chapter 3

listening to the consumer eliminates value

‘I love brands. I love it when they advertise to me and encourage me to visit their website. In fact, the more I see of their advertising and the more time I spend on their website, the better!'

Who has ever said this? I believe the answer is, ‘No-one, ever.' Unless your brand caters to fanatics, such as sports enthusiasts or fashionistas, most people don't want to be bothered by most brands, most of the time. I estimate that consumers think about your particular brand somewhere between 0.00 per cent and 0.01 per cent of the time. People don't care about brands, especially your brand.

Think about what ‘consumer-centric' means. If you put what the consumer wants and needs at the heart of your business, would your brand even exist? If it existed, would it advertise? If it advertised, would it advertise often? Understanding what the consumer wants and needs and genuinely delivering on it might mean your brand doesn't exist at all. Sorry, but someone has to say it.

Dinner with Gladwell

Malcolm Gladwell is a best-selling author and way ahead of his time in describing today's holy grail: going viral. His first book, The Tipping Point, argues that trends operate in the same way as an epidemic. The book starts with the fascinating story of old-fashioned shoe brand Hush Puppies unexpectedly becoming the shoe of choice for downtown Manhattan hipsters. This trend was picked up by key fashion designers and eventually led to the shoes being available in every shopping mall in America. As Gladwell writes,

Ideas, products, messages and behaviours spread just like viruses do. Their chief characteristics — one, contagiousness; two, the fact that little causes can have big effects; and three, that change happens not gradually but at one dramatic moment — are the same three principles that define how measles moves through a school or flu attacks every winter.

When I discovered he was coming to Australia for a speaking event, I emailed his assistant with an invitation for dinner at Tetsuya's, a top-end Japanese restaurant in Sydney. To my shock, he accepted. Around the table, among others, were Dennis Paphitis, founder of Aesop; Paul Bassat, CEO of Seek; Charmaine England, the then marketing director of Unilever; and Karen Wong, marketing director of Coca-Cola. This interesting bunch of people are keenly interested in understanding the consumer.

After some small talk, the table asked Gladwell questions ranging from ‘Should brands have a purpose?' to ‘How should brands spend their advertising dollar?' He answered the questions with humility and insight in a slightly tired, jaded and flat voice. Finally, someone asked this question: ‘What do you think people want from brands?' The simple question elicited an even more straightforward answer. After a quiet pause Gladwell said: ‘People want to be left alone.' According to Gladwell, people don't want brands to entertain them, to have a higher purpose, to create content or to advertise. Brands, he argued, should be available when the consumer wants or needs them.

It was a refreshingly honest perspective. People in business like to think their product or service is held dear in the consumer's heart. There are exceptions, but for most consumers, this isn't the case. Most go about their day, not caring about your brand or the category that your brand operates in. They want to be left alone. Makes sense, right? I call this the ‘Consumer in Control' model, which is detrimental to business. Here's why.

Consumer in Control

In this model, we are only in consumers' lives on their terms. When the consumer is in control, both 1) advertising and communications, and 2) developing the actual product or service are under threat, a situation that ultimately removes value from your brand. Let me explain.

Advertising with the Consumer in Control

Imagine if we could advertise to a consumer when they wanted us to. In this scenario, they can view a hyper-targeted, hyper-personalised ad in the moments before purchase. Once viewed, the ad disappears, never to be seen again by them or anyone else. Does this sound like personalised advertising nirvana and a much cleaner communications landscape? To me, it seems like some kind of hell. Further, a hell that will destroy brands and businesses.

There's a glimpse of this horror in the wild film Minority Report released in 2002. Tom Cruise's character walks into a Gap store, and a virtual digital assistant asks if he likes the ‘assorted tank tops' he bought last week. Personalised digital ads also bombard Cruise as he walks through a screen-lined lobby. This imaginary world was seen as scary and dystopian when the film was released. Today, it doesn't seem so far-fetched. My friend Faris Yakob also happens to be a futurist. He wonders why, if most people see Minority Report as a dystopian view of the future where free will evaporates, our advertising friends think it's nirvana?

