Chapter 3

Identifying and Surviving the First Four Stages of Organizational Growth

All organizations pass through various stages of development. These stages are, at least in part, determined by the organization's size, as measured by its annual revenues (or for nonprofits, in terms of annual budget). This chapter presents a framework for identifying and explaining the major stages through which all organizations grow and develop as they increase in size. It should be noted that this framework applies to a division of a large company, as well as to an independent organization.

First, we identify the seven stages of organizational growth comprising the entire life cycle and then, in this chapter, examine the first four stages from the inception of a new venture to organizational maturity. We identify the emphasis on each level in the Pyramid of Organizational Development that is required at each growth stage and explain the nature of the transitions to different stages. Throughout the discussion we will present selected examples to illustrate success and failure at each stage. Then, we discuss the differences between an entrepreneurship and a “professionally managed” organization and what must be done to make the transition between these major growth stages. Next, we present a case study of a company (99 Cents Only Stores) from its inception as a new venture through its transition to become an entrepreneurially oriented, professionally managed organization. Finally, we discuss the keys to success at Stages I to IV. We will discuss the remaining three stages of growth (stages V to VII) in Chapter 4.

Stages of Organizational Growth

Like all things, organizations have a life cycle. Based upon our research, we have developed a life cycle model that identifies seven predictable stages of organizational growth. The seven stages in our model are:

- I. New Venture

- II. Expansion

- III. Professionalization

- IV. Consolidation

- V. Diversification

- VI. Integration

- VII. Decline and Revitalization

The first four stages characterize the period from inception of a new venture or start-up to the attainment of organizational maturity. This period includes the development of an entrepreneurship through the stage when the business becomes a professionally managed organization. Stages V through VII all deal with the period of a company's life cycle after the attainment of organizational maturity through decline and revitalization.

This chapter focuses on the first four stages of organizational growth, because they comprise a complete era of growth from inception of a new venture to early organizational maturity or young adulthood. We return to the last three stages in Chapter 4, which presents the challenges posed to continue success after an organization has reached maturity.

At each of these stages, one or more of the critical tasks of organizational development identified in Chapter 2 should receive special attention. The stages of organizational growth, the critical development areas for each stage, and the approximate size (measured in millions of dollars of sales revenues for for-profit companies and in terms of annual operating budget for nonprofits) at which an organization will typically pass through each stage are shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Stages of Organizational Growth

| Stage | Description | Critical Development Areas | Approximate Organizational Size (millions of dollars in sales) | |

| Manufacturing Firms | Service Firms | |||

| I. | New Venture | Markets and Products | Less than $1 | Less than $0.3 |

| II. | Expansion | Resources and Operational Systems | $1 to $10 | $0.3 to $3.3 |

| III. | Professionalization | Management Systems | $10 to $100 | $3.3 to $33 |

| IV. | Consolidation | Corporate Culture | $100 to $500 | $33 to $167 |

A key word in this statement is typically. What this means is that for approximately 90% of manufacturing firms that have revenues in the range of $10 million to $100 million, they will typically have to encounter the critical issues of Stage III.

There are, however, certain organizations that will have to face these problems at an earlier stage in their development, or much later. For example, there may well be a $3 million manufacturing business that is facing the need to professionalize its management systems. Or a few organizations may well reach $1 billion in annual revenue without really having to face the need to professionalize their management systems. Accordingly, we need to view the relevant range as designated for the transition to occur at each stage of development as a normal curve. In statistics, a normal curve designates the percentage of observations that fall under the area of the curve. This means that statistically 68% of the cases will fall under one standard deviation of the normal curve, while 95% of the cases will fall under two standard deviations of the normal curve. There are, of course, always certain exceptions to this. Similarly, there are exceptions to the revenue parameters used to mark the various stages of growth.

It should also be noted that in Table 3.1 we use two different ranges of annual revenue to designate the various stages of growth. Our experience and research indicate that each stage of growth is reached somewhat earlier for service companies than for manufacturing businesses. This occurs because of the greater complexity of a service company relative to a manufacturing company with the same annual revenues. This is, in turn, caused by the fact that manufacturing companies typically purchase materials that are semi-finished and use them in their manufacturing process. Accordingly, the manufacturing company's revenues include a return for the components of cost of goods sold that are derived from other organization's work. This means that the manufacturing company's value added is less than the comparable value added for a service company at a given size of annual revenues. This does not mean that the manufacturing company makes a lesser economic value-added contribution than a service company; it merely means that the service company with more employees and no raw materials to be recouped as part of sales revenue has a relatively more complex operation than a comparably sized manufacturing company.

As a result of this phenomenon, we have found it useful to convert a service company's revenues into the comparable units of those of a manufacturing company. This process is similar to the conversion from the imperial system to the metric system or from dollars into any foreign currency. Thus to convert a service company's revenues into comparable units of a manufacturing company, we multiply the service company's revenues by a factor of 3 (as reflected in the figures shown in Table 3.1). This means that the typical service company is three times more complex to manage than a comparably sized (in revenues) manufacturing company. Alternatively, it means that a $5 million service company is the rough equivalent of a $15 million manufacturing company. It should be remembered that this is an experienced-based adjustment that we have found useful rather than a strict formula.

Most nonprofit organizations can be classified as service organizations (providing services or funding for services to specific populations). Further, many nonprofits—particularly foundations, charities, and organizations that are government-funded—do not have any revenue per se. In these cases, the organization's annual operating budget can be used as a surrogate for revenues. The budget, in this case, represents the size and complexity of the business, in terms of clients served, projects funded, and so on. We focus specifically on the growth and development of nonprofits in Chapter 11.

In the following discussion, for convenience, we refer to an organization at a given stage using the parameters for manufacturing companies as a base. The reader can adjust for service companies by using the service company adjustment factor of 3, or can simply refer to Table 3.1. Financial institutions, such as banks, savings and loans, and mutual funds, can be viewed as service companies under the framework. Distribution companies can be viewed as a hybrid manufacturing-service organizations, and a multiple of 2 can be used as an adjustment factor. (In other words, a $5 million distribution company is the same as a $10 million manufacturing company and is, therefore, nearing Stage II of its development.)

