Chapter 2

Coordination of EROM with Organizational Management Activities

Although the need for EROM in TRIO enterprises may be driven by a need to provide innovative technical solutions to complex problems, it is also desirable, and often necessary, to implement EROM within the current management framework of the organization. This chapter describes the high-level structure of most TRIO enterprises, the interfaces between the principal entities of these enterprises in the areas of strategic planning, implementation, and evaluation, and the manner in which EROM activities interface with these traditional management activities.

2.1 The Executive, Programmatic, and Institutional/Technical Management Functions and Their Interfaces

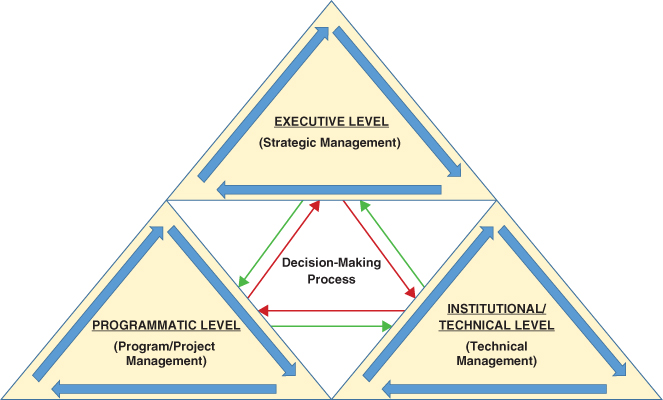

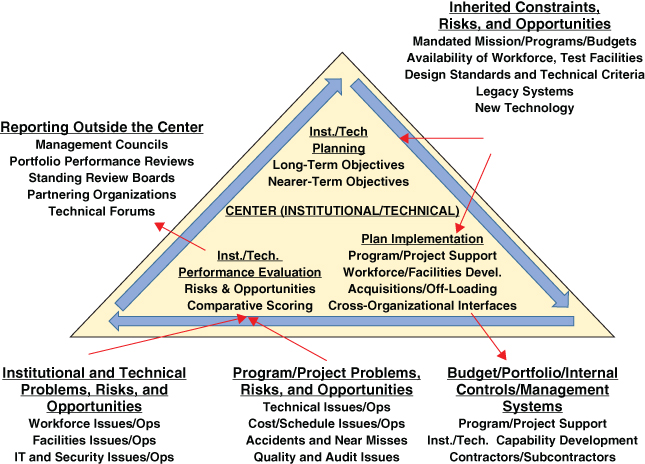

While the detailed organizational and management structure of individual organizations differs, most TRIO enterprises share common top-level organizational entities, management processes, and activities. Generally, as illustrated in Figure 2.1, a TRIO enterprise may be described as comprising three management organizational levels: (1) an executive level that sets and manages the direction and strategy for the enterprise; (2) a programmatic level that develops and manages the programs and projects that support the strategic plan; and (3) an institutional/technical level that develops and manages the institutional and technical resources that support the programs and projects. Decision making involves robust communication within and among all levels.

