CHAPTER 2

Supply Chain Operations

Planning and Sourcing

After reading this chapter you will be able to

- Gain a conceptual appreciation of the business operations in any supply chain

- Exercise an executive-level understanding of operations involved in supply chain planning and sourcing

- Start to assess how well these operations are working within your own company

As the saying goes, “It's not what you know, but what you can remember when you need it.” Since there is an infinite amount of detail in any situation, the trick is to find useful models that capture the salient facts and provide a framework to organize the rest of the relevant details. The purpose of this chapter is to provide some useful models of the business operations that make up the supply chain.

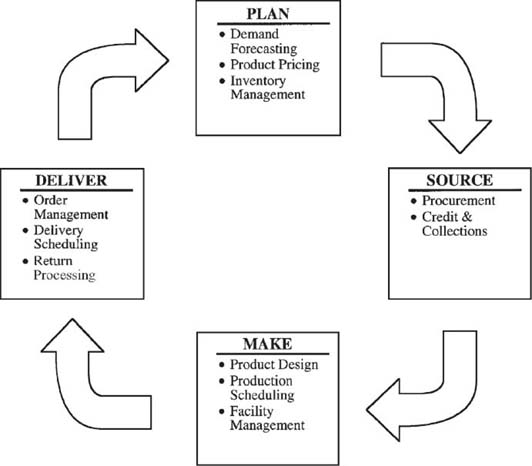

A Useful Model of Supply Chain Operations

In the first chapter we saw that there are five drivers of supply chain performance. These drivers can be thought of as the design parameters or policy decisions that define the shape and capabilities of any supply chain. Within the context created by these policy decisions, a supply chain goes about doing its job by performing regular, ongoing operations. These are the “nuts and bolts” operations at the core of every supply chain.

As a way to get a high-level understanding of these operations and how they relate to each other, we use a simplified version of the supply chain operations reference (SCOR) model developed by the Supply Chain Council (Supply Chain Council Inc., 12320 Barker Cypress Rd, Suite 600, PMB 321, Cypress, TX 77429, www.supply-chain.org). Readers can get information on the full model at their web site. Our simplified model identifies four categories of operations:

- Plan

- Source

- Make

- Deliver

Plan

This refers to all the operations needed to plan and organize the operations in the other three categories. We will investigate three operations in this category in some detail: demand forecasting, product pricing, and inventory management.

Source

Operations in this category include the activities necessary to acquire the inputs to create products or services. We look at two operations here. The first, procurement, is the acquisition of materials and services. The second operation, credit and collections, is not traditionally seen as a sourcing activity but it can be thought of as, literally, the acquisition of cash. Both these operations have a big impact on the efficiency of a supply chain.

Four Categories of Supply Chain Operations

Within the constraints set by decisions about the four supply chain drivers, these business operations do the work that makes the supply chain a reality.

Make

This category includes the operations required to develop and build the products and services that a supply chain provides. Operations that we discuss in this category are product design, production management, and facility and management. The SCOR model does not specifically include the product design and development process, but it is included here because it is integral to the production process.

Deliver

These operations encompass the activities that are part of receiving customer orders and delivering products to customers. The three operations we review are management, product delivery, and return processing. These are the operations that constitute the core connections between companies in a supply chain.

The rest of this chapter presents further detail in the categories of Plan and Source. There is an executive-level overview of the three main operations that constitute the planning process and two operations that comprise the sourcing process. Chapter 3 presents an executive overview of the key operations in making and delivering.

Demand Forecasting and Planning (Plan)

Supply chain management decisions are based on forecasts that define which products will be required, what amount of these products will be called for, and when they will be needed. The demand forecast becomes the basis for companies to plan their internal operations and to cooperate among each other to meet market demand.

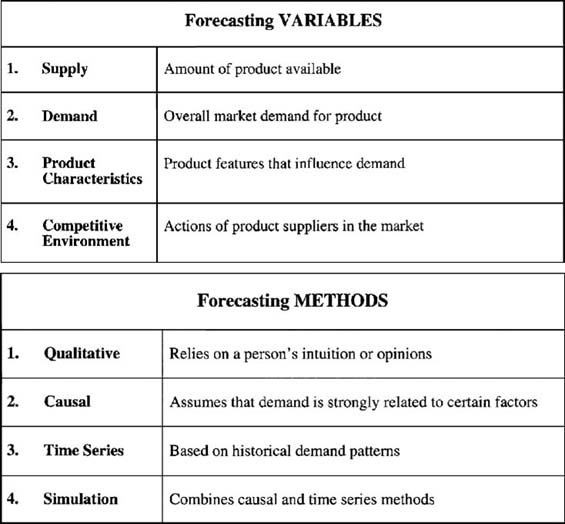

All forecasts deal with four major variables that combine to determine what market conditions will be like. Those variables are:

- Supply

- Demand

- Product Characteristics

- Competitive Environment

Supply is determined by the number of producers of a product and by the lead times that are associated with a product. The more producers there are of a product and the shorter the lead times, the more predictable this variable is. When there are only a few suppliers or when lead times are longer, then there is more potential uncertainty in a market. Like variability in demand, uncertainty in supply makes forecasting more difficult. Also, longer lead times associated with a product require a longer time horizon over which forecasts must be made. Supply chain forecasts must cover a time period that encompasses the combined lead times of all the components that go into the creation of a final product.

Demand refers to the overall market demand for a group of related products or services. Is the market growing or declining? If so, what is the yearly or quarterly rate of growth or decline? Or maybe the market is relatively mature and demand is steady at a level that has been predictable for some period of years. Also, many products have a seasonal demand pattern. For example, snow skis and heating oil are more in demand in the winter, and tennis rackets and sun screen are more in demand in the summer. Perhaps the market is a developing market—the products or services are new and there is not much historical data on demand or the demand varies widely because new customers are just being introduced to the products. Markets where there is little historical data and lots of variability are the most difficult when it comes to demand forecasting.

