The Social Work of Diagnosis: Evidence for Judgments of Competence and Incompetence

Wayne State University

INTRODUCTION

The medical encounter is centered on diagnosis and treatment: In lay terms, people go to the doctor to find out what’s wrong and what to do about it; in professional terms, the medical history and examination are the basis for the clinical reasoning that arrives at the differential diagnosis with its associated prognosis and course (s) of treatment (Wilson et al., 1991). In abstract terms, diagnosis represents the expertise of the physician, the leap to a conclusion warranted by medical education, training, and experience, and the delivery of that conclusion to the patient and/or family members (Parsons, 1951). In concrete interactions, however, diagnosis represents an interactional achievement of all the participants, not just the physician, although this achievement typically enacts and reflects the asymmetric framework characteristic of institutional encounters (Drew & Heritage, 1992).

In the literature investigating the discourse of medical encounters, considerable attention has been paid to diagnosis as an interactional achievement. Drawing on Byrne and Long’s (1976) description of the generic structure of a medical encounter, Heath (1992) notes that diagnosis occupies the “pivotal position” within a medical encounter: “It marks the completion of the practitioner’s practical inquiries into the patient’s complaint and forms the foundation to management of the difficulties. It stands as the ‘reason’ for the consultation and is routinely documented in the medical-record cards” (p. 238). Heath notes that diagnosis is interactionally achieved in medical encounters: Physicians and patients systematically collaborate in the production and reception of diagnosis. This interactional collaboration, however, tends to preserve the asymmetry of the institutional roles and relationships in the medical encounter. When patients do not respond or respond minimally to the delivery of diagnostic news, for example, Heath argues that their contributions thereby preserve the physician’s expertise over the professional status of the diagnosis and its delivery (p. 262). He notes that even in more complicated cases, where the physician and patient have diverging views of the patient’s condition, their interaction continues to preserve asymmetry. For example, when physicians design a delivery of diagnostic news that they believe is in conflict with patients’ assessment of their own status, they often preface the turn with a token of newsworthiness, like “actually” or “in fact.” When patients want a reassessment of the diagnosis, they manage this goal first by nominally agreeing with the diagnosis and only later presenting new or recycled information that might call for a revision of that diagnosis.

Maynard (1991a, 1991b, 1992) also describes the production and reception of diagnostic news in a study of diagnostic meetings between families and staff at a clinic for children with developmental disabilities. Maynard argues that physicians routinely use what he calls a perspective-display series, especially for the delivery of negative or difficult news. A perspective-display series is similar to a prefacing pre-sequence in ordinary conversations (Schegloff, 1988). In both cases, a speaker provides some opportunity for the recipient of news to actually formulate that news him/herself. The delivery of news, especially bad news, is thereby collaboratively achieved rather than hierarchically imposed: In medical encounters concerning children with developmental disabilities, this ostensibly situates diagnosis as a confirmation of a family’s identification of the child’s problem(s). Like Heath (1992), Maynard (1992) notes that this sequence actually functions to preserve the asymmetry of roles and relationships in the medical encounter. Nonproblematically in cases of converging views between medical professionals and families, and more problematically in cases of diverging views, it is nevertheless the physician and clinic’s view of the problem that ends up as the official diagnosis for the child (p. 337).

In the literature on social aspects of medicine, the concepts of competence and incompetence are most often discussed in terms of the professional knowledge, experience, and judgment of physicians (Del Vecchio-Good, 1995; Freidson, 1986, 1989; Parsons, 1951). Del Vecchio-Good calls physician competence the core symbol of the profession (p. 9). By themselves and by the American public, the majority of physicians are assumed to be competent, delivering appropriate medical care according to the standards of contemporary medicine. The minority of incompetent physicians are supposed to be disciplined by informal and formal means (e.g., hospital credentialing committees, state licensing organizations).

When patients’ and families’ competence are discussed in the medical literature, however, it is most often in terms of compliance. Patients in compliance are following the prescribed treatment and advice of their medical professionals; patients out of compliance are not. (In medicine, there is a huge literature on compliance, with sources such as Gerber & Nehemkis, 1986, and Schmidt & Leppik, 1988; the journal devoted to this topic is entitled The Journal of Compliance in Health Care: JCHC.) But Fisher (1993) discusses competence in broader terms, suggesting that professionals view patients as more or less competent, with competence defined in part as patients’ knowledge or understanding of such things as their condition, their diagnosis, their prognosis, and their treatment options.

Fisher argues that medical professionals’ judgments of their patients’ competence and incompetence sometimes hold very real consequences in terms of treatment decisions. In her study of women referred to university and community women’s clinics, she notes that women who displayed fairly sophisticated understanding about their diagnoses were perceived as competent patients, a judgment which may have played a part in the recommendation of conservative treatment for their conditions. In contrast, women who did not display such understanding, or women who were not given the chance to display their understanding, were perceived as incompetent patients, again a judgment which may have played a part in the recommendation of radical treatment. Patients display knowledge (and therefore competence) in a variety of ways: They may provide sophisticated definitions of their diagnoses, for example, or they may ask informed questions. Patients display their lack of knowledge (and therefore incompetence) in different ways, too: They may not be able to answer questions with definitions of their diagnoses, or they may ask uninformed questions.

All of these investigations raise interesting and important questions about the discourse of diagnosis and the roles that concepts like competence and incompetence may play in the interactions of medical encounters. What all of these investigations have focused on thus far, however, is the presentation of diagnostic news. Maynard’s (1992) data, for example, come from diagnostic meetings with families after a clinic has evaluated and tested a child but before it has begun treatment. Similarly, Fisher’s (1993) data come from initial specialist appointments for patients who have received notice of an abnormal test result, and Heath’s (1992) data come from general practice appointments where diagnosis and treatment are often accomplished within the same encounter. As Ainsworth-Vaughn (1994) points out, however, roles and interactions typically change in the course of long-term relationships between medical professionals and patients and/or families, especially when those relationships are based on a diagnosis of significant disease or disability. (Ainsworth-Vaughn’s data came from medical encounters with cancer patients.)

The focus of this chapter, then, is the complex interconnections of understanding of diagnosis and judgments of competence and incompetence as they are played out in the course of extended relationships between a patient, a family, and a physician or a clinic. By looking at follow-up encounters after a diagnosis has been established, I argue that understanding of diagnosis and the linguistic display of this knowledge actually does a considerable amount of social work in the course of long-term relationships between medical professionals and families. Specifically, I argue that one aspect of this social work is its role as evidence for medical professionals as they form judgments of competence and incompetence. I show how these judgments play a role in the immediate interaction between professionals and families and how they become part of professionals’ subsequent discussions of those encounters.

The data for this study come from a larger investigation of the ways that language surrounds and shapes the social experience of disability in contemporary American society. The following section of this chapter describes two cases studies drawn from the larger study. The two case studies illustrate different connections between understanding of diagnosis and judgments of competence and incompetence. In one case, a family member displays her sophisticated understanding of diagnosis and thereby provides medical professionals with evidence for their judgments of the family’s competence. In another case, family members do not display a sophisticated understanding of their child’s diagnosis and thereby provide medical professionals with evidence for their judgments of the family’s incompetence. The data in these case studies come from two sources: transcripts of conversations between these families and the medical professionals who saw them during particular clinic appointments, plus transcripts of subsequent conversations among clinic staff. The former are fairly typical of data collected in studies of medical discourse, but the latter are less often available to researchers, even participant-observers. The two sources together provide the basis for a triangulated description of the social work of diagnosis.

