chapter 1

stop the consumer obsession

Businesses are currently obsessed with customers, consumer journey mapping and human-centred design. I believe your focus should be elsewhere: on understanding, defining and disseminating your brand throughout your organisation and to consumers. Prioritising the consumer over the brand erodes brand value and sets it on the path of homogenisation. Your brand will become just like the others. As you read this book, be open to the message to stop listening to the consumer and, instead, start to hear your brand.

Why do all cars look the same?

I recently bought a new car. During the protracted search, I became more and more confused as the brands, features, appearance and styles merged into one other. We wanted a family car with a bit of personality. This pretty low bar soon became a high bar. When I was a kid, I remember feeling proud as punch when my parents bought a Datsun 120Y. This was a car with power and grunt. And it was a radical shift from our previous car, a Fiat, which was seen as very exotic and European, particularly in Australia at the time. As a kid, I was into cars. Compared with today, the car back then had so much more character and functional differences.

But in the years that followed, something happened. Through globalisation and a flattening of consumer tastes, most cars are pretty much the same. Even car engines for different branded vehicles are made in the same factory. For example, the Volkswagen Golf GTI has the same engine as the Skoda Octavia RS. The Mercedes-Benz A180d has a dCi Renault diesel engine, which is also used by Nissan. It's the same story with the chassis, with similar frames rolling off the same lines for different brands.

Convergence isn't only happening with cars. Most products in the shops are similar. Cereal, tinned tomatoes and shampoo are similar. Branded and home-brand tortillas are often made by the same manufacturer with very little, if any, difference. Beer is similar. Insurance is similar. If you make an inquiry about your superannuation fund, the customer support services are often shared by several funds. At a functional level, brands are similar (if not exactly the same). Brands and businesses have become homogenised and it's a challenge for marketers to differentiate them.

The problem is more pronounced the more established the category, and the more established the brand is in that category. Take, for example, the Big Four banks in Australia. Most bank accounts are similar. The interest rate may vary slightly, but the offering is essentially the same whether you bank with Westpac, ANZ, Commonwealth or the NAB. Apart from the different-coloured logos (two of which use red), there's hardly any differentiation between them. But it wasn't always like this. Even banks once had distinctive and differentiated positions in the marketplace.

In addition to homogenisation, something else is happening. The fun bits of a car have disappeared. My wealthy uncle was a bit of a car fanatic, and I remember riding in a variety of them with him. Each was shaped differently, with unconventional design elements. Muscle cars of the 1970s had exaggerated bonnets. There were large tail fins on so-called ‘Yank tanks'. The lime-green Porsche in the 1980s had a whale tail. You don't see these flourishes in car design any more. It's all so … practical.

It's a similar story with architecture. In the foyers of banks from the Victorian era, wealth and opulence exuded from every corner, with elaborate cornices, ornate marble pillars and panelled wood walls. Or walk down a street of an inner-city suburb with houses from Victorian and even Georgian times: there are detailed flourishes and finishes everywhere. In the 1950s, it was common to have big curved walls within living spaces. Many of these design elements were not practical — they were artistic. Whereas buildings constructed today tend to all look the same as each other. The art and aesthetic has been removed. Buildings designed by architects who break away from the norm, such as Frank Gehry or Zaha Hadid, stand out because they are distinctive, with a vision that withstands practicalities, committees and possibly focus groups.

I see the same homogenisation process at play in politics: Australia's mainstream politicians lack vision. They are interchangeable middle-of-the-road people with interchangeable ideas. True, US President Donald Trump isn't from that mould, but I think he's an aberration. Politicians today are obsessed with polling and focus groups. In Australia, parties ditch leaders when they fail to win polls. Not election polls, but Newspoll, even though it got it very wrong in the 2019 federal election. Politicians seem to lead by consensus, not vision.