The broader business and marketing community is becoming very excited about the idea of ‘personalisation' of messaging, and messaging only where and when the consumer wants it. However, I'm not aware of any research that says people want to be advertised to in this way, or that hyper-personalised advertising is a good way to build a brand or business. Just because we have the ability to do more personalised and targeted communications doesn't mean we have to use it.

In 2005, The Journal of Advertising Research published an interesting article by Tim Ambler titled, ‘The Waste in Advertising Is the Part that Works'.1 Ambler argues that consumers believe a brand is of a higher quality if they think a lot of money was spent on it. The waste in advertising — from expensive production costs to extravagant media spends blasting the same message to everyone — works in the same way as the handicap principle in nature.

The handicap principle is a beautiful concept best described using peacocks as an example. When a male peacock displays its luxurious plumage, he signals that he has plenty of resources at his disposal and therefore he is fitter, sexier and better than his competition. The same principle is at work when a person spends a large amount of money on a sports car. It signals that because they can afford an expensive, silly car, they must have an abundance of resources — money — at their disposal.

Ambler argues this principle operates in advertising. Big productions and high media spend signal to the consumer that the brand is serious and confident of future success. This can't be achieved in hyper-targeted advertisements. In a world of the Consumer in Control, we don't know how the consumer hears about our brand. No consumer in control will choose to be consistently advertised to, and yet, as I'll get into, this is the premise for how brands grow.

Byron Sharp wouldn't be happy

Listening to the consumer, only appearing when they want you to and making things as easy as possible is not only wrong, it's the opposite of how marketing works. As the modern master of marketing, Professor Byron Sharp, puts it, ‘No marketing activity, including innovation, should be seen as a goal in itself, its goal is to hold on to or improve mental and physical availability.'2 According to Sharp, mental and physical availability is the key to brand growth.

Following this thinking, a marketer's job is twofold. Firstly, to ensure a brand becomes stuck in consumers' minds and is easy to recall when they need the category that the brand falls within (e.g. when someone thinks, ‘Gosh I'm thirsty', a marketer's job is to ensure that the person thinks of their brand before any other). This is called ‘mental availability'. Secondly, if the brand is easy to remember (that is, there's mental availability), then they must ensure that there is physical availability too: the brand must be easily bought or consumed. So if we build on the previous example, the person thinks, ‘Gosh I'm thirsty', then the marketer ensures there's mental availability (that is, their brand is thought of first) and that there is physical availability (that is, it's easy for the consumer to get that particular brand). All of this can be summed up in Coca-Cola's global strategy from some years ago, which they described as being ‘within arms-reach of desire'. The ‘arms reach' speaks to physical availability; the ‘desire' speaks to mental availability.

With regards to mental availability, Sharp told me over dinner,

Adam, there are two fundamental rules about how to spend your advertising budget. Rule number one is spend as much as you can. And rule number two is to divide your total spend and spend around a twelfth of it every month.

Here Byron is making the point that in order to stay ‘top of mind' you need to constantly remind consumers of your presence, and you never quite know when the need will ignite. If you ask the consumer what they want, they won't say ‘constantly advertise to me'. We all know they say something closer to the opposite.

