chapter 11

creating weakness

In the many focus groups I've been involved in, not once has a participant said, ‘I want the shopping experience to be more difficult, and I want the product to be more complicated to use'. I'm pretty sure no-one at an IKEA focus group said, ‘Make it harder for me'. As outlined in chapter 5, IKEA places several barriers in a consumer's path, but it remains one of the most successful companies in the world. Paradoxically, the irritating shopping experience and need to construct the furniture yourself mean consumers value the brand more highly. This chapter builds on the ideas outlined in chapter 10 and offers practical ways to make brands more sticky in the mind of consumers through creating weakness. You can:

- force friction

- be wasteful

- make mistakes

- make a mess.

This chapter builds on the ideas outlined in chapter 10 (so if you are skipping chapters, read the last one before you read this one) and offers practical ways to make brands more sticky in the mind of consumers by creating weakness.

1. Force friction

‘What's different here?'

As we glide through the day, most of us operate on autopilot (or System 1 thinking, as discussed in chapter 3). This is especially the case with people glued to their phones. So how do you make people pay attention if they're about to encounter something dangerous, such as a railway line? New Zealand rail company KiwiRail faces this issue every day. In New Zealand there are several urban level crossings, which means pedestrians walk across rail lines. Reports from train drivers and CCTV footage revealed many pedestrians weren't paying attention and were placing themselves at risk. Some pedestrians crossed as the alarms still rang, walking after one train had passed but without knowing if another train was coming in the opposite direction. Many people wore headphones or had their faces buried in their phones. KiwiRail needed to find a way to get people to pay attention when they approached the railway.

During Rail Safety Week in 2016, the Conscious Crossing experiment took place. KiwiRail and advertising agency Clemenger BBDO used the insight that the more familiar you are with an environment, the harder it is to get your attention. It decided to create a continually changing environment by installing movable rail fences on either side of the rail line. But the fence configuration was frequently changed. Sometimes there was a zigzag path, other times it was an S shape. Each day pedestrians were forced to take a different route through the crossing. It's very clever.1

Forcing people to think is often more desirable than making it easy for them not to think.

What will it take to make you stop?

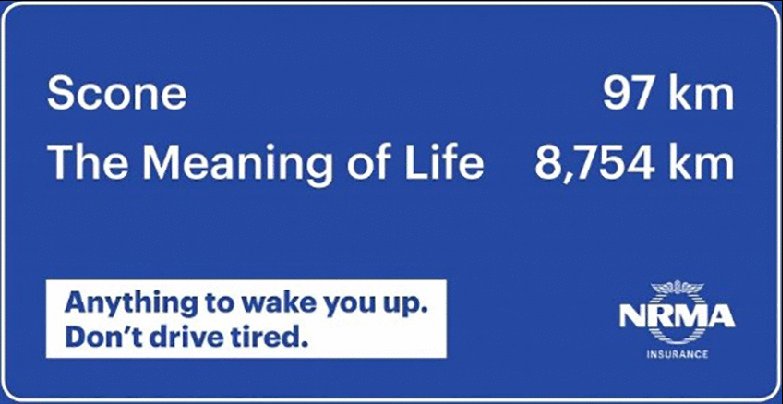

If you ask drivers who've been on the road for some time to ‘Please stop and take a break', some will, but many will not. NRMA Insurance asked for advice for a campaign to run during Easter 2019. What would it take to convince drivers to pull into a ‘Driver Reviver' site and recharge before returning to the road? I'm sure you've driven past many on long-distance trips. NRMA Insurance wanted drivers to interrupt their desire to continue driving, pull over and have a break.

- We commissioned market research agency YouGov Galaxy to find out why people don't stop at Driver Reviver sites. Four in five Australians admit they ignore advice to stop every two hours, saying they want to arrive at their destination as soon as possible. We hoped this research would shine a light on the issue.

- NRMA Insurance created outdoor advertising with the line ‘What will it take to make you stop?' Each included unexpected, attention-getting lines such as the one shown in figure 11.1.

- Selected Driver Reviver sites had kooky offerings to lure drivers to pull over and take a break. They included:

- the chance to play ping pong with tennis legend Pat Cash (see figure 11.2, overleaf)

- people dressed as giant kangaroos handing out chocolate

- Elvis impersonators singing by the side of the road

- edible insects offered to drivers.

