CHAPTER 3

Business Continuity Best Practices

COMPANIES THAT ARE fully aware of business continuity have applied a best practice business continuity planning process to develop a mature program that both aligns with current standards and is tailored to address operational risks and meet the needs of the organization and its stakeholders.

Included in this chapter is one approach to current business continuity best practices. This approach reflects the latest iteration of the methodology I have successfully used over the past twenty years in working with a broad range of businesses and organizations. Over time, accepted best practices have changed to meet the evolving scope and requirements of business continuity planning, and they will continue to change as business continuity further matures as a business practice.

It is important to keep in mind that business continuity planning is neither a one-size-fits-all blueprint nor is it an all-or-nothing proposition. Instead, it is more of a spectrum of readiness. Requirements and standards vary among industries. Continuity strategies that work for one company can result in absolute failure for another. An event that is a disaster for one company can be an insignificant inconvenience for another. Following accepted business continuity best practices to the letter may not always be the best approach for every organization. Doing so may simply not be feasible for some companies because of time or money constraints or lack of full executive level commitment. Best practices are most effective when they are applied in combination with real-world common sense, intelligence, and innovation, while always keeping in mind the company’s culture, situation, and requirements.

Developing a Business Continuity Program

While a plan is a necessity to codify and document the business continuity program as well as to provide guidance for implementing continuity strategies, a comprehensive program must go well beyond what to do after a disaster occurs. A business continuity program must incorporate these four components:

1. Hazard assessment and mitigation

2. Preparedness

3. Response

4. Recovery/continuity

Simply put, the plan is the operator’s manual for the program, and as such it must both provide detailed procedures for carrying out continuity strategies and outline requirements for training, testing, and program maintenance.

A hazard assessment—the first component of the business continuity program—identifies and quantifies the threats and risks to a business in a specific location. Mitigation involves the planning and actions taken to eliminate those threats and risks to the extent possible prior to their occurrence. This could, for example, include installing electric power generators or arranging for leased generators before a power outage occurs. When the risks identified cannot be eliminated, mitigation involves the planning and actions taken in advance of a destructive or disruptive event in order to reduce, avoid, or protect against its impact—for instance, installing security systems and limiting building access to eliminate or control unauthorized access to facilities to avoid sabotage, theft, and vandalism. For the supply chain specifically, replacing a critical supplier identified as being at risk would be an example of a mitigation measure to eliminate a risk. Having a redundant (backup or alternate) source for the product or service provided by a potentially at-risk supplier is a measure to protect against impacts should the supplier go out of business. Based on a cost-benefit analysis, the selected mitigation steps must be cost-effective and must provide safeguards against one or more hazards.

The second component of the program, preparedness, includes all actions taken before a destructive or disruptive event occurs in order to lessen its impacts on the organization and its operations. This encompasses writing and testing plans, organizing and training teams to carry out those plans, and stocking and maintaining emergency supplies and equipment. For the supply chain, maintaining complete and current contact lists of all suppliers, contractors, transport companies, and others crucial to continued supply chain operations, as well as having off-site access to those lists, are valuable preparedness steps. Both mitigation and preparedness must be ongoing to meet an organization’s changing needs, operations, financial situation, technology, competitive market, regulatory requirements, and industry conditions.

The actual response to a destructive or disruptive event— the third component of the program—often begins while the event is still occurring. This could include evacuating the building, accounting for employees and visitors, and obtaining necessary medical attention. For the supply chain, a response action could involve shutting down warehouse equipment before an evacuation. Also part of the response phase is the initial assessment of damage as well as actions taken to prevent further damage.

The final component of the program, recovery/continuity, may begin either before or immediately after the response phase is concluded, depending on the type of disaster, and would include any actions taken to work toward a normalization of operations in accordance with the priorities established and documented in the business continuity plan. This could include conducting an in-depth assessment of damage and operational impacts, notifying employees when to return to work, relocating operations and employees, or responding to media requests for information. A supply chain–specific continuity action could include establishing and maintaining contact with suppliers, customers, and carriers.

