CHAPTER 8

Business Continuity Plan Documents

DEVELOPING A BUSINESS continuity plan is a must in an organization’s overall efforts to prepare for, respond to, and continue or restore operations following a disaster. Because of an everchanging environment, constantly evolving technology, unforeseen circumstances, and other variables, a plan will not always be 100 percent successful as originally written. However, if it is comprehensive, well-written, and based on a sound planning process, a plan greatly increases the chance for successful response and recovery.

The Purpose of Business Continuity Plans

There is immeasurable value to be gained from the planning process, and a written plan is needed to capture and document the strategies and procedures developed during that process. The plan provides a general overview of the business continuity program (BCP) and becomes the operating manual when disaster strikes by providing the guidance needed to continue or restore operations. Information and directions detailed in the plan make it possible for the appointed business continuity teams to keep the business operational or to get it back up and running in the shortest time possible. The ultimate result of a continuity program documented in a well-crafted, workable plan may be the difference between the organization surviving and prospering, barely getting by, or even no longer existing following a disaster.

While one purpose of a plan is to codify the BCP, of equal importance is that it provide guidance and direction for carrying out continuity strategies when a disaster occurs. An organization’s business continuity plan needs to cover both the proactive and reactive elements of the BCP: proactive—the planning process and ongoing training, testing, and updating; and reactive—the actions to take when disaster strikes. The plan must be specific enough to provide adequate guidance and direction, but also generic enough to allow an effective response to each specific and unique disaster situation that may occur.

The proactive portion of the plan:

![]() Sets forth business continuity policy, such as emergency provisions and succession plans.

Sets forth business continuity policy, such as emergency provisions and succession plans.

![]() Identifies appropriate confidentiality and proprietary controls for the plan.

Identifies appropriate confidentiality and proprietary controls for the plan.

![]() Defines business continuity standards and requirements applicable throughout the enterprise.

Defines business continuity standards and requirements applicable throughout the enterprise.

![]() Identifies legal, regulatory, and audit requirements.

Identifies legal, regulatory, and audit requirements.

![]() Establishes the organization’s business continuity organization and reporting structure.

Establishes the organization’s business continuity organization and reporting structure.

![]() Establishes plan ownership, both of the overall program and of the individual plan components.

Establishes plan ownership, both of the overall program and of the individual plan components.

![]() Documents what is and what is not covered by the plan.

Documents what is and what is not covered by the plan.

![]() Provides guidelines for declaring a disaster and activating the plan—the who, be it an individual or group; the how; and the when—as well as related communications protocols.

Provides guidelines for declaring a disaster and activating the plan—the who, be it an individual or group; the how; and the when—as well as related communications protocols.

![]() Assigns responsibility for plan management at each level within the organization.

Assigns responsibility for plan management at each level within the organization.

![]() Establishes the process and schedule for testing and training.

Establishes the process and schedule for testing and training.

![]() Formalizes the process and schedule for plan reviews and updates.

Formalizes the process and schedule for plan reviews and updates.

The reactive portion of the plan documents strategies and provides the information and direction necessary for those responsible to successfully carry out and maintain the organization’s continuity program. It establishes:

![]() Business unit continuity team organization, staffing, and reporting structure

Business unit continuity team organization, staffing, and reporting structure

![]() What needs to be done, listing each business unit’s time-critical functions

What needs to be done, listing each business unit’s time-critical functions

![]() Who is responsible for doing it, including continuity team staffing and assigning responsibility for carrying out continuity procedures

Who is responsible for doing it, including continuity team staffing and assigning responsibility for carrying out continuity procedures

![]() How continuity teams will be notified and how plans will be activated

How continuity teams will be notified and how plans will be activated

![]() Why it needs to be done, addressing internal and external interdependencies

Why it needs to be done, addressing internal and external interdependencies

![]() When it needs to be done, based on recovery time objectives

When it needs to be done, based on recovery time objectives

![]() Where it will be done, including, if there are alternative location arrangements, where to go, who goes, how they get there, and the length of expected or maximum stay

Where it will be done, including, if there are alternative location arrangements, where to go, who goes, how they get there, and the length of expected or maximum stay

![]() How it will be done, including work-around procedures specific to each business unit

How it will be done, including work-around procedures specific to each business unit

![]() Resources needed for getting it done, including equipment and data

Resources needed for getting it done, including equipment and data

![]() Where resources will come from and how they will be delivered, including primary and backup sources

Where resources will come from and how they will be delivered, including primary and backup sources

As previously stated, the people who will implement the plan should be involved in its development. Doing so brings subject-matter knowledge to the process, provides an ongoing reality check, creates buy-in, and ensures that everyone involved is familiar with plan terminology. In addition, since this is a train-as-you-go approach, if the people who will be implementing the plan assist in writing it, the initial training process will be shortened significantly.

Developing the Plan

All the necessary ingredients are in place to put together the business continuity plan—hazards have been identified and mitigated, business functions have been ranked in order of criticality, and strategies have been developed together with an organizational structure to carry out the strategies. You are ready to develop the plan.

