Reports Written by Speech-Language Pathologists: The Role of Agenda in Constructing Client Competence

State University of New York at Buffalo

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) use a variety of discourse genres for their various activities. They engage in different types of oral discourse depending on who they are talking to and what they need to accomplish. When obtaining referrals, for example, they may converse with their professional peers about a client’s communication; when obtaining background history, they conduct interviews with their client or members of that person’s family; and when engaging in assessment and therapy activities they are likely to follow a preestablished oral script dictated by the test protocol or by an activity plan.

There are also behind-the-scenes discourses that involve SLPs in what they sometimes disparagingly refer to as “paperwork.” These are written reports or notes designed to document assessment findings, to lay out therapy goals, to aid in recalling aspects of client performance during therapy, and to report on progress a client makes resulting from a treatment regimen. Clinicians use different descriptive terms to label these various reports. Their descriptions, in many cases, coincide with what they hope to accomplish by the report. In evaluation reports, for example, they aim to report what they did when evaluating a client’s communication, what they found out, and what to do about their findings. They use progress reports somewhat differently from evaluation reports. Progress reports are designed to convey what was done during an intervention program and what progress a client made as a result of the program. Table 10.1 outlines several types of reports written by SLPs and the different purposes of these reports.

TABLE 10.1

Types of Reports Written by Speech-Language Pathologists

| Type of Report | Purpose of the Report |

| Evaluation reports | To report evaluation procedures and results and to suggest a course of action for remedying a problem if a problem was found |

| Progress notes | To make note of particular information from a particular session |

| Individualized educational plans Individualized family service plans Individualized habilitation plans |

To document short- and long-term intervention plans agreed upon by professionals, family members, and clients |

| Progress reports Discharge summaries Annual reports |

To report on progress made during intervention and suggest remedies for any remaining problems |

The few authors and researchers who have discussed different types of clinical report writing have described their formats (outlines) and commented on the purposes or agendas fulfilled by the different report types. (For a recent example, see Middleton, Pannbacker, Vekovius, Sanders, & Puett, 1992.) However, there has been no direct discussion in the clinical literature of how the discourse formats are related to the reports’ purposes and how those purposes may be affecting the ways the clients are portrayed (Haynes, Pindzola, & Emerick, 1992; Hegde, 1994; Meitus, 1983; Middleton et al., 1992; Neidecker, 1987; Sanders, 1972).

One possible way to examine how agendas impact on report writing is to compare the formats and wording of two types of reports that are designed to accomplish different agendas. Evaluation and progress reports provide an interesting contrast in this respect. Evaluation reports describe the existence (or absence) of a communication problem and offer a remedy. Progress reports, on the other hand, presuppose the existence of a communication problem and describe, instead, the progress a client has made as the result of a therapy regimen (Neidecker, 1987, p. 154). In order for evaluation reports to successfully argue for services to remedy a problem, they must contain an argument for client incompetence. Progress reports, on the other hand, if they are to achieve their purpose, must contain an argument that clients are improving.

Prescriptive formats for evaluation and progress reports have focused on a listing of major headings that correspond to the major discourse subsections of the report. Examples of subsections listed for evaluation reports are ones containing: identifying information, background information, assessment procedures, results, summary of findings, and recommendations (Emerick & Haynes, 1986; Lund & Duchan, 1993; Middleton et al., 1992; Sanders, 1972). Progress reports have been described as containing subsections similar to those in evaluation reports, such as identifying information and background information, and as having an additional section entitled progress, not present in the evaluation report. Authors describing formats for evaluation and progress reports have not discussed the logical relations between the subsections nor have they described the way the information is organized within each of the sections. Finally, there have been no studies of how such prescriptive formats compare with those used in actual reports written by practicing speech-language pathologists.

To investigate the influence of agendas on client portrayal and to fill some of the gaps in the literature, a discourse analysis was done of evaluation and progress reports written by practicing speech-language pathologists. The two types of reports were compared for how they formatted the information and how they described the clients. These reports were also compared with those described in the literature and with a report of a personal futures plan.

The personal futures plan is a report that has recently been developed by a small group of professionals and advocates of those with disabilities. The aim of a personal futures plan is to describe a set of procedures designed to support a person with disabilities to achieve future goals (Beukelman & Mirenda, 1992; Mount & Zwernik, 1988). Such plans contain a listing of goals and a set of procedures for achieving them. The emphasis of a personal futures plan is not to recommend ways of remediating a focus person’s disability, but to change situational demands so that the focus person and close affiliates (“circle of friends”) can achieve their “wishes” and avoid their “fears.” Personal futures plans are not readily available as reports, because they are not usually official documents that are placed in the focus person’s folder. Rather, they may be located on poster paper on a wall, to be referred to by those engaged in the planning process. There is an emerging literature describing personal futures plans, and one article contains a description of a particular plan (Vandercook & York, 1990). The description reveals the potential for a report that is designed to achieve an agenda quite different from that of traditional evaluation and progress reports. The discourse of that personal futures plan is therefore compared in this chapter with the discourse used in traditional evaluation and progress reports to further illuminate how overall agendas are closely related to how individuals in the reports are depicted.