Figure 11.1: NRMA sign

Figure 11.2: Pat Cash at a Driver Reviver site

This encouraged people to break from their System 1 mindset long enough to judge if they should continue driving or take a break. And the good news is many did take a break. The number of cars that visited the sites increased by 73 per cent. The campaign was covered in the media 162 times, including the evening news.

Someone is watching you

Water conservation is an ongoing issue in Australia, particularly with climate change. During the Millennium Drought, water levels in Melbourne dams reached an all-time low, and the Victorian government introduced the ‘Target 155' program. This encouraged residents to restrict their water consumption to 155 litres per person per day. Suggestions included using a four-minute egg timer while showering, collecting cold water in a bucket before the water becomes hot, and to turn the tap off while brushing your teeth. The campaign was successful, with many individuals and businesses changing their behaviour. And, most importantly, water usage dropped. Many households even replaced their grass lawn with artificial lawn.

In 2018, Melbourne's largest water provider, Yarra Valley Water, asked my agency for advice on how to get people to conserve water. But there was no explicit hook to hang a campaign on. There was no new legislation restricting water use. And there was an added difficulty that, because most water use happens in the home, it's harder to influence behaviour. We looked at previous campaigns. Successful programs were generally associated with water-saving reminders inside the house, such as egg timers or blue digital shower timers. According to research,2 such devices are more successful than broadcast advertising in changing behaviour. So this was an excellent place to start.

Research company Nature confirmed the bulk of water usage now happens inside rather than outside the home. The ‘tut tut' look of a neighbour as you furtively water the lawn on a non-watering day is absent inside the home. How could we create an object that wouldn't be ignored, and that watches how much water you use? Marketing sciences suggests those most likely to ‘listen' to the objects are children. But we had to devise a system that would appeal to everyone in the household. It had to be like The Simpsons and speak to all ages and stages. Psychologists have studied so-called ‘watching eyes' and found people are more compliant and law-abiding if they think someone is watching them.3

Using these insights, we created ‘The Water Watchers'. These are a range of tiny silicon figures that are placed in the shower and near other taps in the home to remind people to use less water. It's currently being trialled in Melbourne.

I'm writing about it here because it's a great example of creating forced friction and breaking habits. The little Water Watchers will act as a roadblock to people's habitual and unthinking use of water. Much like the NRMA Insurance example, and the Conscious Crossing, it forces them to think about and reconsider their behaviour.

2. Be wasteful

In advertising, it's the waste that has an impact.4 This means the communications we deem to be waste because we can't attribute where a message lands may connect with infrequent buyers. The authors of a study on this, also discussed in chapter 3, make the same point about high production values in advertising. If an ad appears to be expensive, it's more likely to be trusted because it's from a business that has committed to spending resources. The foyers in bank buildings in the Victorian era were richly decorated with marble and panelled wood. Consumers felt they could trust the bank because it had resources to burn on frivolous things like a beautiful foyer. (Recall the examples in chapter 3 of the peacocks and fat older men who drive Ferraris to imply abundant resources to waste on silly things.)

Convince consumers your message is important by being wasteful. I always think of those working in public health when I talk about this principle. Have you had an appointment with a physiotherapist who gives you a photocopied piece of paper with exercises you need to do? Do you ever do those exercises? What if they were photocopied on quality paper or in a fancy book? You might take the instruction to exercise more seriously. The notes themselves, and not just the content, would feel important and worth following up.

A perfect marketing example is naming rights for sports stadiums. When Aussie Home Loans started making waves in the home loan market, it asserted itself as a credible player by acquiring naming rights for the Sydney Football Stadium. From 2002 to 2007, the stadium was named Aussie Stadium. The message implied they were a market player because they were big enough and profitable enough to name a stadium. Sunk costs demonstrate confidence and commitment, and if it attracts attention, consumers often follow.

Another example of waste being effective is search engines retrieving results for the user. Professor Michael Norton has studied the importance of installing counters so people can observe how many options the algorithm is working through before finding the perfect match.5 A visual representation of what the search engine is doing, rather than instantly finding the best option, increases user satisfaction.

