4

Communicating with Different Personality Types

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• Explain the preferences of the different Myers-Briggs personality types.

• Indicate how the different personality types communicate and deal with information.

• List the key areas in which personality type differences create communication difficulties.

• Identify things you can do to make communication between different personality types more effective.

PERSONALITY DIFFERENCES

Many breakdowns in communication are attributed to the problem of “personality differences.” That diagnosis is often followed with this advice: “And since you can’t change someone’s personality, you’d better resign yourself to a bad working relationship or get out.” The word “personality” and the term “personality type” have many popular and sometimes contradictory definitions in current usage. This chapter is not designed to go into a psychological discussion about what aspects of personality are inborn and which develop as a part of life experience. However, this chapter does make certain assumptions:

• Different personality types have different communication preferences.

• A failure to recognize and accommodate those differences can lead to communication difficulties, resulting in a drop in productivity and an increase in general workplace tension.

• The key factors in getting the best from differences are appreciation, understanding, and adaptability.

• Although personality is unchangeable, workplace behavior is changeable; behavior can be adjusted to benefit the organization and oneself.

The major reason that personality differences so adversely affect workplace (and other) relationships is each individual’s assumption that his or her own personality is the best one. “If more of my coworkers were like me, the office would be a better place—certainly it would have better communication.” Consider some of the ways in which personality judgments are used negatively:

“Well, you know the type I’m talking about.”

“He has no personality—he’s the uncommunicative type.”

“Given her personality, don’t expect much enthusiasm from her.”

“He has too much personality for this office.”

Each of these comments contains prejudices about what personality is and how it affects a person’s behavior. Yet most of us indulge in this kind of judging at one time or another. The preceding statements betray an underlying feeling that “our” personality is best, and that the value of other types can be assessed only in their proximity to ours.

The truth is that personality differences often lead to more productive offices, departments, and teams. Having many different personality types involved on a project “covers all the bases” more thoroughly. It brings a variety of strengths to the work.

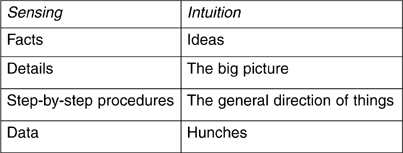

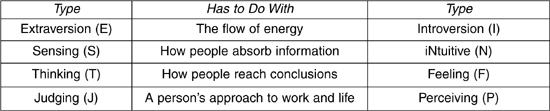

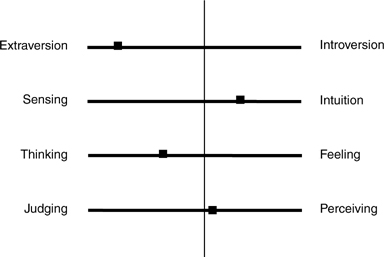

Many businesses use the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® (MBTI) to understand personality and preferences with respect to communications, decision making, and group-based work. Roughly two million MBTI tests are administered each year in the United States. MBTI was developed in the early 1940s by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers. They were influenced by Carl Jung’s theories of personality types. In a nutshell, MBTI establishes four opposing pairs, or dichotomies, of personalities, as shown in Exhibit 4–1.

Each pair of opposing types focuses on one aspect of personality. As shown in the exhibit, extraversion versus introversion tells us about how people generate energy. The second pair, sensing and intuitive, provide clues as to how individuals absorb information—a very important thing to understand when effective communication is your goal. Thinking and feeling describe preferences for reaching conclusions. And the last pair, judging versus perceiving, reveals much about a person’s preferred approach to making decisions in work and life.

Depending on how a person answers the lengthy MBTI questionnaire, he or she receives a four-letter “reported type,” such as ESFP. Each letter in the score represents the person’s preference within each of the four opposing pairs. For example, an ESFP person’s preference would be stronger in extraversion, sensing, feeling, and perceiving than in introversion, intuition, thinking, and judging. If you do the math, you will see that there are sixteen possible combinations, or reported types. But what do these letters mean?