METHOD

This study analyzes 10 evaluation reports, 10 progress reports, and a description of a personal futures plan. The evaluation and progress reports were written by different speech-language pathologists working in different professional settings (public schools, universities, hospitals). The personal futures plan was designed by a team of professionals and friends of a person with disabilities, the focus person. (The focus person also plays a large role in determining what is in the plan.)

The first analysis was of the global organization of evaluation and progress reports. Major sections of the reports were identified and their logical relations examined. The underlying logic was evaluated for how it was associated with the writers’ agendas and for how it portrayed the competence of those being written about. The report sections were also compared with those located in the literature descriptions of report formats.

A second analysis was done to discover how evaluation and progress reports describe their clients and whether those descriptions reflect differing agendas between the two report types. This analysis identified statements that described the subject, and classified them as positive or negative. The prediction was that evaluation reports would contain a predominance of negative descriptions in an effort to create an argument that the individual being written about had a communication problem. In contrast, it was predicted that progress reports would be more positive so that they could best make an argument for subject improvement.

A third analysis was of the information provided in a description of a personal futures plan, a report with a very different agenda from that of evaluation and progress reports. The global structure and descriptive statements in the plan were compared with those used in standard evaluation and progress reports.

RESULTS

Organization of Evaluation Reports

The evaluation reports in this study coincided broadly with the formats laid out in professional manuals and textbooks (Emerick & Haynes, 1986; Lund & Duchan, 1993; Middleton et al., 1992; Sanders, 1972). They were organized into major subsections, usually identifiable through the use of headings that separated sections from one another. Typical headings were: identifying information, statement of the problem (reason for referral or complaint), background information (case history), assessment procedures (tests administered), results, summary (conclusions), and recommendations.

Identifying Information and Statement of the Problem. The first section of evaluation reports provided readers with what has been termed “identifying information.” It included the child’s name, age, birthdate, grade, address, parents’ names and occupations, and phone number. Most reports included the current date (date of evaluation), name of the agency or school where the evaluation took place, the names of the referral source and of the clinician doing the evaluation. For many reports, this information was presented in a standardized listing at the top of the first page.

Evaluation reports’ first paragraphs sometimes contained restatements of some of the identifying information (name, age, clinic name). These beginnings provided information about who referred the child for the evaluation and the source of concern. This information was sometimes labeled by a heading such as “complaint” or “statement of the problem.” The parenthetical information following excerpts below indicates the work site—public school (PS), university (UNIV), hospital (HOSP)—the identification number of the report from which the excerpt was drawn, and whether the report was an evaluation (eval) or progress (progress) report. The names and places are changed to preserve anonymity.

Freddie Amber, a 5-year, 6-month-old kindergarten student, was referred for a speech and language evaluation by the Child Study Team of McClain Elementary School. Concerns had been expressed by Fred’s teacher, Ms. Gretta Denmore, regarding his classroom performance and distractibility. (PS, eval, 6)

Thus, the first section identified a theme—that the individual being reported about was someone who might have a problem. The focus of the rest of the report was on identifying the problem, and determining possible causes and remedies. This was the design of all the evaluation reports, even the ones in which no problem was found.

Background Information or Case History. The evaluation reports from hospitals and universities contained a case history section in which background information was presented about notable medical, social, educational, or developmental events. Most school reports did not have this section, perhaps because the referrals were from teachers who were not as likely to know the child’s early history. Case history descriptions were made within the framework of causality, inviting the reader to infer what had gone wrong in the past or what was problematic about other domains of development that might be contributing to the child’s current difficulties.

Mrs. Burkhart discussed the fact that both she and her husband have articulation problems due to congenital deficits. She has micrognathia and her husband has a cleft palate. Both parents are intelligible. No other familial speech-related deficits are reported. (UNIV, eval, 2)

As indicated by their organization and focus, case histories emphasized the clients’ problems more than their competencies. The histories were organized to provide significant background information that might reveal the time a problem may have originated, what might have caused it, and what other problems might be associated with it. Reports in which the children were found to have no problem also emphasized unusual aspects of medical, social, or physical history that could have produced a communication problem. The following excerpt was taken from a case history of a 4½-year-old child who was found to perform normally on all language measures:

According to Mrs. Frankel, Carol did not sit without support until she was 1 year old. Reportedly, Carol never crawled and was over 2 years old when she began to take her first steps. No problems with sucking, swallowing or chewing were reported. Mrs. Frankel stated that Carol was a noisy baby, but that she did not say her first recognizable word until age 2 years. (UNIV, eval, 3)

Assessment Procedures (Tests Administered), Results, and Summary. Once the client was introduced in the report and the historical information of a possible problem was provided, the reports moved to a description of what was done during the assessment. This description was often combined with a results section, indicating how clients performed on the assessment tasks. The descriptions were of performance on tasks that were difficult for them. The clinicians thus followed what Hegde (1994) has called “disorder specific assessment” (p. 165).