Figure 2.1 The three levels of management within a typical enterprise

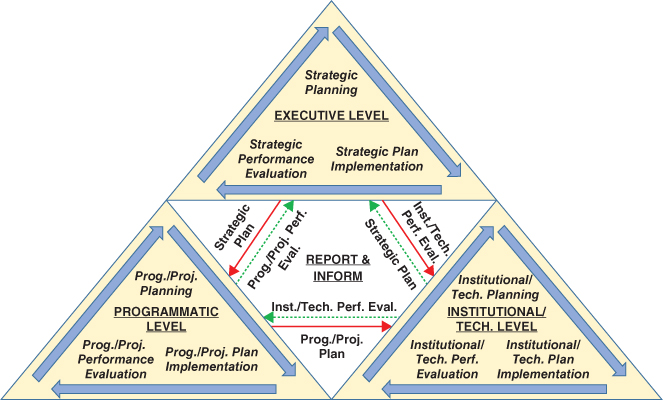

Each of these organizational levels performs a similar set of management activities, as shown in Figure 2.2. These activities include planning, plan implementation, and performance evaluation. At the executive level, management sets the overall strategic objectives, goals, and desired outcomes for the enterprise; develops a plan for implementation, including the definition of major programs and projects and specification of institutional support requirements; evaluates performance in terms of the degree to which its strategic objectives are being realized; and makes major course correction or course resetting decisions when conditions warrant. At the programmatic level, program/project management provides the same goal setting and execution oversight with respect to the programs and projects that the executive level initiates. At the institutional/technical level, technical management does the same for the institutional and technical capabilities of the enterprise, including the sufficiency of the workforce, availability of facilities, and integrity of procurement and quality control practices. The transfer of information between the organizational levels is bidirectional, with the results of the planning activities being communicated in general from executive to programmatic to institutional/technical level, and the results of the evaluation activities being communicated in general from institutional/technical to programmatic to executive level (although the direction of communication may vary according to the nature of the organization).

Figure 2.2 The principal activities and transfer of information within and between levels of management

2.2 EROM-Relevant Management Activities

2.2.1 Activities within Each Management Level

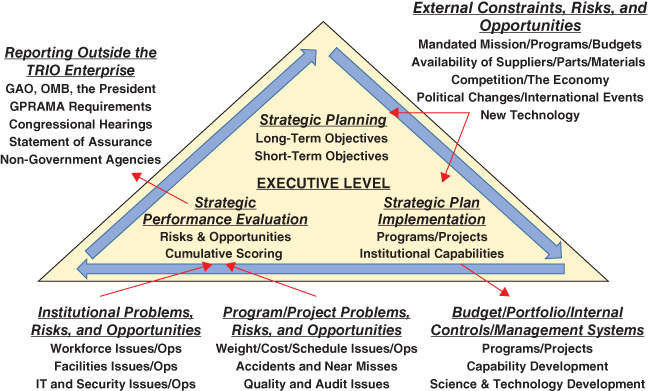

At the executive level, the processes of strategic planning, strategic plan implementation, and strategic performance evaluation are guided by information obtained from both external and internal sources, as shown in Figure 2.3. The information to be gleaned from external sources includes:

Figure 2.3 Activities within the executive level and transfer of information from/to external and internal sources

- Mission priorities, programs/projects, schedules, and budgets that are mandated by external stakeholders and funding authorities, such as Congress and the US president in the case of federal agencies

- Supply constraints such as the availability of suppliers, parts, and materials

- Marketplace constraints such as inflation rates and competition from other entities, both domestic and foreign

- Political constraints, such as the prospects for changes in the federal administration, the makeup of Congress, restrictions on certain foreign entities, or the leadership of nongovernment funding agencies

- Legal constraints, such as new enactments with new requirements or threats of litigation

- The emergence of new technology that may open opportunities for undertaking new objectives or achieving faster progress toward current objectives, or conversely pose new threats (e.g., cyber-security)

In addition, information is transferred from the executive level to entities external to or independent from the TRIO enterprise management structure, such as (for federal agencies) the GAO, the OMB, inspectors general, and Congress, in the form of presentations and reports. The scope and contents of information provided to OMB has to comply with the requirements of GPRAMA as detailed in various OMB circulars.

Information to be received from internal sources (programmatic and institutional/technical levels) includes:

- The status of risks and opportunities for programs/projects, including safety concerns, technical performance concerns, cost concerns, and schedule concerns

- The status of risks and opportunities at the institutional/technical level, including workforce concerns, concerns with facilities and equipment, IT concerns, and security concerns

- Identification and evaluation of risks and opportunities that cut across programs, projects, and institutional/technical entities

- The status of concerns within the programmatic and institutional/technical levels that have evolved from risks to problems, and the status of corrective actions

Correspondingly, information is transferred from the executive level to the programmatic and institutional/technical levels via the strategic plan, and associated back-up material, including in particular the specifications for the agency's portfolio of programs, projects, institutional initiatives, research and development initiatives, resource expectations, schedules and budgets, and so on.