Product characteristics include the features of a product that influence customer demand for the product. Is the product new and developing quickly like many electronic products or is the product mature and changing slowly or not at all, as is the case with many commodity products? Forecasts for mature products can cover longer timeframes than forecasts for products that are developing quickly. It is also important to know whether a product will steal demand away from another product. Can it be substituted for another product? Or will the use of one product drive the complementary use of a related product? Products that either compete with or complement each other should be forecasted together.

Competitive environment refers to the actions of a company and its competitors. What is the market share of a company? Regardless of whether the total size of a market is growing or shrinking, what is the trend in an individual company's market share? Is it growing or declining? What is the market share trend of competitors? Market share trends can be influenced by product promotions and price wars, so forecasts should take into account such events that are planned for the upcoming period. Forecasts should also account for anticipated promotions and price wars that will be initiated by competitors.

Forecasting Methods

There are four basic methods to use when doing forecasts. Most forecasts are done using various combinations of these four methods. Chopra and Meindl define these methods as:

- Qualitative

- Causal

- Time Series

- Simulation

Qualitative methods rely upon a person's intuition or subjective opinions about a market. These methods are most appropriate when there is little historical data to work with. When a new line of products is introduced, people can make forecasts based on comparisons with other products or situations that they consider similar. People can forecast using production adoption curves that they feel reflect what will happen in the market.

Causal methods of forecasting assume that demand is strongly related to particular environmental or market factors. For instance, demand for commercial loans is often closely correlated to interest rates. So if interest rate cuts are expected in the next period of time, then loan forecasts can be derived using a causal relationship with interest rates. Another strong causal relationship exists between price and demand. If prices are lowered, demand can be expected to increase and if prices are raised, demand can be expected to fall.

Time series methods are the most common form of forecasting. They are based on the assumption that historical patterns of demand are a good indicator of future demand. These methods are best when there is a reliable body of historical data and the markets being forecast are stable and have demand patterns that do not vary much from one year to the next. Mathematical techniques such as moving averages and exponential smoothing are used to create forecasts based on time series data. These techniques are employed by most forecasting software packages.

Simulation methods use combinations of causal and time series methods to imitate the behavior of consumers under different circumstances. This method can be used to answer questions such as what will happen to revenue if prices on a line of products are lowered or what will happen to market share if a competitor introduces a competing product or opens a store nearby.

Few companies use only one of these methods to produce forecasts. Most companies do several forecasts using several methods and then combine the results of these different forecasts into the actual forecast that they use to plan their businesses. Studies have shown that this process of creating forecasts using different methods and then combining the results into a final forecast usually produces better accuracy than the output of any one method alone.

Regardless of the forecasting methods used, when doing forecasts and evaluating their results it is important to keep several things in mind. First of all, short-term forecasts are inherently more accurate than long-term forecasts. The effect of business trends and conditions can be much more accurately calculated over short periods than over longer periods. When Wal-Mart began restocking its stores twice a week instead of twice a month, the store managers were able to significantly increase the accuracy of their forecasts because the time periods involved dropped from two or three weeks to three or four days. Most long range, multiyear forecasts are highly speculative.

Aggregate forecasts are more accurate than forecasts for individual products or for small market segments. For example, annual forecasts for soft drink sales in a given metropolitan area are fairly accurate but when these forecasts are broken down to sales by districts within the metropolitan area, they become less accurate. Aggregate forecasts are made using a broad base of data that provides good forecasting accuracy. As a rule, the more narrowly focused or specific a forecast is, the less data is available and the more variability there is in the data, so the accuracy is diminished.

Finally, forecasts are always wrong to a greater or lesser degree. There are no perfect forecasts and businesses need to assign some expected degree of error to every forecast. An accurate forecast may have a degree of error that is plus or minus 5 percent. A more speculative forecast may have a plus or minus 20 percent degree of error. It is important to know the degree of error because a business must have contingency plans to cover those outcomes. What would a company do if raw material prices were 5 percent higher than expected? What would it do if demand was 20 percent higher than expected?

Aggregate Planning

Once demand forecasts have been created, the next step is to create a plan for the company to meet the expected demand. This is called aggregate planning, and its purpose is to satisfy demand in a way that maximizes profit for the company. The planning is done at the aggregate level and not at the level of individual stock keeping units (SKUs). It sets the optimum levels of production and inventory that will be followed over the next 3 to 18 months.

The aggregate plan becomes the framework within which short-term decisions are made about production, inventory, and distribution. Production decisions involve setting parameters such as the rate of production and the amount of production capacity to use, the size of the workforce, and how much overtime and subcontracting to use. Inventory decisions include how much demand will be met immediately by inventory on hand and how much demand can be satisfied later and turned into backlogged orders. Distribution decisions define how and when product will be moved from the place of production to the place where it will be used or purchased by customers.

TIPS & TECHNIQUES

The Four Forecasting Variables and the Four Forecasting Methods

There are three basic approaches to take in creating the aggregate plan. They involve trade-offs among three variables. Those variables are: (1) amount of production capacity; (2) the level of utilization of the production capacity; and (3) the amount of inventory to carry. We look briefly at each of these three approaches. In actual practice, most companies create aggregate plans that are a combination of these three approaches.

- Use Production Capacity to Match Demand. In this approach the total amount of production capacity is matched to the level of demand. The objective here is to use 100 percent of capacity at all times. This is achieved by adding or eliminating plant capacity as needed and hiring and laying off employees as needed. This approach results in low levels of inventory but it can be very expensive to implement if the cost of adding or reducing plant capacity is high. It is also often disruptive and demoralizing to the workforce if people are constantly being hired or fired as demand rises and falls. This approach works best when the cost of carrying inventory is high and the cost of changing capacity plant and workforce—is low.

