CHAPTER ELEVEN

MEASURING AND EVALUATING INNOVATIONS

SENIOR EXECUTIVES IN THE FORD Motor Company were ecstatic when the Edsel was unveiled in 1957. The development and launch of the Edsel had been carefully and skillfully managed, and the executives were confident the car would be a success. Yet as we all know, the car that was to be the key to Ford’s return to a position of power in world auto markets was an immediate market disaster. In many companies, this would be the prelude to finding scapegoats and cutting off heads. Ford’s senior executives did not waste time blaming irrational customers or poor internal performance, however, as these managers were convinced that the Edsel was close to being a perfect car—if the prevailing wisdom in the U.S. auto industry about consumer behavior was correct. So Ford carefully investigated the assumptions it had used about market segments.

What the investigations showed was that the socioeconomic segmentation of the industry (used so effectively by Alfred P. Sloan to market General Motors vehicles some thirty years earlier) was no longer valid. In its place, the researchers found a “lifestyles” form of segmentation, and analysis using the new segmentation method showed that the Edsel’s market failure was predictable and inevitable. The new model showed that the Edsel, positioned between the Mercury and the Lincoln, was really in no “position” at all.

The Edsel remains a famous market failure. But the postintroduction evaluation of the Edsel led to two of the auto industry’s most successful vehicles, the redesigned Thunderbird and its later sibling, the Mustang. Ford learned from its failure. Many do not.

EVALUATING THE

CORPORATE INNOVATION STRATEGY

ALTHOUGH THE EVALUATION of the corporate innovation strategy is not strictly part of the innovation evaluation, the corporate innovation strategy must be reviewed at regular intervals by the senior executive team. If the strategy makes no sense in light of changes in the external and internal environments, then the proposed innovations probably make little or no sense either. As Peter Drucker has noted, there are five basic innovation strategies, which we have condensed to four. You can be:

1.The first to market

2.A rapid follower

3.A niche player, either product or market

4.The one to respond to changing market needs and expectations1

Each requires quite different skills and capabilities, and each implies a unique set of measures of success.

FIRST TO MARKET

Being the first to market requires that the innovator aim at dominating the market, either permanently or until a predetermined level of competitor response has occurred. The innovation needs to be very carefully researched and developed, and the launch must be exploited aggressively. If the innovating company intends to stay in the market, it must invest heavily in order to keep lowering prices and creating greater value in the product. Should the company intend to exit the industry as competitive pressure increases, it must be able to identify the point at which exit is necessary, and it must have the ability to switch resources to the next innovation. Sony’s Walkman is an example of this strategy.

RAPID FOLLOWERS

Rapid followers need not necessarily be excellent at product innovation, although it certainly helps. They do need to be good at process innovation, for the rapid follower needs to be able to drive costs down faster than the market leader. The rapid follower also needs to be able to identify significant market needs that the market leader is not satisfying, and must be able to adapt product designs quickly to exploit these opportunities. This strategy requires that the rapid follower capture significant market share from the market leader in a limited time or be forced to exit the market. Xerox lost significant market share in photocopiers when the Japanese manufacturers launched smaller, less expensive machines for smaller business offices.

NICHE PLAYERS

Niche players specialize in developing special products for general markets or products for specialized markets that the major players identify as being uneconomic. This requires the niche player to be able to develop and produce products cost-effectively at low volumes; exploiting economies of scale is not appropriate. Here are some examples. SAAN department stores of Winnipeg, Manitoba specialized in serving smaller, secondary markets in Canada, markets in which larger, national competitors would not place stores. Irwin Seating of Walker, Michigan specializes in producing theater seating and is the global leader in this niche. Barrday of Cambridge, Ontario specializes in weaving specialty industry textiles, among them: the material for ice hockey skates, and filter material for use in ore-extraction industries.

