Chapter 18

Making Regulators More Tech-Elite

During the BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill in 2010, U.S. Secretary of Energy Steven Chu blogged, “My job has been to oversee the federal science team—a group of top scientists from the Department of Energy's national labs, the federal government, and academia, along with outside industry experts. . . .”1

Around the same time, as the U.S. Department of Transportation was investigating multiple occurrences of sudden acceleration in Toyota vehicles, it announced it had brought in NASA engineers to help. The NASA charter was to determine “if there are design and implementation vulnerabilities in the Toyota Electronic Throttle Control System Intelligent (ETCS-i) that could cause UAs (unintended accelerations) and whether those vulnerabilities, if substantiated, could realistically occur in consumers’ use of these vehicles.”

The NASA team reported after its analysis:

Because proof that the ETCS-i caused the reported UAs was not found does not mean it could not occur. However, the testing and analysis described in this report did not find that TMC ETCS-i electronics are a likely cause of large throttle openings as described in the VOQs (Vehicle Owners’ Questionnaire).2

In an interview, Secretary Chu explained the reason for the large brain trust during the BP spill:

After the [Space Shuttle] Challenger accident, the U.S. government formed a panel of very, very bright scientists and engineers to come together and figure out what happened and what could be done in the future to prevent it. Most of the people on that panel were not aeronautics experts, not rocket experts or NASA experts. They were very smart people who had a broad range of knowledge and experience. This is actually what you want: you want a set of fresh eyes, people who can propose potential out-of-the-box solutions, who might foresee what might go wrong. If you're an expert and you're used to certain things done certain ways, that limits your ability to cast a wider net, and so one of the most important things that we're doing at the national laboratories is putting together these scientific teams, many of whom would be considered nonexperts. In times like this, those are many of the people you want.3

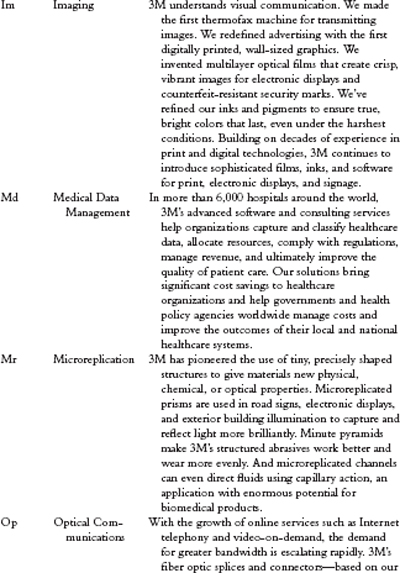

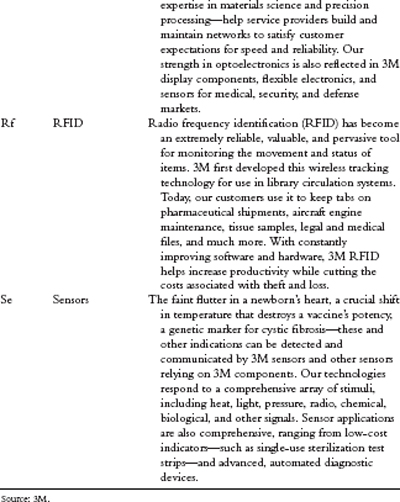

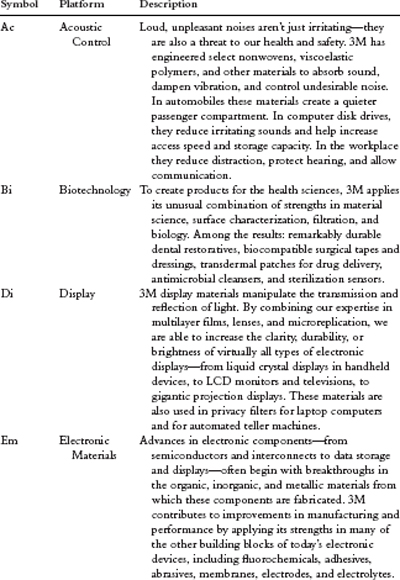

Rocket scientists helping on auto investigations, nuclear physicists helping on ocean-based investigations, and a multitude of other specialists helping with rocket science. We saw glimpses of government efficiency and innovation in earlier chapters with the examples of the country of Estonia, the Hillsborough County Tax Collectors Office, and Roosevelt Island. Overall, though, it is becoming clear that technology is stretching the capabilities of regulators. The range of technical skills we need in our regulators becomes very apparent when you look at the 3M Periodic Table we present in the case study with its 46 “technology platforms” from Biotechnology to Optical Communications.

