Chapter 6

Latticing

Finding the Overlap in Ladders

Deep inside us we’re not that different at all.

—Phil Collins

THE FOLLOWING BLOG post was written by Nicole Ovens, one of my colleagues at User Insight, in September 2012. It talks specifically about how social media has helped bridge the gap between individuals. It also supports the notion that we are driven by experiences and issues at our core and looks at how different forces of nurture and nature affect the way we live our lives.

It is just as important to look for these types of intersections, understand why they exist within your consumer groups, and assess how the different clusters interact and act at these intersections as it is to understand each individual cluster’s laddering. This post sums up the difference this latest round of disruptive technology has made to our lives:

We live in an amazing time—one during which social networking has brought attention to health issues that were [once] considered too insignificant to study. [Today’s online interaction has] provided support for those of us who once thought, “Wow, I am so different from everyone else I know.” This digital revolution increased awareness and identified a hidden demand surrounding a health issue that is near and dear to my life.

Thirty years ago, I was diagnosed with celiac disease. It took almost seven years (most of my life, to that point) to discover what was wrong with me. Misdiagnosis after misdiagnosis and invasive test after invasive test and finally . . . the silver bullet: all you have to do is stop eating wheat. Well—wheat, barley, oats, rye, and alfalfa sprouts. That was the advice of the time; [and though it was] simple advice, [it] certainly was not easy.

Back in the early 80s, I had to live with my “special diet.” I also had to say goodbye to my two favorite foods: pizza and Wheat Thins. My mom did her best by making crumbly, bland birthday cakes and packing rice cake and peanut butter (sometimes ham) sandwiches for lunch.

I know correlation doesn’t mean causation, but it’s not a coincidence that life began improving big time right here in the United States starting in 2007. You may ask how I can pinpoint 2007 with such confidence. I can, because, I went to Italy in the fall of 2006. In Italy, every corner farmacia had a gluten-free section and sold over-the-counter “Xeliac” home tests. When in Rome, I learned that all Italian children are screened for celiac. I remember asking myself (and others) why was it that in Italy—where pasta and pizza reign—that people are so aware of celiac disease. I can remember expecting to get ill when I planned that trip—but I never did. I felt great the whole time, because I never once had a meal that was accidentally cross-contaminated with wheat. I also never felt like I didn’t have enough choice, such that I chose to take a risk. I remember coming back home, wishing the United States was so celiac-friendly. It didn’t take long before that simple wish came true.

The very next year, I started hearing that some restaurants in nearby Knoxville [were offering] gluten-free menu items. Then, in 2008, two restaurants in my tiny town of Oak Ridge also opened catering to people with gluten intolerance. Another red-letter day in 2008 happened when Chex cereal, a mainstream brand, started advertising that Rice Chex and Corn Chex were now gluten-free. Prior to all of this the only major brand I remember being so consumer-friendly was Disney—“where all little girl’s wishes come true.”

So what happened to launch this great transformation in 2007? Social networking went mainstream, and took the digital revolution to a whole new level. Online tools proliferated, giving consumers better access to information and an easy way to build communities that broke down geographic barriers and accommodated our busy lifestyles. All of a sudden, patients and parents dealing with hundreds of issues like celiac disease could join virtual support communities, share advice, recommend doctors, and link to news stories and websites with disease information.

Although it’s told from one person’s point of view, there are many players in the story above. And even though each one is participating in different ways and for different reasons, they are all participating in an authentic relationship. Yes, the restaurants and products are making money addressing this need, but they’re doing so based on an awareness of a niche need that they’ve chosen to address. Mayo Clinic researchers estimate that the number of people suffering from celiac disease is about 1 in every 100. Although 1 percent might not seem like enough to warrant a response, it has. In this era of mass customization, addressing this need for those affected and tapping into the goodwill of those who care about them is appropriate and important.

Once you have undergone the laddering exercise and understand what drives each of your individual clusters, you can then take the time to lattice your customer groups. This step will help you identify where they do and don’t overlap, where to focus your efforts, and which initiatives will have the greatest impact. It lets you determine the common starting point for the clusters you seek to reach.

Take into Account Standard Demographics

All of my analysis uses something to indicate a group’s demographic markers, just to see if a pattern exists. Most of the time, the research simply uncovers a propensity for a group to be slightly more male or female. I would say that the split is often more 50/50 on certain markers, our societal norms cause either the male or the female to suppress core tendencies for some of the consumer DNA I have uncovered. For example, one DNA marker is the propensity to project, to let others know about your feelings or emotions. Men have traditionally been raised to learn not to do this. But recent disruptive technology, social media in particular, allows the male who wants to project to do so and to do it without fear of judgment.