- Utilize Varying Levels of Total Capacity to Match Demand. This approach can be used if there is excess production capacity available. If existing plants are not used 24 hours a day and 7 days a week then there is an opportunity to meet changing demand by increasing or decreasing utilization of production capacity. The size of the workforce can be maintained at a steady rate and overtime and flexible work scheduling used to match production rates. The result is low levels of inventory and also lower average levels of capacity utilization. The approach makes sense when the cost of carrying inventory is high and the cost of excess capacity is relatively low.

- Use Inventory and Backlogs to Match Demand. Using this approach provides for stability in the plant capacity and workforce and enables a constant rate of output. Production is not matched with demand. Instead inventory is either built up during periods of low demand in anticipation of future demand or inventory is allowed to run low and backlogs are built up in one period to be filled in a following period. This approach results in higher capacity utilization and lower costs of changing capacity but it does generate large inventories and backlogs over time as demand fluctuates. It should be used when the cost of capacity and changing capacity is high and the cost of carrying inventory and backlogs is relatively low.

Product Pricing (Plan)

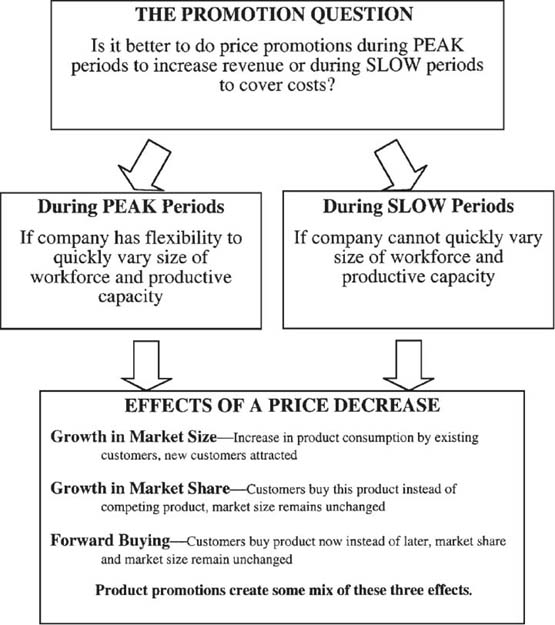

Companies and entire supply chains can influence demand over time by using price. Depending how price is used, it will tend to maximize either revenue or gross profit. Typically marketing and salespeople want to make pricing decisions that will stimulate demand during peak seasons. The aim here is to maximize total revenue. Often financial or production people want to make pricing decisions that stimulate demand during low periods. Their aim is to maximize gross profit in peak demand periods and generate revenue to cover costs during low demand periods.

Relationship of Cost Structure to Pricing

The question for each company to ask is, “Is it better to do price promotion during peak periods to increase revenue or during low periods to cover costs?” The answer depends on the company's cost structure. If a company has flexibility to vary the size of its workforce and productive capacity and the cost of carrying inventory is high, then it is best to create more demand in peak seasons. If there is less flexibility to vary workforce and capacity and if cost to carry inventory is low, it is best to create demand in low periods.

An example of a company that can quickly ramp up production would be an electronics component manufacturer. Such companies have invested in plant and equipment that can be quickly reconfigured to produce different final products from an inventory of standard component parts. The finished goods inventory is expensive to carry because it soon becomes obsolete and must be written off.

These companies are generally motivated to run promotions in peak periods to stimulate demand even further. Since they can quickly increase production levels, a reduction in the profit margin can be made up for by an increase in total sales if they are able to sell all the product that they manufacture.

A company that cannot quickly ramp up production levels is a paper mill. The plant and equipment involved in making paper is very expensive and requires a long lead time to build. Once in place, a paper mill operates most efficiently if it is able to run at a steady rate all year long. The cost of carrying an inventory of paper products is less expensive than carrying an inventory of electronic components because paper products are commodity items that will not become obsolete. These products also can be stored in less expensive warehouse facilities and are less likely to be stolen.

A paper mill is motivated to do price promotions in periods of low demand. In periods of high demand the focus is on maintaining a good profit margin. Since production levels cannot be increased anyway, there is no way to respond to or profit from an increase in demand. In periods where demand is below the available production level, then there is value in increased demand. The fixed cost of the plant and equipment is constant so it is best to try to balance demand with available production capacity. This way the plant can be run steadily at full capacity.

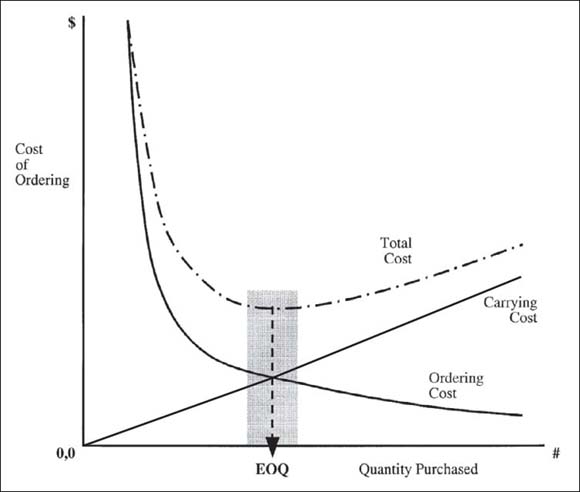

Inventory Management (Plan)

Inventory management is a set of techniques that are used to manage the inventory levels within different companies in a supply chain. The aim is to reduce the cost of inventory as much as possible while still maintaining the service levels that customers require. Inventory management takes its major inputs from the demand forecasts for products and the prices of products. With these two inputs, inventory management is an ongoing process of balancing product inventory levels to meet demand and exploiting economies of scale to get the best product prices.

