9

When You Aim to Persuade

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• Explain the necessity of persuasion in the workplace.

• List the three building blocks of persuasive communications.

• Identify four ways of building a persuasive case.

• Understand how choice of language can make you more persuasive.

AN ESSENTIAL WORKPLACE SKILL

Previous chapters of this course have explained how you can become a better communicator. They have identified barriers to effective communication, discussed the effect of personality difference on communication, and given you tools to be a better receiver and sender of information.

This chapter describes a communication skill that is important to everyone in the workplace—from the CEO’s office to the mailroom: persuasion. Persuasion is a communicative process through which we alter or affect the attitudes, beliefs, or actions of others. If you’re thinking, “What does that have to do with me? Persuasion is something that only sales people need to master,” then think again. Anyone who supervises others, or who must enlist the support of others in order to get things done, must understand and practice this important skill. Consider these examples of situations in which the ability to persuade is important:

A key customer has called to complain that the shipment she was promised two days ago hasn’t yet arrived. After a little checking you discover that someone has dropped the ball. The order was never shipped. Because satisfying this customer is so important, you pull all the stops. “Carmen, this is Ray. Someone screwed up and forgot to ship the Hoffmeister Company order, which is sitting in the loading dock area. We need to get it to the customer by tomorrow after noon. What can you do?” “Sorry, Ray,” says Carmen, “but I’m shorthanded today and won’t be able to get to it for a while.”

Susan is the leader of a cross-functional team charged with redesigning the company’s website. The team includes the financial controller, a marketing manager, and key people from each of the company’s four product groups. None of these people report to Susan, and most of them are more highly ranked than she. Each has his own agenda. Susan cannot tell any of them what to do, but she must somehow get them working together to produce a website that meets the company’s expectations.

Harold is on a mission. He has been working extremely hard for the past six months to do his own job and to cover for a coworker—an Army reservist who was called up for active duty. Harold has managed to keep everything working like clockwork, and the division has done well financially. Looking at his watch, he sees that it’s now time for the two o’clock meeting he had arranged with his boss. “I’m not coming out of that meeting without a significant raise,” he tells himself.

These three very different situations have one thing in common: a successful outcome will depend on someone’s ability to persuade. Ray must persuade Carmen to reorder her priorities and expedite the Hoffmeister shipment. Because Susan has no authority over the people on her team, she must use the power of persuasion to get them to work together toward a common goal. And finally, there’s Harold, who’s determined to get a raise from his boss. He too will have to be persuasive to get what he wants.

![]() Exercise 9–1. Your Experience with Persuasion

Exercise 9–1. Your Experience with Persuasion

Looking back over the past few weeks, identify three situations in which you or someone you work with (“persuaders”) used persuasive communication. Indicate the goal of that communication—that is, did the person attempt to alter or affect the attitudes, beliefs, or actions of others. Finally, note whether the persuader was successful.

If you keep your eyes open for it, you’ll see persuasion applied around you every day. It’s so commonplace that we often don’t think about it. Yet it is essential to getting things done. This chapter identifies the three building blocks of persuasive power, and then explains what you can do to increase the persuasiveness of your communications with others.

THE FOUNDATION OF PERSUASION

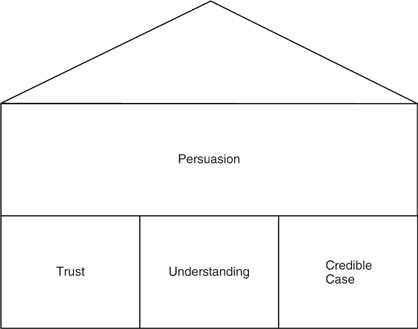

Like a building, effective persuasion rests on a solid foundation. That foundation is a combination of trust, understanding of the people one aims to persuade, and a credible case (Exhibit 9–1).

Trust

It’s difficult to persuade people who do not trust us. Would you purchase an item on an eBay auction if you didn’t trust that the condition of the product was truthfully described by the seller? Surely not. Would you be persuaded to accept someone’s sales forecast if you thought that person wasn’t knowledgeable about the subject, or used sloppy forecasting methods? Assuredly not. Anyone who aims to persuade in the absence of trust faces an uphill climb.

Here’s what we mean by trust. Trust is a condition wherein we have confidence in the character, ability, or truthfulness of someone else. We trust people when we believe that:

• They speak the truth.

• They respect or safeguard our interests.

• They know what they’re talking about.

• They are sincere in what they say to us.

• They have been reliable in the past.

• They do not disclose confidential information.

