The Social Competence of Children Diagnosed With Specific Language Impairment

California State University, Fullerton

Anaheim City School District

Placetinia Yorba Linda Unified School District

Traditional approaches to the study of social competence of children have not considered the full range of factors involved in judging a child’s social competence. The approaches have typically designed abstract measures of children’s social competence and used the measures to classify the children as socially competent or socially incompetent. Some researchers, for example, have used teachers’ and children’s judgments of a student’s likability as a sole indicator of that child’s social competence (e.g., Black & Hazen, 1990; Denham & Holt, 1993; Masters & Furman, 1981; Terry & Coie, 1991). Other researchers, with the aim of assessing the social abilities of children with communication problems, have asked the children to perform tasks that require social knowledge, such as solving problems requiring social information (e.g., Stevens & Bliss, 1995; Tur-Kaspa & Bryan, 1994). These approaches to determining children’s social competence fail to consider the multidimensional and socially situated nature of social understanding and performance.

This chapter reviews and critiques research using abstract, dimensionalized views of social competence. Data are then presented from interactions among children with specific language impairments. Detailed analysis of a particular interaction is used to illustrate how social competence can be revealed in situated contexts and how a child’s competence might be judged differently depending on what is going on at the time.

TRADITIONAL APPROACHES TO STUDIES OF SOCIAL COMPETENCE

Much of the research on social competence has focused on social acceptance of children by teachers and other children. The studies have mostly been of nondisabled, middle class, European-American children. The degree of social acceptance by peers has been measured through nomination procedures and rating scales (e.g., Terry & Coie, 1991). The nomination-based method requires children to name or point to pictures of children they like best or like least. In a peer-rating method, children use a Likert-type rating scale to indicate how much they like or would like to play with each classmate. Researchers using these approaches compile the responses of a group of children, and use the results to determine which children are accepted, ignored, or disliked by their peers. Popular children are defined as those who receive more positive nominations or ratings and fewer negative nominations or ratings from peers.

Certain communication behaviors have been found to be consistently associated with popularity. Children who are perceived as more popular are more likely to alternate turns, produce explanations for playmates, and participate in extended discourse with a conversational partner (Black & Logan, 1995). Well-liked preschoolers have been found to demonstrate less aggressive and difficult behavior than peers (Denham & Holt, 1993).

Popular children have been deemed effective in dealing with problematic situations: boys adopt other boys’ frames of reference, make comments relevant to a group’s purpose, and exhibit greater accuracy in perceiving peers’ behavior (Black & Hazen, 1990). In contrast, unpopular children generate fewer effective solutions to problematic social situations (Stevens & Bliss, 1995; Richard & Dodge, 1982). They are also less effective in entering play groups than their popular counterparts, providing significantly more informational questions (“What is that for?”), and disagreements, during entry attempts.

In addition to nomination and rating scales, experimental approaches have been used to evaluate children’s social competence. Experimental studies designed to measure children’s social knowledge have indicated, for example, that children with learning or language problems had trouble performing tasks designed to measure social competence. Tur-Kaspa and Bryan (1994) found that children with learning disabilities had more difficulties with some aspects of a social information processing task than average and low-achieving peers, particularly in attending to environmental cues and storing social information. Stevens and Bliss (1995) discovered that children with severe language impairments offer fewer and less cooperative strategies when proposing hypothetical solutions to peer conflicts.

The above studies of children’s social competence have assumed that children who are not accepted socially by their peers or those who perform below average on tasks measuring social competence are lacking in social competence. These traditional approaches to studying social competence in normal children have also been used to study the social competence of children with language/learning difficulties. For example, Haager and Vaughn (1995) and Merrell (1991) found that teachers rated children with learning disabilities as less socially competent than their typical peers; and Fujiki, Brinton, and Todd (1996) obtained similar results when studying children with specific language impairment (SLI). Peer ratings have also revealed that children with learning disabilities, SLI, or low achievement are less popular than their schoolmates (Gertner, Rice, & Hadley, 1994; Haager & Vaughn, 1995; Priel & Leshem, 1990).