BACKGROUND AND FRAMEWORKS

Diagnosis represents a linguistic moment of great import in disability: It articulates the key distinction between being abled and disabled; it labels the condition for the purposes of medical, educational, and legal institutions; and it fuses identity and disability in the social experience of the individual and those in contact with him or her (Goffman, 1963; Instad & Whyte, 1995; Lindenbaum & Lock, 1993)1 Diagnosis (or, sometimes, the lack of one) marks the beginning of a medical career, in Parson’s (1951) terms, and it comprises a central component of the background knowledge that patients and families bring to medical encounters. As noted above, researchers have examined the delivery of a diagnosis of disability (Maynard, 1991a, 1991b, 1992), so the focus of this chapter is on the role of diagnosis in follow-up encounters between medical professionals and families who have children with disabilities.2

The data come from fieldwork, which took place from January to December 1994, and involved collecting data through ethnographic participant-observation. One set of participant-observations took place in the urban office of a large health and welfare agency specializing in the care of children with disabilities. During the course of the research, approximately 100 follow-up appointments with a variety of pediatric specialists were observed and recorded at this site (here called the Child Care Clinic). Approximately half of the appointments observed were with White American families and half were with minority families, primarily African-American. All participant-observation sessions were recorded and transcribed in broad form, and analysis was based on these transcriptions plus brief field notes.3

The theoretical framework for analysis of this data comes from recent work in conversation analysis on the nature of talk in institutional encounters, particularly medical encounters (Boden & Zimmerman, 1991; K. Davis, 1988; Drew & Heritage, 1992; Firth, 1995; Fisher & Todd, 1993; Mishler, 1984; G. Morris & Chenail, 1995; Silverman, 1987). As Drew and Heritage (1992) note, within this framework, utterances are considered doubly contextual—they are shaped by the institutional context and they continually renew that context: “[T] he CA [conversation analysis] perspective embodies a dynamic approach in which ‘context’ is treated as both the project and product of the participants’ own actions” (p. 19). In this view, institutions and institutional discourses do not exist in abstract terms alone but are enacted in interactional terms as participants jointly attend to reflecting and creating the context of their situation. Within institutional encounters, then, participants use interactional practices to enact institutional relationships and understandings—in the case of medicine, physicians and patients or families reflexively draw on and enact the institutional discourse of medicine.

Although much conversation analysis research looks at specific linguistic features of talk, such as sequential turn design and topic transitions, Drew and Heritage (1992) suggest that researchers also look at what they call themes: “themes … are often generally distributed across broad ranges of conduct in institutional settings and manifest themselves in and through the features of institutional interaction” (p. 45). Themes that are typical of institutional interactions include asymmetrical social relations among participants (e.g., medical professional vs. patient or family member) and differential knowledge bases across participants (e.g., medical diagnosis vs. lay complaint). These themes can be enacted in a surprising variety of interactional practices (e.g., topic selection and development, turn design, narrative structures, etc.).

The concept of theme thus provides a bridge between the macroanalysis of ethnographic description and the microanalysis of conversational analysis as themes identified through ethnographic observation are shown to be enacted through specific interactional practices. This insistence that themes must be shown to be enacted through specific interactional practices represents a strong constraint on the contextual analyses that are possible within a conversation analysis framework. Following Schegloff (1992), Drew and Heritage (1992) note: “analysis should properly begin by addressing those features of the interaction to which the participants’ conduct is demonstrably oriented” (p. 53).

In the data from this project, one such theme with ethnographic significance and interactional orientation is the understanding of diagnosis. Diagnosis played some part in every medical encounter observed in the research. Delivery of diagnostic news took place both in general and specific terms. Children might have received a general diagnosis of cerebral palsy, say, or muscular dystrophy, and they often received a set of more specific diagnoses as well; for example, a child with cerebral palsy also might be diagnosed with a seizure disorder, a speech disorder, and/or some degree of cognitive impairment. Both medical professionals and families observably attended to diagnosis at different times and to different degrees in medical encounters. Sometimes diagnosis was the central focus of an appointment, as, for example, when a child developed a new set of symptoms or a complication of a condition. At other times, diagnosis was part of the background of an encounter, as, for instance, when a child’s progress or behavior was related to his or her primary or secondary diagnoses.

In order to present a situated discourse analysis of some of the different ways that diagnosis is attended to in medical encounters, this chapter presents two case studies that show different kinds of attending to diagnosis, with significantly different results. Broadly speaking, they represent different points on the continuum of success. In the first case, the family and the physician collaborate easily and successfully on their understanding of the child’s diagnosis. This is especially interesting since the diagnosis is ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), a controversial diagnosis not only in the medical domain but with the general public as well. In the second case, the family and a number of medical professionals do not collaborate successfully on their understanding of the child’s diagnosis of cerebral palsy. In the discussion of each case study, I first show how the understanding of diagnosis becomes a part of the discourse of each medical encounter, enacted more or less collaboratively. I then show how the family’s displayed knowledge of diagnosis played a role in the subsequent judgments that medical professionals made about the relative competence or incompetence of that family.

COLLABORATIVE RELATIONSHIPS IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF ADHD

The existence, diagnosis, and treatment of ADHD are all controversial in contemporary America. Some individuals doubt that ADHD exists, at least as a medical (or neurological) diagnosis, pointing to its status as a clinical diagnosis based on reported behavior rather than on physical signs and/or verifiable tests; others believe that ADHD exists as a condition but is regularly overdiagnosed, blurring the distinctions between behavioral problems and neurological or psychiatric disabilities (Hancock, 1996). ADHD has an interesting, if problematic, history in medicine. Noting that the drugs to control hyperactivity were developed before the disorder was widely identified and diagnosed, Conrad and Schneider (1992) observe that what was called minimal brain damage or hyperkinesis in the 1950s and 1960s has become ADHD, the most widely diagnosed childhood psychiatric disorder of the 1980s and 1990s (p. 157). Conrad and Schneider (1992) provide the standard list of symptoms associated with the medical diagnosis of ADHD:

Typical symptom patterns for diagnosing the disorder include extreme excess of motor activity (hyperactivity), short attention span (the child flits from activity to activity), restlessness, fidgetiness, often wildly oscillating mood swings (the child is fine one day, a terror the next), clumsiness, aggressive-like behavior, impulsivity, the inability to sit still in school and comply with rules, a low frustration level, sleeping problems, and delayed acquisition of speech. (pp. 155–156)

The treatment of choice for ADHD is stimulant drugs such as Ritalin and Cyclert, since these medications deliver the paradoxical results of slowing children down enough to control their impulsivity and increase their attention spans. Hancock (1996) notes that between 1990 and 1996, the number of children taking Ritalin increased two-and-a-half times to over 1.3 million (p. 52).

In the Child Care Clinic, a number of children are followed for ADHD, either as a primary or a secondary diagnosis. The clinic has a well-regarded ADHD clinic, where the diagnosis of ADHD is based on extensive reports from teachers and parents and a battery of physical and psychological tests for the child. The ADHD clinic is under the direction of a pediatric neurologist, here named Dr. Jonathon Brownslee (all names of physicians and family members have been changed). Dr. Brownslee has specialized in learning disabilities and related disorders such as ADHD since the late 1950s. He, too, is well regarded, with an excellent reputation in the clinic and the community. He has contributed to the pediatric literature on ADHD and other topics. He is aware of the controversial status of ADHD as a diagnosis, noting in one conversation with me:

| (1) | ((B: Dr. Brownslee; 0: observer)) | |

| (1a) | B: | There’s a--There’s an interesting editorial in one of the-- I don’t know if it was the Journal of Well Child Medicine or Child Neurology, where there was an editorial about the medicalization of behavior. You know, everything gets subsumed under the medical model. I’m not sure whether that’s good or bad. I don’t know whether ADHD is an entity or not. I’m still not sure. |

| (1b) | O: | You mean a culturally created, or a socially created entity, or-- |

