KEY 8

MINDFULNESS

Finding enough thinking space

It's 1854. You've just published a new book called Walden, which you feel may have a few years of shelf life in it, if that isn't too immodest. But now it's time to get back to work … in your other day jobs. As a poet. A philosopher. An abolitionist, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor and historian. Then, of course, there's your new interest in Hindu and Buddhist scriptures that speak of ‘freeing your mind’.

Imagine if Henry David Thoreau were alive today. On the Duty of Civil Disobedience would never have been written, because he would have been too focused on social media campaigns, taking down trolls and lambasting the federal government. His brain would now be far too full of the minutiae and ‘busyness’ of daily struggle to devote time to original thinking.

One thing many of us yearn for is that breathing space that would give us time to think. Whether we are the CEO, manager or solo operator of a high-performance brain, we all seem to have become too busy to give our work the amount of thinking time it deserves.

The consequence of this is that we are selling ourselves short, constraining our ideas and thoughts to the B-class seats in the auditorium of our mind. Yet the one thing that will distinguish us from the also-rans and wannabes is that ability to think carefully and deeply.

One way to achieve this is by adopting a more mindful approach. While mindfulness and different meditation practices are nothing new, their rapid uptake in the corporate world suggests there is something this practice provides us with that helps us manage our crazy busy world more effectively.

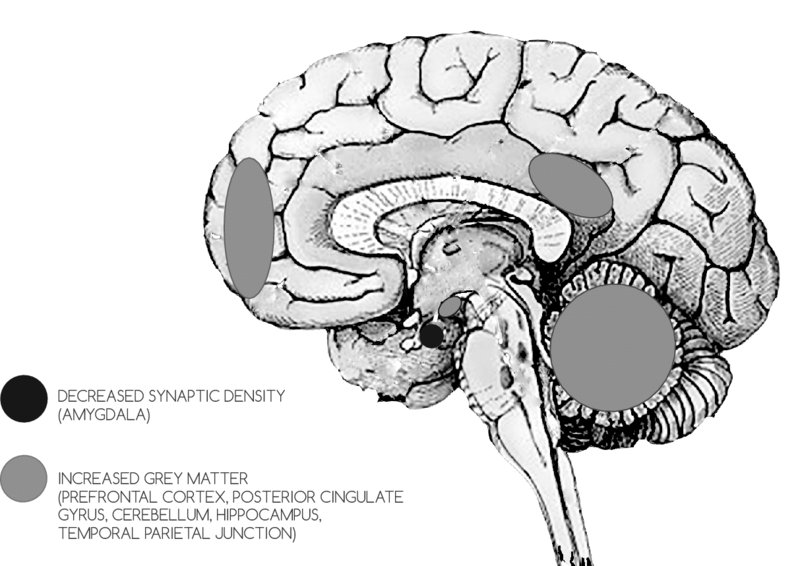

Physiological changes are seen on neuroimaging as increased thickness of the grey matter in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, and reduction in the size of the amygdala (see figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1: how mindfulness affects the brain

Operating at fast-forward

Lack of thinking time is not just a product of lack of focus. It is a consequence of our super-busy, super-productive working lives, every waking moment of which we have filled to the brim with activity.

As our technology has developed and become increasingly integrated into our lives, so has our love affair with being super-connected 24/7. The downside is that this goes against the grain of how our brain best operates.

Our brain consumes way more energy per unit of mass than the rest of our body (around 20 per cent). The forebrain, the prefrontal cortex, is especially energy hungry, so when our full focus is no longer required, our brain switches automatically to default mode to allow the mighty subconscious to get to work and reduce energy consumption.

This is what gives us the depth of understanding around a subject. It allows us to consider different possibilities and ways of looking at challenges. In other words, it opens our mind to alternatives, to new ideas and to learning.

