Chapter 2

Defining Your Customers

IN THIS CHAPTER

Targeting and reaching prospective customers

Examining your product line

Understanding the reasons why people buy products

Recognizing the importance of value

Extending and diversifying your product line

Every marketer mulls the same questions: Who are my customers? How did they hear about me? Why do they buy from me? How can I reach more people like them?

Successful businesses use the answers to these questions to influence every product-design, pricing, distribution, and communication decision they make. This chapter focuses on the only boss that really matters in business: the person with an interest in your product or service and an open billfold. Whether your business is starting up, running at full pace, or in need of a turnaround, you can use the information in this chapter to get in tune with the customers who will make or break your bottom line.

- If your business is going great guns, use this chapter to create a profile of your best customers so that you can attract more just like them.

- If your business feels busy but your sales and profits are weak, this chapter can help you differentiate between the customers who are costing you time and money and the ones who are making you money — so you can direct your marketing efforts at the moneymakers.

- If your sales have hit a frustrating plateau — or worse, if they’re sliding downhill — you need to get and keep more customers, period. That means knowing everything you can about who is buying products or services like the ones you’re selling and what it will take to make those people buy from you.

The best products aren’t sold — they’re bought. You never hear a customer say he bought a lemon at the used car lot. Nope, someone sold him that lemon — but hopefully not you or your business. If you’re a good marketer, you aren’t selling anyone anything. Instead, you’re helping customers select the right products to solve their problems, address their needs, or fulfill their desires. You’re helping them buy.

As a result, you can devote the bulk of your marketing efforts to the steps that take place long before and after money changes hands. These efforts involve targeting customers, designing the right product line, communicating your offerings in terms that address customers’ wants and needs, and interacting after the sale in a way that builds loyalty and repeat business. This chapter spotlights everything you need to know about your products and the reasons your customers want to buy those products from you.

Anatomy of a Customer: Knowing Who Your Customers Are

Understanding who’s who among your clientele is called market segmentation — the process of breaking down your customers into segments that share distinct similarities.

Here are some common market segmentation terms and what they mean:

- Geographics: Segmenting customers by their physical locations to determine the regions, counties, states, countries, zip codes, and census tracts where current and therefore likely prospective customers live.

- Demographics: Segmenting customers into groups based on factors such as age, sex, race, religion, education, marital status, income, and household size.

- Psychographics: Segmenting customers by lifestyle characteristics, behavioral and purchasing patterns, beliefs, values, and attitudes about themselves, their families, and society.

Geodemographics: A combination of geographics, demographics, and psychographics. Geodemographics, also called cluster marketing or lifestyle marketing, is based on the age-old idea that birds of a feather flock together — that people who live in the same area tend to have similar backgrounds and consuming patterns. Geodemographics helps you target your marketing efforts by pinpointing neighborhoods or geographic areas where residents share the age, income, lifestyle characteristics, and buying patterns of your prospective customers.

If you want to search deeper with these segmentations, check out Google Keyword Planner (

If you want to search deeper with these segmentations, check out Google Keyword Planner (https://adwords.google.com/KeywordPlanner) and Facebook Ads (www.facebook.com/business/ads-guide).

These sections examine these market segmentation terms in plain English so you have a better idea who your customers are and can identify them.

Collecting customer information

People with the profile of your current customers are apt to become customers as well. That’s why target marketing starts with customer knowledge. Small businesses fall into two groups: those with customer databases and those that serve customers whose names and addresses they never capture. A medical clinic or auto repair shop falls into the first group. A sandwich shop or convenience store likely falls into the second group, although even those who don’t automatically collect customer names and information can use loyalty programs or contests to collect valuable customer data.

The more you know about current customers, the better prepared you are to target and reach more people just like them. Start by doing some research.

Do-it-yourself fact-finding

You can get a good start on conducting customer research without ever walking out the front door of your business. Start by focusing on information you can collect through customer communications and contacts:

- Collect addresses from shipping labels and invoices in order to group customers by location and purchase type.

Monitor the origin of incoming phone calls. When prospects call your business, find out where they’re from and how they found you.

Keep questions conversational and brief. Remember that customers are calling to receive information, not to become research subjects.

Keep questions conversational and brief. Remember that customers are calling to receive information, not to become research subjects. - Use the caller identification feature on your phone to collect the incoming phone number prefix and area code, which can enable you to track the geographic origin of customer calls.

- Your phone service provider may be able to furnish lists of incoming call area codes or dialing prefixes for your reference.

- Track responses to ads and direct mailers. Include a call to action that inspires a reaction. When prospects respond, collect their addresses and other information to build not just a database but also an inquiry profile.

Study web reports to find out more about visitors to your website. Work with the firm that hosts and manages your site to discuss available reports and how to mine the information you collect. Also, enter your web address into Google Analytics (

www.google.com/analytics) to access data about site visitors, including their geographic origin, language, and other facts. Be aware, though, that some Internet providers hide the geographic origin of users under the label “undefined,” and others bundle all traffic, which means you may see a good many site visitors from a distant location not relevant to your business.

Be aware, though, that some Internet providers hide the geographic origin of users under the label “undefined,” and others bundle all traffic, which means you may see a good many site visitors from a distant location not relevant to your business.- Check with merchant processor company. It may have data about past transactions about customers that you can use.

Beyond studying telltale signs for the geographic origins of your business, put your small business advantage to use and actually talk with your customers, using these approaches:

Survey your customers. Use online survey services available through sites such as

www.surveymonkey.com, which allow you to choose from a range of templates and collect responses from up to ten questions from 100 people for free. Or you can create and email a survey to customers on your own or use contest forms to collect information.If your business attracts foot traffic, consider surveying customers in person. Whether you survey all customers or limit your effort to every nth customer (every tenth one, for example), keep the question period short, keep track of responses, and time interviews so that your findings reflect responses from customers during various days and weeks.