| (1c) | B: | No, like a medical entity, like- - oh, for example, uh, I think you could argue that sickle cell disease is pretty clear, it’s pretty well genetically defined, we have a test for it, we can define it, we can biochemically determine it. Probably, bipolar disorder is probably somewhat uniform, it’s probably genetically inherited, there’s probably some biochemistry to it, you could define it once we get better machines, but I don’t know whether ADHD is the same or not. Or is it just one end of the normal spectrum or caused by the environment, or caused by, you know-- |

| ((some talk about the variety of children diagnosed with ADHD)) | ||

| (1d) | B: | That was the reason I started coming here to this institution, though, is to have a clinic for kids with that sort of problem in learning disabilities, sort of related disorders. |

| (1e) | O: | Um-hmm. |

| (1f | B: | Not everyone in child neurology is interested in that kind of a problem. |

| (1g) | O: | Um-hm. |

| (1h) | B: | There are a few people that-- Many people in child neurology regard that as being pretty soft= |

| (1i) | O: | =Um-hm. |

| (1j) | B: | =not worthy of their attention. |

Dr. Brownslee here articulates his own orientation toward the controversial status of the diagnosis of ADHD. Citing the research literature in medicine in (la), he notes the profession’s concern with the blurred line between behavioral problems and neurological or psychiatric disorders, admitting his uncertainty about whether ADHD is an entity or not. In (1c), he corrects the observer’s orientation toward social construction by explaining exactly what ADHD would have to be in order to be considered a defined and verifiable medical entity, again raising the possibility that it is not a set of physical or psychiatric symptoms but a set of problematic behaviors at one end of the normal spectrum. In (1d)–(1j), he points out that the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD lacks status even among his colleagues in pediatric neurology, again noting that its lack of definition and verification as a medical entity leads some to think of it as pretty soft, not worthy of their attention.

Despite its controversial status in public and professional circles, the diagnosis of ADHD forms the focus or background for many encounters in the Child Care Clinic. Sometimes, the physicians and staff of the clinic and the ADHD children and families show a remarkable degree of shared understanding about this diagnosis, even its medicalized version and its controversial nature. This shared understanding can be displayed in collaborative interaction within the medical encounter, and it can become the basis for positive judgments that result in pro-active medical care. (I define pro-active medical care here as care that goes beyond treatment for the chief complaint forming the specific business of the encounter.) This first case study illustrates these positive interconnections of shared understanding observably attended to in collaborative interaction and positive judgments underlying pro-active consequences. The following excerpt is from an encounter between Dr. Brownslee, a mother, and her cognitively impaired 9-year-old son, Brady, who also has a diagnosis of ADHD. The excerpt is rather lengthy, but each of its seven segments provides examples of the participants’ collaborative attending to the diagnosis of ADHD:4

What is striking about this excerpt is that the physician and the mother collaborate in the display of their shared understanding of ADHD as a medical diagnosis with pharmacological treatment. This shared understanding of the diagnosis of ADHD provides the organizing principle underlying the structure of the encounter and its discourse. That much shared background knowledge underlies this encounter is evident from its first segment, where the mother’s initial utterance assumes the diagnosis of ADHD and its treatment with the stimulant drug Ritalin. In an utterance that is characteristic of long-standing relations between family members and physicians in which family members regularly act on their expertise and physicians routinely accept that expertise (Barton, 1996), the mother herself sets the goal-directed agenda for the encounter in (2b)—we need to increase the medicine. The physician displays his preliminary willingness to accept the mother’s claim, responding with the query think so?, a neutral probe for more information that ratifies rather than challenges the mother’s expertise. Displaying a sophisticated recognition about school as the domain of dysfunction most relevant to ADHD and a savvy understanding about the need to provide evidence for her recommendation from reliable sources, the mother offers two kinds of evidence in (2d)—her own agreement, presented minimally, and the agreement of the school.

The next sequence includes a bit of miscommunication: When the physician requests an elaboration of her own agreement, asking What do you think? in (2e), the mother directs the question to the child in (2f)—Do you think your medicine’s still working? In his response in (2g)–(2h), the physician again identifies teachers and parents as individuals with the information and the expertise to know whether the medication dosages need adjustment. In (2a)–(2h), then, eight short utterances comprising the first segment in this encounter, quite a bit of background knowledge about the diagnosis of ADHD is displayed by both participants: knowledge about drug treatment and the need for careful monitoring and occasional adjustments, and understanding about behavior and reported behavior as the evidence for such adjustments. The physician is careful to observably attend to the expertise of both teachers and parents in school and at home, although the mother herself seems to restrict expertise to professional institutions, especially the school, a pattern that she will repeat throughout the encounter. In sum, although the specific term ADHD has not entered the conversation, the understanding of this diagnosis is the key element of background knowledge drawn on by both participants in the beginning of the encounter.

What is especially interesting about this discourse between the mother and the physician is that its major segments are systematically organized around knowledge of the symptoms and/or treatment of ADHD, sometimes with the mother taking the lead and establishing the focus and sometimes with the physician in the lead. Six subsequent segments in the encounter are organized around ADHD symptomatology and its management through medication. In (2i)–(2t)/Segment 2, the physician and mother discuss attention span and excessive motor activity in the form of fidgety behavior at school, followed by a discussion of medication dosages for a growing child. In (2u)–(2cc)/Segment 3, they discuss aggressive behavior, followed by a truncated discussion of the decreasing effects of medication. In Segment 4, the mother begins an account of sleep disturbances at home in (2dd)–(2ff), a focus on physical symptoms that continues with the doctor’s discussion of growth and weight in (2gg)–(2mm). In (2nn)–(2uu)/Segment 5, the mother and the physician discuss the details of medication management, returning to the central symptoms of ADHD—behavior and attention span. In (2vv)–(2ddd)/Segment 6, the physician brings up behavioral impulsivity at home, although the mother returns the focus to behavior at school. In (2eee)—(2111)/Segment 6, the physician actually adjusts the dosage of medicine, fulfilling the mother’s original goal. In each segment, the symptoms or management of ADHD underlies the topic selection and development.

In Segment 2, the physician begins to explore some of the symptoms of ADHD in (2i), asking about the central symptom of attention span. The mother provides answers to the physician’s question on two levels, first in terms of her son’s primary diagnosis of cognitive impairment in (21)–(2m)—He still can’t read. They’re working with him—and then in terms of his secondary diagnosis of ADHD in (2o)–(2p)—he don’t pay attention that good. And his behavior is worse … more fidgety. In the rest of the discourse, however, she follows up the diagnosis of ADHD, focusing on her son’s attention span and behavior at school and not referring again to his cognitive impairment. Specifically, the mother and physician collaborate here in (2i)–(2p) to establish two symptoms of uncontrolled ADHD—poor attention span and excessive motor behavior (fidgetiness and restlessness). In (2u), the beginning of Segment 3, the mother begins a new segment focused on another symptom of ADHD, providing some information about the child’s aggressive behavior with peers in (2y). She seems to begin summing up her case for an increased dose of medication in (2aa) and (2cc), in (2aa) noting that When he first started the medicine, it’s like having a different kid but comparing it negatively to the present in (2cc)—But it’s not-- (working anymore is perhaps the completion of this utterance). After a pause, though, the mother begins a new segment in (2dd) by bringing up disturbances in sleep behavior, another symptom of uncontrolled ADHD. The physician continues the development of Segment 4 by discussing other physical symptoms of growth and appetite in (2hh) and (211).

