake hands.

Kaz (Japan): If both parties are Japanese, people make a light bow, even if one person works at a foreign-affiliated company or deals with foreigners on a daily basis. When we greet a foreigner, we usually shake hands. Kissing or hugging hardly ever, if not never, occurs among Japanese in a business setting, but those styles of greeting appear to be more acceptable if the other person is a foreigner and both have known each other very well.

Sujit (India): A confident handshake is a preferred first contact. The “duration” of the handshake is a tricky situation. A major discomfort is a handshake that lasts the entire introduction! For me, a quick, firm, warm, and nondomineering yet engaging handshake works the best. The vibes should be good and accompanied by an empathetic smile rather than a cocky, materialist one. Although men rarely hug on the first meeting, for associates who have been in contact for long but have never met before, side hugs work well in demonstrating affection, warmth, and the fact that the person was looking forward to the meeting.

Saada (Tanzania): It depends on the situation as follows. In business meetings, if it is man-to-man or woman-to-man, it would be a handshake. The males normally continue the handshake long after the greetings. The handshake is normally strong between the men. Depending on the seniority, age, or position, the junior person would have his left hand holding his or her wrist during the handshake as a sign of respect. (One note: If it is a greeting among staunch Muslims, a man will not shake hands with or kiss a woman if she is not his sister, mother, grandma, or aunt. Greeting is purely verbal.)

If the greeting is between ladies and they know each other, then it would be a kiss on both cheeks with no handshakes. If they are meeting for the first time or have met just a couple of times, they will just shake hands.

Laine (Philippines): In the Philippines, a firm handshake is still the most appropriate for both men and women. Eye contact is important to establish rapport and focus, and a smile is a plus that will surely put both parties at ease. For colleagues (men with women or women with women) who have known each other for some time, it is becoming common to greet each other with a kiss. Here it's a one-cheek (air) kiss. Sometimes it doesn't happen upon introduction, but after warming up with a first meeting, they say good-bye with a buss. For men, a handshake at the start and end of a meeting will suffice.

BUSINESS CARDS

In the United States, we are very casual with business cards—handing them out as a poker player might deal a deck of playing cards. As you can see from the panelists' comments, other cultures have different (and sometimes ritualistic) ways of exchanging business cards.

Marc (UK): Many Brits don't have or use them, as we expect people to trust us—“our word is our bond.” When people hand out business cards, there is usually a flurry with a pen as they adjust their latest title, e-mail address, or mobile number with the phrase, “I've been meaning to update these for ages.”

Paulo (Brazil): After exchanging the cards, we usually put them on the table where we have the meeting in order to keep the people's names in mind.

Helen (China): The Chinese hand out business cards with both hands. Sometimes they even bow a little while holding the business cards above their heads to show respect. When you receive someone else's business card, always look at it and acknowledge it. When you put it away, place it carefully in your card case or with your business documents.

Judette (Trinidad and Tobago): In a formal meeting, we wait for the senior person to take out his or her business card. We tend to be polite and show interest by actually looking at the card.

Jennifer (Australia): The giving and receiving of business cards is reserved for relationships that matter in Australia. We view those who hand out business cards indiscriminately as not to be trusted and probably trying to sell something. If you are told, “Oh, I don't have my new card; they are still at the printers,” you may have made the Australian nervous, and he or she is planning an immediate exit.

Roberto (Mexico): Usually you give them out with the handshake. People look at them, and if it's a formal meeting, you keep them on the top of the table. If it is in a restaurant, you put them in your pocket.

Silvia (Germany): Business cards hold a great importance—especially at the beginning of a meeting. Germans will check it to see your title and level within your company. At one meeting, an Italian executive didn't have a business card (which is quite common in that culture), and my German colleagues couldn't believe it.

Priya (UAE): They are handed out formally at the start of the meeting as a form of introduction. There is no ceremony or process to their handing out.

Kaz (Japan): Exchanging business cards is considered the most important part of greeting. (Freshmen even learn the appropriate way—like a ritual.) It has to be very polite. We are expected to give and receive business cards with both hands and with a light bow. Be sure to present your card so that the other person does not have to turn it over to read your information.

Sujit (India): Like most Indians, I would take it as an insult if someone just took my card and put it in his pocket without even reading it! On a very formal first meeting, many professionals use both hands while giving and receiving the cards and also reflexively bow a bit. Designations and hierarchies matter in corporate India, and it is always good to take a few seconds to read the card and maybe acknowledge it before you stack them in the purse or a pocket. I always appreciate a person who writes down on the back of my card the context, reference, date of meeting, and so on. The nonverbal communication I get in this action is that he or she is interested in getting back in contact.

