Chapter 7

Lensing

Imagination is not only the uniquely human capacity to envision that which is not, and therefore the fount of all invention and innovation. In its arguably most transformative and revelatory capacity, it is the power that enables us to empathize with humans whose experiences we have never shared.

—J.K. Rowling

ON THE TV screen, a red convertible whips by a man walking along the side of the road. The car stops and reverses back to the man, presumably to ask him if he needs a ride. The beautiful woman driving the convertible rolls down the window, lowers her sunglasses so you can see her eyes, and asks the man seductively, “Are those Levi’s jeans you are wearing?”

What red-blooded American male wouldn’t run out and buy a pair of Levi’s jeans after seeing that commercial? Equally, what woman wouldn’t envision herself as the main character in that ad—in control, asking the questions, treating the man as the sex object?

One of the major tenets of advertising has traditionally been an attempt to make consumers see themselves using the product and replacing the image of the person on the screen with themselves. The goal was to drive demand for the product through the influence of suggestion or role-play, with the marketer telling consumers exactly what they need to be sexy, powerful, or successful.

This concept of visualization is one of the main reasons realtors encourage you to stage your home when you’re trying to sell it. Once the buyer envisions himself or herself in the space, living there, sitting on the couch watching TV, or sitting at the dining room table eating breakfast, you are that much closer to a sale.

Think about how you approach making any major life decision in your own life: buying a car, purchasing a home, deciding whom you are going to marry. In all these cases, you spend time “trying it (or him or her) out.” You test-drive the car, tour the home, and go out on dates. You want to make sure you can see yourself being content with your choice in the future and that it will fulfill your needs and your vision of how you want your life to be.

This applies to even small purchases such as clothing. The long-standing tradition has been to go through the exercise of taking an article of clothing into the dressing room and trying it on for size—or to ensure that the store or website has a very liberal return policy.

The new world of marketing and product development is clearly very different. Instead of creating a vision that makes the consumer want to own your product, use your service, or participate in your experience, it’s now the brands’ turn to “try on” the consumer’s core drivers and motivation and to see their product, service, or brand from the consumer’s perspective, or rather how it benefits consumers and fulfills their unique needs.

This might sound like a daunting task. However, doing the work to ladder your consumers and unlock their DNA means that you will know them in a deep and authentic way—and more important, as more than just a demographic or segmentation. You will have the same information about your consumers as you know about your closest relatives or friends, people for whom you can always pick out the right gift or predict their reaction to a piece of news. It will be less like the relationship you have with, say, your second cousin who invited you to her wedding, clearly a case where it’s more difficult to buy an appropriate and meaningful gift.

The new consumer seeks brands, products, and experiences that already feel like them. They have no interest in brands that attempt to convince them through manipulation or idealism that their product is the right one for them.

You can and should use the knowledge you’ve uncovered during laddering to start building your products and marketing messages from the consumer’s perspective. In fact, this is the most important and most rewarding result from taking on such a project. It’s the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Unfortunately, I’ve found that this is also the step that most companies overlook and underutilize. They view the process of understanding their consumer groups merely as something to check off in their project plan. I can’t say that I completely blame them, because most are still depending on unreliable and old-school research techniques such as focus groups or surveys. As a result, they 1) don’t build methods for purposefully and systematically including the knowledge gained in their overall process and 2) the methods they are using provide unreliable results that can easily be misinterpreted or misunderstood.

To conduct laddering work on your consumers and never use it is like building a beautiful house and choosing to never live in it. What’s the point of doing all that work if you aren’t going to enjoy or benefit from it somehow?