As previously discussed, our super-busy brains are becoming cognitively a little frayed around the edges. This puts us at risk of reduced cognition and increased mental distress. The way to tackle this is to give ourselves permission to slow our brains down. This is rather like the way the Slow Food movement advocates the idea of stepping away from fast foods to reconnect with how we prepare, eat and enjoy real food so we are truly nourished.

In his book In Praise of Slow, Carl Honoré talks about how our need for speed has infiltrated everything we do, and his belief that this is detracting from our ability to be fully human.

So what would it be like to choose to dial down our daily run through life? Would that affect how we see our world? Would it influence our behaviours and choices? Would it make us happier?

The answer is yes to all the above, because we can change the way we view the world by taking a broader perspective and noticing more. By opening up our mind to alternatives and possibility thinking we keep consciously engaged with what is happening now, rather than relying on our automatic behaviours.

What's your perspective?

Our own view of the world is unique, shaped by our values, beliefs and experiences. Being aware that not everyone shares our perspective allows us to examine our own filters, our beliefs and biases, at both a conscious and a subconscious level.

Because our conscious mind processes information in a linear way, we will sometimes hold a number of ideas at the front of our mind. This can lead to a bit of a bottleneck and affect how quickly we can work through these thoughts.

While we can hold a couple of ideas simultaneously, we can only ‘see’ one image at any given moment. This is the basis of optical illusions that provide two representations of an object (see figure 8.2). We have to flick visual channels so as to ‘see’ the other and this chews up precious mental energy.

Figure 8.2: optical illusion

To maintain cognitive energy and avoid overloading the prefrontal cortex, we need to reduce the number of complex issues we contemplate at any one time.

Mindfulness over matter

Slowing down our mind and broadening our perspective is critical. One way many business leaders and others have discovered to help slow down their brains, and to find the thinking space they seek, has been through adopting a mindful approach to their lives and work.

Mindfulness has become a bit of a buzzword. It's currently all the rage, even though advocates of mindfulness (like our old friend Thoreau) have been practising it for thousands of years.

The reason for its surge in popularity is that it has been shown to be effective in reducing our levels of stress and clarifying our thinking. Some people like to use it as an attention-building tool, others as a means to rediscover a sense of inner calm. What has been especially exciting is the discovery of the effect mindfulness has on our brains, and it's all very good news.

So if you are tempted to dismiss mindfulness as just another passing fad, as a bit woo-woo and one more way to distract yourself from getting your work done, consider this.

There are now so many recognised cognitive and other benefits from practising mindfulness that we have an embarrassment of good reasons to consider trying it out for ourselves.

People who practise mindfulness have been shown to be more productive, creative, focused, clear thinking, calm, resilient, alert and energised.

In addition, the benefits to our physical health and wellbeing include lower levels of stress, better sleep patterns, and a heightened sense of wellbeing and happiness.

Mindfulness is now being introduced into the corporate world as a way to help employees manage stress levels. As our stress continues to rise like the sea levels, mindfulness has been found to provide an effective way to quieten the chattering mind and restore clarity of thinking. It helps to reduce the hyperactivity of the limbic system and dampens down the stress response.

The only thing required to become more mindful is the decision to learn how. There are a multitude of different meditation practices and no one is better than any other. It all depends on which practice you find works for you. Being curious and open to exploring different practices will help you discover which one best suits your lifestyle and temperament.

Mindfulness is the art of noticing more, especially the new things (people, events, situations and experiences) that constantly pop up in our environment. Novelty is exciting to the brain, but it can also be associated with uncertainty and suspicion. What if it's potentially dangerous and wants to hurt us?

Psychologist Ellen Langer defines mindfulness as ‘an active state of mind characterised by drawing novel distinctions’ that results in:

- being situated in the present

- being sensitive to context and perspective

- being guided not determined by rules and routine

- full immersion into engagement.

Jon Kabat Zinn, who developed the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) course in 1979, interprets mindfulness slightly differently as ‘paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgementally’.

