Chapter 7

Setting Yourself Apart From Your Competitors

IN THIS CHAPTER

Demonstrating the features and benefits of your solution

Selling yourself with discriminators

Proving to customers that your solution works

In this chapter, we start to look at the actual writing of the proposal. Sure, you may have written your topical outline by now (refer to Chapter 6), and if you’re not used to writing, that may have felt like a huge task in itself. You may have also worked with your sales lead to boil your customer’s hot buttons and your solution’s key benefits into a one-sentence, memorable win theme (refer to Chapter 2). And you’ve supported this cornerstone concept with a number of supporting proposal themes that you’ll echo throughout the proposal (refer to Chapter 6 again). But really, you’ve only just started.

If the win theme is the cornerstone of your proposal, the benefits — those tangible improvements to your customer’s business that your solution brings — and the discriminators — those advantages that only you can bring to your customer’s solution — represent the framework of your proposal. They serve two main purposes:

- They make your solution meaningful to your customer. Benefits and discriminators reinforce that your solution will take away the customer’s pains that stem from its problem or need. They express the whys that persuade customers to buy. They place you and your solution inside the workings of the customer’s business, and that makes your solution real to your customer.

- They bring structural integrity to your proposal. Benefits and discriminators echo your win theme and your underlying theme statements. You use them time and again to reiterate your solution’s value and your organization’s trustworthiness. They add the needed emotional appeal to your argument, touching on matters that mean most to your customers.

And then you have the proofs. They’re the underpinning for the entire proposal. Proofs are the evidence that you can do what your win theme says you can. They’re the examples that add heft to your logic and the ring of truth to your benefits. They’re the confirmation that your solution is the best choice for your customer.

This chapter takes you through each of these three elements: features and benefits, discriminators, and proofs. After you get these key parts of your proposal down, the rest is just a matter of placing them throughout the structure of your reactive or proactive proposal outline so they’ll sell your solution from start to finish.

Presenting Features and Benefits

Integral to your proposal is an inseparable pairing. You can call this pairing feature–benefit statements. As we explain in Chapter 2, features are the physical things or services you offer to solve your customer’s problem. Benefits are what the feature makes possible in terms of improved process or performance for the customer. You can’t have one without the other, so it’s best to pair them in your proposal.

To grasp how these three aspects relate to each other and to your customers, it may be helpful to think of

- Features as the what, as in “What is it and what does it do?”

- Benefits as the so what, as in “So what does it mean to me?”

- Discriminators as the how well, as in “How do you do things that matter better than your competitors?”

Features and benefits are so critical to a persuasive proposal that we need to look into each more closely. Benefits are so important that we need to qualify them with a special test to be sure we represent them properly. And discriminators — the benefits that mean the most to your customers — deserve a section all to themselves.

Describing your proposal’s features

In a proposal, features are the vehicles for providing benefits to your customers. Features are tangible aspects of products that set them apart from your competitors’ versions. They’re the pieces of equipment that customers can watch you install or calibrate; the functions within a website that your customers can observe working on a screen; the physical aspects of a tool that your customers can handle and use themselves. For services, they’re the means by which customers communicate with you; the schedules and processes you follow to meet your customers’ needs; the rigor you apply when you solve your customers’ problems. Whether product or service, features are normally things that are measurable and demonstrable.

Providing the right amount of detail about your features

How much do customers need to hear about your features? That depends on the type of customer you’re seeking and the individual who will make the final decision to buy. Here’s a rule of thumb: The higher the managerial level of the person you’re writing to, the less about features you need to include.

Regardless of your audience, within the proposal, less is more. List only those features that are pertinent to the needs of the customer. If you deem some features as “value adds,” discuss them briefly after you list the features that respond best to your customer’s requirements.

Determining the best way to present features

- Highlight a major operational element of the feature. For example, SureGuard’s Phone App: Monitor Your Home Security.

- Link the upcoming feature to a key benefit. For example, Arm or Disarm Your System Remotely with SureGuard’s Phone App.

- Point out features that are positive discriminators. For example, Only SureGuard Feeds Live Video Feeds to Your Phone.

Check out the later sidebar “Get your headings to shout about your discriminators” for a look at the value of effective headings in more detail.

If your features are fairly simple to explain, use a bulleted list. Order the entries in matching priority to your customer’s requirements. You can also consider using a table (as an alternative to a list). Tables can be very effective for setting apart important information that also requires a little explanation. Whichever method you choose, start with the official name of the feature, followed by a brief description of what it’s for, what it does, and perhaps how it works.

Phone app: Allows you to monitor your SureGuard home security system 24/7, using a simple touch-screen interface. The app is available on all mobile phone platforms and is fully configurable for your needs. It allows you to stream videos from your home cameras and to arm and disarm your system remotely.

Clarifying benefits

Features are the what of your offer. But oddly, the whats don’t really convince customers to buy. Benefits — the so-whats — do, especially when you can enhance those benefits with your unique discriminators (something that we explore in more detail in the later section “Quantifying the value of benefits with discriminators”).