CHANGING CUSTOMER NEEDS AND EXPECTATIONS

Those innovators who focus on changing customer needs and expectations necessarily aim at increasing the value customers receive from the product package. In effect, these innovators expand the customers’ notion of what the total product package is. Singapore Airlines has been at the forefront of innovation in service offerings and service performance in air travel for over twenty years. The airline consistently ranks at the top of airline performance surveys by business and tourist air travelers. Manufacturers can also change customers’ needs and expectations through service innovations. Japanese automobile manufacturers captured market share in North America in the 1980s in part because their dealers provided service of a higher standard than did the U.S. auto companies’ dealers. Toyota now offers customers in Japan the ability to order a customized car and have it delivered within seven days. All these innovators have one thing in common: an ability to identify latent needs that customers do not realize they need and then “delight” the customers by providing the performance or service need.

Identifying an opportunity is one thing. Being able to exploit the opportunity is quite another. As previously stated, a company must have the innovation-exploiting capabilities in place or available before the concept is approved. And, as we have also noted, the most critical capability is competent management.

EVALUATING INNOVATIONS

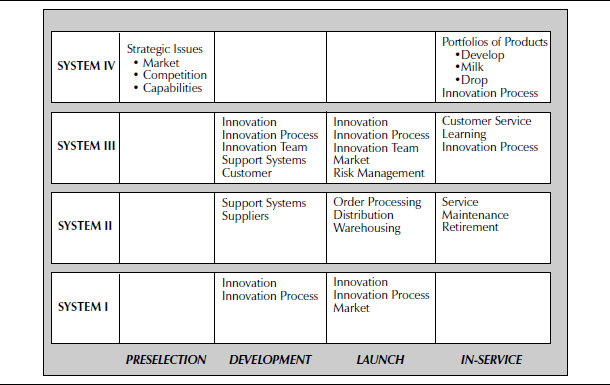

THE EDSEL STORY that opened this chapter has three lessons. First, the clearest (and most important) evaluation of an innovation takes place in the marketplace. Second, innovations need to be evaluated by the marketplace before the innovation is launched. And third, careful and objective evaluation of marketplace performance of all innovations is critical to the longer-run performance of the company. As Figure 11-1 shows, therefore, evaluation takes place at all stages of the innovation management process, and at every level in the system.

Without evaluation, we are guaranteed failure of both the current innovation and future innovations. Knowing that we have to evaluate innovations is one thing, though—actually practicing effective evaluation is quite another. In this chapter, we focus on the evaluation aspects of managing innovation.

Perhaps the most appropriate place to start is with six basic questions: When? What? Why? How? Who? Where? Providing answers to these questions defines an organization’s innovation strategy.

FIGURE 11-1.EVALUATION AT ALL STAGES OF THE INNOVATION MANAGEMENT PROCESS.

ACTIVITY |

EVALUATION FOCUS |

Nurture |

Corporate Values Focus Organization Compensation Communication |

Develop |

Market Segmentation Process Development Resources Recruiting and Developing People Corporate Knowledge Base |

Implement/Commercialize |

Operations Experimenting and Prototyping Process Application Technology Application Distribution Suppliers |

Exploit |

Sales Growth Marketing/Promotion Product Line Extensions Distribution Extensions Financial Return New Capabilities |

WHEN?

Effective evaluation is conducted regularly. We need to evaluate innovations at all stages of their development and use. Appropriate evaluation, early and often, invariably identifies changes that need to be made before the change becomes strategically, operationally, and financially prohibitive. Ford could have identified the market segmentation problem well before the Edsel got to the marketplace. Evaluating too frequently, though, places a heavy burden on those conducting the evaluations and distracts people being evaluated. It is true that we manage what we measure, but overmeasurement leads inevitably to overmanagement and control, not support and guidance. And if the interval between evaluations is too short, there may be no new usable information obtained, which defeats the purpose of the evaluation in the first place.

All managers should remember that the evaluation process forms part of the adaptive feedback loop in the innovating system. When a manager acts on the results of an evaluation, it is as important as when the evaluation is carried out. As a general rule, the person controlling the process under evaluation should make the first corrective moves. Superiors should not intervene until it is clear that the subordinate does not have either the resources or the capacity to make effective corrections. This is as true of mechanical processes as it is of organizational processes. If, as we suggested in earlier chapters, appropriate policies have been established, reasonable managers ought to make reasonable decisions. After all, the most critical capability is effective management, so all efforts should be made to develop effective managers, not to stifle their development.

WHAT?