Saada (Tanzania): Mostly the card is passed around the table, or one goes round the table and hands out a card to each person.

Laine (Philippines): In the Philippines, we usually present the card with both hands to the recipient. The receiver will acknowledge with thanks and a nod and take some time to look at the card details before keeping it or laying it on the table for easy reference, especially if meeting a number of people.

TIME

Whether time is perceived as a commodity or a constant determines the meaning and value of being “on time.” Misunderstandings can occur when one culture views arriving late for a meeting as bad planning or a sign of disrespect, while another culture views an insistence on timeliness as childish impatience. If a meeting is scheduled to start at 2 P.M. and end at 4 P.M., when would you show up? And when would you expect to be finished? Simple questions, but with culturally determined answers.

Marc (UK): Up to 2:08 start time is acceptable; 2:15 is considered rude. Could overrun to 4:15. Attendees will mostly be attentive, but it is acceptable to be suddenly called out. Around half will have laptops open. All will do BlackBerry checks from time to time. Everyone stops for tea, which has a quasi religious dimension in UK meetings. Quality of biscuits (cookies) will be remarked upon.

Paulo (Brazil): Brazilians are not very “on time” for their meetings and events. Up to thirty minutes late is okay, and meetings usually are not scheduled to finish on time. There is a time for them to start, but never to finish.

Helen (China): Some Chinese do not take it seriously to be on time for a meeting, although this is changing. The Chinese tend to have spontaneous meetings. It is very hard to schedule a meeting ahead of time. They do not keep a calendar. Once, I tried to schedule a meeting with a Chinese colleague two days prior; he said, “Call me the day you want to meet, and we can make an arrangement.” It's acceptable that people show up to meetings fifteen to twenty minutes late.

Judette (Trinidad and Tobago): Assume the meeting will begin at 2 P.M. and be there for 2; be prepared to indulge in light chatting about sports, social events on the national calendar, and so on before diving into the meeting. Assume the meeting won't end at 4 P.M. and leave yourself some flexibility.

Jennifer (Australia): The meeting should start at 2 P.M., and anything later than ten minutes past is considered bad manners. Likewise we expect the meeting to finish on time. In corporate environments, the day is dominated by meetings, so when one runs late, so do the others. The exception is the Very Important Person, who will communicate his or her importance by running late from other Very Important Meetings.

Roberto (Mexico): This is a very complex issue. In Mexico, people are almost always “fashionably late” (up to half an hour). If you are meeting a client, you are expected to be on time; the client can always be late, and it is not uncommon. Also, it is rare to put “end times” to meetings; they usually go until finished. As they usually start late, putting an end time would not work, and may actually be seen as pressure, which is negative.

Silvia (Germany): It is very important to be punctual—and to keep the agenda, coffee breaks, and so on, on time. So if we say the meeting is 2 to 4 P.M., people will arrive at 1:50 and expect to leave promptly at 4. If you don't adhere to a strict schedule and if you don't end as scheduled (or at least have an apology and a logical explanation for why you aren't doing so), you will be judged as “sloppy,” and your professionalism will be questioned.

For a business meeting, you need to show that you are prepared. You must have a written agenda. Everything needs to be itemized—and distributed in advance, if possible. The person chairing the meeting will introduce everyone (name, title, position in company), and either explain why each person is attending or ask the individuals to do so.

In German there is a word (Nachbereitung) that roughly translates as “preparation for the follow-up.” So, after the meeting, it is common to send another document with a “thank you” for attending the productive meeting and a short list of conclusions reached at the meeting.

Priya (UAE): In the Middle East, relationships rather than time are the focus. Also, given the busy roads and so on, meetings are expected to start late. So one always provides for a delayed start and ending. Because of the focus on relationships, to be the most effective in the Middle East, expect the first five minutes of a business meeting conversation to be dominated by personal talk during which families and other informal topics are asked about. It is considered rude to immediately jump into a business conversation.

Kaz (Japan): If the meeting is supposed to start at 2 P.M., it is acceptable until 2:10. A person at a higher position—a manager or a team leader, for example—may show up fifteen to thirty minutes late and no one would blame.