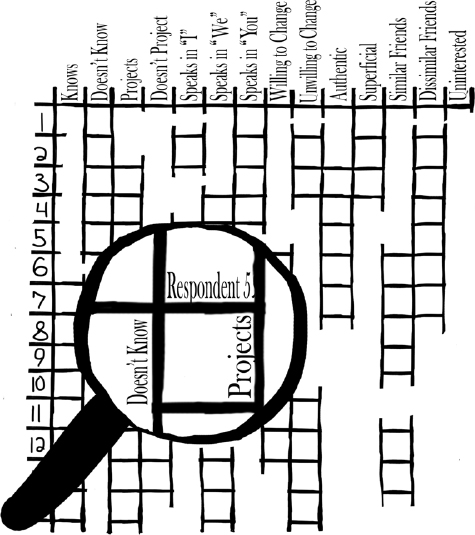

You should benefit from it, of course, and this chapter will show you how. The exercises within will help you view and understand the world through your consumers’ eyes by using a process I call lensing (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Use Lensing to Apply Consumer DNA to Your Initiatives

Understanding Your Brand

For lensing exercises to work effectively, you must truly understand who your brand is to your consumers and where you stand in relation to them. This might require some tough love.

Companies build words, messages, visuals, and mood boards to relate their overall objective for how they want the public to view both the company and the individual brands underneath its larger umbrella. This information guides the type of advertising they produce, the products they build, and even the feel of their stores or product displays.

Some companies that do this well include Apple, Target, Gap, and the Coca-Cola Company, to name a few. You already know that a message or advertisement is coming from one of these companies before you ever see their logo. These brands have a close alignment between the way that they see themselves and how their consumers see their brands. Take Target, for example. It has done a great job of taking discount to a whole new level and uses its branding to differentiate its company from other like retailers, for example, Walmart, K-Mart, Dollar General, and Dollar Tree. Target even takes time to repackage some products to make sure they feel like Target. The company has invested a great deal in consumer experience testing to ensure the overall experience stays consistent with what consumers expect from them.

However, Target is the exception, not the rule. Most companies have worked to develop their brand expression only internally. As such, it reflects a highly aspirational view but doesn’t often reflect reality. Although aspirations can lead to great things—indeed, both Target and Apple initially had to take an ambitious approach to become the companies they are today—you must start not from where you want to eventually be but from where your consumers think you are today. Only then can you define the steps it will take to match your consumers’ view with your view.

To determine what this is, ask yourself and your team: What words would our consumer really use to describe our brand? How would our brand appear as a person?

For example, you might need to distinguish what your brand aspires to be (for example, hip and cool) from what it is today (stodgy and staid). That doesn’t mean you can’t get to where you want to be, but you have to start with who and what you currently are.

It’s a lot like the process of trying to lose weight or get into better shape, and it’s something you know won’t happen overnight. You have to assess where you are today by determining what you are doing right and what you are doing wrong and then develop a plan that will get you to your ideal state sometime in the future with a plan and milestones to get there. No miracle drug, patch, or contraption is going to circumvent the hard work required—just as no specific marketing campaign will change the public’s perception of your brand overnight. You need to think about the current state of your relationship with the consumer in the same way. Understand and accept your consumers’ perception; then determine what it takes to move closer to them, not to try to make them move closer to you.

When you walk into a cocktail party or any other social event, you are naturally drawn to others you already know or have an affinity toward. Consumers interact with brands and products like they do with other people at a cocktail party. They tend to spend the most time with their closest friends—the ones they already have an affinity toward. We form snap judgments about those we are meeting for the first time, and we do the same with new brands. Consumers carry with them a set of well-ingrained opinions about the brands that have been around for a while, and it takes work to change their perception.

The way your customers perceive your brand and product attributes is a far more important aspect in their decision making than your offering’s features, functions, or even quality. These aspects are a given and easy to compare for the consumer. They will weed out an inferior product well before it makes it into their ecosystem. I recently heard a marketer at a conference make a seemingly obvious yet still significant statement: “Being good or reliable is a given. No one buys your car or product because it starts. That is expected.” Therefore, you must deliver something far more compelling and meaningful to consumers to make it worth their time and attention.

Breaking Down Internal Barriers

Consumers see your company and your brand as one cohesive entity, so what one part of the organization does has an impact on their overall perception. This is why you must direct the development of a relationship with the user, and the process of really understanding who that person is, from the top of the organization down.

If you only fix a specific problem with a message, a product, or a customer service issue but fail to affect change across the organization, you haven’t really corrected the problem at all. It doesn’t matter how great a product or service is if the teams selling and supporting it don’t view the consumer holistically and from the consumer’s perspective.