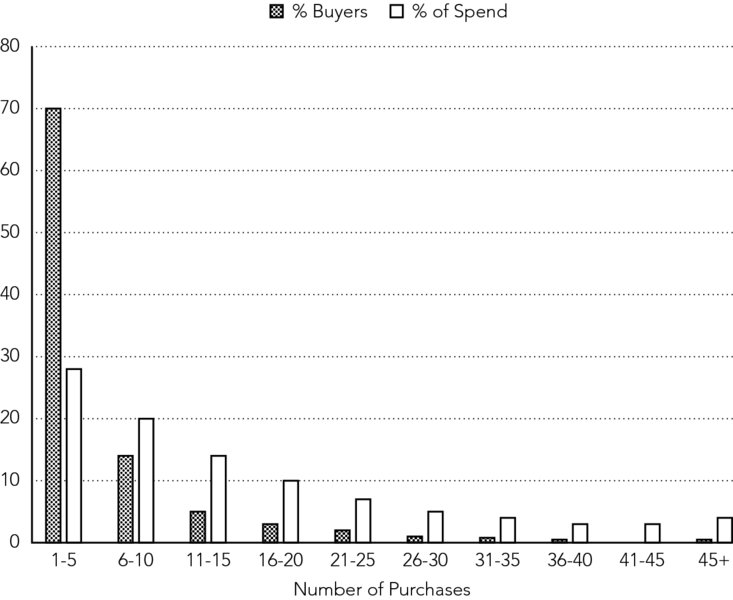

There is another issue with the hyper-targeted Consumer in Control approach to advertising: your brand will not grow. You see, you'll only reach your existing customers because potential customers don't know you exist, so they'll never want you to advertise. In most consumer product categories, the user spread follows a negative binomial distribution (NBD). This is a statistically predictable distribution curve first discovered by Professor Andrew Ehrenberg. This model suggests that across all categories, a few people buy a significant portion of your brand, but most buy the brand infrequently. The figure 3.1 (overleaf) was created by my friend Wiemer Snijders, whom I introduced in chapter 2. It's from the non-alcoholic beverages category, indicating the typical customer base for a popular brand. The graph shows the number of people that buy a particular brand within the category throughout the year.

Figure 3.1: a lot buy a little, a little buy a lot

Source: The Commercial Works client data, beverages, 2016, 52 weeks' buying

As Snijders tells us,

The brand is well known, yet almost three-quarters of its buyers bought it five times or less, together realising nearly 30% of annual sales. This seems surprising, yet marketing science says that it is quite normal. The pattern is closely predicted by a statistical curve, the negative binomial distribution or NBD. Every brand's customer base is like this … This pattern in buying behaviour is so regular that it can be successfully modelled, and the predicted values used to understand and benchmark actual or future brand performance measures.3

Snijders argues the negative binomial distribution is the statistical pattern that underpins much of the evidence presented in Byron Sharp's game-changing 2010 book How Brands Grow. I recommend the book highly.

It's likely your brand acts in this way as well. Wiemer points out, ‘In 60 years of research, no brands — from global market leaders to startup challengers —have been found with anything other than NBD loyalty.'

Without the knowledge that most people buy a brand infrequently, businesses run the risk of listening to the wrong consumer. In fact, they often only listen to those with the loudest voices who are invariably the biggest users in the category. These are the ones who are vocal on social media channels. Many businesses put together their own consumer panels featuring medium to heavy users of the brand. However, it's likely the business already meets the needs of these consumers. Instead, the brand should focus on appealing to light users and those who have never bought the good or service. This is also where their advertising budget should go — to keep on penetrating into new and emerging buyers of the category. Getting data on these people before they've entered the category is really hard — hence again there is a need for broadcast communication that's always on and appears to have lots of ‘wastage'.

GME is an Australian company that designs and manufactures emergency beacons and radio communication devices, such as CB radios, with a reputation for being rugged and tough. Their core customers are off-road 4WD enthusiasts. If the company creates a product that's considered ‘soft' or contrary to the needs of hard-core adventurers, their loyal but small customer base complains. As a consequence, GME's customer base has remained very niche because it resisted innovating or targeting new consumers. Unfortunately for them, other companies have entered the CB radio market with a more contemporary offering and have won significant market share. For example, CB radio manufacturer Uniden has cute two-way radios for adults and kids to play with together. They are just a bit of fun and more like a toy than a serious CB radio. However, when these kids grow up, they'll be more likely to think of Uniden rather than GME if they're in the market for a CB radio. GME is still a strong brand with a very loyal following in part because of the superior quality of its products. However, it will be interesting to see how they evolve and chase a new group of consumers. In many cases, companies should pay less attention to their core consumer because it prevents them from focusing on new customers.