It is interesting to consider that this important document is one we hope to never have to use. Yet when it is necessary to do so, an effective plan can be the difference between the loss of your organization and its survival. It is therefore absolutely critical that plans are workable and provide teams with quality guidance.

Start with the basics, perhaps a mock-up of what the plan will look like when it is completed. Have a full understanding of the scope of the plan and where it integrates with other plans. Consider who will be using the plan and how to make it user-friendly. Creating an effective plan is a step-by-step process and not the place for taking shortcuts.

The Basics

Plans need to be both easy to use and easy to maintain. Some very basic guidelines can help accomplish this:

![]() For hard-copy plans, use a three-ring binder. When revisions are made, it’s easy to replace old pages with the revised versions, avoiding the need to reprint the entire document. It also makes it easy to take pages out to use during a disaster.

For hard-copy plans, use a three-ring binder. When revisions are made, it’s easy to replace old pages with the revised versions, avoiding the need to reprint the entire document. It also makes it easy to take pages out to use during a disaster.

![]() Avoid concerns about aesthetics. This is a working document. Focus on how it will work, not how it looks.

Avoid concerns about aesthetics. This is a working document. Focus on how it will work, not how it looks.

![]() Avoid concerns about whether the plan is long enough. Again, this is a working document. Keep in mind that heft does not equal value. It’s the value of the content, not the number of pages that is important. Make the plan long enough to define the program and give sufficient direction to those who will be carrying out the procedures . . . and not one word more.

Avoid concerns about whether the plan is long enough. Again, this is a working document. Keep in mind that heft does not equal value. It’s the value of the content, not the number of pages that is important. Make the plan long enough to define the program and give sufficient direction to those who will be carrying out the procedures . . . and not one word more.

![]() Use an easy-to-read font. Times New Roman in 12-point type is often recommended.

Use an easy-to-read font. Times New Roman in 12-point type is often recommended.

![]() Include a detailed table of contents and printed binder divider tabs. This makes it possible to find specific content without having to look through the entire plan.

Include a detailed table of contents and printed binder divider tabs. This makes it possible to find specific content without having to look through the entire plan.

![]() Include a glossary of business continuity terminology and all acronyms. Not everyone using the plan speaks continuity-ese.

Include a glossary of business continuity terminology and all acronyms. Not everyone using the plan speaks continuity-ese.

![]() Use single-sided pages, which makes it easier to update a single page or two and provides space for notes on the opposing blank page.

Use single-sided pages, which makes it easier to update a single page or two and provides space for notes on the opposing blank page.

![]() Avoid solid pages of text. Use short paragraphs, bulleted lists, diagrams, and charts for more user-friendly documents.

Avoid solid pages of text. Use short paragraphs, bulleted lists, diagrams, and charts for more user-friendly documents.

![]() Refer to people by title rather than name to avoid the need to make frequent changes to the body of the plan. List names together with contact information in attachments.

Refer to people by title rather than name to avoid the need to make frequent changes to the body of the plan. List names together with contact information in attachments.

![]() Avoid using footnotes.

Avoid using footnotes.

![]() Use clear, plain language.

Use clear, plain language.

![]() Use attachments for information that is frequently updated (such as lists of names or contact information). Attachments are located at the end of the plan document, making them readily available to use and easy to remove for updates and revisions.

Use attachments for information that is frequently updated (such as lists of names or contact information). Attachments are located at the end of the plan document, making them readily available to use and easy to remove for updates and revisions.

![]() Use appendices or annexes for lengthy, detailed information or instructions.

Use appendices or annexes for lengthy, detailed information or instructions.

![]() Build in a process to track all plan reviews and updates to serve as an audit trail.

Build in a process to track all plan reviews and updates to serve as an audit trail.

![]() Date and number each page of the document and use revision numbers to help ensure that everyone is using the same version of the plan.

Date and number each page of the document and use revision numbers to help ensure that everyone is using the same version of the plan.

![]() If your organization has document standards, take them into account as well when developing the plan.

If your organization has document standards, take them into account as well when developing the plan.

Plans: Mine, Yours, Ours

An organization’s business continuity program is not necessarily documented in a single plan. While one plan may be adequate to cover a small to midsize business, it may not be sufficient to encompass the entire organization of a business that is large or complex in structure. To avoid unwieldy multi-volume documents and to simplify the continuity process, plans and procedures can be broken down into more manageable, functional subplans. If there are multiple divisions, branches, or locations that are widely scattered geographically, each location and division should have its own business continuity team and subplan. In other words, each location has its own subplan and team to which the various departments or business units at that location report.

The business continuity team organization structure must be defined early on. The number of business continuity teams and the size of each team are determined by the number of people needed to carry out the continuity strategies and procedures and the size and configuration of the organization. (Appendix D includes five continuity team models as well as some guidelines for team member and business continuity center location selection.) While the team structure may vary, it is essential that each team have a leader with the authority necessary to make and approve decisions that enable the team to carry out its responsibility. This includes making work schedules and assigning personnel to carry out the schedules, allocating resources, and making expenditures necessary to carry out the strategies outlined in the plan document.

