KEY IV

REFLECTIONS

After we figure out where the light is coming from, what it is hitting, and where the shadows are, we have to look at how it bounces off the surfaces it hits. These are “reflections.” They can happen on even a mildly shiny surface. We may find them on the glass of a window, ever moving waves of the sea, a bronze statue in a park, or the side of a car. Rendering reflections can give the audience information on the surface of an object and add pizazz to a sketch.

An object’s reflections depend on the quality of its surface. How shiny is it? Something like a mirror—as shiny as can be—will give you nice, sharp, clear reflections. Transparent glass can give you similarly sharp reflections, but they’re often interspersed with anything you’re seeing through the glass itself. This can soften the reflections and means you often don’t get a perfect, unbroken reflection. Matte surfaces don’t have any reflections, although sometimes you can still get reflected light bouncing off the object and filling the shadow. This happens most often with lighter objects, or ones that are a really bright color.

By thinking about how light hits an object while sketching, we’re better able to replicate it and give the viewer more tactile information.

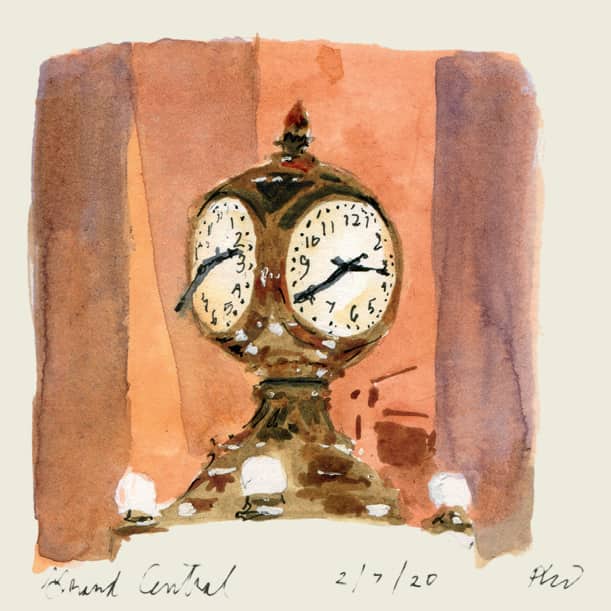

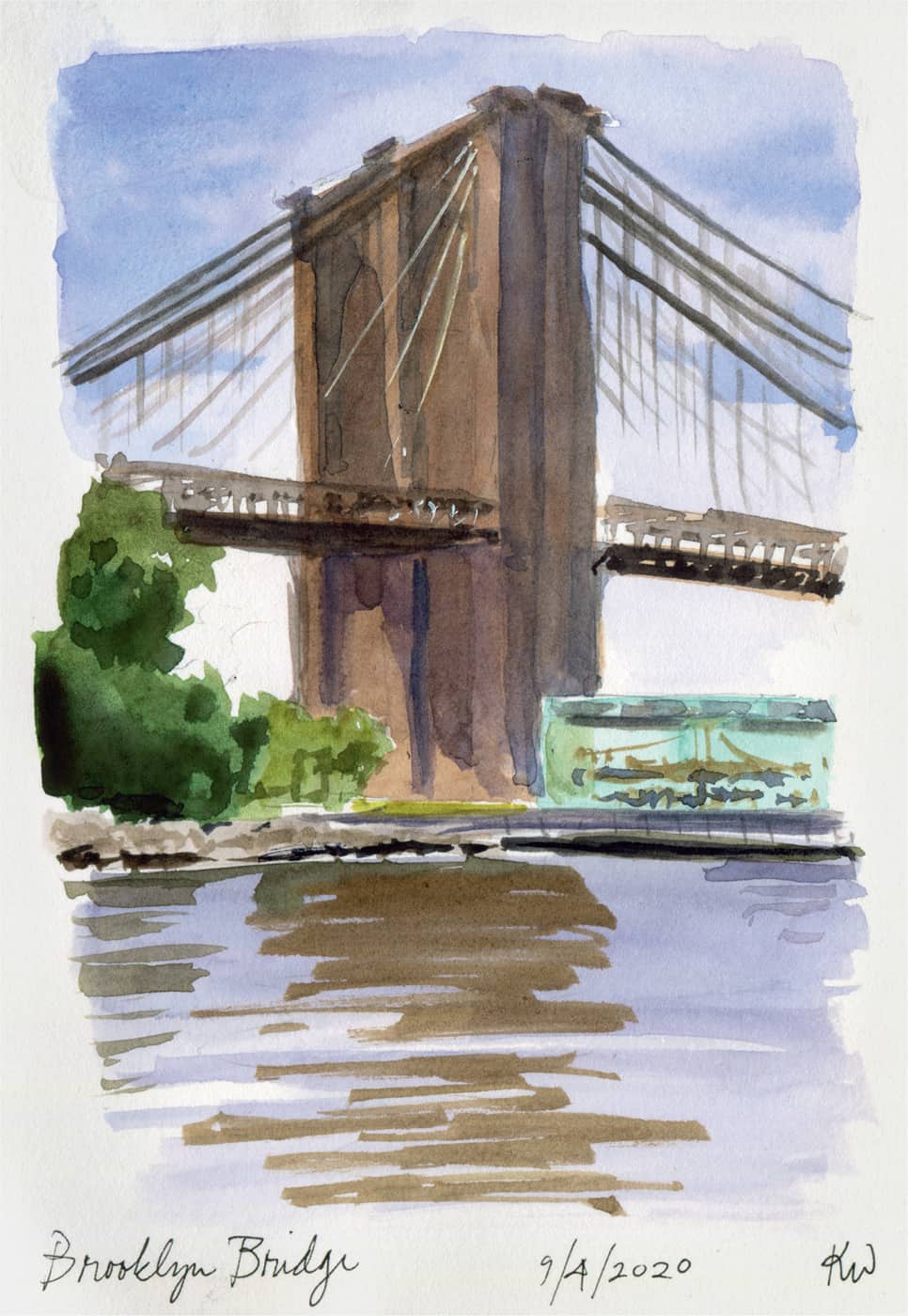

KATIE WOODWARD

Brooklyn Bridge, New York City

5" x 7" | 12.7 x 17.8 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, white Uni-ball Signo gel pen; 35 minutes

REFLECTIONS IN WATER

Some light breaks the surface of the water, and some is scattered off the surface. How much of that reflected light comes to us can depend on a number of things, especially how much the water is moving. Take a minute to examine the surface, using the provided checklist as a guide. Frequently, water is in motion and we don’t get a clear reflection, but we can see bits and pieces through the ripples. A few quick strokes can give the illusion of a reflection with very little effort!

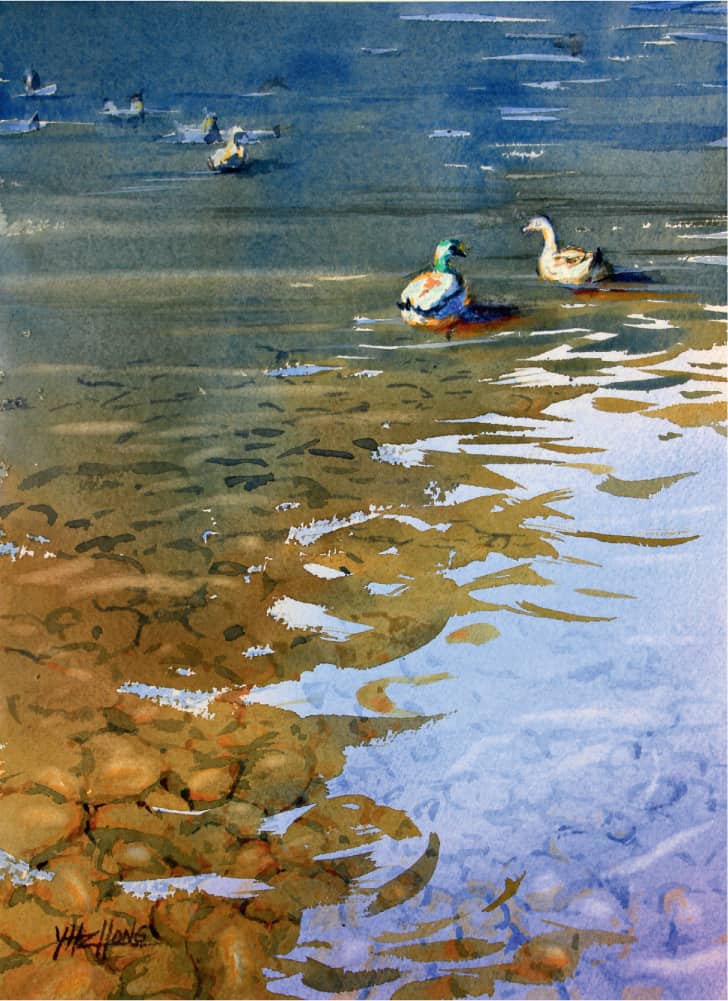

YONG HONG ZHONG

Pond Reflection, Lake Oswego, Oregon

9" x 12" | 22.9 x 30.5 cm; watercolor; 1½ hours

Look at how light the water is where it is reflecting the sky. This is juxtaposed with a darker reflection, perhaps of nearby trees? Note how the dark section is warmer and darker closer to the artist, and cooler and lighter farther away. That change gives a wonderful sense of depth. This is also a great example of being able to see something under the water, while still seeing reflections above. Note how we can only see the stones underneath the water when they are closer, and how we can see through the water better where it is in shadow rather than where we see the reflection of the sky.

