CHAPTER ELEVEN

EVERY DAY IN EVERY WAY, WE GET A LITTLE BETTER

Recruiting people to join your startup is essentially a sales pitch: you're convincing people to sign up for your dream. It's all flowers and chocolates. And while there's a crucial educational component to successful onboarding, it also involves more selling and evangelism for your cause. The hard part comes later, when you have to solicit and provide feedback on performance or fit (this is even more difficult).

Even the most self-aware and self-possessed among us don't like being told that we're not doing a good job, no matter how much positive feedback we might also be hearing. Communicating criticism is a necessary component of providing honest feedback. It's uncomfortable. It can lead to tears and firings and resignations, but it's the most important thing you can do as a CEO, both for yourself and for your team.

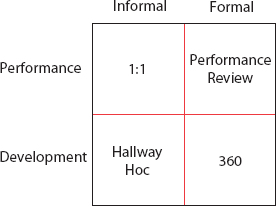

There is a variety of ways to give and receive feedback, but I've found it useful to divide all of them into a simple 2 × 2 matrix: informal 1:1s, formal performance reviews, ad hoc hallway chats, and annual 360s.

THE FEEDBACK MATRIX

There are many different opportunities for giving an employee feedback, and there are many types of feedback that you can give. To clarify things, it's helpful to reduce this variety to a simple 2 × 2 matrix: The Feedback Matrix (shown in Figure 11.1).

FIGURE 11.1 Introducing the Feedback Matrix

Essentially, there are two types of feedback you can provide:

- Feedback about an employee's performance relative to their goals and objectives.

- Feedback about an employee's skill set, cultural fit, and way of getting things done.

You can deliver that feedback in one of two ways: formally or informally.

This matrix helps you be clear about what type of feedback you are providing (or soliciting) and what outcome you hope to achieve. It also serves another purpose: making the process of giving and receiving feedback more comfortable. Instilling a culture where feedback is wanted, expected, and doled out regularly is the best way to get over people's innate discomfort with feedback, and the feedback matrix helps provide that regularity. In addition to keeping you and your management team organized, it fosters a culture that values transparency; celebration (not all feedback is negative!); and honest, constructive criticism.

1:1 Check-ins

Informal 1:1 check-ins are a great way to take your team's pulse without creating an overly top-heavy (and intimidating) system of constant reviews. I find that these work best on a weekly basis, but the specific interval isn't important—as long as it's consistent. While it's important that you and your managers set the agenda for these meetings at a high level, the key to keeping them informal is allowing your reports to drive the specific content.

The standing agenda for 1:1s is simple. Each week, you and your reports will review goals, track progress against those goals (i.e., review metrics) and set short-term priorities. If your reports are managers themselves, you should also review those items with regard to the people they oversee.

By allowing your reports to drive these meetings, you're making it clear that you trust them with the responsibility of managing their own careers. In addition to setting the basic framework for these informal check-ins, there are two important functions you can perform: reacting with feedback, and providing organizational context. As CEO, you have a panoptic view of your company that nobody else in your organization shares. Your reports may simply be unaware of how their work complements—or conflicts with—other initiatives at your organization. This is your opportunity to fill them in.

“Hallway” Feedback

While informal performance reviews can be handled on a regular basis, informal feedback about other matters can take place anytime. This kind of feedback falls into two categories: quick corrections and congratulations.

On the negative side, there are behaviors that need to be corrected immediately: an employee has behaved in a way that violates your team's core values, alienates their colleagues, or has otherwise caused a problem. If matters like these aren't handled right away, they can poison your culture. It is essential that you (and your managers) not allow this to happen. On the positive side, if someone has done outstanding work, you want to recognize and reinforce that behavior as quickly and explicitly as possible. It only takes a minute, but employees tend to have long memories about positive feedback. As we've discussed, a culture of thankfulness is as essential to success as a culture of performance.

Even ad hoc processes have their best practices. The one I follow for these quick check-ins is from Ken Blanchard's book The One Minute Manager. To sum it up:

- Tell the person up front that feedback is coming.

- Give the feedback as soon as possible after the incident.

- Be specific.

- Stop for a few moments of silence.

- Shake hands at the end.

“Ad hoc” simply means that the meeting wasn't scheduled in advance. It doesn't mean that it should be sloppy and unproductive. The simple guidelines listed here will make it as high impact as your weekly check-ins.

Performance Reviews

Effort is important in life. Woody Allen says 80 percent of success in life is just showing up. If he's right, then perhaps 89 percent is in showing up and putting in good effort.