Regulatory Challenges Galore

If there is a poster child for an agency that is overwhelmed by technology advances, it is the U.S. Patent Office. Even though a quarter of patent applications come from California, it does not have a branch office there. The Office is so backed up that applications don't get looked at for years. It is not uncommon for patents to take three to five years to get issued. Until recently, the Office, which should be tech savvy itself, would not accept digital applications.

Then, as we saw in Chapter 14, interpretation of those patents is even more convoluted, leading to many legal battles. Google's chief lawyer Kent Walker has been quoted as saying the smartphone industry is using patents in an arms race that is “gumming up the works of innovation.”4

Indeed, one of the major reasons Google bid $12.5 billion to acquire Motorola Mobility was its vault of 17,000 patents and another 7,500 in progress.

Commented Rafe Needleman: “The accumulation of patent portfolios into a smaller number of bigger players, which themselves are locked in a deadly standoff, has the real potential to slow down the pace of innovation. Which is precisely the opposite reason the patent system was created.”5

It is estimated that over 200,000 emergency 911 calls are placed daily in the United States via mobile phones, and even though the phones can relay GPS locations, the 911 centers have to ask for specific location information, when the caller is likely under extreme stress. Additionally, VoIP lines have been replacing landlines in countless homes and businesses for over a decade now. Yet, it's only in 2011 that the FCC has announced plans for Next-Generation 911, “seamless, end-to-end IP-based communication of emergency-related voice, text, data, photos, and video between the public and public safety answering points.”

There are many examples of inadequate regulation in the financial sector. The New Yorker summarized:

Financial regulators let A.I.G. write more than half a trillion dollars of credit-default protection without making a noise. The S.E.C. failed to spot the frauds at Enron and WorldCom, gave Bernie Madoff a clean bill of health, and decided to let Wall Street investment banks take on obscene amounts of leverage, while other regulators ignored myriad signs of fraud and recklessness in the subprime-mortgage market.6

Frank Scavo, who runs Computer Economics, says,

We've been benchmarking IT organizations since 1990, so we have quite a bit of information on historical IT spending trends. Based on our data, we know that financial services organizations are among the most IT-intensive industries, no matter how you measure it. For example, this year, the typical commercial bank is spending 6 to 7 percent of its revenue on IT. In contrast, the typical manufacturing company only spends 1 to 2 percent of its revenues on IT. This is because banks, insurance companies, and other financial institutions are really information businesses. On the surface, they are developing, marketing, and selling financial services. At their core, their business is all about leveraging information for financial gain.

Do the regulatory authorities have the skills and systems to oversee these institutions? After the last financial crisis, you have to wonder.

Life sciences are another sector that is very IT-intensive. According to our research, the typical life sciences organization today spends 4 to 5 percent of its revenue on IT, and this doesn't include all the technology investments taking place outside of the traditional IT organization. For example, most high-end medical devices, such as diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy equipment, are really smart devices in every sense. They process large amounts of information and are increasingly being connected to hospital networks. At the other end of the spectrum, small start-ups are figuring out how to use smartphones to displace low-end medical devices, such as stethoscopes, blood pressure monitors, and glucose testers. You can even buy apps like these on iTunes for a few dollars.

Do regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have the resources to ensure such devices are safe and effective? To the FDA's credit, it has indicated that it does not want to stand in the way of technology adoption. But whether it has adequate technical staff to review these new products coming to market is another question.