Observation Checklist

How clear is the water?

How clear is the water?

Am I seeing anything under the surface?

Am I seeing anything under the surface?

Is the top still, or is it moving?

Is the top still, or is it moving?

If there are ripples or waves, how big are they?

If there are ripples or waves, how big are they?

What direction is the water moving? If there are ripples, what pattern are they making?

What direction is the water moving? If there are ripples, what pattern are they making?

Are there shadows cast on the water’s surface?

Are there shadows cast on the water’s surface?

Do you see anything reflected in the surface?

Do you see anything reflected in the surface?

Is that reflection broken up, or more like a mirror reflection?

Is that reflection broken up, or more like a mirror reflection?

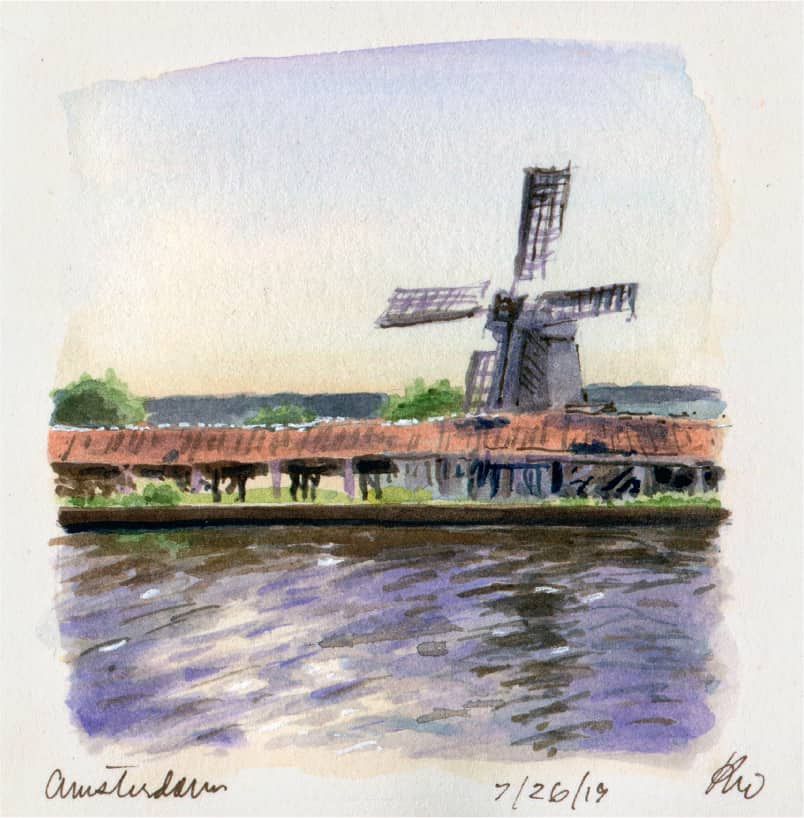

KATIE WOODWARD

Amsterdam Windmill, Amsterdam, Netherlands

4" x 4" | 10.2 x 10.2 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, white gel pen

If bright sunlight is reflecting off the tops of the ripples in the water, adding in short dashes of white can help add a little sparkle! The brightest sunlight bouncing off the water here was done with white gel pen. The lightest area is the reflection of the sun itself since it was positioned in front of me as I sketched. Some darker brushstrokes show where the windmill is reflected. Because there were so many ripples on the surface of the water, you don’t get a perfect mirror reflection of the windmill, only a suggestion of size and shape.

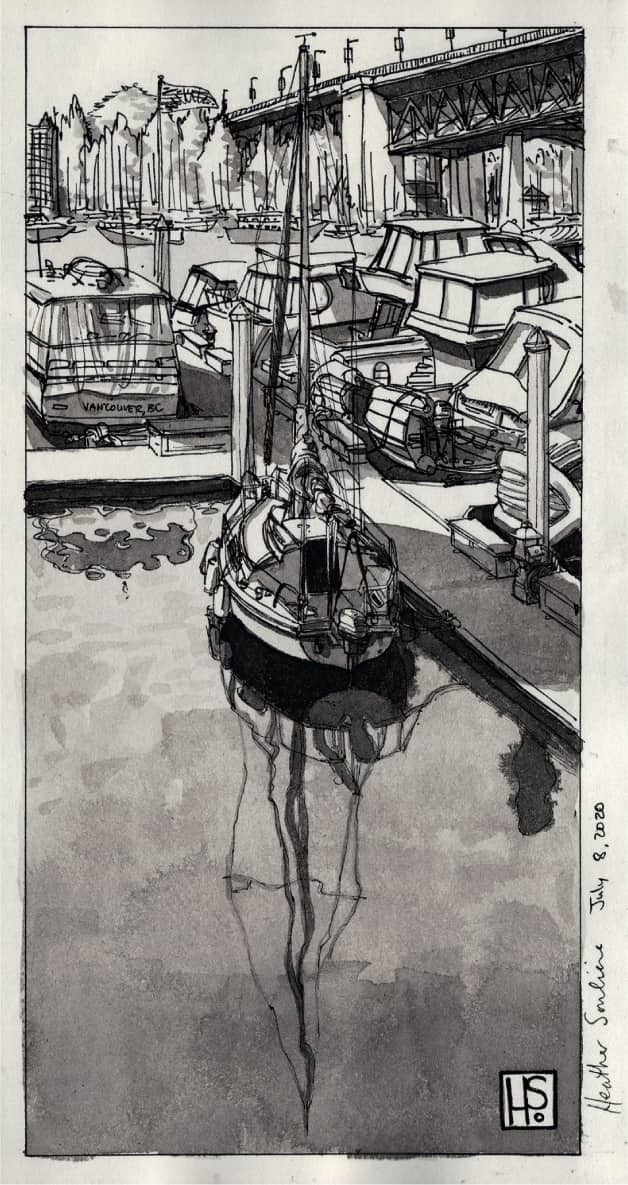

HEATHER SOULIERE

Boats on False Creek, Vancouver, Canada

3¼" x 6½" | 8.2 x 16.6 cm; HB pencil, eraser, Speedball Super Black India Ink mixed with water, Sakura Micron pen size 01; 45 minutes

Here you can see Heather captured a really clear reflection, with just enough wobble in the lines to show the viewer that the water isn’t perfectly still! Note how this reflection differs from the one in the windmill sketch, and how that affects our perception of the movement in the water.

