CHAPTER TWENTY

THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY OF FINANCING

Making sure you have enough money in the bank is Step 1 in financing your business. Step 2 is finding the money when you need it. This is one of those topics that can take up a whole book (including Venture Deals by Brad Feld and Jason Mendelson) but the high-level overview here should get you pointed in the right direction.

Let's start with the premise that there are three forms of financing for your business: equity, debt, and bootstrapping. The difference is that selling equity is trading cash for ownership in your company; taking on debt means you need to pay the cash back; and bootstrapping means neither—but it might be impossible for you, depending on the business you're building. One of the most important principles to remember here is that debt is always senior to equity (meaning it always gets paid out first).

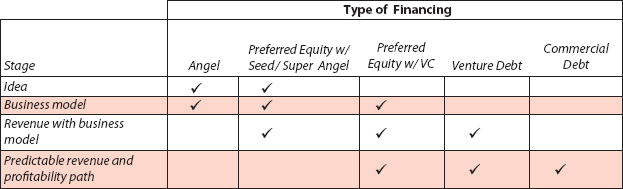

What kind of financing should you be looking for at the current stage of your startup? Review this matrix from Return Path Cofounder and CFO Jack Sinclair to find out (Figure 20.1).

FIGURE 20.1 What kind of financing should you be looking for at the current stage of your startup?

EQUITY INVESTORS

When CEOs think of equity investors, the first words that usually come to mind are venture capitalists (VCs). VCs aren't the only investors in the startup world. Inexperienced CEOs often learn this lesson too late, overexposing their idea to VCs who aren't ready to invest in something so early stage—and aren't likely to reconsider the idea further down the road.

I discuss VC economics in depth in this chapter and provide tips for negotiating with them in the following section. Here, I'd also like to introduce two other varieties of investors: angel investors and strategic investors. Again, if you want a lot more color on the nuances and different terms and security types associated with equity financing, read Venture Deals.

Venture Capitalists

VCs are professional investors who invest money on behalf of institutional investors.

The Good: VCs are the cream of the crop for startup investors. They're well-funded; they're experts in helping companies grow; and they're prepared for the risks and roadblocks that every startup venture entails.

The Bad: As a startup CEO, you will raise money a handful of times. VCs do this for a living. The combination of an inexperienced CEO and a savvy-but-cynical VC could be fatal—for the CEO. There are plenty of horror stories about VCs writing deals that are extremely disadvantageous for CEOs—mostly because these CEOs fail to get past the excitement of a multimillion-dollar investment and think through the consequences of various clauses—“Liquidation Preference,” “Conditions Precedent to Financing”—that any experienced VC will include. (There's an easy fix: read Venture Deals!)

The Ugly: VCs essentially have a right of first refusal on the future existence of your company: if they don't invest in subsequent rounds, it will be extremely difficult to find other investors. (Why would anyone take a risk that the investors who know you best have chosen to pass on?) With Series A and subsequent rounds, this is a risk you may have to take. This is a good reason to avoid VCs in angel rounds. Throwing $200,000 into an idea is extremely low-risk for a VC but they will only provide follow up investment for a handful of those deals. If yours isn't one they follow up on, you could be sunk.

Angel Investors

Though there are institutional “angel” groups, angel investors are typically high-net-worth individuals who put personal money into a company.

The Good: Angels are often your friends and family, so they don't play hardball when negotiating terms.

The Bad: Angels are typically your friends and family, so every dinner party you attend has the potential to morph into an ad hoc investor relations conference. You can blunt this by designating some social times as “work-free zones,” but it's still there, lurking in the background.

The Ugly: Angels are typically your friends and family, so you will feel awful if you lose their money or radically dilute their investment in subsequent rounds. When you take money from friends and family, be sure to look them in the eye and tell them that they should be prepared to lose all of it but that you will do your best to avoid that outcome.

At the end of the day, not everyone is cut out to invest in startups. My biggest takeaways about nonfinancial/VC investors are:

- Be very selective about who you let invest in the early stages of your company.

- Make sure angel investors acknowledge to you verbally (above and beyond the accredited investor rep they give you) that they are totally comfortable losing all of their money.

- Make sure angels and strategic investors understand that in order to preserve the value of their investment, they may need to continue investing in your company if you end up raising multiple rounds of financing.

- Without being unfair, try to limit the rights (or assign them by proxy to you or to the board or to a lead investor) of less sophisticated financial investors who aren't and won't be close enough to your business to participate in major corporate decisions down the road. Along these lines, you should strongly consider selling common stock to both types of investors, especially if it's early in the company's life.