Let's apply this logic to my world of advertising and brands. These days, it can be a tough slog. In days gone by, advertising focused on entertainment and the creation of big responses. There were boundary-pushing themes (progressive and conservative) and campaigns were either so shocking, scary, charming or weird they were bound to get attention. This is mostly missing in the industry today.

It's not only advertising that's afflicted. The grit, beauty, romance or weirdness of pop culture has been shaved or chopped off in this sanitised, efficient and practical world. I believe the main reason this is happening is because of advertising's reliance on focus groups. Well, not focus groups alone; but I think there's an over-reliance on people's opinions at the expense of creating a vision and sticking with it.

Love him or loathe him, Steve Jobs had vision

Deft alignment is needed to make your business or organisation stand apart from the pack. In 1997, when Steve Jobs returned as CEO of Apple after 12 years away from the company, he told staff:

This is a very complicated world, it's a very noisy world. And we're not going to get the chance to get people to remember much about us. No company is. So, we have to be really clear about what we want them to know about us.

I'll repeat the important part: ‘So, we have to be really clear about what we want them to know about us.' I love this. Jobs knew Apple had to fight against conformity and make the brand different from others in the personal computer market. Ensuring your brand is different and distinctive in the minds of consumers is difficult and takes enormous effort. The entire organisation needs to align behind this understanding and what the brand is aiming to achieve. Steve Jobs was amazing at instilling this within Apple.

‘Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything.' This is how Steve Jobs introduced the era-defining iPhone in 2007. And he wasn't wrong. In addition to its brilliant technology, Apple was smart in its naming protocol. It didn't come up with a complicated technical name for the new phone. As Mat Baxter, a friend and global CEO of media agency Initiative observed,

… the ability of Apple to use product names and language that was less technical and more human than its competitors' was a key differentiator, and proof point of its ‘Think Different' brand positioning.

But something changed in 2017. The tenth-anniversary iteration of iPhone was named iPhone X. But consumers were confused. They called it the letter ‘X' rather than Roman numeral ten. Mat is obsessed with technology companies and a keen observer of their fortunes. When Apple broke its naming convention, he was mortified and wrote an article on LinkedIn saying,

Of course, product naming blunders can be forgiven. Perhaps someone in marketing felt the ‘X' made the iPhone 10 feel appropriately special for its anniversary year. Or maybe it just looked better as an ‘X' on the packaging and marketing materials. Whatever the reason, Apple had every opportunity to reset and get back on course with its famously simple and non-technical product names. Oh boy, did they stuff that up.1

Mat suggests this small stuff-up is a signifier that Apple is becoming just like other technology companies. It has lost one of its points of differentiation — its naming convention. If Apple doesn't get its brand, what hope is there for the rest of us? For so long, Apple and Virgin, the world's consumer champions, have been held up as the benchmark of strong brands. But even great brands stray off course if not tightly and holistically managed. Apple's shift away from its previous naming convention was detrimental to the brand, and an indication the company is losing its way.

It's challenging to keep brands on course. The irony is the more you use the consumer as your rudder, and the more you ask them what they want, the easier it is to be thrown off course. You can end up creating something generic, vanilla and missing the interesting bits.

The customer is not the answer. Most of the time, the consumer doesn't even know what they want. As Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company, is reputed to have said, ‘If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.' The more you listen to the consumer, the more your business or brand is in peril. And I predict that if you hear me out, you'll agree with me.

Customer obsession

Before I speak at conferences, I'm given a briefing. It's a real eye-opener as, over the course of an hour or so, I quickly learn about a business and then leave. The briefing is rarely conducted by someone in marketing; usually it's someone organising the event or from internal culture or human resources. The briefings usually consist of me getting up to speed as quickly as possible on the business, the brand, its internal culture, key business challenges and opportunities, and the company's values. This rapid-fire induction within many companies puts me in the privileged position of gaining a deep insight.