Gallery: Reflections

ALEX HILLKURTZ

Amsterdam Sunshine, Amsterdam, Netherlands

8" x 8" | 20 x 20 cm; ink and watercolor; 30 minutes

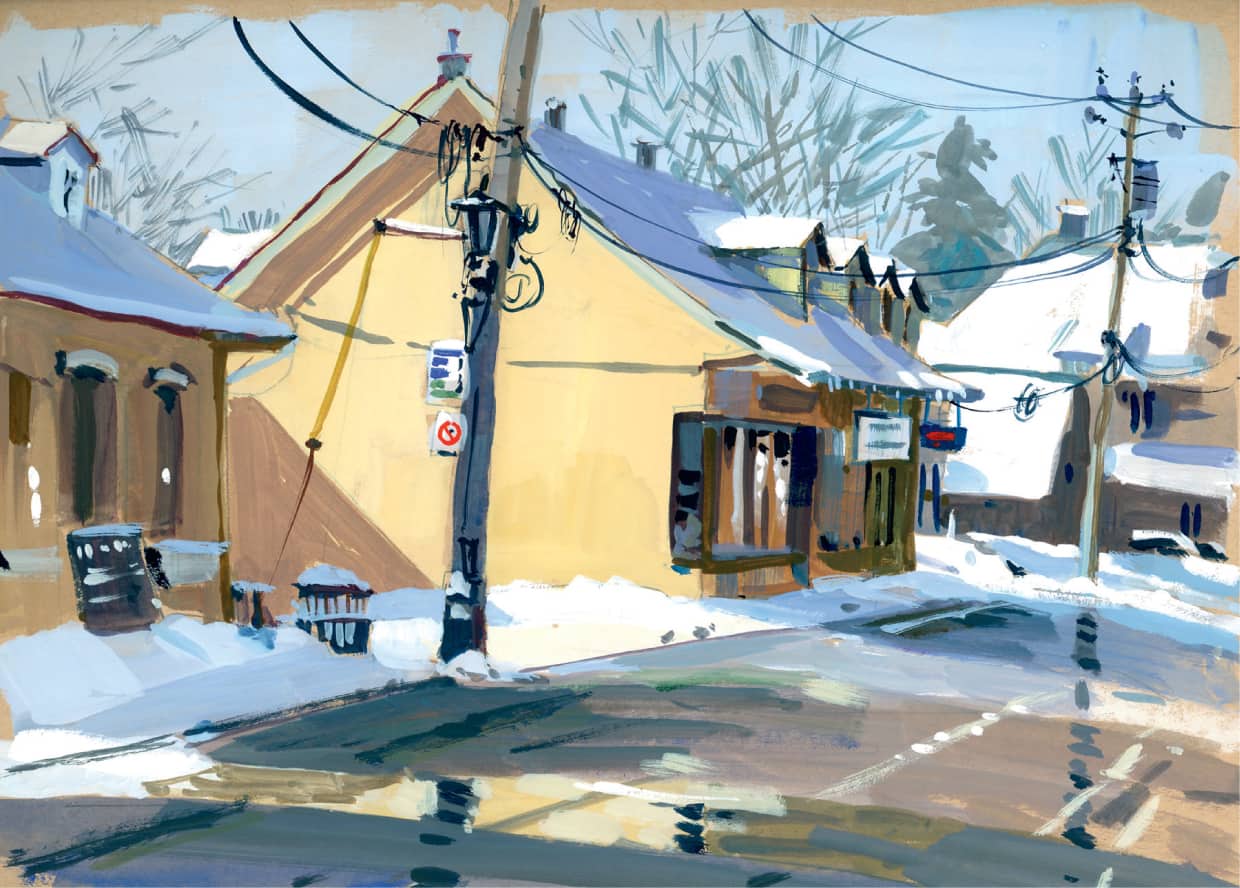

SHARI BLAUKOPF

Yellow Wall, Montreal, Canada

12" x 9" | 30.5 x 22.9 cm; gouache; 1½ hours

You may have an ocean, or just a shallow puddle. A reflection can be present no matter the depth of the water.

BHUPINDER SINGH

Fall Around Wascana, Saskatchewan, Canada

12" x 16" | 30.5 x 40.64 cm; watercolors and pencil; 1½ hours

MIKE KOWALSKI

Norwegian Wood, Port Townsend, Washington

9" x 12" | 22.9 x 30.5 cm; watercolor; 1 hour

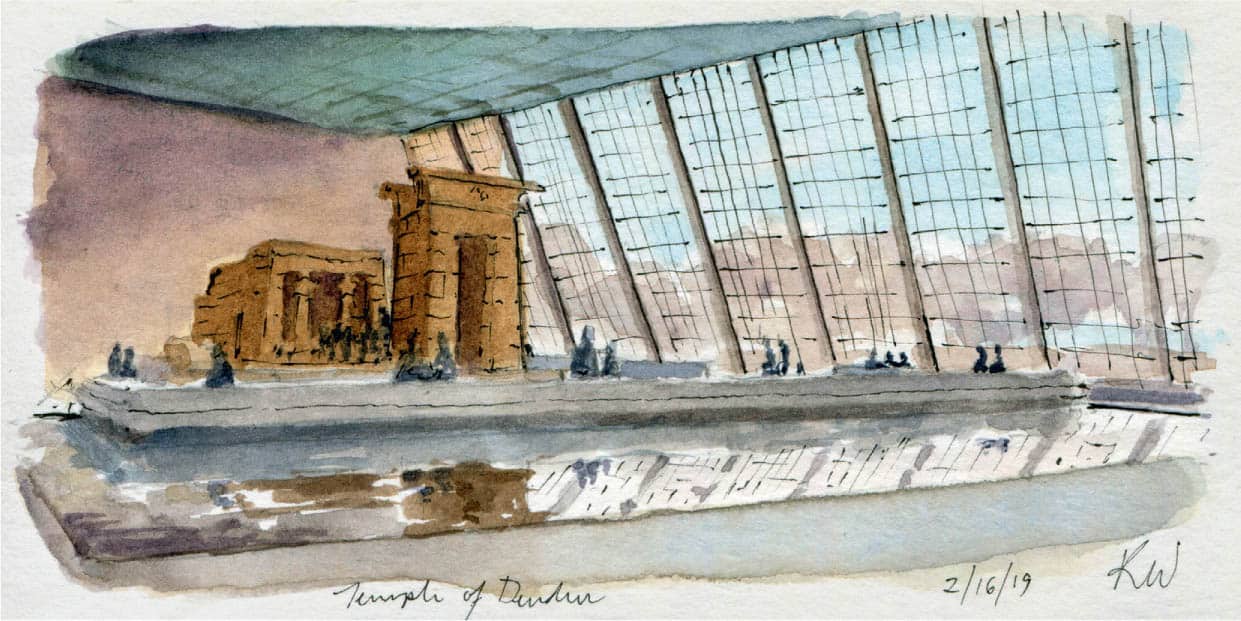

KATIE WOODWARD

Temple of Dendur, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

3" x 6" | 7.6 x 15.2 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, Pigma Micron pen

When seeing an object floating in water at a distance or when your eye is closer to the water level, the reflection may be a perfect mirrored image. If looking at an object at a steeper angle, from overhead, you will likely see the underside of the object, and a shorter reflection. Reflections can appear longer and stretched when on a less smooth surface, like moving water with ripples.

Reflections hinge on where an object meets the water. Far away objects that don’t touch your reflective surface hinge on where they would hit the surface if it continued and intersected with them. Sound complicated? Don’t worry, you don’t need to do math. When in doubt come back to observation. I have utilized the “fake it ’til you make it” approach to reflections, as they are something that can often have undefined edges and aren’t the full focus of a sketch, making it the perfect thing to fake.

FLOOR AND CEILING REFLECTIONS

Reflections don’t always appear in the most expected places. We expect to see them in mirrors, windows, and water, but they can also appear on floors, or glossy tiled ceilings. Maybe it has recently rained and there is a thin layer of water on the asphalt, or maybe you are looking at a recently buffed museum floor. This type of reflection can be fun both to replicate and to imagine and include in a sketch, even if you don’t see it in front of you. The reflection may be dull and undefined, or it may be an exact copy, depending on the surface you are seeing (or, what makes sense for your sketch.). When in doubt, look at the edges of the reflection to guide you.

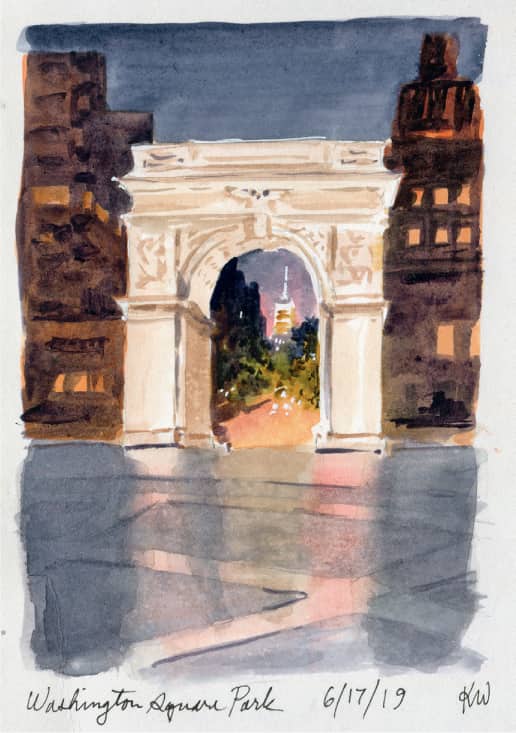

KATIE WOODWARD

Bison and Pronghorn, American Museum of Natural History, New York City

5" x 7" | 12.7 x 17.8 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, white Uni-Ball Signo gel pen, Pigma Micron pen; 1½ hours

This shiny museum floor gave me a good excuse to add a reflection to my sketch. The sections of floor were divided by very reflective brass strips, so I used my white gel pen to add those in at the end (note the black pen used for the same strips outside the reflected area).