As I worked at a foreign (U.S.-based) company, I noticed that meetings would be done on time if not earlier. In comparison, meetings with Japanese companies fully occupied the scheduled time and in worst cases went on more than an hour longer. (Japanese companies seem to care more about beginning on time than wrapping up on time.)

Sujit (India): There is a joke that runs in India. It is called the IST, Indian Standard Time, that is generally off the actual time by over twenty minutes or so … sometimes even more! It is always good and expected that there is an agenda with timelines, else you may run a danger of huge delays. Generally meetings start on time, a small delay of a few minutes is not even considered, and delays of close to fifteen minutes are considered normal. The situation is changing, though, and more often than not, meetings begin on time. My experience has been that as compared to American or British professionals, Indians are pretty verbose, and that adds to the time factor. It is always recommended that there is a small cushion on the timelines to accommodate delays.

Indian professionals are known for multitasking, and one should not be surprised that a lot of going out and coming in happens during a meeting. This should not be considered insulting. With multitasking and multiple tasks handled simultaneously, checking mails or taking calls on BlackBerrys or cell phones, though not considered polite, is a normal trend and is generally accepted.

Generally, meetings are laced with snacks, tea or coffee, and so on, which is considered as a hospitality ritual.

Saada (Tanzania): To be on time means being there either five minutes before or exactly on time. Anything later will show the person lacks seriousness and is not professional. Meetings at times could get delayed if most members are late, so the start time could be 2:00 or 2:15. End time could be 4:15 or later depending on how strict the chairperson is with time.

Meetings here are extremely formal, and the person in charge of the agenda is the one who is conducting the meeting. In every meeting you will find tea, coffee, and biscuits. If meetings run into lunch, then there is a light snack. Mobile phones are usually switched off or put on silent. Texting or stepping out to take a call comes across as being rude.

Laine (Philippines): In the Philippines, people are more tolerant about timing in general, especially in local offices. In some cases, like government offices, expect to wait longer. (Hopefully this is changing!) But if you're meeting an executive of a large corporate firm or a multinational, he or she is likely to be more time conscious. In any case, it is still advisable to always be on time. Traffic in cities like Manila can be quite troublesome, so allow some extra time to get to your meetings and plan your route in advance.

DISTANCE AND TOUCH

When it comes to distance and touch, people's comfort levels differ measurably across cultures. Some cultures formally distance themselves from one another when doing business, getting close only to shake hands or exchange business cards. Other cultures conduct business at a much closer interpersonal distance and use a greater frequency of touch cues.

Marc (UK): Brits stand at least two feet apart—and hardly ever touch business colleagues. Sometimes they might tap the table with a pen close to the person they are connecting with, but bodily contact is avoided.

Paulo (Brazil): Distance isn't an issue for us. We can sit close or even stand very close to our business colleagues. Hugging and touching are quite common in Brazil—especially in comparison with other cultures.

Helen (China): The Chinese tend to stand close in a conversation, less than two feet, but more than one foot. Sometimes they touch the other person's arm or back or grasp a shoulder to show that they have established a trusting relationship. The Chinese may also bump into you while walking or talking. It's not considered rude in Chinese culture to bump into other people.

Judette (Trinidad and Tobago): Certainly men will not touch much, if at all; a pat on the shoulder at the end of a good meeting may be all. We stand about two feet apart.

Jennifer (Australia): Although known for their relaxed and easygoing countenance, Australians are surprisingly uptight about distance. If you stand closer than two feet, it is considered intense and possibly an indication that you are to be told something very confidential. Unless there was a preexisting close relationship, an Australian would take a step backwards or sideways to create space. We are more comfortable with three to four feet apart.

Australians would flinch or stiffen at a touch from a business colleague. Most male executives would be concerned about the legal implications of touching a female in the workplace. If there is a light touch on the arm or shoulder, it communicates “I am like you; I am one of you,” or “I appreciate what you have done.”

Roberto (Mexico): You stand close and constantly touch. If you don't know the other person well, you would touch mainly the arm, shoulder, and back. If you know the person well, sometimes you lightly touch the leg if you are sitting next to each other.

Silvia (Germany): Germans are more comfortable when keeping a good arm's distance away. And you won't see much touching, but it is more common in southern Germany.

Priya (UAE): Here people stand close, as the concept of personal space does not exist; instead it is about proximity, as all transactions are dominated by relationships. In fact, if people stand too far apart, it is seen as a negative, and you can be asked why you are standing at a distance. However, not much touching happens in deference to the laws of the land where members of the opposite sex not related to each other by marriage are not supposed to touch each other in public.