Personal communication isn't all it's cracked up to be

In our quest to personalise brands and give consumers attention, marketers spend time, effort and money building a ‘personalised relationship' with the people they ‘meet'. By ‘meeting', I mean have you ever clicked on a pop-up ad or visited a website only to be stalked on the internet by annoying ads? Those ads are delivered programmatically. The advertising algorithm knows a bit about you and why you visited, and the creative messaging is tailored to you and will continue to pop up wherever you are on the internet. You might go online looking for shoes. Days, weeks and months later, you are bombarded with ads for shoes. The impact of personalised communications is still pretty ropey. I doubt many consumers would request personalised ads. In fact, most people think they are kind of creepy.

Personalising consumer messaging has several issues:

- The consumer doesn't care about your brand, and advertising is a poor tool to convince people of anything. Advertising is a long-term game. It works by creating little impressions of the brand, and those impressions come along with associations. We are not as susceptible to advertising as some snake oil salesmen would like us to think. The last thing most people want to deal with is a targeted ad or conversation.

- Advertising is most effective when it ‘seeps' into the minds of consumers. It's the reason why occasionally it makes you laugh. When we make people laugh and feel good, their defences come down and we can create a positive impression. The personalised information is more aggressive. Robert Heath examines how successful advertising drips into the consumer's mind and doesn't become caught in an argument.4

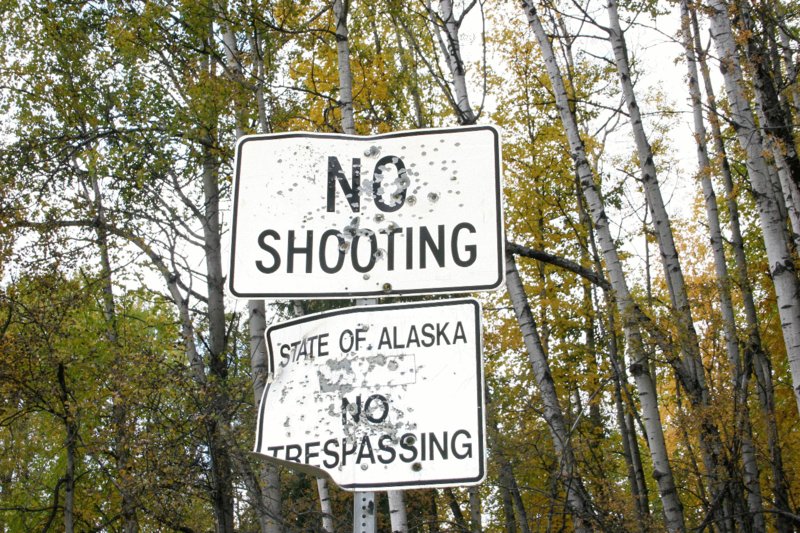

- Aggressive selling causes ‘reactance'. How do you react when someone strongly argues a point with you? You probably respond defensively and mount a counter-argument, even if it's just in your head. You are building what psychologists call ‘reactance to messaging'. Reactance happens when someone feels they have limited choices or alternatives. Look at figure 3.2. This is what happens when advertising tries too hard.

Figure 3.2: when advertising tries too hard

Source: Photo by Katherine Hood on Unsplash

Monkey see, monkey do: advertising also works by creating a social norm and showing consumers what's trending in popular culture. This creates an ‘assumptive social norm'. People believe something is popular because it's widely advertised, which suggests everyone else must be buying it. This informed the messaging for Foxtel with its tagline, ‘We're a Foxsporting Nation': it gave the impression that everyone was subscribing to Foxtel. Social norming is impossible to achieve through personalisation because of its application — changes in societal attitudes can't happen through messaging crafted to the individual.

Personalisation focuses on the wrong people. Personalisation only occurs within an audience that is already purchasing (or thinking about purchasing) that brand, which leaves the rest of the market untouched. It's the opportunity cost of personalising your brand with people who have a relationship with you anyway, versus the mass market, which is where the opportunity lies for most businesses. This was the case with GME.

