Chapter 3

Building Customer Relationships

IN THIS CHAPTER

Tailoring your proposals to your customers

Engaging with your customers

Managing the relationship with your customers

Customers, no matter who or where they are, tend to behave in predictable ways: They choose to work with other people and companies that they know, like, and trust. In certain markets, like in governments, your customers have to follow closely monitored procurement regulations, evaluate you against specific formal criteria, and even publish the results for the world to see. But despite these constraints, if they know, like, and trust you, they’ll figure out a way to pick you over other businesses. Conversely, if they don’t know, like, and trust you, they’ll figure out a way not to pick you.

As you begin the process of writing your proposal, keep this mantra firmly in mind: Your proposal is not about you — it’s about your customers. It looks like them. It sounds like them. It follows their line of thinking. It reflects the relationship you have with them. Therefore, you need to get to know your customers long before you deliver your proposals, and you continue to develop your relationship with them long after they’ve read the last sentences or crunched the last numbers.

In this chapter, we help you establish and enhance relationships with your customers, use those relationships to create more persuasive and effective proposals, and use those proposals to continually improve relationships with your customers so they’ll know, like, and trust you better than they do your competition.

Getting to Know Your Customers

Quick — off the top of your head — what’s the most important part of a proposal or Request for Proposal (RFP) response? The executive summary? You may say that because the broadest audience of evaluators and decision makers will almost certainly read it. How about the pricing section? You’d be right to suspect that some readers will bypass the rest of your proposal for a close look at the bottom line (don’t you hate it when they do that?).

And guess what — both viewpoints are right. Both sections are critical for your proposal’s success but not necessarily for the reasons you may think. As important as your solution and numbers are, they’re less important than how your customers perceive you and your company. If you’re going to propose anything beyond a simple commodity, your customers’ decision-making process may come down to how well they like doing business with you and how much they trust you.

The following sections explore how you win over your customers — how you craft your proposal to show that you understand their needs and how their business works. We also introduce some useful questions that you can ask to tailor your approach to your customers and to help you discover their deeper business needs.

Getting real: Your customer’s business is your business

Every proposal writer has to find out as much as possible about the customer — its business, decision makers, and all the evaluators and influencers who will assess your proposal. You can do this by asking questions. If you personally know the customer through sales visits, you can get answers directly. If you don’t get to meet with the customer, you have to get someone else to ask for you and then give you the answers.

- Set up the sales meeting (ask for the date)

- Figure out how the customer’s business operates (ask what your date likes to do)

- Identify the customer’s business goals (ask where your date wants to go)

- Uncover the customer’s problems and needs (ask what your date dislikes)

- Determine when changes are needed (ask when your date needs to be back home)

- Offer to develop a proposal (ask for a second date)

You need to have a good relationship with someone before you decide to propose marriage — and before that someone may consider accepting your proposal. Business is similar. An unsolicited proposal to a company you don’t know well will fall on deaf ears almost all of the time.

You may be thinking, “So you’re saying there’s a chance …” — yes, but it’s a slim chance. Your unsolicited proposal has about as much a chance as someone walking up to a complete stranger at a bar and proposing marriage. The result: at best, an incredulous laugh, and at worst, a slap in the face. And that’s about what you can expect from submitting a proposal that a customer hasn’t asked for or isn’t expecting.

Starting right: Asking opening questions

You’ve asked for the sales meeting. How do you prepare for that meeting with the end game in mind? The process is twofold, even if you’re both the customer contact and the writer of the proposal.

Table 3-1 contains two sets of questions. In the left column are ten starter questions that you (or your sales rep) need to ask your customer to start the conversation, move the discussion to a meaningful dialogue about the customer’s needs and your abilities, and set up an opportunity to develop a relationship and ultimately propose a solution and close a sale.