The presentation of details in the descriptions varied, with some reports presenting a listing of scores and others presenting a list of domains in which the client’s performance was found deficient. Scores were usually located in the results section. Lists often occurred in a section called “summary” that was organized something like the following:

Formal observations support language delay. Deficits include spatial concepts, inferential reasoning, instruction sequencing, lexical development, syntactic errors, and story formulation. Patient was not able to structurally organize language to explain events or make stories. (HOSP, eval, 7)

Often clients were reintroduced in the summary section, along with the list of problem areas. There was sometimes a brief mention of areas of competence.

Juan Escobar demonstrated a pattern of articulation and syntax typical of a speaker of English as a second language. Tests of auditory comprehension revealed moderately low understanding of vocabulary and grammatical elements. Pragmatics were most problematic for Juan. Deficits in topic maintenance and inappropriate responses to questions were noted. Voice and fluency were within normal limits. (UNIV, eval, 9)

Recommendations. The concluding section of most evaluation reports outlined ways to remedy the various problems presented in the results section. Most reports recommended individual intervention by a speech-language pathologist. Recommendations were also made for gathering additional information or evaluating a client in other areas to determine etiology or additional deficit areas. In the case of Juan in the example previously quoted, there were four recommendations:

Juan should be enrolled in a program of speech and language management twice a week for a one-hour session; therapy should emphasize auditory comprehension and the pragmatic communicative skills necessary to support academic and social achievement; information about Juan’s performance in a school setting should be acquired; hearing should be evaluated. (UNIV, eval, 9)

Organization of Progress Reports

Progress reports, as a group, were less homogeneous in their organizational structure than evaluation reports. For example, there were many instances of titled subsections that occurred only a few times: short- and long-term goals, methods, related information, and prognosis (estimated duration of treatment).

Although varying considerably from one another, progress reports were recognizable as such because of certain notable commonalities. All progress reports contained a heading with identifying information, a section on therapy methods, another section on therapy progress (sometimes these methods and progress sections were combined), and a final section on further recommendations.

Identifying Information. The section of the report headed “identifying information” contained demographic and clinical information about the client. This section was often identical with that of evaluation reports, with the possible additions of a specification of the number of times the person was seen in therapy, the period of time the therapy lasted, and the diagnostic classification of the client. This information was sometimes formatted as a list.

Background Information or History. Following the listing of identifying information, there was typically a short paragraph or two labeled “background information” or “history.” This section differed from the one in evaluation reports in that it described the location and type of therapy, as well as the problem areas targeted for intervention. The background information sections of progress reports varied considerably in length and detail. Some resembled evaluation reports, describing in detail the client’s medical or developmental history. Others provided only brief descriptions of the referral source and the focus of the intervention, and omitted other history related to the cause and course of the communication problem.

Arlo Grantham has been seen for 3 X 40 (120) minutes per week speech/language services since September 14, 1994 at Murray Hill School. Services were recommended as a result of a diagnostic evaluation by Ms. Elaine Rubin completed in April, 1994. (PS, progress, 1)

Progress (Present Status). The largest section of the progress reports described the individual’s change in performance over an identified therapy period. It was typically entitled “progress” or “present status.” This section contained several types of information. One was a description of the goals of the intervention. A second was a description of therapy approaches used in the course of intervention. These two information types were often merged in one sentence or in the same paragraph.

Language therapy has focused on reinforcing sound and symbol association in order to improve Arlo’s ability to sound out words, increasing receptive and expressive vocabulary, and improving pragmatic skills. Pragmatic skills addressed included conversational skills and team work with a peer. Helping Arlo to recognize his strengths and take an active role in his learning as well as reinforcing classroom spelling and writing activities were also addressed. (PS, progress, 1)

A third type of information contained in the progress section of these reports was a description of the performance of the client on specified intervention tasks. The client’s performance was often cast in quantitative terms, as is the following case:

Brad was able to synthesize 3 to 5 phonemes presented verbally with 85% accuracy and minimal clinician cuing. (UNIV, progress, 2)

Sometimes progress was stated in more general terms:

This support has contributed greatly to Benita’s overall communication improvements within the areas of speaking and spelling. Benita has become more confident as a speaker and is highly motivated to become an independent speller as well. (PS, progress, 2)

Recommendations. The recommendations sections of the progress reports were brief, and often cast in a list of three or four items. All of the progress reports in this sample recommended a continuation of therapy under regimens similar to the ones described in the progress section of the report.

It is recommended that Brad continue therapy during the Fall of 1995 semester at this clinic. Continued therapy is also recommended through Brad’s home school district. A combination of direct small group therapy and indirect service (collaborative consultation) with Brad’s classroom utilizing Brad’s academic curriculum is recommended. Direct therapy short term goals should continue to focus on attention, following directions, and auditory memory. (UNIV, progress, 2)

The Logic Underlying Evaluation and Progress Reports

The global-level analysis of evaluation reports revealed an underlying problem-based theme. The client, a person with a possible problem, is introduced with identifying information that usually includes a name, age (birthdate), names of caretakers, and address. The section that follows provides background information, including a statement of concern from a referral source. This introduces the idea that the subject of the report is someone who might have a communication problem. The third section presents irregularities in the client’s family, medical, or developmental history that might have caused the possible problem. Assessment procedures and outcomes are then presented and summarized so as to specify the nature of the problem. Summary sections typically provide evidence for the problem from test results and identify problem areas. Summary sections sometimes venture a guess as to what may have caused the problem. The report then ends by recommending possible solutions to the client’s communication problem, if one was found. The solutions may include further evaluations or particular types of therapy. The evaluation report becomes a coherent whole if all the components are seen as being about an aspect of a client’s suspected problem (see Table 10.2).

