RULE # 5

You Get What You Negotiate, Not What You Deserve

CONGRATULATIONS! You have put value creation to work in your résumé, networking, and interviews. The end result is a job offer. The hunt is over. Now seems like a good time to relax. You tell yourself that you will take a few weeks off so you are rested and ready to hit the ground running.

Hold on! Did you get everything you set out to achieve when this process first started? Does your offer of employment have all of the conditions you want? Are the responsibilities of your next job as clear as they should be so you and your new employer will be happy together? These are only a few of the questions you need to consider before your new deal is final and you can relax.

During the time when changing jobs (and careers) was the exception rather than the rule, negotiation of the conditions of employment was not a skill worth perfecting. People expected to be at the same job for a long time, perhaps even until they retired. But times have changed. Today, negotiation skills are an absolute necessity for successful career management. The truth is that you are in your strongest bargaining position during the time between when a job is offered and when you accept it. The company has examined your credentials, invited you in for interviews, and decided to make an offer it hopes you will accept. You have more leverage now than at any other time. Take advantage of your strong position.

Taking advantage doesn’t mean that you should make outrageous demands. It means that before accepting, you should review the situation and make sure you have what you wanted. Unless you take the time now to do some serious thinking, you run the risk of overlooking important considerations. Once you start a new job, it may be too late to do anything about them.

Here is a telling example. Joanne was so relieved to have finally landed a job that she accepted an offer of employment immediately, and she agreed to a start date without further discussion or review. “I have been out of work seven months,” she thought. “I am happy and relieved just to have a job. Besides, people here seem flexible. If anything comes up, I’m sure we can work it out.”

Joanne’s feelings of goodwill were typical of the postoffer honeymoon, during which everyone is on his or her best behavior. Only later did Joanne discover that her new company counted tenure differently for vacation days. Her annual vacation time from the three weeks she had earned with her previous company was reduced to one week. Even worse, giving up two weeks of vacation may have been unnecessary. Later, she met fellow employees who had negotiated additional vacation days at their time of hire. This was doubly galling because the rate of vacation accrual was slower, and she would have to wait an additional five years just to get to two weeks. Six months into her job, her request for additional vacation time was turned down.

Perhaps you will review the offer you received, find out you are completely satisfied, and enter your new situation looking forward to work. But there is also a good chance you will discover opportunities to improve the conditions of your employment. You don’t know what opportunities exist unless you learn how to look for them. The people who do that get what they negotiate, and not what they deserve.1

When you are offered a job, it is perfectly acceptable to say, “I really appreciate that we are at this point. I would like to take a little time to review the offer. Let me sleep on it and I will get back to you. What date works best?” Reputable companies understand the need for a little time between when an offer is made and when the candidate accepts. It is standard operating procedure. Be extra cautious if you are told, “Accept the offer now, or the deal is off.”

Be Prepared to Negotiate

In labor negotiations, the parties don’t wait until the contract expires to begin preparation for the next one. Likewise, the minute you know you might have to look for another job, you should give thought to what you want in a new position. This should be done well before a job offer is in hand.

At the very beginning of your job search you can effectively prepare for the negotiation phase by drawing up a list of things you want in a new position. Expect the list to change as you move through the job-search process. Date the list (and subsequent editions) to keep track of how it evolves. Once you complete an initial draft, put it away for review later after the completion of each major step in the job search. The items listed below are typical of the lists we have seen over the years:

Desirable Characteristics in My New Job (Middle Management)

![]() No more than 30 percent travel

No more than 30 percent travel

![]() Company car

Company car

![]() Company-paid relocation

Company-paid relocation

![]() Bonus opportunity of at least 40 percent

Bonus opportunity of at least 40 percent

![]() Job-search support for spouse

Job-search support for spouse

![]() “Business casual” dress code

“Business casual” dress code

![]() Tuition reimbursement

Tuition reimbursement

![]() Adoption-support programs

Adoption-support programs

![]() Company-paid health-club membership

Company-paid health-club membership

![]() Day care on-site

Day care on-site

![]() Work-life balance policy

Work-life balance policy

![]() Preference for internal promotions

Preference for internal promotions

The list for more entry-level positions might be less specific, but the process is the same.