There are two approaches that offer a departure from traditional ways of studying children’s social competence. The first is to treat a particular type of behavior as a cultural construct and study how commonly occurring behaviors are interpreted by members of different groups. Using this interpretive approach, researchers have compared interpretations of social behaviors made by children from different cultural groups and with different temperaments. For example, comparisons have been made of how aggressive and unaggressive male adolescents interpret hostility in their peers. Unaggressive males from both European-American and African-American communities were found to be less likely to attribute hostile intentions to peers than their more aggressive classmates (Hudley & Graham, 1993; Graham & Hudley, 1994). Other studies have interpreted how children interpret verbal assertiveness and witty verbal play in others. Low-income children from both African-American and European-American backgrounds were found to value such behavior (Miller & Sperry, 1987; Mitchell-Kernan & Kernan, 1977). Lastly, Canadian and Chinese children were found to differ in their interpretations of shyness and sensitivity in others. The traits of shyness and sensitivity were negatively correlated with peer acceptance among Canadian children, but were positively related to peer acceptance by Chinese children (Chen, Rubin, & Sun, 1992).

These cross-cultural comparisons imply that a child who is judged to have social problems as the result of acting in a particular manner in one context, may be seen as socially adept in another, based on the same behaviors. The evaluation would depend on the framework within which the child’s behaviors are evaluated.

Another departure from the nomination, rating, and experimental approaches to studying children’s social competence is one in which specific social interactions of children are studied in detail. Researchers, for example, have compared the way children with language/learning problems and typical children negotiate entry into play groups. Using such an approach, Craig and Washington (1993) found that young typical children gained entry into play groups within 20 minutes by approaching the groups, producing an action to advance group play, and describing the action as they performed it. Two of the five children with SLI in the study gained entry. These two children performed actions that advanced the group’s play, but did so without speaking. The other three children with SLI, who did not perform actions advancing play, failed to gain access to play groups. These findings reveal the complexity of social interaction as it is enacted during a specific activity. Of particular relevance in the Craig and Washington study is that the language deficit may or may not impact on a child’s success in entering play. The child’s successful entry into group play in these cases depended on whether the child used nonverbal behaviors compatible with the ongoing play activity.

In summary, the literature on children’s social interaction has tended to dichotomize children into those who are socially competent or popular, using teacher or peer evaluation approaches or designing tasks as quantitative measures of children’s social competence. Children who are diagnosed as having language or learning problems are more likely than their typical classmates to be classified by their teachers or peers as socially incompetent. These dichotomous characterizations and single-dimension measures of social competence have not considered what may be contributing to the ratings of children, and have failed to appreciate the complexity and contextually based nature of communicative interaction. They have treated social behaviors as value free and amenable to standardized measuring instruments.

The following study, like that of Craig and Washington (1993), examined children’s interactions as they unfolded. The children in the interactions have been diagnosed as having specific language impairment. Data reveal that teachers’ judgments of who is more socially competent on a particular occasion depend on the frame of reference used to interpret the children’s behavior. Furthermore, data suggest that traditional measures of social competence are insufficient to account for the complexity of the social negotiations that take place in everyday interactions. The children in this study, whether rated as competent or incompetent by their teachers, demonstrated highly sophisticated interactional competencies as they went about achieving their social goals.

SOCIAL COMPETENCE OF CHILDREN WITH SLI AS DISPLAYED IN THEIR EVERYDAY PLAY

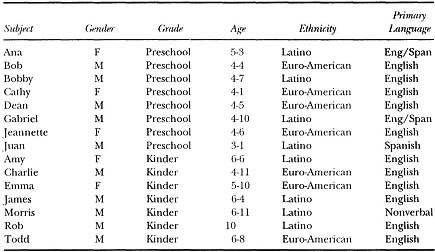

This study involves detailed analysis of interactions between preschool children, all of whom have been diagnosed as having specific language impairment. The data to be presented were part of a larger study of two classrooms of children, a kindergarten and a preschool (see Saenz, 1992, for details about the larger study). The children in the larger study were from two classes for the communicatively handicapped in a school in the metropolitan Los Angeles area (see Table 5.1). All of the children but two, Cathy and Charles, had been placed in these classrooms because of a diagnosed language disorder, and the majority had other medical or learning problems (see Table 5.2). One class included 8 preschoolers ranging in age from 3 years, 1 month to 5 years, 3 months; the other class was made up of 7 kindergartners aged 4 years, 11 months to 6 years, 11 months. One of the children in the preschool class was female and there were two female children in the kindergarten class. The preschool class was comprised of four Mexican-American children and four European-American children, and the kindergarten class included four Mexican-American children and three European-American children. All bilingual students demonstrated limited English proficiency, as well as limited proficiency in their primary language of Spanish. In addition, an older child with language and medical problems from another classroom occasionally joined the younger children in play.