When surveying customers, keep these cautions in mind:

When surveying customers, keep these cautions in mind: - Establish and share your company’s privacy policy to assure customers that you respect and protect the information you collect.

- If you collect information online, visit the website of the Online Privacy Alliance (

http://privacyalliance.org) and click “For Businesses” for policy guidelines. - If you question customers in person, don’t risk treating long-standing customers like strangers to your business. Instead of asking, “Is this your first visit?” try to get at the answer indirectly, asking questions such as, “Have you been here since we moved the reception area?” or, “Have you stayed with us since we started our wine reception?” Savvy restaurateurs don’t have to ask at all. They know that if a customer asks for directions to the restroom, that person is likely a first-time patron. On the other hand, a waiter who overhears a customer recommending a certain menu item to a tablemate can make a safe guess that the patron is a repeat guest.

- Realize that informal studies aren’t statistically valid, but they provide interesting insights that help you better understand at least an informally assembled cross section of your clientele.

One other caution: Many retailers request zip codes before processing credit card transactions, both to aid in fraud prevention and to obtain customer data. In 2011, the California Supreme Court ruled such requests illegal. Know the rules in your state before posing the question.

One other caution: Many retailers request zip codes before processing credit card transactions, both to aid in fraud prevention and to obtain customer data. In 2011, the California Supreme Court ruled such requests illegal. Know the rules in your state before posing the question.

Observe your customers. Without asking a single question, you can find out a lot from observing customer behavior. What kinds of cars do your customers drive? How long do they spend during each visit to your business? Do they arrive by themselves or with others? Do those who arrive alone account for more sales or fewer sales than those who arrive accompanied by others? Where do they pause or stop in your business?

If your website has Google Analytics installed, you can use the “flow chart” feature to see how visitors flow through your website or web store.

If your website has Google Analytics installed, you can use the “flow chart” feature to see how visitors flow through your website or web store.Your observations help you define your customer profile while also leading to product decisions, as shown in these examples:

A small theme park may find that most visitors stay for two hours and 15 minutes, which is long enough to want something to eat or drink. This can lead to the decision to open a café or restaurant.

A small theme park may find that most visitors stay for two hours and 15 minutes, which is long enough to want something to eat or drink. This can lead to the decision to open a café or restaurant.- A retailer may realize that women who shop with other women spend more time and money, which may lead to a promotion that offers lunch for two after shopping on certain days of the week.

- A motel may decide to post a restaurant display at a hallway entry where guests frequently pause.

Calling in the pros

Doing it yourself doesn’t mean doing it all on your own. As you’re conducting customer research, here are places where an investment in professional advice pays off:

- Questionnaires: Figure out what you want to discover and create a list of questions. Then consider asking a trained market researcher to review your question wording, sequence, and format. After your questions are set, you can distribute the survey on your own or with professional help. Either way, have someone with design expertise prepare a questionnaire that makes a good visual impression on your business’s behalf. Include a letter or introductory paragraph explaining why you’re conducting research and how you’ll protect the privacy of answers.

- Phone or in-person surveys: Professional researchers pose questions that don’t skew the results. Asking the questions yourself easily lets your biases, preconceptions, and business pressures leak through and sway responses. Plus, customers are more apt to be candid with third parties. (If you need proof, think of all the things people are willing to say behind someone’s back that they’d never say to the person’s face. The same principle applies in customer research.)

- Online surveys: Professional online survey tools are free unless you want to reach very large survey groups, in which case reasonably priced packages are available. If only a portion of your clientele is active online, be sure to accompany online surveys with off-line surveys in order to capture the opinions of those who don’t use the Internet.

- Focus groups: If you’re assembling a group of favorite clients to talk casually about a new product idea, you’re fine to go it alone. But to get opinions from outsiders or insight into sensitive topics such as customer service or pricing, use a professional facilitator who is experienced in managing group dynamics so that a single dominant participant doesn’t steer the group outcome.

To obtain outside assistance, contact research firms, advertising agencies, marketing firms, and public-relations companies. Explain what you want to accomplish and ask whether the company can do the research for you or direct you toward the right resources.

Geographics: Locating your market areas

Not all businesses are geographically constrained. Most Internet businesses aren’t; most restaurants are. If geography matters to your business, though, it’s an essential ingredient in arriving at your customer profile.

To target your market geographically, you need to ask, “Where am I most likely to find potential customers, and where am I most apt to inspire enough sales to offset my marketing investment?” To help you answer these questions, here’s some advice:

- Start with the addresses of your existing customers. Wherever you have a concentration of customers, you likely have a concentration of potential customers. Unless you already have sky-high market share, those are the areas where you should direct your advertising efforts.

- Search for trends. Google Trends (

www.google.com/trends/explore) identifies search trends within a geographic area. - Follow your inquiries. Inquiries are customers waiting to happen. They are consumers whose interest you’ve aroused and whose radar screens you’ve managed to transit. Your first objective should be to convert inquiry interest into buying action. Further, by finding out where inquiries are coming from, you may discover new geographic areas to target with future marketing efforts.

- Locate new customer prospects in your local market area. Identify people who match the profile of your current customers but who don’t yet buy from you. By discovering where these prospects live, you also discover areas for potential market expansion.

- Contact media outlets that serve your business sector. Ask for information regarding geographic areas with a concentration of people who fit your customer profile. Advertising representatives are often willing to share information as a way to convince you of their ability to carry your marketing message to the right prospects.