Above all, don't be tempted by dumb money. You want your investors to be partners, not blank checks. While you might get much better terms with angels—or even strategic investors who haven't made many investments—you will earn much more valuable partnerships when you bring a good VC onto your team.

Strategic Investors

Strategic investors are operating companies (not investment firms) that invest in other operating companies.

The Good: Strategic investors are typically some kind of business partner. If they have a stake in your company, they're more likely to help you.

The Bad: The person at the company who made the investment decision is usually a different person than the person with whom you conduct business, so the incentives are rarely aligned the right way.

The Ugly: Unlike institutional investors, strategic investors can change their philosophy about making other corporate investments for any reason or for no reason. While they might participate in subsequent rounds, they're far more likely than VCs to leave you without support in future rounds and with an unproductive player around the table. That makes securing subsequent funding—or a future exit—much more difficult. The best way to mitigate this is to insert some kind of “pay to play” provision in the financing but prepare for a fight on this front.

Dumb Money

There's nothing worse than dumb money backing a dumb idea or management team.

The dumb idea or team can destroy an emerging sector pretty quickly and the dumb VC behind the deal will just keep ponying up and muddying the waters for everyone else.

The classic dot-com version of dumb money is the company that decides to give away its core service for free in order to try making money at something undefined or untested. It could take two years and a ton of VC money before that company is out of business, having figured out that they needed to charge for their core business—and that process can wash out smarter and more conservative companies in the process.

So instead of just cheering that your competitor is dumb, dig in and look at how smart the money is behind the company. If the money is dumb, too, beware!

Smart Money

The converse of “dumb money” is that there's nothing better than smart money behind a great idea and solid team. Here, in no particular order, is my list of the 10 characteristics of great investors:

- Great investors know how to give strategic advice without being in the operating weeds of a company.

- Great investors get to know whole management teams, not just CEOs. In fact, great investors become part of the extended management team of their portfolio companies.

- Great investors invite you to do due diligence on them by giving you a list of every CEO they've ever worked with and asking you to pick the ones you want to talk to.

- Great investors ask great questions.

- Great investors don't publicly take credit for the success of their investments, even if they were major drivers of that success.

- Great investors show up for meetings on time and don't spend the meeting using their smartphone.

- Great investors treat their portfolio companies' money as if it were their own money when spending it on things like lawyers or travel.

- Great investors look for connections to make between their portfolio companies or relevant people but have a strong relevance filter and don't send junk.

- Great investors never have a ready-made list of the ways they add value to companies—and they specifically never talk about the help they give in recruiting executives or making sales/biz dev introductions.

- Great investors recognize when they have a conflict around a portfolio company and are clear to represent their points of view with proper context, recusing themselves from meetings or votes when appropriate.

You owe it to yourself to have great investors backing you. Find ones who meet every criterion on this list.

DEBT

If you don't have access to high-net-worth individuals—and you don't have significant savings yourself—starting a company can be extremely difficult. There are a number of types of debt you can take on to finance your business. While debt typically makes more sense for mature business, there are times when debt can work for a startup.

Convertible Debt

Sometimes angel investors, or even early stage venture capitalists, will want to structure a deal as convertible debt instead of equity. That means you're taking on debt, which will have to be paid back per the terms of the loan, unless it converts into equity based on whatever triggers you agree to. The triggers could be around company milestones, like revenue or product shipping, but they could also be around financing milestones, like attracting other investors to the table, where the debt would convert to equity at the terms of that financing, or maybe at a slight discount to those terms.

The Good: Convertible debt isn't a bad deal at all for a young company. It makes particular sense if you are already working on a venture or strategic financing and want to pull in a little cash earlier but are nervous about setting the terms of that financing in a way that might spook the larger investor.

The Bad: A hastily written convertible debt agreement could convert too much of your debt into stock for your investors. This is an early stage strategy—too early to give away a significant chunk of your company.

The Ugly: This form of debt is a bigger drag on your balance sheet than most other forms of investment. In good times—economic and for the company—this isn't a major consideration. In hard times, it can limit your options.

Venture Debt

Venture debt is essentially a combination of debt and equity. It is cheaper in terms of dilution than preferred equity but it has to be paid back with interest in between one and three years. Because of the payment requirement, you will need some revenue and a proven business model in order to raise venture debt.