KATIE WOODWARD

Washington Square Park, New York City

5" x 7" | 12.7 x 17.8 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, white Signo gel pen; 1 hour

Gallery: Floor and Ceiling Reflections

DOUG RUSSELL

Visual Arts Building Hallway, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming

14½" x 11½" | 36.8 x 29.2 cm; Platinum Carbon Black ink in a fountain pen, white Signo gel pen, Iroschizuku Kiri-same gray ink in a water brush on brown Stonehenge paper; 3 hours

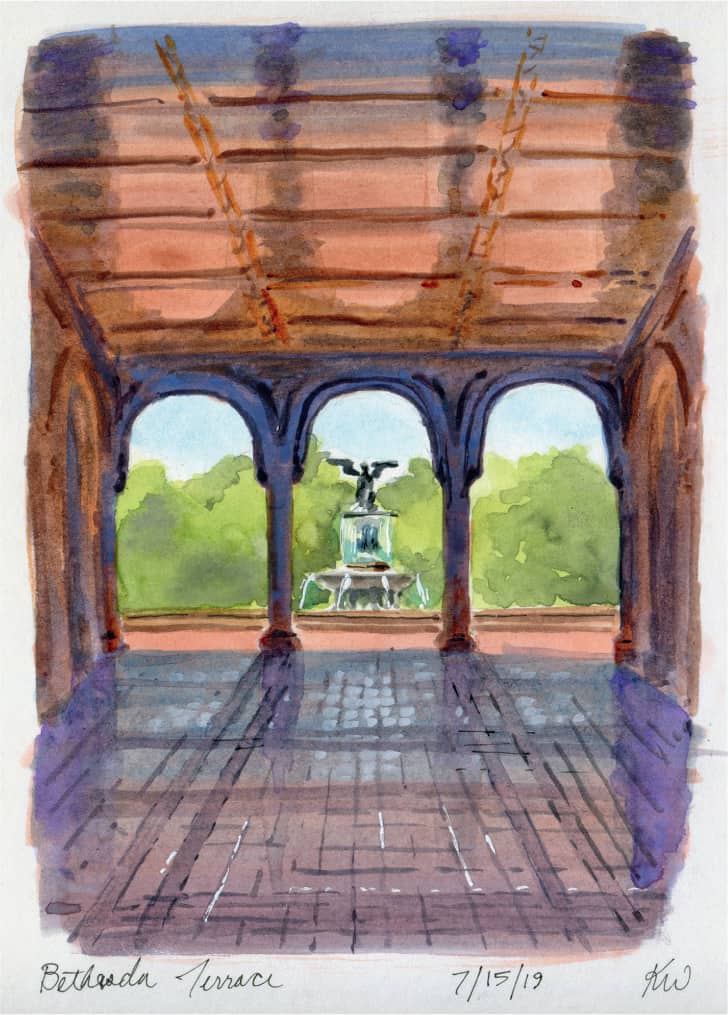

KATIE WOODWARD

Bethesda Terrace, Central Park, New York City

5" x 7" | 12.7 x 17.8 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, Pigma Micron pens, white Uni-ball Signo gel pen; 1½ hours

KATIE WOODWARD

Union Station, Washington, D.C.

6" x 8" | 15.2 x 20.3 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, Pigma Micron pens, white Uni-ball Signo gel pen; 45 minutes

WINDOWS AND GLASS

Cityscapes are often full of reflections; window glass provides a great opportunity to explore reflective surfaces. Some skyscrapers may be entirely covered in shiny surfaces, or you may just have small windows reflecting light. Let’s start with observation.

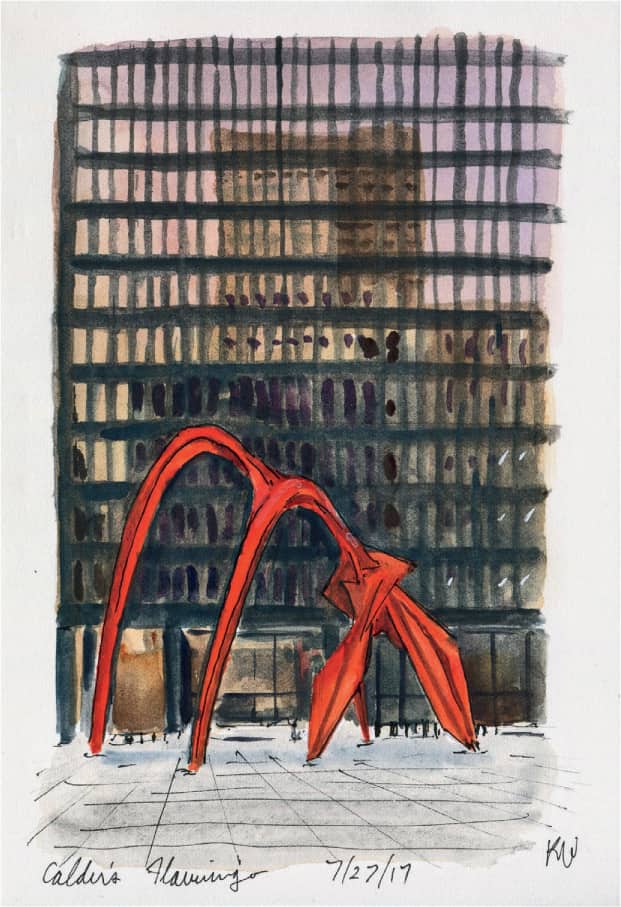

KATIE WOODWARD

Calder’s Flamingo, Chicago, Illinois

4" x 6" | 10.2 x 15.2 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, Pigma Micron pen; 30 minutes