If you put forth a poor effort and still got to the right place, you got lucky. Ultimately, how you get something done is important. Wasting time or burning bridges with colleagues or clients along the way can have long-term negative consequences that outweigh any short-term gains. When all is said and done, results speak very loudly. Customers don't give you a lot of credit for trying hard if you're not effectively delivering a product or solving problems, and investors ultimately demand results.

Results can't be realistically gauged on a week-by-week basis, so they don't form a huge part of informal weekly performance reviews, but they should be central to the annual performance management process.

It's easy to overdo these processes. Don't. Keep them as short and lightweight as possible, and focus on the essential question: how are employees performing relative to their goals? For the annual performance review (as opposed to the comprehensive “360”), only two people should answer that question: managers and the employees themselves.

![]()

Every organization defines performance differently. If you communicate performance benchmarks clearly and frequently, employees should have no trouble evaluating themselves and others relative to those benchmarks. In other words, for each given area, whether employees are performing “At Standard,” exemplifying a “Best Practice,” or this is an “Area for Improvement.” (At Return Path, we used the abbreviations “RPS” [Return Path Standard], “BP” [Best Practice] and “AI” [Area for Improvement]. Some sample performance assessment forms are available at www.startuprev.com.) If it's either of the latter two, provide space for more detail. The actual performance review can then focus on two things: exceptions (areas where an employee is outstanding or lacking) and areas of disagreement, where employees and managers aren't aligned about what's going well and what isn't.

The 360

A 360 doesn't have to be live to be effective. As your organization grows, performing live 360s for every employee obviously won't be feasible. At Return Path, live 360s are limited to VP-level team members and above. For other employees, we take the same “full view,” but we do it with online forms. These include a self-assessment, an assessment by the employee's manager and any of their subordinates, and reviews from a handful of peers or other people in the company who work with the person. They're done anonymously, and they're used to craft employees' development plans for the next 12 months.

The live 360 review combines performance and development feedback into a single event. It's time consuming, but it produces fantastic results. This is how it works:

Before the live 360, the person being reviewed meets with an outside facilitator (such as an executive coach) and has an in-depth discussion. Potential questions for this discussion include:

- What were the critical incidents in the past year?

- What went well and what went poorly?

- Did you make progress against your prior year's development plan?

- What areas would you like specific feedback on?

The facilitator then joins a large group to lead another discussion. (At larger companies, this might just be the executive team or members of an employee's group. At early-stage startups, this could be the entire company.) The person being reviewed is not in the room. Sometimes a note taker will be present or the session will be recorded, which frees up the facilitator to engage in the discussion.

The sessions are confidential, so participants should feel comfortable that their thoughts won't be shared outside the room. Uncomfortable as it may be, transparency about someone's performance, especially for people in senior management positions, is a good thing. Everyone has things they can improve upon, and the open discussion around what those things are produces much better results for the people being reviewed.

It can be a bit unnerving to know that a room full of 15 people is discussing you, especially when you can hear them all laughing through the wall. But the results are incredibly rich. They add two main things that you don't get by looking at compiled data from an online form: a sense of priority and weighting to feedback, and a detailed look into conflicting feedback. My live 360s in particular have always been far more enlightening than the one-way reviews I received in prior jobs. The commonality in the feedback from different people is a little bit of what one former manager of mine used to say—when three doctors tell you you're sick, go lie down.

Note: One best practice that applies equally well to performance reviews and live 360s is to avoid scheduling them near major events like product releases, marketing pushes, or redesigns. I used to do my own live 360 following a board meeting, but found that the content of the reviews tended to be much more focused around the events discussed in that particular board meeting rather than taking a 12- to 18-month view of my performance. Feedback and postmortems are different processes with different goals. Keep them separate.

One final piece of advice: automate this process! At Return Path, we conducted 360s manually for years (primarily in Excel and Word). Then we moved to an online solution called e360 Reviews from Halogen Software, and now we use Workday. Automated systems have saved us 75 percent of the administrative time in managing the process and it made the process of doing the reviews much easier and more convenient.

Tell It to a Five-Year Old!

I heard this short but potent story recently. I can't for the life of me remember who told it to me, so please forgive me if I'm not attributing this properly to you!

A man walks into a kindergarten classroom and stands in front of the class. “How many of you know how to dance?” he asks the kids. They all raise their hands up high into the air.

“How many of you know how to sing?” he queries. Hands shoot up again with a lot of background chatter.

“And how many of you know how to paint?” One hundred percent of the hands go up for a third time.

The same man now walks into a room full of adults at a conference. “How many of you know how to dance?” he asks. A few hands go up reluctantly, all of them female.

“How many of you know how to sing?” Again, a few stray hands go up from different corners of the crowd. Five percent at best.