In Segment 5, perhaps the most interesting of all the segments since it attends to the public controversy about the diagnosis of ADHD, the mother and the physician discuss the details of medication dosages, with the mother displaying her awareness of the controversial nature of her request for more medicine. In (2qq) and (2rr), for example, she notes that she has not wanted medication exclusively for behavioral control—I don’t want it to slow him down where it’s better for me, you know what I mean?—and in (2ss), she emphasizes that her use of medication is attuned to the appropriate domain—I wanted him to just have enough so he could pay attention and learn. As she deferred to the school’s expertise in Segment 1, here she refers again to the domain of school to reassure the physician overtly that her request is not based solely on home factors. In Segment 6, however, the only segment in which the physician seems to dominate, he himself raises and pursues the topic of behavior at home in (2vv), affirming the mother’s use of the medication not for the control of behavior alone but for the control of the ADHD symptom of impulsivity, which can compromise the child’s safety—’Cause, you know, if he’s kind of impulsive at home … if it helps in that regard, then that’s good. The physician here seems to be offering the mother the ADHD symptom of impulsivity to provide an official symptom for the medical discussion of relevant home behavior. Rather than following up the physician’s attention to home issues, though, the mother finishes this segment by again returning to concerns about school in (2ccc)–(2ddd). Finally, in Segment 7, the physician and the mother end the encounter by collaboratively turning to the details of increasing the child’s dose of Ritalin.

It is striking that in the course of this discourse, the mother and the physician collaboratively attend to almost every one of the symptoms of ADHD as it is medically described, diagnosed, and treated: Conrad and Schneider (1992) mention attention span and hyperactivity with restlessness and fidgetiness (Segment 2); aggression and a low frustration level (Segment 3); sleep disturbances (Segment 4); and impulsivity (Segment 6). Each of these symptoms surfaced overtly in the discourse in (2), as did attention to the controversial status of a diagnosis that may be behavioral rather than physical or psychological (Segment 5). Conrad and Schneider specifically mention the domain of school and the possibility of delayed acquisition of speech and language, which was the primary concern for the mother, who was careful to emphasize repeatedly her desire for her son to be able to learn. Even though the term ADHD was not even mentioned in the discourse, both the mother and the physician attended to it throughout, using its medical description as an organizing principle for the discourse. In a display of a sophisticated understanding of the medical model of ADHD, every single piece of information the mother provided is relevant to a medical description of ADHD. Both the physician and the mother, it appears, are working with a shared understanding of the medical model of ADHD as background knowledge: The mother has displayed an expertise about ADHD that seems to be a fairly precise match with the physician’s medical model of the disability. Within this high degree of shared understanding about the child, the disability, and the connection between the medication and the behavior of the child, the physician comfortably accedes to the mother’s stated goal for the encounter—he increases the dose of medication in Segment 7.

After the appointment, Dr. Brownslee met the director of psychology at the clinic. He begins a conversation about Brady by summarizing the current status of medications for school and home, but the psychologist’s response in (3b) is especially interesting:

| (3) | ((B: Dr. Brownslee; S: Dr. Sander, psychologist)) | |

| (3a) | B: | He was only getting five milligrams of Ritalin. And um, apparently it helps enough that the school told Mom he shouldn’t come if he doesn’t get it. She’s been giving it to him on the weekends, too. |

| (3b) | S: | She’s come so far. |

| (3c) | B: | Yeah. OK. Yeah. I wondered, have we got any spots left in the summer still, summer programs? He’s going to be going to a day camp anyhow so-- |

| ((some talk about slots in summer programs)) | ||

| (3d) | B: | ((looking at chart)) He came up with an EMI, I see. ((EMI = Educable Mental Impairment5)) |

| (3e) | S: | I remember his feedback. There was a special ed teacher with her at the feedback who told us that she didn’t believe it. That we were wrong. That she’d been teaching for 20 years and she [really-- |

| (3f) | B: | [Would it be useful to test him again? |

| (3g) | S: | Sure. Is he in a regular classroom? |

| (3h) | B: | You know, I’m-- I’m not sure. I’m sorry, I’m not-- |

| (3i) | S: | I’m not either. ((laughing)) Why should you be sorry for something on my caseload? He was in a special ed room in a temporary placement when we saw him. |

| (3j) | B: | No, I’m not sure. Last time I saw him was in November. Why don’t we have her back and I can take another look at him? |

| (3k) | S: | OK. |

| (31) | S: | His scores may have come up. If he is in special ed and his scores have come up too far we just won’t share them with the school so they won’t decertify him. |

| (3m) | B: | ((shout of laughter)) |

| (3n) | S: | It’s true. |

| (3o) | B: | Dishonesty is rampant! |

| (3p) | S: | It’s a private eval. It’s up to them whether they’ll share them with the school district. I don’t want to decertify him. ((eval - abbreviation for “evaluation”)) |

In (3b), the psychologist makes a specific remark about the mother, offering the judgment that She’s come so far, and the physician agrees with this judgment, using multiple agreement tokens. They then go on to discuss Brady’s case in a very pro-active way, exploring the possibility of his attending a summer program at the Child Care Clinic, and even considering the possibility of repeating his psychological testing to confirm the diagnosis of cognitive impairment at the level of EMI. In a savvy awareness of the circumstances of special ed for a child with ADHD who might benefit from smaller classes and individual attention, the psychologist half-seriously suggests that Brady exists within contradictory diagnoses, especially if his diagnostic certification in the schools is jeopardized by an improved medical/psychological diagnosis. What is interesting about the sequence in (3) is that all of the pro-active efforts on behalf of the child seem to follow from a positive judgment about the mother. It is as if the performance of competence during the appointment triggers not only a successful medical encounter but also a positive judgment about the mother’s parenting, which then leads to more services for the family. Although the staff does not use the expression in this particular case, this excerpt represents the expression in frequent use at the Child Care Clinic—“She’s a good mom”—an expression that stands as a judgment of competence within a compliment.

In conclusion to the discussion of this case, it is interesting to speculate a bit about the hypothetical circumstances mentioned by the psychologist in (3l)–(3p): In this case there seems to be a stated willingness to go beyond categorical definitions of disability and supply services perceived as appropriate to the particular child. In particular, the medical professionals imply that they could justify entering a state of diagnostic collusion or even conspiracy with the mother, reversing the primary-secondary order of Brady’s label from a cognitively impaired boy with ADHD to a boy with ADHD and related learning difficulties. The school system provides services for the first diagnostic label only, despite the obvious benefits for a child with the second label. (At this time, the state of Michigan does not recognize ADHD as a certified disability, one that would receive services from the state. Despite many attempts on the part of parents’ groups to change this, the schools and state have held firm, perhaps in fear of the tremendous numbers of children who would then enter the special ed program with a diagnosis of ADHD.) The physician and psychologist here are attending to the complexities of the diagnostic label of ADHD, which can have one set of implications in a medical setting but quite another set of implications, some problematic, in a school setting. Their discussion reflects the importance and complexity of diagnostic labels in the world of disability, labels that organize not only the series of medical encounters which are part of the life of disability but also the services from educational institutions which are intended to make that life an independent and productive one.

ADVERSARIAL RELATIONSHIPS IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF CEREBRAL PALSY

The previous case study presented an exceptionally collaborative interaction and admirably positive follow-up, but relationships between medical professionals and families are not always quite so smooth. The following case study is almost the exact opposite of the previous one. Instead of a complex and sophisticated shared understanding of diagnosis, there are significantly diverging understandings about what it means to have cerebral palsy. Instead of a collaborative interaction leading to positive judgments and pro-active consequences, there is a contentious interaction leading to negative judgments and problematic consequences.6

The particular site for this case analysis is also the Child Care Clinic, but this case is drawn from an observation in the clinic’s CMS clinic—the Children’s Multidisciplinary Specialty clinic—which is funded by the state’s Special Health Care Services program. The CMS clinic arose in response to a complicated set of circumstances that often occur as a result of moderate to severe disability—a necessary involvement with many medical professionals in different specialties. A child with a moderate or severe disability, such as cerebral palsy or spina bifida, routinely needs to see a neurologist, a physiatrist, an orthopedist, an ophthalmologist, and perhaps a pediatric psychologist, as well as a regular pediatrician; in addition, he or she usually has frequent evaluations and treatment sessions with physical and occupational therapists and speech pathologists. This need for multiple appointments with specialists can be time-consuming and exhausting, especially for families in poverty who often have transportation problems. Even more problematically, multiple encounters with this many medical professionals can create a kind of too-many-cooks situation, where no one person seems in charge of coordinating specialty care and of communicating with family members and other institutions, such as schools and social service agencies. The CMS clinic is intended to remedy these logistical and institutional complexities by establishing a single visit with multiple specialists, resulting in a coordinated plan for medical professionals, families, and other institutions:

Within a half-day visit, a minimum of eight different professionals evaluate the child and assess family concerns and needs.… An integrated treatment plan is provided to the family and their community pediatrician. (“Care for the Disabled Child,” Child Care Clinic brochure)

The Child Care Clinic is rightly proud of its CMS clinic, pointing to its potential for coordinating complex health and welfare services for families.