My experience tells me that companies work too much in silos. And although each silo is responsible for fixing their part of the equation, they rarely pass information they learn over to other groups. For instance, marketing may learn that consumers don’t understand a certain word or phrase being used in the company documentation, but they never pass this information along to their customer service group or sales representatives. Even if they do share, it tends to be watered down from what they’d originally learned.

I often see companies viewing themselves as specific internal silos as well. Consumers don’t understand the makeup of your organization, and honestly, they don’t care. They want your company, from the time they first interact with you until they complete a transaction, to understand them holistically.

Companies don’t do this out of spite, of course. Teams frequently have to do more with less, so they do their very best to meet the objectives they’ve been given within the areas they can control. To create a real impact, you have to put a system in place, the same way you would with manufacturing or technology departments that fosters and shares new information from user interactions across the company’s ecosystem. The system needs to be driven from the top down and consumer information needs to be available centrally to all of the systems that run the company. Disney and Zappos are two well-known examples of companies that are consumer-focused from their executive team down. This focus and attitude is built into their company’s culture.

Influence and Affirmation Has Changed the Buyer’s Journey

In the new economy, consumers choose entirely on their own to include a product or service in their inner circle; they will then will look to influencers to help affirm this choice. This is a common modern-day use of social networks both online and in person.

For example:

- Pre–Mass Customization: Vicky sees her friend Cathy using a product or wearing a new brand and asks Cathy where she got the product. If you watch a movie from the 1980s, you can see this obsession with and focus on status brands such as Chanel, Gucci, or Member’s Only jackets throughout. Vicky then goes to the store to buy the same thing. She has been influenced by Cathy’s purchasing decision, and Vicky is making her choices based on a desire to fit in with Cathy.

- Post–Mass Customization: Vicky hears about something new regarding a brand or product. This messaging might appear on her favorite blog, in her Twitter feed, on a Pinterest board she follows, or in an article by someone that she knows and trusts has written. She decides that it feels like her and she then looks to Cathy for a final affirmation before making the purchase. Vicky is making her own choices here; she’s merely checking with others to affirm her choice and vouch for the brand or product.

This alignment in the post–mass customization era is displacing the traditional sales representative and has forever changed the buyer’s journey. One of the most interesting parts is how it is turning everything we’re used to on its head. More complex products that used to require a higher-touch sales approach now need transactional sales, whereas transactional sales items need relationships.

For example, think about how we buy cars now versus the way we used to only few short years ago. Buying a car used to be quite an ordeal. The consumer would visit multiple dealerships, spend time driving different cars, try to muddle through the available information in brochures and car manufacturer–created content, and listen to the salesperson’s pitch to determine which car would really fit his or her needs.

All the research, knowledge, and insight we need to buy a car now is at our fingertips thanks to blogs, websites, and content available on social media sites. The sales rep has become a mere order taker.

For example, I own an RV and needed to buy a replacement vehicle to pull it. I was in negotiations for a Mercedes Benz GL450. All the specs for the vehicle indicated it could pull the RV without a problem and do an even better job than the vehicle it was replacing. The sales rep with whom I was working assured me that it could accomplish this task without a problem, but I wanted to verify this for myself. One of the biggest barriers I had to overcome was that I couldn’t find a single picture of a GL450 pulling an RV anywhere on the Internet. I finally decided to buy the GL450 and immediately posted a picture of it pulling my RV (which it does incredibly well) so that others would feel comfortable making the same decision.

Selling Power magazine publisher Gerhard Gschwandtner recently predicted that the number of salespeople in the United States could decline from the current 18 million to around 4 million by 2020. He quoted a Gartner report that projected that 85 percent of the interactions between businesses will be automated by that time, without any need for human interaction. This statistic certainly has the potential to be true. Think about it: the purchaser has everything needed to make a decision before stepping into a store or talking to a salesperson. The salesperson becomes a final checkmark, not the reason the consumer makes the decision. In other words, the big risk for a salesperson is the potential to deter a sale, not encourage it.

Understanding what consumers want to hear and don’t want to hear from your brand or company is crucial to maintaining or changing who they perceive your company to be.