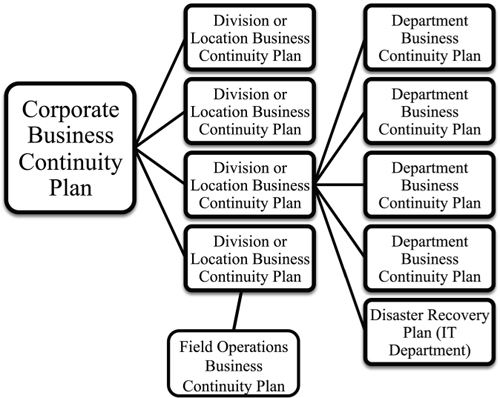

After the company establishes its business continuity organization structure, a coordinated and integrated “family of plans” is created. As shown in Figure 8-1, plans are developed and maintained to provide guidance for each level of the continuity organization structure:

FIGURE 8-1.

BUSINESS CONTINUITY ORGANIZATION AND PLAN STRUCTURE.

![]() Corporate business continuity plan

Corporate business continuity plan

![]() Division or location business continuity plans

Division or location business continuity plans

![]() Department/business unit business continuity plans, including IT’s disaster recovery plan

Department/business unit business continuity plans, including IT’s disaster recovery plan

Organizations that have employees who regularly work outside the company’s facilities, such as service or repair technicians or construction crews, may also include field operations business continuity plans.

It is not necessary that the detailed continuity procedures for all departments be shared throughout the organization. Although there are some differences in content among plans, each department plan needs to include only the information necessary for that business unit to accomplish its continuity responsibilities.

As an example, the continuity plan for a shipping and receiving department includes specific procedures for carrying out the identified time-critical functions following a disaster, whether that disaster results from a loss of IT system support, a contracted shipping company suddenly going out of business, or damage to the building requiring temporary relocation. Among the specific functions likely addressed are:

![]() Receiving and processing orders

Receiving and processing orders

![]() Picking goods for shipment

Picking goods for shipment

![]() Preparing goods for transit, possibly including hazardous materials

Preparing goods for transit, possibly including hazardous materials

![]() Determining the best method of shipment

Determining the best method of shipment

![]() Preparing labels, invoices, packing slips, purchase orders to carriers, and other documents

Preparing labels, invoices, packing slips, purchase orders to carriers, and other documents

![]() Maintaining an inventory of products, containers, and packing goods

Maintaining an inventory of products, containers, and packing goods

![]() Loading and unloading goods

Loading and unloading goods

![]() Unpacking and routing goods to the warehouse, storage, or internal recipient(s)

Unpacking and routing goods to the warehouse, storage, or internal recipient(s)

![]() Following safe storage and handling procedures, including those for any hazardous materials

Following safe storage and handling procedures, including those for any hazardous materials

![]() Meeting security and loss prevention requirements

Meeting security and loss prevention requirements

![]() Maintaining internal record-keeping systems

Maintaining internal record-keeping systems

![]() Tracking shipments

Tracking shipments

The people responsible for continuity procedures for shipping and receiving require detailed procedures for how to continue or restore these functions. Those at the corporate level do not, nor do other departments such as accounts payable or IT.

One advantage of having individual, stand-alone business unit plans is that in the event of a serious disruption that impacts only a single business unit, the situation can be handled by that business unit using its continuity plan without activating the company’s entire continuity organization. If the situation escalates, it is possible to then activate the larger business continuity organization.

While plans can be business unit–specific, they must also include procedures and mechanisms for all the various plans and the teams that carry them out to coordinate and communicate. When carrying out your department’s continuity strategies requires coordination or interaction with other departments, work closely with the continuity teams from those business units to ensure that the procedures in both or all plans are synchronized. Do not base your plan on what you think or assume other business units will do.

The Plan Development Process

Developing continuity strategies can be quite a challenge. Creating the plan should be approached as you would any major business document. Think in terms of a step-by-step process with multiple iterations of the plan.

Review requirements and guidelines. In preparing to develop the plan, review company business continuity standards and policies as well as any relevant industry standards, regulations, and audit reports. Also revisit the business impact analysis results, in particular your department’s time-critical business functions and recovery time objectives. If a department plan is being developed at the direction of a business continuity manager, he or she will likely be able to provide specific instructions, guidelines, and perhaps a template to use as a guide.

Establish the plan outline by identifying the topics to be covered. Again, if there is a business continuity manager, he or she may be able to provide a working outline that can then be tailored for your business unit.

Assign the development of sections of the plan to each team member. No one individual can develop a comprehensive plan singlehandedly. Involve the entire planning team and, to the extent possible, those who will be implementing the plan. This both shares the workload and brings more subject-matter expertise to the process.

Create a working first draft. Once all individuals have written their assigned sections of the plan, combine the sections, check for and correct inconsistencies in formatting, look for gaps and overlaps, and make any necessary changes and adjustments.

Circulate the working draft to members of the group for review and comment. If a department continuity plan is being developed at the request of the organization’s business continuity manager, ask that the manager review the work to date.