One thing that often strikes me is how early the customer is mentioned. The challenge for many of the businesses I speak at is their desperation to ‘get closer to the customer' and ‘better understand the customer'. The phrases I hear over and over again are ‘our business is customer-obsessed', or ‘customer obsession is one of our values'. The other issue is people changing ‘marketing' to ‘consumer' or ‘customer'. Marketers around the world are changing their work titles to Chief Customer Officer or Chief Audience Officer or Chief Consumer Officer. There are books promising tips and tricks on how to become customer-obsessed. No-one has changed their work title to be the Chief Brand Officer or created a central organising value that says ‘be brand first'.

Marketing has always been about understanding your brand and your consumer and how they match up. But when I heard the term ‘customer-obsessed' one too many times, I started thinking about why, and how widespread it is. This observation at speaking gigs wasn't the only reason for my concern. This is how global consultancy Accenture Interactive describes the role of the emerging Chief Marketing Officer (CMO):

They're making the customer central to their thinking and vision not just in the services they provide but also in how they adapt. They're building a customer-obsessed organisation, rewired from the inside-out with new technologies, new customer expectations and a new accelerated pace for change.2

There's no mention of brand, marketing, demand or growth — only the customer. Further, they recommend ‘Re-orientating and re-invigorating your organisation around the customer. Deliver hyper-relevant customer experiences at every touchpoint, building agility into the organisation to evolve to the changing needs of the customer.'3

This is a clear example, I believe, of getting things wrong. Customer obsession is not creating breakthrough thinking, nor is it creating stronger brands. It's inadvertently creating bland not brand-driven organisations. The recommendations of Accenture Interactive put way too much focus on listening to the consumer, and not on hearing your brand.

Some numbers behind customer obsession

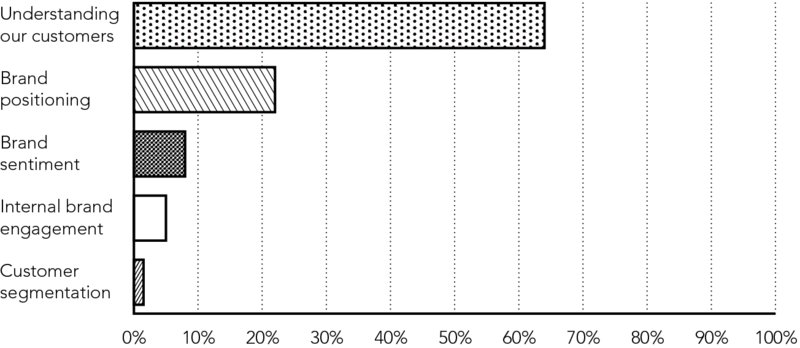

After observing that brands are too customer-obsessed, I set out to discover why the old balance between understanding the brand and understanding the customer is now out of whack. In becoming customer-obsessed, many companies are losing the ability to remain brand-obsessed. To test the hypothesis, and better understand the issue, I asked marketers from around the world to complete a comprehensive survey about their behaviours with brand building and customer understanding. The survey was a self-reported questionnaire asking how they focus their time, effort and money when doing the job of marketing. From these behaviours, I could ascertain if customer obsession was taking hold and if brand obsession was suffering. Eighty-eight marketers completed the survey. Figure 1.1 got my attention.

Figure 1.1: desired time and resource allocations of marketers

When asked if there was one thing they wanted to focus on and better understand, 62 per cent said ‘understanding our customers', with only 22 per cent seeking to understand their brand. The dominance of consumer understanding at the expense of brand understanding was evident throughout the survey. In terms of dollars spent on understanding the brand versus the consumer, 22 per cent of respondents admitted to spending $0 last year in understanding the brand, while only 12 per cent spent $0 understanding the customer. Further, 72 per cent of respondents said it's ‘extremely important to understand the customer' and only 48 per cent said it was ‘extremely important to understand the brand'. When asked to explain why, here are some of the answers:

- ‘They are the heart of success.'

