Chapter 4

The Steps to Laddering

Why do you wear a mask? Were you burned by acid or something?

Oh no, it’s just they’re terribly comfortable. I think everyone will be wearing them in the future.

—The Princess Bride

WHETHER WE REALIZE it or not, we put on a mask every morning as we head out into the world. Some of us wear the mask of successful business owner, while some present ourselves as teachers, skaters, doting mothers, or renegades.

We create an external identity of who we are, and we are careful to present ourselves that way as we go about our daily tasks. We use our clothing, appearance, and speech to communicate this identity to others.

Yet who we present ourselves to be in public is very different from what others might observe about us if watching us in our most intimate of places, such as our homes, cars, and offices, or even if looking through our bags and purses. It takes getting into these intimate places—beyond the mask we present—to understand who we really are underneath. And as we move even further into the era of the acceptance of the individual, we choose to buy from and associate with brands that resonate with who we are at our core. We avoid those that try to sell to us or change our fundamental behavior.

In his book Blink (2007), author Malcolm Gladwell introduces and discusses the concept of thin slicing. In my experience, this is a much faster way to get an idea of a person’s core than simply listening to what that person tells you, especially if that person has been paid to come to an unfamiliar environment or participate in an artificial scenario, as often is the case in focus groups or a lab-based study.

Gladwell cites a study in which people had the option of understanding others by either going out with them twice a week for over a year (for example, every Saturday night to dinner and out to lunch) or spending just 30 minutes walking through their bedrooms. Of course, both common sense and our bias tell us that spending more time with a person would be much more revealing than just a short visit to his or her bedroom. But the study revealed the opposite: the people who spent only 30 minutes in someone’s bedroom learned and understood more about the person they were evaluating than those who spent time with the actual person. They were able to gather important information about the individual that they might not have ever picked up in a more public, social setting.

This is the result of a double-blindness. We present ourselves to others a certain way, and it’s within our nature to accept another person for what he or she presents. The more time we spend with that person, the more we carry this belief and the harder it is for us to see and accept that person as something different.

This explains why many shows and movies focus on the person with the double identity or the character who leads a double life: Nurse Jackie, Dexter, Don Draper from Mad Men, and even our heroes Batman, Superman, and Spider-Man. We are fascinated by who they present themselves to be versus who they really are—because we all know that we do the same thing in our own way.

This is why, to do it effectively, we must perform laddering in context, that is, when and where the consumer uses the product, makes the buying decision, or uses a service.

Context provides us with a deeper understanding that tells us more than what the person is saying outwardly while we’re conducting the laddering conversation. It’s this information—getting behind what is being said or done—that’s so crucial to a truly successful evaluation.

At this point, I am focusing on evaluating a product or tangible experience. I know that you may be reading this book for marketing messaging and content, and I promise that I’m getting there. To succeed with the marketing message part of the process, you must start with something concrete that the consumer can understand and tell you. People know how to react to concrete questions and ideas; they know how to tell you about their lives and how they lead them, and they can share what’s important to them. Yet most individuals have rarely, if ever, spent time contemplating why these things are important or what the underlying need is they are seeking to fulfill.

By taking the time to truly understand your consumers, you can start speaking to them at a place of understanding. As a result, you can build products, services, messaging, and experiences that resonate with consumers in ways they can’t even explain. Some of the world’s most admired brands, such as Apple, Target, Old Navy, Harley Davidson, and Starbucks, have perfected this by becoming a brand consumers want to hang out with, just like they do with their other friends.

This chapter will provide some practical advice on how to understand your consumer more deeply than you ever have before. I will give you some guiding principles on how to successfully conduct laddering with your consumers to ensure you are getting to a foundational and pure understanding. This advice is relevant beyond laddering—it applies any time you have a conversation with someone—professionally or personally. Always strive to understand what really matters to the other person in a given situation or context.

Step 1: Have a Broad Conversation

Instead of laddering the product by starting with a features or function set, you want to ladder the consumer. So you must start broadly. If you begin by immediately taking a consumer to the product’s feature level, it’s impossible to bring that person out more broadly to understand what really drives him or her in terms of context or choice along the decision journey.

One of the biggest mistakes I see people make with the laddering technique or qualitative research in general is starting too intently focused on the topic at hand. They begin conversations with something like this: “Today, we are going to talk to you about how you choose to travel” or “I want to show you some new concepts for a technology product.” When you narrow the conversation into a particular context from the very start, the consumer immediately starts to play the game and begins performing when answering the questions being posed. The consumer may even start trying to guess the right answer.