TABLE 3-1 Asking Your Customer Some Initial Questions

|

What the Salesperson Asks the Customer |

What You Ask the Salesperson |

|

What markets do you serve or want to serve? |

Are our services available in this market? |

|

What prior solutions can we reference? | |

|

What are you trying to achieve, short term? |

Do our solutions match the customer’s immediate goals? |

|

What are your long-term goals? |

Do our strategic goals align with those of the customer? |

|

How do you operate your business today? |

What insights can we bring from working with other customers in this business? |

|

Do we have resources that understand this customer’s operations? | |

|

What operations problems concern you? |

Can we describe these problems in the customer’s language? |

|

Can we prioritize these problems for the customer? | |

|

When and how do these problems occur? |

Can we raise FUD from these issues? (FUD is proposal-writer shorthand for fear, uncertainty, and doubt. These are the kinds of pain points that can turn problems and needs into hot buttons — emotional reasons to buy.) |

|

Do we have experience solving these kinds of problems? | |

|

What are the financial repercussions? | |

|

What have you done to remedy the situation? |

Can we ghost this approach? (See Chapter 5.) How can we improve upon this remedy? |

|

Who do you do business with today? |

What do we know about this competitor? |

|

Can we ghost this competitor? (See Chapter 5.) | |

|

Is your current provider solving problems as quickly and effectively as you would like? |

Do our assets indicate we can respond faster than the incumbent? If so, how specifically and to what degree can we improve on the incumbent’s performance? |

|

When can we meet again? |

How fast can we build a preliminary assessment of the prospect’s situation and follow up with a proposal? |

* Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats

Getting answers to the questions in the left-hand column prompts you to assess the potential of having a relationship with this customer. The right-hand column then lists the questions that your proposal writer (or the proposal writer in you) will need answers for if you’re going to take the relationship to the next level.

Digging deeper: Understanding the needs of your readers

While a salesperson is normally concerned with understanding the customer’s business needs, a proposal writer needs to know this information, too, plus some additional information to help build a proposal that meets the individual communication needs of all readers within the customer’s organization. To get this extra detail, you need to dig a little deeper into the personalities and preferences of the proposal decision makers and evaluators. (Yeah, more questions.)

The process for writing any sales, financial, marketing, or technical document (a proposal is a unique blend of all of these) begins with a comprehensive analysis of your readers. Knowing your readers (rarely just one, mostly many) affects what you say and how you say it. If you’re a salesperson, you have the greatest insight into your readers — hopefully you’ve spoken to the decision maker and any influencers multiple times. If you’re a proposal writer who doesn’t get out much, you have to get that information from your salesperson. If you’re sending your proposal out cold, you’ll have to research your customer through third-party sources to find out all you can about who’ll be reading your proposal.

Regardless of your situation, the questions in Table 3-2 can help you to discover all you can about the person or people who’ll read your proposal, evaluate your offer, and decide whether to accept or reject it.

TABLE 3-2 Reader Analysis Questionnaire

|

Question |

Comments |

Strategy |

|

Who is your decision maker? |

This is the person or persons most likely to have the final say about your offer. |

Use the words and anecdotes you heard this audience use to describe the current needs and the pain suffered. Address the kinds of problems that keep leaders awake at night (such as market share and top-line revenues). |

|

Who are the influencers? |

These are the people who help the decision maker make the final decision — the technical staff, finance team, or selection committee. |

Think about all the voices that weigh in on the decision and design content elements to address their concerns. Include features and specifications for the technical staff and ROI (return on investment) for the finance team. |

|

What is each reader’s level of education? |

This determines the balance of text and visual material you supply. For multiple audiences, make sure your text and visual elements can stand on their own. |

Opt for more text the higher a reader’s education and technical knowledge; opt for more visuals the lower a reader’s education and the higher the reader’s level in the company (time issue). |

|

What is each reader’s level of technical expertise? |

This tells you what technical terms you can use and whether you’ll need to explain concepts. |