TIPS & TECHNIQUES

Product Promotion and Company Cost Structure

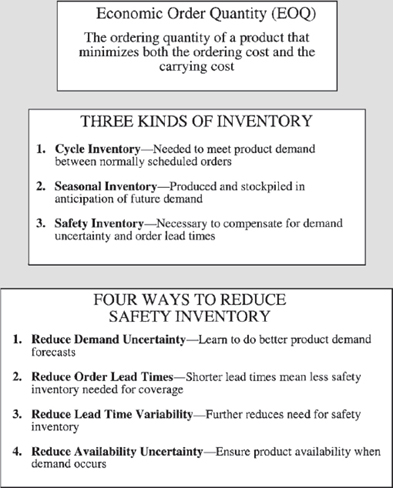

As we discussed in Chapter 1, there are three kinds of inventory: (1) cycle inventory; (2) seasonal inventory; and (3) safety inventory. Cycle inventory and seasonal inventory are both influenced by economy of scale considerations. The cost structure of the companies in any supply chain will suggest certain levels of inventory based on production costs and inventory carrying cost. Safety inventory is influenced by the predictability of product demand. The less predictable product demand is, the higher the level of safety inventory is required to cover unexpected swings in demand.

The inventory management operation in a company or an entire supply chain is composed of a blend of activities related to managing the three different types of inventory. Each type of inventory has its own specific challenges and the mix of these challenges will vary from one company to another and from one supply chain to another.

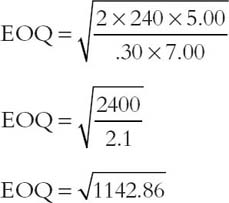

Cycle Inventory

Cycle inventory is the inventory required to meet product demand over the time period between placing orders for the product. Cycle inventory exists because economies of scale make it desirable to make fewer orders of large quantities of a product rather than continuous orders of small product quantity. The end-use customer of a product may actually use a product in continuous small amounts throughout the year. But the distributor and the manufacturer of that product may find it more cost efficient to produce and stock the product in large batches that do not match the usage pattern.

Cycle inventory is the buildup of inventory in the supply chain due to the fact that production and stocking of inventory is done in lot sizes that are larger than the ongoing demand for the product. For example, a distributor may experience an ongoing demand for Item A that is 100 units per week. The distributor finds, however, that it is most cost effective to order in batches of 650 units. Every six weeks or so the distributor places an order causing cycle inventory to build up in the distributor's warehouse at the beginning of the ordering period. The manufacturer of Item A that all the distributors order from may find that it is most efficient for them to manufacture in batches of 14,000 units at a time. This also results in the buildup of cycle inventory at the manufacturer's location.

Economic Order Quantity

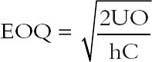

Given the cost structure of a company, there is an order quantity that is the most cost-effective amount to purchase at a time. This is called the economic order quantity (EOQ) and it is calculated as:

where:

U = annual usage rate

O = ordering cost

C = cost per unit

h = holding cost per year as a percentage of unit cost

For instance, let's say that Item Z has an annual usage rate (U) of 240, a fixed cost per order (O) of $5.00, a unit cost (C) of $7.00, and an annual holding cost (h) of 30 percent per unit. If we do the math, it works out as:

EOQ = 33.81 and rounded to the nearest whole unit, it is 34

If the annual usage rate for Item Z is 240, then the monthly usage rate is 20. An EOQ of 34 represents about seven weeks' supply. This may not be a convenient order size. Small changes in the EOQ do not have a big impact on total ordering and holding costs so it is best to round off the EOQ quantity to the nearest standard ordering size. In the case of Item Z, there may be 30 units in a case. So it would make sense to adjust the EOQ for Item Z to 30.

The EOQ formula works to calculate an order quantity that results in the most efficient investment of money in inventory. Efficiency here is defined as the lowest total unit cost for each inventory item. If a certain inventory item has a high usage rate and is expensive, the EOQ formula recommends a low order quantity which results in more orders per year but less money invested in each order. If another inventory item has a low usage rate and is inexpensive, the EOQ formula recommends a high order quantity. This means fewer orders per year but since the unit cost is low, it still results in the most efficient amount of money to invest in that item.

Seasonal Inventory

Seasonal inventory happens when a company or a supply chain with a fixed amount of productive capacity decides to produce and stockpile products in anticipation of future demand. If future demand is going to exceed productive capacity, then the answer is to produce product in times of low demand that can be put into inventory to meet the high demand in the future.

Decisions about seasonal inventory are driven by a desire to get the best economies of scale given the capacity and cost structure of each company in the supply chain. If it is expensive for a manufacturer to increase productive capacity, then capacity can be considered as fixed. Once the annual demand for the manufacturer's products is determined, the most efficient schedule to utilize that fixed capacity can be calculated.

Understanding the Economic Ordering Quantity (EOQ)

Good inventory management requires a company to know the EOQ for all the products it buys. The EOQ for different products changes over time so a company needs an ongoing measurement process to keep the numbers accurate and up to date.

This schedule will call for seasonal inventory. Managing seasonal inventory calls for demand forecasts to be accurate since large amounts of inventory can be built up this way and it can become obsolete, or holding costs can mount if the inventory is not sold off as anticipated. Managing seasonal inventory also calls for manufacturers to offer price incentives to persuade distributors to purchase the product and put it in their warehouses well before demand for it occurs.

Safety Inventory

Safety inventory is necessary to compensate for the uncertainty that exists in a supply chain. Retailers and distributors do not want to run out of inventory in the face of unexpected customer demand or unexpected delay in receiving replenishment orders, so they keep safety stock on hand. As a rule, the higher the level of uncertainty, the higher the level of safety stock that is required.

Safety inventory for an item can be defined as the amount of inventory on hand for an item when the next replenishment EOQ lot arrives. This means that the safety stock is inventory that does not turn over. In effect, it becomes a fixed asset and it drives up the cost of carrying inventory. Companies need to find a balance between their desire to carry a wide range of products and offer high availability on all of them, and their conflicting desire to keep the cost of inventory as low as possible. That balance is reflected quite literally in the amount of safety stock that a company carries.