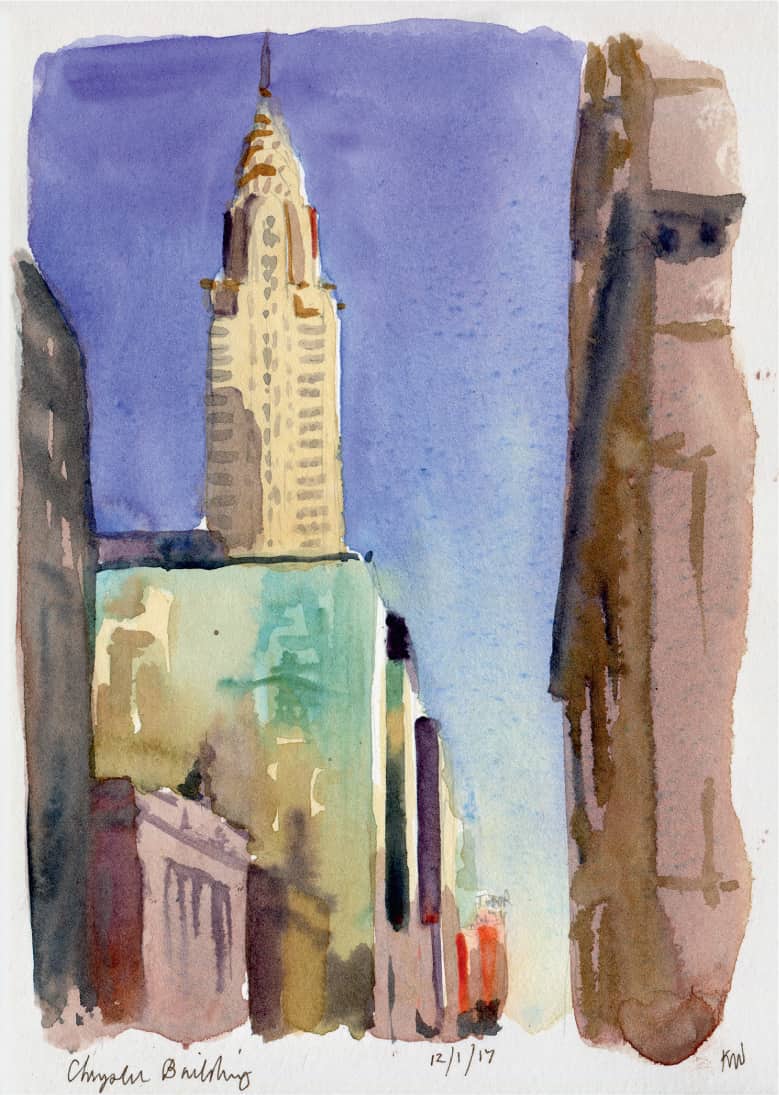

KATIE WOODWARD

Chrysler Building, New York City

5" x 7" | 12.7 x 17.8 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil

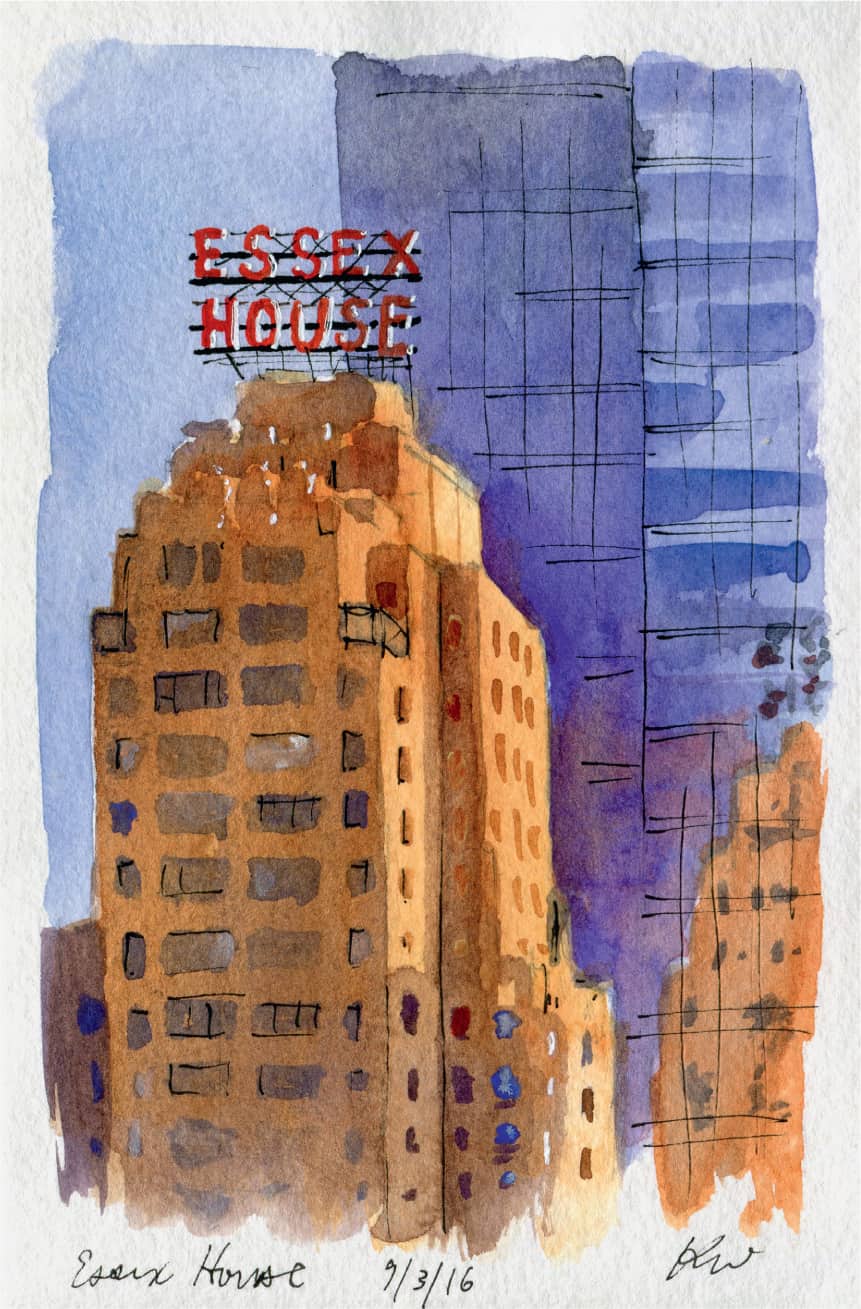

KATIE WOODWARD

Essex House, New York City

4" x 6" | 10.2 x 15.2 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, Pigma Micron pen, white Uni-ball Signo gel pen

Here, light was hitting the opposite side of Essex House, while the building beyond it reflected that brightly lit side back at me.

Observation Checklist

What color is the window?

What color is the window?

Is the window lighter or darker in value than the wall it sits in?

Is the window lighter or darker in value than the wall it sits in?

Are the reflections in the windows uniform, or varied?

Are the reflections in the windows uniform, or varied?

Do I see shapes of anything reflected clearly in the surface? Can I figure out what is being reflected?

Do I see shapes of anything reflected clearly in the surface? Can I figure out what is being reflected?

Can I see anything through the glass, on the inside of the window?

Can I see anything through the glass, on the inside of the window?

Even when you aren’t doing a closer study of a window, you can use reflections of far-off windows in your sketches. Some may reflect sky or nearby objects and appear as different colors from a distance. When dotting in windows, changing color or value can help add a nice detail and texture to a sketch. I sometimes call this visual noise—something that just adds a little detail and interest to a sketch but doesn’t necessarily require a lot of work. You never have to match window for window what you see, but just taking a second to observe can inform that choice. On a part of a building in shadow, a window may still be reflecting sky and be seen as a pop of light on an otherwise dark wall. The same idea can be used in night sketches to show windows that are on or off (or, are lit with different types of light). In lieu of reflections, windows may look different whether they are open or closed or have different colored curtains! Little things like this can help give life to a sketch, and give a better sense of lighting, with very little effort.

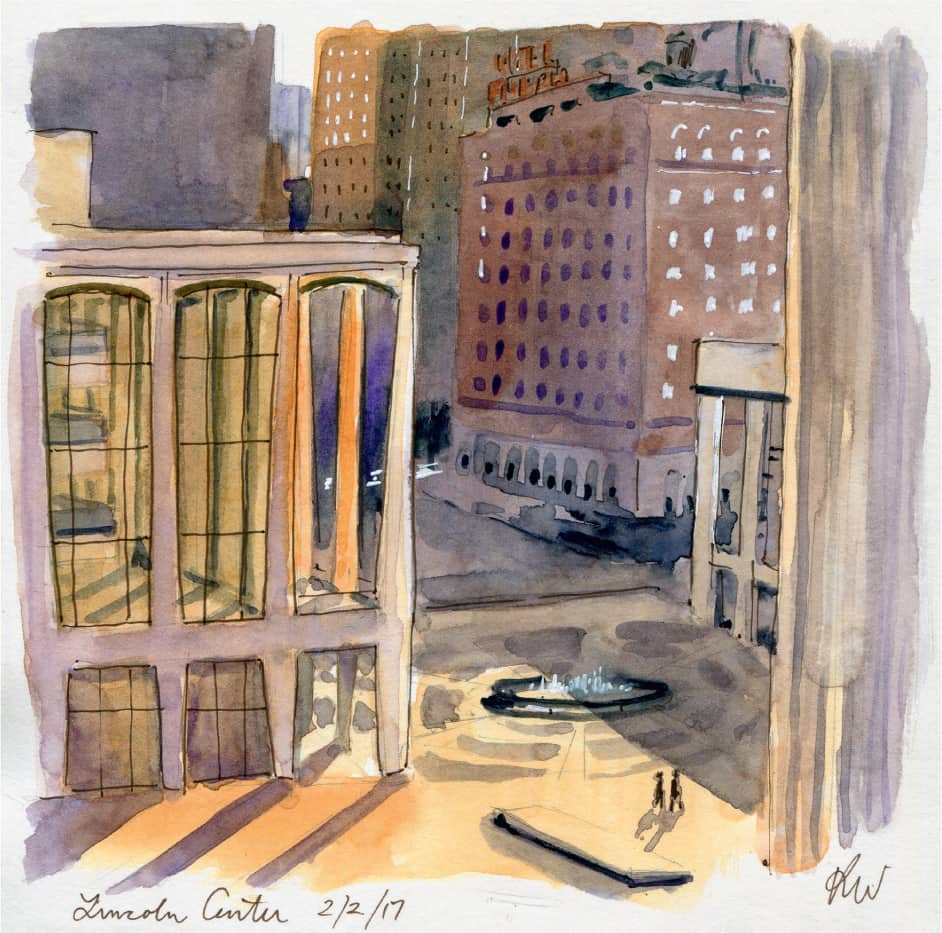

KATIE WOODWARD

Lincoln Center, New York City

6" x 6" | 15.2 x 15.2 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, white Uni-ball Signo gel pen, Pigma Micron pen