It is important to note here that although this case study represents a particularly problematic encounter, it is an exception to what I found in the majority of my fieldwork at the Child Care Clinic. The clinic is a unique and important institution, and their CMS clinic is an innovative and effective deliverer of health care. The clinic provides services for children and families of all income levels and social classes, serving families with any insurance, including Medicaid, or with no insurance at all. Families that come to the clinic include the urban poor and working class; the median income of the families at the Child Care Clinic is less than $10,000 (“1992 Facts and Figures,” Child Care Clinic brochure). Nevertheless, the medical care provided to these families is of extraordinarily high quality, and the health and welfare professionals are concerned and caring individuals. Most of the relationships between staff and families are mutually respectful and productively collaborative, as illustrated in the first case study. But adversarial relationships sometimes develop between the clinic staff and families, and the following analysis is intended not to excoriate individuals on either side but to explore some of the problematic interactions where judgments of competence come into play.

The African-American family in this particular CMS visit has a 3-year-old son named Xavier, who has been diagnosed with severe cerebral palsy. As of this visit, Xavier’s physical development has been severely delayed—he does not roll, sit, crawl, stand, or walk independently. His language development is severely delayed as well—his speech consists mostly of sounds, with only one word, Dada. The first excerpt is from the end of a session with the therapists who are evaluating Xavier for possible referral to physical therapy (for gross motor development), occupational therapy (for fine motor development), and speech therapy (for language development). Each therapist has examined Xavier, asking about his current therapies, his adaptive equipment, and his general health and progress. At the end of the team examination, there is an opportunity for parents to ask questions, state concerns, and raise issues. The end of the interview by the team of therapists thus nominally turns control of the encounter back to the parents:

| (4) | ((B: Bridgit, occupational therapist; F: father)) | |

| (4a) | B: | Well, what can we do for you guys today? How could we help? You only have us for a real short time, though, today. |

| (4b) | F: | Well, physically-wise the only problem I have is that he’s just too tight. He’s too-- Ought to have some type of physical therapy that could cause him to loosen. You see how relaxed he is now? He’s not like this all the time. Seem like when he get excited, his whole body just tightens up. |

| ((talk about tightness and about hand activities)) | ||

| (4c) | B: | Does Xavier-- Do you know, does he have cerebral palsy? Is that why he-- his muscles are doing what they’re doing? [Is that what’s happening? |

| (4d) | F: | [Um-hmm. |

| (4e) | B: | OK. So, uh, I’m still on the muscle thing, ’cause you guys were talking about it, and also with the hand, and it seems like there’s still the muscle thing in the hand, just like there is in the legs. OK, it sounds to me, or looks to me like he’s a little person who’s, you know, got like an all or nothing thing, you know, he’s either all, you know, relaxed, and we call that hypotonia, or low tone. And then when he wants to move, or he wants-- or he gets excited it’s like too much. You know, it’s-- |

| (4f) | F: | He take it overboard= |

| (4g) | B: | =He overdoes. Right. And he can’t help that. |

| (4h) | F: | Uh-huh. |

| (4i) | B: | You know, that happens because his brain is not-- It’s not telling his muscles to grade that properly. Some of that isn’t ever going to go away. In other words, there’s not a physical therapy thing we can do to say it’s going to get all better, you know, it’s just magic. Because it’s in his brain that’s doing this. But there is some, you know, things we can show you that will help-- um, help you a little bit to help to reduce its- - the tone a little bit. And he also needs to work on some muscle strengthening, which is what you guys were doing in physical therapy. |

The occupational therapist’s turn here to the space for the parents’ concerns begins in (4a) with the caution that You only have us for a real short time, though, today, a warning that advises the parents not to try to ask too much during their limited moments of control over the encounter.

The ensuing exchange seems to reflect significantly different understandings of Xavier’s diagnosis, at least from the therapist’s perspective (cf. discussion of (5) below). In (4b), the father raises a specific concern; displaying his diagnostic understanding by using a term from the vocabulary of therapy, he characterizes Xavier as too tight. It is interesting here that the father begins by showing a rather sophisticated knowledge of an appropriate concern for the team that is in the room at the moment: Problems with tone are exactly the domain of physical and occupational therapy (i.e., note that the father does not begin with a concern about the child’s breathing, the domain of ENT specialists, or his continuing seizures, the domain of pediatric neurology). The therapist, rather than orienting her discussion of tone in terms of the father’s knowledge of his child’s condition, constructs an explanation of tone in (4c)–(4i) that seems to assume that the father is unknowledgeable about cerebral palsy and unrealistic in his expectations of therapy. She checks on the child’s diagnosis of cerebral palsy in (4c), and she orients her remarks initially to the father’s concern in (4e)—I’m still on the muscle thing, ’cause you guys were talking about it. She then begins to explain Xavier’s state of relaxation, first in nontechnical terms—the muscle thing [is] an all or nothing thing—and then begins to restate this description in medical terms, saying of Xavier’s state of relaxation, we call that hypotonia, or low tone.

In explaining that problems with low and high tone will be a consistent problem, not under Xavier’s control, though, the therapist goes on to explicitly construct a representation of the father’s expectations as unrealistic in (4i). But the father did not say that he expected physical therapy to make Xavier get all better or that he thought physical therapy was magic. Instead, the therapist constructs a position of ignorance for the father, rather obscurely summing up the medical understanding of cerebral palsy as permanent damage to the motor pathways of the brain by saying Because it’s in his brain that’s doing this.

The therapist continues to articulate this view of the father as uninformed in other settings. In the staff meeting after the appointment, she says of the exchange she had with the father:

| (5) | ((B: physical therapist)) | |

| (5a) | B: | The father’s main concern is to come here and help the kid to crawl and walk. The father believes that this is the only thing that’s wrong with the kid, he’s got a normal mind but he’s in a screwed-up body. I asked him what he knew, because he said when [Xavier] gets excited, he stiffens right up, so he wants us to fix that. I said, do you understand what cerebral palsy is--? |

Again, the therapist’s discourse constructs the father as ignorant about the disability and uninformed about its treatment. In (4), however, the father did not say that he expected therapy to fix Xavier, he actually articulated a more complex expectation, that Xavier Ought to have some type of physical therapy that could cause him to loosen. But the semi-sarcastic rhetorical question of the last utterance in (5)—I said, do you understand what cerebral palsy is?—reveals the therapist’s negative judgment about the father’s competence, particularly in terms of his understanding of Xavier’s diagnosis.