- Contact your industry association. Inquire about industry market analyses that detail geographic areas with concentrated interest in your offerings. If you can export your offering beyond your regional marketplace, you may discover national or international market opportunities that you otherwise wouldn’t have considered.

Visit your library reference desk. Study the SRDS Lifestyle Market Analyst, a rich source of market-by-market demographic and lifestyle information, and the CACI Sourcebook of ZIP Code Demographics, which details the population profiles of 150 U.S. zip codes and county areas. Through these resources, you can find and target areas that have a concentration of residents with lifestyle interests that match up with your target customer profile. Other good resources, often available at your public library, include the Merchant Nexus Database, D&B’s Million Dollar Database, Info USA, and Reference USA.

Visit your library reference desk. Study the SRDS Lifestyle Market Analyst, a rich source of market-by-market demographic and lifestyle information, and the CACI Sourcebook of ZIP Code Demographics, which details the population profiles of 150 U.S. zip codes and county areas. Through these resources, you can find and target areas that have a concentration of residents with lifestyle interests that match up with your target customer profile. Other good resources, often available at your public library, include the Merchant Nexus Database, D&B’s Million Dollar Database, Info USA, and Reference USA.

Each time you discover a geographic area with easy access to your business and with a concentration of residents who fit your buyer profile, add the region to your list of prospective geographic target markets.

Demographics: Collecting customer data

After you determine where your customers are, the next step is to define who they are so that you can target your marketing decisions directly toward people who fit your customer profile.

Trying to market to everyone is a budget-breaking proposition. Instead, narrow your customer definition by using demographic facts to zero in on exactly whom you serve by following these steps:

Use your own general impressions to define your customers in broad terms based on how you describe their age, education level, ethnicity, income, marital status, profession, sex, and household size.

Answer these questions about your customers:

- Are they mostly male or female?

- Are they mostly children, teens, young adults, early retirees, or senior citizens?

- Are they students, college grads, or PhDs?

- What do they do — are they homemakers, teachers, young professionals, or doctors?

- Are they mostly single, couples with no children at home, heads of families, grandparents, or recent empty nesters?

- How would you describe their ethnicity and the languages they speak?

- Based on your observations, how would you define their income levels?

- When are they most in need of your service? A season, a month, a day, or a time of the week?

Break your market into subgroups, perhaps categorized by the kinds of products the customers usually purchase or the time of year they typically do business with you.

A restaurant that analyzes its weekday lunchtime clientele and patrons of its dinner business may discover that the two time frames draw customers with dramatically different demographic profiles. For example, perhaps the lunchtime clientele is comprised mostly of businesspeople from the nearby area, whereas the dinner traffic is largely tourist families. This finding may lead to the development of two different and highly targeted promotions: a 5 minutes or it’s free lunch offer aimed at the nearby business community and promoted through the chamber of commerce newsletter and other low-cost, local business publications; and a Kids under 7 eat free offer aimed at tourists and promoted through hotel desk clerks and local visitor publications.

A restaurant that analyzes its weekday lunchtime clientele and patrons of its dinner business may discover that the two time frames draw customers with dramatically different demographic profiles. For example, perhaps the lunchtime clientele is comprised mostly of businesspeople from the nearby area, whereas the dinner traffic is largely tourist families. This finding may lead to the development of two different and highly targeted promotions: a 5 minutes or it’s free lunch offer aimed at the nearby business community and promoted through the chamber of commerce newsletter and other low-cost, local business publications; and a Kids under 7 eat free offer aimed at tourists and promoted through hotel desk clerks and local visitor publications.Verify your answers by asking your customers.

Incorporate questions during inquiry and sales contacts by following the advice in the “Do-it-yourself fact-finding” section, earlier in this chapter.

Psychographics: Customer buying behaviors

Knowing where and who your customers are allows you to select the right communication vehicles to carry your marketing messages. As you decide what to say and how to present your message, you also want to find out as much as you can about the attitudes, beliefs, purchasing patterns, and behaviors of your customers. This information helps you create marketing messages that interest your prospects and motivate them to buy from you.

Defining who isn’t a prospect for your product

Sometimes, the easiest way to start your customer profiling is to think about who isn’t likely to buy from your business. For example:

A manufacturer of swing sets knows that most customers aren’t young professional couples living in urban lofts. It needs to talk to families whose homes have backyards.

A manufacturer of swing sets knows that most customers aren’t young professional couples living in urban lofts. It needs to talk to families whose homes have backyards.- A landscape and nursery business knows that it won’t find many customers in downtown high-rise apartments.

- A manufacturer of architectural siding may decide that its buyer isn’t the end user — or homeowner — at all. Rather, the customer is the architect who specifies the product in the initial building design.

Identifying the purchase tendencies customers have in common

Based on your personal impressions and also on information you discover through conversations and surveys (see advice earlier in the “Calling in the pros” section), make a list of common traits shared by your best customers by answering the following questions:

- Do they buy on impulse or after careful consideration?

- Are they cost-conscious or more concerned about the quality and prestige of the purchase?

- Are they loyal shoppers who buy from you on a frequent basis or are they one-time buyers?

- Do they buy from your business exclusively or do they also patronize your competitors?

- Do they reach you through a certain channel — for example, your satellite office or your website — or do they contact you via referrals from other businesses or professionals?

- Geographic origin: Local residents, in-state visitors, out-of-state visitors, and international visitors.

- Activity interest: Golfers, skiers, campers, and business travelers/convention guests.

Determining Which Customers Buy What

Marketing is a matter of resource allocation. No budget — not even those of mega-brands like General Motors or Apple— is big enough to do it all. At some point, every marketer has to decide to aim its dollars toward the markets and products that have the best chance of delivering results and providing a good return on the marketing investment. These sections look at what you need to know about who buys what.