Stage I: New Venture

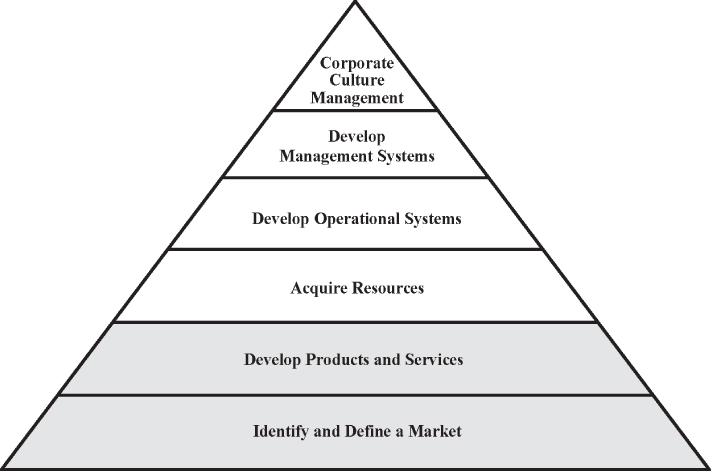

Stage I of organizational growth involves the inception of a new venture. Stage I typically occurs from the time an organization has virtually no sales until it reaches approximately $1 million in annual sales for a manufacturing firm (or $0.3 million for a service firm). During Stage I, the organization has to perform all the critical tasks necessary for organizational success, but the greatest emphasis is on the first two tasks: defining markets and developing products. This is represented schematically in the organizational development pyramid shown in Figure 3.1. These two tasks are critical to the organization's survival because without customers and products or services to provide to them, it simply cannot exist. The ultimate purpose of this stage is to establish proof of the business concept.

Figure 3.1 Developmental Emphasis in a Stage I Organization

Many businesses have succeeded as new ventures because the entrepreneur was able to identify a viable market and product. For example Brian and Jennifer Maxwell, both runners, created PowerBar first for their own personal use as a source of competitive advantage, and then developed it into a business. This product led to the creation of an entire new category—the energy bar category.

Similarly, Jerry and Goldie Lippman, the founders of GOJO Industries (the inventor of PURELL® hand sanitizer) saw the need for something that would serve as a hand cleaner and sanitizer. The idea for the company's first product came from Goldie while she was working in one of Akron's (Ohio) rubber plants during World War II. Many of the traditional male rubber workers had gone off to war, and the women who replaced them needed a better way to remove dirt from their hands than the harsh industrial chemicals used at the time. Jerry, with only a 10th grade education, sought out chemistry professor Clarence Cook at Kent State University, and together they invented a product that would remove dirt without irritation. This was sold as GOJO® Hand Cleaner, and the couple's first customers were Goldie's co-workers in the rubber factory. With Goldie handling administrative matters, Jerry began selling to automotive service and manufacturing distributors and, within a few years, a new product category, heavy-duty hand cleaner, was established. The market remained small because of the high cost of the product, relative to the “free” cleaning solvents readily available. Jerry solved this problem by developing a portion-control dispenser and adopting a razor/razor blade approach to placing dispensers and selling proprietary refills. Today, GOJO is the world leader in institutional hand hygiene and healthy skin.

Other examples of new ventures that came about when an entrepreneur perceived a market need to be served include Noah's Bagels (fresh bagels of the highest quality in the western United States), Federal Express (overnight delivery of packages and mail), and Google (an online search tool that would enable customers to quickly find and use information).

Once in a while, a new “transformational technological platform” emerges that can be “leveraged” by entrepreneurs or existing organizations to create a plethora of new ventures. The Internet is such a platform. It has helped spawn many new ventures including Amazon.com, Facebook, Netflix, and Alibaba. For example, Netflix and Amazon.com leveraged the Internet to enable anyone with access to the Internet to see a movie or other media content at any time.

Many other new ventures are reasonably successful and profitable but not as famous or glamorous. They include businesses engaged in executive search, landscape design, printing, financial planning, restaurants, graphic design, repair services, catering, equipment leasing, specialty retailing, and many more fields. An example of one of these new ventures is EEZYCUT, founded by David Jones and Laura Mayes.1 David was university-educated and had even completed an MBA degree course while working for Bayer PLC. Looking back, David could see that he was not yet mature enough for a commercial life and still describes himself as a cave diver (explorer) and social drop-out.

David perceived the need for a new type of cutting tool that divers could use. The old style diving knife then in use rusted immediately and blunted quickly. While on a “deco stop” (which is a pause while rising to eliminate dissolved inert gases from the diver's body and avoid the bends), David pondered how to make a better device than the one offered at the time. The first design was a failure, and David found himself starting again. It was a simple engineering design that resolved the problem with the first cutting device and made the new device (the Trilobite diver's knife) an attractive choice for emergency cutting tools. The Trilobite was the first on the diving market that provided exchangeable blades for the consumer.

David had designed an emergency cutting tool that was intended for use by divers. However, other non-divers saw the knife and found it had many other applications. This led to another design called QuattroPod, aimed towards emergency rescue services. EEZYCUT's Trilobite has been used by skydivers, hang-gliders, paragliders, kayaking, fire and rescue services, fishermen, yacht owners, gardeners, prison guards, special forces, ski patrol, public safety officers, emergency room workers and paramedics, as well as scuba divers. It has also been used in animal rescue of marine life caught in fishing line!