If your primary audience is non-technical but has technical advisors, write your body text to the non-technical reader and supply technical details in a sidebar or appendix. |

|

What is each reader’s professional experience? |

This tells you how much background material and detail you need to supply. |

Provide a brief summary of the need and move directly to the recommendation; provide needs, pain points, features, and benefits within your recommendation. |

|

What is each reader’s familiarity with the subject? |

This tells you whether you’ll need to explain the reasons for the proposal. |

If your reader is your decision maker and familiar with the subject, quickly remind him or her of the need that prompts the proposal and outline your solution and costs. If your reader is less familiar, fully explain your understanding of the situation and review alternatives before presenting your solution. |

|

What are each reader’s expectations? |

This helps you anticipate resistance by one or more readers up the chain of command. |

This is where you can use a technique or argument to address any issues you know your advocates will expect and your adversaries may throw at you. You can place these under a separate heading in your current situation/problem section. |

|

How enthusiastic is each reader about the project? |

This determines the priority your readers will place on reading your proposal. |

The less enthusiastic your reader, the greater the need to create a good executive summary that spells out current and future pains and the costs of not acting. You need vivid pain statements to capture your reader’s attention. |

|

What is each reader’s urgency for finding a solution? |

This relates directly to costs — the losses mounting through inactivity versus the cost of fixing the problem. |

Highlight costs in the transmittal letter and the executive summary. Provide graphic proofs of payback period, ROI, and bottom line improvements, if possible. |

|

What is each reader’s reading environment? |

This determines how you package and lay out your proposal to simplify evaluation. |

Include a compliance matrix if not already required by an RFP. Consider a separate executive summary so decision makers can read in parallel with technical evaluators. |

|

What do your readers need to do or understand? |

This helps you facilitate faster action by your readers. |

Make any customer actions, such as implementation considerations and leasing/buying issues, clear and actionable. Make sure you highlight this content and clearly indicate who will do what. |

Table 3-2 doesn’t list all the questions you need to ask to understand your customer, but it’s a great reference that has helped fledgling and seasoned writers customize their proposals to better speak to their customers. Combined with the information your salesperson gathered from the questions in Table 3-1, these questions help you build a strong foundation for establishing a relationship that can lead to a winning proposal.

Winning customers: It’s all about them

Before you hand over the proposal, you need to understand some principles of customer relationships and how they translate into successful proposal elements. If you want your customer to know, like, and trust you, you have to master — and genuinely demonstrate — these principles in your customer interactions and especially in your written proposals.

We don’t tell you how to talk business to your customers; that’s not our job here. The next few sections do, however, help you take what you hear and say at a customer visit and turn that information into content that reinforces the relationship you build with your customer.

Make the message about them

The first principle for getting your customers to know, like, and trust you bears repeating: Your message has to be all about them, not about you. This is especially true of proposals. Many proposal writers — often at the insistence of their own organizations — create self-centered documents. They reflect the branding, colors, and public personas of their business, not their customers’ business. As a result, their proposals all look and sound the same, regardless of the customer.

Customers prefer that the proposals they receive be customized for their needs. They want to believe that each proposal they receive has never been submitted to another company because no other company is like theirs. Rightly so, they believe that no other company shares their distinctive business approach, their unparalleled products, or their unique set of problems. Think about it: If they were like other companies, why would they be in business? So this first principle surpasses all others: A proposal is a one-of-a-kind, customer-focused message.

What does this mean in practical terms? Here are three key ideas to keep in mind:

-

Place yourself in a subordinate position to your customer. Many companies emblazon their proposals with their corporate logos, colors, and imagery. They see proposals as another marketing tool for the masses, like a corporate website or a brochure on steroids. But they’re not — proposals are customized sales messages that have to persuade individual customers to pony up their hard-earned funds to buy something from you. One way to show that you care about your customer is to place your branding in a position subordinate to its branding — for instance, in the bottom-right corner of the proposal cover and in footers instead of headers on pages. Using your customer’s logo, brand colors, and imagery in superior positions sends a not-so-subtle message that it’s all about them.

If you decide to use your customer’s logo and other brand indicators, make sure you ask permission before you display this copyrighted information. Never disrespect a customer’s branding.