Each business unit is a unique operation and needs to be involved in the development and maintenance of the organization’s business continuity program. A planning process that incorporates all levels of the company results in a continuity capability that both protects the organization and may serve as a competitive advantage.

To ensure the continued success of a business continuity program, it is essential that ongoing ownership and oversight of the program be specified in the plan and assigned to a position that reports directly to senior management. Such guidance and direction for a successful program is ensured through corporate-level planning standards and policies. Management’s active commitment to the project and resulting business continuity program will provide support for the planning process and make available the required resources.

The Business Continuity Planning Process

While business continuity programs are ongoing, the initial planning process is a project with a specific objective, a defined start and end date, and, more often than not, limited resources.

Business continuity planning should be approached as you would any other project. A strong project manager ensures that the project stays on track regardless of its focus. Typically, a planning group—whether a team, task force, or committee—is involved, with its members working together to achieve a common goal, which is the development and implementation of a comprehensive continuity program. This team approach is valuable for several reasons. First and foremost, business continuity is enterprise-wide. Representation from all key departments provides a more inclusive perspective and an accurate understanding of the organization and its operations. The program then becomes one in which all business units have ownership. While this is not the primary rationale for having a planning team, this approach results in a sharing of the work involved. Once the team is established, using project management best practices helps steer the group through the continuity planning process.

Time invested at project initiation is well spent and pays dividends over the course of the project. This includes establishing the project process, scope, goals, and deliverables and identifying all participants: the executive sponsor, the individual responsible for review and approval, the planning group leader, group members, and go-to people for special requirements such as advice on legal issues. It also includes establishing the project schedule with a timeline, milestones, and a monitoring and reporting process.

Great assets that planning group members can bring to the project include the abilities to think critically, strategically, and creatively. The involvement of people throughout the organization with a certain level of understanding of continuity planning principles and process is necessary as well, to ensure that those assigned to the project have sufficient know-how to successfully complete the work required. This may necessitate some training, whether it’s through reading books, taking formal classes, or attending workshops and seminars. Another approach is to have training presented in-house for the entire planning group.

Using a Consultant

In some cases, contracting with a consultant may be an advantageous solution to narrowing a knowledge and experience gap or to providing person-hours that employees do not have to dedicate to the project. The project plan should be reviewed in detail to determine when working with a consultant would be beneficial. This may be if outside assistance would be beneficial for the entire project, to facilitate the planning process, or only for certain project phases and tasks. You should also identify where in the scope of the project it is necessary to get a consultant’s expertise, experience, guidance and direction, and unbiased perspective on the organization and its operations. It may be determined that a consultant is needed to facilitate the planning process, conduct the business impact analysis (BIA), or assist with the development of plan documents, or it may be determined that hands-on assistance is needed with each task of each project. If it is decided that hiring a consultant would be a good investment, the following tips can be helpful:

![]() Make sure that the consultant won’t recommend solutions or strategies that require purchasing products and services that the consultant provides or represents.

Make sure that the consultant won’t recommend solutions or strategies that require purchasing products and services that the consultant provides or represents.

![]() Avoid a situation where methodologies, documents, or other deliverables remain the property of the consultant rather than your organization.

Avoid a situation where methodologies, documents, or other deliverables remain the property of the consultant rather than your organization.

![]() Insist on a learn-as-you-go approach that results in a knowledge transfer at every step of the project. This helps your organization develop an internal capacity to maintain, update, and further enhance its business continuity capabilities without the need for the consultant to return year after year.

Insist on a learn-as-you-go approach that results in a knowledge transfer at every step of the project. This helps your organization develop an internal capacity to maintain, update, and further enhance its business continuity capabilities without the need for the consultant to return year after year.

Using Software

Another consideration may be the use of a software package that automates many elements of the planning process, such as conducting a BIA. The number of new vendors and software packages skyrocketed after 9/11 and has continued to grow as business continuity is increasingly recognized as a fundamental element of good business management. Using one of these tools may be helpful in your planning process—with some caveats.