Customers don’t see all our innovations. Only product and service performance are observable, and then only in the marketplace. Innovations in process technology, organizational innovations, value chain innovations, and innovations in the other categories discussed in Chapter 6 are not directly observed by customers, even if we bring them into our facilities. How should we evaluate innovations before the marketplace sees them—if it sees them at all? Waiting for the marketplace may be too late. This requires us to also understand what to evaluate.

From a strategic point of view, it is important that organizations critically evaluate performance of the development process and the system in which it is embedded. Evaluating the innovation itself is generally fairly straightforward. Evaluating the process and systems aspects of the innovation is considerably more difficult. So we have to understand what aspects of the innovation process and system we need to evaluate, as well as when to do this.

WHY?

Evaluating innovations themselves is critically important. If we limit ourselves to this single purpose, though, we probably shortchange ourselves and ignore valuable information. Why not use our innovations to critically evaluate the process of innovation itself? And why not use our innovations to evaluate our capacity to innovate? We evaluate at different stages for different reasons, but in effect at all times we are evaluating:

•Our innovation strategy

•The market opportunity

•Our ability to exploit the opportunity

•The opportunity for further innovation

•Trends in market needs and demands

•Our innovation performance to date

HOW?

Given the need to evaluate innovations, we need to think about how to do the evaluation. The most important aspect of this is the measurement system we use. The choice of measurement system and its metrics depends in part upon the purpose for innovating, as discussed in Chapter 5. Using an inappropriate set of measures guarantees that we will focus on the wrong issues. In addition to the metrics we develop, though, we need to understand the processes we will use in evaluating, and the tools to be used for this purpose. Metrics for evaluating innovations themselves should be value-based, the bases being time, cost, quality, and service-centered. Metrics for evaluating strategic issues should be (market) performance-based.

There is another important issue under how: How will the evaluations be used? Evaluations should be used to enable the personal and organizational learning process, so that the company becomes better and grows in desired ways. To use the evaluation process to rank people, and to merely punish the guilty and reward the praiseworthy, is shortsighted. As we might imagine, and as we know, the use to which we put evaluations determines how results are reported, and also determines the ways in which the system responds to evaluation. Measurement systems that inculcate fear and finger pointing should have no place in an innovative organization.

WHO?

As in all things, those people with the best knowledge and the greatest ability to effect change—those people in the process being evaluated—should be deeply involved in the evaluation. They should not be the only group, though. Higher-level managers should, where possible, also evaluate process performance (from a strategic point of view), as should disinterested auditors (from technical and operational points of view). It is all too easy for groups to subjectively analyze their own performance. And the group may unwittingly create problems through faulty logic or “groupthink.” Multiple assessments provide a much greater likelihood of objective evaluation and assessment.

WHERE?

The issue of where is more critical in larger, multinational organizations, but it is important in all organizations. Most organizations appear to conduct evaluations where the innovation is being developed. Often, nothing could be less appropriate. Market-focused evaluations should be conducted in critical market locations. Technology evaluations should be conducted where the technologies are being developed. Strategic evaluations should be conducted by the senior executive team. And as we want multiple evaluations anyway, parallel evaluations will likely be conducted in sites removed from the area of interest. The question of what is being evaluated at each stage will need to be understood before the where can be answered.

These issues have to be resolved no matter what innovation or cluster of innovations we are evaluating. Organizations need to develop a process for developing and using market-focused innovation evaluation protocols.

A FRAMEWORK FOR

EVALUATING INNOVATIONS

FIGURE 11-2 IS an outline framework for evaluating innovations. The columns represent the four stages of an innovation’s life cycle:

1.Preselection

2.Development

3.Launch

4.In-service

Each row represents a different aspect of the evaluation processes. Let’s look at the evaluation that occurs in each of the four stages.

EVALUATION IN THE PRESELECTION STAGE

In the preselection stage, we concentrate almost exclusively on the target innovation. We know, as discussed in Chapter 6, that we will probably need to innovate in other areas to ensure real success. These “support” innovations need to be thought through only to the point that their resource needs and the overall innovation timeline can be reasonably established.

We want to emphasize that concept evaluation is strictly strategic. Because it is strategic, it is a System IV evaluation, conducted by the executive team. Their evaluation is best carried out using a decision screen developed specifically for the company (see Chapter 8).2 During this stage, senior managers need to emphasize the internal and external environment, asking questions like:

•What market segment do we want to target?