Product and service design with the Consumer in Control

Imagine a scenario in which you listen to the consumer and create a website, app or digital experience that's intuitive and easy to use; they can enter, exit and find what they need in one click or swipe or voice-activated control. If you work in web design, I'm sure you've come across Steve Krug's book Don't Make Me Think. Web designers aim to make navigating a website as easy as possible by considering where people look on the screen for information, how many clicks it takes to make a purchase and how to create clear ‘calls to action'. This logic is now being applied to brands. The belief is, the easier it is to enter and exit your brand experience, the more consumers will like you and reward you with continued patronage.

Daniel Kahneman is a psychologist and Nobel Prize winner. His 2011 best-selling book Thinking, Fast and Slow outlines the two systems that drive the way we think. Kahneman describes these as System 1 and System 2. System 1 is fast, intuitive and emotional. It's like a super computer operating on intuition, experience and gut feel, processing 11 billion bits of information a second and instantly jumping to a solution. System 2 is slow, lazy and sequential. It's super smart but requires significant effort to work through problems. It only processes about 40 billion bits of information per second and is exhausting to run.

The book is a brutal, slow read because it's very dense and filled with information better suited to System 2 thinking. I reviewed the book for The International Journal of Advertising, but in truth I didn't finish reading it because it was too long and a little too boring for me. I wish Kahneman had written the book for System 1 thinkers, with more stories, more emotion and more repetition of key information.

Even though the brain makes up about 2 per cent of total body weight, it accounts for around 20 per cent of energy usage. Humans are built to conserve energy and not to burn energy unnecessarily. When it comes to thinking, we take the path of least resistance. This is System 1 in action: fast, intuitive and going with the flow. If we are presented with two chocolate bars and one is easier to reach, we'll choose the one that's easier to reach. If one of the chocolate bars is perceived to be more popular, we'll select that one in the belief that it's better. If we've eaten one of the chocolate bars before, we're more likely to choose it again. If we've seen an advertisement for a chocolate bar, we're more likely to choose it because it's familiar. The brain is continually searching for shortcuts to conserve energy, and these shortcuts can lead to what's known as cognitive biases. This leads marketers to embrace content that has a high degree of cognitive fluency.

Cognitive fluency is the ease with which we process information and determine what that information means. It refers not only to the experience of a task or processing information, but the feeling people associate with that task. We are more likely to remember and believe information if it's easy to process.

However, there's an equal and opposite concept known as cognitive disfluency, which is the enemy of human-centred designers and Steve Krug devotees. It says we process information depending on the required effort and if it's easy (fluent), we find it much more pleasant than if it's difficult (disfluent).

Why human-centred design is killing brands

It's not only advertising and web design that's putting the consumer at the centre. Human-centred design (HCD) is a design and management framework that considers the human perspective during the problem-solving process. The brand, product or service is designed from the user's perspective. It observes the problem within the user's context then brainstorms, conceptualises, develops and implements a solution. HCD emerged from Design Science and Ergonomics.

As an aside, I studied Ergonomics at Murdoch University, for which I received my only undergraduate A grade. I observed that when you turn the tap on in the shower, you need to reach under the showerhead and as a consequence, you get blasted with cold water. Despite my undergraduate breakthrough, the shower at my house still has the tap located behind the showerhead. Every morning, I think of ergonomics, my A grade and the fact that because it's cheaper and easier to run the tap from the same water pipe as the showerhead, we are destined to have poorly designed showers. I'm pleased to hear many showers built today have mixer taps to the side. One day I hope to enjoy this design at my home.

If you want to read more about HCD, head to ideo.com. IDEO is a global design company that wants to answer some of the world's big questions (such as how to navigate disruption and thrive in changing times) using design.

Watching IDEO's Paul Bennett in a TED talk informed my understanding of HCD. Bennett talks about being asked by a healthcare system in Minnesota to describe what the patient experiences. He said the healthcare team had expected to be shown a series of graphs and Powerpoint presentations, but instead, IDEO showed them a video of a hospital ceiling. This, the team said, is the patient experience at most hospitals — staring at a grey polystyrene ceiling with yellow lights. Following this insight, the healthcare team made several small but significant changes, including decorating the ceiling. Watching the video reminded me of hospital visits during my childhood because of bad asthma. The ceiling consisted of fitted ceiling squares with loads of little holes in them. I spent many days counting the number of holes in the ceiling with the aim of not losing count. Because there were thousands of holes, I invariably lost count, but it kept me entertained as I lay there, short of breath, for hours on end. I empathised strongly with the IDEO case study.