While David focused on the design and deal aspects of the business, Laura's role was ubiquitous. Laura was involved in the business with David from its conception. Since they are married, the business relationship developed through physical proximity. Their apartment was full of boxes and sewing machines. Laura took the phone calls, read the emails, paid the bills, and shipped the product. According to David, “Laura pretty much did everything, and kept the ship running” while he barked orders at her from behind the machines. Also, David is a self-described hermit, and Laura was his only sounding board. So she was fully informed and involved in strategy, business direction, contracts, and so on. They are a working partnership as well as a family. With no prior distribution experience, the pair has built their company into a Stage II business selling the EEZYCUT Trilobites around the globe.

Entrepreneurs do not always have to be first to identify an unserved market segment. Often they can enter a market with a better product or service. The classic example of an entrepreneur who succeeded after others failed is Herb Kelleher, founder and former CEO of Southwest Airlines. Although others had identified the market for low-cost airfare, Kelleher was the first to find the successful formula for low-cost, no-frills airfare—a market segment that Southwest has grown to dominate. Coffee is certainly not a new product, but Starbucks has grown to dominate the retail coffee bar segment. Although girls have played with dolls for many decades, if not throughout history, Isaac Larian, founder of MGA Entertainment, created Bratz Dolls to appeal to “tween” girls and grew his business to one of the largest toy companies in the world.

Keys to a Success at Stage I. At stage I, the two keys to success are the ability to identify a present or potential market need (defining a market) and the ability to develop a product or service that will satisfy that market need on a profitable basis. Taken together, these two things are necessary to establish proof of concept.

Stage II: Expansion

If an organization successfully completes the key developmental tasks of Stage I, it will reach Stage II, which involves rapid expansion in terms of sales revenues, number of employees, and so on. For most manufacturing firms, Stage II begins at about the $1 million sales level and extends to the $10 million level. (For service firms, this stage typically begins at approximately $0.3 million and continues through $3.3 million in revenues.)

Stage II presents a new set of developmental problems and challenges. Organizational resources are stretched to the limit when increasing sales require a seemingly endless increase in people, financing, equipment, and space. Similarly, the organization's day-to-day operational systems for recruiting, production or service delivery, purchasing, accounting, collections, information, and payables are nearly overwhelmed by the sheer amount of product or service being “pushed out the door.”

The major purpose or challenge of Stage II is “organizational scale-up.” This means that the business concept has been demonstrated to be valid (Stage I), and the organization must now acquire the resources and develop the systems required to facilitate growth. For example, EEZYCUT (described earlier) is beginning Stage II. Its founders, David Jones and Laura Mayes (husband and wife) are currently in the process of what they term “upgrading” the infrastructure of EEZYCUT to better handle the challenges they face in Stage II of their business. As David states, “It is a lot to handle!”2

The major problems that occur during Stage II are problems of growth rather than survival. It is during this stage that horror stories begin to accumulate:

- Salespeople sell a product they know is in inventory, only to learn that someone else has grabbed it for other customers.

- One vendor's invoices are paid two and three times, while another vendor has not been paid in six months.

- A precipitous drop in product quality occurs for unknown reasons.

- Turnover increases sharply just when the company needs more personnel.

- Missing letters, files, and reports cause confusion, loss of time, and embarrassment.

- Senior executives find themselves scheduled to be in two widely separated cities on the same day at the same time, or they arrive in a distant city only to learn that they are a day early.

- The computer system crashes frequently, leaving users without access to valuable information, basically shutting the company down for hours or sometimes days.

These are what we call growing pains.

The classic organizational growing pains that are typical of Stage II and later-stage companies are discussed in detail in Chapter 5. The relative emphasis on each key developmental task appropriate for Stage II is shown schematically in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 Developmental Emphasis in a Stage II Organization

Many companies experience a great deal of difficulty during Stage II and even disappear. Although it is established that 50% of companies survive until stage II, there are not sufficient data on the percentage that survive until Stage III. We believe (or hypothesize) that about 50% of the original 50% surviving companies at Stage II will again survive to stage III. This means that 25% of the original start-ups will survive until Stage III.

When failure at Stage II occurs, it is usually because the founding entrepreneur is unable to cope with the managerial problems that arise as the organization grows. A Stage II company needs an infrastructure of operational systems that lets it operate efficiently and effectively on a day-to-day basis. Unfortunately, many entrepreneurs are not interested in such organizational plumbing.

Some businesses that are fortunate enough to have discovered an especially rich market find themselves growing very rapidly. Although most of the development of resources and operational systems ought to occur during the period when the organization is growing from $1 million to $10 million in annual revenues, it is not unusual to find companies with $30, $40, $50, or even more than $100 million in annual revenues with the operational systems of a Stage II organization. This kind of discrepancy between an organization's size and the degree of development of its operational systems leads to serious problems, but these may be masked in the short term by rapidly rising revenues. This often proves to be the case in some of the most spectacular examples of organizational failure, such as Osborne Computer.

Today the name “Osborne Computer” is largely unrecognized, except by “Boomers.” Yet it was once as high-profile as Apple or Starbucks. Adam Osborne was an entrepreneur who perceived the need for “portable PCs,” which are now known as “laptops” (even though his product weighed 28 pounds and had a screen about 6 inches wide). He developed a company, which grew to $100 million in revenues within two years, but then went bankrupt in its third year. It was a classic example of meteoric success followed by meteoric failure, brought about, at least in part, by underdeveloped operational systems. In an article on the rise and fall of Adam Osborne, Steve Coll states, “In retrospect, it seems clear that the company's accounting procedures were so slipshod that no one knew how things were.”3

The lesson of what happened to Osborne and his fleetingly successful company needs to be learned by all entrepreneurs. Many companies continue to make the same mistakes, and the end results are similar. For example, system crashes experienced by several online brokerage firms are a warning that both the product and related infrastructure are not sufficiently developed to serve as a sound platform for future growth.

Since rapid growth can create problems as well as opportunities it is essential to be prepared for it. Preparation for growth typically requires the acquisition of resources of various kinds including money, people, and equipment. It means the development of the day-to-day operational systems to do what the business is in business to do. We term this the “operational infrastructure,” which refers to the resources and day-to-day systems required to operate the business.