Software should not be allowed to drive the project. It is important to remember that software is a tool; it does not do the work. People do the work. Software does not gather the information needed for the BIA. In addition, various steps require a human component. These include following up with those who are less than timely in providing input, validating questionable responses to surveys, and getting more detailed information. Computers cannot develop insight as a result of life experience. People know their organization’s operating environment, culture, and people—all key considerations when developing a business continuity program. Computers have no IQ, have no emotional intelligence competencies such as teamwork, collaboration, initiative, empathy, or motivation, and lack spontaneous interactivity capacity. Common sense, good judgment, and the mysterious process of intuition can be indispensable in finding and selecting the most appropriate continuity strategies.

While some software packages are more user-friendly than others, there is a learning curve for any new software. Providing training to the people who will be using it is critical, and this involves building training time into the project schedule. Without training, users will be slower in operating the software, make more errors, possibly become frustrated, and in a worst case doom the successful use of the software.

If, after analyzing the ins and outs of using a software package, the decision is to continue to investigate the possibilities, the real work begins as you prepare to select the best software for your organization. A selection committee should be established made up of representatives of all those who will be using the software, including the individual heading the project as well as team members and someone from your IT department with experience in evaluating software. An initial investigation of vendors and their software should be conducted by reviewing printed material and online information. Most software vendors are pleased to have an opportunity to provide a demo, which selection committee members can try out to get an initial impression of the product’s capabilities and usability.

As a final check before a decision is made to purchase a software package, a cost-benefit analysis should be conducted to determine whether this is the best use of project dollars. This should include the following questions:

![]() Does the software short-circuit the planning process, which can be equally as beneficial as the written plan?

Does the software short-circuit the planning process, which can be equally as beneficial as the written plan?

![]() Is there equal value from a computer-based BIA as with one conducted without the software?

Is there equal value from a computer-based BIA as with one conducted without the software?

![]() Does the process still involve key people from all the business units?

Does the process still involve key people from all the business units?

![]() Can you get a better return on the same amount of money by, for example, adding a full-time position or hiring a consultant?

Can you get a better return on the same amount of money by, for example, adding a full-time position or hiring a consultant?

After applying the criteria agreed upon at the beginning of the process, all vendors can be evaluated and your choice narrowed down to three to five. The finalists can then be invited to an interview where they have an opportunity to demonstrate the product, respond to questions and concerns, and discuss pricing. All costs, fees, and expense items—such as licensing fees, implementation assistance, initial and follow-up training, upgrades and enhancements, and support services—should be identified.

Work with the procurement department throughout the selection process to ensure that all company purchasing policies and procedures are being followed. Once a final selection has been made, procurement can assist with negotiating a contract that includes a detailed list of deliverables, warranties, and service level agreements and facilitate the contract approval process.

I am amazed when I listen to people from two organizations who are talking about software packages their companies purchased. One individual praises his company’s package, while the other derides her company’s package. Then I learn that they are talking about the same product. There are companies that have purchased such software but have not used it for anything except, perhaps, as a very expensive doorstop. There are any number of reasons for this, including a failure to select a package that is the best fit for the company, unrealistic expectations about what the software can do, or a belief that the software will replace the need for people to be involved in the project.

A well-chosen software package can be an excellent tool to assist in conducting the BIA or other project tasks. But whether or not you opt to use software, it is the people involved in the project—their intelligence, knowledge of the organization, creativity, and blood, sweat, and tears—that ultimately determine the success of your BIA and the resulting business continuity program.

Beginning the Project

In preparation to begin the project:

![]() Determine exactly what is currently in place and what must be developed.

Determine exactly what is currently in place and what must be developed.

![]() Gather necessary documents such as any existing business continuity or related plans like emergency response plans, security plans, and company policies that relate to the upcoming project.

Gather necessary documents such as any existing business continuity or related plans like emergency response plans, security plans, and company policies that relate to the upcoming project.

![]() Identify all regulatory, legal, and industry business continuity requirements.