Because HCD has many interesting applications, it might be challenging to recognise how HCD is killing brands and businesses. Let me explain.

This is a typical process using Human-centred design (HCD).

- Empathise. Understand the consumer and the context within which they use the product or service.

- Define. Articulate a problem to be solved. Theme insights from stage 1, cluster the findings, weigh up which areas of use or interaction between product and consumer you want to address.

- Ideate. This is about developing ideas that overcome the barrier or harness the opportunity identified in stage 2. A long list of ideas is generated and refined through a grading and prioritisation exercise.

- Prototype. Develop an MVP (minimal viable product) from the one or two ideas that float to the top.

- Test. These prototypes are tested and evaluated.

This process puts the consumer at the centre and takes an empathic approach to design. But there's a significant flaw. Where does a ‘brand' fit in this process? I'm sure if you work in the industry you'll be able to define where brand thinking comes in, but it's rarely if ever documented. Of all the HCD processes on the market, I couldn't find one that had the brand as its core or North Star. That's not to say it can't be added. I'm sure it can. However, brand thinking, both philosophically and practically, is not part of HCD and, on the rare occasions it is, it's certainly not the core of it. I think that many in the HCD community still shudder at the thought of the brand like it's a dirty word. It's not ‘cool'.

To be blunt, HCD is not about building brands or businesses. It's about creating a more efficient and seamless world for the consumer. You could argue it's about eliminating friction and creating a more streamlined and efficient user experience. There's that word again, ‘efficiency'. Consumers don't really need flourishes like wide fins on their cars, they don't need moments of play on a website that stop them from entering certain areas until they complete a fun task, and people certainly didn't need the myriad fonts that were available on Apple computers when they launched.

The whole premise of having to find a problem to fix before applying creativity worries me too. It leads to efficiency, but not breakthrough thinking. HCD is like a truck slowly moving along a pot-holled street fixing the holes as they see them one by one — it's a terribly inefficient way to rebuild a road, let alone a business.

Let's imagine a future in which all brands, products and services have HCD principles applied to them. Brands are as ‘efficient' as possible, as they understand the consumer more and build a product or service around what they want — not what's best for the brand. Here's what could happen — I call it creating a Teflon brand.

How to create a Teflon brand

Imagine you're the CEO of Twitter and it's 2017. You're worried about the drop-off rates of tweets and you want to make the experience a little easier for consumers. You want less friction and you want to not make people think too hard. You conduct a HCD study to inform the product development of your platform. Here's my fly-on-the-wall imagining of this process:

- Empathise. Twitter's data indicates usage drops off when people find they can't express themselves in 140 characters. It happens when people are in a time-pressured situation — such as using Twitter while watching TV. Twitter decides the pain point is the restriction to 140 characters.

- Define. Allow Twitter users to use more than 140 characters.

- Ideate. Suggestions include removing the word limit entirely or slightly increasing the character limit.

- Prototype. Options are prototyped and tested with consumers.

- Test. A decision is made to double the number of Twitter characters to 280.

And that's exactly what Twitter did in a bid to stop people getting annoyed because they couldn't say everything they wanted to in a short tweet. Before they made the change, research companies measured the proposed impact and found most people felt positive about the increase.5

Now, imagine that during these discussions someone said, ‘Oh you can't do that. Twitter's brand is tightly aligned to 140 characters', with another person chiming in with, ‘The 140-character limit comes from the days of SMS limits of 160 characters. People don't remember this, but the logic is pretty cool.' Reflections such as these don't come up in a usability lab or a focus group.