Kaz (Japan): We prefer to be three to four feet apart. Two feet makes us feel almost uncomfortable. (A close physical proximity is unexpected except for the rush-hour trains, literally packed with passengers, where we simply give up and accept the situation.) In Japan, people hardly ever touch their business colleagues, especially these days. Sometimes male managers pat their male colleagues' shoulders for encouragement.

Sujit (India): About two feet is a good distance. However, sometimes I have experienced senior professionals coming too close and almost whispering; it could be their style, but it generally puts people off! It is generally good to have a decent distance during conversations, a demeanor that is respectful, and a body language that is open (no folded arms close to the chest!). Shorter distances are okay on an evening out and over drinks. Moreover, when it comes to ladies, sufficient care needs to be taken on how close one wants to stand and talk.

Generally in a business scenario, the only touch that happens is the handshake on meeting and parting. Indians are generally warm, and an innocuous pat to congratulate or asking someone to stop is not seen as offensive. An innocent touch on the arm and shoulder to reassure someone is a normal behavior. A high-five among peers during a meeting is also a way of showcasing solidarity.

Saada (Tanzania): At least a foot apart. I normally would touch or tap on the wrist or shoulder, but very lightly.

Laine (Philippines): Two feet should be a good estimate for the Philippines, regardless of gender. For women, more senior executives would tend to be more formal and conscious of propriety. Touching is usually not appropriate among business colleagues, especially if in a meeting context. Maybe during cocktails, or in a more casual atmosphere, a light tap on the arm or shoulder, especially among colleagues who know each other well, is acceptable.

EYE CONTACT

The rules of eye contact vary from culture to culture. In the United States (and other countries), people are taught to look at each other during conversations, but in some cultures, minimizing eye contact is considered a sign of respect.

Marc (UK): Brits use a reasonable amount of eye contact, but there's much looking into the air when discussing controversial issues.

Paulo (Brazil): Eye contact is common and shows how confident you are about an issue.

Helen (China): The Chinese tend to avoid eye contact. It's considered impolite if you look straight in the eyes of the other person. The Chinese can be very uncomfortable with eye contact.

Judette (Trinidad and Tobago): We like eye contact, but there's a fine line between men and women. If a man, don't take the woman's warmth and friendliness as a sign that the lady is interested in you—particularly at a Carnival party! They're just enjoying themselves. If a woman, aim for courtesy and warm interest, but be careful about sending mixed messages.

Jennifer (Australia): Australians hold eye contact to denote trustworthiness and respect. Someone who does not look at you is probably telling fibs or doesn't think highly of you. Someone who holds prolonged eye contact without polite breaks will make others uncomfortable. Prolonged eye contact can be used as a deliberate tactic to unsettle the other business partner.

Roberto (Mexico): Always look at someone in the eyes.

Silvia (Germany): Eye contact is necessary. You won't be trusted without it.

Priya (UAE): A reasonable amount of eye contact is expected to actually make any sort of an impact. However, staring is considered rude.

Kaz (Japan): Only the leader of the business meeting or the speaker will make a reasonable amount of eye contact, but if a participant makes just as much eye contact, it may be interpreted as rejecting the idea or having something to say against it. In other words, a minimum amount of eye contact is appropriate in Japan between businesspeople.

Sujit (India): I would personally like to believe that Indians operate more on the trust factor, and one of the key essentials to generate trust is empathetic eye contact during a conversation. It also depicts confidence. Although eye contact is important, unnecessary staring is considered discourteous, especially if one is looking too long at a lady participant.

Saada (Tanzania): Too much eye contact could be seen as domineering. It also depends on the sex: male to male, if it is prolonged a little, could be seen as okay, but male to female could be seen as being aggressive or overconfident.

Laine (Philippines): Eye contact is very important to show engagement and sincerity. In the Philippines, though, you may still encounter those who remain quite self-conscious when looking people in the eye or maintaining eye contact. You will find that some may still tend to look away or down on occasions. But this is less true now, especially among the younger executives.

SEATING

You are the guest—so where will you be seated at the conference table? And where will your host sit? It all depends….

Marc (UK): Senior execs always sit at the head of table. Any U.S. members will tend to sit in the middle and upset the hierarchy of above- and below-the-salt protocols. This goes back to medieval times when salt was a luxury and the nobility would always sit at or above the salt, whereas more lowly types would gravitate toward the bottom half of the table.