If you decide to use your customer’s logo and other brand indicators, make sure you ask permission before you display this copyrighted information. Never disrespect a customer’s branding. - Accurately describe your customer’s current environment. Another great way to show your customers that you care is to do your homework about their business. Start by researching industry challenges. For a medical office, that may mean patient privacy concerns or rising fraud claims. For a university, that may mean campus security or cost-control efforts. Knowing your customer’s business thoroughly is a great way to instill confidence that you’ve got its best interests at heart. And much of that knowledge is just an Internet search, an annual report, or a trade magazine article away. Your self-education in your customer’s business reaps great benefits when you get your face-to-face meeting and get the customer’s personal story about the business.

-

Go easy on the boilerplate. Boilerplate is reusable content that explains products, company histories, and even solutions in generic marketing terms. Nothing screams, “I don’t really care about you and your problems” like boilerplate that’s all about your company, your products, and generalized situations where those products can supposedly help.

True, boilerplate saves time and repetitive work, and it often contains content that’s appropriate for many different proposals. But you must always customize any boilerplate you use to fit your customer’s unique situation.

True, boilerplate saves time and repetitive work, and it often contains content that’s appropriate for many different proposals. But you must always customize any boilerplate you use to fit your customer’s unique situation. Apply this approach to any communications with your customers — whether emails, sales letters, or brochures. Keep the boilerplate text to a minimum and tailor it effectively each time.

Apply this approach to any communications with your customers — whether emails, sales letters, or brochures. Keep the boilerplate text to a minimum and tailor it effectively each time.

You can find out more about writing to meet your customers’ requirements in Chapter 10.

Echo your customer’s needs

As you talk with your customer initially, or as you debrief your company’s rep who talks with your customer, you’ll hear unique descriptions about what the customer’s business needs to improve to achieve specific outcomes. These are the cornerstones to a great customer-focused proposal. Being able to convince your customer that you understand industry issues and individual needs gets you well down the road to winning your customer’s trust.

You can show true empathy for your customers’ needs in two main ways:

- Describe the pain associated with the need. A major part of every proposal is describing the needs or problems that are prompting your proposal. As you talk about a need or problem, provide details about the pain it causes. For example, use a quote from a worker to spell out the pain caused by a tracking system, such as “I waste four hours a week checking and manually revising the automated reports.” By merely expressing the need or problem in terms of the pain it causes, you show you truly do know how it feels.

- Discuss possible approaches to ending the pain. When you say that you have the only solution to a problem, you may instill doubt rather than confidence. First off, it sounds arrogant. And remember, your goal is to make the customer like you. Take some time to acknowledge alternate solutions — state them, but then refute them. This is a classic, effective argument technique dating back to the ancient Greeks. Explain why the other solutions won’t work at all (or as well) in the customer’s environment. This tactic helps you to build trust because it shows that you’re not trying to sell a solution but rather trying to solve a problem.

Push your customer’s hot buttons

Hot buttons are the singularly important issues or groups of issues that compel customers to buy a product or service (refer to Chapter 2 for more details on hot buttons). You can tell a customer’s hot buttons because they come up repeatedly in conversations and usually relate to persistent issues or problems that inhibit the success of the business.

You derive your customer’s hot buttons from two sources:

- Motivators: What your customer is trying to achieve short term to realize a long-range vision. For example, a car dealership may be trying to streamline its inventory procedures to become the volume leader for its region.

- Issues: The things that your customer is worried about. They may stem from an existing problem or be driven by an upcoming revenue or operational opportunity. To continue with the car dealership example, imagine that updates to the inventory database haven’t occurred in real time, leading to confusion, repetitive work, and angry customers (who thought they’d found their dream car, only to discover it had been sold out from under them).

You need to streamline your inventory process and modernize your new- and used-car database before you can hope to compete for top sales in the region. Yet database latency has slowed your progress and caused nightmares, literally and figuratively. And your fears are well founded; you actually had one salesperson almost come to blows with another by selling the same car twice. Any solution must eliminate the latency and ensure that your inventory is up-to-date all the time.