Desirable Characteristics in My New Job (Entry Level)

![]() Team-oriented supportive culture

Team-oriented supportive culture

![]() History of internal development and promotion

History of internal development and promotion

![]() Bonus opportunity

Bonus opportunity

![]() Two weeks’ vacation

Two weeks’ vacation

![]() Financial stability

Financial stability

![]() No outsourcing

No outsourcing

![]() Company-paid relocation

Company-paid relocation

![]() Good reputation for hiring strong performers

Good reputation for hiring strong performers

![]() Performance-based culture

Performance-based culture

![]() Belief in work-life balance

Belief in work-life balance

![]() Challenging environment

Challenging environment

![]() Pay for performance

Pay for performance

![]() Health-care benefits

Health-care benefits

![]() “Business casual” work environment

“Business casual” work environment

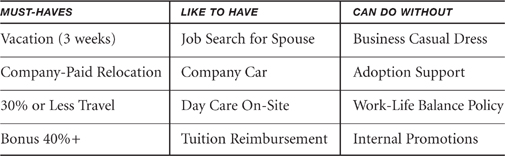

Be sure the list represents your values and the things you feel you need in a new job. You must make distinctions, though, because not all of what you want will be available at the company, and it probably won’t concede on every single item. Now, go back through the list and divide it into three categories: (1) What you absolutely must have, (2) What you would like to have, and (3) What you would like to have but can do without.

Try to put an equal number of items into each category. This is called a “flat” arrangement because it forces you to make hard choices early in the process, rather than loading everything into a couple of categories. As you come to understand the realities of your particular job market, these choices will likely move back and forth between the categories, giving you practice at making the compromises we all make as each job opportunity arises. For example, the unwillingness to relocate is usually one of the items that moves back and forth. For most, it is an unattractive alternative until you come face-to-face with relocating to another city or you will continue to be unemployed. Continual reevaluation of the list will also help you keep what’s important to you in the forefront of your mind as you start your negotiations.

An example of how a middle-management list might be divided is shown in Figure 5.1. Use the same process for more entry-level positions.

Know When to Negotiate

Preparation is helpful, but timing is crucial. If you communicate your preconditions to a company before you even land the job, you are violating the rule about delivering value first and foremost. The company will judge you against other job candidates, and those candidates may not stipulate any conditions. They will conduct their negotiations at the right time—after they are offered the job.

Jennifer learned this lesson the hard way. As for many professionals today, her life was filled with overlapping and sometimes conflicting roles—mother of two small children, married to a career-oriented professional, and needing two incomes to maintain their standard of living. Her ideal job would include the opportunity to work from home at least once or twice a week, as well as more flexible hours on days when she has to be in the office. Consequently, she specifically looked for companies that recognized the importance of work-life balance.

Jennifer decided to mention these preferences as often as appeared reasonable early in the interviewing process. She did not want to get all the way to the end and have the conditions be an insurmountable stumbling block. Unfortunately, she also gave the impression of less interest in what it would take to be an outstanding employee and more interest in what was in it for her. Even though the company had adopted a work-life balance as one of its core values, the job offer went to another candidate with similar requirements who had emphasized those needs less frequently during the interviews.

Jennifer understood her situation perfectly well. The problem was that she tried to negotiate the conditions of her employment too early. She allowed her work-life balance concerns to become too large a part of the decision-making calculus. That is, she got it backward. Companies hire people because of the perceived value they create, not because of the needs individual candidates have. While many companies are willing to accommodate those needs, the key factor in hiring is always value creation. Jennifer’s forcing of the issue made her commitment to value creation look questionable, as well as unprofessional.

Generally speaking, no matter how important an issue is to you, you should raise it in earnest when you are in your strongest bargaining position—after an offer has been extended but before you accept. Until then, keep the conversation general. For example, it would be okay to ask, “I understand your company has a particular commitment to work-life balance. Can you please help me understand your policy?” Take note of the answer you get, but don’t push it. In the meantime, look for other ways to determine if a particular company is right for you. For example, to test the company’s commitment to work-life balance, Jennifer could have sought out women employees with children and learned firsthand from them how flexible the company was about hours. Perhaps she also could have found the information on the company website, in magazine articles, and/or from former employees. You don’t have to ask your future boss directly.

Negotiation Outcomes

Of the four possible outcomes to a negotiation, three should be avoided. The four are:

1. Stalemate

2. I win/you lose

3. You win/I lose

4. Win/win

Undesirable outcomes result most often when one or both parties misunderstand the bargaining stage of the job-negotiation process. Keep in mind that you are at the most desirable point in your job search. You want a job, have found an employer that offered one, and have a most favorable environment for negotiation. Win/win is the most desirable outcome.

In the heat that sometimes accompanies negotiation, both parties can forget that most of what they are trying to accomplish has been completed. Often the last step to the end goal is a short one. Poorly understood negotiations run the risk of doing damage to a future relationship and may reach the point of ruining the deal altogether.