Viewing your sales by market segment

The best marketers aim promotions precisely at target audiences they believe have the interest and ability to purchase the featured product. Take these steps as you match segments of your market with the categories of your product line they’re most likely to want to purchase:

- Break down your sales by product categories to gain a clear picture of the types of products you sell, the sales volume each category produces, and the type of customer each attracts.

- Use your findings to determine which product categories offer the best potential growth opportunities and also to clarify which segments of your clientele are most likely to respond to marketing messages.

- Weight your marketing expenditures and develop your marketing messages and media plans to achieve your targeted sales goals through promotions that appeal to clearly defined customer segments.

After you’re clear about which segments of your customer base are most apt to purchase which products, you’ll have the information you need to develop and communicate compelling promotions and offers. You may also discover clues to new-customer development. For example, studying sales patterns may lead to the finding that certain products or services provide a good point of customer entry to your business, arming you with valuable knowledge you can use in new-customer promotions.

Table 2-1 shows how a motel might categorize its market so that it can discover the travel tendencies of customers in each geographic market area and respond with appropriate promotional offers.

Table 2-1 Market Segmentation Analysis: Mountain Valley Motel

Hometown |

Rest of Home State |

Neighboring States |

Other National/ International |

|

Total Sales |

||||

$712,000 |

$56,960 |

$462,800 |

$128,160 |

$64,080 |

8% |

65% |

18% |

9% |

|

Sales by Length of Stay |

||||

1-night stay |

$48,416 |

$83,304 |

$19,224 |

$3,204 |

2-night stay |

$2,848 |

$231,400 |

$70,488 |

$32,448 |

3–5 night stay |

none |

$101,816 |

$32,040 |

$28,428 |

6+ night stay |

$5,696 |

$46,280 |

$6,408 |

none |

Sales by Season |

||||

Summer |

$5,696 |

$277,680 |

$96,120 |

$54,468 |

Fall |

$11,962 |

$55,536 |

$12,816 |

$6,408 |

Winter |

$4,557 |

$37,024 |

$6,408 |

none |

Holiday |

$22,783 |

$23,140 |

none |

none |

Spring |

$11,962 |

$69,420 |

$12,816 |

$3,204 |

With detailed market knowledge, you can make market-sensitive decisions that lead to promotions tailored specifically to consumer patterns and demands. The following examples show how the motel featured in Table 2-1 can use its findings to make marketing decisions:

- Local market guests primarily stay for a single night and mostly during the holiday season, making them good targets for local year-end promotions. Additionally, 10 percent of local guests stay for six nights or longer, likely while undergoing household renovations or lifestyle changes. This long-stay business tends to occur during nonsummer periods when motel occupancy is low, so the motel may want to consider special offers to attract more of this low-season business.

- Half of statewide guests spend two nights per stay, although nearly a third spend three to six nights, which proves that the motel is capable of drawing statewide guests for longer stays. This information may lead to an add-a-day promotion.

- National and international guests account for approximately one-quarter of the motel’s business. Because these guests are a far-flung group, the cost of trying to reach them in their home market areas via advertising would be prohibitive. Instead, the motel managers might research how these guests found out about the motel. If they booked following advice from travel agents, tour group operators, or websites, the managers could cultivate those sources for more bookings. Or, if the guests made their decisions while driving through town, the motel may benefit from well-placed billboard ads and greater participation in travel apps and review sites that influence traveler behavior.

Conduct a similar analysis for your own business:

- How do your products break down into product lines? (See the later section, “Getting to Know Your Product: Seeing It through Your Customer’s Eyes” for more information about this important topic.)

- What kind of customer is the most prevalent buyer for each line?

Then put your knowledge to work. If one of your product lines attracts customers who are highly discerning and prestige-oriented, think twice about a strategy that relies on coupons, for example.

Matching customers with distribution channels

Distribution is the means by which you get your product to the customer. A good distribution system blends knowledge about your customer (see the first half of this chapter) with knowledge of how that person ended up with your product (that’s what distribution is about). It’s often a surprisingly roundabout route.

Based on these numbers, the museum is distributing its tickets through the following channels:

- Educators (possibly influenced by curriculum directors)

- Tour companies (possibly influenced by state or local travel bureaus)

- Lodging establishment front desks (probably influenced by hotel and motel marketing departments)

- The Internet (possibly influenced by state or local travel bureaus)

- Partner businesses (influenced by museum networking)

- The museum entrance gate (influenced by museum marketing efforts)

By allocating guest counts and revenues to each of the channels, the museum would arrive at the distribution analysis shown in Table 2-2. By studying the findings, the museum can determine which channels are most profitable and which are most likely to respond positively to increased marketing efforts.

Table 2-2 Channel Distribution Analysis

Distribution Channel |

Ticket Revenue |

Number of Guests/ Percent of Total |

Sales Revenue/ Percent of Total |

Educators |

$5.00 |

10,000/20% |

$50,000/16% |

Tour companies |

$6.00 |

5,000/10% |

$30,000/10% |

Motels/hotels |

$6.50 |

5,000/10% |

$32,500/11% |

Internet |

|||

Museum website |

$8.00 |

3,000/6% |

$24,000/8% |

Visitor bureau website |

$6.50 |

2,000/4% |

$13,000/4% |

Museum entry gate |

|||

Museum members |

$3.00 |

5,000/10% |

$15,000/5% |

Independent visitors |

$8.00 |

15,000/30% |

$120,000/39% |

Partnering businesses |

$4.00 |

5,000/10% |

$20,000/7% |

You can create your own channel analysis, providing your business with information about how customers reach your business and the levels of sales activity that each channel generates. Put your findings to work by taking these steps:

Track sales changes by distribution channel.