Focus on benefits, not features

Want to turn off a prospective buyer? Provide an exhaustive list of your product or solution’s features. Customers care less about the discrete features of your products and more about what those features can do to solve their business problems.

Table 3-3 shows the differences between a couple of products, a key feature of each, and their respective benefits. One example’s pretty commonplace, while the other is more high-tech.

TABLE 3-3 Product Features versus Product Feature Benefits

|

Product |

Feature |

Feature’s Benefit |

|

Alarm clock |

Automatic time setting |

Adjusts from standard to daylight savings time so you don’t have to manually reset it. |

|

Fiber network |

Quick turn-up interval |

You’re back in business 60 percent faster than if you stay with your current provider. |

We go into greater depth about the relationship among needs, features, and benefits in Chapter 9, but the examples in Table 3-3 help to show you the big differences between features and benefits. In the meantime, just hang on to this concept: Features do things, while benefits are the things of value that result.

Differentiate your offer from all others

What makes your company or your offer different, and better, than your competitors’ offering? Consider the following questions:

- Is it your world-class product line?

- Is it your form-fits-function design?

- Is it your unmatched customer support?

Although these three examples can be effective key discriminators if you back them up with proof, the most effective key discriminators have more to do with the way you behave than what your products do. For instance, how quickly do you respond to requests for information? Do you deliver on time every time? Can your customer trust that you’ll always stand behind your product because you have every time there’s been the slightest glitch?

Think about how your customers will feel if you tout “unmatched support” as a key discriminator, yet you take two days to call them back, deflect blame for any problems, and hedge when answering a question about the contract. You’re not walking the walk.

If you listen to your customers’ concerns, repeat those concerns so they know that you get it, and work hard to solve their problems based on what you’ve heard, they’ll see how you behave and grow to trust that you’ll continue to deliver on your promises, no matter what the issue.

Here are some examples of how this approach may work for you in a proposal:

- Your key discriminator is unmatched customer support. Tell a story in your executive summary about a similar situation when you and your company went far beyond the terms of a contract to ensure customer satisfaction. Add repeat references to that story in your implementation plan or statement of work. Tack a reference to your story in the pricing section of your proposal to reinforce ongoing value.

- Your key discriminator is your dedicated account team. Create a list that covers each team member and provide complete and up-to-date contact information to close out your proposal. Identify the chain of command within the account team, with contact information for all escalations.

Use discriminators the right way

In any competitive situation, you try to set yourself apart from your competition in ways that are truly meaningful to your customer. In the earlier section “Focus on benefits, not features,” you discover the power of benefits over features. Now, think of a positive discriminator as a benefit that only you can rightfully claim.

In your proposals, you need to echo your discriminators in every interaction, and these discriminators should be significant enough that your customer can use them alone as a justification for selecting your solution over all others. So if features are the what, and benefits are the so-what, your positive discriminators are the why us.

The discriminator sweet spot is where your customer’s needs, your competitors’ capabilities, and your own capabilities intersect. It’s the perfect combination of factors or qualities to achieve a goal. An example would be a customer needing a one-hour response time for repairs: You offer that and your competitors don’t. Chapter 7 looks at positive discriminators and the sweet spot in more detail.

Discriminators lie in the single segment where you offer something that no one else does, and that something matters to the buyer. No other set of conditions fully qualifies as a discriminator. However, you can convert a feature that both you and a competitor have to a discriminator by offering a benefit around it that’s unique to your business.

Consider the example of the fiber network turn-up feature in Table 3-3. The benefit read: “You’re back in business 60 percent faster than if you stay with your current provider.” You can turn that benefit into a key discriminator — if installation interval is truly an overriding concern of your customer’s and if only you can deliver the solution that quickly — by boldly declaring, “No other provider can deliver this solution as quickly because no other provider has a node on its fiber ring so near your campus.”