- ‘So you know you're going in the right direction.'

- ‘They are the starting point for any brand success.'

- ‘I work on the theory that the better we understand the customer, the better equipped we are to communicate with them in a way that engages them. That's the theory at least.'

- ‘They are the reason we exist.'

- ‘Because the customer pays our wages, not the brand.'

Consider these findings in a context where market research dominates conversations and briefings. When I started in this industry, marketing briefs were just that – brief. Today, they are accompanied by copious amounts of research and an inevitable warning: ‘we have loads of research but little insight'. It's worrying to me that 62 per cent of marketers want to better understand the customer rather than their brand at a time when they understand their customers better than ever, or at least have the research to prove it. Customer obsession is driving strong brand thinking backwards.

Why is customer obsession happening?

When studying psychology, I was told the ‘why' is not that useful. The issue of why I overeat doesn't stop me from overeating. What's needed is cognitive behavioural therapy, or changing thoughts and structuring my world in a way that makes it harder for me to eat. For example, I committed to following the principles of Intermittent Fasting and shared this with everyone I know, creating accountability. The question of ‘why' customer obsession is happening is complex, and I only have half an answer. (But chapters 6 to 10 cover my solution to this obsession.)

One reason for a push towards the consumer over the brand is this: it's easier. Brands are complex and challenging. There's a belief by marketers that acting on what the consumer says is a safe bet. It's the modern equivalent of the adage ‘Nobody gets fired for buying IBM'. In the 1960s and 1970s IBM was the market leader, so, when buying new software, you chose IBM over cheaper alternatives in the belief it was rock solid and would deliver. You couldn't go wrong. Today, marketers might believe they can't go wrong if consumer insights back their recommendations.

To understand why consumer obsession has taken off, I had a chat with a good friend, Mark Green, who has strong views on consumer obsession. Many years ago, Mark and I worked together at Saatchi & Saatchi. These days he heads up one of Australia's most successful agencies, Accenture Interactive The Monkeys, formerly known as ‘The Monkeys'. Here's a summary of our chat (leading questions included):

Adam: Mark, why the obsession with the consumer today?

Mark: I think for those who lack conviction, relying on what the consumer says is a great middle-management tool. Because it's an opinion that they, the marketer, don't have. They are not starting from a position of understanding, certainty or confidence in their judgement, so, therefore, they'll resort to someone else's opinion as to what to do (the consumer).

Adam: So why don't you think they have certainty?

Mark: Well, brand management is about sacrifice. You have to stand for something, and that means not standing for a whole lot of other things. And inherent in that is a decision. And if you're not prepared to decide in the first place, you're sitting on the fence, and a lot of people like to sit on the fence.

Adam: OK.

Mark: You can't build the future from what's happened in the past. That's the leap where you need skill and conviction to try things that are different or haven't been done before. You have to have vision and confidence and skill.

Adam: Where does the skill come from?

Mark: Hmmm. It's the skill in understanding brands and what a brand stands for. And once you understand that, it's the skill in understanding how a brand connects with an audience. These are the skills that are lacking today.

Adam: Thanks, Mark.

Mark: Adam, do you want to try one of the new beers we've created?

Adam: Thanks, Mark.

I agree with Mark, particularly the point around ‘skill'. It's rarer and rarer to find those who have the skills needed to define a brand.

How is customer obsession happening?

In the world of brand building, it's heresy to suggest you shouldn't listen to the consumer. I'm not saying market research is a waste of time (I'm neither brave enough nor stupid enough to suggest this). However, I think the balance between data collection and brand management is out of whack. Data is ubiquitous and omnipresent. The ability to measure everything a consumer does means knowledge about the consumer has increased, but knowledge of the brand has decreased. To complicate things, it's easiest to collect data from the most frequent users of your brand. Data is blinding marketers to strategic thinking and making them only look at the here and now. We're drowning in what many businesses are now building: a ‘data lake'. (The name ‘data lake' is probably a nerd joke about organisations striving to construct a data lake and then drowning in data.)