If asked, would your coworkers say that you have these trust-inspiring qualities? If they wouldn’t, work on them. Always keep on the right side of the truth in your dealings with others. Make a point of understanding the interests of others, and demonstrate respect for those interests. Never talk off the top of your head about serious business; instead, develop expertise in the subjects you deal with. Be sincere in your dealings—not a phony. Cultivate a reputation as a person others can count on—who does what she says. Finally, learn how to keep confidences. People are more inclined to trust a person who will not share sensitive information with others without the permission to do so.

Understanding

You’ll be more persuasive in your communications as you come to understand the people you’re trying to influence and gain a “big picture” view of the situation you are trying to change. The more successful you are at putting yourself into the shoes of the people you are trying to persuade, the more successful your persuasion will be. If you truly understand a situation from the viewpoints of others, you will adapt your proposal in ways that will benefit them, making your persuasion task easier.

It’s intuitively obvious that the more you know about someone, her interests, viewpoints, and needs, the more successful you’ll be in communicating persuasively. You’ll be prepared to package your message in a manner that has impact.

Every sales person understands the importance of understanding the audience. For example, a sharp real estate agent won’t just drive a new client around to look at for-sale houses. He’ll first ask questions:

“Are you currently living in a house or an apartment? If it’s a house, do you already have a buyer lined up?”

“How large of a house are you looking for—number of bedrooms, bathrooms, and so forth?”

“Do you have your eye on a particular part of town or neighborhood?”

“How large a monthly house payment—including taxes and insurance—are you willing to pay? And how much cash do you have available for a down payment?”

You get the idea. Understanding your audience before you try to persuade them is common sense. If, for example, you aim to persuade your boss and coworkers to adopt a new process for handling an essential routine, you might try to understand:

• How attached are individual coworkers to the current process?

• How would the change you propose affect them—both negatively and positively?

• Who, if anyone, would resist the change, and why?

• Who, if anyone, would strongly support the change—and perhaps become your ally?

If you think about the interests of the people you aim to persuade, you’ll be in a much better position to bring them around to your view.

Understand How Decisions Are Made

Understanding the people you aim to persuade includes understanding how decisions are made. This is important because persuasion often aims to influence a particular decision: a change in the work schedule or process, which new office technology should be purchased, how bonuses will be allocated, and so forth.

Typically, lower-level managers are allowed to decide on the small local issues, while bigger decisions are pushed up the chain of command to more senior managers, the executive team, the CEO, or even to the board of directors. In some departments, project- or work-teams can make decisions up to a certain level.

![]() Exercise 9–2. You and Your Boss

Exercise 9–2. You and Your Boss

Imagine that you want to persuade your boss to allow you to share a job with a coworker. List three concerns or objections that your boss might have to this arrangement. For each, indicate how you would respond to those concerns/objections in persuading your boss.

Identify the Key Decision Makers and Thought Leaders

Once you understand the process for making decisions, identify the key players and thought leaders. Thought leaders are the people whom others listen to when important matters are on the table. They may have organizational authority—a supervisor or manager—technical expertise, or just the kind of good sense that commands respect from others. Key players and thought leaders are the people on whom you’ll want to focus your persuasive communication. Just be careful, the person you assume to be the decision maker may be highly influenced by one or more people you wouldn’t expect. Consider this example:

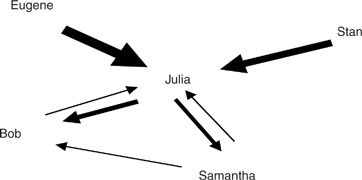

Julia manages the customer service department of a medium-sized direct mail retail enterprise. Bob and Samantha, her direct reports, supervise the other 15 people in the department and try to ensure that their work follows the game plan and is highly efficient. If you were advocating on behalf of a new telecommunications system to handle customer calls, you’d probably tell yourself, “Julia’s the key decision maker, but she’ll likely consult with Bob and Samantha on something like this.” And you would probably be right. But don’t accept the obvious; try to find out who else will influence the decision.

In this case, you might discover that Eugene, the head of tech support, will be a major influence. Stan, the chief financial officer, would be another likely influencer of the decision. Since Stan will be authorizing payment for the new system, he, and not Julia, may be the real decision maker in this situation.

![]() Exercise 9–3. Draw an Influence Map

Exercise 9–3. Draw an Influence Map

Who is influencing whom in your department on key issues? Think of one important decision your department is currently grappling with. Then, in the space provided below, develop an influence map like the one in Exhibit 9–2. Use bold arrows to indicate strong influence. This map is bound to be subjective, so ask a coworker to comment on it. That person may understand something you do not about the patterns of influence in the workplace environment.