Handling Customer Engagement: Your Sales Process

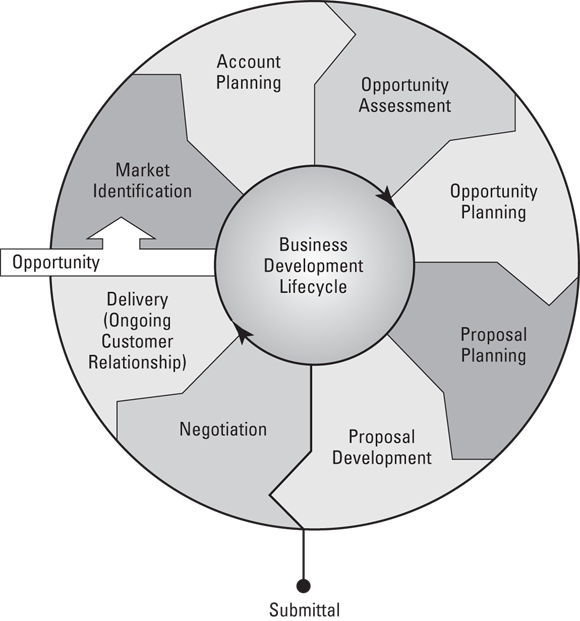

The principles discussed so far in this chapter are crucial for getting your customers to know, like, and trust you. But they don’t work unless you apply them often and consistently, preferably within a strategic, end-to-end plan for capturing, winning, and retaining business. Some professionals refer to this as the business development lifecycle. That’s a fancy name for sales process. Good proposal writers prefer simplicity; go with the simple term.

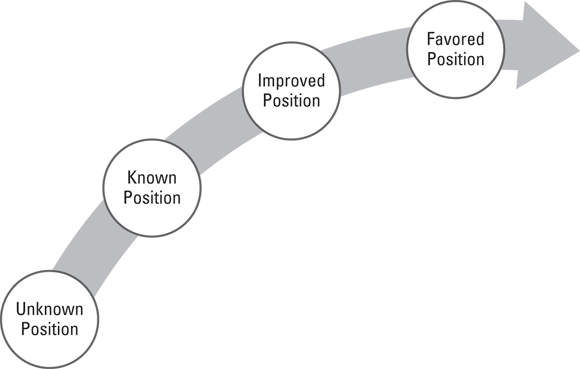

Before diving in, take a look at Figure 3-1.

Source: APMP Body of Knowledge

FIGURE 3-1: Increasing the win rate by positioning you and your company early.

Don’t let the formal language throw you off. A formal sales process is just a systematic approach for handling customer engagement from start to finish. It works whether your customer is the largest of corporations with offices around the globe or a small retail shop around the corner. You just have to tailor your sales process to fit your opportunity.

Figure 3-2 shows the eight stages of the sales process. As with Figure 3-1, don’t let this chart overwhelm you. As in all proposal-related matters, you have to scale sales processes like this through your personal filter. Not all these stages apply in every situation, so look at them in relation to a real proposal opportunity so you can assess what’s right for you in any given situation. Discipline at each of these stages improves win rates and leads to repeatable processes that help you win again and again.

Source: APMP Body of Knowledge

FIGURE 3-2: The eight-stage sales process.

The following sections take a look at each of the eight stages in more detail.

Stage 1: Finding the right market

The sales process starts before a proposal is even a glint in your eye. To have a successful business, you must decide on the markets you intend to pursue and penetrate. Doing the upfront work during this stage helps you to ensure that you spend marketing dollars and resources on the most profitable business targets.

Still, what you learn about your markets in this phase is very important to the success of your proposals. Insights into the way the market works and its key players drive bid/no-bid decisions on RFPs, and the industry issues you uncover can help flesh out your descriptions of current situations.

Stage 2: Planning a common approach for your accounts

An account can be a prospective customer, an existing customer, an entire organization, or a single buying unit within a large company. Account planning is an ongoing activity across the sales process, requiring adjustments as opportunities progress through the sales pipeline or as new opportunities arise. This stage includes marketing activities that position you in the market and with specific target customers.