Mark Cuban, described in earlier chapters, is much more direct about what financial regulators should be doing:

[They] have got to start to recognize that traders are not investors and vice versa and treat them differently. Different regulations. Different tax structure. Different oversight.7

Not Just U.S. Regulators

The head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has acknowledged that he would like to see his agency more involved in damage control from any future nuclear disaster. These were comments prompted by criticism of the IAEA's role in the Fukushima accident after the Japanese earthquake and tsunami in early 2011. “The IAEA itself will acknowledge privately that it did not cover itself in glory,” says James Acton, who studies nuclear policy at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, DC.8

The Air France 447 crash off the Brazilian coast in 2009 raised a number of regulatory issues. The icing of Thales AA pitot tubes, which help calculate airspeed, had been shown to be a regular problem and yet “Regulators simply asked Airbus to watch the problem and report back in a year.” In our days of streaming TV and music, why do planes still store critical data on old technology called black boxes? In the case of the Air France flight, it took over two years to recover the black box from the bottom of the ocean. As a New York Times article suggested, we should be aiming for at least partial data streaming directly from the plane during events like failure of the autopilot.9

In July 2011, a report by the UK Public Administration Select Committee (PASC) of the UK House of Commons said, “The Government's over-reliance on large contractors for its IT needs combined with a lack of in-house skills is a ‘recipe for rip-offs.’ The committee found that as a result IT procurement too often resulted in late, over-budget IT systems that are not fit for purpose.”10

The Shifting Winds

Robert Hoffman has more than two decades of policymaking experience in Washington, including 11 years as a legislative aide and director in the U.S. Senate. He also has more than a decade of experience as a public policy manager and advocate for Oracle Corporation and Cognizant Technology Solutions.

He summarizes trends in technology oversight in Washington:

The U.S. federal government has long struggled with regulating information technology. U.S. state governments and the European Union have become comfortable playing the role of IT consumer advocate, and strictly defining the responsibilities and requirements of IT developers, vendors, and users on how sensitive personal information is stored. For nearly two decades, Washington has hesitated diving so confidently into the IT regulatory pool.

Even when the horror of 9/11 brought even more compelling arguments for tighter government regulation of crypto-products and IT systems, Washington again hesitated. It wasn't just the threat of a mass exodus of high-technology and high-paying jobs that prompted Washington to hesitate. Legislators and regulators did not have a firm grasp of the technology landscape itself. Sending emails or surfing websites constituted the extent of a legislator's or regulator's exposure to technology. Indeed, the most tech-savvy people on Capitol Hill in the 1990s were overwhelmingly the young twentysomethings that wired-up the fledgling client-server operations and programmed the first mobile phones in each congressional office. If there were dominant regulatory arenas that the IT industry had to confront in Washington over the past two decades, they were antitrust and export controls. After all, policymakers may not fully understand technology itself, but they could easily conclude that too much of something in the hands of one or a few, whether that something was soft drinks or software, can't be good for the U.S. economy. Similarly, they understood state-of-the-art technology may be good for financial institutions, but not foreign terrorists.

Hoffman continues with a focus on today:

So, fast-forward to 2011, and let's review the key policy and regulatory issues that are on the IT policy agenda: cyber-security, data privacy, data breach reporting requirements, standards for critical infrastructure protection, and Internet neutrality. Today, there is no one federal department or agency that has singular regulatory authority over IT, and those that could assert such authority won't do so without clear congressional authorization.

For DC veterans, this agenda has a familiar ring. Indeed, almost all of today's issues and regulatory challenges were on the agenda in 2001. The technologies certainly have advanced, but the issues have marked time and could not be resolved. This is due to many of the same reasons that influenced the encryption debate: the fear of stifling innovation, an uncertainty about the underlying technology itself, and competing points of view from within the sector, which suggested that policy solutions would effectively distort the market by picking winners and losers. When it comes to managing IT policy, it's been Groundhog Day for well over a decade in Washington.

Hoffman on likely changes:

I don't see that lasting for much longer. For the next two to three years, regulators and policymakers are likely to achieve more regulatory authority and policy certainty over the IT industry than ever before. True, given the past track record, that won't be hard, but several fundamental factors are working to create an environment where legislators and regulators will look at IT policy with greater creativity and confidence. Those factors are:

- Tech-savvy policymakers are coming of age. The twentysomethings that first connected Capitol Hill to the information superhighway are now in positions of authority—on the Hill, in regulatory bodies, in trade associations, and in industry. They are showing nimbleness in response to the emerging trends in IT, ranging from mobility to social media to cloud computing. Yes, the IT industry is still a young person's sector, but there isn't the kind of generation/knowledge gap between IT and DC that we witnessed in the 1990s.