STALEMATE

A stalemate occurs when one party to a negotiation wants something the other party is unwilling to give. This happened to Bart when he insisted that his new salary be at least a 10 percent increase over what he had earned previously. He had always believed that each new job should be bigger and better than the previous one. To him, the most important measurement of career advancement was salary progression.

But the company’s offer was a full 10 percent below what Bart had previously earned. Though the initial conversations about salary level were pleasant, neither side was willing to give an inch. Neither could get past a fixed point of view. The company wanted to pay only so much for the position, and Bart wanted a clear demonstration of career progression. They were at a stalemate.

Alternative forms of compensation during the first year of employment could have been considered as a way to make up the difference. These options include sign-on bonuses, extra vacation, or commitments to do salary reviews at six-month intervals to determine if an employee’s contribution warrants additional consideration. A compensation package can have many components, so make sure you try different avenues to reach the same goal. A show of flexibility can induce the other side to be flexible as well.

I WIN/YOU LOSE AND YOU WIN/I LOSE

These two positions can be viewed similarly because they are mirror images of one another. Both parties see negotiation as a zero-sum game in which a gain for one side is a loss for the other. This happened to Steve when he listed his job priorities but did not sort them further. He negotiated for all the items as though losing any one of them was a gain for the company he was negotiating with. He forgot that, at this stage in his job search, he and the company agreed on many more things than they disagreed on. Now would have been a good time to revisit his list to see what trade-offs were possible.

So, pay special attention to the category of things that would be nice to have but you could do without. You may be able to trade some of those as “give-backs.” Also, reassess those priorities that were once seen as nonnegotiable “must-haves.” Given the specific conditions of the job offer, some of those items may now seem less important.

WIN/WIN

Mutually satisfying situations are created when you discover common ground on which both parties can agree and each side gets enough of what it needs to feel good about the outcome. Win/win outcomes provide the basis for the ongoing relationship that you will have if you take the job.

Not that every negotiation will result in a win/win, but with a little bit of skill and perseverance, compromise is possible most of the time. Here is where good listening skills definitely come into play. Since an immediate answer is not required, you don’t have to formulate one before the offer has been fully presented. Listen carefully all the way to the end of the offer presentation. Offers of employment usually lead with the most positive features: “Tom, we are pleased to extend this offer to work for us at the salary we agreed to.”

But the devil is always in the details, and eventually they will mention any downsides—and sometimes they fail to mention them at all. Either way, you need to pay attention. Regardless of any disappointment you feel at first about certain conditions, maintain the positive attitude that is part of any win/win negotiation. You may need the goodwill it generates later if the back-and-forth negotiation gets testy. You would need years of practice in negotiating the conditions of your employment to become an expert negotiator. Most likely, you do not want to change jobs and careers that often, but let’s move to discussing some of the basics of skillful negotiation.

Seven Rules for Skillful Negotiation

You can become competent enough to get what you want as long as you understand some basic rules. These seven rules for skillful negotiation are designed to make you a proficient negotiator in your own cause. Three of the seven (3, 4, and 7) can be found in almost any good book on negotiation; the other four (1, 2, 5, and 6) are unique to this book.

1. NEVER TURN DOWN A JOB BEFORE IT IS OFFERED

You may wonder if anyone really does that. But it happens all the time, and that is why we mention it first. Remember, you get what you negotiate, and that can include a variety of added benefits. You can collect extra compensation, as we have seen, and even a better job title.

Donna didn’t know that, and she paid the price. She had worked hard to climb the corporate ladder and was pleased when she finally was promoted from a director to vice president. Yet her excitement was short-lived owing to a restructuring in which management layers were thinned and her newly attained vice president’s position was eliminated. The outplacement firm warned that the trend toward flattened organizational structures had gained momentum, and she would likely find fewer VP positions in the industry as a whole. She viewed taking another director-level position as a step backward. For that reason, she had a VP title on her list of “must-haves.”

In the beginning stages of her search, Donna declined an opportunity to interview for a director of marketing position for the U.S. division of a multinational beverage company. The firm had only one VP-level marketing position, and that had just been filled. She felt the job was in a smaller division and at a lower level than she wanted.

A couple of months later, she agreed to be a reference for a former colleague who interviewed for the same director of marketing position Donna had turned down. When she was notified that her colleague was the successful candidate, Donna called to offer congratulations. To her shock, she learned that the position had been upgraded to the VP level, with a corresponding adjustment in salary.

“How did that happen?” Donna asked.