- History

- Buying patterns and budget cycles

- Executives, decision makers, and influencers

- Strategies for penetrating or growing a particular customer

Stage 3: Identifying and qualifying your opportunities

This is the stage where you or your leadership makes a key, proposal-related decision: the preliminary bid/no-bid verdict on a specific opportunity. This decision is heavily influenced by decisions made during the two prior stages, because strategic planning and market positioning (and segmentation) can often dictate how you identify opportunities and put them into the sales pipeline. Your situation will be unique to your company’s approach and any systems or software that you use.

Qualifying your opportunities — that is, determining whether opportunities have a good chance of paying off — is a key stage for improving the win rate of your proposals. If you fail to adequately qualify your opportunities, you’re likely to overspend on your marketing and sales budgets and pursue too many opportunities that you have a low probability of winning. This dilutes your response resources: Desperate companies divert resources from more winnable deals and from delivery of projects that may lead to renewals. A good way to avoid this scenario is to ask a few strategic questions about a potential opportunity:

- Who is the incumbent, and how has it performed?

- Who are the known competitors, and may others be behind the scenes?

- Can you win and still make money?

- Do you need to team up with another organization?

- Will bidding for this opportunity better position you for future opportunities?

- Does this opportunity fit within your strategic plan and vision?

Assessing your competitors’ strengths and weaknesses as they relate to an opportunity is critical during this stage. You discover more about assessing your competition in Chapter 5.

Stage 4: Planning for every opportunity

Opportunity planning — that is, the process of preparing a plan specific to an opportunity and identifying actions and strategies to position your company to be the customer’s preferred provider — starts early in the lifecycle and continues through proposal submission. This planning process involves working closely with customers to understand their needs and issues. Its output is an opportunity strategy, which will feed into your proposal plan.

You can remember the key components of opportunity planning by the mnemonic “the 4Cs and P”:

- Customers: Continue to work with your customers so you know and understand their situation, needs, hot buttons, issues, and biases.

- Competition: Thoroughly analyze your competitors — especially the incumbent. Are you at a competitive advantage or disadvantage? Might the customer decide to do nothing, spend money on other things, or do the work in-house?

- Cost: Analyze the opportunity and decide on the price that will win. As you gain more information, adjust the price as needed.

- Contemplation: Take a hard look at how your customer will perceive your solution, how you’ve done on similar projects in the past, how the opportunity will affect your reputation if you lose, and the risks you’re willing to take to win.

- Portfolio: Look at all your opportunities and treat each one like an investment. Prioritize them according to the resources that each opportunity will require and how the ROI of each one compares with the probability that you’ll win it.

Stage 5: Developing your proposal plan

Inserting your proposal planning process into your company’s sales process saves your company time, resources, and money. It also saves you time in the final stages of proposal preparation (not to mention aggravation, headaches, heartburn, and maybe even your sanity!). There’s a reason the proposal writer’s standard dinner is cold pizza (and sometimes breakfast, too).

- Move data from the opportunity plan to the proposal plan (or to proposal planning tools, if you have them).

- Draft a proposal strategy based on your opportunity strategy. A proposal strategy states your company’s stance on the opportunity and how it plans to make each point in its proposal. Document the strategy by drafting an executive summary.

- Refine your solution and the price-to-win from Stage 4 (refer to the preceding section).

- Engage the right resources for the proposal team and secure executive support.

-

Host a proposal kickoff meeting to share your plan with the proposal team.

The kickoff meeting is a good time to review, validate, and suggest improvements to the proposal strategy. While you have all the experts together, have them review the technical, management, and pricing solution against the customer’s needs and requirements. This is also a good time to check how it aligns with your opportunity strategy and to appraise your competitive focus. We work you through a kickoff meeting in Chapter 6.

Stage 6: Writing your proposal

It’s your turn to shine. At some point, the opportunity will become an active proposal project, either reactive or proactive (refer to Chapter 2). The planning documents you prepared in Stage 5 (refer to the preceding section) now become working proposal development documents. During this stage, the strategy and solution should be set in concrete. Everyone needs to be on board. The proposal schedule should be untouchable.