Identify all regulatory, legal, and industry business continuity requirements.

![]() Confer with the person who manages the company’s insurance program to gain an understanding of current coverage.

Confer with the person who manages the company’s insurance program to gain an understanding of current coverage.

Despite the application of best business continuity and project management practices, continuity planning can still fail. To help ensure a successful end product and an optimum outcome, lay the groundwork at the beginning of the project:

![]() Establish the project’s scope and a realistic and attainable project schedule. This avoids misunderstandings about what will and will not be accomplished and avoids having to take dangerous shortcuts in order to meet an unrealistic timeline.

Establish the project’s scope and a realistic and attainable project schedule. This avoids misunderstandings about what will and will not be accomplished and avoids having to take dangerous shortcuts in order to meet an unrealistic timeline.

![]() Ensure that sufficient resources are dedicated to the project, including project team members with the necessary skills and knowledge and a budget that covers all reasonable expenses associated with the planning process. This avoids having to ask for additional resources, which can delay or derail the project.

Ensure that sufficient resources are dedicated to the project, including project team members with the necessary skills and knowledge and a budget that covers all reasonable expenses associated with the planning process. This avoids having to ask for additional resources, which can delay or derail the project.

![]() Kick off the project with an announcement made by the project’s executive sponsor or senior-level executive. Evidence of top management’s support validates the project and encourages participation.

Kick off the project with an announcement made by the project’s executive sponsor or senior-level executive. Evidence of top management’s support validates the project and encourages participation.

![]() From the start, communicate the business continuity project throughout the organization to ensure that all managers and other employees understand the project, its purpose, its impacts, and what is expected of them. Doing so encourages cooperation and prevents rumors and misinformation.

From the start, communicate the business continuity project throughout the organization to ensure that all managers and other employees understand the project, its purpose, its impacts, and what is expected of them. Doing so encourages cooperation and prevents rumors and misinformation.

At the launch of a business continuity project, there are two known factors that are the initial focal point of the planning process: (1) the organization as it exists and (2) the risks that currently pose a potential threat to the organization and its operations. From there, an effective comprehensive continuity planning process enters the assessment phase, which includes understanding current capabilities, conducting a hazard assessment, and conducting a BIA. These best practice activities are the foundation of the continuity planning process.

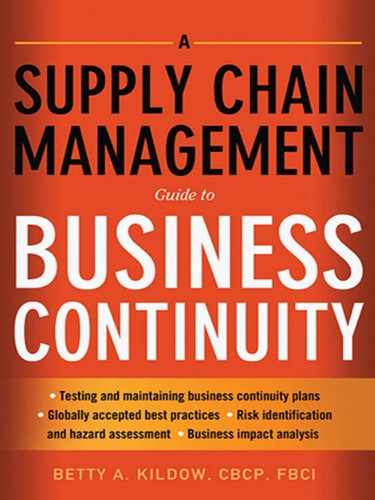

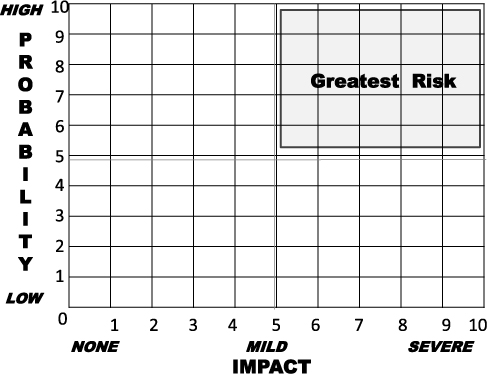

Figure 3-1 represents the business continuity planning lifecycle, an ongoing process of continuity planning that includes the development, maintenance, and testing of business continuity plans to ensure a continually maintained and enhanced business continuity capability. The ongoing lifecycle starts with a hazard assessment and mitigation and then continues through the BIA, development of business continuity strategies, development of business continuity plans and procedures, and the testing and implementation of the plans.