Often, a marketing manager or high-level executive wants to get straight to the point, but doing so discounts the consumer before the process has even really begun. There’s an adage that states, “No one cares what you know unless they know that you care.” By starting the conversation broadly, you show you care about the consumer—and you will learn about what comes before and after and what influences the consumer’s decision. The really good, interesting stuff, the things you didn’t expect to hear, might be the very factors that drive the overall adoption, and they are very likely the difference in success or failure.

So spend some time establishing a base. Learn about who consumers are as people; get to know them, what makes them tick, what makes them worry, and who or what influences their decisions. You won’t know if this broad information is important until you start analyzing the data or understanding the relationships between what you are hearing and what the product, service, experience, or solution can offer. But if you don’t collect that information during this process, it’s impossible to go back and gather it cleanly and meaningfully later.

Step 2: Document Their Environment

I begin evaluating a person’s drivers and motivation from the second I pull into their neighborhood or apartment complex and as I walk up to their door or enter their office. I take pictures of their environment. And I use everything that I collect as a clue to whom each person is—and more importantly, who that person wants to be.

I know that I provide the same clues for other people, as do you. As I mentioned earlier, if you visited my office, you would find a collection of Starbucks mugs from all over the world. The average observer might assume that I must really love coffee, especially Starbucks coffee. But what these mugs truly represent is my core desire to travel and love of visiting different places. These mugs have become a barometer for me when I meet a salesperson for the first time. Let me tell you how.

I can tell the difference between a good salesperson and a great salesperson by what that person says about these mugs. A good sales guy will say, “I see that you really like Starbucks.” But a great sales guy notices that the mugs are from all over the place and will ask something more meaningful, such as, “Did you collect those mugs on your trips, or do other people bring them to you?” The mugs are a little bit about coffee and Starbucks; they are a lot about travel, new experiences, and new places. They serve as a reminder of what I really love and what I am ultimately pursuing: the nomadic freedom of a world traveler. A good gift or follow-up for me isn’t about coffee (although I won’t turn away an offer for someone to pay for my habit). I am far more likely to remember a recommendation someone makes for a place to visit or stay on my pursuit to visit everywhere.

Think about the items you collect or keep on your desk or space at work. What do they say about what is really important to you? Even if you answer, “I keep very little in my office” or “My area is sparsely decorated,” that speaks volumes about you as well. It means that you are either (1) not that committed to where you are currently working or (2) have interests elsewhere, something you care about more. You learn as much about others in the absence of participation or information as you do in when they actively participate.

Starting broadly and documenting the consumers’ surroundings allows you to fully understand your consumers and how their environment affects them. Our best interviews are those in which the participant says at the end, “I have no idea what you were asking me about, but I hope I was helpful.” By keeping the first rounds of conversation broad, we can look for what’s really important to the consumer—and what else might be affecting him or her.

Step 3: Talk to Enough Consumers Until You Have Talked to Enough Consumers

The goal here is to understand the patterns in the groups to whom you are talking. I often am asked, “How many interviews do you need to do to accomplish this?”

As I mentioned earlier, the standard answer I give is, “I don’t know what I know until I know it.” And although that might sound like a nonanswer, it’s the truth. If we looked at how we learn anything, that’s the case: we don’t know that we know something until we know it. And until we can describe and explain it to others with confidence, we are still learning.

You need to interview people until you start hearing and seeing repeated patterns. When you can begin to predict what the person is going to say because of what you have learned previously, you know that you’re onto something. When you can explain to others why consumers are behaving a certain way based on a set of certain conditions, you have come to the point of learning and realization.

This might sound ominous, but don’t despair. As long as your context is narrow enough (which is always the case if you work for a specific brand or product), you will likely start noticing patterns between 18 and 27 interviews. This means individual interviews, not interviews with 18 to 27 people in groups (recall the problems with focus groups that we’ve already covered). As previously mentioned, focus groups do have a place and can be done effectively but only after you have a base understanding of who your consumers are and what makes them tick. This initial set of interviews allows you to fine-tune your conversation to learn what parts are important and to determine how many more interviews you need to conduct.

Although these numbers might seem small to the quant-minded, that’s the beauty of this work. I have proven time and time again that the predicted distribution of the clusters taken from a small sample stands true when quantified. Until we get to a point where we are using the right lens to unlock the big data that we’re collecting, quantifying the new connected consumer is going to continue be a tricky proposition unless paired with strong qualitative understanding.

One reason for this is that quantification methods require the consumer to opt in—in other words, to participate. And one of the first things you learn when you begin to ladder your consumers is that certain individuals don’t participate. And if their core behavior is to not participate, why would you expect them to do so in a survey or process that quantifies them? That’s why we must get beyond survey data and counting to an understanding of observed behavior, tone, and intent. This type of information provides a much stronger indicator of who individuals are. Starting with this understanding is a far more compelling reason to collect big data than the mere collection of big data under the assumption that the collection alone will lead to an epiphany.