Conduct a tabletop exercise, which is a verbal walk-through of actions taken in response to a disaster, using only the plan draft. Have participants keep notes on plan deficiencies and areas needing correction, clarification, or a greater level of detail. During the exercise, consider if carrying out the procedures in the plan will result in meeting RTOs.

Incorporate identified improvements in a second draft. Revise, clarify, and enhance the plan based on comments from team members and what was learned in the tabletop exercise.

Repeat the process used for draft one. Circulate the second draft to group members for review and comment. Again, ask for a review by the business continuity manager or other individual who is responsible for the organization’s business continuity program. Then, conduct a second tabletop exercise.

At this point in the plan development process, consider some reality checks:

![]() If your organization has bargaining units, be certain that what is being asked of employees does not conflict with union contracts and possibly create a secondary disaster.

If your organization has bargaining units, be certain that what is being asked of employees does not conflict with union contracts and possibly create a secondary disaster.

![]() Check to make sure that the plan is not overdocumented. Remember, not a word more than is necessary. Documents that are too wordy or too lengthy can create confusion and lead to time wasted in trying to find needed information. If your organization has technical writers, consider whether it might be helpful to have them review the plan and offer some suggestions for improvement.

Check to make sure that the plan is not overdocumented. Remember, not a word more than is necessary. Documents that are too wordy or too lengthy can create confusion and lead to time wasted in trying to find needed information. If your organization has technical writers, consider whether it might be helpful to have them review the plan and offer some suggestions for improvement.

![]() As appropriate, have the plan reviewed and approved by upper management, auditors, the individual or department responsible for regulatory compliance, and other interested parties and groups to avoid having to make changes once the first full edition of the plan is complete.

As appropriate, have the plan reviewed and approved by upper management, auditors, the individual or department responsible for regulatory compliance, and other interested parties and groups to avoid having to make changes once the first full edition of the plan is complete.

![]() Get an additional review and approval from the organization’s legal counsel. This may result in the addition of a disclaimer in the front section of the document that includes a brief statement of the purpose of the document and a caveat that while the plan is regularly tested, revised, and updated, some elements of the plan such as RTOs can be affected by unforeseen circumstances when an actual disaster occurs.

Get an additional review and approval from the organization’s legal counsel. This may result in the addition of a disclaimer in the front section of the document that includes a brief statement of the purpose of the document and a caveat that while the plan is regularly tested, revised, and updated, some elements of the plan such as RTOs can be affected by unforeseen circumstances when an actual disaster occurs.

![]() Write the plan as though on the day the initial plan is finalized, every person involved in the writing process will walk out the door and never return. Check the plan to ensure that there is sufficient guidance so it can be carried out even if the people who wrote it are not available to explain or expand on any part of the document.

Write the plan as though on the day the initial plan is finalized, every person involved in the writing process will walk out the door and never return. Check the plan to ensure that there is sufficient guidance so it can be carried out even if the people who wrote it are not available to explain or expand on any part of the document.

Based on the results of the tabletop exercise and feedback from all who have reviewed the document, make any necessary changes. Then, once again, have all team members review the document and agree that it is ready for distribution. While two drafts may be sufficient, do not be taken aback if an additional draft or drafts are necessary. Creating a first version of a plan takes time, particularly when team members have little or no business continuity experience or have limited time available to devote to the project.

Avoid using the word “final” in referring to a plan document. A plan is never “done” but is always a work in progress. What you have at this point is a completed first version of the plan.

Print and distribute the document. It is not necessary that every employee of the company or the business unit have a copy of the full plan. Consider numbering all printed copies of the plan to control distribution and ensure that all plan holders receive all revisions and updates. If possible, conduct a meeting with those receiving copies of the document to go through the plan with them. Otherwise, include a cover letter reminding plan recipients of its history and purpose.

Maintain current copies of all plan documents off-site in the event a disaster prevents access to your buildings or computer systems are not operational. Consider making sure that each member of the business continuity teams can access their business continuity plan from any computer with an Internet connection as well as their mobile devices with appropriate password and other security protection.

Finally, congratulate yourself and the team members on a job well done.

Support Tools

In addition to receiving the actual plan, continuity team members need tools that make their jobs easier. Think in technology product terms. When you buy a new cell phone or printer for your home computer, there’s the big manual and the quick reference guide or basic steps in a one-page format. Along with the plan document itself (the big manual), each team member should be provided with some form of quick start guide. The information contained in this quick start guide is taken directly from plan documents and supports fast and accurate actions and decision making by the continuity teams, particularly in the first hours while everyone is getting organized and into continuity mode. A guide can include the criteria and process for activating the business continuity plan and the team, initial notifications to be made, and initial steps upon arrival at the assigned location.

A five-inch by seven-inch guide produced as a flip chart is one option for providing this information. Such a chart is inexpensive to produce. Each team member can have three copies: one for the office, one for home, and one for the briefcase or car. A pocket on the inside back cover can be included to hold a list of emergency contact numbers.

Provide each team member with an individualized checklist with actual tick boxes that outlines the initial steps they are to take when disaster strikes (see Figure 8-2). A five-inch by seven-inch laminated card format works well for this checklist.