Keys to Success at Stage II. The keys to success at Stage II are fundamentally different from those at Stage I. Stage II is all about expansion or scale up, and successful scale up requires operational infrastructure. The level of infrastructure needs to match the size of the company as measured by its revenues. It also needs to be designed so that it will support the organization's continued growth. If the required infrastructure is in place, the organization will operate well; if not, it will experience a variety of organizational problems, which we term “growing pains.” Growing pains are described further in Chapter 5.

Stages I and II Together

Taken together, Stages I and II—the new venture and expansion stages—constitute the entrepreneurial phase of organizational development. It is during these two stages of growth that the classic skills of entrepreneurship are most relevant. It is also during this phase that the need to make the transition from an entrepreneurship to an entrepreneurially oriented, professionally managed organization begins to occur.

Stage III: Professionalization

Somewhere during the period of explosive growth that characterizes Stage II, senior management realizes (or ought to realize) that a need for a qualitative change in the organization is arising. The company cannot merely add people, money, equipment, and space to cope with its growth; it must undergo a transition or metamorphosis and become a somewhat different type of organization.

Until this point, the enterprise generally will have been totally entrepreneurial. It has operated with a considerable degree of informality. It may have lacked well-defined goals, roles, plans, or controls but still prospered. However, once a critical size has been achieved, many of these practices and procedures must be increasingly formalized. The need for this transition typically occurs for manufacturing organizations by the time they have reached approximately $10 million in sales. (For service firms, the need for this transition typically arises when they have reached $3.3 million in revenues.) At this level of revenues, the sheer size of the organization requires more formal planning, regularly scheduled meetings, defined organizational roles and responsibilities, and performance management systems. The people who manage the company and its operations must also change their skills and capabilities. Until this point, it was possible to be more of a doer or hands-on manager than a professional manager. At this stage, however, the organization increasingly requires people who are adept at formal administration, planning, organization, motivation, leadership, and control. In brief, the focus at this stage of development should be on developing the management systems required to take the organization to its next stage of development. Developing and implementing these systems, in turn, requires a planned program of organizational development. It also requires using the managerial tools described in Chapters 6 to 9.

It is at this stage that the company must make a transition from an entrepreneurship to an entrepreneurially oriented, professionally managed organization. This means that the organization, while still maintaining its entrepreneurial spirit, will also need to develop the infrastructure and professional management capabilities required to continue its growth successfully.

This is a delicate balancing act. An organization must never lose its entrepreneurial mindset or spirit, but it must begin to develop the infrastructure and management systems required to facilitate its future growth. Although some people equate professional management with bureaucracy, we believe they are mistaken. It is true that if professional management exists without an entrepreneurial mindset or culture, it can become bureaucracy. But it is also true that if entrepreneurship is carried to an extreme in large companies, it can result in chaos, and chaos ultimately leads to organizational difficulties and even bankruptcy.

As we discuss throughout the remainder of this book, making the successful transition from an entrepreneurship to a professionally managed organization requires some delicate surgery. At this point, the key thing we want to point out is that, based on our research and experience, this transition is not a choice but a requirement or imperative for continued organizational success and that it involves the development of management systems. We shall provide examples throughout this book of both organizations that have made this transition successfully and thrived, as well as others that have failed to make this transition and experienced great difficulties (such as Osborne Computers and Boston Market).

The relative emphasis on each key developmental task appropriate for Stage III is shown schematically in Figure 3.3. As the figure indicates, the most important task during this stage is the development of management systems.

Figure 3.3 Developmental Emphasis in a Stage III Organization

Although the professionalization and related development of management systems of an organization ought to occur during the period when sales are growing from $10 million to approximately $100 million, the rate of growth often outstrips the rate at which the enterprise's management systems are developed. This can lead to serious problems, which can either limit the potential development of a business or cause failure. This was the case at Starbucks Coffee Company in 1994.

At that time, Starbucks was essentially a Stage II company in the process of making the transition to Stage III (in terms of its organizational infrastructure), even though its corporate revenues were more than $100 million (Stage IV). As a result, the business was beginning to experience significant growing pains, which could have hampered the company's development and ultimate success.4

Similar problems occurred at the same stage of growth at Jamba Juice, Noah's Bagels, and PowerBar. Other examples include Apple Computer (revenues of more than $2 billion in 1985 but only Stage II in terms of infrastructure) and Maxicare (revenues of about $1.8 billion). Apple lost market share to IBM, and Maxicare had to downsize and ultimately file for bankruptcy. This company had grown rapidly through acquisitions but had not taken the time to develop an operational and management infrastructure that would support the much larger organization that it had become.

As noted in Chapter 1, the entrepreneurial personality can be a barrier to success at Stage III. Making the transition from an entrepreneurship to professional management involves more than just the development of operational and management systems. It requires a profound mindset change on the part of people, especially the entrepreneurs who founded the company. We have been working with companies to help them make this transition for nearly 40 years. One of the classic obstacles to this process is typically the entrepreneur; many fear becoming bureaucratic, and then confuse bureaucracy with systems. Some of this is deeply rooted in their personalities; they do not want to be controlled by anyone or anything—not plans, not role descriptions, not policies, not procedures.

Because they have been successful in launching a new venture without these things, they assume (either explicitly or implicitly) that they are not necessary and that they are, in fact, barriers to success. What they fail to realize is that the game needs to be played differently at different stages of the organizational life cycle. Without systems or plans or role definitions, the organization will definitely experience increasing confusion and quite possibly chaos. In spite of what one author has written, no one thrives on chaos indefinitely!5

As noted in Chapter 1, when Orin Smith (then CFO of Starbucks) invited one of the authors to work with Starbucks Coffee Company to assist them in making the transition to professional management, he stated that the biggest challenge would be getting Howard Schultz to buy in to the concept that a firm could be better managed without losing its entrepreneurial spirit. He cautioned that Schultz might not have the patience for much process and systems. In fact, Howard Schultz embraced these notions very quickly. They were consistent with his belief that if you are going to build a large building, you need a strong foundation.