Benefits are the results that stem from applying features that solve customer problems. They describe the value that the customer can achieve from your solution to its problem. To claim a benefit, a feature of your offer must clearly allow the customer to realize the benefit — it’s a one-to-one relationship.

Phone app: If you’re stuck in traffic and need to let visiting relatives into your house, you can disarm the alarm from your cellphone just before they arrive, and maintain your home’s security until they arrive.

Benefits help customers achieve their goals — goals that go beyond merely solving the problem — because they answer the question, “So what?” The example explains the practical benefit that the phone app’s feature supplies.

Benefit statements may be the hardest thing to write in a proposal. Many writers confuse them with features, or even with the new capabilities that result from using the features. Technical experts, who clearly understand the significance of features, have an especially hard time distinguishing the difference.

Consider the examples in Table 7-1 to help you make sense of the differences between features and benefits.

TABLE 7-1 The Differences Between Features and Benefits

|

Problem |

Pain |

Feature Statement |

Benefit Statement |

|

Secure sensitive information on website. |

Your customers are unwilling to purchase tickets online; they’re afraid that their credit information is at risk. |

Encrypted transactions |

Encodes your customers’ card numbers and other personal information so they can buy with confidence |

|

Attract new customers with easy-to-use web features. |

Your customers give up on transactions because they can’t find what they need. |

Reconfigured user experience with simplified navigation |

Secures transactions so your customers can easily and quickly find merchandise and order or manage tickets |

Applying the “so what?” test

When you look at the problem, pain, feature, and benefit statements side by side (refer to Table 7-1 for some examples), you see how the feature (usually written as nouns and noun phrases — for example, “encrypted transactions”) is the working element of the solution that solves the problem. You express features in terms of what they do (the what of your solution that speaks to technical evaluators). What makes features become meaningful to less technical evaluators is the benefit that combines the feature (for example, it encodes card numbers) with the business result that it enables (for example, that as a result, people can buy with confidence).

To make sure your benefits aren’t just reworded feature statements, ask yourself “so what?” after you read them. A feature statement won’t be able to answer the question, whereas a benefit statement will provide a clear answer by expressing the action that your feature performs and the results that the action achieves — which serves to address your customer’s specific problem or need.

Quantifying the value of benefits with discriminators

To test whether your benefit statements truly express benefits and not just features, you ask “so what?” about each one. But to truly convince your customers of your features’ value, you need to couple the “so what?” with another question: “How well?” — that is, “How well does your benefit satisfy the customer’s most important needs?” The answer lies in discriminators.

Well-written positive discriminators acknowledge the different roles that readers of the proposal will have and the different perspectives and motivations that each person brings to a collective decision.

Encodes customers’ card numbers and other personal information so they can buy with confidence

Imagine that your encoding scheme is world-class, with secret-service-level security. No other competitor can compare. That will resonate deeply with technical evaluators, putting your solution at the top in their minds.

For their endorsement, you can therefore embellish your benefit statement:

Encodes customers’ card numbers and other personal information with the same technology used by government security agencies so customers can buy with confidence

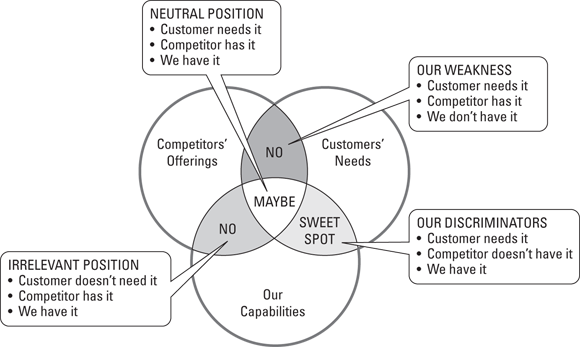

Figure 7-1 shows where your customers’ needs, your competitors’ capabilities, and your own capabilities intersect — identifying the “sweet spot.” Positive discriminators lie in the single segment where you offer something that no one else does and where that something matters to the buyer. No other set of conditions fully qualifies as a discriminator.

Source: APMP Body of Knowledge

FIGURE 7-1: Look for your discriminators at the discriminator sweet spot — the intersection of your customer’s needs and your capabilities.

Although customers base their buying decisions on benefits (both tangible, like a physical feature, and intangible, like a perceived capability), quantified benefits are more compelling than those that don’t deliver a measurable value proposition. But beware: You must also be able to prove the quantification claim. If you have no evidence that your encryption scheme doesn’t beat the competition’s hands-down, find another discriminator.

You want to quantify your benefits with discriminators whenever you can. They’re especially convincing if you can convey them graphically, but at the very least, consider adding them to as many of your benefits as possible.

Backing Up Your Claims with Proof

Evidence wins arguments. Proof points make your proposal arguments compelling to a customer. They often describe performance on similar past efforts. A proof point may consist of project data, case studies, customer quotes or testimonials, awards or recognition earned, and more.