- The federal government is becoming not just a major IT user, but a better IT manager. At roughly $80 billion per year, the federal government is the single largest buyer of technology in the United States, but only in recent years has it decided to manage its IT infrastructure in ways that the private sector has done for years. It appointed its first-ever CIO, who pursued much-needed reforms to consolidate servers, and provide greater transparency in IT management. The challenges and uncertainties public agencies face about managing IT systems in a cloud environment are the same as those faced by private sector firms.

- As the federal agencies become better IT managers, they are certain to change the dynamic of the federal government's relationship with the private sector. Standards to protect critical infrastructures, methods to respond to emerging cyber threats, and data privacy are clearly areas of mutual concern to private and public sectors. That would suggest that a more collaborative public IT manager-to-private IT manager approach to respond to these issues would be a compelling option for governance, rather than a traditional, mandate-driven public regulator-private regulatee approach.

Hoffman summarizes:

One of the challenges for the federal government, as its agencies continue to better manage IT infrastructures and be responsive to new trends, is whether it can reconcile and integrate these dual roles of manager and regulator of IT. Are the agency regulators talking to the agency's CIOs, CSOs and CPOs, and vice versa? Such intra- and interagency collaboration is likely to make the federal government better at both managing and regulating IT, while staying true to the long-standing principle of promoting IT innovation and doing no harm.

Conclusion

The regulation of technology is going through significant change. This is causing the technology elite to evolve how they interact with regulators and other market watchers. The 3M “Periodic Table,” described in the following case study, is what market watchers will increasingly have to be intimately familiar with.

Case Study: 3M's “Periodic Table”

3M, a company founded in 1902, is a remarkably diversified entity. David Meline, its CFO, broke out the $ 27 billion in 2010 revenues at an investor conference in June 2011. They were distributed across industry sectors: 32 percent from Industrial and Transportation sectors, 17 percent from Healthcare, 14 percent from Consumer and Office, 14 percent from Displays and Graphics, 12 percent from Safety, Security, and Protection Services, and 11 percent from Electronics and Communications.

Geographically, it got 35 percent of revenues from the United States, 23 percent from Europe, 31 percent from Asia Pacific, and 11 percent from Latin America.

As Meline got to slide 14, he presented a table similar to one we studied in Chemistry class. But instead of H for hydrogen and Au for Gold it showed 46 3M “technology platforms”—Bi for Biotechnology, Op for Optical Communications, and so on. 3M innovates by finding “uncommon connections” of these platforms to create unique solutions for customers across all six of their focus industry sectors shown above.

From slide 15 on, he was back presenting financial numbers.

That one slide though, drove home 3M's amazing technology diversity. 3M is fundamentally a science-based company. With more than 55,000 products, 3M continues to demonstrate an uncanny ability to combine highly innovative technologies in new and unexpected ways.

It is a remarkable turnaround for a company with a “star-crossed” beginning as described in its history published on its 100th birthday. It detailed:

First, a worthless mineral, then virtually no sales, poor product quality, and formidable competition. All the founders had to keep them going was perseverance, a spirit of survival and optimism. What would happen next? It was the equivalent of the sky falling, only at ground level. 3M built its new plant, a two-story, 85-foot-by-165-foot structure with a basement. It wasn't the best construction, but it was all the budget allowed. When raw materials arrived from Duluth and were stacked on the first floor, one Saturday, the weight tested the timbers—and the timbers lost. The floor of the new plant collapsed and every carton, bag, and container landed in a heap in the basement.

Table 18.1 3M's “Periodic Table”

How does a company so diverse communicate with its customers and market watchers? One creative way has been to present its “Periodic Table” on its website, allowing viewers to drill into each platform.

Table 18.1 extracts 10 of those platforms, and you can see the breadth of markets it supplies technology products and components. This shows less than a quarter of its platforms.