This issue of the psychological acceptance of the need to transition from early-stage entrepreneurship to professional management is a traumatic one for many, if not most, entrepreneurs. It requires a leap of faith because their early experiences suggest that systems are not essential to success. Without making this leap, however, the entrepreneurs may put what they have built at risk of decline or even failure.

While some entrepreneurs resist the changes required to transition to professional management, there are others who readily embrace this notion. Among those who readily embraced the idea of transitioning to professional management are:

- Brian Maxwell, founder of PowerBar

- Yerkin Tatishev, founder and CEO of Kusto Group (Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine, Vietnam, and Israel)

- Tim and Jud Carter, Bell-Carter Foods, Inc.

- James Stowers, Jr., Founder of American Century Investments

- Melvin and Herbert Simon, Simon Property Group

One of those cited above was James Stowers, Jr. (now deceased), founder of what is now American Century Investments. The experience of American Century Investments and its founder James Stowers, Jr., in making the transition to professional management is an excellent example of how this process can be done successfully. It is described in detail in Chapter 13.

Keys to Success at Stage III. In summary, the keys to success at Stage III are (1) the ability to recognize the need to transform from an early-stage entrepreneurial venture to an entrepreneurially oriented, professionally managed organization; and (2) the ability to develop the managerial capabilities and management systems required for future sustainable growth, including all of the tools to be described in Chapters 6 to 9. Chapters 6 to 9 also present case studies of how leaders of Stage III and beyond organizations developed and used these tools to support continued success.

Stage IV: Consolidation

Once the organization has made the transition to professional management—with workable systems for planning, organization structure, management development, and performance management—leadership must turn its attention to an intangible but nevertheless real and significant asset: corporate culture. Management of the corporate culture is the main task of Stage IV of organizational development.

The key challenge at Stage IV is to help consolidate or institutionalize the cultural aspects of the transformation from an entrepreneurship to a professionally managed organization. As the organization makes the transition required of Stage III and develops management systems, a cultural transition is also in progress. The company is going from a very loose, free-spirited organization to a more disciplined one; from an organization with a strategy and perhaps a plan to one with a well-defined planning process; from one with vague goals to more specific, measurable goals; from one with loosely defined roles to one with more formal role descriptions; and from one with limited accountability to one with more accountability. Explicitly or implicitly, this involves a cultural change, and it is a change that must be managed if the transition is to be made successfully.

Corporate culture can have a powerful effect, not only on day-to-day operations but on the bottom line of profitability as well.6 During the growth that was necessary to reach Stage IV (which typically seems to begin at about $100 million in sales for manufacturing firms), the organization has brought in new waves of people. The first wave probably arrived when the organization was relatively small and informal, during Stage I. During this period, the organization's culture (values, beliefs, and norms) was transmitted by direct day-to-day contact between the founder and personnel. The diffusion or transmission of culture was a by-product of what the organization did. Virtually everybody knew everybody else. Everybody also knew what the company wanted to achieve and how.

During Stage II, the rapid expansion of the enterprise most likely brought in a second wave of people. The first-wave personnel transmitted the corporate culture to this new generation. However, at an increased level of organizational size, especially if the organization develops geographically separate operations, this informal socialization process becomes more attenuated and less effective. The sheer number of new people simply overwhelms the socialization system.

By the time it reaches $100 million in revenues, a third wave of people usually has joined the organization, and the informal socialization is no longer adequate to do what it once did so well. At this stage, leaders must develop a more conscious and formal method of transmitting the corporate culture throughout the organization, monitoring it and managing it. This is the key challenge faced by Stage IV organizations. The relative emphasis on each key developmental task appropriate for Stage IV is pictured in Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4 Developmental Emphasis in a Stage IV Organization

Keys to Success at Stage IV. In summary, the keys to success at Stage IV are (1) the ability to change the corporate culture or mindset to support the professionalization of the enterprise; and (2) the ability to develop effective systems for communicating, managing, and reinforcing the culture. Chapter 10 examines the management of corporate culture in greater detail and presents examples of companies that have done it successfully and unsuccessfully.

Differences between Entrepreneurial and Professional Management

Stages I and II, taken together, make up the entrepreneurial phase of organizational development, while Stages III and IV make up the professional management phase. As an organization passes from one of these phases of growth to the other, a variety of changes need to occur. There is a qualitative difference between an entrepreneurship and a professionally managed firm. The former tends to be characterized by informality, lack of systems, and a free-spirited nature. The latter tends to be more formal, to have well-developed systems, and to be proud of its disciplined, profit-oriented approach.

The most important differences between an entrepreneurship and a professionally managed organization involve nine key result areas: (1) profit, (2) planning, (3) organization, (4) control/performance management, (5) management/leadership development, (6) budgeting, (7) innovation, (8) leadership, and (9) culture. Table 3.2 summarizes the principal characteristics of professional management, as compared with entrepreneurial management in each of these key result areas. We now describe these differences in greater detail.

Table 3.2 Comparison of Professional Management and Entrepreneurial Management

| Key Result Areas | Professional Management | Entrepreneurial Management |

| Profit | Profit orientation; profit as explicit goal | Profit as a by-product |

| Planning | Formal, systematic planning:

|

Informal, ad hoc planning |

| Organization | Formal, explicit role descriptions that are mutually exclusive and exhaustive | Informal structure with overlapping and undefined responsibilities |

| Control/Performance Management | Formal, planned system of organizational control, including explicit objectives, targets, measures, evaluations, and rewards | Partial, ad hoc control, seldom with formal measurement |

| Management and Leadership Development | Planned management development:

|

Ad hoc development, principally through on-the-job training |

| Budgeting | Management by standards and variances | Budget not explicit; no follow-up on variances |

| Innovation | Orientation to incremental innovations; willingness to take calculated risks | Orientation toward major innovations; willingness to take major risks |

| Leadership | Consultative or participative styles | Styles varying from very directive to laissez-faire |

| Culture | Well-defined culture | Loosely defined, “family”-oriented culture |

Profit

In a professionally managed organization, profit is an explicit goal; it is planned, rather than being a residual or whatever is left over at the end of the year. In an entrepreneurial organization, profit is sought, but it is not an explicit goal to be attained. The entrepreneur may be willing to invest and sacrifice current profits for a future big hit.