If the decision process gets too confusing, try drawing an influence map, like the one shown in Exhibit 9–2. An influence map will help you sort things out. The arrows in the map indicate who is influencing whom in the decision to purchase a new telecom system. The bold arrows represent strong influence, as in Eugene’s influence over Julia; the thin arrows represent weaker influence. Notice, too, that influence is a two-way street in some cases. For instance, Julia influences Bob and Samantha, but to a greater extent than they influence her.

A Credible Case

The third foundation of successful persuasion is a credible case based on logic. People have trouble saying no to logical arguments.

One of the authors recalls how his then 17-year-old daughter came to him with a proposal to fly from Boston to San Francisco to see that city, visit friends, and also visit the nearby University of California, Santa Cruz, which was on her list of prospective colleges. Her father didn’t like the idea. A young girl traveling alone and hanging out with people he hadn’t met set off his parental alarm bells. “You won’t know your way around,” he complained. “You’ll have no where to stay. And it’s an expense that’s not in my budget this spring.”

This father had a mental list of why his daughter’s idea was not a good one. To his chagrin, however, she had prepared a solid and credible case in favor of the trip that addressed each of his concerns. She handed him an itinerary that included her proposed flight schedule, the names of friends who would pick her up at the airport and shuttle her around, the names and phone numbers of the friends’ parents with whom she would stay, the University admission personnel whom she planned to meet, and an estimate of the trip’s total cost. “I have almost half of it saved,” she told him, “so I’ll only need a few hundred dollars.”

By building a credible, logical case for her proposal, this teenager had countered each of the objections she knew that her father would bring up. So, in the end, Dad caved in. “How could I say no,” he told himself. “She had thought through the important issues and developed a plan I couldn’t disagree with.”

It’s easy for people to be dismissive of persuasive efforts when the would-be persuader hasn’t done his homework—that is, hasn’t developed a solid, fact-based case. This is especially true when a proposal requires people to change what they are doing or take a calculated risk. But as the previous story makes clear, fair-minded people find it difficult to say no to something that is logical and valuable.

Too many people fail to give proper attention to this third building block of persuasion. They have an idea that makes sense to them, but don’t take the time to see it from the perspective of the people whose approval and collaboration they need. Extraverts, those outgoing people we met back in Chapter 4, often have this problem. Since they process ideas through interactions with others, they are apt to spring their ideas before those ideas are fully developed. Those ideas are often shot down as a result.

Here are four tips for building a credible case:

1. Tip 1: Check your assumptions. Think through the things that will have to happen for your idea to succeed: a change in the work routine, an increase in the budget, training of personnel, and so forth. Be sure that your assumptions are reasonable and that your audience would agree that they are reasonable.

2. Tip 2: Think of feasible alternatives to your idea, as well their strengths and weaknesses. That way if someone says, “We should do it this way instead,” you’ll be prepared to point out the weaknesses of that alternative.

3. Tip 3: Develop a contingency plan. A contingency plan identifies actions that can be taken if your idea doesn’t work. For example, “We’ll keep the old telecom system online as a backup. That way, if the new system has bugs, we’ll still be able to communicate while we work them out.”

4. Tip 4: Obtain endorsements for your case. When people see endorsements or testimonials from people they know and respect, they are more likely to open their minds to your idea.

THE LANGUAGE OF PERSUASION

The three building blocks just described are necessary but insufficient for success in most cases of persuasion. They may get you close to the finish line but you need one more thing to carry you over—a persuasive delivery. You need persuasive language that addresses both the heads and emotions of your coworkers.

Emphasize the Benefits

Every salesperson knows the difference between features and benefits. When someone says “This computer has a 2.33 megahertz processor and a VereX bus,” that person is describing features. Features are necessary in that they set the ground work. You should communicate them. But benefits are what really persuade people.

• “Because this is such a fast computer, you won’t be sitting there waiting and waiting. And we all hate waiting….”

• If we adopt the new work process I’ve described (features), we will improve employee productivity by 20 percent. And that will save our department $180,000 in salaries and benefits every year.”

Notice the appealing benefits stated in both of those cases.

Speak to the Head and the Gut

In many instances you will be more persuasive if you appeal to both the mind and the emotions of your audience. Remember the Star Trek character, Mr. Spock? Because of his Vulcan genetic heritage, Spock was dismissive of any proposal or representation that was illogical, irrational, or based on emotions. He approached things almost entirely with his mind. The people you deal with at work, however, have both logical and emotional sides to their thinking and behavior. To be a successful persuader, you must judge how much to communicate to those two sides. People in finance, or accounting, or inventory control may respond best to a purely logical appeal, but others may not. The mistake that many make is to communicate the logic and forget the emotional appeal.