In the excerpt in (4), the therapist may be attempting to realign the family’s construct of cerebral palsy to match a medical model, but her explanations in (4e) and (4i) are problematic in several ways. First, she does not provide a comprehensive or comprehensible explanation of the relationship between cerebral palsy and muscle tone. She begins to explain low tone, or hypotonia, but she does not finish the comparison to high tone, or hypertonia, nor does she explain clearly why it is that many children with cerebral palsy alternate between hypotonia and hypertonia. Further, the therapist’s explanation of the relationship between the brain damage of cerebral palsy and the amount of conscious control Xavier has over his muscles is obscure at best. In this and other exchanges the medical staff seems eager to assure the father that Xavier has no control over his tone fluctuations, but they don’t offer a neurological or physiological explanation of this relationship. Instead, they concentrate on a simplistic insistence that the father not blame Xavier for his condition. The father and the therapist seem to be in a Catch-22 communicative situation here. The therapist makes negative judgments about the father’s lack of diagnostic understanding, but the father is never given enough comprehensible information to develop his understanding of a medical model of cerebral palsy. The end result is that the interactional undertones in (4) are oppositional rather than collaborative—adversarial undertones that surface again in the therapist’s recollection of the conversation for a meeting with her medical peers in (5).

Another exchange that is similar to the previous one occurs later in the appointment during Xavier’s examination by the team pediatrician:

The question-answer sequence between the pediatrician and the mother in (6a)–(6b)/(6d) is a typical sequence in specialty medical encounters related to disability. Family members are expected to report accurately the opinions of other specialists who have seen their child, which the mother does in (6b) and the pediatrician acknowledges in (6d). The father’s answer in (6c) and its elaboration in (6e)/(6g), however, complicates this basic sequence. In (6c) he presents his own opinion—I do—and he then begins his own explanation of Xavier’s diagnosis and prognosis by explicitly setting aside a medical opinion in (6e): I don’t know what the doctors say, but. … The pediatrician abruptly interrupts the father’s description of the child’s prognosis, however, in (6h), perhaps enacting her judgment that the father is unrealistic with dismissive remarks that shift the burden of improvement to the school system rather than the medical system. The pediatrician does not even attempt to respond to the father’s contributions here, effectively ending the conversation with the adult by turning to the nonverbal and (apparently) noncomprehending child and using baby talk to ask Xavier Who’s on your bib there, sweetie. In sum, neither the therapist in (4) nor the pediatrician here (in 6) gives any interactional credence to the father’s understanding of his child’s diagnosis and prognosis, dismissing his understanding in oppositional rather than collaborative terms.

Yet another sequence like (4) occurs at the end of the pediatrician’s visit. In (7a) she nominally turns control of the encounter over to the parents, and in (7b) the father reiterates his concern about Xavier’s tightness:

The pediatrician here interrupts the father’s discussion of Xavier’s tightness to check on the child’s diagnosis in (7c)–(7h) and tries to relate Xavier’s problems with muscle tone to his diagnosis in (7j), again interrupting the father’s attempt to state what he knows about his child’s diagnosis. But like the therapist in (4), she constructs a version of the father’s understanding that represents him as uninformed about the diagnosis and unrealistic in his expectations. When the pediatrician notes that We’re not sure right now how much of that he’s going to be able to control, she implicitly dismisses the father’s suggestion that Xavier receive help in loosening up so that his body can stretch out and he can learn to turn over and crawl. But the father’s concern that Xavier’s body may someday not stretch out is a legitimate one with respect to cerebral palsy: Preventing muscle contracture through stretching is an important component of a physical therapy regimen. And even though the father’s expectation that Xavier will learn to turn over and crawl is more problematic with respect to his degree of impairment from cerebral palsy, his concern with Xavier’s significant physical delays is also a legitimate one.

In this exchange, though, the pediatrician does not follow up either of the father’s expressed concerns or their underlying displays of diagnostic understanding. Instead, she presents an uncertain prognosis framed within the medical model of treating a child with cerebral palsy with intensive therapy so that he or she can establish control over gross and fine motor muscle processes the best he can. Like the therapist in (4), the pediatrician seems to be trying to realign the family’s understanding to a medical model, and within a medical model the prognosis of cerebral palsy is so uncertain—Now, we hope that problem will not get worse, OK—that attention is directed to the incremental advances of a therapy program—through a lot of therapy, OK, we’ll be able to work with him. The interaction here nevertheless remains more adversarial than collaborative. The pediatrician seems to oppose the father’s expectations, responding to them as unrealistic and uninformed rather than working with them as a reasonable understanding of his child’s diagnosis. Her final explanation is punctuated with tokens of OK, not used as collaborative checks on understanding but as somewhat aggressive demands for acquiescence to this particular explanation. Rather than waiting for the father to provide back-channel OKs in an indication of his understanding and acceptance, she provides them herself, thereby preempting any contribution from the father. (For more on the use of “OK” as a constraining device in medical discourse, see Beach, 1995.) In sum, this interaction, with its interruptions, its lack of development of the father’s contributions, and its imposition of a medical model without alignment to a family model seems characteristic of an adversarial relationship rather than a collaborative one.

That the relationship being developed here is an adversarial one is reflected in the discussion during the staff meeting after the encounter. The medical team’s impression of the father as uninformed and unrealistic in his understanding of his child’s diagnosis and prognosis is addressed at length by one physician at the meeting. In response to the occupational therapist’s description of the father in (5), the physiatrist who saw Xavier, says:

| (8) | ((Ph: physiatrist; B: occupational therapist; P: pediatrician; N: nurse)) | |

| (8a) | Ph: | Well, you know what? This-- It’s a slow process and that. I mean, if somebody says something like that to me, it’s just showing what he can’t do over time, not what he can do. And I wouldn’t even address yes or no on that. I’d say, listen, you know, if that’s a goal you have, then we’ll try to do all the little components and see what we can get to. If that can be obtainable, that’s fine. If you want my opinion on it, you know, I’ll give it to you, but right now I’m not going to offer it. But he’s going to be casted for his AFOs, his feet have fairly good range, he’s tighter in the hamstrings. I need to prove that they will come back, because there’s some reason when I first saw him that I didn’t think he’d use them, be very compliant. So- |

| (8b) | B: | They have bad attendance and they missed an eval. |

| (8c) | N: | [But they say it’s ’cause he’s always in the hospital. |

| (8d) | P: | [OK, then that’s what it must have been. |

| (8e) | P: | And he has been. |

| (8f) | N: | But they need to call. I mean, the problem is-- |

In (8a), the physiatrist incorporates three important components of a medical model of disability in his response (Nagler, 1993). The first aspect of a medical model of disability that emerges from this physician’s discourse is that prognosis is uncertain. Although experience with many children with cerebral palsy can provide a background for forming an opinion about whether a given child will ever sit, crawl, stand, or walk independently, medical paternalism also dictates that it is best to treat every child’s potential positively, not focusing on what he can’t do over time [but on] what he can do. The consequent attention to progress through therapy is the second aspect of a medical model of disability that emerges from this physician’s talk. Given the uncertainty of prognosis, experience shifts the focus to therapeutic goals. Even if the physician believes that the father’s goals of independent crawling and walking are unrealistic, he shows his willingness to incorporate them into the therapeutic model, but operationalizing the goal as trying to do all the little components and see what we can get to. The long-term goal thus is subordinated to the short-term goals in a therapeutic sequence.

The final component of a medical model emerging from the discourse of the physician here, though, involves compliance. In this particular case, the physiatrist connects compliance and competence in a negative judgment: … there’s some reason when I first saw him that I didn’t think [they’d] be very compliant. Given the importance of a therapeutic treatment for a child to reach goals, a family’s compliance with that program is essential. This family, however, is judged as not compliant or competent, first by the physician in (8a), and then seconded by a variety of staff members in (8b)–(8f). The family is finally presented as an intractable problem in (8f), one which trails off without a solution as the problem is--.