Progress reports, while still focused on a client’s problem, differ from evaluation reports in that they do not center around the question of whether or not the client has a problem. Rather, they presuppose the problem and focus on whether or not the intervention being reported has produced positive results. In progress reports, the client is introduced at the outset, often as having an already identified problem (diagnosis). The information in the background history may present the results of an evaluation report in order to establish that a problem exists, or it may presuppose that the problem exists by reporting only on prior recommendations and omitting other historical information. In either case, the emphasis is not on what caused the problem, but on its nature.

TABLE 10.2

Client’s Problem as a Focus for Evaluation Reports

| 1. | Identifying information—person with possible problem is introduced. |

| 2. | Background information (statement of the problem)—nature of the concern is explicated and possible historical origins explored. |

| 3. | Assessment procedures, results, and summary of results—problem areas are outlined. |

| 4. | Recommendations—possible solutions to the problem are presented. |

The focal theme in the organization of progress reports was intervention rather than diagnosis. Progress reports contained descriptions of what was done in therapy, the therapy goals, and the extent to which the client accomplished the therapy goals. Therapy methods were described in detail along with the individual’s performance during the therapy regimens. Progress reports concluded with a description of the person’s future therapy needs and recommendations related to those needs. Their primary emphasis, therefore, was to show progress and argue for the need of continuing therapy (see Table 10.3).

The logic of both evaluation and progress reports, as revealed in the global-level discourse analysis, is problem based, with the subsections of both types of reports building up an argument that the person has a communication problem and is in need of services. The reports are thereby structured to accomplish a similar purpose—to persuade the reader that the client has a problem and is in need of the additional services provided by speech-language pathologists. Thus, the global structuring of evaluation and progress reports does not lead to a difference in the construction of the client’s competence. Both types of reports cast the client in a negative light—as having a possible communication problem in need of remediation.

Descriptions of Clients in Evaluation and Progress Reports

A second type of analysis was done to compare the way clients were described in evaluation and progress reports. Both types of reports contained a section summarizing the current status of the individual, based on the person’s performance on particular tasks or on their presumed specific or general abilities. Descriptions were in the summary sections of evaluation reports and the progress sections of progress reports. Evaluation reports contained descriptions of the client’s performance during the assessment session. Progress reports contained descriptions of the individual’s performance during the intervention period. The following paragraph is from the summary and results section of an evaluation report:

TABLE 10.3

Client’s Problem as a Focus for Progress Reports

| 1. | Identifying information—person with already identified problem is introduced. Problem is presupposed or explicitly labeled (diagnosis). |

| 2. | Background history—problem is sometimes described and medical, developmental, or social background presented. In other instances only the prior therapy recommendations from earlier reports are reviewed. |

| 3. | Progress—goals and nature of therapy are described and person’s response to the intervention. |

| 4. | Recommendations—current problems are outlined and therapy recommendations are made for further work on client’s deficits. |

Andrea is a 4-year, 1-month-old child with a delay in expressive and receptive language. Expressive language is characterized by use of most early developing sentence forms. Phonological and morphological errors decrease her intelligibility. Receptively she apparently grasps part of the sentence, but not the whole. Gestures and visual cues seem to augment her comprehension. (UNIV, progress, 1)

This next paragraph was located in the progress section of a progress report:

Arthur attended 9 out of 14 scheduled therapy sessions. He made progress throughout therapy and produced more intelligible /sh/, /l/, /g/, /k/, and /s/ blends. Overall, Arthur was cooperative and motivated with activities. In addition, he was quite receptive to the clinicians and easily stimulable for productions of the target sounds. (UNIV, progress, 10)

Descriptions of clients’ performance or abilities were identified in both evaluation and progress reports. They were selected from the summary sections of evaluation reports and the progress sections of progress reports. Excluded from this analysis were statements that described other aspects of the assessment or intervention procedures, such as those describing the methods used. Once identified, the performance descriptions were then classified for whether they construed the individual’s ability or performance negatively or positively. Most sentences were classifiable into positive or negative categories by virtue of the language used (e.g., unable vs. able, cooperative vs. uncooperative). Some were able to be classified by examining the contextual information or through inference (inf-pos; inf-neg). A remaining minority of descriptions were indeterminate (ind). Examples of different statements and of the coding procedure are given in Table 10.4 for an evaluation report and Table 10.5 for a progress report. Words or phrases leading to the judgments of negative or positive are in bold face.