“And how many of you know how to paint?” This time, literally not one hand goes up in the air.

So there you go. What makes us get deskilled or dumber as we get older? Nothing at all! It's just our expectations of ourselves that grow. The bar goes up for what it takes to count yourself as knowing how to do something with every passing year. Why is that? When we were five years old, all of us were about the same in terms of our capabilities. Singing, painting, dancing, tying shoes. But as we age, we find ourselves with peers who are world class specialists in different areas, and all of a sudden, our perception of self changes. Sing? Me? Are you kidding? Who do I look like, Sting?

I see this same phenomenon in business all of the time. The better people get at one thing, the worse they think they are at other things. It's the rare person who wants to excel at multiple disciplines and, more important, isn't afraid to try them.

My anecdotal evidence suggests that people who do take this kind of plunge into something new end up just as successful in their new discipline, if not more so, because they have a wider range of skills, knowledge, and perspectives about their job. Alternatively, it could just be that the people who want to do multiple types of jobs are inherently stronger employees. I'm not sure which is the cause and which is the effect.

It's even rarer that managers allow their people the freedom to try to be great at new things. It's all too easy for managers to pigeonhole people into the thing they know how to do, the thing they're doing now, the thing they first did when they started at the company. “Person X doesn't have the skills to do that job,” we hear from time to time.

I don't buy that. Sure, people need to be developed. They need to interview well to transition into a completely new role. Having the belief that the talent you have in one area of the company can be transferable to other areas, as long as it comes with the right desire and attitude, is a key success factor in running a business in today's world. The opposite is an environment where you're unable to change or challenge the organization, where you lose great people who want to do new things or feel like they are being held back and where you feel compelled to hire in from the outside to “shore up weaknesses.” That works sometimes, but it's basically saying you'd rather take an unknown person and try him or her out at a role than a known strong performer from another part of the organization.

Who really wants to send that message?

SOLICITING FEEDBACK ON YOUR OWN PERFORMANCE

As a CEO, one of the most important things you can do is solicit feedback about your own performance. Of course, this will work only if you're ready to receive that feedback! What does that mean? It means you need to be really, really good at doing three things:

- Asking for feedback

- Welcoming feedback

- Acting on feedback

In some respects, asking for it is the easy part, although it may be unnatural. You're the boss, right? Why do you need feedback? The reality is that all of us can always benefit from feedback. That's particularly true if you're a first-time CEO. Even more experienced CEOs change over time and with changing circumstances. Understanding how the board and your team experience your behavior and performance is one of the only ways to improve over time.

It's easier to ask for feedback if you're specific. I routinely solicit feedback in the major areas of my job (which mirror the structure of this book):

- Strategy. Do you think we're on target with what we're doing? Am I doing a good enough job managing to our goals while also being nimble enough to respond to the market?

- Staff management/leadership. How effective am I at building and maintaining a strong, focused, cohesive team? Do I have the right people in the right roles at the senior staff level?

- Resource allocation. Do I do a good enough job balancing among competing priorities internally? Are costs adequately managed?

- Execution. How do the team and I execute versus our plans? What do you think I could be doing to make sure the organization executes better?

- Board management/investor relations. Do you think our board is effective and engaged? Have I played enough of a role in leading the group? Do you as a director feel like you're contributing all you can? Do I strike the right balance between asking and telling? Are communications clear enough and regular enough?

Welcoming feedback is even harder than the asking part. You may or may not agree with a given piece of feedback, but the ability to hear it and take it in without being defensive is the only way to make sure that the feedback keeps coming. Sitting with your arms crossed and being argumentative sends the message that you're right, they're wrong, and you're not interested. If you disagree with something that's being said, ask questions. Get specifics. Understand the impact of your actions rather than explaining your intent.

The same logic applies to internalizing and acting on the feedback. If you fail to act on feedback, people will stop giving it to you. Needless to say, you won't improve as a CEO. Fundamentally, why ask for it if you're not going to use it?

CRAFTING AND MEETING DEVELOPMENT PLANS

Once you have formal feedback, the next step is to turn that feedback into a development or action plan. You may find that people want you to improve 34 different things. Pick the top three and start there.