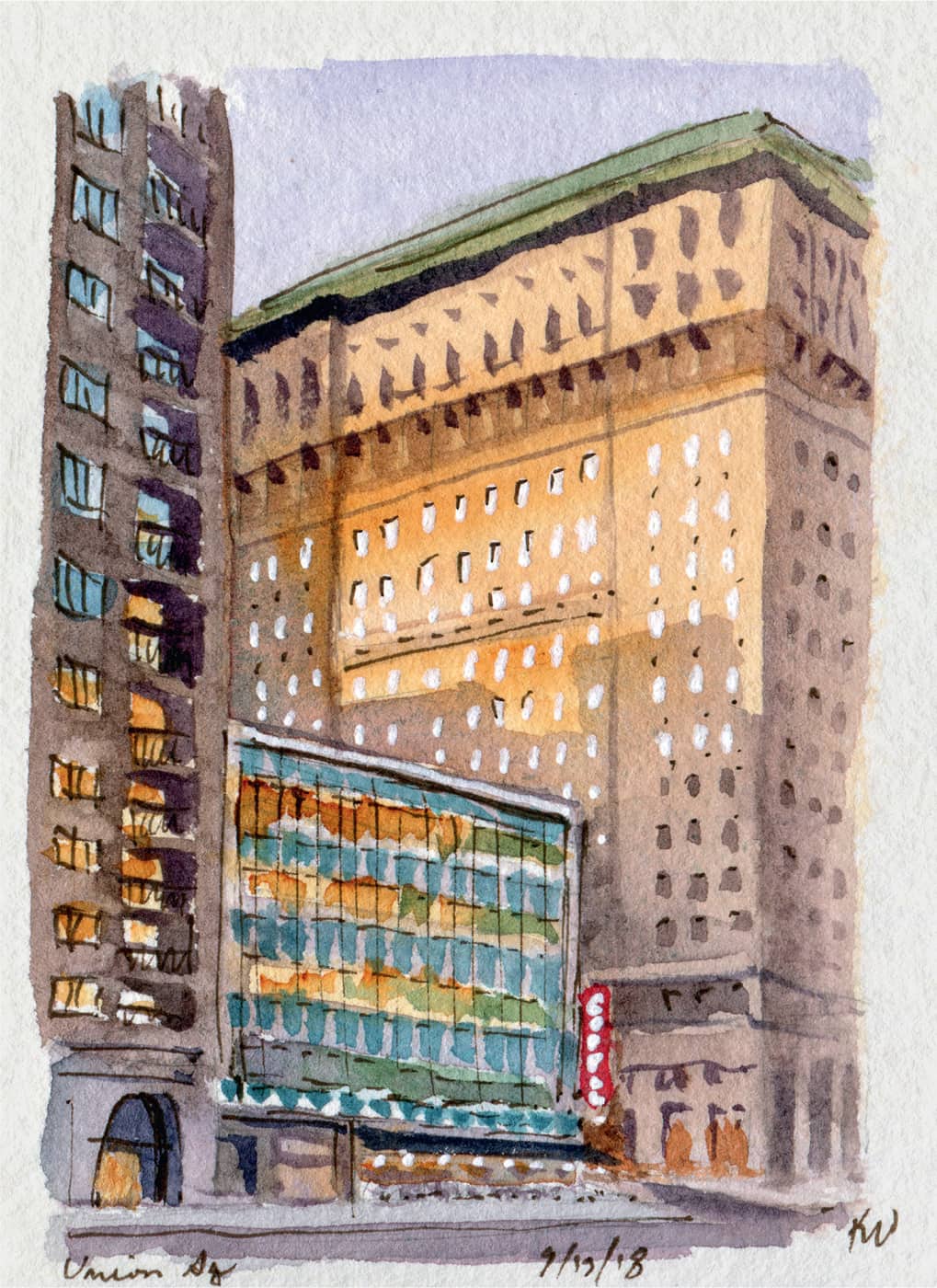

KATIE WOODWARD

Union Square, New York City

3" x 4" | 7.6 x 10.2 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, white Uni-ball Signo gel pen, Pigma Micron pen; 1 hour

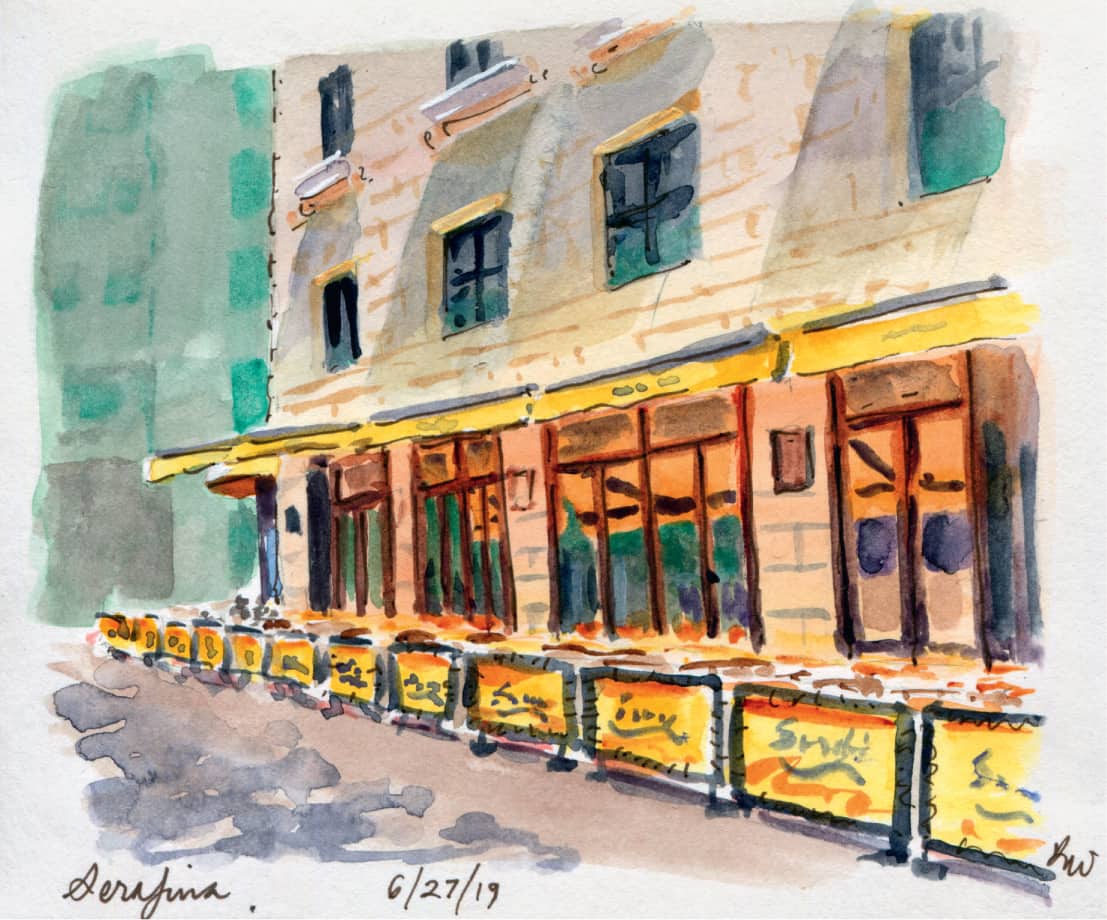

When observing windows up close, we sometimes see full reflections and other times we just see through to the interior. Often, it’s a mix of both. I usually take a minute to piece together what I’m seeing: Is it reflection, or is it interior? If I’m seeing a reflection, I start by trying to figure out what is being reflected.

KATIE WOODWARD

Serafina, New York City

5" x 6" | 12.7 x 15.2 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, white Signo gel pen, Pigma Micron pen; 1½ hours

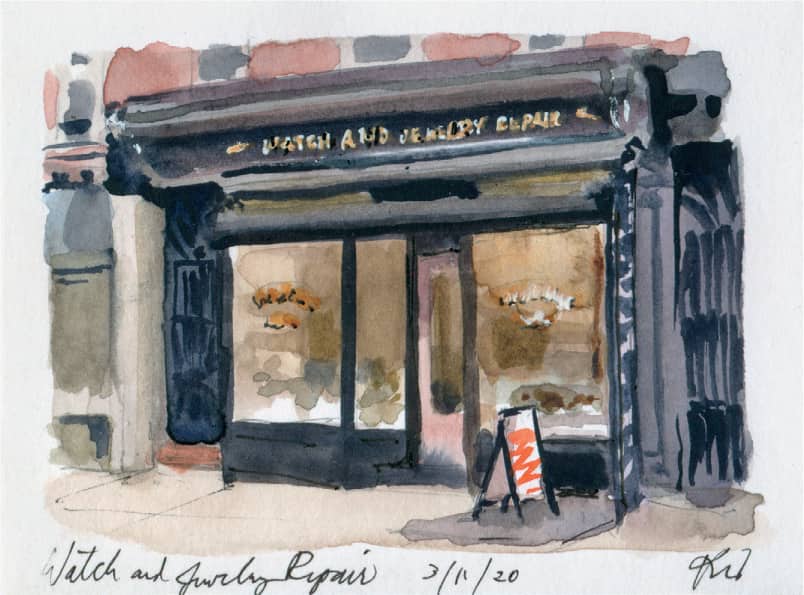

KATIE WOODWARD

Watch and Jewelry Repair, Brooklyn, New York

3" x 4" | 7.6 x 10.2 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, white Uni-ball Signo gel pen; 30 minutes

How bright the reflection is affects how much you can see through the window. Since the reflections on this window were very soft, you could mostly see what was inside through the window.