Paulo (Brazil): The most important senior executive usually sits at the head of the table or in the middle. His or her assistants can sit next to him (on the right and left). We would seat an American executive across from our senior executive or on his right.

Helen (China): The most senior Chinese executive would sit where he or she could face the door across the table. The Chinese believe that position gives the person a lot of power and control. The American executive would be seated next to the most senior executive.

Judette (Trinidad and Tobago): Wait for the most senior persons to sit; business partners normally sit opposite.

Jennifer (Australia): We're very free-form in seating at conference tables. There is usually some discussion of “Where do you want me to sit?” but unless it is a very formal meeting, the most senior executive sits at the seat that is left for him or her (as this person is usually late) owing to the fact he or she is a Very Important Person. The person running the meeting sits at the head of the table usually. He or she may also choose to sit at the middle of the table so as to be seen to be inclusive of others and not hierarchical.

Roberto (Mexico): The most senior always sits at the head of the table.

Silvia (Germany): The German executive will sit at the head of the table or in the middle of one of the sides. If he is at the head, he will probably want an aide to be seated next to him. The American exec will be seated at one of the sides—across from the exec if he's in the middle—or down the table if he's at the end.

Priya (UAE): The most senior head would sit at the head of the table, and he would lead the discussion.

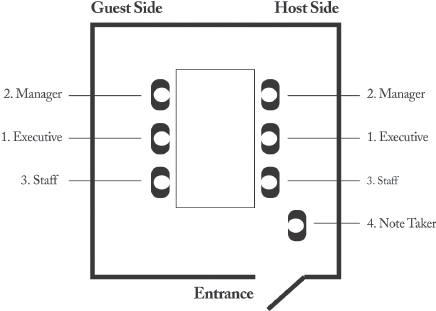

Kaz (Japan): In Japan, the guests take seats at the far side of the table from the entrance door. At each side of the table, the most senior executive sits in the middle, a person second in the hierarchical order takes the far end of the table, and staff sit closest to the door.

Seating arrangements for a Japanese business meeting

Sujit (India): While the most senior executive occupies the narrow end of the conference table (the head position), I feel it depends on the situation and the type of meeting. Generally this position is reserved for the senior-most people for any general organizational meeting.

For a conference table meeting, two scenarios come to my mind:

- A negotiation when the American is a supplier to the Indian buyer. The instinctive position that the buyer would take would be the center of one side of the table, flanked by his or her team. The supplier and that team would occupy the space across to have a face-to-face meeting. Generally the buyer team would be larger than the supplier team. This is also to convey in a nonverbal way a commanding position in one's own sphere of influence.

- A general sales pitch. This is a situation when spontaneously the most senior executive would take the head position. This is the position that has the best view of all participants. The presenters would be in a row perpendicular and at the other end to operate and present on the screen facing the head position. (While the senior-most person gets to see the screen straight, the others generally have to turn their necks right or left depending on the side of the table occupied!) The nonverbal cue here is that the person occupying the head position is in control and has to grasp the situation correctly, as he is the one responsible for the final decision.

Saada (Tanzania): The person who is chairing the meeting sits at the head of the table, and his or her team would be beside him or her. The visitors would sit on the opposite side. This is a typical setup for external meetings. For internal meetings, the person chairing the meeting sits at the head, the management team next to him or her, and the other invited team members on the opposite side.

Laine (Philippines): Senior executives tend to take the head of the table. The guest would most likely take his or her cue from the host. The host may point to the seat as he or she invites the guest to sit down. It is still safe to sit across if the table is small; sitting beside each other has become acceptable. If the guest is conscious of proximity, he or she can skip one seat.

EMOTIONS

The display of emotions allowed (even expected) in a business meeting differs greatly from culture to culture. What will be the reaction if you laugh out loud, rant and rave about some negotiation point, disclose personal information, or burst into tears? Here's what the panel had to say.

Marc (UK): Emotion is allowed more than in Nordic countries, whom we consider to be a bit buttoned up. Jokes are preferred to raw emotion, and sarcasm and irony are much valued. Passion is limited unless the subject of sport comes up. To shout is an admission of defeat, and although laughter is encouraged, tears are a source of major embarrassment. Coolness and aloof detachment are valued. Anything else is described as “losing it.”

Paulo (Brazil): We are very emotional. We usually start a meeting talking about our families, friends, personal lives, and so on, and after a warm-up, we get into business. Examples and personal information are often used during meetings.

Helen (China): The Chinese can get emotional in business meetings, including laughing, or raising their voices. Talking loud is not considered rude.