TABLE 10.4

Coding of Negative and Positive Statements in an Evaluation Report

| 1. | Andrea is a 4-year, 1-month-old child with a delay in expressive and receptive language. | Neg |

| 2. | Expressive language is characterized by use of most early developing sentence forms. (Inference: 4-year-olds should have later developing forms.) | Inf-neg |

| 3. | Phonological and morphological errors decrease her intelligibility. | Neg |

| 4. | Receptively she apparently grasps part of the sentence, but not the whole. | Neg |

| 5. | Gestures and visual cues seem to augment her comprehension. | Pos |

TABLE 10.5

Coding of Negative and Positive Statements in a Progress Report

| 1. | Arthur attended 9 out of 14 scheduled therapy sessions. | Ind |

| 2. | He made progress throughout therapy and produced more intelligible /sh/, /1/,/g/, /k/, and /s/ blends. | Pos |

| 3. | Overall Arthur was cooperative and motivated with activities. | Pos |

| 4. | In addition, he was quite receptive to the clinicians and easily stimulable productions of the target sounds | Pos |

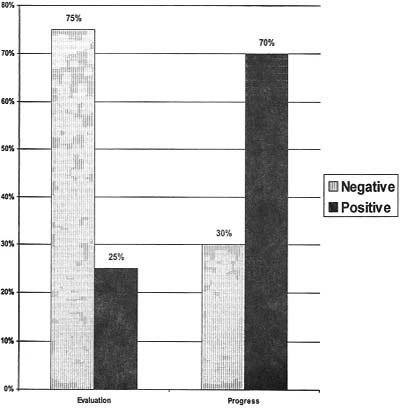

The number of positive and negative statements for each report type was calculated, and the results are presented in percentages in Fig. 10.1. Evaluation reports contained 109 independent clauses describing the client’s abilities or performance. Seventy-five percent (n = 81) were cast negatively, 25% (n = 28) had a positive valence. Progress reports contained 196 performance statements, with 30% (58) framed negatively and 70% (138) cast positively. The results were essentially reciprocal reversals of one another.

FIG. 10.1. Percent of negative and positive statements describing clients’ competence in evaluation and progress reports.

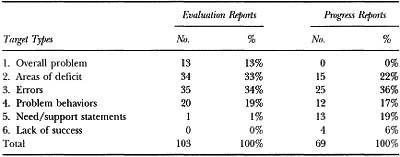

Types of Negative Targets. The negative statements for evaluation and progress reports were categorized according to like types, based on their levels of generality and particular focus. They fell roughly into six different groupings, which are listed in Table 10.6.

The first type of negative description in Table 10.6 is of the client’s overall language performance. This was sometimes cast generally (problem with receptive and expressive language) and sometimes cast as a level of performance (severe, moderate). The existence of a problem was sometimes presupposed (the etiology of the problem is unknown) and other times asserted (X has a significant delay in receptive and expressive language). There were 13 of these statements in evaluation reports and none in the progress sections of progress reports.

A second kind of negative statement targeted areas of deficits, such as domains of knowledge (sentence structures, language form) or type of processing (attending skills). The description was sometimes framed as a specified amount of delay (e.g., level of performance as indicated by test score, age equivalency) and sometimes in more general terms (e.g., mild, moderate, or severe problem in a particular area). There were 34 of these in the evaluation reports and 15 in progress reports, comprising 33% and 22% of the targets in those reports, respectively.

The most frequently found target for both evaluation and progress reports was of more specific performances. Descriptions typically cast these targets as errors, types of errors, or performance problems on particular tasks. This type differed from those identified above (overall descriptions and area of deficit descriptions) in that they pointed to a type of mistake. Some of these descriptions alluded to a lack of specific knowledge (omission of consonants), others pointed to an inability (to associate behaviors), and still others indicated a lack of response (did not respond to any verbal stimuli; no symbolic play). There were 35 (34%) such descriptions in evaluation reports and 25 (36%) in progress reports.

TABLE 10.6

Types, Frequency, and Percent of Negative Targets in Evaluation and Progress Reports

A fourth type of problem is described as inappropriate behavior or insufficient motivation. These descriptions were also specific, in that they described a particular performance, but were not framed as errors or mistakes. There were 20 (19%) of these in evaluation reports and 12 (17%) in progress reports.

The last two categories were found in progress reports, but not in evaluation reports (with one exception). One referred to the amount of support that the individual needed to perform adequately and the second described the individual’s lack of success with an intervention. There were 13 (19%) need statements in progress reports and 4 (6%) statements describing a client’s lack of success with a particular intervention. Table 10.7 lists examples of each target type. The element of each statement leading to its classification is indicated in bold face.

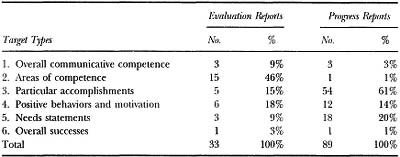

Types of Positive Targets. Another analysis was done to compare the types of positive statements made in evaluation and progress reports for the same six categories identified in negative reports. There were a number of striking differences between positive statements made in evaluation and progress reports (see Table 10.8):

1. Overall communicative competence: There were only a few overall statements about individual’s overall positive achievements in either progress or evaluation reports.

2. Areas of competence: There were a relatively large number of positive descriptions of areas of competence in the summary sections of evaluation reports (15, or 46%) but only one such description in the progress section of progress reports. This differs from the analysis of negative targets, which showed a healthy occurrence of negative references to areas of deficit in both evaluation and progress reports.