Every great public speaker understands the power of an emotional appeal. Consider Winston Churchill’s famous broadcast to the British people in the early days of World War II, when their army had been defeated at Dunkirk in France and the island nation stood alone against the more powerful forces of Nazi Germany. Churchill did not lay a bunch of dull statistics on his listeners. Instead, he spoke to their hearts, evoking the emotional courage they would need to carry on during the weeks and months ahead.

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail.

We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender. . .

In the business world the power of the emotional appeal is evidenced in the advertising that companies use to persuade people to buy. Check it out yourself the next time you view a TV or print ad.

So, in speaking to coworkers with the aim of persuading, address their emotions and aspirations:

The current work process has served us well for the past five years. But the pace of competition calls for something new and better. The new process I’ve described will take us to a higher level of performance. It will make our work faster, more error-free, and more satisfying to customers. And that improved performance will show up in our paychecks. And who can argue with that?

Be Positive and Affirmative in Communicating Your Ideas

Few things are as annoying as experts who qualify the case they’re trying to make with “I think that…,” “I think that we should be looking for a new strategy,” “I think that we should change our process,” or worse, “I think that what I meant in that report was. . . .”

If you’re trying to persuade someone to adopt your view, don’t say, “I think that . . .”. You might as well say, “I not sure, but . . . .” These qualifications tell listeners that you may be wrong, or that you lack confidence in your view, or that you’re offering nothing but a personal opinion. Instead, be affirmative; say:

“We should adopt a new strategy.”

“We must change our process.”

If you’ve built a credible case, you can make affirmative statements with confidence. And your confidence will inspire confidence in your listeners.

Also, minimize the use of “if.” “If we manage to change our process, productivity will improve.” This is another qualifier. Instead, be affirmative and say something like this: “When we change the process . . .” or “Once we’ve changed the process, productivity will improve.”

Cite Endorsements from Others

In many cases you can strengthen the persuasiveness of your communication by citing endorsements of your case, as in this example:

“If you have any reluctance about switching to the new version of this software, let me read you this email I received last week from Sarah Green in our Marketing Department:”

Bill: We switched to the 2.0 version of In Touch collaboration software a few months ago. It took several weeks for people to get comfortable with the new features, but it was worth the effort. The new version has improved our productivity by at least 25 percent.

If you use endorsements, just be sure that they are from people or organizations your listeners respect or have some authority in the matter.

Persuasion is an important workplace communication skill that everyone should master. The three building blocks of persuasion are trust, understanding, and a credible case. To build trust, always behave in a trustworthy way. Increase your understanding of the people you are trying to persuade; become aware of how decisions are made in your organization and identify the key decision makers for the decision you are trying to influence. Build a credible case by checking your assumptions, being aware of alternatives to your idea, developing a contingency plan, and obtaining endorsements from others. Finally, use the language of persuasion. Emphasize the benefits of your proposal; speak to both the intellect and the emotions; use positive, definite language; and cite endorsements from others.

1. A contingency plan: |

1. (b) |

(a) is the same as a credible case. |

|

(b) identifies actions to be taken if the original plan fails. |

|

(c) should not be communicated because it suggests that you don’t have faith in your plan. |

|

(d) gives people an opportunity to communicate about their goals. |

|

2. A communicative process through which we alter or affect the attitudes, beliefs, or actions of others is called: |

2. (d) |

(a) dialogue. |

|

(b) debate. |

|

(c) contingency planning. |

|

(d) persuasion. |

|

3. Trust is: |

3. (a) |

(a) a condition wherein we have confidence in the character, ability, or truthfulness of someone else. |

|

(b) a product of a person’s receptivity to particular ideas. |

|

(c) communication that harmonizes beliefs. |

|

(d) a key element in planning. |

|

4. Which of the following is one of the three building blocks of persuasion, as described in this chapter? |

4. (b) |

(a) The ability to speak and write well |

|

(b) Understanding the people you aim to persuade |

|

(c) Organizational authority |

|

(d) Control over resources |

|

5. When trying to persuade others, be sure to emphasize: |

5. (a) |

(a) the benefits of your proposal to listeners. |

|

(b) the features of your proposal to listeners. |

|

(c) your organizational authority. |

|

(d) your influence within the company. |

Review Questions

Review Questions