Procedures

Students were observed during 19 free-play sessions of 25 minutes each from January to June of 1994. For the first 15 minutes, the two classes played together, then the older class left. Thirty sessions of free play were videotaped, totaling 749 minutes. The videotaped data reported on here focus on the preschoolers and their efforts to obtain objects from other children. Instances in which the words and actions of the participants were not clearly audible or visible were omitted from analysis.

TABLE 5.1

Preschool Subjects and Kindergarten Playmates

TABLE 5.2

Preschool Subjects and Medican and Other Disabilities

| Subject | Birthdate | Disabilities |

| Preschool Class | ||

| Ana | 1-11-89 | Language disorder, visual and motor problems |

| Bob | 12-14-89 | Prader-Willi syndrome, self-help, motor problems |

| Bobby | 9-3-89 | Language and motor problems |

| Cathy | 3-30-89 | Other health impaired with visual problems, shunt |

| Dean | 11-18-89 | Language disorder |

| Gabriel | 6-1-89 | Language disorder, other health impaired, kidney failure |

| Jeannette | 10-6-89 | Language disorder, seizures |

| Juan | 3-19-91 | Language disorder, other health impaired, seizures |

| Kindergarten Class | ||

| Amy | 10-1-87 | Language disorder |

| Charlie | 5-1-89 | Other health impaired, visual impairment, suspected prenatal drug exposure |

| Emma | 5-28-88 | Language disorder |

| James | 12-12-87 | Language disorder, visual impairment, prenatal drug exposure |

| Morris | 5-7-87 | Language disorder, autism |

| Rob | 6-11-88 | Language disorder |

| Todd | 8-31-87 | Language disorder |

All instances involving efforts to obtain objects were transcribed orthographically by the first author. For reliability, a research assistant independently transcribed 23 segments, each 1 minute long, of the videotaped interactions. Comparisons of the same segments between both transcribers revealed 82.9% coder agreement for the transcription of words and nonverbal actions.

The second and third authors were trained by the first author to identify incidents in which one child tried to obtain an object from another and to code incidents by requesters’ strategies, requestees’ initial responses, and requesters’ success in obtaining objects. To be described as an object attainment incident, the requestee had to be touching the object at the time the requester attempted to touch it or take it away.

Success in obtaining an object was defined from the requester’s point of view and occurred whenever the requester was able to physically touch an object and play with it. In most cases, the requester gained exclusive possession of the object, but in some instances the requestee continued to play with the object as well.

The second and third authors independently reviewed transcripts of the videotaped free-play sessions and identified all incidents in which a preschooler attempted to obtain an object from a peer. The percentage of agreement between the two authors was 75%. The two authors then met and resolved all discrepancies.

Five strategies for obtaining objects were selected for coding. They were adapted from Saenz’s (1992) study of typical preschoolers’ strategies for obtaining objects from peers. The strategies were:

1. Movement toward an object

2. Verbal intentions with movement toward an object

3. Verbal intentions

4. Claiming with movement toward an object

5. Claiming

The strategy of movement toward an object was defined as any physical attempt to obtain an object held by another child, including reaching, touching, or grasping. Verbal intentions included verbal requests, demands, or statements used to obtain an object held by another child, such as “gimme.” Claiming was an assertion of the right to obtain an object from another child, and involved such utterances as “mine” and “it’s mine.” The percentage of agreement between the second and third authors for coding these strategies was 86%.

Results

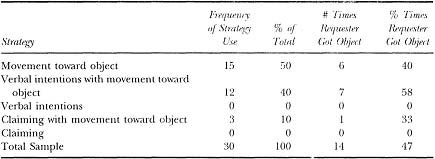

Three of the five strategies were displayed by children in this study: movement toward an object, verbal intentions with movement toward an object, and claiming with movement toward an object. As Table 5.3 illustrates, movement toward an object constituted 15 (50%) of the 30 incidents and was successful on 6 (40%) of those 15 occasions. Verbal intentions with movement toward an object occurred in 12 (40%) of the instances and was successful 7 times (58%) when attempted. Claiming with movement toward an object occurred three times (10%) and was successful only once.