The secret is in the neuroplastic sauce

The special sauce in mindfulness is that this and other forms of meditative practice induce neurobiological change. Novices undertaking mindfulness meditation practicing for 30 minutes each day over eight weeks have exhibited a physiological change in their brains that can be measured on MRI scans. The scans show increased cortical density and thickness of the grey matter in the prefrontal cortex, the areas associated with empathy and compassion; and in the hippocampus, the brain area associated with learning and memory (see figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3: mindfulness and neuroplasticity

What this means is that the practice leads to an increase in the number of new synaptic connections being formed. This is neuroplasticity in action.

Even two weeks of practice is enough to make a difference. In another study, novice meditators who were taught a daily 30-minute practice of compassion meditation showed measurable physiological changes in the brain and changes in behaviour after just seven hours of practice. Do you see what I see?

Of course, deciding to take up mindfulness or any other form of meditative practice remains a personal choice. You can't force anyone to learn meditation if they are resistant to the idea, but mindfulness meditation has already been introduced to address some of these problem areas, to profoundly beneficial effect.

There is a caveat though. Because mindfulness is now so popular, it has been touted as the answer to all our societal ills, which of course it is not. Nor does everyone want to use mindfulness. For those who are interested to give it a try, it can be a very useful tool to assist in managing daily life, reducing the associated stress and anxiety of always feeling ‘on’ and pushing too hard or too fast.

The best way to incorporate mindfulness in your life is to be taught correctly by an accredited meditation teacher with sufficient experience to be credible.

Live long and prosper

Meditation affects our longevity through the influence it exerts on our telomeres, structures that sit like shoelace caps on the end of our chromosomes. The telomeres were shown by Elizabeth Blackburn, joint recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 2009, to protect our chromosomes (and DNA) from degradation.

As part of the aging process, with each cell division our telomeres gradually become shorter until they reach a critical length and the cell dies. Dr Blackburn discovered the enzyme telomerase and showed how it influences the length of our telomeres (see figure 8.4). The researchers found that people who practised regular mindfulness meditation over a four- to six-month period increased the length of their telomeres by 30 per cent.

Figure 8.4: telomeres

Other recent research by Richard Davidson and others has revealed how mindfulness meditation can change gene expression through influencing inflammatory processes.

When we are stressed, our body produces higher levels of cortisol, and a number of pro-inflammatory genes, including RIPK2 and CoX2, become elevated. Mindfulness meditation in more experienced meditators down-regulates these genes, allowing a faster return to full health. The implication here is that meditation may help in preventing physical ill health. Now that has to be music to any health professional's ears, and to governments wondering how to cope with spiralling health costs.

Meditation is an easy technique to learn, there are no associated ongoing costs and the potential benefits are enormous.

Team mindful

Lack of engagement remains a thorny issue for many employers, who are racking their brains on how to re-engage their staff. Mindfulness is one component to consider including in a wellness program. Not only does each brain benefit individually, but a mindful business culture enjoys greater organisational health.

Mindfulness takes a bow

For those with a job that is enjoyable, exciting and challenging, work is a good place to be. For many people, however, their work is purely a means to pay the bills. Not all work is stimulating and interesting. Boredom stresses the brain and leads to a greater level of distractibility and mind wandering, which in certain instances can put employees at greater risk of injury.

Even highly skilled professionals can get bored. Aging pop stars play to their loyal fans, who naturally want to hear those golden oldies they know and love. But if the artists have been singing the same song for 40 years, you can imagine they are sick to death of it. Trying to make it sound fresh each time must be a challenge.

Mindfulness can play a role here. Ellen Langer did a fascinating study in which she asked symphony players who had been playing the same pieces of classical music for years to play more mindfully. She did this by encouraging some of the players to make their performance feel new in some very small and subtle way. The result? People who heard the mindful players enjoyed the performances more. Langer believes mindful attention to performance leads to greater creativity and charisma and more positive results, whatever the activity being performed.

Being mindful keeps our mind curious and solution-focused.