Extraversion/Introversion

Of the four opposing pairs, extraversion versus introversion is the most familiar and straightforward to most people. We think of introverts as reflective people of few words who aren’t particularly outgoing. Extraverts, on the other hand, are big talkers and outgoing; they like being around other people. Myers-Briggs is more subtle in assessing these types. According to MBTI doctrine, people with a preference for introversion are reflective; they think about information and develop plans before discussing them with others. Given a choice they will focus inwardly on ideas and impressions. They internally process the information they receive from others before making a move. Reflection builds their energy.

Extraverts, on the other hand, process information through conversations with others. Unlike introverts, they look outward to the world. They are energized through contact with others and are de-energized when they must go off and reflect by themselves. For example, after an intense two-hour meeting, extraverts will emerge energized while introverts will feel depleted.

You’ve probably known people who, to one degree or another, reflect these two personality types. Here are two prototypes:

William in accounts payable is the introverted type. He is very good at processing information and producing error-free work. He doesn’t say much at meetings unless someone asks his opinion. Before he offers an idea, though, he thinks it through. He’s most comfortable when he is at his PC working on financial spreadsheets and developing reports.

Constance, on the other hand, is an extravert. She gets restless and bored if she must sit at her PC and labor over a long report. She’s more interested in talking with people over the phone, taking customers to lunch, and discussing plans and ideas with them. At meetings, no one has to urge her to speak up; she would dominate the conversation if given the chance. When Constance gets an idea, she doesn’t sit down and think it all through; instead, she is quick to bounce it off others and get their reactions.

Sensing/iNtuition

The sensing person in the Myers-Briggs world is very oriented to the present and prefers to work with concrete, factual information accessed through—you guessed it—the senses: market research, financial statements, inventory counts, and so forth. A person with an S preference looks for details and facts. His or her intuitive counterpart, the N preference type, is future-oriented and is more open to its possibilities. This person is more comfortable than the S person with fuzzy, ambiguous situations based on abstract ideas or theories. We’d expect many product developers, business strategists, and salespeople to have strong N preferences.

Thinking/Feeling

Thinking (T) types are rational and analytical in how they approach decisions and problems. If they are shopping for a new car they will use an objective approach. “What does Consumer Reports testing say about this make and model?” They will make careful comparisons with alternative choices. T types can separate themselves from situations and assess them with detached objectivity.

A feeling type (F) person is less likely to detach himself. His feelings and personal values play a role how he approaches important choices. When he is buying a car, for example, he may check Consumer Reports ratings, but his gut feelings about alternative cars also matter. In making a decision he will try to harmonize his final choice with his feelings and personal values.

Judging/Perceiving

These terms are the most confusing in the Myers-Briggs vocabulary. They do not imply that one person is judgmental while the other is mentally perceptive. Instead, a J person prefers a situation that is planned out and settled. A J person likes things to be unambiguous and is comfortable making decisions. On the job she prefers a clear work plan with milestones that can be checked off as completed, and a deadline. If her boss asks her to put a project aside and work on something else, she may say, “I’d prefer to first finish what I’ve started.”

A perceiving type, one the other hand, will feel comfortable setting aside that current project to pick up another. Ps are more flexible and spontaneous in their approach to life and business. While our judging person would say, “We need to plan out the steps of this project and then get started,” the perceiver would reply, “No, I’d rather get started and see where the project takes us. We can always make adjustments later.” A P person will often hold off making a final decision and gather more information.

One important thing to remember about the Myers-Briggs system is that none of the opposing types is better than any others. They are merely different. Extraversion is not better than introversion. Nor is any person a pure type. William, our introversion example, for instance, probably has some extravert traits just as Constance is likely to have some introvert traits. On balance, however, these individuals fall into one side or the other of the introversion-extraversion continuum. In fact, the Myers-Briggs test questions try to determine where an individual falls along each of the four continuums. Exhibit 4–2 is a hypothetical report on Constance. Notice that she has strong extraversion preferences, mild intuition and thinking preferences, and that she just barely falls into the perceiving category. Probably no one is a “pure” anything in the world of Myers-Briggs. As one of the authors likes to say, “I’m an introvert with good extravert skills.”