The frequency of occurrences and their relative success provide one index of social competence. However, these data, like that in the experimental studies, do not describe how these successful and unsuccessful attempts were carried out. For this purpose, an interaction of two of the children, Gabriel and Bobby, will be analyzed as it unfolded.

Gabriel was a sociable Latino child with limited verbal communication skills in Spanish and English. He was soft-spoken and often relied on gestures and actions, as opposed to words, to communicate. Gabriel consistently demonstrated close attention to the actions and words of other children and adults, turning these observations to his advantage during his efforts to secure objects from peers. He joined students in the class and they played together with their toys, or he allowed other children to join him in his play. His two most frequent playmates, Ana and Juan, did not display resistance to his incursions into their play space and often shared their toys cooperatively with Gabriel. Although he said far less than Bobby, he was judged by classroom teachers to exhibit more appropriate social skills in the classroom. Gabriel’s high level of nonverbal communication was perceived by his teachers to compensate for his lack of verbal skills. In addition, he was often successful in obtaining objects from peers or resolving conflicts with peers. In sum, Gabriel was not only well liked by his teachers, he was regarded by them as more interactionally competent.

TABLE 5.3

Effectiveness of Strategies Used to Obtain Objects

Bobby, also Latino, differed from Gabriel in that he was often unwilling to share toys. On one occasion, Bobby picked up a Fisher-Price clubhouse to remove it from other children who were also playing with it. Unlike other children in the class, Bobby frequently protested to teachers when other children’s behavior did not meet with his approval. As a result, teachers often observed a play group more closely after Bobby entered it, in the expectation that conflict might occur.

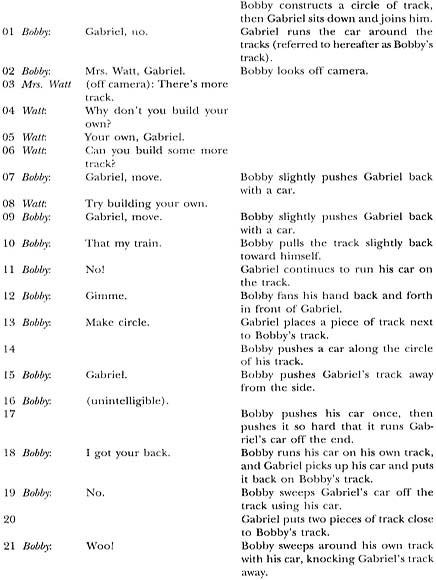

The transcribed excerpt reveals that although Gabriel is viewed as a more sociable child than Bobby in terms of his ability to interact with others, his means for obtaining objects did not necessarily display a concern for negative reaction from his peers, particularly Bobby. In this segment, Gabriel succeeded in playing with Bobby’s train track in spite of Bobby’s attempts to make him leave. During their disagreement over the train track, Bobby communicated his distress through speech and gesture while Gabriel responded nonverbally.

TRANSCRIPTION (APRIL 26, 1996)