If one distribution channel starts declining radically, give that channel more marketing attention or enhance another channel to replace the revenue loss.

Compare percentage of sales to percentage of revenue from each channel.

Channels that deliver lower-than-average income per unit should involve a lower-than-average marketing investment or deliver some alternative benefit to your business. For example, in the case of the museum in Table 2-2, the tickets distributed through partnering businesses deliver lower-than-average revenue and likely require a substantial marketing investment. Yet they have an alternative benefit — they introduce new people to the museum and therefore cultivate membership sales, donations, and word-of-mouth support.

Communicate with the decision makers in each distribution channel.

When you know your channels, you know whom to contact with special promotional offers. For example, if school groups arrive at a museum because the museum is on an approved list at the state’s education office, that office is the decision point, and it’s where the museum would want to direct marketing efforts. If school groups arrive because art or history teachers make the choice, the museum would want to get information to those art or history teachers.

As part of your channel analysis, consider whether your business can reach and serve prospective customers through new distribution channels, whether that means introducing online sales, off-premise purchase locations, new promotional partnerships, or other means of reaching those who fit your target customer profile but who don’t currently buy from your business.

Catering to screen-connected customers

In addition to everything you find out about your customers — who they are, where they live, how they buy, and what they want — realize that one common denominator applies to all: They’re all influenced by the Internet.

Even if your customers are among the rare few who aren’t online, you can bet that their purchase decisions are affected by input from those who are.

Research shows that 89 percent of consumers find online channels trustworthy sources for product and service reviews, and an even greater percentage use online media before purchasing products, even in their local market area. Go to Book 2, Chapter 2 for information on preparing your business to connect with your customers online. It’s where they are, so it’s where your business needs to meet and interact with them.

Getting to Know Your Product: Seeing It through Your Customer’s Eyes

The first step toward stronger sales is to know everything you possibly can about the products you sell and the reasons your customers buy.

Look beyond your primary offerings to consider the full range of solutions your business provides. Likely you’ll discover your offerings are more diverse than you first realize, a finding that can lead to stronger, more targeted marketing efforts.

Similarly, a law office might describe its products by listing the number of wills, estate plans, incorporations, bankruptcies, divorces, adoptions, and lawsuits it handles annually. And if it’s well managed, the lawyers will know which of those product lines are profitable and which services are performed at a loss in return for the likelihood of ongoing, profitable relationships.

What about your business?

- What do you sell? How much? How many? What times of year or week or day do your products sell best? How often is a customer likely to buy or use your product?

- What does your product or service do for your customers? How do they use it? How does it make them feel? What problem does it solve?

- How is your offering different from and better than your competitors’?

- How is it better than it was even a year ago?

- What does it cost?

- What do customers do if they’re displeased or if something goes wrong?

By answering these questions, you gain an understanding of your products and the ability to steer their future sales.

When service is your product

If your business is among the great number of companies that sell services rather than three-dimensional or packaged goods, from here on when you see the word product, think service. In your case, service is your product.

Today, nearly 80 percent of all Americans work in service companies. Services — preparing tax returns, writing wills, creating websites, styling hair, or designing house plans, to name a few — aren’t things that you can hold in your hands. In fact, the difference between services and tangible products is that customers can see and touch the tangible product before making the purchase, whereas when they buy a service, they commit to the purchase before seeing the outcome of their decisions, relying heavily on their perception of the reputation of your business.

Your product is what Google says it is

Chances are great that before people contact you or your business directly they check you out online. Close to a hundred million names are searched on Google every day. Before buying products, visiting businesses, or meeting others, people look online to see which businesses dominate the first screens of their search results. You should too.

Customers also look online to see whether their search results turn up credible and trust-building information about your business, including links to positive and descriptive sites and, increasingly, Google +1 recommendations from people they know and regard highly.

Illogical, Irrational, and Real Reasons People Buy What You Sell

Online searches and customer opinion research results reveal what people believe about your product, your product category, what your offering means to them personally, and why they make what otherwise may seem like illogical buying decisions. Think about it:

- Why pay $5 for a loaf at the out-of-the-way Italian bakery if they can buy bread for under a dollar at the grocery store?

- Why pay nearly double for a Lexus than for a Toyota if some models of both are built with many of the same components?

- Why seek cost estimates from three service providers and then choose the most expensive bid if all three propose nearly the same solution?

Why? Because people rarely buy what you think you’re selling.

They buy the $5 loaf of salt-crusted rosemary bread because they believe it’s worth it, perhaps because it tastes superior or maybe because it satisfies their sense of worldliness and self-indulgence. They opt for the high-end car for the feeling of safety, quality, prestige, and luxury it delivers. They pay top price for services perhaps because they like having their name on a prestigious client roster — or maybe because they simply like or trust the high-cost service provider more than the lower-cost ones.

People may choose to buy from your business over another simply because you make them feel better when they walk through your door.

Buying Decisions: Rarely about Price, Always about Value

Customers decide to buy based on their perception of the value they’re receiving for the price they’re paying. Whatever you charge for your product, that price must reflect what your customer thinks your offering is worth. If nothing distinguishes your product, it falls into the category of a commodity, for which customers are unwilling to pay extra.

If a customer thinks your price is too high, expect one of the following:

- The customer won’t buy.

- The customer will buy but won’t feel satisfied about the value, meaning you win the transaction but sacrifice the customer’s goodwill and possibly the chance for repeat business.

- The customer will tell others that your products are overpriced.