Twitter research showed that increasing the character count from 140 to 280 didn't change the length of most Twitter posts. For those who like stats: ‘Only 5% of Tweets sent were longer than 140 characters and only 2% were over 190 characters.'6 But one thing certainly changed. Twitter compromised its unique selling proposition (USP), or central organising thought. A platform celebrating brevity suddenly doubled the length of tweets. Author JK Rowling wrote of the decision: ‘Twitter's destroyed its USP. The whole point for me was how inventive people could be within that concise framework.' It was a view supported by many, including horror author Stephen King who added: ‘What she said.'

Twitter's brand was modified because of consumer insight. But user behaviour didn't change that much, and the brand's proposition has been permanently compromised because it used to stand for ‘really short messages' and now it stands for ‘quite short messages'.

One year after the change, Slate published an article by Will Oremus titled ‘Remember when longer tweets were the thing that was going to ruin Twitter?' He wrote,

At a time when Twitter is under scrutiny for its role in radicalizing right-wingers and fomenting anti-Semitism . . . and when CEO Jack Dorsey says he's rethinking everything: The anniversary of its character-limit change doubles as a reminder of a time when people didn't want Twitter to radically rearrange its core features.7

I'll tread carefully. Those working in HCD are close-knit and very vocal. Criticising the industry isn't done lightly, so here's some supporting evidence. Brent Smart is one of Australia's top marketers and former CEO of creative agency Saatchi & Saatchi. His marketing team won the annual Mumbrella Marketing Team of the Year award. Since becoming Chief Marketing Officer at insurance company IAG, he's been part of some incredible and highly effective brand-building work. In 2013, Smart said of customer journey mapping, a central tenet of HDC,

I don't think it delivers competitive advantage. It's hygiene . . . When you focus on efficiency, you're able to show a commercial impact from marketing pretty quickly, but you're missing the bigger aspect of this conversation. Too many marketers focus on the efficiency side as opposed to the effectiveness side of things.8

Brands that apply HCD or customer journeys to increase efficiency and help consumers glide through their customer experience are building Teflon brands. They are not sticky, they are less memorable and they, therefore, reduce mental availability. This strips the value from the business.

A Teflon world

In 2018 The New York Times published a revealing article headlined ‘How Amazon steers shoppers to its own products'.9 It's worth a read if only to learn the difference between a monopoly and monopsony. In 2009 Amazon embraced the private label business and began offering unglamorous products such as batteries in its Home Basics category. Amazon's brand was available along with well-known battery brands Duracell and Energiser. When consumers run out of batteries, they don't ask Amazon's virtual assistant, Alexa, for more ‘Duracells' or more ‘Energisers'. They ask for more batteries. They care less about the brand and more about getting new batteries. The private-label batteries also happen to be 30 per cent cheaper.

Amazon told The New York Times, ‘We take the same approach to private label as we do with anything here at Amazon: We start with the customer and work backwards.' Starting with the customer or customer experience is killing brands, because people don't need brands. They need the product. A company that puts the customer at the heart of its business can make brands redundant and, if not redundant, then generic.

Now bear with me as I become somewhat hyperbolic to make a point. When you watch a movie set in the future, the themes are similar. Everyone wears silver or red spandex, they have similar haircuts and they walk in unison. The lives of these futuristic people are depicted as seamless, frictionless (bloody HCD) and somewhat detached. There's often one mega-brand or company that controls everything. In The Terminator, it's Skynet. In Pixar's WALL-E (one of my top 100 movies of all time), mega-company Buy n Large controls everything from government to space travel to yoghurt. Science fiction takes an element of truth from today and imagines ‘what if' in the future. In this world, brands disappear because the consumer doesn't need them. They need a product or service.

Following the imagination of science fiction writers, corporations are heading towards two outcomes. They will either be swept up to become a Buy n Large of their time — that is, fall into line with the business that controls everything. Or they will create something that's both different and distinctive — a brand with an idea. For the latter scenario to become a reality, a brand has to know what it stands for.

If you're in the whacky creative fringe, you might be nodding along saying, ‘Darn right, the answers to life's questions are always in the movies'. But maybe you want to know what the science says.