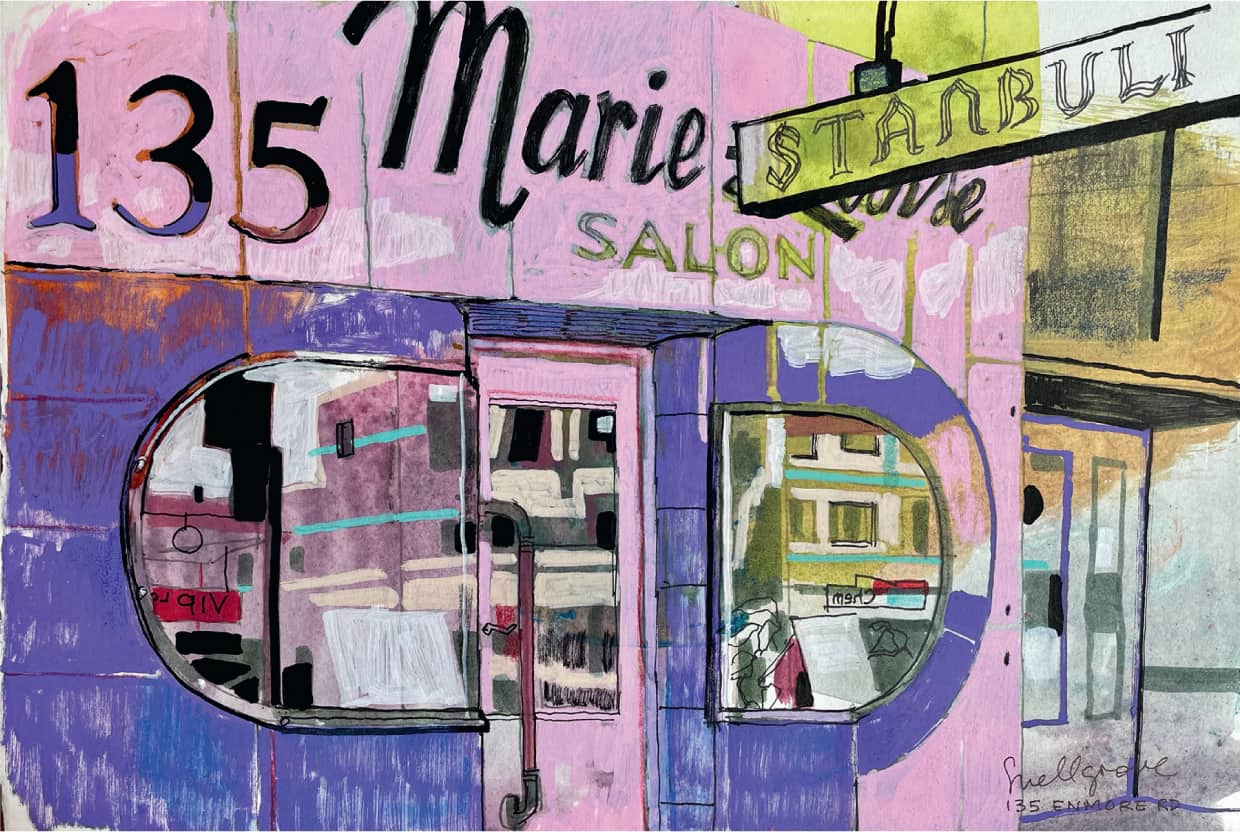

ALEX SNELLGROVE

Hair and Beauty Salon, Enmore Road, Sydney, Australia

8¼" x 11¾" | 21 x 29.8 cm (A4); markers (Posca, Tombow, Fineliner) and watercolor pencil on a prepared acrylic background (not made specifically for this purpose); 1½ hours

“This landmark shop is now a Turkish restaurant but all the original features are intact. Most Sydneysiders have a soft spot for the garish pink and purple enamelled shop facade on busy Enmore Road, and I found it irresistible. The background was brown, lime green, yellow ochre, and other dull colors. You can see traces of it in the top right corner and in the window reflections. The other side of the street was sunny, but I was in the shade.”

—Alex Snellgrove

REFLECTIVE OBJECTS

Reflections on sculpture and other three-dimensional objects can be especially fun to render! Reflections can tell the viewer about the shape of an object. Musical instruments are a great example of this. Depending on the level of shine of the object, this may be anything from a soft highlight to indicate a subtle shine, to a full, detailed colorful reflection of the object’s surroundings. Reflections, like shadows, can help give an object in a sketch volume to visually sculpt a scene.

MIKE KOWALSKI

Vic and His Tuba, Port Angeles, Washington

7" x 10" | 17.8 x 25.4 cm; watercolors; 30 minutes

Note the skin color used in the reflection facing the musician. The sharp reflections we see on the tuba, coupled with the use of colors that appear on the musician, tell us that the instrument has a very shiny, mirrored surface.

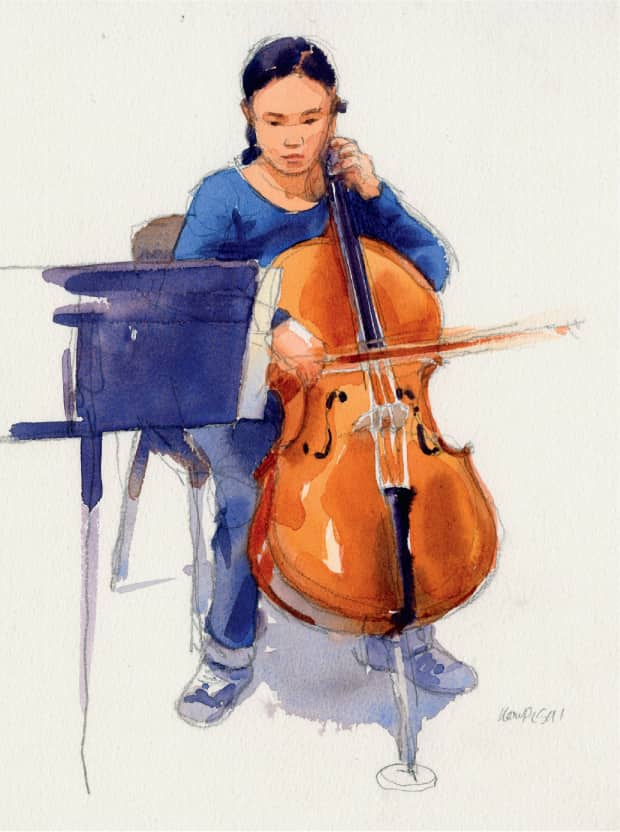

MIKE KOWALSKI

The Cellist, Seattle, Washington

7" x 10" | 17.8 x 25.4 cm; watercolors; 30 minutes

Here, the reflections are much more subtle than on the mirrored brass of the tuba, but you can still tell that the cello has a very shiny coating. For objects that are shiny, but not mirrored, you will most likely see the nearby points of highest contrast reflected, like highlights from nearby light sources.