- You may sacrifice the sale if the prospect interprets the low price as a reflection of a second-rate offering.

- You may make the sale, but at a lower price (and lower profit margin) than the customer is willing to pay, leaving lost revenue and possibly customer questions following the transaction.

- The customer may leave with the impression that you’re a discounter — a perception that may steer future opinions and purchase decisions.

Calculating the value formula

During the split second it takes for customers to rate your product’s value, they weigh a range of attributes:

- What does it cost?

- What is the quality?

- What features are included?

- Is it convenient?

- Is it reliable?

- Can they trust your expertise?

- How is the product supported?

- What guarantee, promise, or ongoing relationship can they count on?

These considerations start a mental juggling act, during which customers determine your offering’s value. If they decide that what you deliver is average, they’ll expect a low price to tip the deal in your favor. On the other hand, if they rank aspects of your offering well above those of competing options, they’ll likely be willing to pay a premium for the perceived value.

- Costco = Price

- Nordstrom = Service

- 7-Eleven = Convenience

- FedEx = Reliability

- Apple = Quality

Riding the price/value teeter-totter

Price emphasizes the dollars spent. Price is what you get out of the deal. Value is what you deliver to customers. Value is what they care most about and what your communications should emphasize.

Pricing truths

When sales are down or customers seem dissatisfied, small businesses turn too quickly to their pricing in their search for a quick-fix solution. Before reducing prices to increase sales or satisfaction levels, think first about how you can increase the value you deliver. Consider the following points:

- Your customer must perceive your product’s value — or the worth of the solution your product delivers — to be greater than the asking price.

- The less value customers equate with your product, the more emphasis they put on low price.

- The lower the price, the lower the perceived value.

- Customers like price reductions way better than price increases, so be sure when you reduce prices that you can live with the change, because upping prices later may not sit well.

- Products that are desperately needed, rarely available, or one-of-a-kind are almost never price-sensitive.

Penny-pinching versus shooting the moon

Tell a person he needs angioplasty surgery, and he’ll pay whatever the surgeon charges — no questions asked. But tell him he’s out of dishwasher detergent, and he’ll comparison shop. Why? Because one product is more essential, harder to substitute, harder to evaluate, and needed far less often than the other. One is a matter of life and death, the other mundane. See Table 2-3 to determine where your product fits on the price-sensitivity scale.

Table 2-3 Price Sensitivity Factors

Price Matters Less if Products Are |

Price Matters More if Products Are |

Hard to come by |

Readily available |

Purchased rarely |

Purchased frequently |

Essential |

Nonessential |

Hard to substitute |

Easy to substitute |

Hard to evaluate and compare |

Easy to evaluate and compare |

Wanted or needed immediately |

Easy to put off purchasing until later |

Emotionally sensitive |

Emotion-free |

Capable of providing desirable and highly beneficial outcomes |

Hard to link to a clear return-on-investment |

One-of-a-kind |

A dime a dozen |

Evaluating your pricing

Give your prices an annual checkup. Here are factors to consider and questions to ask:

- Your price level: Compared to competitors’ offerings, how does your offering rank in terms of value and price? How easily can the customer find a substitute — or choose not to buy at all? (See Book 1, Chapter 3.)

- Your pricing structure: Do you include or charge extra for enhanced features or benefits? What promotions, discounts, rebates, or incentives do you offer? Do you offer quantity discounts? Does your pricing motivate desired customer behavior, for example by offering a discount on volume purchases, contract renewals, or other incentives that are factored into your pricing to reduce hesitation and inspire future purchases?

- Pricing timetable: How often do you change your pricing? How often do your competitors change their pricing? Do you anticipate competitive actions or market shifts that will affect your pricing? Do you expect your costs to affect your prices in the near future? Do you need to consider any looming market changes or buyer taste changes?

Raising prices

Customers either resist or barely register price hikes. Their reaction largely depends on how you announce the change. One of the worst approaches is to simply raise prices with a take-it-or-leave-it announcement. Far better is to include new pricing as part of a menu of pricing options, following these tips:

- Accompany price hikes with lower-priced alternatives. Examples include bulk-purchase prices, slow-hour or slow-season rates, and bundled product packages that provide a discount in return for the larger transaction.

Announce a new range of products instead of simply high- and low-priced options. Research shows that, though customers often opt for the lower of two price levels, when three price levels are provided, they choose the mid-range or upper level rather than the least expensive.

Announce a new range of products instead of simply high- and low-priced options. Research shows that, though customers often opt for the lower of two price levels, when three price levels are provided, they choose the mid-range or upper level rather than the least expensive.- Give customers choices by unbundling all-inclusive products. By presenting product components and service agreements as self-standing offerings customers can self-tailor a lower-priced offering.

- Give advance notice of price increases. In service businesses, don’t make customers discover increases on their invoices. Allow them time to accommodate new pricing in their budgets. In retail businesses, give customers the opportunity to stock up before price hikes take effect.

- Believe in your pricing. Especially when you raise prices, be certain that your pricing is a fair reflection of your product’s cost and value. Then instill that belief throughout your business.

Presenting prices

The way you present prices can inspire your prospects — or confuse or underwhelm them. Use Table 2-4 and the following advice to show your prices in the most favorable light:

- Don’t let your price presentation get too complex. Table 2-4 presents examples for presenting prices in a straightforward, visually attractive manner that communicates clearly without misleading consumers.

- Do make the price compelling. In a world of outlet malls, online bargains, and warehouse stores, “10 percent off” isn’t considered a deal.

- Do support pricing announcements with positive benefits your product promises to deliver. Price alone is never reason enough to buy.