3. Particular accomplishments: This category was the reverse of the previous one in that here progress reports showed a high incidence (54 occurrences, or 61%) and the evaluation reports showed a relatively low incidence (5, or 15%). This discrepancy was not evidenced in the negative analysis. In that case, both evaluation and progress reports exhibited a high number of mentions of particular errors or performance problems.

4. Positive behaviors and motivations: This category occurred with similar frequency to the negative statements in both report types. Evaluation and progress reports contained comparable percentages of statements describing positive behaviors and motivations. The numbers and percentages for mentions of positive behavior and motivations are 6 (18%) for evaluation reports; and 12 (14%) for progress reports, as compared with the problem behaviors of 20 (19%) for evaluation reports and 12 (17%) for progress reports (see Table 10.6).

TABLE 10.7

Types of Descriptions Containing Negative Statements and Examples of Each

Overall communication problem

1. Delay in expressive and receptive language

2. Etiology of the communication deficit is not known

3. … little information concerning his … language deficits

4. … does not know how to handle Bob’s problem at home

5. …difficult to ascertain whether or not her decreased language use is related to cognitive factors.

Area of deficit

1. use of early developing sentence forms

2. very poor articulation skills

3. reduced sentence structures

4. language form appears delayed

5. attending skills were impaired

Errors and specific performance problems

1. … she apparently grasps part of the sentence, but not the whole

2. … final consonant deletion

3. … omission of auxiliaries and copulas

4. … immature grasp

5. … difficulty translating orally presented instructions into fine motor acts

Problems with behavior and/or motivation

1. … he was … unspontaneous during these sessions

2. … gave no overt indication of his concern with regard to his performance

3. … appeared confused about his schedule

4. … was reticent to come to the speech room

5. He showed a general lack of response to the environment

Need statements

1. … needed continued teacher reinforcement and coaxing

2. … [to accomplish task, required] maximum clinical support

3. … required physical support to attend to the task

4. … did appear to need the voice output

5. … needed minimal cueing with initial /sh/

Lack of success

1. … although this has been of limited success

2. … remains extremely difficult for Allison

3. … the changes in productions were not significant

4. … is not always able to use those skills functionally

TABLE 10.8

Types, Frequency and Percent of Positive Targets in Evaluation and Progress Reports

5. Need statements: The occurrence of 18 (20%) of need statements for progress reports was comparable to the 13 (19%) negatively cast need statements in progress reports. As with negative targets, there were few need statements found in evaluation reports.

6. Overall learning success: This category, like its counterpart in negative descriptions, had only a few occurrences.

Table 10.9 provides examples of each of the six types of positive target statements. The positive element is indicated in bold face.

Summary of Results of Statements Describing Clients

The findings of this second analysis dealing with the number and types of negative and positive statements complement those of the first analysis, dealing with global-level organization of evaluation and progress reports. Both analyses offer insights as to how agendas influence discourse. The first showed how the overall agendas for evaluation and progress reports similarly influence the global structuring of the two report types. Both evaluation and progress reports reflect the view that the client is the source of the problem. They are structured negatively so as to emphasize the communication problems of the subject and the resultant need for speech-language services. The global analysis of both reports highlighted the client’s communication problem and thus focused on the client’s communication incompetence rather than competence.

The second analysis of statements describing clients demonstrated the influence of a subordinate agenda in the two types of reports. Evaluation reports, intended to demonstrate the need for services, are thereby designed to bring out the negative aspects of the client’s performance. Progress reports, on the other hand, are intended to convey that an intervention program has been successful and needs to be continued. The positive accomplishments of the client are thus made more salient. This positive view, emphasizing competence, is nonetheless cast within an overarching negative view of the client as incompetent and in need of further therapy.

TABLE 10.9

Types of Descriptions Containing Positive Statements and Examples of Each

Overall communication competence

1. Carol’s language competence

2. … potential is there

3. Charles can orally achieve adequate expressive language

4. … demonstrate higher level of language output

5. Arlo shows comprehension of material he has read both aloud and silently

Areas of competence

1. … his content and use appear adequate

2. … adequate attention span

3. … language comprehension is also adequate

4. … peripheral hearing mechanism appears to be adequate

5. Voice, within normal limits

Particular accomplishments

1. … stimulability for several test sounds

2. … used a modified version of … pointing to her mouth to spontaneously communicate something she wanted

3. … was able to delete 80% of the initial syllables

4. … was able to track up to three sounds

5. … was able to follow 2-step simple commands

Positive behaviors and motivation

1. Bob’s cooperative demeanor

2. … was able to make and maintain eye-contact

3. Aaron came willingly to our testing sessions

4. … has imitated as many as 20 signs in a session

5. …was cooperative and motivated with activities

Need/support statements

1. … his attention can be easily diverted to other activities of interest to him

2. …[accomplished X] with maximal clinician cueing

3. … [accomplished X] with clinician support and help

4. … was able to build … sentences without the sentence builder with 80% accuracy