•What do customers in this segment need?

•What new capabilities will we need?

•How long will it take us to gain access to these capabilities?

•What is the market potential for the development we have just made?

FIGURE 11-2.AN OUTLINE FRAMEWORK FOR EVALUATING INNOVATIONS.

•How long will it take to begin influencing the market segment?

•What assumptions about the industry can we exploit for competitive advantage?

Regardless of the source and type of the primary innovation, senior management has to be satisfied that the innovation or the results of the innovation will create significant value for the target market segment. Further, senior managers have to be satisfied that the investment in the innovation will be handsomely returned to the organization. For products, this should be reasonably straightforward, as discussed in Chapter 5. Innovations in the other sectors (as discussed in Chapter 6), however, require more thought.

These latter innovations must unambiguously demonstrate their strategic value, and their impact in the competitive environment or in the marketplace must be clearly stated. Infrastructure innovations, in particular, have to be critically examined to ensure that they satisfy the strategic criterion. Non-product innovations make sense only if they achieve one or more of the following:

•They increase desired value for customers in the target market segments.

•They reduce internal costs, including transaction costs.

•They improve strategic competencies and capabilities.

•They create new barriers for competitors, perhaps creating sustainable competitive advantage.

Sometimes process innovations are made for the wrong reasons. A division of Dominion Bridge (located in Winnipeg, Manitoba) undertook several process innovations in the late 1980s as part of a major quality management program. These innovations were all suggested by workers and came out of discussions among work teams formed for the purpose. In line with the quality philosophy the division had adopted, any innovation was accepted as being valuable. All the innovations suggested focused on improving conditions for the workers, and most made very modest improvements in process quality. The innovations were all implemented, at some cost to the division, only for the division’s management to discover once the changes had been made that customers saw no added value for them in the new processes.

Toyota’s production system was already mentioned in Chapter 6. The intent of the innovators involved was to develop a production system in which flow through the system would be smooth and predictable. Managers knew that to make this happen, they would need to eliminate all uncertainty in the system, which meant eliminating waste. Waste creates uncertainty, which requires buffers to be placed at strategic intervals. Eliminate the uncertainty, eliminate the buffers—eliminate the buffers, and drive down working capital costs and throughput time in the process. Lower costs translate into a potential selling price advantage. Couple this with a dealer network that customers want to deal with, and vehicles whose maintenance requirements are low, and you create a sustainable competitive advantage.

The developers of the Toyota Production System knew before they began all the years of innovation required to produce the system that the new system would achieve all of the strategic objectives. It is possible to identify strategically significant non-product innovations and to understand what needs to be done in order to achieve the potential success. And it is possible to articulate this, and identify the evaluation metrics, before the executive team approves the project.

In a similar vein, the team that transformed Southwest Airlines’ strategy from a charter operator to a scheduled airline decided to focus on reducing aircraft station time to ten minutes, as a way of keeping the airline flying. Having achieved this feat, and in order to expand past being an airline with only three aircraft and three destinations, Southwest had to ignore the airline industry’s standard “hub-and-spoke” operating philosophy. The company went instead with a series of intersecting “milk runs,” with aircraft arrivals and departures at intersecting airports totally independent of the movement of other aircraft. Breaking the industry assumption that the hub-and-spoke system gave the best operating economies meant Southwest could achieve substantially better economies than any other domestic airline.

To make the milk-run system operate, Southwest had to prove another industry assumption incorrect. Most airline executives believed that the low-fare tourist traffic was unprofitable for regular, scheduled airlines and was best left to charter operators. Southwest demonstrated that the low-fare tourist market segment was large and profitable, because these customers were prepared to accept some routing and time inconvenience in exchange for very low fares. Both Toyota and Southwest Airlines demonstrate that breaking industry paradigms with non-product innovations creates sustainable competitive advantage that can be measured conclusively by improved market performance.