Planning

Unfortunately, in many entrepreneurial organizations, the plan, if there is one, is in the entrepreneur's head. A professionally managed organization has a formal, written business plan. Planning becomes a way of life as the organization's leaders develop and use a formal, written strategic plan as the “roadmap” for success. In addition to strategic planning, operational plans and budgets are developed. Contingency plans also are developed. The practice of informal, superficial, ad hoc planning is replaced by a regular planning cycle.

Organization

An entrepreneurial organization has an informal organizational structure with overlapping and undefined responsibilities. People are expected to do whatever is necessary, without regard to job titles or positions. This is fine when a company is small. But as it grows, chaos can set in, with people simply not knowing what they are supposed to do. A professionally managed organization has a set of written role descriptions that clearly state responsibilities. These descriptions are designed to be mutually exclusive and exhaustive. They are intended to help people understand what their roles are and to give focus to their efforts and use of time. There is also a formal organizational chart that accurately provides information about reporting relationships and helps people understand how this structure should work.

Control/Performance Management

In an entrepreneurship, control of operations tends to be lacking or at least is often piecemeal. The organization usually lacks formal measurement or performance appraisal systems. A professionally managed organization, by contrast, has a formal, planned system of organizational control or performance management. This system makes full use of explicit objectives and goals, measurements of performance, feedback, evaluation, and rewards.

Management and Leadership Development

Management and leadership development is planned in a professionally managed organization. There is a conscious, planned effort to develop the managerial and leadership skills of individuals and to prepare a pool of managers that will help take the organization into the future. In an entrepreneurship, however, management and leadership development is unplanned and tends to occur, if at all, through on-the-job experience. Although the entrepreneurial organization may avoid the cost of management development programs, people may become victims of the Peter Principle (being promoted beyond their competence) and cost the company through inefficiency, mistakes, and replacement costs.

Budgeting

In an entrepreneurship, budgeting tends to lack detail. There is little follow-up on variances or deviations from the budget. A professionally managed organization's budget system focuses on standards and variances. Managers are held accountable for performance, compared against budget goals. Budgets are not cast in concrete but are there to guide performance.

Innovation

By definition, entrepreneurial companies are oriented toward innovation. Many are willing to make major innovations in products, services, or operating methods. Some entrepreneurs even “bet the company” on an innovation because of the possibility of a high payoff for success. They tend to need quick hits, or fast payoffs. Professionally managed organizations tend to be oriented more toward incremental innovations. They are less likely to bet the company, and they often spread their risk among a portfolio of different products or projects. They are willing to take calculated risks, but they may seem relatively averse to risks, at least in comparison to entrepreneurial companies. There are exceptions to this, and established professionally managed companies such as Boeing and IBM are famous for having bet the company on new technologies a number of times during their history. Many of the best-managed companies, however, are oriented to continuous, incremental improvements and long-term support of major innovations that do not require fast payoffs.

Leadership

In entrepreneurial companies, leadership typically ranges from very directive styles such as autocratic or benevolent autocratic to very nondirective styles such as laissez-faire. In a professionally managed organization, the tendency today is toward more interactive styles, such as consultative and participative management, or, in a few instances, to consensus or team-oriented styles. Entrepreneurial organizations are more likely to have charismatic leaders than are professionally managed companies because of the nature of the process of selection for promotion in large organizations.

Culture

Culture tends to be loosely defined in entrepreneurial organizations and sometimes it is not explicitly managed. Often the culture of an entrepreneurial organization is oriented toward a family feeling, which is feasible because of its relatively small size. Professionally managed organizations are more likely to treat organizational culture explicitly as a variable to be managed and transmitted throughout the enterprise. They tend to understand that culture is a source of sustainable competitive advantage.

Relevance of Differences

Our discussion of the differences between entrepreneurial and professionally managed organizations is intended to be descriptive rather than evaluative. Both types of organizations have strengths and limitations. The significant point is that different ways of operating are appropriate at different stages of organizational growth.

From an entrepreneurial organization's standpoint, it is clear that something inevitably will be lost as the organization makes the transition to professional management. However, something will also be gained. Just as a plant that has been successful in its pot must be transplanted if it is to continue to grow and develop properly, an organization that has outgrown its infrastructure and style of management must also make a transformation. Failure to do so will lead to a variety of problems.

Discrepancies between Growth and Organizational Development

As we have seen, two independent dimensions are involved in each stage of organizational growth: (1) size and (2) the extent to which the enterprise has developed the systems required to support its size in each of the six critical development areas included in the Pyramid of Organizational Development. An organization can be at Stage III in terms of size, as measured in annual revenues, but only at Stage II in its internal organizational capabilities. In other words, its infrastructure is not developed to the extent that it needs to be to support the enterprise's size. For example, after only a very few years of existence, Osborne Computer was a Stage IV company in size, but it was only a Stage II company in terms of its infrastructure. The lack of infrastructure to support the firm contributed to significant problems, which ultimately resulted in the firm filing for bankruptcy.

An organization will face significant problems if its internal development is too far out of step with its size. As shown in Figure 3.5, the greater the degree of incongruity between an organization's size and the development of its infrastructure, the greater the probability that it will experience organizational growing pains (the topic of Chapter 5). Such an organization is like a 12-year-old boy who is well over six feet tall: He has the body of a man but, most likely, the mind of a child. As a senior manager in one organization stated, “We are essentially a $30 million company that happened to have $350 million in sales.” The manager meant that the firm had the operating systems and developmental structure of a $30 million company, but its growth had given it revenue that greatly exceeded (by more than 10 times) its infrastructure's capacity. Predictably, the company was in difficulty and was ultimately purchased by a competitor.