Table 2-4 Pricing Presentation Do’s and Don’ts

Do |

Don’t |

Why |

Announcing a new St. Louis number to remember — $89 per night |

We’ve just cut our nightly rates — $89 midweek; some restrictions apply |

The first approach makes the deal sound noteworthy, whereas the second approach provides no positive rationale and implies that “small print applies.” |

Sofa and loveseat $1,995 |

Sofa and loveseat $1,995.00 |

When prices are more than $100, drop the decimal point and zeroes to lighten the effect. |

½ off second pair |

25% off two or more |

Complicated discounts are uninspiring, and “½ off” sounds like double the discount of 25% off when you buy two. |

Regularly $995; now $695 while supplies last |

30% off |

A third off sounds more compelling than 30% off, but showing a $300 reduction is stronger yet. “While supplies last” adds incentive and urgency. |

$17.95; we pick up all shipping and handling |

$14.95 plus shipping/handling |

The word “plus” alerts the consumer that the price is only the beginning. Calculate and include shipping and handling to remove buyer concern and possible objection. |

State and local taxes apply |

State and local taxes extra |

“Extra” goes into the same category as “plus” when it comes to pricing. |

The Care and Feeding of a Product Line

You have two ways to increase sales:

- Sell more to existing customers.

- Attract new customers.

Figure 2-1 presents questions to ask as you seek to build business from new and existing customers through new and existing products.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 2-1: Questions to ask as you assess your sales growth options.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

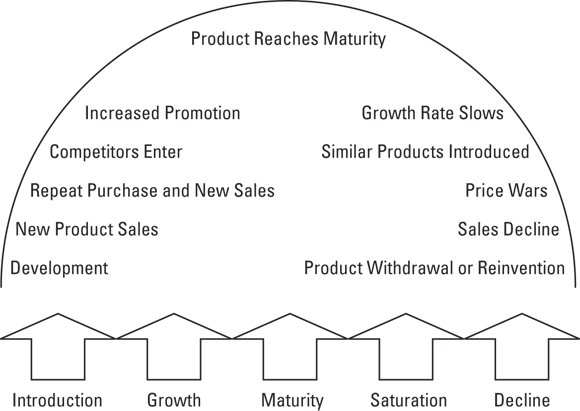

FIGURE 2-2: Sales follow a predictable curve throughout the product life cycle.

Enhancing the appeal of existing products

At least annually, small businesses need to assess whether their products still appeal to customers. When customers lose interest, a company needs to adjust features, services, pricing, or packaging — or make other changes to sustain or reignite buyer interest. Here are some of your options:

Same product, new use: Start by looking for ways you can re-present the product to win new purchases by established and new customers.

A historic example of re-presenting a product comes from Arm & Hammer baking soda. When consumers stopped baking, sales of baking soda tumbled. Arm & Hammer responded by reintroducing baking soda — this time not as a recipe ingredient but rather as a refrigerator deodorizer. Today, that repurposing has led Arm & Hammer into a role as a leading supplier of cleaning and household solutions.

A historic example of re-presenting a product comes from Arm & Hammer baking soda. When consumers stopped baking, sales of baking soda tumbled. Arm & Hammer responded by reintroducing baking soda — this time not as a recipe ingredient but rather as a refrigerator deodorizer. Today, that repurposing has led Arm & Hammer into a role as a leading supplier of cleaning and household solutions.Same product, new promotional offer: Examine ways to update how you offer your product to customers, including new distribution, customer-responsive pricing, or new packages combining top-selling products with others your customers may not have tried.

Be sure your new offer provides advantages that address customer wants and needs. Before you offer a new “deal,” be sure that you can say yes to the following question: Does this provide customers with a better, higher-value way to buy the product? For advice to follow, see the sidebar, “Innovation isn’t for the self-absorbed,” later in the chapter.

Be sure your new offer provides advantages that address customer wants and needs. Before you offer a new “deal,” be sure that you can say yes to the following question: Does this provide customers with a better, higher-value way to buy the product? For advice to follow, see the sidebar, “Innovation isn’t for the self-absorbed,” later in the chapter.- Same product, new customer: Expand the market for existing products through low-risk, introductory trial offers or samples or through free seminars, guest lectures, or events that attract the kinds of people you target as customers and develop their interest in your offerings.

Raising a healthy product

Sales follow a predictable pattern as a product moves through the life cycle illustrated in Figure 2-2. The following descriptions explain the marketing steps and sales expectations that accompany each phase of the product’s life:

Introductory phase: At the beginning of a product’s life cycle, you want to build awareness, interest, and market acceptance while working to change existing market purchase patterns. Use introductory offers to gain trial and drive sales to speed up your cost/investment recovery.

Although prompting early sales through low pricing is tempting be careful, how you introduce a product determines how its image is established. If customers link the product with a low price, that first impression will stick and limit your ability to increase prices later. Better to set the price where it belongs relative to your product value and to gain sales through heavy start-up advertising and, if necessary, carefully crafted promotional offers.

Although prompting early sales through low pricing is tempting be careful, how you introduce a product determines how its image is established. If customers link the product with a low price, that first impression will stick and limit your ability to increase prices later. Better to set the price where it belongs relative to your product value and to gain sales through heavy start-up advertising and, if necessary, carefully crafted promotional offers.- Growth phase: The product enters this phase after it’s adopted by the first 10 to 20 percent of the market, called the innovators or early adopters. The masses follow this pace-setting group, and when the masses start buying, growth takes off and competitors enter. Consider promotions and special offers to protect and build market share.

- Maturity: When the product reaches maturity, its sales are at their peak level, and sales growth starts to decline.