Note that the steps in the planning lifecycle are not numbered. Business continuity planning is not a first step to last step, check-the-box undertaking. Once the initial program is developed, there must be an ongoing process to continually maintain and increase disaster management capability through ongoing review and revision in order to further develop a sustainable, mature program. Without assigned responsibility for maintaining the program and fostering continuity awareness throughout the organization, even blue ribbon programs ultimately fail.

The hazard assessment and BIA are the analysis stage of the project. They serve as the basis for developing the strategies that will be documented in business continuity plans and detailed procedures.

FIGURE 3-1.

BUSINESS CONTINUITY PLANNING LIFECYCLE.

Hazard Assessment

The purpose of the hazard assessment is to gain an understanding of the disasters for which the organization must plan and to establish what level of risk the organization can accept. Conducting this assessment involves three steps:

1. Identifying the organization’s threats and vulnerabilities. What can go wrong?

2. Analyzing the identified vulnerabilities. What is the likelihood it will go wrong?

3. Assessing the resulting impact. What are the consequences if it goes wrong?

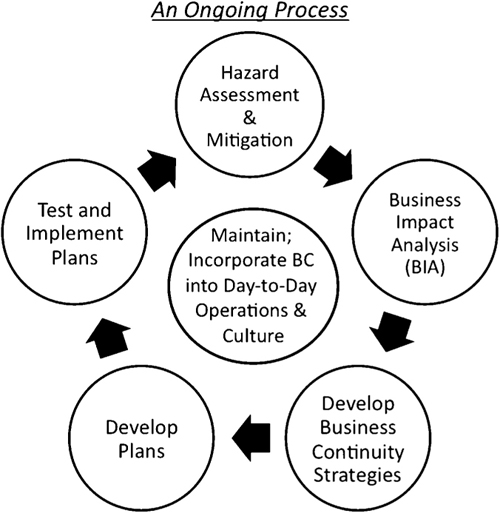

This process requires making some assumptions and doing some forecasting. As a result, it is a certainty that your assumptions will be less than 100 percent accurate, and they may be off by as much as 10 to 20 percent or more. While not perfect, the hazard assessment does produce an increased understanding of the threats to the company and the impact of those threats to critical operations. Based on the results of the hazard assessment, identified risks are mitigated to the extent both possible and practical. Conducting a hazard assessment can be complex, time-consuming, and expensive. However, it is an essential component of the planning process. Figure 3-2 can be a useful tool for identifying the hazards for which mitigation and planning are most needed.

The first step is listing all known hazards and risks. Then, each of the risks should be graphed by two factors:

1. On a scale of 0 (low) to 10 (high), how probable is it that the disaster will occur? (This probability is graphed along the y axis.)

2. On a scale of 0 (none) to 10 (severe), should it occur, what will be the impact of the disaster on the organization and its operations? (This impact is graphed along the x axis.)

Hazards in the upper right quadrant are those that are both most likely to occur and result in the most severe damage, making them the greatest risks to the organization. These hazards are the initial focus of mitigation and planning.

Conversely, the hazards in the lower left quadrant are the least likely to occur and are not likely to result in significant damage or operation disruption. Managing these low-risk hazards can be delayed and in the interim may be resolved by the planning and mitigation done for the hazards that pose the greatest risk.

FIGURE 3-2.

HAZARD ASSESSMENT GRAPH.

Business Impact Analysis

The business impact analysis is a process used to identify mission-critical business functions, which may also be referred to as time-critical business functions. The BIA identifies the internal and external dependencies of each of the identified functions, establishes a priority order in which to restore them, identifies resources needed for each of these functions (such as facilities, personnel, equipment, electronic data, paper records, and software), and develops a target time frame for the full restoration of each. The results of the BIA are used as a basis for developing business continuity strategies.

Some of the BIA deliverables have value-added benefits above and beyond their use in continuity planning. Documented processes, detailed descriptions of individual business functions, identification of interdependencies, and process flow charts that are developed in the BIA process are all useful well beyond the business continuity planning process.