Figure 3.5 Causes of Organizational Growing Pains

Managing the Transition between Growth Stages

What can management do to help make the transition required between growth stages? There are four steps by which the senior managers of a growing enterprise can help their company make a smooth transition from one stage of growth to the next and, ultimately, make the transformation from an entrepreneurship to professional management. They are as follows:

- Perform an organizational evaluation or assessment of the company's effectiveness at its current stage of development.

- Formulate an organizational development plan.

- Implement the plan through action plans and programs.

- Monitor the programs for effectiveness.

We now examine each of these steps in detail.

Perform an Organizational Evaluation or Assessment

An organizational evaluation or assessment consists of systematic assessment, by means of data analysis and interviews with organization members, of the extent to which systems are adequate to meet the company's current and anticipated future requirements. While this evaluation may be performed by the organization's management team, many companies prefer to have independent consultants conduct the assessment in order to obtain greater objectivity or benefit from their experience with similar companies facing similar issues. The findings of the evaluation represent a diagnosis of the organization at its current stage of development. This assessment might include administering and using results from surveys, such as the Organizational Effectiveness Survey© described in Chapter 2 and the Growing Pains Survey (which will be described in Chapter 5).

Formulate an Organizational Development Plan

Once the organizational evaluation has been completed, management must develop a master plan or blueprint for building the capabilities needed for the organization to function successfully at its current or next stage of development. This is the strategic organizational development plan, which will be described in Chapter 6.

Implement the Organizational Development Plan and Monitor Its Progress

The third and fourth steps in helping an organization make the transition to a new growth stage are implementing the changes set forth in the organizational development plan and monitoring their effects. This includes both developing new organizational systems (planning, organization, and performance management) and developing management's capabilities through corporate education programs. Management development programs may focus on administrative skills (such as planning), leadership skills, or both. We examine the development of these management systems and capabilities in Part Two of this book. Once the development program has been implemented, management needs to monitor its progress in meeting developmental needs. Such monitoring helps senior managers identify and address any problems related to achieving organizational development goals.

These four steps—diagnosing, planning, implementing, and monitoring changes in organizational capabilities—are the keys to making a smooth transition from an entrepreneurship to a professionally managed enterprise. The steps are the same regardless of the size, industry, or current stage of development of an organization. As such, they can also be applied to organizations that have grown beyond Stage IV.

It should be noted that these steps may appear simple, but they are often quite complex in practice. The transition process typically requires one to two years for a Stage I firm; three years or more may well be required in a Stage IV firm. Some aspects of the change process (such as changes in personnel—voluntary or otherwise) can be difficult to handle. However, where the process is suitably designed and well-executed, the organization will almost always emerge from it stronger and more successful than ever.

Failure of senior management to take the necessary steps in negotiating transitions between each of the stages can have significant consequences. These range from stagnation and blocked growth to removal of the founders, as has happened at many companies. Or the company may experience bankruptcy or takeover, as happened with Osborne Computer. However, if the proper steps are taken, then organizations can experience a great deal of success. Starbucks and Microsoft are good examples of this.

Case Example of Growth from Stages I to IV: 99 Cents Only Stores

This section presents a case example of a company from its inception as a new venture through its transition to become an entrepreneurially oriented, professionally managed company. The company is 99 Cents Only Stores.

Origins of 99 Cents Only Stores

The late Dave Gold and his wife, Sherry, are a classic American entrepreneurial success story. In 1945, Dave's father, an immigrant from Russia, opened a tiny liquor store in downtown Los Angeles. In 1957, Dave's father received an offer to sell his store for $35,000, but he sold it instead to Dave and his brother-in-law for $2,000 as a down payment, with the rest being paid with no interest over a long period of time.

The Precursor to 99 Cents Only Stores

In 1961, the two entrepreneurs opened another liquor store nearby in the Grand Central Market of downtown Los Angeles. As did other, similar stores, they sold beer, wine, and hard liquor for a variety of prices.

As part of the process of doing business, they noticed that items priced at 99 cents were selling so fast that they could not keep them in stock. They decided to experiment with pricing, selling all wines priced between $0.89 and $1.29 at a fixed price of 99 cents. They advertised: “Wines of the world for 99 cents.” The experiment was a great success. They found that those items formerly sold at 89 cents sold more when priced at 99 cents! Dave Gold had some additional insights from this experiment: (1) Customers preferred the digit 9 in pricing, and (2) customers prefer fewer digits in the price.

Dave Gold had a natural genius for business. He did a number of unorthodox things that worked quite well. For example, he advertised certain products as “the world's worst.” He advertised cigarettes as “the world's worst cigarettes for 99 cents.” People bought the cigarettes to see how bad they really were! He also advertised certain wines as “the world's worst wine for 99 cents,” and people bought those, too, to see just how awful they were.

The Next Phase

In 1972, the two partners divided the business, with each receiving two liquor stores. Now Dave could go his own way. He could buy as much as he wanted and experiment however he wanted.

The Opportunistic Buyer. Dave Gold was an aggressive buyer. He was confident he could sell what he bought, and he was willing to buy in large quantities, including things he had never sold before. In 1973, Dave bought a supermarket that was going out of business at an auction. The purchase included many items that Dave had never sold before. He then purchased a general merchandise store in the Grand Central Market in Los Angeles near his liquor store. This was the beginning of a diversification of his business, and it ultimately led to the development of 99 Cents Only Stores.

Another example of Dave's willingness to buy occurred in 1976. Kimberly Clark, manufacturer of Kotex, had overproduced the product. Dave purchased six truckloads of Kotex. There was, however, one little problem: there was no place to store all of this merchandise. At the time, Dave's father owned an old garage located in Skid Row in Los Angeles. He let Dave use it as a warehouse to store the product, and there was also space for more storage of products.