When the executive team considers an innovation proposal, the team rarely considers the proposal solely on its own merits. The executive team is rather concerned with the total portfolio of innovation projects into which the proposal will fit, and what the proposal does to the organization’s risk profile. Many middle managers seem unaware of the risk management role of the executive team and expect their proposals to stand and fall on their own merits. Executive teams might help themselves and their subordinates by taking the time to spell out their risk management strategy and policies and distribute them throughout the organization at regular intervals.

EVALUATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT STAGE

The development stage starts with the executive team’s acceptance of the proposal and the release of resources, and ends with the implementation of the innovation. For a product, this stage ends when production ramps up to target output levels. During the development stage, the emphasis switches to the innovation, the development team and process, and the execution of the innovation by internal and external suppliers. The development stage is a major project in its own right and should take on the characteristics of a project. All development plans should have been presented as part of the project proposal, and both the development team and the innovation should be judged against these plans.

The Focus of Evaluation

What needs to be emphasized here is that we are not simply evaluating the innovation for its own sake during the development stage. What we are really focusing on evaluating are:

•THE INNOVATION STRATEGY AND PROCESS. Are we using an effective and appropriate process?

•THE DEVELOPMENT TEAM. Do we have effective management in place? Are the organizational structures appropriate?

•SUPPLIERS. Do we have effective suppliers who form part of an effective extended team?

•CUSTOMERS. Do we have effective customers who form part of an effective extended team?

•PARALLEL POSSIBILITIES. If we are assessing different approaches to the realization of the innovation, is it clear when we should be shifting resources from one approach to another that is more promising?

•CAPABILITIES. Do we have the capabilities or knowledge necessary to execute the project? Are these capabilities being used appropriately? Do we need capabilities or knowledge of which we were not aware at the beginning? Do we have sufficient resources to complete the project as scheduled?

As previously discussed, every process has suppliers and customers. This is true of the development process for innovations of all types, although the suppliers and customers for most types of innovation are inside the organization. Innovations help people in a system improve their performance. If we cannot identify this group of people (customers) for an innovation, then we better not be thinking about investing resources to develop the innovation.

Reviewing Variances from Plan

These are all performance evaluations; we make evaluations based on prior assessments of resource needs and expectations. So one other important subject for review is the effectiveness of the forecasts and plans we make before the project begins. As we are all aware, too many projects that appear to have come off the rails are actually performing respectably. It is the expectations and forecasts of performance that are poor.

Even though evaluating the external environment is not as important as evaluating the areas above, it should still be undertaken on a regular basis. This allows senior management to be assured that the innovation will still meet market needs. Tweaking an innovation early in its development process is easier and less expensive than making major changes just before launch.

Invariably, the project will be judged using time, cost, quality, and performance metrics. Where variances from the plan occur, managers should be at pains to determine whether the initial plan was overly optimistic, or whether development performance is lower than acceptable. This is often hard to determine, and generally the approved plan is deemed to be achievable. Perhaps the only satisfactory way in which to make this equitable is for the people proposing the project to be placed in charge of its development and implementation.

The development plan might itself contain many stages. There may be a need to experiment with alternative methods of achieving a certain outcome or to build prototypes and conduct tests of service innovations before they are ready for a full-scale launch. The development plan must contain the schedule of experiments and prototyping activities, and the objectives of each experiment or prototype, together with the criteria by which the activity will be judged. Failure to establish the evaluation criteria before conducting the experiment can easily result in the standards being set to achieve the outcome desired by the experimenters. But teams need to be ready to encounter surprises and be prepared for changes even at late stages of the development process.

When McDonald’s launched its pizza nationwide in Canada, the development plan called for test marketing of the product in Ottawa and Winnipeg. The tests proved the product would be a profitable venture and confirmed general predictions of sales volumes and sales trajectories over the launch period and beyond. One uncomfortable surprise for McDonald’s and Martin-Brower, its logistics supplier, was the tendency for restaurant managers to hoard pizza components. This tendency to protect against stocking out was understandable, but hoarding by managers during the national rollout would guarantee shortages of pepperoni and pizza crusts in the second and third weeks of the eight-week launch period. When this hoarding was discovered, the logistics plan was changed to ensure that inventories were centrally managed during the critical period, reverting to restaurant-initiated resupply at the end of the launch period. The positioning of two weeks of anticipated pizza requirements in each restaurant immediately prior to the launch placated restaurant managers and owners, and left sufficient inventory in distribution centers and with suppliers to cover foreseen demand variability across the country’s restaurants.