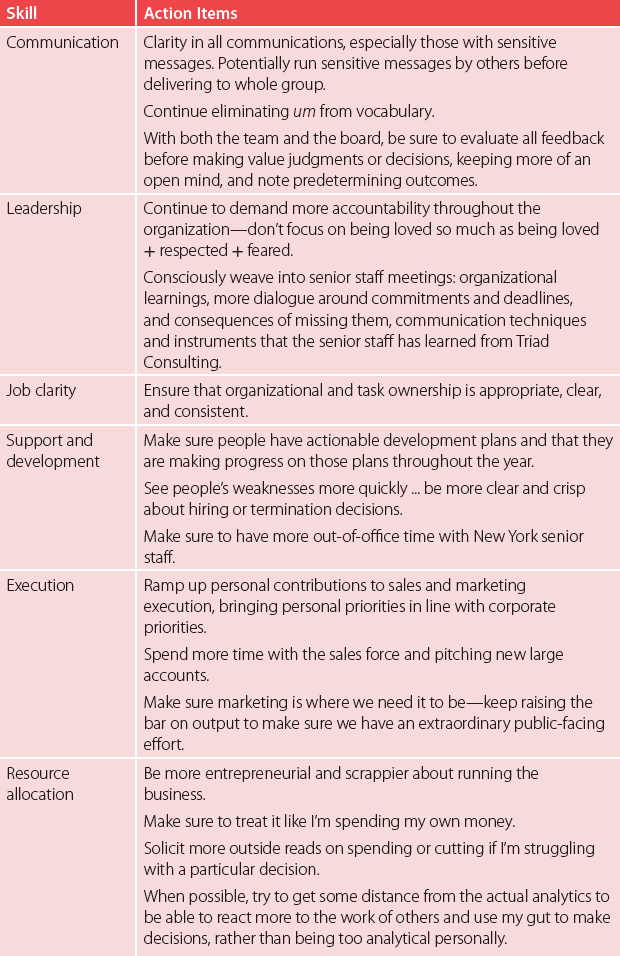

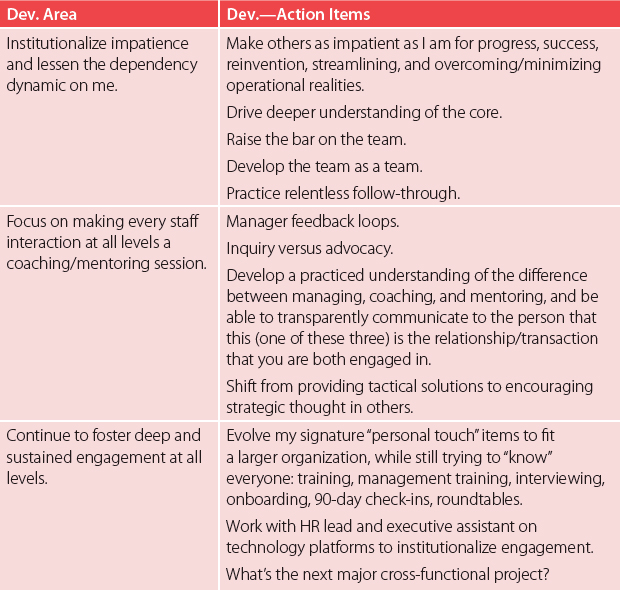

Ideally, your feedback will be clear on this point. If it isn't, go back to your reviewers and ask them to help you prioritize. Then write a simple development plan that includes these top items and some specific actions you can commit to in order to improve. Table 11.1 shows my two most recent development plans.

The process is the same for your team: have them draft their own plans, and review and finalize them together with their facilitator.

Next, you have to make the plan come to life. Start by publicly sharing your plans with each other at an offsite meeting. That kind of sharing really builds trust and lessens the taboo on feedback. (Besides, the feedback originally came from the people around the table.) Then, at least once a quarter, reviews your plans with each other, starting with self-assessments of progress against the plan, then inviting comments from all. As long as your team is honest and authentic, this is a fantastic method for driving accountability against development plans.

For good measure, I publish my plan to the entire company—usually on my blog—and invite anyone who wants to comment on it to do so. The more public the commitment, the more likely I am to stick to it!

TABLE 11.1 Sample Development Plans

The Catcher Hypothesis

Here's an interesting nugget I picked up from a Harvard Business Review article entitled “Making Mobility Matter,” by Richard Guzzo and Haig Nalbantian.

Of the 30 general managers in Major League Baseball, 12 are former catchers. A normal distribution would be 2 or 3. Sounds like a case of a Gladwellian Outlier, doesn't it?

The authors explain that catchers face their teammates, are closest to the competition, have to keep track of a lot of things at once, are psychiatrists to flailing pitchers, and so on—essentially that the kind of person who is a successful catcher has all the qualities of a successful manager.

What's the learning for business? Identify “training ground” positions within your organization. Sometimes, it's pulling people out of their current roles (fully or partially) and putting them in charge of a high-profile, short-term, cross-functional project. Another approach is developing a “mini-GM” role, which should develop a whole future generation of leaders as your company grows.

Who plays catcher in your organization?