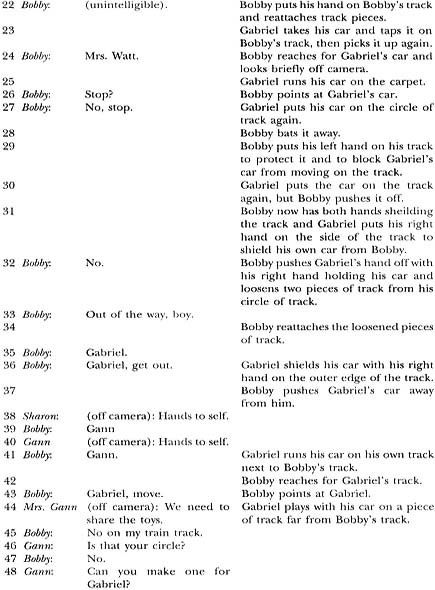

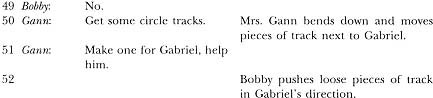

Gabriel’s nonverbal persistence in obtaining toys eventually overcame Bobby’s verbal and nonverbal protests. Even though Mrs. Watt instructed Gabriel to build his own railroad track (turns 4–6), he proceeded to build a track immediately adjoining Bobby’s, potentially interfering with Bobby’s solitary play. Then Bobby tried to block Gabriel’s action with his hand (12). Undaunted by this action, Gabriel laid down an adjacent piece of track (13). Bobby responded by moving Gabriel’s track away (15), and later by pushing Gabriel’s track apart (21). From 22 through 48, Gabriel continued to place his own car on Bobby’s tracks while Bobby attempted to push or sweep the car off. Finally, in 49–52, Mrs. Gann, another teacher, urged Bobby to help Gabriel make a circle for himself. Bobby relented and pushed some of the train track in Gabriel’s direction (53).

In order to interpret and evaluate the online social competence of Bobby and Gabriel as it took place in this interaction, one must assume a particular point of view. Two views that can be applied to Bobby and Gabriel are often framed as explicit or implicit social rules for children to follow: (a) children should share their toys, and (b) if someone is already playing with a toy, that child should have first rights to that toy. Mrs. Gann, in line 45, explicitly tries to resolve the conflict between Bobby and Gabriel in light of the first rule by saying “we need to share the toys.” This view, when used to evaluate the interaction, would place Bobby at fault for not sharing his track with Gabriel. Bobby is thus cast as the one who is creating the social problem.

Mrs. Watt, interestingly, responds to the same interaction (but earlier) in accord with the second view. She tells Gabriel early on in the interaction that there is plenty of track to go around. This implies that Gabriel is the one causing the problem, encroaching on Bobby’s territory. Bobby, when appealing to each of his teachers, might be doing so in anticipation that the teachers will intervene on his behalf. That is, they would stop Gabriel’s intrusions. If his appeal were, indeed, acted on by a teacher, it would be under the aegis of the territorial rights rule, not the sharing rule.

Both children display complex social competencies when making their goals explicit to one another. Bobby was clear, both verbally and nonverbally, in expressing his desire to retain sole control over the toys. In defending his play territory, he showed social versatility in telling Gabriel to move (7), by suggesting that Gabriel build his own track (13), and by making a variety of different physical and verbal attempts to block Gabriel’s intrusions (e.g., 19, 21, 26, 33, 34).

Gabriel communicated his intents and negotiated with Bobby nonverbally. He alternated direct intrusions on Bobby’s track with lesser intrusions, as if to test the territoriality rule held by Bobby. His most direct intrusions were to put his car on Bobby’s already formed track and, if it remained there, to run it around Bobby’s track. He did this several times (1, 11, 18, 27, 30). When Bobby reacted, Gabriel retreated from this direct approach to assume a less confrontational one. He began making and running his cars on his own track next to Bobby’s track (13, 20), then retreated to a weaker position of running his car on the carpet (25), and later to building a new track (45).

When viewed from the framework of “children should share,” the conflict is seen as originating with Bobby’s reluctance to share his toys with Gabriel. When viewed as an instance of children’s need to assert their territorial rights, Gabriel becomes the culprit and problem person, lacking in social knowledge or skills.

CONCLUSION

This detailed analysis of a single interaction is presented to illustrate how an individual’s judged social competency can depend on what goes on in highly complex social interactions and how they are interpreted by participants and onlookers. Assessment approaches designed to determine whether or not individual children or a group of children are socially competent fail to capture the nature of the everyday experiences that lead teachers and children to their nomination and rating decisions. Assessment approaches that employ tasks for measuring children’s social knowledge, such as problems-solving tasks involving social situations, also fail to provide insights into how children are able to use their social knowledge to achieve their personal goals.

The analysis of the single excerpt between preschoolers Gabriel and Bobby, both diagnosed as having specific language impairment, revealed significant skills from both as they worked to achieve their desired goals. Perhaps one of the most striking features of the excerpt was Gabriel’s ability to obtain objects that were in the possession of other children, irrespective of their reactions and without verbal language. Gabriel was more favored socially by his teachers than Bobby, and yet from a certain vantage point it is hard to claim that his actions were more socially acceptable. He was confiscating toys from his peer in spite of the peer’s protest.