Step 4: Make Sure You Are Talking to the Right Person (or People)

As you go through the process of laddering, you have to be careful about bias, for example, the paradox of chooser verses user. One can highly influence the other, and unless you know what truly influences the use or buying decision, you may begin working under some inaccurate assumptions.

This was the case when I was conducting a laddering project in the agriculture space regarding tractors. Although one group (the owner) was primarily buying the equipment, another (the operator) was using it. If the buyer was in the room, the operator would always defer to what the buyer said. After all, the buyer was usually the boss and very possibly the owner of the farm or the operation. What could an operator with only a few years of experience possibly know that the boss didn’t? Even if the operator thought he or she knew more, it would be disrespectful to express a differing opinion in that setting.

At the same time, the buyer would lament about having purchased equipment the operators complained was too hard to use. Buyers were unlikely to buy this same tractor or tractor line again if the operators didn’t accept it. Combine this with the fact that buyers didn’t regularly, if ever, actually use the equipment as part of their day-to-day tasks. To get an accurate read of what was important, I had to speak to the operator of the tractor independently of the buyer.

This type of bias occurs in established groups; it’s known widely through the qualitative community. If you are working with a vendor who suggests putting work colleagues together in a room to get to the root of a problem, you need to look for a new supplier.

What people do not recognize or discuss as much is that this same bias exists when performing studies or having conversations with strangers who have just met. If focus group participants discuss their professions, either because they are asked or because the topic comes up as part of the natural conversation, an unspoken pecking order is established. Social norms teach us to take our place. If we realize we are in a room with others who might be smarter, wealthier, or better at something than we are, we naturally defer to the dominant person in the room.

This can occur when studies are performed with two parents in a room; each will try to outdo the other by presenting himself or herself as the better, more informed, protective parent. The contextual information we pick up from studies we’ve conducted on the same topic is far more valuable than what we learn in a pristine environment.

One such study focused on parents’ concerns regarding Internet security; in these situations, the children would usually be somewhere in the vicinity as we carried out the interviews. Mom or Dad would tell us about all of the security measures they had put in place to make sure that they had limited their children’s access to harmful content or social media channels. Meanwhile, the child would be standing in the background, gleefully sharing with us the workarounds they used to avoid the protective barrier their parents had established. One young lady told me that when her parents restricted access at 9 PM each night, she just hopped onto the neighbor’s open network and continued to chat with her friends across Facebook. This is not information I would have gathered by bringing her Mom to a lab facility—and certainly not by putting her Mom in a focus group with other parents. This finding was not the exception either; rather, it became one of the factors that separated parents into different groups.

If you have conducted your laddering work broadly, in the proper context and with the right person, you can explain with finite detail how the clusters relate to each other. I call this process latticing the user groups. I will go into deeper detail later in the book in Chapter 6 about how understanding this relation can help you to both target consumers and create additional reach for the products, services, or experiences you are creating.

Step 5: Keep Your Data and Your Information Clean

Always conduct interviews in pairs to make sure you have more than one point of view. This allows you to capture from both a broad top-down perspective as well as a detailed bottom-up point of view. This approach prevents bias when looking at the data, because one consumer might be especially memorable and affect the impression of the person leading the conversations.

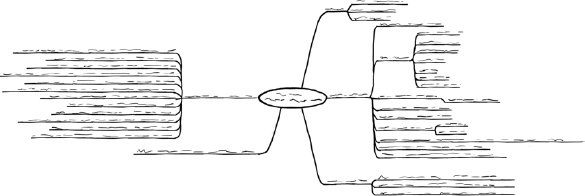

Team members should fulfill different roles throughout this process. One can conduct the interview, while the other takes detailed notes during each and uses a mind map to cluster findings from the notes, as shown in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 Example of a Mind Map of Bottom-Up Data

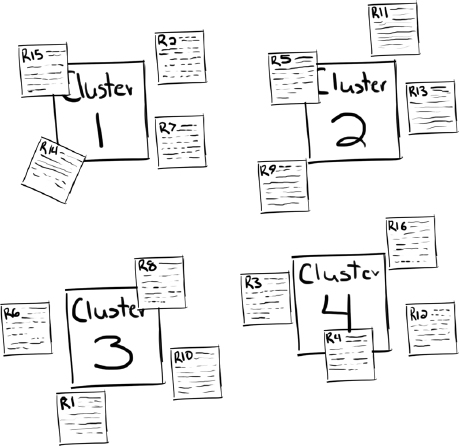

The team member conducting the interviews should work from the top down, coming up with a list of large topics or themes thought to be important based on the interviewing process (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2 Example of Top-Down Patterns

Not only does this dual approach protect the data, but it allows the interviewer to truly focus on the conversation at hand. And the secondary player (the notetaker) keeps the interviewer honest by ensuring that the interviewer covers all of the same ground with each participant. Of course, you don’t need to cover the discussion the same way with each person, because the conversation should flow naturally. However, you do need to pick up the same answers to questions and curiosities either directly or indirectly in your time with the consumer.