PERSONALITY TYPES AND COMMUNICATION ISSUES

Now that you understand the basics of personality types, as categorized by Myers-Briggs, you may be asking, “What does this have to do with interpersonal communication in the workplace? The answer is ‘Quite a bit’.”

According to Sandra Hirsh and Jean Kummerow, authors of LifeTypes: Know Your Personality Type, the Myers-Briggs research indicates that personality affects communication in the workplace in two major ways:

1. What a person pays attention to when gathering and giving information

2. What criteria a person uses to make decisions and prioritize work

It’s helpful to know your own personality type, particularly in these two areas, not to put a label on yourself, but to help you understand your preferences as a person and as a communicator. Preferences simply indicate what you would choose given options that are discernibly different. For instance, most of us have the full use of both hands, but generally we have a preference for right or the left when writing, playing sports, and so forth. In much the same way, there are preferences built into your personality. This does not mean you are locked into them. You can adapt and change. In fact, as an employee you must be adaptive if you want to be an asset to your organization and advance in your career.

Now that you understand and appreciate the differences between individuals, you must adapt to these differences in workplace settings. This is not to say that you need to have a personality makeover. Instead, learn to adjust your communication to fit the situation and thus contribute to higher productivity. For example, if you have determined that you are a feeling type and you interact with a thinker on a regular basis, you do not have to “become a thinker” to communicate with that coworker. But you will have to put your “feeling” perspective in terms that a thinker will respond to positively.

Knowing something about your preference for giving and receiving information and about making decisions can help you when you communicate with your boss, teammates, customers, and coworkers. And if you recognize the preferences of these other people, you’ll be able to adapt in ways that make your communications more effective. Let’s return now to each of the opposing personality types and reflect on what they mean for your ability to communicate effectively.

Your preferred style should never be used as an excuse for not doing your job. If you are high on the introversion scale, that is no excuse for avoiding dialogue with coworkers, customers, and others with whom direct interaction is required by your job description. The same goes for extraverts who must periodically gather and reflect on facts before springing their ideas on other people. Leopards cannot change their spots, but people can adapt their behavior when situations require it.

Can you identify any situations at work where you’ve needed to adapt your behavior to meet the needs of others or fulfill the requirements of your job?

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Communicating with Extraverts and Introverts

As noted earlier, extraverts like to interact with others. They love to talk and bounce their ideas off the people they meet. They’re the people who pop into your office and ask, “What do you think of this idea?” If they must give a presentation to the sales force, they don’t dread it; they actually look forward to getting up there and talking. And they seek feedback. “How many of these do you think we can sell this year?”

To communicate with an E person, approach her in her preferred style—which is verbal. She doesn’t want to read through a five-page report to find out what you have to say. She doesn’t want to do business through an exchange of emails, which is a poor substitute for face-to-face dialogue. Remember, this person likes interacting with people, so communicate in a way that engages that preference.

Now consider the introvert. The I person likes a quiet place to concentrate and develop ideas and generate energy. In an era that glorifies multitasking, he prefers focusing on one task at a time. He is less interested in a team project than in one he can handle alone. If your boss is like this, he’d probably prefer a full written report he can absorb at his leisure to a rapid-fire conversation with you in the hallway. Having a boss like this may be difficult if you are an extravert! But remember, extraversion is merely a preferred style—not the only style a person can handle.

People with diametrically opposed preferences can actually communicate and work together very well when they understand each other, and when their differences complement one other in positive ways. Here’s an example. Anne, a strong I person, works very productively with Paul, a client who is a solid E. Paul, the president and founder of a small publishing company, is an exuberant individual who loves nothing more than meeting with writers, discussing their ideas for new books, verbally rallying the office staff, and acting to get projects underway. Someone, of course, must guide each of those projects through to completion—a chore that involves substantial concentration, reading, and solitary work—which is one of Anne’s preferred styles. Thus, her introversion and Paul’s extraversion complement each other and support the work effort.