FIGURE 8-2.

SAMPLE DEPARTMENT BUSINESS CONTINUITY TEAM ACTIVATION CHECKLIST.

![]() Report to the department’s business continuity center in accordance with the activation schedule or as directed.

Report to the department’s business continuity center in accordance with the activation schedule or as directed.

![]() Check in at the security desk; display your photo identification and sign the check-in list.

Check in at the security desk; display your photo identification and sign the check-in list.

![]() Report to the assigned work location and check in with the department business continuity team manager.

Report to the assigned work location and check in with the department business continuity team manager.

![]() Gather your copy of the business continuity plan and business continuity supplies and equipment.

Gather your copy of the business continuity plan and business continuity supplies and equipment.

![]() Review printed emergency procedures and building evacuation routes.

Review printed emergency procedures and building evacuation routes.

![]() Call the disaster recovery team at the number provided to establish your temporary log-in information and receive your temporary password.

Call the disaster recovery team at the number provided to establish your temporary log-in information and receive your temporary password.

![]() Determine if your assigned computer has access to the software and files you require; call the disaster recovery team for assistance, if necessary.

Determine if your assigned computer has access to the software and files you require; call the disaster recovery team for assistance, if necessary.

![]() Follow the assigned procedures outlined in the department business continuity plan.

Follow the assigned procedures outlined in the department business continuity plan.

![]() Initiate and maintain a written time record and log.

Initiate and maintain a written time record and log.

![]() Attend the initial team briefing conducted by the team manager.

Attend the initial team briefing conducted by the team manager.

The reverse side of the card can list emergency contact numbers and possibly directions to the pre-identified alternate work location.

You can provide easy-to-access information on laminated wallet cards or stickers that can be placed on the back of building access badges. Include business continuity contact information and initial plan activation steps. This same information can be produced in magnet form for team members to keep on their home refrigerator. Another alternative is electronic versions of this information, made available for team members to download onto mobile applications.

Organizations might also consider creating a Web portal to make alerts, disaster notifications, activation instructions, and information updates available to employees wherever they may be located.

Just as with the plan document itself, all of these tools— hard copy or electronic—must be updated with every plan revision, and as with plan documents, they should be dated. Incorrect or outdated information is dangerous no matter how it is delivered.

Avoiding Plan Gaps

When reviewing plans, I find that three important areas are often overlooked: damage assessment, communication, and deactivation.

Damage Assessment

A damage assessment is a critical function that must be performed as soon as conditions allow following any significant disruption or disaster. If there is no damage to the physical plant, the assessment focuses on the status of operations, such as whether shipments are being sent and received, employees are on hand to carry out time-critical functions, and computer systems support is available. If there is physical damage, the assessment provides an accurate picture both of the amount of physical damage done and the impact of the disaster on business operations. This in turn determines the level of business continuity team activation required and provides information needed to begin long-term planning for full restoration of operations.

Responsibility for conducting assessments is preassigned in the continuity plan, and detailed checklists for conducting each of the assessments are provided. In larger organizations, there can be a damage assessment team, perhaps headed by a member of the facilities and engineering staff. In many cases, a representative of one of the business units who is familiar with the department’s equipment and operational requirements is assigned to the assessment team. To avoid any possible risk to employees, if the disaster results in physical damage to facilities, assessments are conducted only when the building is safe, entry has been approved by public officials, and there is no threat to the safety and well-being of those conducting the assessment.

As a rule, three types of assessments are conducted:

1. An initial general assessment, conducted by walking through the site. The overall status of structures and contents is noted: what has been destroyed, what incurred major damage, what incurred minor damage, or what is unaffected. The initial assessment also includes verifying the availability of electrical power, telecommunications systems, water service, and computer systems. An external check is performed to determine whether there is access to structures and the site.

2. A detailed damage assessment, which provides a full and complete report of the status of facilities, infrastructure, office furnishings, equipment, supplies, inventory, and technical support systems. This assessment provides a more complete picture of exactly what has been damaged and whether it can be salvaged or restored or must be replaced, and the full impact of the event on operations. This assessment can also provide an initial estimate of the length of time required to restore operations. (Some organizations also opt to include an initial estimate of what losses may be covered by insurance.) This information, together with the nature of the disaster and the prognosis for reentering damaged buildings, is used to more accurately evaluate the situation and to determine specific strategies for restoring normal operations.

3. Additional assessments, which are conducted throughout the activation period either on a preestablished regular basis or as requested by the corporate business continuity team. Together with status reports received from business unit continuity teams, these ongoing assessments provide valuable information about progress being made and any issues that have arisen that will delay restoring full operations.

In some cases and with the prior approval of insurance carriers, damage can be documented using date-and time-stamped video or still-photo media so that cleanup, repair, and initial restoration procedures can be initiated more quickly.

Communication

While disaster communications issues were discussed in Chapter 7, it is important to document the continuity communications requirements and detailed procedures in the plan document. The plan must cover the who, the how, and the when of communicating with the corporate business continuity team, other business unit continuity teams, and employees in addition to customers, suppliers, other critical business partners, and stakeholders.