Step 6: Keep the Conversation on the Topic at Hand; Avoid Distractions

Money is a good example of a topic that can detract from the root conversation. It’s always a consideration; almost every consumer wants to start a conversation about a product, service, or experience with “depending on the price.” You have to remove that factor from their consideration and get them to talk about what they really care about. Then you can understand how the price might affect their decision. Money affects only how consumers manifest their core. They will find a way to express their core, even if money is currently an issue for them.

We have conducted many laddering projects during economic downturns or uncertainty. As a result, some consumers who worry about how they appear publicly and have a desire to spend as part of their core may not look like they are having any kind of economic issue. But once you get into their house or other private space, you can quickly ascertain what’s really going on.

Again, uncovering the real drivers requires that you understand and involve yourself in the consumers’ context—their homes, offices, or whatever it is—to get a true picture of what’s really going on in their lives. Don’t let them, or yourself, get sidetracked by a limiting factor like money.

Step 7: Your Results Should Make Sense at a High Level

The number of clusters is going to be based on the topic that you are covering, otherwise known as context. You can use this number of clusters or the repeating patterns of answers, context, behavior, or content as a guidepost to check your work.

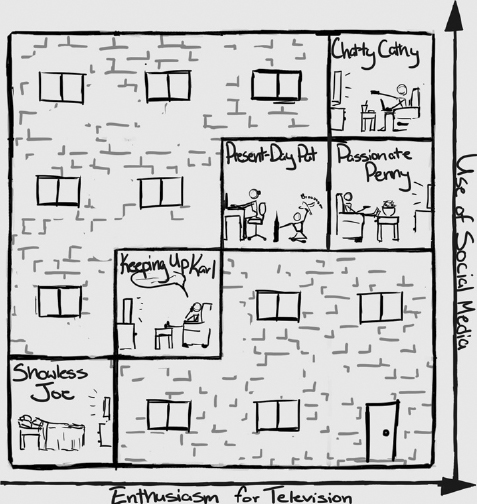

Because the context in my earlier examples of cruising or banking is very small, the number of clusters is also very small: three. The cluster size grows to six in the case of the intersection of social media and TV in the upcoming case study because both of those contexts are very large.

We can use coffee as an example of a good way to think about how many clusters (distinct consumer groups that map to one another because of their core DNA or behavior) might exist. The number of clusters for people who drink coffee would be large, something like seven to nine. The number of people who go out for coffee or buy it on their way into work verses brewing and drinking it at home would be smaller, closer to four to six. And the number of clusters of consumers who stop at a specific type of coffee location would be more like two or three.

Isn’t it great to think that you only really need to manage two or three groups within a discrete brand or experience—and that you can speak to these people in a way that’s really important and meaningful to them? As we move into the next chapter, we will get into the brass tacks of how to perform a laddering exercise that unlocks and uncovers your consumers’ core drivers and behaviors.

- We all wear masks, that is, present ourselves differently in public than we truly are in private or when we’re with those who know us best.

- Have a broad conversation with your consumers to peel away their masks. Start by understanding the person, then move closer in to the product or subject at hand.

- Pay close attention not only to what the consumer tells you but also to what isn’t shared. There are many clues to who consumers are and what is important to them buried in the context of where they live.

- Have enough conversations with consumers until you start to see repeating patterns in the answers. Once you can predict what a consumer is going to say based on that person’s previous answers or contextual clues, you know you are starting to catch on to what’s important to a group.

- Often, companies will focus on the wrong person in the buying or choosing equation. By paying attention to the context you are in and the information you are collecting, you can uncover these biases and consider them when evaluating the results.

- Perform your conversations with consumers in pairs. Have one person focus on collecting information from the bottom and mapping it while the other person thinks about the big picture and works from the top down.

- Avoid introducing information that could skew your results; money, for example, is always a part of the conversation but is rarely the real driving factor behind a consumer’s buying decision.

- The number of clusters you uncover should map to the size of the context. If the topic you are discussing with the consumers is very narrow, you will have only a handful of clusters. A broader topic such as television will have a much larger set of clusters.

Figure 4.3 The Convergence of Social Media and Television Viewing