3. Make mistakes

Earlier I mentioned the ‘pratfall effect' in which people who make small mistakes are perceived as more likable. Think of someone who accidentally spills a cup of coffee. If they are otherwise competent, this mistake makes them more likable. It turns out the ‘pratfall effect' applies to people and brands, and to robots as well. A 2017 study by the University of Salzburg found people prefer to interact with imperfect rather than perfect robots. They could relate to a robot that makes a mistake and learns from the mistake, in a similar way to human learning. The robot's mistakes were identified but it was still rated as more likable than the robot that performed the task perfectly. It's believed robot designers are now incorporating flaws into robot design. Researcher Nicole Mirnig said, ‘… instances of interaction could be useful to further refine the quality of human-robotic interaction … a robot that understands that there is a problem in the interaction by correctly interpreting the user's social signals, could let the user know that it understands the problem and actively apply error recovery strategies.'

Don't be afraid to step into the dark from time to time, and make mistakes, or at the very least create incongruencies. Many brand taglines, logos and headlines have grammatical errors in them, from McDonald's ‘I'm lovin' it' to KFC's ‘Finger lickin' good'. And many of the classic images in advertising don't make sense, from a meerkat in a dressing gown to a gorilla banging the drums.

The brain loves a visual puzzle or incongruity, or identifying when something is not quite right. We are wired to notice if something is out of place or doesn't quite fit thanks to the evolution of the attention system of the human brain. Marketers can take advantage of this information by deliberately making mistakes. If your ad is messy or incomplete, a consumer will spend more time processing the information or messaging. You can, in being messy, direct a consumer's attention to spend more time with a brand. Have you spent more time than you should detecting differences in two near-identical pictures? It's the same principle. We enjoy identifying and rectifying mistakes. Global eyewear brand Specsavers employed this strategy in their ‘Specsavers spot the mistakes' advertisement. The ad featured a man renovating his daughter's cubby house, only to realise that he had renovated the family dog's kennel. There were 15 mistakes embedded in the ad, with viewers invited to spot the errors and go in the running for a weekly $1000 prize.

Minor mistakes in a product can increase its desirability and intent to purchase. In behavioural economics, this is referred to as ‘blemishing'.6 Research suggests desirability for a brand increases when the brand is presented as slightly imperfect. This included wine glasses, hiking books and chocolate. The same principle applies to restaurant reviews. People are more attracted to a restaurant if there's a hurdle, such as terrible parking, because they believe the restaurant must be fantastic to overcome these negatives. In addition, references to the difficulties of parking make the reviews appear more authentic. Here are two examples of the blemishing principle in action.

There are twigs in Monteith's cider

Monteith's is a New Zealand brewing company that wanted buyers to know its cider is made with fresh fruit. How did they quickly establish their credentials? They shoved some twigs into the packaging of their crushed apple cider and crushed pear cider. After several people contacted the company, it issued an ‘apology' saying the twigs are a by-product of making cider with fresh fruit. Consumers were welcome to use other brands made from concentrate, with no twigs in sight. The promotional twig campaign saw sales increase by 32 per cent.

The labels won't stick

In the year 2000, Howard Cearns, Nic Trimboli and Phil Sexton founded the brewery Little Creatures, creating a wonderful award-winning beer. Over long, hot summer days, I'd store Little Creatures beers in an esky. After a while, the label would start to peel away from the bottle. By the end of the day, most of the labels would be off completely, and you were left drinking beer from a plain brown bottle. This was a known issue for the brand, with many people complaining about it. Nothing was done about the labels for many years.

When I asked Howard about the slippery labels, I expected him to tell me it was a deliberate ploy to give a unique, hand-crafted feel to the beer. The real reason was slightly different. Howard said,

The bottles had to be sourced in small parcels from places like Portugal because Australian manufacturers only did large-scale runs and Fosters wasn't going to allow us to use the VB bottle any time soon. The imported bottles had difficult surfaces requiring unique change parts. There was too much moisture as they came through the new labeller, causing havoc. You are forgiven for a while, but then you have to make them stick.