Strategy Development

Business continuity strategies are developed to support the results of the impact analysis. Because formulating continuity strategies tackles need-to-survive rather than business-as-normal challenges, a different mindset is necessary. Developing strategies needed to resume or maintain all identified critical business functions and processes can be daunting. An uncomplicated way to begin is by starting with the functions identified in the BIA results as most critical, and then for each, identifying how to ensure backups or substitutes for:

![]() People Who Carry Out the Identified Critical Functions. Who can step in if the people who have primary responsibility for these functions are not available?

People Who Carry Out the Identified Critical Functions. Who can step in if the people who have primary responsibility for these functions are not available?

![]() Facilities Where the Critical Functions Take Place. Where can they be relocated if the primary facility is lost or inaccessible?

Facilities Where the Critical Functions Take Place. Where can they be relocated if the primary facility is lost or inaccessible?

![]() Critical Business Processes. Is there a temporary substitute if the primary process is unavailable, or can one be quickly established?

Critical Business Processes. Is there a temporary substitute if the primary process is unavailable, or can one be quickly established?

Plan Development

Successful business continuity efforts result from an analysis of possible situations and the development and proper testing and execution of plans and procedures. Business continuity plans are written to document the program and its strategies and then serve as its operations manual.

As a result of an ever changing environment, constantly evolving technology, unforeseen circumstances and events, and other variables, plans will not always be 100 percent spot-on as developed. They are, however, the key to a greatly increased probability for the more rapid and successful continuity of business operations following a disaster.

A business continuity plan formalizes and codifies continuity policies and standards. At a minimum, the plan documents:

![]() What needs to be done

What needs to be done

![]() How it will be done

How it will be done

![]() Where it will be done

Where it will be done

![]() When it will be done

When it will be done

![]() Who will do it

Who will do it

While there are standards and best practices in developing plan documents, each plan must be developed specifically for the organization. One size does not fit all. Taking another organization’s plan or a plan template and simply changing names, contact information, and locations is a recipe for failure; it will not work and will likely create additional problems beyond the initial disaster.

If the organization is of substantial size or complexity, has multiple locations, or is a global or multinational company, more than one plan may be needed. Fully meeting the company’s business continuity needs requires a coordinated “family of plans” starting at the top level of the organization:

![]() Corporate business continuity plan. The umbrella plan for the organization, the corporate plan documents the organization’s continuity program purpose, scope, policies, standards, and expectations, as well as the business continuity organization and reporting structure. Requirements for testing, training, plan reviews, and updates are detailed. The plan establishes procedures for how the board or upper level management will assess the long-term impacts of the disaster event on operations and provide advice and counsel for those carrying out business continuity plans throughout the organization. This plan may include guidelines for communicating with the press, the media, and—in global organizations—government agencies in countries where company facilities are located. Plans at all other levels throughout the organization follow the requirements and protocols set forth in the corporate plan.

Corporate business continuity plan. The umbrella plan for the organization, the corporate plan documents the organization’s continuity program purpose, scope, policies, standards, and expectations, as well as the business continuity organization and reporting structure. Requirements for testing, training, plan reviews, and updates are detailed. The plan establishes procedures for how the board or upper level management will assess the long-term impacts of the disaster event on operations and provide advice and counsel for those carrying out business continuity plans throughout the organization. This plan may include guidelines for communicating with the press, the media, and—in global organizations—government agencies in countries where company facilities are located. Plans at all other levels throughout the organization follow the requirements and protocols set forth in the corporate plan.

![]() Division, site, or geographical business continuity plans. These plans are often location-specific and, therefore, include procedures for responding to the hazards and potential disasters that may impact the site. Critical functions performed may also differ, and specific procedures and strategies needed to continue or resume operations at the location are outlined. Site plans follow all guidelines set forth in the corporate business continuity plan and coordinate the department plans within the division.

Division, site, or geographical business continuity plans. These plans are often location-specific and, therefore, include procedures for responding to the hazards and potential disasters that may impact the site. Critical functions performed may also differ, and specific procedures and strategies needed to continue or resume operations at the location are outlined. Site plans follow all guidelines set forth in the corporate business continuity plan and coordinate the department plans within the division.