Procurement (Source)

Traditionally, the main activities of a purchasing manager were to beat up potential suppliers on price and then buy products from the lowest-cost supplier that could be found. That is still an important activity, but there are other activities that are becoming equally important. Because of this, the purchasing activity is now seen as part of a broader function called procurement. The procurement function can be broken into five main activity categories:

- Purchasing

- Consumption Management

- Vendor Selection

- Contract Negotiation

- Contract Management

Key Points to Remember about Inventory Management

With the spread of our global, interconnected economy, there also comes the need to understand cultural and behavioral drivers that influence the procurement process. Huseyin Eskici is the head of the Procurement Department of the Istanbul Stock Exchange and he negotiates contracts with suppliers from all over the world. In an interview I posed three questions and asked him to share his insights on this topic.

![]() In your experience negotiating purchasing contracts with suppliers from different countries, what differences do you see in the negotiating process? For instance what are the negotiating differences you see between a British company or a Turkish company or a Chinese or an American company?

In your experience negotiating purchasing contracts with suppliers from different countries, what differences do you see in the negotiating process? For instance what are the negotiating differences you see between a British company or a Turkish company or a Chinese or an American company?

In my experience, negotiating purchasing contracts with suppliers from different countries has to do with their cultures. When negotiating purchasing contracts with suppliers from different countries, world-class purchasing specialists should know that they have different cultural backgrounds. What I mean by culture is “the system of values and norms that are shared among a group of people and taken togather constitute a design for living and negotiating”.

When I compare and contrast the Western or English negotiation culture with Turkish negotiation culture it is possible to list several differences. To begin with, Turkish suppliers generally give more importance and allocate more time to personal relations before and during the process of contract negotiation, whereas English suppliers prefer to start contract negotiations after completing generally accepted business protocols, such as meeting, exchanging business cards, and drinking traditional Turkish black tea or Turkish coffee. For example, when you are negotiating a contract with a Turkish supplier you may find yourself chatting about economic and political problems of the country or complaining about your organizational problems. You may even be talking about which soccer team is going to be champion this year. Almost 80 percent of the time is allocated to establishing trust and a good personal relationship and 20 percent is allocated to contract negotiation.

Turkish negotiation culture is based on verbal communication rather than on numbers, financial information, and analysis relating to the contract and the companies involved, whereas Western or English negotiation culture is mainly based on numerical communication such as facts, figures, numbers, and process analysis relating to the supply contract and the supplier firm.

Turkish culture is collectivist in nature, that is, individuals rarely prefer to take personal initiative or responsibility in making a final decision unless his or her authority is clearly defined. They prefer collective decision making when faced with critical and risky cases, whereas Western culture is individualistic in nature, that is, individuals are prone to make final decisions within their jurisdiction since they regard the success or failure as their personal responsibility. In critical cases, Turkish suppliers and negotiators like the boss or general manager to make final decisions because of our risk- averse culture.

English or U.S. suppliers do not hesitate to make decisions and conclude contracts because their limits of authority are usually clearly defined by their organizations. This relates to their individualistic cultural background. But, I have to admit, there are now many younger well-educated and trained business professionals in Turkey, and they know how to start, manage, and close a contract-negotiation process based on the Western model.

![]() You observe that negotiating behaviors are based on the culture and social structure of the country where a company is based. Can you describe some common patterns that you see when negotiating with companies from different countries.

You observe that negotiating behaviors are based on the culture and social structure of the country where a company is based. Can you describe some common patterns that you see when negotiating with companies from different countries.

I have observed that the socio-economic structure and economic and political power of countries where companies are based shape both organizational and personal negotiation styles. If we keep aside global and multi-national companies, I can describe some common patterns regarding negotiating behaviors that I have seen when negotiating a purchasing contract with companies from the United States:

Negotiators of the U.S. companies are self confident in general because their country is almost as large as a continent and they believe that their country is the most powerful one in the world. Their body language reflects that they are free and self-confident. They ideologically believe strongly in individual rights and freedoms and the superiority of private business. They are prone to use personal initiative and take risk, if necessary, to conclude a purchasing contract because their common national ideology is based on the virtues of individualism and capitalism. They generally act aggressively in the process of negotiations, since capitalist ideology supports and reproduces the belief that “Competition is good and the best one will be the winner.” If a Turkish negotiator is not aware of fundamentals of American culture, she or he may interpret their negotiating style as rude, arrogant, opportunistic, and unethical.

Americans, when they like and respect the people they meet, call them by first names. This represents their sincerity and real friendship. In contrast, a real Londoner usually prefers to call people by their surnames. In Turkish business etiquette, when you call someone by first name immediately after you meet, if she or he does not know much about American culture, may interpret this behavior as impolite and disrespectful. In the Turkish business culture during negotiations, it is better and safer for foreigners to use formal surnames. My name is Huseyin Eskici so it is best to start by addressing me as “Mr. Eskici”. Later on, if things go well then one could shift and call me “Mr. Huseyin”. If a Turk has academic or professional titles such as “Doctor” or “Professor” it is usually best to say “Mr. Doctor” or “Mr. Professor” instead of using their first names or surnames.

Americans value time and like to start negotiation as soon as possible. They express themselves frankly and use a straightforward get-to-the-point business style. This manner may be interpreted as arrogant or disrespectful in Asiatic cultures or collectivist cultures like the Chinese and the Turks. Americans prefer to know and follow laws, rules, and regulations when they are negotiating purchasing contracts, because they are living in a strictly regulated society and they are well aware of the cost of breaching laws and regulations. Whereas tax evasion is a big crime for American citizens, in developing countries like Turkey, it may be tolerated and regarded as normal or ordinary.

![]() Describe an experience in your career that has taught you an important lesson in purchasing and describe the lesson you learned and how you have used that lesson since then.