Judette (Trinidad and Tobago): The T&T private sector tends to be less formal than other parts of the Caribbean. Our culture is jovial, and on many occasions a joking and jesting atmosphere is the preferred way to start a meeting. Crying may be perceived as irrational.

Jennifer (Australia): Australians prefer business dealings to be emotionally neutral. Anger, distress, and excessive emotion will make an Australian uncomfortable in the workplace. Most emotion in the workplace is perceived as career limiting.

Roberto (Mexico): Emotion is part of Mexican people. It will always be shown. There's usually a bit of comedy if the air gets tense, and a lot of banter.

Silvia (Germany): Some emotions are acceptable. You should expect to see displays of power and even rage (raised voice, accusatory tone, emphatic speech). It's a normal negotiation tactic to begin with an attack. What they are looking for is your reaction. If you are cowed, they will tend to dismiss you. If you respond with confident and powerful body language, you will be respected.

Priya (UAE): This is a part of the world where emotions and relationships dominate transactions. So people do get emotional and show their displeasure. However, in certain places like Dubai, extreme aggression and even calling people names can land you in jail.

Kaz (Japan): Traditionally it is not encouraged to show emotions, as Japan has long cherished a high-context culture, and people have been expected to “sense” what the others mean without explicit emotional expressions. Yet as Japan shifts to a low-context society, emotional expressions are more encouraged than before. Another aspect of emotional expression in Japan is that people follow the expressions of others, such as laughter, simply to “do the same.” For instance, even if we do not understand or appreciate the joke, we reciprocate the laughter or a smile as good manners if other people laugh.

Sujit (India): Although Indians are emotional, not many would show this side in a business dealing. Laughter and lighter moments are always accepted well and act as stress busters. A demonstration of concern, empathy, and cohesion helps gather trust faster. But sarcastic, racist, and domineering emotions get easily manifested in conversations and body language, and these are a big put-off during a business meeting or any other meeting.

Saada (Tanzania): One is expected to be calm and cool throughout the meeting. If you are angry, you are supposed to show it through your facial expression and tone of voice, but not to shout or scream. Foul or loose language is not accepted and is seen as demeaning. Breaking down in tears for a woman is seen as a sign of weakness, and for a man it is unacceptable. It also comes across as being unprofessional. Jokes are seen as okay as long as they are light ones. It is seen as okay to laugh at a joke, but not when one is trying to say or express something.

Laine (Philippines): It is best to respond or act with a degree of restraint and propriety. You can smile or laugh when the situation calls for it—and in a culture of happy people, this is more a norm than an exception. Shouting or emotional outbursts are not recommended even if these acts are just forms of expression and not intentionally meant to embarrass. Diplomacy in word and action is encouraged. It is also advisable to express emotions one-on-one rather than in front of the whole group, especially if not everyone is involved in the situation. Filipinos find it difficult to detach an issue or discussion from the person. They tend to get affected by an open confrontation, or sometimes by an opposing idea or comment. Generally, they are very sensitive.

WOMEN

Many of the panelists said that their advice would be the same if I were coaching a female executive for a meeting in their cultures. A typical comment was, “Women are viewed as business counterparts and are treated (and expected to behave) similarly to men in senior executive roles.” There were, however, some exceptions:

Marc (UK): Men never offer to make refreshments, and they expect others to pour the tea. If there is one woman among a dozen men, no one will pour tea unless she takes on the responsibility. We have the phrase in all-male meetings: “Who will be mother?”

Helen (China): Chinese men may compliment women's appearance, such as by using the word “attractive” or “pretty.” Some language may sound inappropriate in American culture, but they are just trying to be friendly.

Roberto (Mexico): Mexico is mainly a male-driven country. Things are changing, but how people act definitely changes if there is a woman present. If a group is made up of only men, usually the banter can get elevated, particularly if they are all peers; if there is one or more senior men, the setting is more formal. If there is a woman, this is also the case, unless she is well known to everyone, at which stage everyone relaxes more.

Silvia (Germany): People outside Germany believe that the country is rather advanced in workplace gender issues, but this is not really the case. Women in senior leadership positions are still rare. My best advice for visiting women executives is to stay very business focused. Tone down feminine flirtatious behavior. Instead, project confidence and power, and you'll be fine.

Sujit (India): Women executives certainly have an advantage. Although we do have many women business leaders, in India women are viewed with more empathy than men, even in the corporate world. The adage “Women can get things done with a smile” is sometimes true!