The following sections look at some different ways to prove that your stated benefits can deliver the goods.

Using past projects to back up your claims

Customers prefer organizations that can demonstrate both relevant experience in the work that they need to have done and a track record of successful past performance. A great way to provide evidence that you can do what you say is to cite examples of how you’ve done it in the past on projects with similar goals and of comparable size, scope, magnitude, and complexity. Your examples need to illustrate your work on successful projects that you delivered on time, within budget, and to customer specifications.

What parameters of past performance should you include? That depends on your customer’s needs. In complex procurements, you may be asked to provide detailed information about a range of categories, such as the following:

- Contract name, customer name, contact name and information

- Dollar value/contract type

- When you performed the work

- Project objectives and key solution deliverables

- How the customer benefited from your work

- Scope of work performed

- Locale of work performed

- Project performance

In less complex situations, you may need to provide a customer reference, with a name and number to contact for verification. Sometimes, a mere testimonial quote from a satisfied customer can solidify your claim.

Some customers may place greater importance on past performance than others. But no matter what the setting, clear descriptions of past performance can help build confidence in your solution and your ability to perform.

Making your proof persuasive

Proof points must be persuasive by substantiating the features and benefits that meet or exceed customer objectives and requirements. Here’s an example of a persuasive proof point:

The details in this example help to persuade readers that your proofs are valid.

- We enjoy high levels of customer satisfaction. How high?

- We have low employee turnover. Compared to what?

- We offer relevant experience. In what?

Some workers will realize productivity gains.

Instead, write:

Your 28 support staff clerks will reduce their filing and follow-up time by an average of 18 percent, or 1.4 hours per day.

The second statement is much more persuasive. So don’t spare the details when you’re describing your features, benefits, and discriminators.

Making your proof tangible

Proof points must be tangible. They must provide measurable facts and figures. For example:

To demonstrate your organization’s size and strength, you can present data that shows your locations, divisions, subsidiaries, and programs/projects, preferably through graphics, charts, and tables. If you’re the prime contractor working with a partner, pull together the data that represents the combined entities (revenues, locations, employees, projects, certifications, and so on). Merely aggregating data is not effective, however. When you provide numbers, always explain to readers what they mean.

Table 7-2 provides an example to demonstrate how you can provide accurate proof points based on aggregated data.

TABLE 7-2 Aggregating Proof Points

|

Entity |

Service Locations |

Service Vehicles |

Service Technicians |

|

Our Company |

14 |

78 |

156 |

|

Partner A |

9 |

27 |

48 |

|

Partner B |

12 |

66 |

122 |

|

Total |

35 |

171 |

326 |

Our combined service personnel outnumber our competitors’ by 2 to 1. Our combined service coverage places technicians within 25 miles of your branches, and our fleet can arrive for repairs within 30 minutes.

Making your proof credible

Your proof points must be credible. They must provide verifiable information. For example:

Your discerning customer may want to verify your proof points, so make them tangible by identifying all data sources and providing specific customer references and quotes (ask for customer permission before using direct quotes).

Some potential sources for tangible proofs include

- Case studies reported by trade magazines and sources

- Citations of industry recognition of innovation or longevity

- Awards or ratings from external, unbiased third parties

- Published data that shows size or financial strength

- Comparisons to show that your solutions meet or exceed industry performance standards (which will also ghost the competition; refer to Chapter 5 for more on ghosting)

For every feature, you must have a benefit. For every benefit, you must have a feature. Otherwise, forget them — a feature that brings no benefit is worthless, as is a benefit a customer doesn’t need.

For every feature, you must have a benefit. For every benefit, you must have a feature. Otherwise, forget them — a feature that brings no benefit is worthless, as is a benefit a customer doesn’t need. Although features and benefits come as a pair in your proposal writing, you need to keep in mind that customers are sold on the benefits they receive from a seller’s solution, not the features that the seller touts. With proposals, you always need to think about the customer. Yet many businesses fail to look beyond their own selling perspective to create valid links between their features and the benefits that customers receive. A deeper understanding of your customers’ needs, your competitors’ offerings and strengths, and your own capabilities (features) and unique characteristics (your discriminators) allows you to communicate compelling, trustworthy benefits to buyers.

Although features and benefits come as a pair in your proposal writing, you need to keep in mind that customers are sold on the benefits they receive from a seller’s solution, not the features that the seller touts. With proposals, you always need to think about the customer. Yet many businesses fail to look beyond their own selling perspective to create valid links between their features and the benefits that customers receive. A deeper understanding of your customers’ needs, your competitors’ offerings and strengths, and your own capabilities (features) and unique characteristics (your discriminators) allows you to communicate compelling, trustworthy benefits to buyers. More and more managers are technically savvy. Make sure that you know your audience’s level of technical expertise and that you respond accordingly.

More and more managers are technically savvy. Make sure that you know your audience’s level of technical expertise and that you respond accordingly. Here’s an example of a feature explanation within a bulleted list (the what):

Here’s an example of a feature explanation within a bulleted list (the what):