Describe an experience in your career that has taught you an important lesson in purchasing and describe the lesson you learned and how you have used that lesson since then.

In 2007, I negotiated a supplier contract with a marketing manager who represents one of the prominent computer system companies in the world. I had to purchase additional servers and software for the system used by the Istanbul Stock Exchange to run its stock-trading operations. We had to purchase the servers from this particular company because we already were using their hardware and software to run our trading operations. They quoted us an initial purchase price of almost a million U.S. dollars.

Before the negotiation, I read all their technical documents about the system and asked our IT specialists about technical matters that I could not understand. I also asked why we had to buy the system and what were the components (hardware, software, UPS, etc.). Moreover, I learned that the marketing manager from England would personally come and negotiate the contract. After that, I did research about negotiating culture and business etiquette in England. Also, I read all the purchasing and other contracts that were signed between that company and the Istanbul Stock Exchange in order to estimate my desired target price and estimate his desired target price. From this I discovered that the discount rate from initially quoted prices with this company was typically 45 percent and the ratio of maintenance costs to purchase price was around 20 percent.

When the English marketing manager and the Turkish partner came to my office, I was ready to negotiate based on my research. After a short initial meeting, as we were drinking Turkish coffee, I told the marketing manager that I knew exactly what we needed to buy, and that I never engaged in “horse-trading” but instead worked from principles based on signed contracts already in place with his company. I told him they had to give us a larger discount on the purchase price than they had before because we would be working with them for at least 10 years, and his firm would be making more profit from the maintenance service than on the one-time sale of the system.

He told me that in order to receive a higher discount than before, his company wanted prepayment of 80 percent of the contract. I told him that we had to follow strict rules and regulations, so if they could give us a guarantee letter from an English bank, our financial department would allow us to make that prepayment. He told me that his firm could get the guarantee letter and on this basis we could negotiate the price. He told me there was no need for him to refer this issue to headquarters, because he was sure about the guarantee letter and had the authority to make a final price offer for the contract. At the end of the day we concluded the contract at a discount of slightly more than 60 percent off their initially quoted price and the ratio of maintenance service costs to the purchase price was about 24 percent.

The contract was officially ratified by the supplier and the Stock Exchange and we sent the purchase order to their sales office in England and awaited the delivery of a bank guarantee letter in order to make our prepayment. Two weeks later the marketing manager wrote me a letter stating their finance department could not get a guarantee letter from their bank and even though they could not collect 80 percent of the total contracted price before delivery of the hardware and software, they would still keep their promises about the price, discount rates, and delivery terms. They said they did not want to lose a prominent customer in Turkey and in the Mediterranean and Eurasian Zones.

What I have learned from this experience is that, if you study and prepare your negotiation strategy by taking into account a supplier's business etiquette and negotiating culture, you can make effective and efficient purchasing contracts even if the supplier has a monopoly in the business and is the exclusive seller of the product. Since then, I have continued to learn more about inter-cultural negotiation strategies. I am now writing a book in English for executive MBA students in my country. I would like to name the book Negotiation Strategies for Purchasing Specialists.

Huseyin Eskici is the Director of Administrative Affairs at the Istanbul Stock Exchange (ISE). He had served as Inspector and later as Chief Inspector in the Auditing and Inspection Board of the ISE from 1991 to 1998. He has been actively working as the Head of the Procurement Department in the ISE since 1998. He is a CPA and has an MBA degree in Contemporary Management Studies.

Purchasing

These activities are the routine activities related to issuing purchase orders for needed products. There are two types of products that a company buys: (1) direct or strategic materials that are needed to produce the products that the company sells to its customers; and (2) indirect or maintenance, repair, and operations (MRO) products that a company consumes as part of daily operations.

The mechanics of purchasing both types of products are largely the same. Purchasing decisions are made, purchase orders are issued, vendors are contacted, and orders are placed. There is a lot of data communicated in this process between the buyer and the supplier—items and quantities ordered, prices, delivery dates, delivery addresses, billing addresses, and payment terms. One of the greatest challenges of the purchasing activity is to see to it that this data communication happens in a timely manner and without error. Much of this activity is very predictable and follows well-defined routines.

Consumption Management

Effective procurement begins with an understanding of how much of what categories of products are being bought across the entire company as well as by each operating unit. There must be an understanding of how much of what kinds of products are bought from whom and at what prices.

Expected levels of consumption for different products at the various locations of a company should be set and then compared against actual consumption on a regular basis. When consumption is significantly above or below expectations, this should be brought to the attention of the appropriate parties so possible causes can be investigated and appropriate actions taken. Consumption above expectations is either a problem to be corrected or it reflects inaccurate expectations that need to be reset. Consumption below expectations may point to an opportunity that should be exploited or it also may simply reflect inaccurate expectations to begin with.

Vendor Selection

There must be an ongoing process to define the procurement capabilities needed to support the company's business plan and its operating model. This definition will provide insight into the relative importance of vendor capabilities. The value of these capabilities has to be considered in addition to simply the price of a vendor's product. The value of product quality, service levels, just-in-time delivery, and technical support can only be estimated in light of what is called for by the business plan and the company's operating model.

Once there is an understanding of the current purchasing situation and an appreciation of what a company needs to support its business plan and operating model, a search can be made for suppliers who have both the products and the service capabilities needed. As a general rule, a company seeks to narrow down the number of suppliers it does business with. This way it can leverage its purchasing power with a few suppliers and get better prices in return for purchasing higher volumes of product.

Contract Negotiation

As particular business needs arise, contracts must be negotiated with individual vendors on the preferred vendor list. This is where the specific items, prices, and service levels are worked out. The simplest negotiations are for contracts to purchase indirect products where suppliers are selected on the basis of lowest price. The most complex negotiations are for contracts to purchase direct materials that must meet exacting quality requirements and where high service levels and technical support are needed.