- Saturation phase: At this phase, the market is flooded with options. Sales come largely from replacement purchases. Use pricing offers and incentives to recruit new customers and win them from competitors.

- Declining phase: When the product reaches the point of deep sales decline, a business has only a few choices. One is to abandon the product in favor of new offerings, perhaps introducing phase-out pricing to hasten the cycle closure. Another is to let the product exist on its own with minor marketing support and, as a result, lowered sales expectations. Yet a third option is to reinvent the product’s usage, application, or distribution to gain appeal with a new market; it’s best to take this revitalizing step when a product reaches its maturity rather than after its appeal is in decline.

Developing new products

Whether it’s to seize a new market opportunity or to offset shrinking sales with replacement products, one of the most exciting aspects of business is introducing new products. It’s also one of the most treacherous because it involves betting your business resources on a new idea.

As you pursue product development, ask these questions:

- What current product can you significantly update or enhance to address changing customer wants and needs?

- What altogether new idea will satisfy currently unaddressed wants and needs of your customers and prospective customers?

- What market trend can you address with a new product?

- Only a fraction of hot fads launch marketplace trends. Most come and go quickly, so have a plan to get in and get out of the market quickly if interest ebbs.

- Be sure you aren’t entering the market too late. Take a second to review Figure 2-2, the product life cycle. If other companies have already introduced offerings to address the fad, and if those products have already reached the saturation phase, then your new offering will have to come with pricing and other incentives to win business from the lineup of competitors already in the field.

Here are questions to ask during the research stage of product development:

- Is it unique? Is another business already producing it, and, if so, will your product be materially different — and better?

- Does it deliver customer value? If this is an upgrade of an existing product, how is it different in a way that matters to customers?

- Will it appeal to a growing market? What is its customer profile?

- Is it feasible? What will it cost to produce or deliver, and how much can you charge for it?

- Does it fit with your company image? Is it consistent with what people already believe about you, or does it require a leap of faith?

- Is it legal and safe? Does it conform to all laws? Does it infringe on any patents? Does it have safety concerns?

- Can you make and market it? Do you have the people and cash resources to back it? Can you get it to market? Do sales projections support the cost of development, introduction, and production?

- Features that don’t inspire your customer

- Features that don’t deliver clear customer benefit

- Product enhancements that don’t add significant product value

- “New” products that are really old products in some newfangled disguise that means nothing to customers

- Products that don’t fit within your expertise and reputation

- Products that address fads or trends that are already starting to wane

One last caution: If you’re introducing a product that’s the very first of its kind, budget sufficiently to achieve customer knowledge and a fast following. Otherwise you may lose the advantage to a competitor who arrives second but with a better offering and marketing effort. As proof, consider how AltaVista was eclipsed by Google or how MySpace was overtaken by Facebook.

Managing your product offerings

Product line management is less about what you’re selling than about what the market is buying. Keep your focus on your customers — on what they value — not just today, but tomorrow.

Make a list of products you sell and the revenue that each offering generates. Concentrate only on the end products you deliver. For example, a law office provides clerical services, but because those services are part of other products and aren’t the reason people do business with the attorneys in the first place, they shouldn’t show up on the firm’s product list.

To get you started, Table 2-5 shows products for a bookstore.

Table 2-5 Independent Bookstore Product Line Analysis

Product |

Product Revenue |

Percentage of Revenue |

Books |

$250,000 |

43.4% |

Magazines |

$95,000 |

16.5% |

Coffee and pastries |

$95,000 |

16.5% |

Greeting cards and gift items |

$55,000 |

9.5% |

Audiobooks |

$45,000 |

7.8% |

Audiobook rentals |

$18,500 |

3.2% |

Pens and writing supplies |

$18,000 |

3.1% |

Follow these steps to prioritize and manage your product line:

- Sell more of what customers are buying. Study your list for surprises. You may find some products that are performing better than you realized. This knowledge will alert you to customer interests that you can ride to higher revenues. For example, nearly one-third of all revenues at the bookstore featured in Table 2-5 come from beverage/pastry and magazine sales (combined). This finding may support a decision to move the magazine display nearer to the cafe, giving each area a greater sense of space and bringing consumers of both offerings into nearer proximity (and therefore buying convenience).

- Promote products that you’ve hidden from your customers. You may have a product line that’s lagging simply because your customers aren’t aware of it. When the bookstore in Table 2-5 realized that only 3 percent of revenues were from sales of pens and writing supplies, the owners boosted the line by giving it a more prominent store location. The result? Sales increased. Had the line continued to lag, though, the owners were ready to replace it with one capable of drawing a greater response.

- Move fast-selling items out of prime retail positions. Give the spotlight to harder-to-sell offerings or give the slower-selling items visibility by placing them near top sellers. In the case of the bookstore in Table 2-5, moving a display of greeting cards closer to the popular pastry counter led to increased sales.

- Back your winners. Use your product analysis to track which lines are increasing or decreasing in sales and respond accordingly. If the bookstore in Table 2-5 is fighting a decline in book sales whereas sales of reading accessories and gifts are growing, the owners may decide to address the trend by adding lamps, bookends, and even reading glasses.

- Bet only on product lines that have adequate growth potential. Before committing to new product strategies, project your return on investment. For example, Table 2-5 shows that a little more than 3 percent of sales result from audiobook rentals. Doubling this business would increase annual revenues by only $18,500. Realizing this, the owners asked: What’s the likelihood of increasing this business — and at what cost? On the other hand, increasing cafe sales by 20 percent would realize $19,000 of additional revenue, which the owners determined was a safer marketing bet and a stronger strategic move.

Business leaders don’t work for themselves; they work for their customers.

Business leaders don’t work for themselves; they work for their customers.