Stop Trying to Change Consumer Behavior

Much to my dismay, I often hear and see companies attempt to prevent their consumers from shopping multiple sites before making a decision. This is a waste of effort. We have at our deepest core a desire to hunt, compare, and rationalize. No matter the promises or the guarantees included throughout a site, it is human nature to look at multiple sources before deciding whether something is true or correct. Only the truly loyal are already going to buy from your site with very little comparison. It’s just as hard to make a loyal consumer shop somewhere new as it is to prevent a non-loyal consumer from performing comparisons.

Let’s say that your consumer is collecting points or has some level of prestige with your organization. That particular individual won’t spend very much time comparing you with other brands and sites. Because I am an Atlanta resident, where Delta Airlines is headquartered and is an important part of our city’s heritage as well as the most prevalent airline, I am loyal to Delta. As long as its nonstop price from Atlanta to the location I am headed is within $50 of the other carriers, I am going to book with Delta. I will do a comparison using one aggregator and will immediately gravitate toward a Delta choice. Money is something that consumers always cite as a factor in their decisions. However, as I discussed earlier in this book, it’s more important to understand the consumer’s view and relationship to money than to focus on the actual cost. You must remove cost as a deciding factor during laddering and lensing exercises and apply it as a filter only after you’re done understanding the core drivers.

Consumers quickly sort and organize companies, brands, products, and services into mental buckets—and then keep them there. It is extremely difficult to alter someone’s perception of what you are good at or known for. Although some big names such as Apple have achieved this by becoming a music, book, and video store, this is not a feat many companies can accomplish—and Apple didn’t do it overnight. It’s far better for you to become the very best at whatever the consumer views you as than to risk trying to become something your consumer believes you are not.

When you recognize the ways your consumer chooses to interact with your brand or company, embrace it; don’t fight it. Instead, learn how to capitalize on these preferences. Many brands make the mistake of ignoring a channel (e.g., Twitter or Facebook), and once you ignore it for too long, it is difficult—in fact, usually impossible—to recapture.

Staying Top of Mind versus Acquisition and Support

Some brands are using digital experiences and sponsorship to keep their product top of mind for users. If this is your marketing’s primary aim, lensing exercises help you evaluate where to place this content, as well as what it should (and shouldn’t) contain to appeal to the right clusters. For instance, if your product is funny or quirky, the top-of-mind experiences need to be aligned with that. Trader Joe’s and Old Spice are both examples of brands that do a great job of embracing and promoting their brand message. Grocery store chain Trader Joe’s has always known who they are, from the quirky newsletter they send out to their handwritten price signs throughout the store. Similarly, male grooming products maker Old Spice is a good example of one that went from “your father’s brand” to one that has been embraced by a younger set. This occurred largely thanks to a unique and well-orchestrated marketing campaign featuring the Old Spice Guy and, more recently, Italian fashion model Fabio. Old Spice accomplished this top-of-mind currency by accepting who they were and moving themselves across the consumer chasm to enter the ecosystem of a new group of consumers.

If your brand is caring or high touch, reaching out on birthdays and other important events makes sense. A brand that is utilitarian, like your power company or cell phone provider, not so much.

The new rules of acquisition and staying top of mind will mean different things to different clusters. Some want information concisely and quickly, whereas others trust third parties over receiving information directly from the company even if the information is exactly the same.

Content Source and Distribution Are Paramount

I have determined during lensing exercises that companies often need to create and distribute the same content through two different channels: one channel branded as from the company and the other, from a third party. Although the content is exactly the same, the source is so highly crucial to the various clusters’ sense of trust and relationship that it must be delivered different ways.

The same is true with support—that is, different clusters need different levels of support, but not in the way that is traditionally established. You’ll recall from the BellSouth case study cited after Chapter 2 that there were clusters of individuals who wanted to be taught how to solve the problem as part of the support process. Other clusters cared only about having the problem fixed as quickly as possible; they had no desire or requirement to understand why a problem occurred. When companies establish support teams, they often default to first-, second-, and third-level support based on the severity of the problem. They fail to consider the much more crucial elements: the consumer’s perceptions and core DNA.