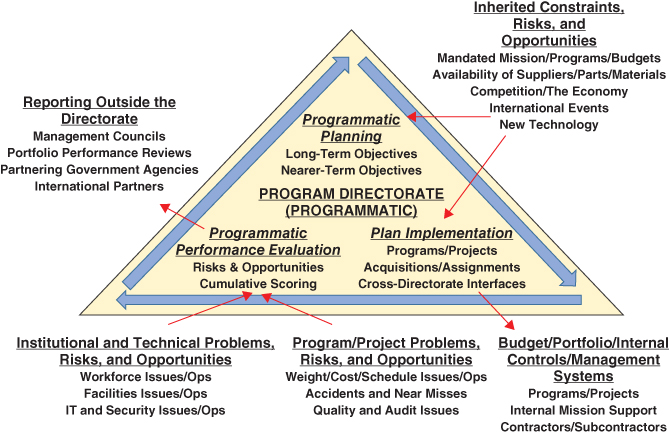

The activities and transfer of information at the programmatic or program directorate level parallel the activities and transfer of information at the executive level, but with the following differences as shown in Figure 2.4:

Figure 2.4 Activities within a program directorate (programmatic level) and transfer of information from/to external and internal sources

- The top objectives are programmatic and, for the most part, are received from the executive level as part of its strategic planning and plan implementation activities.

- The results from the programmatic planning, implementation, and performance evaluation activities are presented to the various governing councils within the TRIO enterprise, which may include (for example) a strategic management council, an executive council, a program management council, and/or a mission support council.

- The results from the programmatic performance evaluation also provide input to portfolio performance reviews.

- Implementation of the programmatic planning activity includes feedback to and from other program directorates, particularly regarding concerns that cut across program directorates.

By and large, the program directorates operate as enterprises, so from a practical point of view, the principles of EROM apply to them as well as to the executive level.

The same is true for the technical centers or directorates,1 as shown in Figure 2.5. The activities and transfer of information at the center level parallel the activities at the program directorate level, except that the top objectives concern institutional and technical capability development as well as support of the programs/projects. These top objectives require the technical centers to concentrate, in their planning processes, upon how to achieve an efficacious balance between services provided directly by them versus services acquired from other entities such as commercial companies, universities, and other agencies.

Figure 2.5 Activities within a technical center (institutional/technical level) and transfer of information from/to external and internal sources

2.2.2 Roles and Responsibilities within and between Each Management Level

Ensuring that managerial roles and responsibilities are clearly defined and that there are no gaps in the assignment of these roles and responsibilities is a major element of enterprise risk management and internal controls. Table 2.1 presents a representative list of roles and responsibilities at the executive, program directorate, and technical directorate levels for a typical TRIO enterprise. The entries in the table were adapted from NASA (2014a) (Table D-1), and they elaborate further on the information conveyed in Figures 2.3 through 2.5.2

Table 2.1 Typical Executive, Program Directorate, and Technical Directorate Managerial Roles and Responsibilities (Adapted from NASA 2014a, Table D-1)

| Category | Responsibility of Executive Management | Responsibility of Executive Management Staff and Advisory Groups | Responsibility of Program Directorates | Responsibility of Technical Directorates (I = Institutional Development, Strategic Support, Program/Project Support, T = Technical Authority) |

| Strategic Planning | Establish enterprise strategic priorities and direction. Approve enterprise strategic plan, programmatic architecture, and top-level guidance. Approve implementation plans developed by program directorates. |

Lead development of enterprise strategic plan. Lead development of annual performance plan. |

Support enterprise strategic planning. Develop program directorate Implementation plan and cross-directorate architecture plans consistent with enterprise strategic plan, programmatic architecture, and top-level guidance. |

Support enterprise and program directorate strategic planning and supporting studies (I). |

| Program/Project Concept Studies | Provide technical expertise for advanced concept studies, as required. | Develop direction and guidance specific to concept studies for formulation of programs and noncompeted projects. | Develop direction and guidance specific to concept studies (I). | |

| Development of Programmatic Requirements | Establish, coordinate, and approve high-level program requirements. Establish, coordinate, and approve high-level project requirements, including success criteria. |

