So far we have focused solely on creating HTML emails. By now you have all the information you need to be able to think through a design and then build it into a working template.

In this chapter we will be taking a broader look at the business side of commercial email, to understand what should and should not be sent, and who should be receiving it.

You might think that managing permission is outside your job description, that you can just do the design and hand it over to your client. In some situations, that may well be true. But even so, there’s a huge need for designers to understand the legal, practical, and ethical issues around email marketing.

Why should you care? Pragmatically, if you offer email newsletters as a service to your clients or your employer, you should be able to explain the laws, limits, and best practices of the industry. It will prevent them from running into problems, thereby making your advice and services more valuable.

On a personal level, we should all care about permission because we all receive commercial emails, and not always by choice. Too many people send unwanted email with the help of designers who never bothered to check who the subscribers were going to be.

Finally, you need to know about permission so that you stay on the right side of the law and avoid any legal problems. So, now that I’ve convinced you of the need to care about permission, let’s ask an even more fundamental question: what is permission anyway?

My first rule of spam is that any email that contains the phrase “this is not spam” is almost always spam. My second rule of spam is that nobody thinks that what they’re sending is spam.

Of course, this is a massive oversimplification. Obviously some people really are unrepentant spammers who know exactly what they’re doing, but many more senders are convinced that what they’re doing is not spam, while their recipients think otherwise.

As designers, we obviously need to avoid sending emails that are considered spam by the law. But it’s an often-ignored fact that we should also avoid sending emails that are perceived as spam. We’ll look into that in a moment, but first we’ll start with the broadest and most widely accepted definitions of what constitutes spam: the legal definitions. In fact, there’s a whole slew of legal definitions, depending on where you’re based. The most well-known of these laws, which we touched on in the section called “Legal Compliance” in Chapter 3, is the US CAN-SPAM Act.

If you’re sending email as a US company (or for a US company), you’re legally bound to comply with the CAN-SPAM laws. For the full details on your obligations, see http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/edu/pubs/business/ecommerce/bus61.shtm.

Here are the core requirements, directly from the Federal Trade Commission, the principal US consumer protection agency:

- Don’t use false or misleading header information

-

The From, Reply To, and other address details should all be valid and accurate for the sender and recipient.

- Don’t use deceptive subject lines

-

The subject line should accurately reflect the content of the email.

- Identify the message as an advertisement

-

Don’t try to disguise it as a personal email, for example. This law indicates why you sometimes see [ADV] in subject lines.

- Tell recipients where you’re located

-

Include a valid, physical postal address for the sender.

- Provide a way to opt out

-

You must include a clear, prominent way to opt out of future email (which can be automated or manual).

- Honor opt-out requests promptly

-

You must give people a way to opt out that’s available for at least 30 days after you send them the email, and you must act on a request to opt out within ten business days, for free. An online opt-out must only require sending a single email, or visiting a single page.

Clients are unable give us as designers the sole legal burden of complying with these laws; instead, we’re jointly responsible for meeting them.

These are the guidelines as of February 2010, but keep in mind that the FTC has made additional rulings since first issuing the laws, so you need to keep an eye out for any future updates.

Many countries have published their own laws regarding spam and commercial email.[6]

Wherever you live, you need to know the legal issues for you and your clients or company. However, complying with the law is just part of the equation; there are other issues with which to contend.

What the law considers to be spam is often quite distinct (and much narrower) than what the typical email reader considers spam. As a consequence, what an ISP or an email service provider considers spam will often include a lot more than what the laws cover.

Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson of the opinionated web application firm 37signals make this point in Rework (New York: Crown Business, 2010):

Spam is a way of thinking. It’s an impersonal, imprecise, inexact approach. You’re merely throwing something against the wall to see if it sticks. You’re harassing thousands of people hoping that a couple will respond. Press releases are spam. Each one is a generic pitch for coverage sent out to hundreds of journalists you don’t know hoping that one will write about you. Resumés are spam when someone shotguns out hundreds at a time to potential employers. They don’t care about landing your job, they just care about landing any job. Spam is basically a half-ass way of getting someone’s attention. It’s insulting, really.

Legally speaking, press releases and resumés are not spam, but the authors of the book consider those kinds of email to be just as spammy as Viagra or mail-order bridal offers. This is a redefinition of spam to extend beyond emails I didn’t ask for to also include emails that are irrelevant or worthless.

A 2008 survey by Q Interactive and MarketingSherpa has confirmed that this is a growing definition for individuals as well:

Underscoring consumers’ varying definitions of spam, respondents cited a variety of non-permission-based reasons for hitting the spam button, including “the email was not of interest to me” (41 percent), “I receive too much email from the sender” (25 percent), and “I receive too much email from all senders” (20 percent).