Diversification. After a few months, small retailers began coming to the warehouse to purchase products. This led, in turn, to the creation of a business unit (which still exists today) called Bargain Wholesale, which sells merchandise at below-normal wholesale prices to retailers, distributors, and exporters.

The Genesis of the Concept of 99 Cents Only Stores

It has been said that success is the result of preparation meeting opportunity. One of Dave Gold's greatest strengths as an entrepreneur was his willingness to experiment and take risks. He learned from both successes and difficulties encountered. Since his original experimentation with selling wines and cigarettes for a fixed price of 99 cents, Dave had been flirting with the idea of creating a store that would sell everything for 99 cents. His belief that this would be a good idea was enhanced by an experiment that he conducted at trade shows.

It is a common practice at trade shows for exhibited items in a booth to be sold at deeply discounted prices rather than being carted back after the show is over. Dave tried an experiment. Instead of selling the products he brought to a trade show at a variety of prices, he separated his products into three tables with three price points: $1, $2, and $5. The experiment had two significant outcomes: (1) total sales exceeded sales of previous years where things were sold at a wide variety of prices, and (2) the “$1 table” sold the most. Dave was still not ready to launch his idea of a “99 Cents Only Stores” concept. The idea would, however, continue to intrigue him.

Stage I: Accidental Launch of 99 Cents Only Stores

Dave had been talking about this idea for a very long time with a number of people, including an old friend named Jimmy Wayner. One day in 1982, while driving near the airport, Dave and Jimmy spotted a store for lease. His friend said, “I am sick of you talking about your 99 cents idea. You either rent this building, or you never talk about this with me anymore!”

Dave rented the 3,000-square-foot facility and 99 Cents Only Stores was born. This first store would be the initial seed of the company that would ultimately become 99 Cents Only Stores. Such was the accidental launch of the 99 Cents Only Stores concept—the first of its kind in the United States.

Stage II: Expansion of 99 Cents Only Stores

Dave and Sherry acquired a warehouse to store merchandise and proceeded to expand the business by opening more stores. Dave and Sherry traveled to trade shows and auctions to find products, which they purchased for 50 cents per unit; they had a van or truck there so they could ship everything back to Los Angeles.

The company was aided in its development of the business by a great deal of free publicity. Because the concept was novel, the media were interested. The Herald Examiner, a Los Angeles newspaper, put the company on the front page with a story. The company also received coverage from various local channels, as well as CNN.

Dave and Sherry raised three children: Howard, Jeff, and Karen. In 1984, Dave and Sherry opened their second store. All of Dave and Sherry's children were involved in the business from an early age, and all occupied important positions in the firm.

By 1996, 99 Cents Only Stores had a total of 36 stores—all in Southern California. In May of 1996, the company did an IPO and became a public company on the NYSE, trading under the symbol NDN. One long-time observer of the company expressed the belief that a major reason Dave Gold took 99 Cents Only Stores public was to give employees a chance to participate in the value created by the growth of the company. In fact, the company launched a stock option program in which employees can participate.

Even after going public, the members of the Gold family were committed to the success of NDN. In addition, the family knew a great deal about the business from its many years of involvement. For almost a decade after the IPO, family members continued to be the driving force in the business. By 2004, the company had grown very large and more complex. It now had more than two hundred stores and was operating in four states (California, Nevada, Texas, and Arizona).

Like all companies experiencing rapid growth, NDN was beginning to experience some of the classic growing pains that will be described in Chapter 5. Management focused on dealing with the company's growing pains and preparing to take NDN to the next level of success. The company added new members to its board, added additional depth to its management team, initiated a new process of strategic planning, developed more sophisticated supply chain operations, revised and upgraded its operational systems, and put into effect a number of other initiatives designed to strengthen the company and build on its existing strong foundation. In doing so, the company applied many of the concepts and tools presented in this book.

Stage III: Transitioning to Professional Management

By 2005, under Dave Gold's leadership, 99 Cents Only Stores had grown to 225 stores and almost $1 billion in revenues. The innovative business concept pioneered by Dave Gold had also spawned a number of imitators and, in fact, had created a new business category: the $1 store concept.

After more than 50 years of involvement in the business and its precursor, Dave Gold made the decision to retire on December 31, 2004. This led to a management succession at the executive levels of the company. Dave Gold continued as chairman of the board. His son-in-law, Eric Schiffer, who holds an MBA from Harvard Business School and joined the company in 1991, became CEO. Dave's son, Jeff Gold, who has been involved in the business for many years, became president and COO and took over responsibility for day-to-day operations. Howard Gold, also involved in the business for many years, became executive vice president (EVP) for special projects. In addition, the company hired a new CFO and created the position of EVP for supply chain operations. It also recruited experienced professionals in several other areas of the company, including human resources.

Stage IV: Consolidation

Under the new leadership of Eric Schiffer and Jeff Gold, the company developed a culture statement to formalize the values that had been underlying its operation for many years.

Conclusion

The inception, growth, and transition to professional management of 99 Cents Only Stores is truly an impressive business success story. The company created its business concept and defined a new business space. The company successfully made the transition from a family-driven business to a publicly held, professionally managed enterprise.

In 2012, the company went private, in a purchase by Ares Management and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board as well as the Gold-Schiffer family in a deal valued at $1.6 billion. At the time of the buyout, the company had approximately $1.5 billion in revenues. The company still operates throughout several western states as well as its home state of California.

Summary

This chapter presents a framework to help senior managers understand and guide organizations at different stages of growth and development. It describes the first four major stages of organizational growth, from the inception of a new venture (Stage I) to the consolidation of a professionally managed organization (Stage IV). It examines the degree of emphasis that must be placed on each level of the Pyramid of Organizational Development at each stage of growth. It also examines the differences between an entrepreneurial and a professionally managed organization and describes the steps that must be taken to make a successful transition from one stage of growth to the next.

In the next chapter, we examine the remaining three stages of growth comprising the organizational life cycle: diversification, integration, and decline-revitalization.