This critically important communication starts with having a process and assigned responsibility for all initial notifications and updates. Make certain that the plan identifies and details all the people, organizations, and other entities you need to contact immediately upon activation of the plan, throughout the business continuity process, and through full deactivation.

Communication also requires the means to receive and relay messages and information. The department that manages the organization’s telecommunications likely has communications mitigation strategies built into its department business continuity plan, such as fail-over phone switches, phone lines from multiple carriers, and phone lines entering the building at different locations. Some organizations opt to use nongeographic phone numbers that divert calls made to the company’s existing number to an alternate landline or cellular location in a disaster situation. Landline phones, cellular phones, satellite phones, voice over IP, and e-mail are just some of the options for communications redundancies.

External communications must be considered as well. You do not want customers and clients to think the worst if they have heard that your organization experienced a major emergency or disaster and they have not heard directly from a representative of your organization in a timely manner. You do not want these customers and clients to consider looking for another source for the service or product you provide. One approach for organizations with call centers is to use the call center and call center representatives as a business continuity contact center, with documented plans and procedures for doing so included in the business continuity plan. An alternative is available from some telecommunications providers that field calls made to your company at a virtual call center facility staffed by their employees. Calls are answered using your organization’s name, and messages are taken and then forwarded in accordance with your instructions. While calls not being answered by a company employee is not the ideal situation, even worse is a customer’s call going unanswered or a supplier or other business partner hearing a recorded message that your phone number is out of service.

Each department’s plan needs to include directions for when and how to use these alternate communications methods.

Deactivation

Another important process to detail in the plan is the deactivation phase—how to return to normal operations once the disaster has passed. This is referred to by IT folks as “failing back.” Deactivation is accomplished in logical steps that require attention to details such as switching phone lines, recalling employees, restoring or rerouting deliveries and shipments, ensuring that all files are backed up, returning supplies and equipment, completing and submitting all documentation, and participating in debriefings. Omitting detailed deactivation procedures from a plan can result in a secondary disaster that can be more destructive than the original event.

Reviews and Updates

Plan documents—an essential component of your BCP— are not static and are never complete, never finished. Plans are a perpetual work in progress and, like people and fine wine, they should grow, mature, and get better with time and experience.

The value of even the very best business continuity plan deteriorates quickly if the plan does not keep pace with changes in the organization. A great plan today, left sitting on a shelf for six months or more, likely begins to become out-of-date. Think back over the last year and list the changes that have taken place in your organization as a whole and in the supply chain business units particularly. This short exercise likely indicates the importance of regular plan updates.

Best practices call for conducting a full review or formal audit of the entire plan not less than annually. Interim revisions may be necessary as well as a result of substantive changes in any information contained in the plan, including lessons learned from tests and exercises. The BCP must be revisited regularly to determine whether changes or enhancements in the plan are necessary. On an annual basis, the hazard assessment and business impact analysis also must be reviewed to determine whether changes in strategies and plans are needed. Perhaps the organization’s priorities have changed or there are new locations, new product lines, or new processes. Any of these or other operational changes can create a need for plan revisions at one or multiple levels.

Just some of the triggers that signal a need to review and update plans are changes in:

![]() Business continuity staffing

Business continuity staffing

![]() Suppliers, contractors, and/or outsourcing companies

Suppliers, contractors, and/or outsourcing companies

![]() Contact information

Contact information

![]() Operational procedures

Operational procedures

![]() Technology

Technology

![]() Physical plant

Physical plant

![]() Equipment

Equipment

![]() Hazard information

Hazard information

![]() Company policy

Company policy

![]() Regulatory requirements

Regulatory requirements

![]() Audit requirements—internal or external

Audit requirements—internal or external

![]() Technology such as manufacturing, IT, or telecommunications

Technology such as manufacturing, IT, or telecommunications

![]() The organization’s size, either growth or downsizing

The organization’s size, either growth or downsizing

One of the greatest challenges in maintaining current information in plan documents is the ongoing changes in contact information for employees, customers, critical suppliers, and contractors. A wrong contact name or telephone number can have a negative impact on the amount of time required to restore operations. Partner with your human resources department to keep employee contact information current, and with accounts payable or procurement to maintain current names and contact information for suppliers and other business partners. One way to help ensure that the plan has up-to-date information for external contacts is to periodically give a copy of the plan’s contact attachments to an employee and have him or her place calls to the numbers listed to verify that the information on the list is accurate and current.

To help manage the impact that ongoing organizational changes make in business continuity programs, establish documented policies supported by management that require all changes that impact continuity be reported to the person who manages the BCP. If the organization has a change management department or function, link business continuity to the established change management process.

The Effect of Mergers and Other Reorganizations

In today’s business environment, mergers, acquisitions, takeovers, and divestitures are the norm, as are major reorganizations. These are all significant changes and as such require a thorough review of hazards, business impacts, strategies, procedures, and plan documents.