Communicating with Sensing and iNtuitive Types

Sensing and intuition in the Myers-Briggs world is about how people take in information and the types of information they trust. Here, we have a case of the head versus the gut. Sensing people gather information through their senses; their preference is for information they can see or touch. Intuition-oriented people are more reliant on their gut feelings for things. They pay attention to the unseen world of meaning, connections, inferences, and hunches. Communications problems are common when sensing and intuition people are brought together. A classic example is when sales people cross paths with financial people. Sales people tend to be optimists and live in a realm of possibilities, not solid facts. Is there hard-and-fast evidence to support the sales forecasts they routinely submit to their companies? Hardly ever. Yet they will say, “There’s a good chance that XYZ Company will give us the contract.” And they may be right because they are sensitive to intangible signals. Financial people, who deal in hard numbers, will ask, “What do you mean by ‘a good chance?’ Where did that come from?” All that the sales person can offer is, “That’s my gut assessment of where we stand with that sale.”

Interactions like these contain potential conflicts. The finance people who provide the resources to produce goods and services for customers in the months ahead cannot be satisfied with hunches. They don’t want to build costly inventories of goods that will sit on the shelf with no buyers. On the other hand, the sales people cannot predict the future. The sales people, however, can be more effective communicators if they recognize the preference of their colleagues for tangible data; and the financial people will find communications with the sales force more productive if they understand the preferences of those individuals. They might, for example, seek a middle ground.

Financial manager: “If you think there’s a good chance of the sale to XYZ Company going through, could you try to quantify that possibility?”

Salesperson: “What do you mean?”

Financial managers: “Well, based on what you know now, would you say that there’s a 50-50 chance of getting the sale, or something like that?”

Salesperson: “Oh, I see what you mean. Right now I’d say there’s a 75 percent probability of our making the sale.”

In this example the two parties have helped each other. The sales person has translated his hunch into the kind of information that the financial manager prefers and can use.

Bringing sensing and intuitive people together can produce real benefits. The sensing people are a valuable check on the idea- and hunch-oriented intuitive people, and inject some rigor to discussions about future plans. If someone is offering unsupported ideas, the S people will challenge that person: “Where’s your evidence for that?” Intuitive people, for their part, add the imagination and big-picture outlook that detail-oriented sensing people so often lack. Each has a strength that potentially complements the other’s weakness.

Communicating with Thinking and Feeling Coworkers

Thinkers prefer logical, objective analysis; they lead with their heads. Feeling people seek harmony and are concerned with relationships; they lead with their hearts. Because of these preferences, Ts and Fs often have great difficulty in communicating on important decisions. Imagine two business partners contemplating the purchase of an office condo for their small firm. The T partner is focused on the financial aspects of the plan. “How will the mortgage payments affect our budget and monthly cash flow? Is the space a good investment at this price? Should we hold off until interest rates go down?” The F partner, on the other hand, is wrapped up with all the good things the new office will do for the company. The F partner is already picturing the favorable reaction of visiting clients, and how the employees will love their new workspaces. In this case, T and F are on very different wavelengths. Unless each makes an effort to understand the other’s concerns, they will have trouble communicating. One approach to solving this problem is to have an agreement: No decision will be made unless both parties are happy with it. Alternatively, one could make the decisions in situations that are highly quantitative, while the other would rule on qualitative matters.

![]() Exercise 4–1. The People You Work With

Exercise 4–1. The People You Work With

List three people you work with most often, including your boss. Now try to estimate where they would fall on the continuum from sensing to intuition. Mark the place with an X.

1. Name:

Sensing ______________________________________________________ Intuition

2. Name:

Sensing ______________________________________________________ Intuition

3. Name:

Sensing ______________________________________________________ Intuition

As you can probably recognize, there is great value in creating communication between people with thinking and feeling preferences. One can balance out the excesses or weaknesses of the other—but only if they will talk and listen to each other.