Increasingly, though, even negotiations for the purchase of indirect items such as office supplies and janitorial products are becoming more complicated because they fall within a company's overall business plan to gain greater efficiencies in purchasing and inventory management. Suppliers of both direct and indirect products need a common set of capabilities. Gaining greater purchasing efficiencies requires that suppliers of these products have the capabilities to set up electronic connections for purposes of receiving orders, sending delivery notifications, sending invoices, and receiving payments. Better inventory management requires that inventory levels be reduced, which often means suppliers need to make more frequent and smaller deliveries and orders must be filled accurately and completely.

All these requirements need to be negotiated in addition to the basic issues of products and prices. The negotiations must make trade-offs between the unit price of a product and all the other value-added services that are required. These other services can either be paid for by a higher margin in the unit price, by separate payments, or by some combination of the two. Performance targets must be specified and penalties and other fees defined when performance targets are not met.

Contract Management

Once contracts are in place, vendor performance against these contracts must be measured and managed. Because companies are narrowing their base of suppliers, the performance of each supplier that is chosen becomes more important. A particular supplier may be the only source of a whole category of products that a company needs, and if it is not meeting its contractual obligations, the activities that depend on those products will suffer.

A company needs the ability to track the performance of its suppliers and hold them accountable to meet the service levels they agreed to in their contracts. Just as with consumption management, people in a company need to routinely collect data about the performance of suppliers. Any supplier that consistently falls below requirements should be made aware of its shortcomings and asked to correct them.

Often the suppliers themselves should be given responsibility for tracking their own performance. They should be able to proactively take action to keep their performance up to contracted levels. An example of this is the concept of vendor-managed inventory (VMI). VMI calls for the vendor to monitor the inventory levels of its product within a customer's business. The vendor is responsible for watching usage rates and calculating EOQs. The vendor proactively ships products to the customer locations that need them and invoices the customer for those shipments under terms defined in the contract.

Credit and Collections (Source)

Procurement is the sourcing process a company uses to get the goods and services it needs. Credit and collections is the sourcing process that a company uses to get its money. The credit operation screens potential customers to make sure the company only does business with customers who will be able to pay their bills. The collections operation is what actually brings in the money that the company has earned.

Approving a sale is like making a loan for the sale amount for a length of time defined by the payment terms. Good credit management tries to fulfill customer demand for products and also minimize the amount of money tied up in receivables. This is analogous to the way good inventory management strives to meet customer demand and also minimize the amount of money tied up in inventory.

The supply chains that a company participates in are often selected on the basis of credit decisions. Much of the trust and cooperation that is possible between companies who do business together is based upon good credit ratings and timely payments of invoices. Credit decisions affect who a company will sell to and also the terms of the sale. The credit and collections function can be broken into three main categories of activity:

- Set Credit Policy

- Implement Credit and Collections Practices

- Manage Credit Risk

Set Credit Policy

Credit policy is set by senior managers in a company such as the controller, chief financial officer, treasurer, and chief executive officer. The first step in this process is to review the performance of the company's receivables. Every company has defined a set of measurements that they use to analyze their receivables, such as: days sales outstanding (DSO); percent of receivables past customer payment terms; and bad debt write-off amount as percent of sales. What are the trends? Where are there problems?

Once management has an understanding of the company's receivables situation and the trends affecting that situation, they can take the next step which is to set or change risk-acceptance criteria to respond to the state of the company's receivables. These criteria should change over time as economic and market conditions evolve. These criteria define the kinds of credit risks that the company will take with different kinds of customers and the payment terms that will be offered.

Implement Credit and Collections Practices

These activities involve putting in place and operating the procedures that will carry out and enforce the credit policies of the company. The first major activity in this category is to work with the company salespeople to approve sales to specific customers. As noted earlier, making a sale is like making a loan for the amount of the sale. Customers often buy from a company because that company extends them larger lines of credit and longer payment terms than its competitors. Credit analysis goes a long way to assure that this loan is only made to customers who will pay it off promptly as called for by the terms of the sale.

After a sale is made, people in the credit area work with customers to provide various kinds of service. They work with customers to process product returns and issue credit memos for returned products. They work with customers to resolve disputes and clear up questions by providing copies of contracts, purchase orders, and invoices.

The third major activity that is performed is collections. This is a process that starts with the ongoing maintenance of each customer's accounts payable status. Customers that have past-due accounts are contacted and payments are requested. Sometimes new payment terms and schedules are negotiated.

The collections activity also includes the work necessary to receive and process customer payments that can come in a variety of different forms. Some customers will wish to pay by electronic funds transfer (EFT). Others will use bank drafts and revolving lines of credit or purchasing cards. If customers are in other countries there are still other ways that payment can be made, such as international letters of credit.

Manage Credit Risk

The credit function works to help the company take intelligent risks that support its business plan. What may be a bad credit decision from one perspective may be a good business decision from another perspective. If a company wants to gain market share in a certain area it may make credit decisions that help it to do so. Credit people work with other people in the business to find innovative ways to lower the risk of selling to new kinds of customers.

Managing risk can be accomplished by creating credit programs that are tailored to the needs of customers in certain market segments such as high technology companies, start-up companies, construction contractors, or customers in foreign countries. Payment terms that are attractive to customers in these market segments can be devised. Credit risks can be lowered by the use of credit insurance, liens on customer assets, and government loan guarantees for exports.

For important customers and particularly large individual sales, people in the credit area work with others in the company to structure special deals just for a single customer. This increases the value that the company can provide to such a customer and can be a significant part of securing important new business.

Increasing emphasis on total cost of ownership (TCO) is bringing higher cost suppliers back to the request-for-proposal (RFP) table once again. Suppliers in the United States and other developed nations have lost business over the last two decades to lower-cost suppliers in the developing world, but now factors other than price alone are important, as companies reconsider what support they need from their supply chains. Sean Correll, a director at the strategic sourcing firm Emptoris (www.Emptoris.com), explores the trend in this executive insight.