Luckily, you have at your disposal a variety of tools and techniques to keep things on track. During this stage, you implement compliance matrixes (see Chapter 4), response assignment checklists (see Chapter 8), and reviews to ensure that your contributors are meeting the proposal requirements. You use communication tools to validate progress, troubleshoot proposal content, and address concerns. You invoke short check-in calls or meetings to monitor progress and to ensure that you meet your schedule’s milestones.

Then you set up reviews, and, depending on your situation, you can go as light (a substantive review followed by a proofreading) or as heavy (with multistaged reviews and executive sign-offs) as your proposal requires. See Chapter 6 for details on how to manage reviews of all types and when to schedule them.

You may think that when the proposal is published and submitted, you’re done. Ha! Gotcha! A proposal writer is never done (at least it seems that way).

Stage 7: Negotiating and closing the deal

Submitting a proposal doesn’t signal the end of the sales process. During this stage, business decisions become intense and more real. We know that you think your proposal was perfect, but now it’s time for your customers to ask their questions, such as the following:

- What did you mean by that?

- Is that the best price you can offer?

- Where is the part about warranties?

These questions can go on and on. You may have to modify your proposal to answer them all. You may have to help prepare final revisions, follow-up presentations, or any further documents the customer needs to decide on a provider.

During this stage, your company needs to refine its opportunity plan information and keep to a simple strategy by

- Responding fully to customer questions and concerns

- Reinforcing the customer’s trust in your solution and organization

- Optimizing the deal to the benefit of bidder and customer

Stage 8: Sustaining the relationship

Effective sales processes continue after your solution has been sold and delivered. Winning the contract is an opportunity to prove your value and position your organization for subsequent opportunities. This stage is so important that it deserves its own section (which we provide next).

Managing Customer Relationships

After you’ve archived your winning proposal, documented and discussed the lessons learned, and reaped whatever reusable knowledge you can from the engagement, it’s time for the proposal writer to move on to the next proposal. If you’re the salesperson or the sole proprietor, now comes the task of managing the customer for life (you can hope it lasts that long). This is the daily responsibility of the main customer contact. And this responsibility is where the real work begins.

You won your customer over with your charm, but you need to keep listening, meeting its needs and solving its problems (if possible, it helps to anticipate those needs and problems too). You need to stay in frequent contact. And when you do get in touch, you’d better COMMUNICATE effectively (all caps intended).

This last point reminds us of Edmond Rostand’s play Cyrano de Bergerac. In the early stages, your proposal writer was your Cyrano — he wrote your proposals to the object of your desire (your prospective customer). Cyrano not only helped Christian win Roxane’s favor, but he also continued to write letters to help him keep her. Is there something similar your Cyrano can do after helping you to secure your new customer?

As it was with Cyrano, your proposal writer’s initial work is just the beginning of a comprehensive communication plan. Although executing effectively on a contract is the best way to position yourself for future business with a customer, managing the customer relationship is all about ongoing communication with the customer. That means regular visits to the customer, product demonstrations and upgrades, social marketing campaigns, and participation in relevant industry and trade events. Communicating these actions is something your proposal writer can do better than anyone else, mainly because of the work he’s already done on the proposal.

- Create conceptual proposals for setting the stage for future proposals that relate to a recent winning proposal.

- Write internal communications for your contact to sell ideas within the customer organization.

- Establish customer-focused content for private extranet sites and social media messaging.

- Produce executive-level communiqués that provide status on in-progress projects and forecast future needs that can result in more winning proposals.

These activities, to name just a few possibilities, demonstrate an ongoing interest in your customer’s business and success and help to position you and your organization for future opportunities. And they’re all things that a proposal writer can help you achieve.

As a proposal writer, you may or may not be responsible for the customer relationship, but you are responsible for how that relationship is represented in the proposal.

As a proposal writer, you may or may not be responsible for the customer relationship, but you are responsible for how that relationship is represented in the proposal.