Communication Between Judging and Perceiving People

Judging and perceiving have a lot to do with how people prefer to work. J people like things well-planned and organized, while P people prefer flexibility, spontaneity; and having their options left open. This can cause problems when Js and Ps must work together. The Js will be pushing for a detailed plan to guide them. They prefer order, schedules, and clear goals, and will push for closure. “Can we agree on a plan so that we can get moving? Let’s wrap this up, OK?” The Ps, to the frustration of Js, are inclined to respond, “Let’s not rush things. Let’s keep our options open and see what develops. Perhaps we could talk about this again next week.”

Are you working now with J or P type coworkers? Which of those types are you? Each has much to offer the organization and each other in terms of complementary tendencies if you can get them communicating. For example, the J members of your team may be pressing for closure. “Let’s make a decision, adopt a plan, implement it, and move on.” Meanwhile, the Ps are likely holding out for more information and other possibilities. They will also try to improve the proposed plan or make changes to the plan in process. One solution to this type of impasse is to get people talking about what specific information is needed for the decision, and how that information can be acquired.

GENERAL GUIDELINES TO FOLLOW

The previous section highlights the difficulties typically experienced when people with opposing personality types try to communicate. And it offered suggestions for reducing those difficulties and reaping the benefits of personality differences. But be forewarned: neither of the opposing personality types will want to give ground. In fact, the natural tendency is to drag discussion further into one’s preferred preference area, which will only make matters worse. You will be more successful in communicating with different personality types if you follow these five guidelines: ask, collaborate, thank, speak the right language, and don’t pigeon-hole people.

Ask

Communication problems are often based on assumptions—some that we know we are making, others that we don’t. To break the assumption trap, find out what you don’t really know but may have been assuming erroneously. In short, ask. For instance, if you’re in a workplace situation that involves sending and receiving lots of reports and memos, ask, “How much detail do you prefer in these reports, and what form should the data take—anecdotal or facts only?” Or, if a project has been given to you, ask the person who assigned the work, “What specifically do you need from me?” This keeps the focus on the work. You’ll need that information to maintain a good working relationship.

Collaborate

Most successful work requires collaboration, with everyone putting forth his best effort to accomplish what no individual could have accomplished on her own. Personality differences can impede collaboration, particularly when many ideas are offered and a direction must be set. However, since collaboration involves getting everyone’s best efforts, pieces of the project can be divided up appropriately to take advantage of the personality differences. You might say, “I’m a really detail-oriented person; I’d be happy to handle the number-crunching for this project.” Or, “I am good at working with ideas; I’d be happy to summarize the ones presented today and get them to you before the next meeting.” This will encourage others to contribute their strengths too.

Thank

Too few people express their appreciation for other perspectives. Yet it can aid communication. A thinker might say to a feeler, “I hadn’t really thought of how that software change would affect others. Thanks for helping me to see it from their angle. We may need to offer training before they start using the new version.” Appreciation accomplishes two things: It reminds people that differences are good, and it encourages them to hear you out in the future when you offer a perspective different from theirs.

Speak the Right Language

Because personality type affects what we hear and how we hear it, you can improve the effectiveness of your communication with coworkers by adopting their language. This does not mean you become like them in all ways; it simply means delivering your message in a form most likely to get through and be understood.

For instance, if you need to communicate with a sensor who prefers seeing a step-by-step breakdown of a plan, and you are an intuitor who’d rather skip the details in favor of the big picture, you should emphasize each step of the plan. “Charles, I’d like to give you a breakdown of how this plan will be implemented and get your input,” is a good place to start. Or, “Laura, I’ve divided this proposal into three phases and want to see what you think.” Coworkers will respond positively to your efforts and will often reciprocate.