Johnny-come-lately

John has a habit of running late. He doesn't do it deliberately to annoy others; rather, it reflects his attention to detail and his meticulous application to staying on task until a job is done. I know this because we have been married for over 30 years. I like to get to an airport in good time for a flight; John likes to travel closer to the wire. While I stress about being late, he finishes what needs to be done and (usually) still gets to the appointed place in time. His method of working is different from mine. I could choose to get annoyed (okay … sometimes I do), or I could be more mindful about the situation and keep everyone less stressed.

So what about in your workplace? Do you have a Johnny-come-lately who is consistently the last into the room for team meetings or to turn in work or complete tasks? It's easy to become irritated by their behaviour, and to judge them as being, say, lazy, disorganised or a poor team player.

Taking a mindful approach would be more productive:

- Are they aware of the effect their tardiness has on others?

- Are they late because they are juggling too many other tasks simultaneously?

- Are they having to deal with a crisis at home such as a relationship breakdown or serious illness?

- Are they unhappy in their position, wishing they could work somewhere else?

This would allow you to explore all the possibilities with the person concerned, without judgement or preconceived answers, to facilitate a resolution of the issue.

Coming off autopilot

Mindfulness can help improve our accuracy in recording or remembering important details such as appointments and special dates. Of course using prompts in the form of sticky notes, calendar alerts or a diary can help too. In some instances, checklists are devised specifically for when a complex procedure has to be followed. But there is a caveat.

Checklists work if they are followed and, importantly, used mindfully.

Unfortunately, so much of our behaviour is automatic that we stop noticing what we are doing. For example, one weekend you are driving your car en route to a particular destination, and halfway there you realise you have taken the wrong route because your brain was on autopilot and was taking you to work. Your checklist of ‘get in car and drive to destination’ didn't include the mindful check-in to ensure you were driving to the right destination.

My husband is a pilot and is fanatical about adhering to checklists prior to any take-off and landing. Whilst he has safely taken off and landed hundreds of times, he is acutely aware that his brain is fallible. He knows the checklists play an important role in making up for this natural ‘human deficiency’ and so help keep everyone safe.

Similarly, in an operating theatre, the surgeon and team will use a series of checklists to ensure the right patient is having the correct procedure, the right side of the body is being operated on, and all instruments and swabs are accounted for.

But even the best checklists in the world can fail us if they are not used mindfully. You may hear the instruction and respond ‘Check’ because you have heard it a thousand times before, but did you remember to actually flick the switch?

Practice makes peaceful

The essence of freeing your mind from busyness, and giving it room to think, is to make a start — and that involves choosing which form of meditation practice is best for you. The answer is ‘the one you like and that best fits your lifestyle’.

Different forms of meditation practice do produce subtle differences in brain outcomes. If focus is your thing, then mindfulness might be the one to try. If your empathy and relatedness need a boost, loving kindness or compassion meditations would be good to try.

It's called a practice because it is practised regularly like a musical instrument, ideally every day. Richard Davidson suggests sprinkling several two- to three-minute meditation practices across your day.

Mindfulness, in my mind, produces a ripple effect. My formal daily mindfulness practice then leads to a more mindful approach to other daily activities such as eating, exercising and interacting with others.

How long should you practice?

As long as the time you have available. Whether it is 50 minutes or five, what matters is putting in the practice in some form, preferably every day.

That five minutes is still enough. As with many other brain-enhancing activities, it is through repeated practice over a period of time that we get the maximum benefit. Make it a regular practice and it quickly becomes a daily habit. While it's a good idea to practise daily, missing an occasional day doesn't matter.

How do I do this?

When first starting out, it's a good idea to choose a place you can use regularly, somewhere you come to associate with the practice. But of course you can do it anywhere, from a quiet room in your house where the sunlight first enters in the morning, to a park, a mountaintop, a café, even a supermarket queue.