![]() Department business continuity plans. Department plans contain clear, detailed strategies and procedures needed to continue or resume operations or provide services in the event of a disaster that compromises the ability of the department to carry out its identified critical functions within the recovery time objective. Supply chain department plans include procedures to be followed to fully restore supply chain operations in the event of an interruption. The IT department’s disaster recovery plan is its business continuity plan.

Department business continuity plans. Department plans contain clear, detailed strategies and procedures needed to continue or resume operations or provide services in the event of a disaster that compromises the ability of the department to carry out its identified critical functions within the recovery time objective. Supply chain department plans include procedures to be followed to fully restore supply chain operations in the event of an interruption. The IT department’s disaster recovery plan is its business continuity plan.

![]() Field operations business continuity plans, if applicable. Field operations plans provide guidance for employees such as service providers or field technicians working away from the organization’s facilities. These plans outline procedures that workers are to follow when a disaster occurs either in the field or at a company facility and that establish communications procedures to ensure that employees are kept informed of response and recovery efforts.

Field operations business continuity plans, if applicable. Field operations plans provide guidance for employees such as service providers or field technicians working away from the organization’s facilities. These plans outline procedures that workers are to follow when a disaster occurs either in the field or at a company facility and that establish communications procedures to ensure that employees are kept informed of response and recovery efforts.

This multilevel integrated approach allows for the activation of business continuity plans appropriate to the severity of the disaster and resulting impact on operations. Based on assessment at the time of an event, full or partial activation is initiated. For example, the destruction of the only facility where core business functions such as data processing and finance are conducted would likely require full activation at all levels. On the other hand, a small fire in a warehouse causing minor damage and resulting in no injuries, limited impact on operations, and no media attention might only require activation of the site plan.

Smaller organizations or organizations with a single location or very few facilities that are all located within a small geographical area may need only one plan, perhaps with a plan annex covering detailed procedures for individual departments or work units.

A well-crafted plan should be complete enough and easy enough to use that those not involved in its development can run with it to get the organization back in business.

Program Testing and Implementation

Once strategies have been developed and plans have been written, all elements of the program are implemented. This includes publishing and distributing the initial plan document and providing the appropriate level of training for all employees to enable them to carry out their business continuity role, however great or small.

Testing is conducted to validate that strategies meet the organization’s expectations and the plans accurately reflect strategies and provide sufficient guidance for those who will carry out the plans when a disaster occurs. It is only through testing that it is possible to identify insufficiencies or inaccuracies in plans and procedures and to determine whether carrying out the plans will allow operational recovery within the recovery time objectives. A first test of a new plan is almost certain to uncover needed revisions and enhancements.

Continuing to build program awareness and ongoing efforts to incorporate the program into the organization’s culture and day-to-day business operations are also important considerations when rolling out a new program.

Undertaking the tasks required to complete the initial continuity planning lifecycle can be daunting even for those experienced in such planning. It can be more so for those charged with developing and maintaining a business continuity program while maintaining a full schedule of day-to-day duties in today’s do-more-with-less business environment. Too often, the sheer volume of information that must be collected and processed seems overwhelming, and continuity planning must compete with other priorities. This can lead to false assumptions, rushed strategizing, and an untested and unworkable plan, or even worse: a planning project that gets put on the back burner, perhaps indefinitely.

There is a quote from the philosopher Voltaire that seems appropriate when considering the challenges of instituting a business continuity program. Roughly translated from the French, it reminds us that “The perfect is the enemy of the good.” The inability to get a perfect program in place in a short time should not be allowed to stop the planning process. Even a partial program results in an increased capability to manage disasters. Each step taken to prepare the organization to manage its risks is a step in the right direction in developing business continuity competency.