“It was part of the negotiation. The job had been identified as a future VP-level position, but they were willing to upgrade it now to get the right person.”

Titles, salary levels, and many other aspects of a future job can be negotiated. But unless you get the offer, you’ll never find out. If some aspect of a new job becomes a nonnegotiable that you cannot resolve, you can always turn the job down. But don’t turn down an otherwise attractive opportunity until you have had the chance to negotiate.

Another reason people turn jobs down before they are offered is to protect their self-esteem. If they suspect their chances of getting an offer are not as good as they should be, they sometimes withdraw from the competition. A lot of excuses come into play: “It would have been a step backward.” “I’ve done that job before.” Needless to say, turning jobs down before they are offered limits your options.

2. USE THIRD-PARTY NEGOTIATORS WHEN POSSIBLE

Using an outside party to negotiate a better deal gives you a chance to raise sensitive issues safely. You can ask these touchy questions directly; however, the negotiation process may be more comfortable for both sides if you go through a third party.

For example, Ruth was a single parent with a special-needs child. From time to time she had to either leave work early or come in late when her caregiver required more flexible hours. She was reluctant to bring the issue up before the offer sheet was signed, and she approached the search firm about the best way to proceed. The search consultant knew the company well, recognized its willingness to deal with such issues, and advised Ruth to alert the references from her previous job to include positive comments about how she handled the situation—that her circumstances in no way ever affected the quality of her work and required special arrangements only two or three times a year. The search consultant presented the information to the company and likened the situation to that of another of the employees the company liked very much. Everyone was satisfied and the job offer went forward without a hitch.

If you thought the search firm was paid by and working for the company, you are correct. Is it smart, therefore, to let the search firm do your bidding? Yes, and it works almost every time. Here is why. Remember, you are at that special stage during negotiations when you have maximum leverage. That leverage extends to search firms as well. That is, everyone concerned thinks you are the best candidate for the position. The search firm has satisfied its basic obligation to the client and is now looking for its cut. The firm has extra incentive to negotiate any remaining items as quickly as possible. At this stage of the game there are plenty of incentives to achieve a win/win result.

Third parties, such as search firms, can probe sensitive topics like salary, job title, time off, and other factors without creating the appearance that your demands are unreasonable or that you are difficult to deal with. Some direct negotiations become so contentious that they poison the employer/employee relationship before it gets going. Rather than hitting the ground running, you spend your first few months on the job mending fences.

Generally, the lower the position in the organization, the less you need a third-party negotiator. For senior-level and upper-middle-management positions, an employment lawyer is highly recommended, however. For most situations, it is not a good idea to put your lawyer between you and a new employer unless it is the norm to do so. Negotiations with professional athletes, authors, entertainers, actors, and very senior-level people often involve third parties. The contracts can be complicated and require considerable expertise. Most lawyers, however, work better behind the scenes, pointing out areas for additional negotiation and where clarifications are needed.

Because the revolving employment door could start spinning at any time, many executives are advised at this time to also negotiate the conditions of their terminations, including severance pay, outplacement, stock-option exercise rights, and other matters. Some executives have even negotiated the continued use of the company plane and an expense account to carry them through to the next position.

3. GET IT IN WRITING

Most job-hunting books advise you to not resign from your old job until you have the new offer in hand. Even then, an offer may confirm intent, but it may not actually constitute a legal obligation for employment. Any changes in business conditions (mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, etc.) could cause a job offer to be rescinded.

The last word Derrick heard from the HR representative after his final interview was, “We are good to go with an offer of employment.” He jumped the gun and resigned from his old company right away. That night, he was dismayed by the call from that same HR rep, who informed him, “Something came up and there will be a delay in getting that offer letter to you.” Eventually, it worked out, but he had to go through a couple of uncomfortable days, having resigned from his former company without confirmation of a job offer from another.

Also, read your offer letter carefully. It probably contains all sorts of qualifiers about not intending to create an “implied” contract. Employment lawyers routinely advise companies to limit their offer letters to start date and salary. As a result, details about other conditions of employment may be intentionally omitted. Most companies are willing to go further, but the language they use will in all likelihood be approved by legal counsel.

Since many offer letters are carefully scripted to give the advantage to the company in the event a dispute arises, you should have your offer for more senior-level positions reviewed by counsel as well, especially if you have negotiated any exceptions to the company’s general policy. Companies usually reserve the right to rescind offers if business conditions warrant, and from time to time that happens. An offer in writing confirms the company’s commitment to all the details necessary to move forward.