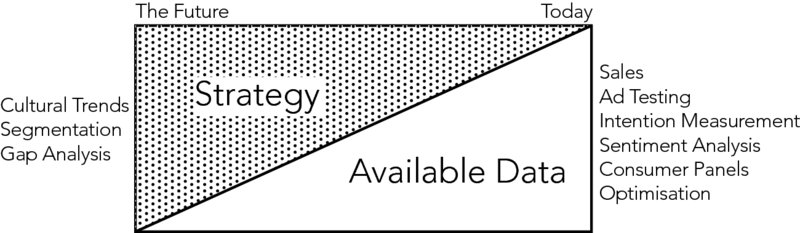

Figure 1.2 roughly shows the flow of marketing activity from strategy (thinking about tomorrow and how to get there) to execution and the things we need to measure and respond to today.

Figure 1.2: flow of marketing activity and available data

At all stages, it's possible to collect data and insights to inform decisions. However, transactional data (at the far right of the diagram) appears to be driving business decisions and helping us to live in a today-focused, short-term-thinking style of brand management. The ‘Data' on the right-hand side refers to:

- Sales data, which can be broken into weekly, daily or hourly segments. It is this type of data that many in business are poring over. You might have been part of a Monday morning meeting eagerly assessing sales results from the previous week before optimising and tacking week to week.

- Ad testing, which is not reliable. Ad testing puts unfinished ads in front of consumers and asks them if the ad will make them buy. The ads are often presented in cartoon form and can get a little annoying. More on this later.

- Intention data, which is about whether the customer wants to buy your brand or product. Are they looking for it online? Have they visited the website or downloaded the app? Are they in the purchase funnel?

- Sentiment analysis, which is about how customers express their thoughts and feelings about your brand. But it's likely to be your customers saying these things, and therefore a very (in most cases) small percentage of your entire market.

- Consumer panels, which are online panels or Facebook groups companies consult with and ask questions. The customers are like pigeons in a Skinner Box, pecking at a response panel for their next gift card.

- Optimisation, which appears to make sense — but messaging (ads or communications) is often optimised for someone who has no intention of purchasing. Or, worse, has already purchased. How many times has an ad popped up on the internet after you've bought something?

Companies obsess about each of these insights. They attempt to work out how to turn an accidental click on a banner ad into an algorithm hell-bent on following you around the internet until you buy the product (or install an ad blocker). They obsess about short-term sales data rather than rallying the organisation around a brand idea. They get stuck in a weekly cycle of Monday morning numbers.

The data featured on the right-hand side of the figure doesn't help in understanding brands or in building long-term business strategies. This type of data can, however, determine the rhythm of business. It can suck time from what ultimately drives real value for the business, such as segmentation, gap analysis and brand positioning. These can be forgotten when marketers obsess about existing buyers or those about to buy their product. It is for these reasons that we are becoming even more customer-obsessed, as there is so much data available out there to collect.

It's tough to define what a brand stands for, and then to communicate the brand consistently in everything an organisation does. But this needs to be the priority of marketing. Examining the metrics of consumer data and sentiment risks creating generic and homogenised content. It is the enemy of distinctiveness.

Customer Obsession is Over

Customer insights, and understanding the customer wants and needs, are always going to be a part of what marketing is about. However, the abundance of consumer driven data, coupled with the increasing need to cover one's own ass, has made many a brand builder ‘customer obsessed'. The next few chapters delve a little further into why that is such an issue.

Notes

- 1 Baxter, M. (2018). ‘Think Different. Yeah, not so much'. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-you-should-sell-your-apple-shares-mat-baxter/

- 2 Zealley, J. (2019). ‘Meet the new brand of CMO'. Accenture Interactive. https://www.accenture.com/ca-en/insights/consulting/cmo

- 3 ibid.