Pop culture, digital technology, and entertainment expert Johanna Blakley made this argument in her 2011 TED Talk (www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZR4LdnFGzPk). Blakley spoke specifically about how social media is “the end of gender,” how it allows us to escape the boxes that we’ve been putting ourselves and others in. She argues that shared interests and values are more important than standard demographics.

Once you have laddered your consumers, you get beneath even the most superficial categories of interest and values to an understanding of why. And this is always the crucial question to ask because it allows you to speak to your consumers in a language that is basic to their underlying drivers. Why does a group participate in an interest or have a shared value? What are they trying to accomplish? What is their goal? Are they seeking a connection or correction to something in their past? Are they trying to prevent something in the future? Is it based on expectations or failures from their past?

Applying a layer of standard demographic information as an overlay helps us understand how life circumstances affect a group’s core. For instance, having less or more money might compel a spender to allocate his or her money in different ways. It doesn’t change that person’s core DNA of having a tendency to spend; it just changes the mechanisms of spending and perhaps the items purchased.

Common Consumer DNA

There are several factors that comprise the chains of consumer DNA that I commonly encounter. I call it consumer DNA because it’s the building blocks on which I start to evaluate and determine how the user groups relate to one another.

One of the best things about my work at User Insight is the fact that it has allowed me to focus on becoming a specialist on the end user, or the consumer. When I first started the company, clients often asked if our company specialized in a single industry or concentrated on one type of technology or product offering. Because the company was established and has grown during an incredibly disruptive time, if it had been that narrowly focused, it wouldn’t be in business today. The one mantra, the one unbroken rule that I am sure to follow, is that I always talk to users. I never assume anything about the consumer, and I always pay attention to and advocate for the user’s needs, expectations, and desires.

This approach means that my knowledge is several miles wide and several feet deep, which gives me the unique perspective to see if and how clusters map across industries and experiences. And amazingly, I’ve found that they do. The crucial types of factors are consistently the same; they just show up in different sequence for different contexts.

This consumer DNA is what makes the difference in how you communicate with and between different clusters, and they include:

| Marker A | Marker B | Difference between Markers |

| Know—Is truly educated about a topic or subject thanks to firsthand experience or knowledge. | Doesn’t Know—Doesn’t have firsthand knowledge; relies instead on others to provide the evidence needed to make a decision or judgment. | This is one of the more difficult factors to determine. If a person falls in the category of doesn’t know and project, then that person will share things with others without having firsthand knowledge. This combination of DNA makes the person want to be the first to tell others about new discoveries or information—he or she wants to appear to be the one who knows. However, it’s crucial in this case to understand the true source of the knowledge. Did the consumer actually find the information firsthand? |

| Project—Openly shares aspects of his or her life via social media channels or in person. | Doesn’t Project—Typically takes a backseat; shares only when asked or to affirm others. | Does the person tell others about the details of his or her life openly, or is the person more reserved? A powerful combination I see in consumer DNA is the group that knows and doesn’t project. Others listen when they share, because it’s so rare and out of character for them. The way they share is also very unique; they may simply do so by taking a picture, posting it, and doing nothing more. |

| Willing to Change—Is often seeking change; wants to try the new, untested technologies or experiences. | Not Willing to Change—Has a mantra something like, “If it’s not broken, why mess with it?” Will not move to a new technology or experience easily without prodding. | Is the person open to change? Will the person make accommodations for technology or process in his or her life, or does the person expect the technology to meet his or her needs? Recall from Chapter 4’s case study that Showless Joe is not willing to change during the regular TV viewing season, but as Singular Sam, he will change to participate in Fantasy Football with his friends. |

| Cares about Other’s Opinion—Very careful about what is posted and where; may look for approval from others before posting. | Doesn’t Care about Other’s Opinion—Will say anything to anyone—either on social media or in person—without really considering the long-term impact of words or actions. | Is this person concerned about what others think about what is shared? Does this person conform to external influences about how he or she should dress and act, or is this person content to marching to his or her own drum? Vice Vicky from Chapter 5’s social media family fits into the second category here. She is fine with using salty language and doesn’t seem to acknowledge the impact her current actions will have on her future self. |