If you are a detail-oriented person who relies on numerical tables and charts, but need to communicate your findings to an intuitor, you can adjust by including a big-picture view of your proposal. You might say, “This proposal for a new accounting system will put us on the cutting edge, allowing us to keep better eye on the bottom line.” The anecdotal story approach also taps into the method intuitors use to make decisions. You can say something like, “Let me tell you how I see this idea affecting the typical person in our department.”

![]() Exercise 4–2. Other Preferences

Exercise 4–2. Other Preferences

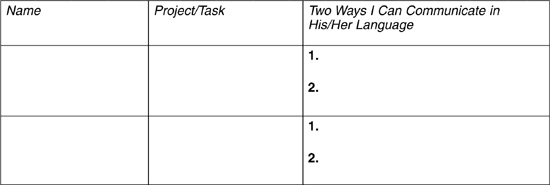

Jot down the names of two coworkers you deal with on a regular basis who have different communication preferences than yours. After their names, list a current project or task involving you and each coworker. For each situation, write down two ways that you can communicate your part in the task or project to them in their “language.”

Don’t be afraid to try a new way of communicating, even if there is a long history of miscommunication between you and a particular coworker. Just making the effort demonstrates your willingness to bridge the gap, and sometimes a coworker will meet you halfway.

Don’t Pigeonhole People

One final piece of advice: don’t pigeonhole or stereotype people based on what you see as personality type. It’s easy to say, “She’s an introvert, so we shouldn’t ask her to go out and generate contacts with potential customers.” This would be a mistake. Human personality is a complex subject and people are enormously flexible—much more flexible than the theories that psychologists have developed about human behavior. So don’t use Myers-Briggs or any other system to force people into narrowly defined workplace roles or to assume what they are capable of doing.

Different personality types have different communication preferences, and these naturally affect workplace communication, sometimes for the worst. People can reduce the negative impact of personality differences by recognizing and accommodating them.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® (MBTI) is a useful approach to understanding personality difference and is used widely in the business world. MBTI is built around four opposing pairs of personality types: extraversion/introversion; sensing/intuitive; thinking/feeling; judging/perceiving. The MBTI method measures where an individual falls along a continuum between each of these opposing pairs. None of the opposing types is better than any others; they are merely different. To communicative effectively with various personality types, we must recognize those differences and make adjustments in how we approach them. Knowing something about our own preference for giving and receiving information and about making decisions can help us when we communicate with our bosses, teammates, customers, and coworkers. And if you recognize the preferences of these other people, you’ll be able to adapt in ways that make your communications more effective.

Bridging the gap between personality types in communication requires finding common ground. This is accomplished through asking, collaborating, thanking, and speaking in the appropriate language.

1. Which of the following is an attribute of the Sensing type? |

1. (a) |

(a) Preference for facts |

|

(b) Comfort with decision-making |

|

(c) Reliance on hunches |

|

(d) Thinker of creative ideas |

|

2. One key factor in getting the best from personality differences is: |

2. (d) |

(a) training. |

|

(b) extraversion. |

|

(c) education. |

|

(d) adaptability. |

|

3. “Speaking the language” of a coworker with a different personality type involves: |

3. (b) |

(a) becoming just like the coworker you want to communicate with. |

|

(b) considering how to put information in terms the personality type of the coworker is most receptive to. |

|

(c) bringing along a third party to interpret if communication breaks down. |

|

(d) always writing down what you have to say before you say it. |

|

4. Which of the following is an attribute of the intuitive type? |

4. (b) |

(a) Prefers step-by-step procedures |

|

(b) Has a “big-picture” orientation |

|

(c) Practices data-based risk-taking |

|

(d) Likes a quiet place to plan |

|

5. Showing appreciation to other personality types in the workplace accomplishes two things. One of them is: |

5. (d) |

(a) increasing goodwill within the department or office. |

|

(b) making others believe you care what they think. |

|

(c) getting others to show appreciation back to you. |

|

(d) influencing others to “hear you out” in the future when you offer a perspective different from theirs. |

|

Think About It . . .

Think About It . . .