We're already partly in a Teflon world

Consider the design of London's double-decker buses or Melbourne's trams. Both used to be ornate, with flourishes. Now both are streamlined and aerodynamically efficient human transport capsules lacking personality. Look at modern buildings: efficiency rules. We are already on the way to creating a WALL-E-like world: a super comfortable Teflon experience. Some of us want to challenge this and add some grit, cognitive disfluency and effort into the world we are designing.

Verda Alexander is responsible for designing many cool and fun workspaces. After designing many typical ‘startup'-style workspaces with skateboard ramps, music rooms and in-house beer taps and baristas, she has since changed her focus and wants to design a workspace that is

. . . a little less comfortable and a little more challenging . . . Life is enriched by challenges. To face adversity, to labor is to be human . . . Friction gives us the ability to slow down, to focus, and to steer our attention where we want it to go..10

I love this approach. It reminds me of Building 20, which I read about in Steven Johnson's book Where Good Ideas Come From. Building 20 was a makeshift wooden structure built during World War II on the central campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The building was always considered temporary. When someone moved in, things were reconfigured, walls were bashed down or altered to fit their needs. The building was somewhat dilapidated and never ‘perfectly' designed. It wasn't given a formal name or a dedicated purpose. But many unlikely meetings and unexpected conversations happened in Building 20 that led to the development of many new ideas. Several Nobel Prize winners worked there — especially in radar and nuclear physics. I discuss the importance of effort in chapter 5 when outlining the hope for stronger brands and businesses.

![]()

Many marketers are inadvertently creating Teflon brands. By listening to the consumer and giving them what they think they want, brands can slip in and out of consciousness. Being consumer-centric leads to brands and businesses that are only relevant when the consumer wants them to be. This isn't ideal. If you make things easier for them, be aware you may strip value from your business. The less they need to think about you, the worse it is.

Don't let this thought slide by

I hope I've convinced you that a consumer-centric approach will eradicate value from your brand and business. It leads to a lack of mental availability for your brand, meaning that when consumers have a need for you, you won't be there. This is a significant issue. It also devalues your brand because it doesn't reach people who rarely use the category. The bulk of sales are from people who rarely buy your brand. So unless you have non-stop advertising to the unengaged masses, there's little chance you'll pick them up. Further, if your product experience is seamless, it leaves a minimal impression in the mind for next time.

Notes

- 1 Ambler, T. (2005). ‘The waste in advertising is the part that works'. Journal of Advertising Research, vol. 44, iss. 4.

- 2 Sharp, B. (2012). How Brands Grow: What marketers don't know. Oxford University Press.

- 3 Snijders, W. (2018). ‘The unbearable lightness of buying, as told by an old jar of pesto'. Mumbrella. https://mumbrella.com.au/the-unbearable-lightness-of-buying-as-told-by-an-old-jar-of-pesto-550525

- 4 Heath, R. (2012). Seducing the subconscious. Wiley.

- 5 Piacenza, J. (2017). ‘U.S. adults warming to Twitter's 280-character expansion'. Morning Consult. https://morningconsult.com/2017/10/13/u-s-adults-likely-favor-twitters-280-character-expansion/

- 6 Rosen, A. (2017). ‘Tweeting made easier'. Twitter blog. https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/product/2017/tweetingmadeeasier.html

- 7 Oremus, W. (2018). ‘Remember when longer tweets were the thing that was going to kill Twitter?'. Slate. https://slate.com/technology/2018/10/twitter-tweet-character-limits-280-140-effect.html

- 8 McIntyre, P. (2019). ‘IAG CMO Brent Smart: martech is “hygiene”, everyone's doing it, no competitive advantage'. Mi3. https://www.mi-3.com.au/15-07-2019/iag-cmo-brent-smart-martech-hygiene-everyones-doing-it-and-theres-no-competitive

- 9 Creswell, J. (2018). ‘How Amazon steers shoppers to its own products'. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/23/business/amazon-the-brand-buster.html

- 10 Alexander, V. (2019). ‘I've been designing offices for decades. Here's what I got wrong'. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/90373440/ive-been-designing-offices-for-decades-heres-what-i-got-wrong