There are challenges in maintaining an effective, integrated continuity program following any merger, acquisition, or other far-reaching organizational change. A fact at times not fully considered is that when two or more organizations merge, whatever the reason, the result is a new organization. The new organization is likely larger, has more geographical locations, and offers a wider range of products and services. In addition, it is unlikely that the merging entities have the same suppliers, outsourcing companies, and other business partners.

From a supply chain perspective, this new organization must continue to meet customer needs and requirements within a new organizational structure. The good news is that with the new, larger company, there are likely more business continuity strategy options. The question, however, is whether we use your business continuity plan or my business continuity plan. Reaching consensus on how to proceed is particularly difficult when both organizations bring mature continuity programs based on sound planning practices to the table. The answer is that we must create our plan, a new plan that will best meet the continuity needs of the new organization.

And while it may be possible to incorporate the best elements of both plans into a new improved plan, in some situations it may be necessary to begin anew. Combining existing plans may not result in a continuity program that meets the needs of the newly formed organization when a merger results in a completely different organizational structure; a significant number of new departments, divisions, or locations; the total reprioritization of core processes; or in the event the merger involves two or more extremely diverse cultures. A collaborative effort in developing a new program may be necessary.

Many of the same issues and challenges must be addressed when individual business units have unilaterally developed business continuity plans that must then be incorporated into a cohesive enterprise-wide continuity program.

Here are just some of the supply chain business continuity issues you may need to deal with when creating a new business continuity organization:

![]() Combining differently configured supply chains

Combining differently configured supply chains

![]() Integrating people and teams from different supply chain organizations

Integrating people and teams from different supply chain organizations

![]() Identifying and addressing additional supply chain risks

Identifying and addressing additional supply chain risks

![]() Working with supply chain systems such as Materials Requirements Planning or other IT support systems that are not fully compatible

Working with supply chain systems such as Materials Requirements Planning or other IT support systems that are not fully compatible

![]() Working with communications systems that are not fully compatible

Working with communications systems that are not fully compatible

![]() Meeting additional regulatory or legal requirements

Meeting additional regulatory or legal requirements

![]() Working with organizational cultures that may vary greatly

Working with organizational cultures that may vary greatly

Conversely, combining two or more organizations can present opportunities, such as:

![]() Creating additional continuity strategies as a result of having more locations, operational redundancies, and skilled personnel

Creating additional continuity strategies as a result of having more locations, operational redundancies, and skilled personnel

![]() Combining the best elements of two programs into a new program that results in a greater overall capability

Combining the best elements of two programs into a new program that results in a greater overall capability

![]() Creating continuity teams whose combined members contribute a wider range of experience, capabilities, and know-how

Creating continuity teams whose combined members contribute a wider range of experience, capabilities, and know-how

Full advantage can be taken of these opportunities and others by addressing business continuity planning issues during the initial planning stages of a merger or acquisition. This can include:

![]() Determining how the business continuity programs will operate while the merger or acquisition process is taking place

Determining how the business continuity programs will operate while the merger or acquisition process is taking place

![]() Identifying and planning for new risks that may arise during the merger process, a time that is definitely not business as usual

Identifying and planning for new risks that may arise during the merger process, a time that is definitely not business as usual

![]() Addressing the restructuring of the business continuity planning group and forming one group that equitably represents both or all the organizations

Addressing the restructuring of the business continuity planning group and forming one group that equitably represents both or all the organizations

![]() Establishing a process to review all supply chain contracts to determine if there are overlapping contracts and whether some contracts need to be renegotiated, terminated, or allowed to expire as a result of the merger

Establishing a process to review all supply chain contracts to determine if there are overlapping contracts and whether some contracts need to be renegotiated, terminated, or allowed to expire as a result of the merger

![]() Conducting a thorough review and audit of both existing BCPs to determine whether the most advantageous path is to combine the best elements of both or all existing programs or to develop a new, fully integrated program that meets the business continuity needs of the newly created organization

Conducting a thorough review and audit of both existing BCPs to determine whether the most advantageous path is to combine the best elements of both or all existing programs or to develop a new, fully integrated program that meets the business continuity needs of the newly created organization

Whatever the reason for the revision or update, ensure that all plan holders receive all updates and revisions. If the changes are substantial, provide training for all those with continuity roles to familiarize them with the new plan and their new roles and responsibilities. Check to be certain that all electronic and hard copies of the plan and the related tools and guides are updated.

True story: It was summer during my initial on-site visit with a new client on the East Coast when I sat down to talk with a person who had been a member of a disbanded planning group that had been assigned to write the company’s original business continuity plan. When I asked to see a copy of the plan document, the individual pointed to an open office window and said, “Sure, it’s right over there.” Lo and behold, there was the plan binder propping open an office window. The path from business continuity document to window prop was determined by several factors:

![]() While it was titled “business continuity plan,” the plan focused only on IT with no consideration of the business of the entire business.

While it was titled “business continuity plan,” the plan focused only on IT with no consideration of the business of the entire business.

![]() Few people outside the original planning group even knew the plan existed.

Few people outside the original planning group even knew the plan existed.

![]() The plan had never been tested.

The plan had never been tested.