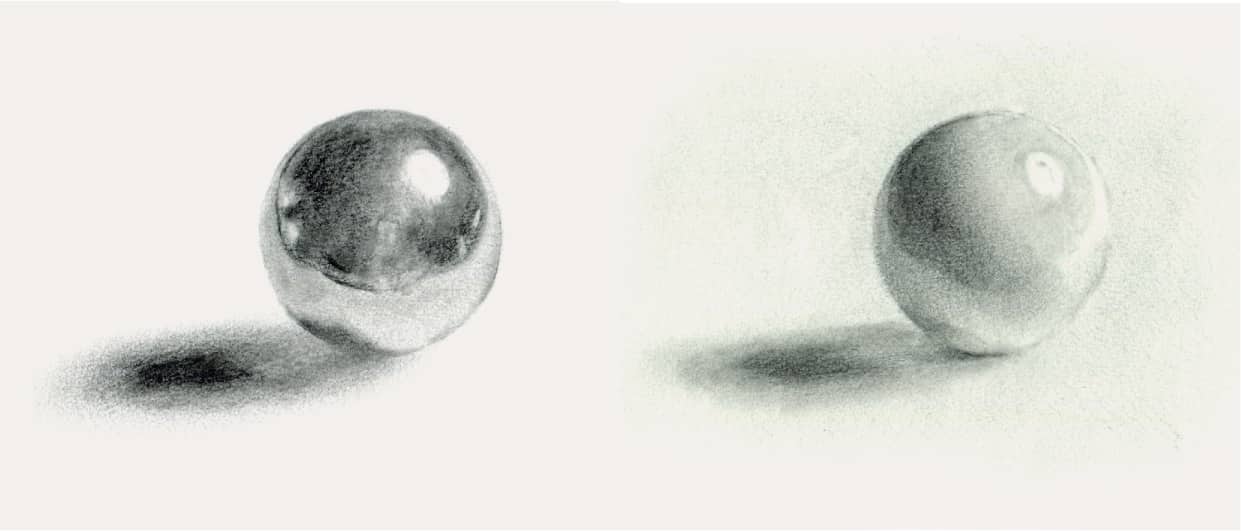

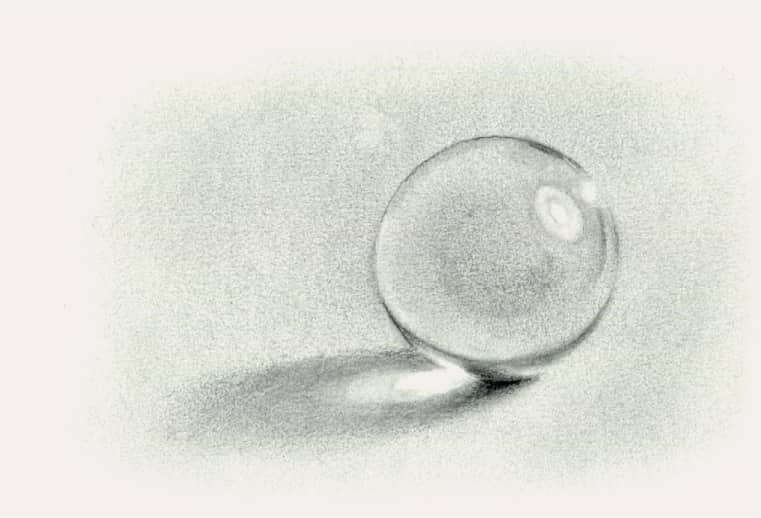

Note that on this shiny white cue ball, you still see the light source reflected, and the high contrast area of the edge of the white table, but most of the details seen on the mirrored ball are obscured.

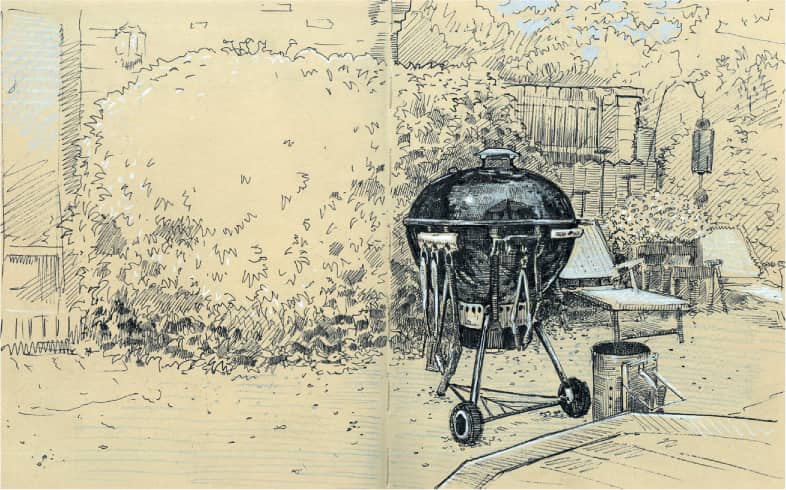

DOUG RUSSELL

Labor Day Back Yard, Laramie, Wyoming

10" x 16" | 25.4 x 40.6 cm; Platinum Carbon Black ink, Prismacolor pencil in a beige Stillman & Birn Nova sketchbook; 2 hours

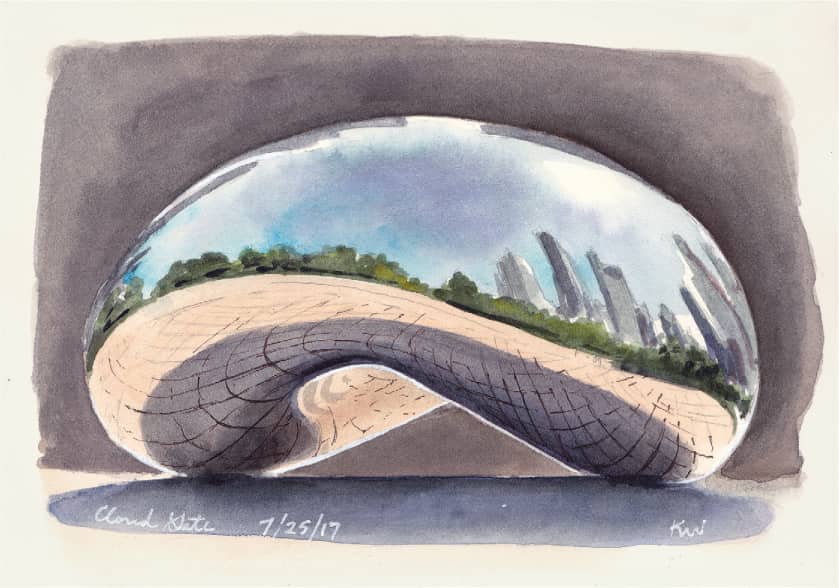

KATIE WOODWARD

Cloud Gate, Chicago, Illinois

5" x 7" | 12.7 x 17.8 cm; watercolor, graphite pencil, Pigma Micron pens, white Uni-ball Signo gel pen

Here you can see how the shape of the sculpture bends the shapes of the reflections. The buildings are compressed together, and the grid of the pavement conforms to the shape of the bean.

TRANSPARENT OBJECTS

Flat windows, while made of glass, sometimes miss out on a fun aspect of shaped glass or water: refraction. Light bends as it travels through a glass shape (or liquid) and can come out in unexpected ways; we still see shadows, but we can also get more focused light. Often, translucent objects are also reflective, which means you have to consider how reflective they are in addition to what you are seeing through them.

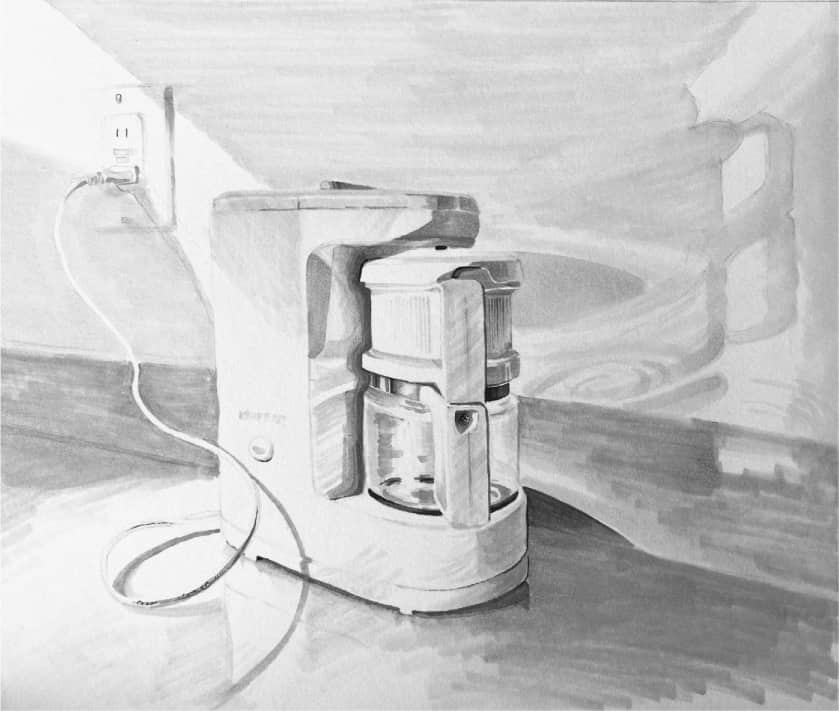

SUE YEON CHOI

Waiting for Morning Coffee, San Francisco, California

9¼" x 10¾" | 23.4 x 27.4 cm; pencil, Copic Sketch Markers in Neutral Gray N0, N2, N4, N6; 1 hour

As light filters through glass, you will still see a shadow, but it won’t be solid as you would see with an opaque object. Areas where the glass is thicker will be darker, while other areas may leave no shadow at all. Light filtering through the glass gets refracted and may come out in unexpected places.

ANITA ALVARES BHATIA

Floating Tomatoes, Mumbai, India

7" x 6" | 18 x 15.5 cm; pencil and watercolors; 1½ hours

KATIE WOODWARD

Sweet Tea, New York City

7" x 9" | 17.8 x 22.9 cm; graphite pencil, watercolor

KATIE WOODWARD

Freemans, New York City

5" x 8" | 12.7 x 20.3 cm; graphite pencil, watercolor, Pigma Micron pens, white Uni-ball Signo gel pen