From an email sender’s perspective, this can seem unfair. You gather permission according to all the relevant laws, but are still labeled a spammer. Features like the Hotmail unsubscribe button can make it easier for people to achieve the result they want (less email) without having to accuse a sender of spamming; until this type of feature becomes more common, though, the spam button will continue to serve as a proxy for “I don’t want your emails.”

Email providers and ISPs have publicly admitted to using the same kind of judgment in deciding what counts as email abuse:

Operationally, we define spam as whatever consumers don’t want in their inbox. | ||

| --Yahoo Mail (Miles Libbey, anti-spam product manager) | ||

I don’t care if they’ve triple opted-in and [given] you their credit card number … relevance rules, and catering to end user preferences is top priority. | ||

| --AOL (Charles Stiles, AOL Postmaster) | ||

We need to think really a step beyond opt-in and focus on the consumer’s expectations, relevancy, and frequency. | ||

| --Microsoft/Hotmail (Craig Spiezle, online safety evangelist) | ||

You need more than just permission; you also need to put yourself in your subscribers’ shoes. They signed up for information about one of your products, but does that mean they want to be emailed about your other products? Not necessarily.

You’ve worked with your client or team to determine that you can legally send to subscribers, but there’s still work to do. Now you’re into the gray area of interest, relevance, and potentially “stale” permission.

There’s no way to guarantee that someone, somewhere won’t consider any particular email to be spam. In fact, those in the tech industry are the most likely to make blanket statements about all marketing emails being spam, or even all HTML emails.

It’s just impossible to make everyone happy, especially those who somehow believe that banning HTML would eradicate spam (instead of creating more plain text spam, which is what would happen). So, what to do?

The best way to avoid being blocked, deleted, flagged, junked, or just plain ignored is to work very hard at making your emails relevant, usable, and useful. That means providing the information you promised when people signed up, and not taking the permission granted for one type of information and stretching it out to cover other topics.

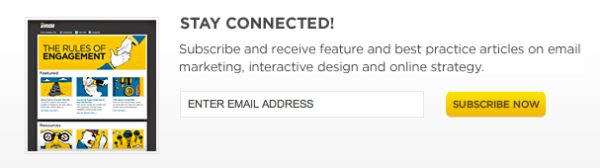

Practically, this means being clear about why people should sign up, and then providing those benefits consistently. As designers, we can take this all the way from the initial sign-up form. Compare the two sign-up forms shown in Figure 5.1 and Figure 5.2.

Even before any email is sent, each form has created its distinct audience. People who signed up through the first form will be expecting a newsletter, yes, but what will it contain? What will it look like? How frequently will they receive it?

They could be imagining something quite different from what you actually intend to send. If it turns out to be unsatisfactory, they may simply unsubscribe. But they might also mark your email as spam. Subscribers to the second form will be expecting exactly what you intend to send, so they’ll know it when they see it, and they’re more likely to remember signing up for it.

Designing for relevance carries through to the content. You need to make sure that not only is the actual subject matter relevant, but that the design makes this clear by putting the valuable information up front, rather than burying it in unrelated promotions or cross-selling.

Providing timely and useful information is the best defense against spam complaints, not to mention apathy and indifference. After all, receiving no response at all can be even more disheartening than receiving complaints.

Even the cleanest, most permission-based of lists will probably result in a complaint or two eventually. Not every complaint is legitimate—some are accidentally triggered, and others are from readers who think that hitting “mark as spam” is the easiest way to unsubscribe. As we saw in the section called “Permission versus Spam”, many email software companies are actively encouraging this kind of behavior, so you need to know what it means and how to react.

Spam complaints come in a few forms, so knowing what they all are helps when trying to avoid them (as well as when dealing with the ones that are impossible to avoid).

Direct complaints are when a subscriber actively sends an email that says, literally, “This is spam” or calls on the phone. The complaint might come directly to you or to your client, or to your email service provider, or even to the ISP that provides bandwidth for the servers that send the emails.

Some ISPs and email providers (Comcast and Hotmail are two examples) have special systems set up that can collect complaints from their users and forward them on in a specific format to the email service provider that send the emails.

The service provider then receives those complaints and processes them according to its company policy. In the case of Campaign Monitor, the recipient is automatically unsubscribed, and a record is added to the sender’s campaign report showing that a complaint was made. This is fairly typical of the way feedback loop complaints are handled.

Feedback loops are almost always triggered by direct action (that is, a reader clicking a “Mark as spam” button or similar) rather than by an automated filter process. So the end result is much the same as a direct complaint, except that it can more easily be acted on, since it’s in a format that can be actioned by an automated software process.

If you choose to use an email service provider, you can check with them as to whether they’re integrated with feedback loops. While it might seem risky to open yourself up to such direct complaints, it’s better to handle them right away than find out that you’ve been blacklisted later on.[7]

Some email systems will generate warnings and complaints when they detect a certain volume or frequency of emails that are considered possible spam. Generally those will be sent to your email service provider rather than directly to you as the sender, but your email service provider would then follow up with you.