One final excerpt from this encounter comes from the end of the appointment and summarizes the results of the visit:

| (9) | ((N: nurse; M: mother; F: father)) | |

| (9a) | N: | You’ll get a report from us in a couple of weeks. OK? And it’ll have something in it from everybody who’s seen him today. And then it’ll have recommendations at the back, OK, with, urn, phone numbers, you know, if we’ve referred him somewhere, there’ll be the phone numbers on there that you need to know. OK? And then if you have any problems with that-- Um, has Miss Thomas been in, the social worker? |

| (9b) | M: | Uh-huh. |

| (9c) | N: | OK. And then if you have any problems with it, you can either contact myself or Miss Thomas. And our phone numbers will be on that report, too. OK? |

| (9d) | F: | Um-hmm. |

This exchange promises that the family will receive a coordinated plan from the clinic. But whether it provides the integrated care that the clinic was designed to provide is questionable. The responsibility of the staff is to prepare a report, which the nurse promises to deliver in (9a). But no more than that is offered. The nurse offers the report with constraining OK tokens, not giving the family any interactional opportunity to do anything but passively wait to receive the report. Her offer of help from herself and the social worker in (9c) is in the form of a contact by phone only. There is no offer here to bring the family back to explain the report, to assist in fulfilling its recommendations, or to ask any questions the report may raise. The onus is now solely on the family to follow up all of the referrals recommended by the team; all the team has to deliver is phone numbers. The family is expected to rely on its own logistical skills to interpret the report and follow up on its recommendations. Given the fact that the family is already out of compliance and has been informally judged as incompetent, particularly in their understanding of their child’s diagnosis and prognosis, relying on their logistical skills leaves in place precisely the situation the clinic is designed to overcome: The family is faced with an extraordinarily fragmented situation of specialty medical care, care for which they alone are responsible. The report is the designated product of the clinic; in its staff meeting, the team is conscientious about preparing its recommendations. But the simple delivery of a report, especially in comparison to the delivery of additional services in the previous (ADHD) case study, seems more reactive than pro-active, more related to duty than to active caring, and more characteristic of a distant relationship based on mutual mistrust than a close relationship based on mutual trust.

In sum, the contrasts between the two case studies presented here are dramatic. In the first case, the interaction is mutually collaborative, especially with regard to the understanding of the diagnosis of ADHD. The physician and the mother seem to draw on similar understandings of ADHD, and the physician repeatedly invites the mother to articulate her own expertise, even though the mother routinely defers to the expertise of the school and the physician. Perhaps as a result of the shared understanding displayed in this collaborative interaction, the physician’s subsequent judgment about the mother is a positive one of competence (he agrees overtly with the psychologist’s judgment that the mother has come so far), and the care that this family receives is notably pro-active (they are called back to receive more services).

In the second case, the interaction is not mutually collaborative, especially with regard to the understanding of the diagnosis of cerebral palsy. The family, particularly the father, and the medical team seem to draw on very different understandings of severe CP, and the interaction is oppositional and adversarial (the father is repeatedly interrupted, his opinions and understandings are neither solicited nor substantively incorporated into the medical team’s explanations, and the medical team’s explanations are delivered impositionally). Again, perhaps as a result of the lack of shared understanding displayed by the father in this contentious interaction, the medical team’s subsequent judgments about this family construct the family as noncompliant and incompetent, and the care this family receives is more perfunctory than pro-active (they are delivered a report with nominal but not substantive offers of assistance).

In both cases, these judgments of competence and incompetence are formed based in part on the details of the linguistic interaction between participants, as the discourse of medicine is more or less collaboratively enacted—very successfully in the first case, but less so in the second. The actual interaction among participants then, holds significant consequences for the relationships being established and enacted by these participants, relationships that will be long-lasting ones.

CONCLUSION

This chapter has considered the understanding of diagnosis in medical discourse, arguing that the understanding of diagnosis has consequences for the relationships between medical professionals and families. Not surprisingly, in the asymmetric realities of institutional encounters, a family’s display of understanding of a medical model of diagnosis is much appreciated and richly rewarded in a clinical setting. The first case study illustrated the successful enactment of shared understanding and collaborative interaction, leading to positive judgments of competence within cooperative and respectful relationships. Perhaps, again not surprisingly, a family’s lack of understanding of a medical model of diagnosis, or its resistance to that model, is neither appreciated nor rewarded in a clinical setting. The second case study illustrated the problematic enactment of diverging understandings and contentious interaction, leading to negative judgments of noncompliance and incompetence within adversarial relationships.

This chapter has argued that understanding of diagnosis is an important part of long-term relationships between medical professionals and families, suggesting that the connection between understanding, interaction, and judgment is an important and complex dimension of these relationships. More specifically, it argues that the current view of compliance of patients and, especially, families may be too narrow a perspective. Competence is a broader concept, shown here to include knowledge and understanding in connection with compliance. Competence may include other aspects as well. One physician who participates in this research project as an informal consultant notes that his judgments of competence also are based on what he perceives as an appropriate emotional response to a diagnosis. The implications of this work for future research, then, point to further investigations of the interconnections between the discourse of medical encounters and the concepts of competence and incompetence.

This research also has implications for both parties in the institutional encounters of medicine for thinking about communication. For medical professionals, this research suggests how many expectations they may unconsciously hold about the knowledge and understanding they want families to have. These case studies clearly show that communication is best facilitated when both professionals and families share some degree of understanding of the medical model of a particular diagnosis of disability. These studies also show, however, that knowledge of the medical model of disability in general or of a specific diagnosis in particular is communicated obliquely and often incompletely (e.g., the physician in the first case obliquely offers the symptom of impulsivity as a way for the mother to think about ADHD-related behavior at home; the therapist in the second case begins to explain types of tone but doesn’t complete her explanation). The end result can go beyond the productive asymmetry of an institution where considerable expertise is imparted to families seeking assistance. Problems emerge if physicians and other staff members do not stop to educate families about the medical understanding of a diagnosis, or if they do not guard against automatic dismissal of views of a diagnosis that are not in precise alignment with the medical view.

Similarly, for families, this research suggests that they make systematic distinctions, when necessary, between a medical model of diagnosis and their agreement or disagreement with it. Sometimes a medical model works not only for institutional encounters but for everyday life, as implied by the first case study; but occasionally diverging views of a diagnosis and its prognosis lead to significant misunderstandings with potentially negative consequences, such as the adversarial relationship being formed between the medical staff and the family in the second case study. In the case of conflict, it is important for families and for professionals to lay out their understandings and concerns explicitly so that the mismatches between models, between understandings, between priorities, and between styles of communication can be addressed directly. Social judgments, especially negative ones, are hard to overcome, and the relationships between medical professionals and families are best based on judgments of competence rather than incompetence.

REFERENCES

Ainsworth-Vaughn, N. (1994). Is that a rhetorical question? Ambiguity and power in medical discourse. Journal of Medical Anthropology, 4(2), 194–214.

Antaki, C. (1994). Explaining and arguing: The social organization of accounts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Atkinson, J., & Heritage, P. (Eds.). (1984). Structures of social action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Barton, E. (1996). Negotiating expertise in discourses of disability. TEXT, 16(3), 299–322.

Beach, W. (1995). Preserving and constraining options: “Okays” and “Official” priorities in medical interviews. In G. Morris & R. Chenail (Eds.),. The talk of the clinic: Exploration in the analysis of medical and therapeutic discourse (pp. 259–289). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Black, K. (1996). In the shadow of polio: A personal and social history. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Boden, D., & Zimmerman, D. (Eds.). (1991). Talk and social structure. Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Byrne, P., & Long, B. (1976). Doctors talking to patients: A study of the verbal behaviors of doctors in the consultation. London: HMSO.

Chafe, W. (Ed.). (1980). The pear stories: Cognitive, cultural, and linguistic aspects of narrative production. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Chafe, W. (1993). Prosodic and functional units of language. In J. Edwards & M. Lampert (Eds.), Talking data: Transcription and coding in discourse research (pp. 33–44). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Clifford, J., & Marcus, G. (Eds.). (1986). Writing culture: The poetics and politics of ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Conrad, P., & Schneider, W. (1992). Deviance and medicalization: From badness to sickness (Expanded ed.). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Davis, K. (1988). Power under the microscope: Toward a grounded theory of gender relations in medical encounters. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Foris.