Reviewing Innovation Performance

The last reason for evaluating an innovation during development is to evaluate overall innovation performance to date. We need to evaluate performance for two distinct reasons. First, we need to make choices among alternative approaches to an innovation, and second, we need to learn how to better manage our innovation portfolio and the process of innovation.

The newer and more radical an innovation, the less certain we are about the best approach to take when developing the innovation. This is particularly true of knowledge innovations. Two other constraints on knowledge innovations are also important. If we don’t get the knowledge innovation right, we will not get a second chance, and time to market is critical.

It is important therefore to adopt the “rule of three” when dealing with leaps where the objective is known, but the means of achieving the objective are unclear. This rule requires three different approaches to the problem to be undertaken, if possible, which means the resources required for each approach have to be allocated. Each group will start work on their approach to the objective, working independently of the other team or teams. Performance of each approach will be frequently assessed, as we need to identify both the most appropriate approach and low-probability approaches as quickly as possible. People and other resources should be transferred from lesser to more promising approaches as our knowledge of what is going to be most appropriate becomes clearer. Ultimately, all the resources from the less appropriate approaches should be assigned to the most promising approach; it is important for momentum and morale to reinforce success.

Evaluating Teams and Trends

Although the development stage is the most complex of the four stages of an innovation’s life cycle, and is the stage that consumes the most resources, evaluation here is reasonably straightforward. The development teams in System I should evaluate themselves and subordinates at frequent intervals. Higher-level managers in System III should also evaluate teams at less frequent intervals, but certainly at milestones and critical points of the development plan. Evaluation should be carried out with a view to improving team performance, not for assigning blame. If team members are looking over their shoulders, focusing on how they will make sure they aren’t blamed for anything, their time is being wasted.

Technical evaluation of the innovation itself should take place continually throughout the development process. The technical people involved in the development in System I should conduct the evaluations, but the evaluations need to be audited in System III. The testing protocols and testing timetable should be established before the development stage begins. One of the most critical repetitive technical evaluations concerns market needs and demands related to the innovation. As we know, market needs and demands are a moving target. The longer the time between concept selection and market impact, therefore, the further the market’s needs and demands will have moved. It is possible to project where the market will be, given observed trends. However, these trends need to be checked at frequent intervals.

EVALUATION IN THE LAUNCH STAGE

Emphasis in the launch stage focuses on the innovation itself, market response, competitor response, and the development team. We will have projections of impact in the marketplace at various times after launch, and we need to evaluate the actual results to understand why the differences occur and what their implications are. Immediate market feedback allows adjustments to be made and may allow early follow-up on unexpected success. We will also have our first major tests of the innovation in use, in both expected and unexpected use modes.

It is immediate competitor response that is the most difficult to combat unless companies are prepared, as deliberate response requires the investment of capital and other resources in a planned approach to regaining lost ground. When we expect no or muted competitive response, this can be a telling time, because we would have to develop plans to stop our launch being stalled. Palm Corporation responded immediately when Microsoft launched its new handheld device to compete with Palm’s own, and as of early 2001, Palm appears to have effectively stalled Microsoft’s entry into the handheld market.

If the development team in System III retains responsibility for the innovation after launch and until the project is through the growth stage on its life cycle, then the development team should continue to be evaluated. If the development team has handed the innovation over to others, this is a good time to do a detailed evaluation of the performance of the development team and the development process, and to make adjustments to the process as necessary.

During a product launch, the initial focus in Systems I, II, and III is on the ramp-up to full-scale production, pipeline filling and other distribution activities, distributor training, rollout of the marketing campaigns, and the implementation of support innovations. Following the launch itself, though, the focus in Systems I and III shifts to the marketplace and evaluation of sales penetration. It is at this point that the organization needs to be flexible, for market response is unlikely to be exactly to plan. The flexibility should be built into the risk management plan for the launch, and emergency management plans should be developed for the most likely scenarios and the scenarios with the greatest associated loss severity. If this is not done, what should have been an emergency can easily become a crisis, with attendant business risk.