It's no secret that the desire to acquire goods and services cheaply has led U.S. companies to begin sourcing products from countries that are considered “low cost.” Traditionally, such decisions have been made based on the monetary cost of an item or service. Not surprisingly, this left suppliers in North America, Western Europe, and other developed nations at a disadvantage, as labor costs of domestically produced goods and services could be undercut by those coming from low-cost markets.

However, during the past decade companies have begun to take advantage of the ability to make much more sophisticated decisions when it comes to sourcing the items and services they require. Strategic sourcing technology now makes it possible to analyze numerous factors simultaneously (this analysis is difficult to perform using traditional sourcing technology). This has led to a fundamental shift in the “analyzed cost” of contracting suppliers, from that of monetary cost to total cost of ownership (TCO).

TCO takes into account numerous factors beyond pure price in analyzing the cost associated with engaging a given supplier. Often these factors are qualitative as well as quantitative, and they measure factors that are critical to the bottom-line cost of doing business.

For example, in addition to price, companies may be concerned with lead or delivery times. Additionally, companies are concerned with quality, which can be measured in units such as defects per million. In fact, a recent survey sponsored by Emptoris and CFO Research Services (“Supplier Side Economics: Making Vendor Relationships an Enduring Source of Competitive Advantage,” CFO Research Services, September 2010 http://www.cfo.com/white-papers/) found that companies are now more concerned with timeliness and quality than pure price. According to the survey, senior financial executives at Fortune 1000 companies rated the two top factors with the greatest impact on their companies' business performance as the ability of suppliers to meet commitments (58 percent) and the quality of products from suppliers (54 percent). Price of products was the third factor (51 percent).

Additionally, companies tend to value the ease of doing business with a given suppler, which can be measured in factors such as the number of rejected purchase orders. All of this represents a shift in supply chain thinking with special significance for companies in the developed world that can now compete using these additional criteria.

The following example illustrates how qualitative factors are now weighed along with price in supply chain decision making:

In this sourcing event, in addition to using the monetary cost (product cost plus all logistics cost) in the analysis, we used scores based on answers to qualitative questions. One such question on a sourcing analysis performed for a Global 1000 Pharmaceutical customer was, “What percent of your warehouse facilities have been validated as being monitored for proper temperature and humidity?”

The answer could be given as any whole number from 0 to 100 (i.e., 0 percent garnered a score of 0, 1 percent garnered a score of 1, etc.)

The following formula was used to convert the score to a quantitative dollar amount:

Total Unit Cost = Price Weight × Unit Bid Cost + RFP Question Scores Weight × Unit Bid Cost × (100-RFP Question Scores Rating)/100

For our example, assume the following for a U.S. supplier:

- Total Dollar Cost of the Item = $10

- Score for question = 50

- For the analysis, 75 percent of the “analyzed cost” is obtained using the Total Dollar Cost and 25 percent is obtained using the score converted to a quantitative dollar amount using the formula above (this can be modified to any 100 percent mix, for example 80/20 or 90/10 depending on how much importance is to be placed on the Total Dollar Cost and how much importance is placed on the question score). For this item:

Total Cost = 75% × $10 + 25% × $10 × (100−50) /100 = $8.75

In theory, because of process controls (temperature and humidity) on 50 percent of the warehouse facilities, you are saving $1.25 per item ($10-8.75).

While U.S. manufacturers may not be able to compete on “unit bid cost,” oftentimes they can provide other qualitative advantages that make them more competitive.

By contrast, let's assume that a supplier from a low-cost country was able to deliver a unit price of $9, yet a Question score of 10 (i.e., 10 percent of the supplier's warehouse facilities have the required temperature and humidity controls). Using the same formula for comparison:

Total Cost = 75% × $9 + 25% × $9 × (100-10)/100 = $8.78

As you can see, in this case, the U.S. supplier is able to provide a lower cost by offering a superior “qualitative” score, despite a unit bid cost that is 10 percent higher.

Because the “Price Weight/RFP Question Scores Weight” ratio will be determined at the discretion of the commodity purchasing expert or other decision-maker based on the importance they place on it, the impact of a qualitative criterion can be diminished or expanded depending on the needs of individual purchasing companies. In this example, a 70/30 split would have yielded an even more favorable total cost for the U.S. supplier—likewise, an 80/20 split would have tipped the scales in favor of the low-cost country supplier.

Similarly, just as temperature and humidity controls were a factor in this example, companies may take into account factors such as percentage of on-time deliveries, number of defects per million, and number of rejected purchase orders.

The answer to the question of whether or not to use a higher-cost supplier or a supplier in a low-cost country will vary from case to case—there is no standard answer to such a question. However, manufacturers in developed countries can, in many cases, offer such advantages as a more optimized supply chain (which means shorter transit time and smaller warehouse space), low political and operational risk, and the ability to quickly innovate. This means that in instances where the decision maker is using advanced strategic sourcing technology, manufacturers in first-world developed nations are being considered for bids where they might not otherwise have been considered.

Sean Correll, Director of Consulting Services for Emptoris (www.emptoris.com), has worked directly with hundreds of clients to deliver solutions to their supply management organizations. He provides guidance during all phases of the sourcing lifecycle, and manages the strategic direction of projects.

Chapter Summary

The business operations that drive the supply chain can be grouped into four major categories: (1) plan; (2) source; (3) make; and (4) deliver. The business operations that comprise these categories are the day-to-day operations that determine how well the supply chain works. Companies must continually make improvements in these areas.

Planning refers to all the operations needed to plan and organize the operations in the other three categories. This includes operations such as demand forecasting, product pricing, and inventory management. Increasingly, it is these planning operations that determine the potential efficiency of the supply chain.

Sourcing includes the activities necessary to acquire the inputs to create products or services. This includes operations such as procurement and credit and collections. Both these operations have a big impact on the efficiency of a supply chain.