5. … works best when an adult has helped him generate some ideas

Overall impressions of success

1. He has made noticeable improvements …

2. Brad showed continual improvement during the six weeks of therapy

PERSONAL FUTURES PLANS—A REPORT WITH A DIFFERENT AGENDA

In the last decade, a new awareness about disabilities has developed that has led to a new type of report-writing agenda. It has been dubbed the “personal futures plan” or “action plan” (Calculator & Jorgensen, 1994; Mount & Zwernik, 1989; Vandercook & York, 1990; Vandercook, York, & Forest, 1989). The agenda of the personal futures plan is to identify and achieve the wishes of a focus person or to achieve the wishes others have for that person. The plan contains ways to support the focus person to achieve his or her identified life goals. The disability is taken as a given but is not necessarily the primary focus of the report. It is but one of the many things to be considered when eliminating blocks to accomplishing the agenda. Mount and Zwernik (1988) and Mount (1994) describe some of the differences between the process involved in creating a futures plan and that behind an individualized habilitation plan (IHP):

The Personal Futures Plan serves a different function than the IHP. It helps people to reflect on the quality of life of a person with a disability, to explore possibilities, to brainstorm strategies, and generally to reach for outcomes that are beyond the standard procedures and options of traditional services. (Mount & Zwernik, 1988, p. 41)

A positive view of people in personal futures planning helps professionals come to know people with disabilities and appreciate their capacities. This is a discovery process because the gifts, interests, and capacities of people with disabilities so often are buried under labels, poor reputations, and fragmentation of information. (Mount, 1994, p. 99)

Traditional forms of planning are based on the ideal of a developmental model, which … emphasizes the deficits and needs of people, overwhelming people with endless program goals and objectives, and assigning responsibility for decision-making to professionals. … The underlying values of traditional planning communicate subtle messages, for example: The person is the problem and should be fixed. (Mount, 1994, p. 98)

The results of the futures planning process should be integrated as much as is appropriate into the focus person’s IHP (Mount & Zwernik, 1988, p. 41)

A suggested way to develop a meaningful personal futures plan is for a facilitator to pose a set of questions to be answered by a group of hand-picked individuals who will be serving as a support group (the circle of friends) to accomplish the stated goals (Vandercook & York, 1990). A description of how such a plan was developed is provided by Vandercook and York for Mary, an 8-year-old third grader who is a member of a regular elementary school class. The group consisted of nine people who knew Mary well, and a tenth person who was the group facilitator. The group were Mary’s parents, three third-grade friends, her third-grade teacher, her special education teacher, her speech-language pathologist, an exercise consultant, and the school principal. The questions answered by the group and comprising the subheadings of the report (Vandercook & York, 1990, pp. 108–111) were as follows:

1. What is Mary’s history?

2. What is your dream for Mary as an adult?

3. What is your nightmare?

4. Who is Mary?

5. What are Mary’s strengths, gifts, and abilities?

6. What are Mary’s needs?

7. What would Mary’s ideal day at school look like and what must be done to make it happen?

Unlike the evaluation and progress reports analyzed above, Mary’s personal futures plan contained very few statements about Mary’s particular performance abilities. While the global structure allowed for the depiction of Mary’s disability and problems (e.g., What is Mary’s history? Who is Mary?) the format also emphasized Mary’s strengths and abilities and her future life needs (What are Mary’s strengths, gifts and abilities? What is your dream for Mary as an adult? What is your nightmare? What are Mary’s needs? What would [an] ideal day at school look like?)

For that section of Mary’s futures plan which described her past history, the emphasis was not on what went awry in her history or what aspects of her history caused or provided evidence of her disability. Rather it described positive schooling experiences (Vandercook & York, 1990).

This school year Mike (Mary’s father) said the family had really seen Mary “opening up” and acting much more cheerful. He attributed that to Mary’s classmates and the modeling they provided. In contrast, Mary’s models in the self-contained classroom had been limited and consisted primarily of adults. Mike also related how nice it was for Mary to be in her home school. (p. 108)

Positive and negative descriptions of Mary had to do with character traits, life skills, and personal interests (e.g., friendly, bossy, likes to listen to audiotapes). They were made by those who knew Mary well, in contexts of everyday life situations. These descriptions thereby differ considerably from those contained in traditional reports by SLPs, who typically have limited knowledge of the person in home, community or even school contexts. The SLPs’ descriptions tended to focus on the cognitive abilities, language abilities or performance exhibited by the person during the assessment or intervention sessions (e.g., cooperative demeanor, adequate attention span, delayed language form). Finally, the agenda of Mary’s personal futures plan was quite different from that of traditional reports. Personal futures plans are designed to “focus upon the person’s capabilities and an appreciation of his or her unique characteristics. Such a positive orientation assists in designing a hopeful future” (Vandercook & York, 1990, p. 109).