Avoiding Business Continuity Silos

All organizations are symbiotic. Each business unit supports all others either directly or indirectly; no one unit is able to do the organization’s work alone. Every organization is a complex interrelated grouping of business functions and activities. To remove any single unit unquestionably over a period of time causes operational slowdowns and bottlenecks, deterioration in the quality of the product or service, a financial hardship, and ultimately a total loss of the ability of the organization as a whole to function or deliver its product or service. To establish and maintain viable business continuity capability, all areas of the organization must be included.

The supply chain is a critical part of the organization’s operations and, conversely, all other business functions within the organization—even those not directly tied to supply chain business units—are critical for continued supply chain operations. While payroll may be the first identified non–supply chain business function to come to mind, marketing, facilities, human resources, and research and development are some of the other business units that are essential to continued supply chain operations.

Supply chain professionals realize that this necessarily cooperative, mutually beneficial, and interdependent working relationship is even broader than internal operations. Perhaps more than others within an organization, those involved in supply chain operations realize that businesses do not operate in isolation and that not all critical functions are internal. They see on a daily basis that each and every part of the external supply chain network is potentially as critical to continued operations as is each of the internal business units.

A Holistic Approach to Risk Management

Business continuity as part of an all-inclusive approach to managing risk needs to be viewed not as a separate process or activity but as a competency that is embedded in the organization, its operations, and its culture. Better decisions are made when planning is built into existing business functions so that it becomes an inherent part of key decision-making processes.

Responsibility for managing an organization’s risks may be scattered among several departments and functions. As previously stated, in organizations that first developed disaster recovery plans and later added a continuity program, it is not uncommon for IT to be assigned the added responsibility of developing and maintaining business continuity. Other departments may have responsibility for some part of the company’s continuing efforts to manage all types of disasters. If this is done with a less than perfectly coordinated integrated effort, it can result in possible gaps or overlaps.

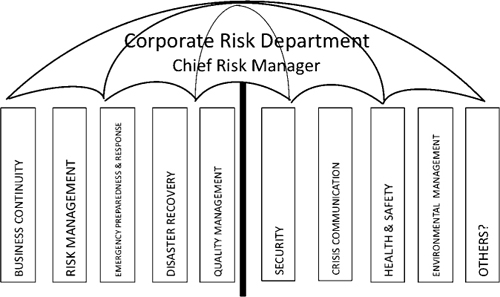

A slowly building trend in recent years, particularly in larger corporations, is to combine business continuity, disaster recovery, security, risk management/insurance, safety, etc., into one department with the head of the department reporting to an upper-level executive—for example, the CEO or COO. While it may at first seem that there is no direct relationship between these areas of an organization, on reflection, it should be clear that each function has a role to play in the continued well-being of the organization and its employees. Perhaps in the future it will not be unusual to see a new executive function and title— chief risk manager or chief risk officer (CRO)—for the person who is charged with managing all types of risks enterprise-wide. (See Figure 3-3.)

FIGURE 3-3.

A HOLISTIC INTEGRATED APPROACH TO MANAGING RISKS.

Wherever the business continuity function fits within the organization, it is critical that the program is given the full support and commitment of those at the executive level. In addition, the person heading it should have full accessibility to key decision makers.

Going Forward

It is not uncommon to find that a business continuity planning process was conducted without input from supply chain business units and that the resulting plans do not include supply chain continuity strategies. To improve supply chain continuity it is important to know to what extent the supply chain was included in the planning process.

![]() Meet with the person responsible for your organization’s business continuity program to learn more about the planning process currently being used.

Meet with the person responsible for your organization’s business continuity program to learn more about the planning process currently being used.

![]() Determine which supply chain business units were considered in the planning process and to what degree.

Determine which supply chain business units were considered in the planning process and to what degree.

![]() Learn how supply chain–related information was gathered and from whom.

Learn how supply chain–related information was gathered and from whom.

![]() If a supply chain representative is not currently a member of the planning group, suggest that one be assigned to actively participate in the planning process and serve as a liaison to coordinate the planning process in supply chain–related departments.

If a supply chain representative is not currently a member of the planning group, suggest that one be assigned to actively participate in the planning process and serve as a liaison to coordinate the planning process in supply chain–related departments.