This imperfection was because of a scrappy, resourceful approach. The non-sticking labels, although a fault, became a signifier of a better-quality beer. Howard then spoke about his latest venture, craft vodka. ‘We recently bottled our first batch of craft vodka out of the Hippocampus Distillery and guess what? The neck labels don't stick properly. You have to smile.' And smile he will, because again the imperfect labels will signify a more bespoke product.

Little Creatures has since been bought out by Lion Nathan and it has fixed the issues with the labels. They won't peel off if left in an esky of melting ice all day. And in fixing the labels, they've arguably compromised the authenticity of the brand a little.

4. Make a mess

Think of the best online brands in the world, and now think of their user experience. I think Facebook has one of the worst user experiences. Not only that, but the company continually changes its rules and users have to adjust. I'm not sure if this is deliberate, but it doesn't feel particularly consumer-obsessed or consumer-focused. And yet the brand is successful. If consumers say they want a seamless experience with your brand, don't believe them. Or better yet, believe them, but don't give them what they say they want. Instead, hunt for opportunities to cause confusion, make mistakes or be wasteful.

The flip side of fluency

When I was in New York for business, I met with Adam Alter, a very smooth and free-flowing young chap. He's an associate professor of Marketing at the Stern School of Business, which is a part of New York University. Adam's book Drunk Tank Pink was a New York Times bestseller and an exploratory book on the power of behavioural economics. Like me, he has a background in marketing and psychology and has effortlessly (it seems) become an opinion leader in the world of ‘fluency'. Adam became interested in the topic of cognitive fluency when studying for his PhD with supervisor, Danny Oppenheimer. I reference Danny in my book The Advertising Effect: How to change behaviour.

Adam rose to global prominence when interviewed for an article in the Boston Globe titled ‘Easy = True: How cognitive fluency shapes what we believe, how we invest, and who will become a supermodel'. I highly recommend the article and Adam's book.

Adam describes the concept of cognitive fluency as

the ease or difficulty you experience when making sense of a piece of information. For example, this sentence is fluent: ‘The cat sat on the mat.' And this one means the same thing, but is more disfluent, or difficult to process: ‘The mat was sat on by the cat.' You can manipulate fluency by choosing clear (fluent) or ornate (disfluent) fonts, by adjusting the contrast between the foreground and background in an image or piece of text, by choosing long or short words and using many other approaches.

People prefer fluency to disfluency; some of Adam's work has even shown that having a fluent name helps lawyers ‘become partners at law firms more quickly' than lawyers whose names are disfluent, and that stocks starting out on the market do better if they have simple names. I think the name ‘Adam Alter' has a high degree of fluency, and he is a well-known thinker on the subject. (I didn't ask him if he might not be as famous if his name didn't have alliteration for fear of being a bit of a shit.)

Cognitive fluency is related to many ideas described in behavioural economics. It's perhaps best explained using Daniel Kahneman's System 1 and System 2 thinking, discussed in chapter 3.

German radiologist Christine Born examined what happened in people's brains when they looked at various brands while in an MRI machine. The study revealed brains respond better to strong brands.

The results showed that strong brands activated a network of cortical areas and areas involved in positive emotional processing and associated with self-identification and rewards. The activation pattern was independent of the category of the product or the service being offered. Furthermore, strong brands were processed with less effort on the part of the brain. Weak brands showed higher levels of activation in areas of working memory and negative emotional response.7

So, all good. Create a sense of cognitive fluency and people will choose your brand over another. But what if your competitors are already doing this? How do you stop or interrupt the cognitive flow and get people to consider your brand next to your most established competition?

As Adam puts it, the power of disfluency can be summed up in this way:

People spend only as much mental energy as they need (and no more) to reach an adequate solution. You can encourage people to spend more energy by making the task seem more complicated or by making them feel less confident in their responses. One way to do this is to make the experience more disfluent. For example, if you print a question in a font that's hard to read, it seems harder to answer, even though the question itself hasn't changed. There's some evidence that people spend more time and energy solving problems that are printed in the harder-to-read font.