Lensing will help you figure out exactly who needs and wants what by mapping certain types of users to certain support channels and content. By using lensing, you can craft the right messages to reach out to your user communities and determine the priority you are placing on different support channels. A decision to ignore a channel may be a decision—albeit an uninformed one—to cut off one of your clusters. And once you become known for ignoring or abusing a channel, it’s almost impossible to repair the damage that’s been done.

One company I work with is constantly responding to their user clusters using the word free. But because this is a higher-priced brand, consumers who buy from it don’t care whether something is free. The word easy would be more effective in this case. In addition, they often respond to consumers by lurking on different social media channels and replying to those complaining about their service, without being invited to do so. This will alienate certain consumer clusters from that channel and cause them to see the brand as out of touch, pushy, and clueless about establishing relationship. If this brand analyzed the follow-up messages between the consumers they are following through lurking, they would see how uncomfortable this makes certain people. By reading their profiles and the other information they share in their feeds, they could easily identify each consumer’s cluster and understand the why behind that person’s decisions.

Identify the Primary and Secondary Clusters

It is critical to identify the primary cluster for any given product or campaign—and no, it cannot be everyone. Which cluster is either closest to the product or most likely to resonate with the campaign? This becomes your primary group for your lensing exercise. It’s fine to choose a secondary cluster, as it can be necessary and appropriate for reach. Make sure, however, to keep this secondary group in the proper place when performing your evaluation.

Two ways of using the results of laddering and latticing is through standard lensing exercises such as brainstorming and evaluation.

Brainstorming

Lensing exercises support powerful brainstorming sessions with your team. You can use the information you have learned about your consumers to prioritize information from the user’s perspective. Start by blue-skying the concept you are considering working on, just as I outlined in Chapter 5. But this time, perform the blue-sky activity from the perspective of the cluster.

If you are selecting primary and secondary clusters, you can assign half of your team to play the role of the primary cluster and the other half to play the secondary cluster. This creates a natural and important conflict in the process that requires the team to think about the new idea from the consumers’ perspective, not their own. Proceed in the same manner as you did for confirming clusters, but use the consumer DNA you’ve gained to vet the ideas and determine why an idea might or might not work. You should conduct end-of-process voting from the perspective of the cluster, not the participants’ point of view.

It’s best to hold this type of brainstorming session using cross-functional teams, composed of members who touch the consumer at different points throughout their life cycle, from awareness to support. Part of what the marketing department and product development teams of the future must do is break down the barriers between the different internal groups. Consumers buying from you don’t see these kinds of internal divisions, nor do they care about them. You are one brand and one company in their mind, so that’s what you must strive to be in reality as well.

It was in one such brainstorming exercise that a participant suggested gun ranges as a stress relief option (see Chapter 5). I stated before that this seemed like an outrageous suggestion, but we put it on the board anyway. And good thing we did because when we evaluated it from the primary cluster’s needs and core drivers, it created a flow that produced a whole set of potential services, including spa and beauty services and golf outings. Although that specific recommendation didn’t make it into the final cut, without it, we might have missed an entire section of ideas that led to a successful solution that met the cluster’s core need which was access.

Once you are done with the brainstorming session, sort the ideas into buckets of like items. Then use a voting system from the perspective of the cluster to reduce the number of items down to about 10 percent of the original suggestions. You can use this narrowed list to test concepts with your clusters and understand what’s truly important to them.

I know that I discouraged focus groups earlier. However, this is a good time to reintroduce them into the mix. Just remember to recruit your participants based on the clusters—not their segmentation or demographic characteristics—and let the participants lead as much of the ideation session as you can, rather than trying to guide them yourself. Remember, the consumer is the expert. You should use these precious opportunities to extract as much as you can from them to learn how to truly establish and maintain a relationship, and drive your product and service ideation.

Evaluation

Once you understand what your consumers really want, you can begin to evaluate every campaign through their eyes. You will empathize with how they will experience the campaign, what words you need to use, how they will react, and what stumbling blocks they may face. For instance, I do not know how to be a 40-year-old female with two kids and a mini-van. However, thanks to the work I have done laddering consumers, I do know how to be someone who likes authentic experiences; is interested in projecting herself but guarded by what she says; prefers to speak in first person; likes to spend money but think she is saving; and shares online, because she is more connected and comfortable there than in person.