The excerpt also reveals that Bobby employed verbal as well as nonverbal means to achieve his goal. Bobby was quite clear in communicating his protests to both Gabriel and the teachers. Bobby’s verbal efforts to solicit help from the teachers, coupled with his verbal and nonverbal attempts to fend off Gabriel’s actions, were quite consistent with other data on how typically developing children in a mainstream day-care center sought to resolve their conflicts over objects (Kovarsky, 1993).

Judgments of Bobby’s social competence by his teachers seemed to be closely tied to his lack of willingness to cooperate with his peers. His frequent protestations of other children’s actions and reluctance to share toys with peers seemed to be the basis on which his teachers judged him as having social difficulties.

These data would suggest that incompetence is not the sole possession of the individual and that children should not be evaluated as having “social problems” that are intrinsic to their nature. Rather, portraits of competence and incompetence should be regarded as complex constructions, which can differ with the situation and are likely to be based on values and interpretations of those making the competency judgments, and not just on the performance or abilities of those who are being evaluated.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This chapter was completed with the support of an Affirmative Action grant from California State University, Fullerton. Data were adapted from the graduate project completed by Kelly Gilligan Black and Laura Pellegrini as a requirement for their masters’ degrees.

REFERENCES

Black, B., & Hazen, N. (1990). Social status and patterns of communication in acquainted and unacquainted preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 26, 379–387.

Black, B., & Logan, A. (1995). Links between communication patterns in mother-child, father-child, and child-peer interactions and children’s social status. Child Development, 66, 255–271.

Denham, S., & Holt, R. (1993). Preschoolers’ likability as cause or consequence of their social behavior. Developmental Psychology, 29, 271–275.

Fujiki, M., Brinton, B., & Todd, C. (1996). Social skills of children with specific language impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 27, 195–202.

Gertner, B., Rice, M., & Hadley, P. (1994). Influence of communicative competence on peer preferences in a preschool classroom. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37, 913–923.

Graham, S., & Hudley, C. (1994). Attributions of aggressive and nonaggressive African-American male adolescents: A study of construct accessibility. Developmental Psychology, 20, 365–373.

Haager, D., & Vaughn, S. (1995). Parent, teacher, peer and self-reports of the social competence of students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 28, 205–215, 231.

Hudley, C., & Graham, S. (1993). An attributional intervention to reduce peer-directed aggression among African-American boys. Child Development, 64, 124–138.

Kovarsky, D. (1993). Understanding language variation: Conflict talk in two day cares. ASHA Monographs, 30, 32–40.

Merrell, K. (1991). Teacher ratings of social competence and behavioral adjustment: Differences between learning-disabled, low-achieving, and typical students. Journal of School Psychology, 29, 207–217.

Miller, P., & Sperry, L. (1987). The socialization of anger and aggression. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 1–31.

Mitchell-Kernan, C., & Kernan, K. (1977). Pragmatics of directive choice among children. In S. Ervin-Tripp & C. Mitchell-Kernan (Eds.). Child discourse (pp. 189–208). New York: Academic Press.

Priel, B., & Leshem, T. (1990). Self-perceptions of first-and second-grade children with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23, 637–642.

Richard, B., & Dodge, K. (1982). Social maladjustment and problem solving in school-aged children. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 50, 226–233.

Saenz, T. I. (1992). Strategies for obtaining toys at Head Start. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA.

Stevens, L., & Bliss, L. (1995). Conflict resolution abilities of children with normal language. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 38, 599–611.

Swisher, L., & Plante, E. (1993). Nonverbal IQ tests reflect different relations among skills for specifically language-impaired and normal children: Brief report. Journal of Communication Disorders, 26, 65–71.

Swisher, L., Plante, E., & Lowell, S. (1994). Nonlinguistic deficits of children with language disorders complicate the interpretation of their nonverbal IQ scores. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 25, 235–240.

Tantam, D., Holmes, D., & Cordess, C. (1993). Nonverbal expression in autism of Asperger type. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 23, 111–133.

Terry, R. & Coie, J. (1991). A comparison of methods for defining sociometric status among children. Developmental Psychology, 27, 867–880.

Tur-Kaspa, H., & Bryan, T. (1994). Social information-processing skills of students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 9, 12–23.