In certain cases, negotiated conditions of employment are complicated, and a written offer letter gives you an opportunity to clarify any commitments before it is too late to do anything about them. Plus, you have additional time to review your list of “must-haves” and determine if the new job includes all of them. If not, you still have time to revisit the details of the offer and have them adjusted.

4. KNOW HOW YOU STACK UP AGAINST THE COMPETITION

If you are the only viable candidate for the position, your bargaining position is much stronger than if you are one of several possible candidates. Gaining access to that information may be difficult, however, and you should plan to conduct your negotiation without it. At critical times during your interviews you might be able to get a strong indication of what the company’s situation is. For example, you are likely to have more bargaining power if the job for which you are interviewing is considered critical and has been vacant for a long time. Those extreme cases are easy to decipher. One way to dig out the information is to ask questions about how long the job has been open and how critical it is to running the organization. Obviously, such questions are less appropriate for lower-level positions.

5. UNDERPLAY YOUR HAND

Some people pride themselves on never leaving a dime on the negotiating table. That strategy is a mistake because it forces you to haggle over issues that are relatively unimportant. Your list of priorities is, in part, designed to help make distinctions among what you must have and what it’d be nice to have.

Ed was a haggler by nature, and he did not draw up a list of priorities beforehand. As a result he argued each item in his negotiation as if all were of equal importance. The hole he dug became deeper and deeper. The hiring manager started to wonder if the skills Ed brought to the company were worth the hassle. The company did not like what they saw when Ed did not get his way.

Lower-priority items provide a good way to make gracious negotiating concessions. They show that you are willing to see the other side of an issue and accept someone else’s best thinking. You give up an item on your list to foster an image of being a reasonable employee. In this sense, you have underplayed your hand and did not get all you bargained for. But you also demonstrated a willingness to compromise for a larger good.

6. UNDERPROMISE AND OVERDELIVER

During negotiations, you must make a major mind shift in how you approach the process. Until now, you have emphasized all the wonderful things you have accomplished and the match of these accomplishments to the requirements of the job. Once a job offer is in hand, most candidates continue to charge ahead, perhaps promising more than they can deliver in the time frame others ask. That’s a mistake—a major mistake. It is now time to change gears.

Expectations help shape how your performance on the job will be perceived. An example from the world of customer service demonstrates this point. At a bank in Westchester County, New York, wait times at bank branches was an important customer-service issue. Customer complaints grew in proportion to the wait times. A debate ensued as to the best way to improve customer service. As an experiment, the wait time in one branch was reduced from nine to six minutes during peak hours of branch usage by adding additional staff—an expensive solution. In another branch (the one it took the staff from), wait times went from nine to twelve minutes. But to alert customers to the prospect of longer waits, an electronic display of “anticipated wait time until the next teller is available” was adjusted to a time that was always greater than the actual wait.

What was the result? Customer satisfaction in the branch with longer wait times rose dramatically. At the same time, it remained the same for the branch with lower wait times. Bank management concluded that the newly created expectations led to the “appearance” of better customer service and to greater customer satisfaction, even though the wait times were actually longer.

The same principle is at work when you start a new job. New employees have a tendency to make exaggerated promises about what they can do and how quickly they can do it. Yet research clearly proves that overpromising and underdelivering is a significant factor in determining poor performance and is a significant cause of new executive terminations.

It is better to set expectations you can exceed than ones you can’t possibly meet. Once an offer is made, and as you are asked to make performance commitments, tone down your eagerness to demonstrate a “can-do” attitude and make measured promises about your performance. Then deliver ahead of schedule. A few times of exceeding expectations will help create a positive perception of how well you are doing.

7. NEVER END THE NEGOTIATING GAME

Well-run companies treat high-performing employees better than other employees. And high-performing employees are perceived as the ones who create value. An important part of any job is to continue to create value for your employer in the same way as you positioned your skills when you first applied. You should from time to time review the position description and the résumé you tweaked for it. The alignment between the two documents represents the value the company looked to create when it filled the position. Your new job is to create that value or its equivalent, over and over again.

There will always be circumstances beyond your control and jobs will continue to be eliminated regardless of how much value you create. But the unyielding focus on value creation lays the groundwork for your next job search. That focus can put you in the category of people who find new jobs rather easily and cause other people to wonder what you know that they don’t.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Your next job is always right around the corner. Sometimes that’s because your current one has been eliminated and/or because you consciously choose to do something different. The skills and information you need to make that choice is the subject of the next chapter.

NOTE

1. Chester L. Karrass, In Business as in Life, You Don’t Get What You Deserve, You Get What You Negotiate (Stanford Street Press, 1996).