![]() People identified as members of the business continuity team had not been notified that they were members, let alone received any training.

People identified as members of the business continuity team had not been notified that they were members, let alone received any training.

![]() The plan was three years old and had never been reviewed or updated, nor was there any mechanism for doing so.

The plan was three years old and had never been reviewed or updated, nor was there any mechanism for doing so.

![]() Once the plan document was written, the planning group was disbanded and no one was assigned permanent ownership of the plan.

Once the plan document was written, the planning group was disbanded and no one was assigned permanent ownership of the plan.

![]() The project had as its goal a business continuity plan rather than a business continuity program.

The project had as its goal a business continuity plan rather than a business continuity program.

A Sample Basic Plan

While I am always somewhat hesitant to provide a sample continuity plan, I understand the desire to see an example of what a plan looks like, what information it contains, and how it is formatted. Appendix E contains three sample documents:

1. Table of contents for a corporate business continuity plan

2. Table of contents for a department or other business unit plan

3. Basic plan for a department or other business unit

As the sample plan is generic, it will not necessarily work as a model for every supply chain business unit to develop its plan document. Use the table of contents to develop an outline. Always focus on what your business unit needs to continue or resume operations. Include sufficient direction and guidance to enable team members to carry out their continuity responsibilities. Keep in mind your organization’s overall continuity requirements and ensure that your plan integrates and coordinates with all other plans.

A great deal of specific relevant information in the document is contained in its attachments. There, updates can be incorporated into the plan without having to reproduce the entire document. Attachments might be made up of contact lists, resource lists, sample forms, continuity organization charts, detailed procedures needed to carry out your business unit’s continuity strategies, instructions for setting up operations at alternate work sites, and an action checklist for each team member.

If you wish to do additional research on developing plans, sources for guidance include the Internet, insurance carriers, purchased plan development software, books, classes, and consultants.

There are quite a number of plan documents available on the Internet, including some that are identified as business continuity plans though in reality they are disaster recovery plans. A great majority of the plans available online are for government agencies, educational institutions, and not-for-profit organizations. Not surprisingly, it is rare that a company publicly shares its continuity plan, as the plan may contain proprietary information or the company may not wish to provide its competition with information about its plan. In addition, companies have invested significant resources in developing their plan and see no value in making the finished products available to others.

Your insurance carrier or broker can often provide guidance with some portions of the planning process, including plan development. There are also software packages on the market that can assist with creating plans. As with all software, be sure to check into all the pluses and minuses and conduct a thorough selection process if you opt to go that route. Avoid a fill-in-the-blanks product.

Helpful information is also available from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Department of Homeland Security websites.

Going Forward

For any organization, remaining up and running no matter what the challenges is good business. The business continuity plan is an essential part of a business continuity program. It is where continuity team members turn if there is a disaster or serious interruption.

A good plan that successfully guides the team through a crisis situation can be the difference between success and failure in continuing or restoring time-critical business functions. It is therefore absolutely critical that the plan is workable and that it provides information of sufficient quality and detail to guide the continuity team through the disaster.

![]() If your organization or your department has a business continuity plan, review the sections of the plan that cover your job function to determine if it provides the information and guidance needed for you or an alternate to successfully carry out your role in the business unit’s continuity procedures. If not, take action to make the necessary updates and improvements.

If your organization or your department has a business continuity plan, review the sections of the plan that cover your job function to determine if it provides the information and guidance needed for you or an alternate to successfully carry out your role in the business unit’s continuity procedures. If not, take action to make the necessary updates and improvements.

![]() Check your copy of the business continuity plan to be certain that it contains the most current versions of the basic plan and all appendices and attachments.

Check your copy of the business continuity plan to be certain that it contains the most current versions of the basic plan and all appendices and attachments.

![]() Using the sections of this chapter on “Developing the Plan” and “The Basics,” review your existing plan to identify possible areas for improvement.

Using the sections of this chapter on “Developing the Plan” and “The Basics,” review your existing plan to identify possible areas for improvement.

![]() Review plan attachments to determine if contact information needed by your department is included and current.

Review plan attachments to determine if contact information needed by your department is included and current.

![]() Meet with a representative of the telecommunications business unit to gain an understanding of the company’s disaster communications capabilities and strategies, and include detailed directions for using redundant or alternate communications methods in your business unit’s continuity plan.

Meet with a representative of the telecommunications business unit to gain an understanding of the company’s disaster communications capabilities and strategies, and include detailed directions for using redundant or alternate communications methods in your business unit’s continuity plan.

![]() If there is no plan for supply chain departments, meet with supply chain managers to outline the contents of a plan.

If there is no plan for supply chain departments, meet with supply chain managers to outline the contents of a plan.

![]() Determine if there are tools to support the plan such as checklists and guides.

Determine if there are tools to support the plan such as checklists and guides.

![]() If there are no tools or aids, consider developing some basic guides for your department, perhaps starting with a list of emergency contact information in a format such as a laminated wallet card.

If there are no tools or aids, consider developing some basic guides for your department, perhaps starting with a list of emergency contact information in a format such as a laminated wallet card.