Davis, L. (1995). Enforcing normalcy: Disability, deafness, and the body. London: Verso.

Del Vecchio-Good, M. J. (1995). American medicine: The quest for competence. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Drew, P., & Heritage, J. (Eds.). (1992). Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Featherstone, H. (1980). A difference in the family: Living with a disabled child. London: Penguin.

Ferguson, P., Ferguson, D., & Taylor, S. (Eds.). (1992). Interpreting disability: A qualitative reader. New York: Teachers College Press.

Fine, M., & Asch, A. (Eds.). (1988). Women with disabilities: Essays in psychology, culture and politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Finger, A. (1991). Past due: A story of disability, pregnancy and birth. Seattle, WA: Seal Press.

Firth, A. (Ed.). (1995). The discourse of negotiation: Studies of language in the workplace. Oxford, England: Elsevier Pergamon.

Fisher, S. (1993). Doctor-talk/patient talk: How treatment decisions are negotiated in doctor-patient communication. In S. Fisher & A. Todd (Eds.), The social organization of doctor-patient communication (2nd ed., pp. 161–182). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Fisher, S., & Todd, A. (Eds.). (1993). The social organization of doctor-patient communication (2nd ed.). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Freidson, E. (1986). Professional powers A study of the institutionalization of formal knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Freidson, E. (1989). Medical work in America: Essays on health care. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Gallagher, H. (1990). By trust betrayed: Patients, physicians, and the license to kill in the Third Reich. New York: Henry Holt.

Gallagher, H. (1994). FDR’s splendid deception (Rev. ed.). Arlington, VA: Vandamere Press.

Geertz, C. (1983). Local knowledge: Further essays in interpretive anthropology. New York: Basic Books.

Geralis, E. (Ed.). (1991). Children with cerebral palsy: A parents’ guide. Rockville, MD: Woodbine House.

Gerber, K, & Nehemkis, A. (Eds.). (1986). Compliance: The dilemma of the chronically ill. New York: Springer.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hancock, L. (1996, March 18). Mother’s little helper. Newsweek, 51–59.

Heath, C. (1992). The delivery and reception of diagnosis in the general-practice consultation. In P. Drew & J. Heritage (Eds.), Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings (pp. 235–267). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hevey, D. (1992). The creatures time forgot: Photography and disability imagery. London: Routledge.

Hillyer, B. (1995). Feminism and disability. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Instad, B., & Whyte, S. (Eds.). (1995). Disability and culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Johnstone, B. (1990). Stories, community and place: Narratives from middle America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Labov, W. (1972). The transformation of experience in narrative syntax. In W. Labov (Ed.), Language in the inner city (pp. 354–396). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lindenbaum, S., & Lock, M. (Eds.). (1993). Knowledge, power and practice: The anthropology of medicine and everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Maynard, D. (1991a). Interaction and asymmetry in clinical discourse. American Journal of Sociology, 97(2), 448–495.

Maynard, D. (1991b). The perspective-display series and the delivery and receipt of diagnostic news. In D. Boden & D. Zimmerman (Eds.), Talk and social structure (pp. 164–192). Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Maynard, D. (1992). On clinicians’ co-implicating recipients’ perspective in the delivery of diagnostic news. In P. Drew & J. Heritage (Eds.), Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings (pp. 331–358). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mishler, E. (1984). The discourse of medicine. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Morris, G., & Chenail, R. (Eds.). (1995). The talk of the clinic: Exploration in the analysis of medical and therapeutic discourse. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Morris, J. (1991). Pride against prejudice: Transforming attitudes to disability. Philadelphia: New Society.

Murphy, R. (1987). The body silent. New York: Henry Holt.

Nagler, M. (Ed.). (1993). Perspectives on disability (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Health Markets Research.

Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. New York: Free Press.

Phillips, M. (1990). Damaged goods: Oral narratives of the experience of disability in American culture. Social Science and Medicine, 30, 849–857.

Schegloff, E. (1988). On an actual virtual servo-mechanism for guessing bad news: A single case conjecture. Social Problems, 35(4), 442–457.

Schegloff, E. (1992). On talk and its institutional occasions. In P. Drew & J. Heritage (Eds.), Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings (pp. 101–136). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schmidt, D., & Leppik, I. (Eds.). (1988). Compliance in epilepsy. New York: Elsevier.

Shapiro, J. (1993). No pity: People with disabilities forging a new civil rights movement. New York: Times Books.

Shaw, B. (Ed.). (1994). The ragged edge: The disability experience from the pages of the first fifteen years of The Disability Rag. Louisville, KY: Advocado Press.

Silverman, D. (1987). Communication and medical practice: Social relations in the clinic. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Van Maanen, J. (1988). Tales of the field: On writing ethnography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wilson, J., Braunwald, E., Isselbacher, K., Petersdorf, R., Martin, J., Fauci, A., & Root, R. (1991). Harrisons principles of internal medicine (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Zola, I. (1982). Missing pieces: A chronicle of living with a disability. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

1The disability studies literature, which addresses issues in the social experience of disability, is large and growing. In addition to the sources cited in the text of this chapter, references include L. Davis (1995); Ferguson, Ferguson, and Taylor, 1992; Fine and Asch, 1988; Hillyer, 1995; Murphy, 1987; Nagler, 1993; Phillips, 1990; and Zola, 1982. The scholarly journal in this field is Disability Studies Quarterly. Activist literature in disability studies, which addresses issues in the formation of a disability culture, is a growing field as well. Sources include Gallagher, 1990, 1994; Hevey, 1992; J. Morris, 1991; and Shapiro, 1993. Activist newsletters and magazines include The Disability Rag (see the collection edited by Shaw, 1994), This Mouth Has a Brain, and Mainstream. Other areas of academic and popular literature on disability include social histories and memoirs, such as Black, 1996, and Finger, 1991, as well as books of information and advice for patients and families (one of the best of these is Featherstone, 1980).

2Since the conventions of contemporary ethnograpgy require that the investigator reveal his or her situatedness (Clifford & Marcus, 1987; Geertz, 1983; Van Maanen, 1988), I note here that the focus of this project on families who have children with disabilities arises out of my personal experience as the parent of a child with cerebral palsy, making me a situated participant with an extensive background in this population. In the design and analysis of this project, I have chosen not to foreground my own experiences, but I acknowledge that my personal background was crucial in the conception of the project and in my ethnographic access to the institutions and individuals who participated in this research. I would like to thank these many participants who remain anonymous in this work, especially the staff and families of the Child Care Clinic. I also would like to thank the programs at Wayne State University that have provided support for this research, including the College of Urban, Labor, and Metropolitan Affairs, the Humanities Center, and the Career Development Chair program.

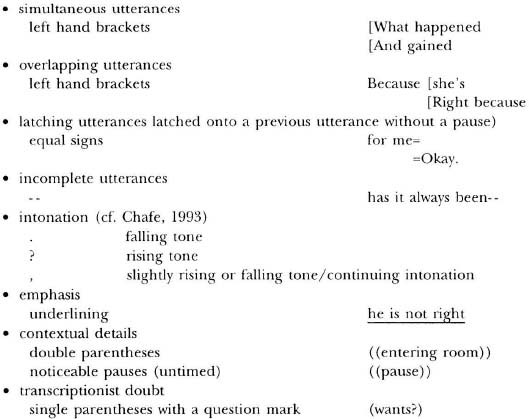

3The broad transcription of these exchanges follow a subset of conventions from Atkinson and Heritage (1984, pp. ix–xvi):

At this time, timing of pauses, lengthening, inhalations/exhalations, and gaze/gesture have not been systematically transcribed. I have used regularized spelling in these transcripts.