Laine (Philippines): People may take a less strong or softer approach when dealing with women counterparts out of traditional respect, but this is becoming less the case as women take on bigger roles. This is a reflection that women are increasingly being seen and treated as equals.

Paulo (Brazil): There are no differences between men and women in the workplace. Women should be focused on business and will be respected like all men. There are few women who take leadership in Brazil, but it is becoming more and more common.

CLOSING WORDS OF ADVICE

I asked the panelists if they had any additional words of advice for my U.S. executive. Here are their replies:

Judette (Trinidad and Tobago): The main “beef” with American businesspeople is their tendency to come over as arrogant and closed and to run roughshod over others. Relationships matter when doing business in T&T—invest the time in getting to know the culture, showing an openness to it. Don't just hang out with fellow Americans because that is your comfort zone. And be prepared to loosen up a little. Go to the local liming spots (neighborhood bars, clubs, and restaurants), join the Cricket Club, and show that you are not always so intense.

Sujit (India): As India is a very family oriented, affable society, good trustworthy relationships play an important role when doing business, and things work out faster if a relation of trust is built. My recommendation would be to have a consistent positive forward-looking emotion even if one does not get the business one hoped for, as there is always a next time.

Roberto (Mexico): Latin American culture is based on relationships and not business. In any meeting, 60 percent of the time will be spent in “How's the family? How's business? What do you think about the current situation?” Once everyone is relaxed, you talk business. People who approach business first without concern for personal matters usually fail in Mexico. There are always exceptions, but this is generally how I see it.

Silvia (Germany): Germany is a large country. Southern Germany is very different from the north (Catholic South vs. Protestant North, and so on)—and East Germany, which used to be part of the Socialist bloc, has its own unique history. When preparing for a meeting, try to understand these differences. Appreciate historical backgrounds and honor experiences that might contradict your way of looking at life.

Do the Right Thing

UK/Irish Republic: men and women—a handshake

Brazil/S. America: men and women—a handshake; with friends, a hug or kiss

Australia: men and women—a firm handshake

Mexico/Latin America: a handshake initially; when more familiar, men hug, women kiss

Germany: men and women—a firm, determined, nononsense handshake, with eye contact to match

Western Europe generally (France, Italy, Spain, Low Countries, and so on): a friendly, not-quite-so-determined handshake, with friendly eye contact

UAE/Middle East (generally): men and women—a handshake; a kiss between women who know one another well

Saudi Arabia and some other Middle Eastern countries: a slight bow, sometimes with hand on heart—no handshake; if in doubt, watch others

Japan/China/Far East generally: men and women—a handshake; if both parties are Asian, a bow, if preferred; modest eye contact

India: men and women—a firm, warm handshake

Africa (Central and Southern generally): men and women—a handshake

North Africa generally: men and women—see Middle East, above

The Philippines: men and women—a firm handshake

Business Cards

UK/Irish Republic: seldom exchanged, except to provide contact info if not otherwise available or if, in future, one-to-one contact will be required

Brazil/S. America: not handed out usually, but often laid on the conference table to assist in identifying everyone

Australia: not handed out indiscriminately—only in cases of important relationships

Mexico/Latin America: usually handed out during the greeting

Germany: treated with great importance; often used to check if your title matches your company status

Western Europe generally: less formal; used for contact info mainly (Italians sometimes don't bother—which drives Germans crazy!)

UAE/Middle East generally: handed out formally during greetings for identification purposes

Japan/China/Far East: very important as part of the formal greeting; also important to treat received cards with respect and interest

India: again, formal exchange of cards very important

Africa: handed round at the beginning of a meeting

The Philippines: important

Time

UK/Irish Republic: For meetings, arriving five to eight minutes late is just about okay if unavoidable. Fifteen minutes late is rude. Meetings may overrun by fifteen minutes, so tailor your next appointments accordingly.

Brazil/S. America: Time is no big deal in Latin America. Meetings may begin up to thirty minutes late—and stop times are almost unheard of. Try to be on time for one-on-one meetings, though.

Australia: Be on time for meetings—even if they start a few minutes late.

Mexico/Latin America: See Brazil.

Germany: Arrive early. (It shows enthusiasm!) You won't be lonely—your German colleagues will have arrived early, too.

Western Europe generally: Try to be on time for meetings. If you have an excuse, a few minutes late is okay. But, as in the UK, more than a few is rude.