At the start it is probably worth joining a class to help you get into the habit of doing your practice. A class keeps you accountable and you get to meet lots of like-minded people. Classes are typically held weekly over eight weeks, and you can expect to be given homework!

Tuning in to your body and learning how to quieten your mind can be a challenge, especially if you are used to working at a frantic pace. This is where the body scan meditation or some deep breathing exercises can help you feel more relaxed and in tune with your bodily sensations.

The following suggestions for using breathing exercises to aid relaxation could easily be incorporated into your workday. As a manager, team leader or executive, encouraging your staff to participate in some form of regular relaxation practice can be highly beneficial, as it promotes calm, focused thinking and results in a happier, more productive workplace.

This could take the form of a 15- to 20-minute relaxation session at the beginning of the workday or after lunch. Some employers might balk at the prospect of the ‘interruption’ caused by a staff relaxation session or power nap, but in terms of increased productivity, that 15 minutes of relaxation, meditation or naptime could result in another two to three hours of efficient, high-quality work.

Focus on the breath

If using a floor rug, lie on your back, allow your feet to fall apart, your arms to relax at your sides, palms upturned, and gently close your eyes. If sitting, choose a chair in which you can comfortably place your feet flat on the floor, and tuck your back into the chair so you are not slouched or leaning but sitting upright, as though a cord is gently pulling your head upward. Place your hands in your lap so your arms are relaxed and comfortable, and either gently close your eyes or adopt a soft gaze looking down.

Now focus on your breath. Notice the passage of the air as it enters and leaves your body, the rising and falling of your chest and the contact of your body with the floor or the chair. If you notice your mind wandering off into thoughts or ideas or places (and that does happen, repeatedly!) just acknowledge this and each time gently bring your focus back to your breath.

Mindfulness is not about ‘emptying’ your mind or falling asleep; it is a mental discipline of focusing on one thing — your breathing — to keep in the here-and-now, the present moment. What happens is that because you are thinking about what is going on right now, you stop thinking about the future or your past; you remain engaged with the present. This skill, built up over time, makes it easier for you to stay on task and to manage your distractions more effectively, more mindfully.

Mindful leadership

Mindfulness is now well established in the corporate world. Since Chade-Meng Tan, Chief Happiness Officer at Google, introduced his Search Inside Yourself program in 2007, many other companies have introduced mindfulness programs, including Aetna, The Huffington Post, General Mills, Apple, Medtronic and Goldman Sachs. Companies are funding these programs for their staff and setting up meditation rooms.

Why? Because they have found that offering meditation classes to employees as part of a workplace wellness program can:

- increase productivity

- reduce stress-related illness

- reduce absenteeism

- reduce the incidence of mistakes and errors

- improve recall and memory.

CEOs and leaders such as Ray Dalio, Bill Clinton, Rupert Murdoch, Mark Benioff and the late Steve Jobs have all practiced mindfulness as a way to help them manage their leadership positions more effectively.

Meditation and mindfulness apps such as Headspace encourage people to take 10 minutes out of their day to help improve their health and wellbeing. While mindfulness is commonly used to boost efficiency and productivity, its impact on elevating health and wellbeing cannot be underestimated. A healthy workforce is a happier workforce, which naturally translates into greater engagement, motivation and fulfilment.

Leaders must have the thinking space to pause and reflect. Our current practice of operating continuously at full pelt denies the brain the opportunity to do what it does best — assimilate facts, find new associations and determine the best course of action.

The practice of introspection, using mindfulness or whatever meditation method we find helpful, makes it easier for us to stay connected to what really matters and to let go of the unimportant. As Daniel Goleman, author of Primal Leadership, wrote recently, ‘a primary task of leadership is to direct attention. To do so leaders must learn to focus on their own attention … Every leader needs to cultivate the triad of awareness of self, others and the wider world’.

In a world where the pace is continuing to gather momentum, mindfulness offers a means to regain control of our thinking and, by reducing stress, to re-engage with our work and lives in a more meaningful way.