Creating disfluent brand experiences means more extended processing, so people sit with them for longer. Adam mentioned a study from the University of Michigan.8 They asked people this seemingly simple question: ‘How many animals of each kind did Moses take on the Ark? Most people answer with ‘two'. But it was Noah, not Moses, who was on the Ark. However, it was easier to say ‘two' rather than stop and pay attention to every word in the question. Our brains take a few words and fill in the blanks for us. We're not expecting to see an error in the question, so we ignore it. We create cognitive fluency. This is excellent news for brand Moses but not for brand Noah.

Yet the researchers found that people would question the statement a little more if it was written in an ugly and difficult-to-read font. In this instance, there was a low level of processing fluency and this, as predicted, led to more people detecting the misleading nature of the question, and identifying the correct answer as ‘zero'. In making people use more effort to process the information, Noah is recognised as the mastermind. Participants were less likely to rely on spontaneous association when the font was difficult to read. If you want people to pay attention and break ‘cognitive fluency' flow, make your audience work a little harder. If your brand isn't number one in a category, remember this. Make people think or they may not think of you.

In marketing, the category leader will (almost by definition) be the brand that most benefits from any misattribution. Whenever anyone advertises in a particular category, people may remember the ad but incorrectly attribute it to a brand that wasn't advertising. The market leader invariably has more customer loyalty, higher penetration and more overall users, so more people associate anything to do with the category with that particular brand.

Brands that aren't the market leader — challenger brands — have to be noticed and cut through. These brands also have to ensure that anything the brand does is attributed to that brand. A possible solution to this problem is cognitive disfluency. Make people work harder to process information about your brand. They'll code it more deeply, remember it for longer and realise it was you and not the competitor talking to them.

But Adam cautions about making people work too hard, recommending disfluency be used sparingly and judiciously; if a message is too difficult to decode, people will just disengage.

Don't forget this

My previous agency, Naked Communications, did very well at the 2019 Cannes Lions, the pinnacle of advertising creativity. There was a lot of interest in its project with RMIT University that created a new font to help students retain important information. Called ‘Sans Forgetica', the font was constructed using the principle of ‘desirable difficulty'. The font is harder to process than other fonts because bits of each letter are missing. This additional layer of difficulty means readers have to work harder to process the font and, as a result, their memory of the content improves. The font has been downloaded more than 300 000 times, and the team at RMIT believes it could help in learning languages and for those with Alzheimer's disease.9

![]()

This chapter has loads of mistakes in it, as does the rest of book, I'm sure. I did it as a deliberate ploy so you would remember my favourite marketing tactics designed to get consumers to see and stick with your brand.

Notes

- 1 Tracksafe Foundation NZ. (2016). ‘The conscious crossing'. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T_DZPdOhjNM

- 2 Syme, G. et al. (2000). ‘The evaluation of information campaigns to promote voluntary household water conservation'. Evaluation Review, vol. 24, pp. 539–578; Smart Water Fund. (2006). ‘Development and trial of smart shower meter demonstration prototypes'. Project Smart1. InvetechPty Ltd.

- 3 Van Der Linden, S. (2011). ‘How the illusion of being observed can make you a better person'. Scientific American. http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20140209-being-watched-why-thats-good

- 4 Ambler, T., & Hollier, E.A. (2004). ‘The waste in advertising is the part that works'. Journal of Advertising Research, vol. 44, iss. 4, pp. 375–389.

- 5 Buell, R.W., & Norton, M.I. (2011). ‘The labor illusion: how operational transparency increases perceived value'. Management Science, vol. 57, iss. 9, pp. 1564–1579.

- 6 Shiv, B., Danit, E., & Zakary, L.T. (2012). ‘When blemishing leads to blossoming: the positive effect of negative information'. Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 38, iss. 5.

- 7 ScienceDaily. (2006). ‘MRI shows brains respond better to name brands'. Radiological Society of North America. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/11/061128083022.htm

- 8 Song, H., & Schwarz, N. (2008). ‘Fluency and the detection of misleading questions: low processing fluency attenuates the Moses Illusion'. Social Cognition, vol. 26, pp. 791–799.

- 9 RMIT University. (2018). ‘Sans Forgetica. The font to remember'. https://www.rmit.edu.au/media-objects/multimedia/video/eve/marketing/sans-forgetica-the-font-to-remember