In all cases, being able to show how permission was obtained for any particular subscriber is critical. A fast, detailed response to a complaint that provides permission details and offers to unsubscribe the address will usually avoid any ongoing problems.

Clients often feel understandably defensive about their lists and can be tempted to respond aggressively, but it’s important to make them understand that this kind of response is counterproductive. Although some complaints may well be unfair, email providers have to take each one seriously, so it pays to be prepared with evidence of an email list that’s fully permission-based.

Keeping a record of who has complained is essential, in order to avoid emailing them again. Some email systems will do this for you, and you should find out if that’s the case for your provider.

Above all, spam complaints are valuable feedback and should be accepted as your recipients letting you know something about your list. By reading their minds a little, we can interpret a simple spam complaint in different ways:

- “I don’t remember signing up for this.”

-

How long ago did the people on your list sign up? It could be that the span of time between signing up and receiving an email was too long, or that the sign-up form was unclear about how frequent the emails would be.

- “I did not agree to these emails.”

-

Was the opt-in process very clear? A common cause of complaints is forcing people to join your list as part of entering a competition. Both the sign-up form and the emails themselves need to be extremely clear about what’s happening. If a reader signed up to win a prize, but the first email makes no mention of the competition at all, they’re much more likely to consider it spam.

- “This is not useful information.”

-

Perhaps the content of the email isn’t what was promised. Don’t promise useful hints and tips and then send promotional junk every month.

- “I don’t care about this anymore.”

-

Maybe the reader just moved on and no longer has a need for your product or service. The spam complaint might mean they don’t want to receive your emails anymore and thought hitting “Mark as spam” was the best way to achieve it.

- “I can’t be bothered to unsubscribe.”

-

Related to the previous point. As I’ve already mentioned, making the unsubscribe link hard to find is self-defeating. If your reader doesn’t want any more emails, don’t try to trick them into staying on your list. Put a simple and clear unsubscribe link right up front, and avoid forcing people to complain.

Any email newsletter service you use will have their own spam complaint process, which you’ll need to know about and explain to clients. Most people never run into serious complaints, but it can happen and you do need to be prepared.

There isn’t any one number that you can rely on. Every email service will have their own “safe” level, but even one complaint can cause problems if it reveals that permission was not obtained properly.

In practice, there’s always a “normal” level of complaints, appearing like background radiation no matter what you do. That number is typically very low, around 0.01%. If your campaigns are receiving complaints at around that frequency, there’s no need to be too concerned.

Obviously, if you’re dealing with very small lists one complaint can be a big percentage, so in order to gain an accurate view you’ll need to average it out over a number of campaigns.

Again, check with the system you use to email, or with your ISP, as to what they consider to be a bad number of complaints.

When you’re sending your own campaigns, you have all the information you need to know whether your list is permission-based, and what kind of emails the people on the list will be expecting. When it comes to dealing with clients, however, it can be a little bit trickier.

You can ask them to read the permission rules that apply for your chosen email service, but how can you know if they’re giving you all the information? There are a few guidelines for exploring how permission was obtained that should help avoid unpleasant surprises after sending.

Don’t settle for a simple “yes, this list is fine.” Ask more detailed questions, such as “Can you give me a list of the different ways people can make it onto this list, like forms on your website, or signing up in person or by email?”

This will make your client think in more depth about how the list was constructed, and may bring up some new information.

If you’ve asked your client whether they followed all the relevant guidelines, and they say that they have but you’re still concerned, seek a direct confirmation.

“Just to confirm, all 955 of these people signed up on your website. You didn’t add anyone at all?” If they’ve any doubts or have forgotten other ways, this could help them remember.

See if the email content makes sense in the context of how the list was supposedly gathered. If your client is telling you that their list is made up customers who’ve recently bought a certain product, but their email copy directly promotes that same product, that’s a sign you should ask a few more questions.

Most people think that their entire subscriber list will be ecstatic to hear from them. Clients often won’t realize that there are risks for them in sending to a list that isn’t permission-based. If they receive spam complaints, but they do have explicit permission from each person they emailed, then it can be resolved. On the other hand, if they receive complaints from people who fall outside the legal or commercial criteria for having given permission, their account could be closed or they could be blacklisted.

Going through this process with your clients can be annoying, but it will protect their reputation—and also your own—if complaints do start to come in. If your client is sending from their own servers or from a dedicated IP address, blacklists are also a concern.

Due to years of abuse from deliberate spammers, hundreds of services have popped up to deal with this problem. If you’re using an external provider, they’ll generally take care of ensuring that their emails bypass these anti-spam services.