I use many techniques for lensing based on the maturity of the idea or concept. I’ve found that more concrete the concept or idea is, the more concrete the evaluation can and should be. Some techniques that work well for performing lensing evaluations include:

- SWOT: A simple strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats analysis goes a long way to identify what parts of a concept or idea are solid and determine what you might need to do to either make the concept work or decide it’s a bad idea altogether. Simply review your primary consumer cluster’s key tenets or drivers, and start to list the attributes in these four different categories. If you find it difficult to sort the aspects or elements of what you are evaluating in this way, simply draw a line down the middle of the page and create a pros and cons list.

- News Reporter: This is especially helpful when thinking through a brand-new concept and determining what’s necessary to meet the targeted consumer cluster’s needs. Answer all the same questions about the idea that a reporter would have to. Determine the who, what, when, where, why, and how of the idea. Then look for gaps or incongruities in the story, specifically in terms of what drives the consumer cluster to an awareness, participation, or acceptance of something new.

- Artifact Idol: This works well to narrow an idea’s concepts when you’re considering its impact on multiple clusters. Ask different members of your team to judge the concept from the cluster’s unique perspective. That way you can understand how to introduce the idea and what it might take to get it to move across the different groups successfully.

Depending on the situation, there are many other activities you can perform that are similar to the ones described here. Look to standard focus group or brainstorming activities as a starting point, and think through how it might be modified for a lensing approach.

Again, it’s best to perform all these activities using cross-functional teams. Each person and group brings unique subject matter expertise and thoughts to the activity. When describing the attributes of the consumer clusters, I often see members of the sales team say things like, “Oh yeah, I’ve met that guy before,” or support staff employees state, “That sounds like the last person I helped on the phone.” As a result, these exercises make the consumers real to your employees, something that goes a long way in getting them to start thinking about their work differently.

The Result—Actionable Project Briefs, Product Roadmaps, and RFPs

Writing a project brief or plan to move forward after a lensing exercise makes the components truly actionable for members of a design, creative, development, or implementation team. Instead of receiving a generalized set of instructions for what to build, they have a specific direction in which to go with information on the elements they need to include in the process—and why. The brief serves as a highly valuable roadmap to which the team can refer back during the development process and continue to reference to make sure they are on track.

The results of lensing create a solid set of requirements that can be used to inform any new technology selection, process implementation, or improvement. You can craft incredibly powerful requests for proposal (RFPs) with this information at your team’s fingertips. The ultimate vendor selection should be based on a solution that will best fit the intended consumers’ needs.

Lensing is one of the most powerful and important outcomes of laddering your consumers. Indeed, it’s the goal: to be able to deeply understand your consumers and evaluate everything you plan to do from their point of view is what will separate your organization from the rest. It allows your team to work hand in hand with consumers and build exactly what they want and need. It’s a fundamental change in the way your organization approaches its work—an outward-in look at all the initiatives, campaigns, and product launches you undertake. Most important, to survive and thrive in today’s mass customization world, it’s the step all companies must take or risk being left to languish in old, dying paradigms.

In the next chapter, I will discuss how to socialize your laddering and lensing work throughout the organization to support a fundamental change in thinking.

- Lensing is one of the most powerful aspects of laddering, because it puts your team in your consumers’ shoes.

- You must be honest about where you stand with your consumers to properly bridge the gap from where you are to where you want to be.

- For the lensing process to work properly, you may need to break down some internal barriers that prevent knowledge from being shared across the entire organization.

- The buyer’s journey has been fundamentally and permanently altered. As a result, consumers make their own decisions and look for affirmation after a purchase or decision.

- The rise of choice, avenues for product use and selection, make it impossible to change consumer behavior. Companies must instead learn how to exist within their consumers’ behavior patterns and build products and services that meet consumers’ individual needs.

- The approach for acquisition, staying top of mind, and providing support is very different than it used to be. You must deploy different lensing approaches and establish different measurements of success.

- You must lens with a primary cluster in the forefront while being mindful of how the secondary cluster is affected and what their level of participation is.

- Lensing will result in actionable and measurable initiatives for your team to help the company move forward.