When McDonald’s launched its pizza in Canada, national sales figures were right in line with projections at the end of the second day of sales. Unfortunately, what looked good at a national level looked less rosy at a regional level. Sales in Canada’s Maritime Provinces, for example, were considerably below forecast, while in British Columbia sales were running at twice the projected levels. Only a major effort by Martin-Brower to pick up and transport inventories from Eastern Canada to the West, and to divert all shipments from pizza crust suppliers in the United States to British Columbia, saved Vancouver restaurants from not being able to supply their customers. Building flexibility into logistics and transportation plans allowed a crisis to be averted.

Every group involved in the launch should be monitoring and evaluating the detailed technical aspects of implementation, but the development team itself should monitor key performance factors. These factors are the critical items around which the launch risk management plan has been based. Monitoring must be continual, as responses to opportunities and challenges may need to be made quickly.

Organizational innovations pose a particular challenge for evaluation. All infrastructural innovations rely on people for their implementation and effectiveness, and the impact is often difficult to judge early in the process. Attitude surveys may be the most appropriate instrument for gathering data reflecting on acceptance of the innovation, but the surveys should be conducted by skilled researchers and interpreted by people outside the organization.

EVALUATION IN THE IN-SERVICE STAGE

In this last stage of the innovation life cycle, emphasis in System IV switches from evaluating the innovation by itself to evaluating the innovation as part of a cluster of innovations. Clustering takes several forms:

•FAMILY. This involves evaluating the performance of a family of innovations, with a view to making changes based on market trends.

•NUCLEUS. This means evaluating the innovation as the potential seed for a range of specialized innovations in close proximity to the initial innovation. This requires identifying where the better opportunities lie for repositioned innovations.

•SUCCESS. This involves clustering innovations that have met expectations separately from those innovations that have exceeded expectations, and from those that have failed to meet expectations. We want to identify underlying patterns and then try to develop an understanding of why the patterns exist. From there, we should be able to develop effective plans for exploiting unexpected advantage and for eliminating or minimizing unexpected disadvantage.

Evaluating the Innovation System

In addition to evaluating the innovations by cluster, we need to evaluate the ongoing business of innovation. This should be a periodic strategic evaluation of the company and its performance against longer-run competitive measures, and will be a System IV responsibility. It is also an evaluation of our performance in our industry, in particular in the segment of the industry in which we have chosen to compete.

In the in-service stage of the innovation life cycle, it is important that we analyze the longer-run market response to the innovation. This is true of all the innovation forms for, as we have noted earlier, there has to be a market justification for every innovation we undertake. For product innovations, we need to analyze market response to identify whether or not our development process was effective. Products that do not create desired value for the target market segment have not been effectively developed, and management has to understand where the problem occurred in order to improve the development process.

Companies also need to analyze market response to determine what further innovation opportunities exist. Sony has demonstrated the effectiveness of exploiting the “space” close to the original innovation with its brilliant management of the Walkman series of portable players. Exploiting the space close to the original product makes sense for a number of reasons:

•Market opportunities are more easily assessed when potential customers have good to very good knowledge of the product.

•The company has in-house or available all or almost all the capabilities required to develop and launch the new innovation, as these capabilities would have been required during the development of the original innovation.

•The experience gained from the first innovation provides more appropriate measures and measurement systems than were used for the original innovation.

•Senior management is better able to make the necessary strategic decisions for the “exploiter” innovations than was possible for the original innovation.

Perhaps the most important reason for reviewing innovations in-service, though, is to review the portfolio of products the organization offers its target market segments. The review at the highest levels of the organization might be conducted only every three years or so, and may focus on only the most significant products. This review can identify products that should be removed from the portfolio, products that need to be repositioned, and areas in which new innovations seem to be needed. Such a review can also explicitly evaluate overall innovation performance, benchmarked against competitors, to identify any major changes that might need to be carried out in the innovation process.