If you’re using your own servers, your client’s servers, or a dedicated external server, the task will fall to your client and their consultants to handle it. Such details fall outside the scope of this book, but having a good understanding of what blacklists are and how they work will help with planning and implementing your email campaigns.

In the email world, a blacklist (also called DNSBL for DNS Based Black List) is a list of IP addresses that are linked in some way to spam. Anti-spam software and mail servers can refer to this list of addresses when receiving mail, to decide whether to allow it to be delivered. Blacklists can form a part, or the whole, of the process of filtering an email.

If the server you use to send email is listed on a major blacklist, your emails may be more heavily filtered, or be blocked altogether. A major part of an email service provider’s value is in monitoring these lists and making sure that their IP addresses remain off blacklists.

Inevitably, legitimate servers will be listed (perhaps because of inaccurate complaints), but a good email service will follow up and usually be delisted fairly quickly. If your client wants to handle sending the emails themselves, or wants you to handle it, you should make them aware of the amount of work that can be involved in managing this part of the equation.

To find out if a particular IP address is listed, you can go directly to a specific list provider. Alternatively, you can use one of the aggregator tools, such as DNSBL.info, and enter the IP address there.

Where a blacklist works by letting all email past except for mail from specific IPs, a whitelist takes the opposite approach and blocks everything by default. Only email from a specified set of IP addresses is allowed past.

Historically, some of the large email providers did have systems for whitelisting known senders, but this approach is becoming increasingly rare as they move to reputation-based systems that measure complaints, volume of sends, bounces, and the like. If your client is having problems reaching a particular domain, especially if it belongs to a smaller company, requesting to be added to the domain’s whitelist can often resolve the problem.

Overall, this kind of list-based spam system is only a small part of the email game. If we all concentrate on sending relevant, useful information that people have actually requested, we’ll be in the best position to have our emails delivered in the long term.

While both blacklists and whitelists are declining in relevance and importance, sender reputation is rapidly becoming the key way of ensuring emails are delivered. Organizations like Return Path provide a service that ranks email senders according to a combination of metrics mixed into a single score that represents the reputation of the sender.

Email administrators and providers can use that rating in their filtering when deciding if an email is legitimate. According to Ken Takahashi of Return Path, the following elements make up a sender reputation:

-

the volume of email you send (and how consistent that volume is)

-

the number and percentage of bounces your emails receive

-

the rate of complaints

-

whether you’re emailing known spam trap addresses (email addresses specifically set up just to catch spam, and never opted into or signed up for anything)

-

longevity of business (how long you’ve been sending)

-

infrastructure (whether you have all the capabilities to handle authentication, bounces, unsubscribes, and the like)

Looking at this list, it’s clear that a quality email service provider is well worth the cost, as there’s a lot of work in maintaining a system that deals with all those areas.[8]

In this chapter, we’ve used the word “permission” to refer to an individual opting in to receive emails from a person or business. There’s also another definition of permission in email, and that is at the mail server level.

Authentication is a way for a domain owner to say, “I give my permission for emails to be sent on my behalf by this mail server.”

Because of the way email was originally built, it’s difficult to prove that an email is actually coming from the person who claims to be sending it. Email authentication fixes this by letting you add some simple information to your domain’s DNS records that define who’s allowed to send email on your behalf.

Without going into too much detail, there are two main authentication standards: Sender ID and DomainKeys/DKIM. Different ISPs use either or a combination of both, so to achieve the best results you would want to implement them both.

All the large ISPs like AOL, Hotmail, Yahoo, and Gmail are using email authentication as an important layer in deciding whether to allow an email to be delivered. By using authentication, you can instantly bypass some filters, giving your campaigns a better chance of arriving in the destination inbox.

Not only that, but many ISPs, such as Yahoo and Hotmail, will visually flag your email as authenticated, which helps to build trust between you and your subscribers, improving the chances of your emails being opened. To implement it, you’ll need access to the DNS for the sending domain, so it’s unfeasible if you want to apply it to your client’s hotmail.com address. For a corporate domain, adding authentication records (normally given to you by your email service provider) is a great idea.

As of 2010, your email should still be delivered even if you are not using authentication, but there are signs that this could happen down the road, so it’s worth investigating now.

We’ve gone through a whole chapter and barely once mentioned HTML or CSS, but understanding permission is just as important as your ability to design and build emails.

Every time you take on a new HTML email design job, you need to understand who the audience is, how they agreed to receive the email, and what benefit they’ll derive from it. Avoid the temptation of leaving it until the last minute, because the consequences can be widespread and quite serious.

[6] For a list of relevant laws, see http://www.email-marketing-reports.com/canspam/.

[7] You can find a list of the major feedback loops at http://blog.deliverability.com/feedback.html.

[8] A great resource for understanding how sender reputation impacts on deliverability and permission can be found at http://www.email-marketing-reports.com/deliverability/.