The descriptive terms characterizing Mary (Vandercook & York, 1990) were generated by the team in response to the question: Who is Mary?:

Neat person, does what she’s told, easy going, helpful, third grader, animal lover, warm smile, loves her friends, enjoys her classroom, loving, enjoys the bus, excited, screamer, enjoys Mrs. Anderson, bossy, fun, cute, headstrong, likes babies, follower, shy, stubborn, manipulator, book lover, hearty giggle, easily frightened of things she can’t see, likes to eat, and a friend. (p. 109)

Lastly, the largest section of the personal futures plans was devoted to the team’s description of Mary’s priority needs. The team generated a listing of 30 or so needs, which then became the elements of her futures plan. This emphasis on Mary’s needs is quite different from that in the SLPs’ evaluation. In the case of Mary, the statements were mostly about life goals (needs love, needs more friends, needs discipline). Those that had to do with communication (needs to learn how to say more words, needs to learn more appropriate ways of initiating communication) were cast, along with the others, as a way to better achieve inclusionary practices and life goals. The casting of the communication needs as Mary’s needs (and others’ hopes for her) rather than as therapy recommendations invited a positive (hopes and wishes) rather than negative (deficit) interpretation of them.

OVERALL SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Several findings have emerged from this study of reports written about those with disabilities:

1. The format renditions (major sectional headings) of evaluation and progress reports in the literature were found to be broadly consistent with actual reports written by practicing speech-language pathologists.

2. The formats of the two different types of reports followed a coherent logic. Formats for evaluation reports highlighted the individual’s problem and need for therapy. Subsections served to describe the problem from the referral source, historically, and according to assessment findings, and to provide recommendations for how the problem should be taken care of. Progress reports were designed to emphasized therapy progress and the need for additional therapy. They contained sections describing the nature of the problem, what was done, the results, and continuing therapy needs.

3. The similarities in global-level organization contained in evaluation and progress reports were consistent with an internal logic that reflected a common overall agenda—to identify and remediate the client’s communication problem and suggest a remedy. The organization of both focused on communication incompetence.

4. The differences in the global-level organization of the two report types reflected differences in their agendas. Evaluation reports were aimed at persuading readers of the existence of a problem (concerns, background information, assessment results) and that something could be done about it (recommendations). Progress reports were aimed at persuading readers that particular solutions were successful and should be continued (progress, recommendations).

5. Differences in agendas were also reflected in the way subjects were described within each of the two report types. Evaluation reports contained high percentages of negative descriptions, in keeping with the aim of revealing a subject’s problem. Progress reports contained more positive than negative descriptions, consistent with their aim of showing a subject’s therapy successes.

6. The personal futures plan offered yet a third way to write a report. It did not emphasize identifying or background information, because those for whom the report was written knew the focus person well. Nor did the plan seek a historical cause for the problem, as did the evaluation report. Rather, the emphasis of the futures plan was to identify the client’s needs The personal futures plan as exemplified by the Mary in Vandercook and York (1990) would include descriptions of individuals by their life and York (1990) would include descriptions of individuals by their life companions and would be about character traits rather than the impersonal performance descriptions found in the SLPs’ clinical reports. The descriptions of the individuals would include both positive and negative traits, with an accentuation of the positive competencies rather than the incompetencies.

This chapter has demonstrated that the social construction of the abilities of a person with a suspected or actual communication problem depends on the circumstances in which the targeted individual is being evaluated. This would suggest that the best way to achieve more positive renderings of an individual’s competencies is to alter the agendas of those doing the rendering.

REFERENCES

Beukelman, D., & Mirenda, P. (1992). Augmentative and alternative communication. Baltimore: Brookes.

Calculator, S., & Jorgensen, C. (Eds.). (1994). Including students with severe disabilities in schools. San Diego, CA: Singular.

Emerick, L., & Haynes, W. (1986). Diagnosis and evaluation in speech pathology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Haynes, W., Pindzola, R., & Emerick, L. (1992). Diagnosis and evaluation in speech pathology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hegde, M. (1994). A coursebook on scientific and professional writing in speech-language pathology. San Diego, CA: Singular.

Lund, N., & Duchan, J. (1993). Assessing children’s language in naturalistic contexts. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Meitus, I. (1983). Clinical report and letter writing. In I. Meitus & B. Weinberg (Eds.), Diagnosis in speech-language pathology (pp. 54–69). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Middleton, G., Pannbacker, M., Vekovius, G., Sanders, K., & Puett, V. (1992). Report writing for speech-language pathologists. Tucson, AZ: Communication Skill Builders.

Mount, B. (1994). Benefits and limitations of personal futures planning. In V. Bradley, J. Ashbaugh, & B. Blaney (Eds.), Creating individual supports for people with developmental disabilities. Baltimore: Brookes.

Mount, B., & Zwernik, K. (1989). It’s never too early, it’s never too late. St. Paul, MN: Metropolitan Council.

Neidecker, E. (1987). School programs in speech-language: Organization and management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Pannbacker, M. (1975). Diagnostic report writing. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 40, 367–379.

Sanders, L. (1972). Procedure guides for evaluation of speech and language disorders in children (3rd ed.). Danville, IL: The Interstate.

Vandercook, T., & York, J. (1990). A team approach to program development and support. In W. Stainback & S. Stainback (Eds.), Support networks for inclusive schooling. Baltimore: Brookes.

Vandercook, T., York, J., & Forest, M. (1989). The McGill Action Planning System (MAPS): A strategy for building the vision. Journal of The Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 14, 205–215.

Ward, P., & Duchan, J. (1997). A comparison of information contained in evaluation and progress reports and its relevance for designing computerized formats for writing reports. Unpublished manuscript.