| Expects Authentic—Must have experiences that are real and as close to true as possible; enjoys spending time off the beaten path. | Okay with Artificial—Likes things to be predictable or a known quantity. Prefers to go safe places, for example, Disney World or a tourist attraction. | Consumers that crave authenticity must have the experience firsthand. They can’t be told that something is good or simply read a review. If it’s food, they will go to the restaurant to get a taste before talking about it. If it’s art, they must see the actual painting before offering an opinion. On the other hand, people who are okay with artificial are content visiting the same places all the other tourists do and are actually more comfortable with a known experience. |

| Heavily Invested—Is willing to work hard for an end result. | Less Invested—Is seeking the path of least resistance; wants whatever it is to work with as little effort as possible. | This component of the consumer DNA is most likely to change based on the context. Are they willing to go the extra mile to try something out? Or do they give up if the task at hand turns out to be more difficult than expected? If these consumers are very interested in the topic—perhaps their favorite sport or saving money—they’ll likely be willing to spend more time trying to accomplish the task. If it’s something they could care less about, they will move on quickly (especially if it’s difficult to do.) |

| Online—Is more comfortable connecting, maintaining, and nurturing relationships using technology. | In Person—Prefers to spend time with people physically, at a local hangout or a common meeting place. | Is the individual’s idea of interaction more focused around meeting people in person, or is the person more comfortable using technology and social media to stay in touch? The division between a preference for online and offline is a significant DNA marker I see in studies. You must know where your consumer prefers to relate to you. This is especially important to uncover because it is a preference that you cannot change. |

| Has or Seeks Friends Who Are Like Them—Collects or communicates with others who are like them: others who go to their same church, belong to the same clubs, or have the same political affiliation, for example. | Has or Seeks Friends Who Are Not Like Them—Is more interested in meeting new people who come from a differing background or experience. | This DNA marker speaks to the consumer’s acceptance of new things, experiences, and openness to adventure. Who this individual chooses to associate with and seek out as friends is a good indicator of how safe he or she wishes to play it. |

This is by no means an exhaustive list of the different factors that can appear in consumer DNA. However, it does represent some strong patterns I have seen across projects. The factors that are on or off may vary in different contexts, even for the same consumer. You will also notice that none of these markers include items such as money, life stage, or gender. Consumers develop some of these markers as part of their nature (things that have been true about them since they were born) and as part of their nurture (how they were raised and the circumstances they faced throughout their lives).

You can use the major factors that you determine exist within your clusters to start looking for overlap. If you manage multiple brands or experiences within your portfolio, you should analyze the important DNA according to those discrete brands or experiences. You can’t assume the DNA is the same if the brands within your portfolio are different. I will discuss the concept of lensing in more detail in the next chapter. This includes analyzing how people from the outside world truly perceive your brand, which gives you an idea of the attributes that are most important to mapping your clusters. This allows you to build the construct cleanly, without a prejudice toward a brand, experience, or discrete choices. The objective is to understand your consumers for who they are, where they are, and why.

For now, just remember the way that different groups relate to one another is never the same from one context or interaction to the next. You can’t rely on a template or standard construct to present every relationship between groups. It’s crucial that you choose a construct that allows you to explain all of your users within that framework.

Look for Overlap

We all have DNA that overlaps, and laddering works the same way. Once you establish a core understanding of your user groups, you start to recognize which elements are the same between the different clusters. They just won’t be the demographic markers you are used to looking at and using. Instead of paying attention to whether or not a person is male or female, you will look at differences such as, “Does this person project or not?” And, “Is this person interested in authentic experiences, or does he or she like predictability?”

The step of latticing takes a page directly out of the old segmentation or demographic playbook; however, instead of focusing on the attributes that are easily recognizable and part of that old approach—age, sex, gender, income, education, amount of spend, and number of visits—and then looking for patterns, you assess the data you have about your clusters based on their consumer DNA.

Does your consumer cluster care about authentic experiences? If so, your marketing efforts, product, and brand must support their desire to experience things in real life. They must taste, touch, hold, and see whatever you offer for themselves. A digital experience alone isn’t likely to be enough.

Does your consumer cluster need affirmation? If this is the case, make sure your marketing and social media campaigns include a way to acknowledge consumers, especially if they interact with your brand. If you ignore a group that needs affirmation, you’re almost guaranteed to lose them as brand, service, or product champions.

These markers become the new framework by which you can create products, services, and marketing messages and even determine how to provide support.