The Good: Early payments will often be mostly interest, with most of the principal paid near or at the end of the term. If you have a good venture partner they will often enable you to renew the principal at the end of the term for additional consideration.

The Bad: Venture debt investors don't require board seats, but they do have operational demands like standard reporting, senior liens on all assets including intellectual property (senior to any other equity but junior to commercial debt) and sometimes basic financial covenants. The equity piece is normally structured as “warrants” that enable the investor the right to buy a certain amount of shares at a fixed price, usually the price of your last round of venture financing.

The Ugly: “Interest-only” are interest-only for a specified term. If the underlying asset—your company—proves to be worth more than the size of the loan, this won't be a problem. Otherwise, you will be stuck with a significant principal payment down the road. If you think that's an unlikely scenario, just ask a homeowner who got stuck with a balloon payment in 2008.

Bank Loans

Banks are how most traditional companies get their financing. Traditionally, they're not the right place for startups. Startup investors take the uncertainty of startup business plans for granted. Those uncertainties will be nonstarters at your local branch.

The Good: Bank loans are relatively transparent and you're not likely to be surprised by a complex set of terms. They'll give you X, you have to pay back X plus interest on a regular schedule.

The Bad: Banks won't bankroll ideas that are years away from producing revenue. Business loans are great if you're opening a storefront or another traditional business but they won't patiently wait for your startup to hockey stick. Why should they? No matter how successful you are, their upside is fixed in advance.

The Ugly: You can't miss payments, no matter how big next quarter is going to be. Everything your company owns is potentially collateral and it won't take long for the bank to start calling it in—and many banks ask for personal guarantees. It's not exactly the Goodfellas “F*&% you. Pay me.” But it's not that far off unless you're well into the growth stage, or at least the revenue stage of your startup.

Personal Debt

Maxing out your credit cards. Mortgaging your house. Mortgaging your parents' house. You hear about these things from time to time. They are part of the romance of startups. Once in a while, they work. There's also an extremely personal element to this decision that has a lot to do with one's family circumstances (both your own and that of your parents).

For me, I'd never really want to do this beyond a bare minimum of a few months' worth of Web hosting expense and some basic marketing materials (and forgoing salary). If your idea is that great, you should be able to find someone to help you finance it. If nothing else, see the next section on bootstrapping. 95 percent of startups fail and putting your personal credit score on the line to fund your dream is a higher-stakes game of poker than even the thickest-skinned entrepreneur should engage in.

BOOTSTRAPPING

Not every startup is founded with an infusion of capital, nor do they need to be. The other option is “bootstrapping”: funding a company from your personal finances and your initial operating revenues. The two most common types of bootstrapping are customer financing and your company's cash flow.

Customer Financing

Customers don't lend you money; they pay for your services. Some are even willing to do so in advance. That's called customer financing. If you can pull it off, it's great.

The Good: If customers will pay for your products and services in advance (think Kickstarter or Indiegogo for business-to-consumer [B2C] and you can also sell something to a big enterprise customer ahead of delivery), it's incredible validation of the market value of your idea.

The Bad: Customers can react very badly when startups fail to meet milestones. VCs expect this but customers may never come back.

The Ugly: As diverse a group as “customers” may sound, the consumer end of this entire category may be eliminated by the failure of a few prominent, crowdsourced projects. It's too early to tell but this is a real danger that entrepreneurs in a hurry should be wary of. Business-to-business (B2B) customer financing, however, is much more like finding a strategic investor.

Your Own Cash Flow

Your own regular cash flow (not maxing out your credit cards) is another way to finance a new venture—for a while. This usually takes the form of starting a business off the side of your desk while you still have another job, or starting your company and then doing a bunch of consulting work on the side to pay some of the bills. (Consult an employment lawyer before doing this to understand the intellectual property risks you're incurring.)

The Good: You retain all the equity and don't take on any debt or customer expectations.

The Bad: You find yourself serving two separate masters at the same time, which is a difficult juggling act, at best.

The Ugly: You completely burn yourself out because you're effectively doing two jobs—then what happens to your new company?

After making a modest investment of your own time and resources, you really can't launch a startup without finding another source of funding. Let this sense of urgency drive your search for financing but don't let it lead you to the wrong kind of financing or the wrong investors. Whenever an opportunity presents itself, review the Good, the Bad and the Ugly in this chapter and make sure it's an opportunity that will lead to success and growth—rather than a short-term infusion of cash that will lead to long-term headaches.