UAE/Middle East generally: Typical of the mysterious Middle East, it is bad manners to arrive late for meetings, though meetings never start on time.

Japan/China/Far East: In Japan, meetings tend to start on or nearly on time, but may overrun by as much as an hour. In China, time seems to play no controlling role at all—meetings are often convened at a few minutes' notice, and end when they end. Nobody seems bothered by this, though—and believe me, business does get done!

India: Despite the notorious Indian Standard Time (IST), meetings tend to start within ten to fifteen minutes of the scheduled time—but very often end when the chair decides there is no more business to do.

Africa: In general, arrive five minutes early if you want to be taken seriously.

The Philippines: Arrive on time—or nearly—but expect to wait up to thirty minutes for meetings to begin.

Space

UK/Irish Republic: Stand about two feet apart. No touching.

Brazil/S. America: Stand wherever you feel comfortable. Touching is fine.

Australia: Don't be fooled by the laid-back rep.

Crocodile Dundee is only a movie. Aussies, in fact, are rather straitlaced folk. Three to four feet apart is comfortable standing space, and there is definitely no touching.

Mexico/Latin America: Two feet apart or closer is appropriate; touching is okay.

Germany: Arm's length apart is appropriate; there is no touching.

W. Europe generally: Stand two feet apart. Touching in some countries is normal, but watch the others for cues.

UAE/Middle East: Stand as close as you like, but there should be no touching.

Japan/China/Far East: Stand three to four feet apart in Japan, and there should be no touching. In China, stand two feet apart, or closer if it's comfortable. Touching is not common social practice, but okay as a way to show trust.

India: Stand two feet apart. Some touching is okay to show friendship or trust.

Africa: Stand two feet apart; there should be minimal or no touching.

The Philippines: Stand two feet apart. Touching is generally seen as inappropriate.

Eye Contact

UK/Irish Republic: Eye contact should not be too direct for too long, especially with Brits, who tend to feel they're being watched rather than looked at.

Brazil/S. America: The more eye contact, the more confident and honest you appear to be.

Australia: Lack of eye contact makes you seem untrustworthy. Constant eye contact, however, causes unease.

Mexico/Latin America: See Brazil.

Germany: Don't flinch! Flinchers can't be trusted.

W. Europe generally: Maintain steady eye contact. Keep it friendly.

UAE/Middle East: Reasonable eye contact suggests honesty and seriousness. Anything like staring, however, is considered rude.

Japan/China/Far East: In Japan, minimal eye contact is considered proper. Too much indicates a negative or even hostile response to colleagues. In China, it's best to avoid direct eye contact. Looking straight into another person's eyes is impolite.

India: Emphatic eye contact indicates trust and confidence. Prolonged staring, however, is discourteous, especially with female colleagues.

Africa: Modest eye contact is the best policy.

The Philippines: Eye contact shows interest and sincerity.

Emotion

UK/Irish Republic: Normal emotion is perfectly acceptable—not too much passion, however. Shouting is always read as weakness. Wit, irony, a bit of sarcasm are all valued. Tears are not, however. Curiously, the more detached one appears to be, the more powerfully one comes across.

Brazil/S. America: Friendly, emotional talk about family, friends, and personal lives will usually be the starting point for conferences, seminars, and so on. Being open emotionally is a way of demonstrating friendliness, interest, and seriousness.

Australia: Emotional neutrality is the key here. Emotional display of any kind makes Australians feel uncomfortable and makes you seem limited.

Mexico/Latin America: See Brazil.

Germany: Power displays, even anger and verbal attacks, are tactically normal in negotiations and meetings. Yell back, and you'll be respected. Look uneasy, and they'll think there's something wrong with you.

W. Europe generally: Yelling and crying aren't good moves. Friendliness, banter, and a little warmth are fine. Nearly all Europeans speak some English, and many speak it very well—including the Germans—so expect to get as good as you give.

UAE/Middle East: Always behave politely without being standoffish. Emotion and personal relations play a central role in Middle Eastern business. But never lose your temper or make rude gestures—you could end up in jail.

Japan/China/Far East: The Chinese can become quite animated and even loud in business meetings. Laughing, yelling, and so on are not considered rude. In Japan, they are. Emotional display is considered unseemly there. Elsewhere in the Far East, emotional customs differ considerably. So simply be polite and quietly spoken and take your cues from the others.

India: Be politely friendly. Keep the emotional level down.

Africa: Stay calm and cool.

The Philippines: Be polite. Keep your emotions under control without being aloof.