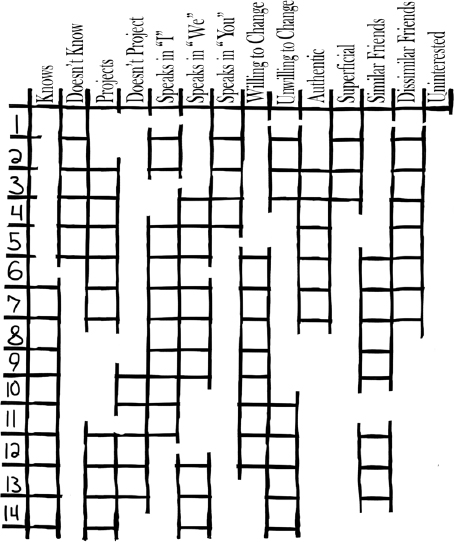

Analyzing overlap is important because it allows you to understand which group(s) to target for a certain product, service, campaign, or experience. It also shows you how various groups influence and interact with one another—in other words, what their ecosystem is. Yes, the ultimate goal is to get your message out to the right person. The thought and associated activities behind rolling out a new idea, brand, or concept is far more important, strategic, and complex than in years past. Latticing your user groups and looking for overlap, developing something that I call a lattice construct, tells you how and where to target for the greatest impact. The added bonus of a lattice construct is it can be used to create a timeline and approach for reaching the other groups (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Lattice Construct

Thankfully, you don’t need the same level of background I have to successfully ladder your consumer groups. You need only to follow this book’s instructions: start by having broad conversations with your consumers, in their environment. Dive deeper to understand your consumers within the context of your industry or focus. You should know your consumers as well as you understand how your company works, how your products are developed, and how your messages are distributed.

Build your product, experience, service, or marketing strategy starting from who your consumers are at their core by developing an understanding of their DNA and accepting that you cannot change them. Rather, you must conform to them.

My experience has taught me over the years that very few companies view their development and marketing efforts in the correct way. It’s far easier for them to assume that they know their consumer groups than to spend a little time to understand what really makes them tick—and why. Very few bother and merely try to build a generalized profile of their ideal consumer through sales reports or a broad understanding.

By spending some time—any time—talking with your consumers and seeking to understand them, you will be much further ahead than most in understanding what really drives consumers in their relationship with your brand, product, service, or company.

Building the Construct

After you have completed the laddering techniques that allow you to understand your individual users, you will instinctively begin to identify what underlying patterns exist and how these patterns define the difference between the groups. At this point, you should test your instinct and include others to help defend or deny your assumptions.

I call this part of the project a war room. Start by hanging all the pictures of the consumers to whom you have spoken on the walls with a bulleted breakdown of what you know about them. Then, begin trying to match them to one another. What makes them the same? What makes them vastly different? How can you explain them succinctly to others outside of the room who have not participated in the laddering exercises? I use all the standard constructs you are probably used to seeing from consulting firms: Venn diagrams, x/y axis charts, and scatterplots. But sometimes I need to depict a very unique relationship. For example, I affectionately called one of our drawings the batwing because it looked like the symbol that Gotham city uses to summon its masked hero.

The visualization process forces you to really think through what you know. I will sometimes attempt an early version during the laddering process between the initial round of laddering and the confirmation round. This helps in beginning to identify the critical factors, may point to additional information I need to pick up, or highlights parts of the laddering process that are not as important within the context.

Recall the bank study I cited in Chapter 2 regarding the word convenience. I was convinced that money was a factor for this project; after all, I was talking with consumers about where they kept their money. But one of my team members disagreed with me and felt that it wasn’t a driver. I realized that it didn’t make sense to apply money as a factor during my attempts to do so in the war room session, so I dropped it. It wasn’t until I tried to explain how the consumer groups latticed that I was able to clearly see it as an unimportant factor even though it was a common theme in the laddering conversations.

Can a Consumer Move between Clusters?

A cluster can’t live in two places. So if your construct is telling you that they do, then something isn’t right, either with your construct or potentially your context (for instance, it may not be narrow enough). You need to be able to explain how, if ever, a consumer moves from one part of the construct to another.

Identifying how and when a consumer moves from one part of the lattice to another is as important as identifying the different groups. This is the most powerful place to intercept a consumer: when that person is in transit. If the consumer is using a competitor’s product, you can convert this person by providing evidence that you will do a better job of meeting his or her needs while they are transitioning.

This is where models like Groupon often fail. Groupon, and other companies, try to convert consumers to new constructs by offering discounted versions of their product, service, or experience. These types of deals speak to one part of the consumer’s DNA, a desire to get a deal or save money, but they are not targeted to the right consumer DNA groups for the brand. Another mistake merchants make is treating those consumers who use the Groupon deal differently than their regular customers. Groupon users can see through this smoke screen; they know that the deal is a temporary change to the brand, not a conscious decision on the brand’s part to move within this new consumer’s core DNA driver. It’s therefore very unlikely that this person will become a new, permanent customer once the deal is done, unless something speaks to his or her core DNA during the experience with the merchant. The consumer sees the execution for what it is: different than what is normally done or delivered. There is rarely a long-term benefit to either party.