INNOVATIONS IN EVALUATION

MOST MANAGEMENT EVALUATION methods are based on the mechanical model of the world. They evaluate discrete parts, not the whole. This flies in the face of our systems view. Others have recognized this. For example, financial services companies have begun incorporating intangible elements such as service quality into their formerly quantitative, short-term–focused measurement systems.3 This involves developing a more balanced approach to evaluation and changes in measurement metrics. Many banks now conduct regular surveys of customer satisfaction, and use the results in evaluating branch performance. One health insurer, National Mutual of Canada, now allows corporate customers to claim premium rebates if service performance is deemed to be below expectations. Standard Life, Canada’s oldest life insurance company and part of the Standard Life Group of Edinburgh, Scotland, has melded two such approaches, the Balanced Scorecard4 and a model based on the European Foundation for Quality Management’s self-assessment criteria.5

The Balanced Scorecard is based on the assumption that focusing on one set of measures causes strategic and operational drift and a loss of relevance and competitiveness. The four clusters or dimensions of the original Balanced Scorecard are financial, customer, internal business processes, and learning and growth. By deciding on what specific drivers of performance are important in moving the organization toward its strategic goals, managers can develop measures that capture performance in each area. Using a balanced set of measures shows when the train starts to drift off the rails, and corrective measures can be applied. The Balanced Scorecard is indeed part of a strategic management system.

We can, and should, use several performance indicators for each dimension. The innovative company might use some of the following indicators:

FINANCIAL DIMENSION

•Return on innovation investment

•Market share

•Cost savings

•Total project cost

CUSTOMER DIMENSION

•Use of lead users in development

•Customer satisfaction

•New customer attraction rates

INTERNAL BUSINESS PROCESSES DIMENSION

•Overall development team performance

•Development cycle time

•Number of prototyping cycles

•Total project personnel hours

LEARNING AND GROWTH DIMENSION

•New skills introduced to the company

•New core technologies developed

•Number of new project team leaders identified

•Average hours of employee training investment

An innovative company can use the Balanced Scorecard to evaluate individual innovations, clusters of innovations, or the complete product portfolio. However, the Balanced Scorecard’s measures need to be augmented if the benefits of innovating are to be effectively captured. One way of doing this is to capture what has been called the innovation premium.6 This allows companies to calculate the financial returns that accrue from creating new value. The innovation premium can then be used as a key financial indicator in the Balanced Scorecard.

The dimensions of the innovation premium relate to the principal stakeholders in the company, and are:

•Owners—The Best Company in which to Invest

•Customers—The Brand to Buy

•Employees—A Great Place to Work

•Partners—Preferred Partner to Have

The innovation premium is important. Using the Balanced Scorecard in concert with the innovation premium is also important, for it is possible to subvert even the innovation premium for short-term gain, and resultant long-term pain. In all our endeavors, we want to ensure that we have a vital and dynamic system. Concentrating on the innovation premium alone might be analogous to a bodybuilder using steroids, with the same sorts of long-term issues for the body corporate.

SUMMARY

•Evaluation of innovations should be market-based where possible. This applies to both product and non-product innovations.

•The level at which evaluation is done moves from strategic at the concept stage through operational and tactical in the development stage, tactical in the launch stage, and back to strategic in the in-service stage of the innovation life cycle.

•While we are always evaluating the innovation, the focus is often on the process represented by the innovation. This is analogous to the use of product samples in statistical process control (SPC) to understand and improve the operating process.

•The corporate innovation strategy itself needs to be evaluated at regular intervals and when marked changes occur in the environments affecting the company. The only test for the corporate innovation strategy is effective support of the corporate strategy.

•The evaluation protocols must be developed as part of the innovation proposal. The protocols should answer the six basic questions: When? What? Why? How? Who? Where?

•Use of the Balanced Scorecard and an understanding of the innovation premium can be helpful in evaluating the innovative company. All the measures should support those used at higher levels in the organization.

NOTES

1. Peter Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship (New York: Harper Business, 1993).

2. Roger Bean and Russell Radford, Powerful Products: Strategic Management of Successful New Product Development (New York: AMACOM, 2000).

3. “Survey—Mastering Management,” Financial Times, October 16, 2000.

4. Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton, “Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management Tool,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 1996.

5. Caroline Goulian and Alexander Mersereau, “Performance Measurement: Implementing a Corporate Scorecard,” Ivey Business Journal, September-October 2000.

6. Ronald S. Jonash and Tom Sommerlatte, “The Innovation Premium: Capturing the Value of Creativity,” Prism, Third Quarter 1999.