We often see a similar phenomenon in our laddering work, called the try it once, never again factor. This explains the success of a gimmick or the concept of viral videos. People want to participate in the trend or the greater conversation when it comes to something that is having its 15 minutes of fame, but it’s not about developing an additional relationship with new consumers. In fact, just like Chatty Cathy, consumers use these types of gimmicks to satisfy something in their core DNA. These stunts are good for temporary uplift; they don’t go very far in terms of encouraging long-term consumer loyalty from the groups that naturally identify with the brand or company attributes. Most of the time, consumers merely remember the video and not the product or brand being advertised.

Using the Lattice for Better Measurement

Latticing not only helps you identify your opportunities for the next new initiative; it also narrows your focus on what is important to measure. You can use the lattice to unlock your big data and make it actionable and useful beyond being just a collection of information on different groups.

For instance, let’s say that you discover that a cluster’s DNA includes a particular strand. In this case, it’s a tendency for them to share how they feel. This group is connected with another cluster that will comment only on what the first cluster shares; however, the second cluster will not share anything themselves. You can measure a campaign or product experience’s success by monitoring the interactions between these two groups. In other words, it’s not about unique likes, shares, or offline conversations; it’s also about others’ reactions to those occurrences, within their own DNA tendencies and behaviors. It’s crucial to view success by measuring it from the consumer’s perspective.

Different groups’ core consumer DNA lets you define the behaviors you would expect to see (or not see) from each. If the cluster is willing to change and likes to project, a technology or experience that supports these preferences and desires, such as the features in Foursquare that allow people to check in to a location and tell others about their experience, will work well. Conversely, this technology will fail miserably with groups that are unwilling to change even if they like to project.

It’s at this point in the process that you can begin to look at your brand, company, experience, or marketing message. Regrettably, this is where most companies start: by talking and thinking about themselves and their brands. By waiting to start this evaluation process until you can view your company, brand, or product through your end user’s perspective, you really learn how to make a difference in how you reach and communicate with your end consumers.

The next chapter explains lensing exercises, a process that helps you identify where you currently stand with your consumers. It’s a valuable way to evaluate everything you consider doing from your consumer clusters’ perspective and it is the most powerful and rewarding part of the consumer-focused laddering process—the payoff for all your work.

- Use standard demographic markers to filter what you have identified in your clusters, but only to understand if a certain marker has a higher likelihood to map to a given demographic.

- There is a common set of consumer DNA, the markers that define an individual and separate clusters into their individual groups.

- By identifying the overlapping DNA markers between clusters, you can understand how your clusters are different and similar.

- Building a lattice construct clarifies these overlaps, gives you a model for explaining them to others, and pinpoints what causes a cluster to move from one part of the construct to another.

- The lattice construct provides valuable insight into unlocking the data you are collecting by providing you with a way to view how the clusters relate to one another and to identify what is truly important to each of the clusters within a context.

- Consumers can and do move between clusters within the construct. This movement is the most powerful time to capture and convert them because they are outside of their core DNA, giving you an opportunity to build something in this transition that will capture them once they return to their core.

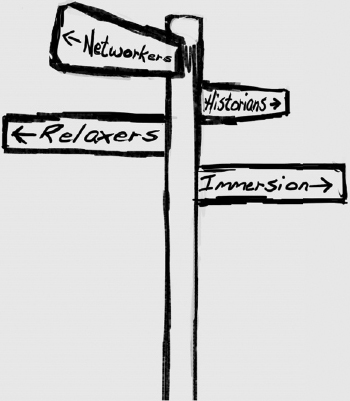

- There is a group that just wants to relax. These consumers wanted to park on a beach and do nothing—make no plans and have no responsibilities.

- Another group of people were traveling to visit friends and family. They usually picked places to visit based on whether they knew someone there, and many had a contact list of friends who lived all over the world. They were really good at keeping in touch with people.

- A third cluster was all about seeking adventure and never wanted to visit the same place twice. They usually wanted to go somewhere unusual and participate in an authentic or local experience while there.

- The last group was interested in history. They gravitate toward locales with historical significance, want to learn everything there is to know about the places they visited, and had a list of must-sees from previous vacations.

Figure 6.2 There Are Four Drivers for the Broad Topic of Travel