Provide support to program and project requirements development (I). Provide assessments of resources with regard to facilities (I). |

||

| Approve changes to and deviations and waivers from those requirements that are the responsibility of the technical authority and have been delegated to the technical directorate (T). | ||||

| Development of Institutional Requirements | Approve enterprise-level policies and requirements for programs and projects. | Develop policies and procedural requirements for programs and projects and ensure adequate implementation. Approve/disapprove waivers and deviations to requirements under their authority. |

Develop cross-cutting mission support policies and requirements for programs and projects and ensure adequate implementation. Approve/disapprove waivers and deviations to requirements under their authority. |

Develop technical directorate policies and requirements for programs and projects and ensure adequate implementation (I). Develop technical authority policies and requirements for programs and projects and ensure adequate implementation (T). Approve/disapprove waivers and deviations to requirements under their authority (I, T). |

| Budget and Resource Management | Determine relative priorities for use of enterprise resources (e.g., facilities). Establish budget planning controls for program directorates and mission support offices. |

Manage and coordinate enterprise annual budget guidance, development, and submission. Analyze program directorate submissions for consistency with program and project plans and performance. |

Develop workforce and facilities plans with implementing technical directorates. Provide guidelines for program and project budget submissions consistent with approved plans. |

Confirm program and project workforce requirements (I). Provide the personnel, facilities, resources, and training necessary for implementing assigned programs and projects (I). Support annual program and project budget submissions, and validate technical directorate inputs (I). |

| Develop enterprise operating plans and enterprise execute budget. | Allocate budget resources to technical directorates for assigned programs and projects. Conduct annual program and project budget submission reviews. |

Provide resources for review, assessment, development, and maintenance of the core competencies required to ensure technical and program/project management excellence (T). Ensure independence of resources to support the implementation of technical authority (T). |

||

| Program/Project Performance Assessment | Assess program and major project technical, schedule, and cost performance through status reviews. Chair enterprise performance management councils. Chair enterprise-wide baseline program performance reviews. |

Conduct special studies for executive management. Provide independent performance assessments. Administer the enterprise-wide baseline program performance review process. |

Assess program technical, schedule, and cost performance and take action, as appropriate, to mitigate risks. Chair program directorate performance management council. Support the enterprise-wide baseline program performance reviews. |

Assess program and project technical, schedule, and cost performance against approved plans as part of ongoing processes and forums. Chair technical directorate management council (I). Provide summary status to support the enterprise-wide baseline program performance review process and other suitable forums (I). |

| Program Performance Issues | Assess project programmatic, technical, schedule, and cost through performance management council and enterprise-wide baseline program performance review. | Maintain issues and risk performance information. Track project cost and schedule performance. Manage project performance reporting to external stakeholders. |

Communicate program and project performance issues and risks to executive management and present plan for mitigation or recovery. | Monitor the technical and programmatic progress of programs and projects to help identify issues as they emerge (I). Provide support and guidance to programs and projects in resolving technical and programmatic issues and risks (I). |

| Proactively work with the program directorates, programs, projects, and other institutional authorities to find constructive solutions to problems (I). Direct corrective actions to resolve performance Issues (I). |

||||

| Key Decision Points (KDPs) | Authorize program and major projects to proceed past KDPs. | Provide executive secretariat function for KDPs, including preparation of final decision memorandum. | Authorize programs and major projects to proceed past KDPs. Provide recommendation for programs and major projects at KDPs, including proposing cost and schedule commitments. |

Perform supporting analysis to confirm readiness leading to KDPs for programs and all projects (I). Conduct readiness reviews leading to KDPs for all projects (I). Present technical directorate's assessment of readiness to proceed past KDPs, adequacy of planned resources, and ability of technical directorate to meet commitments (I). Engage in major replanning or rebaselining activities and processes, ensuring constructive communication and progress between the time it becomes clear that a replan is necessary and the time it is formally put in place (I). |

2.3 Coordination of EROM with Management Activities

2.3.1 Organizational Planning and Plan Implementation

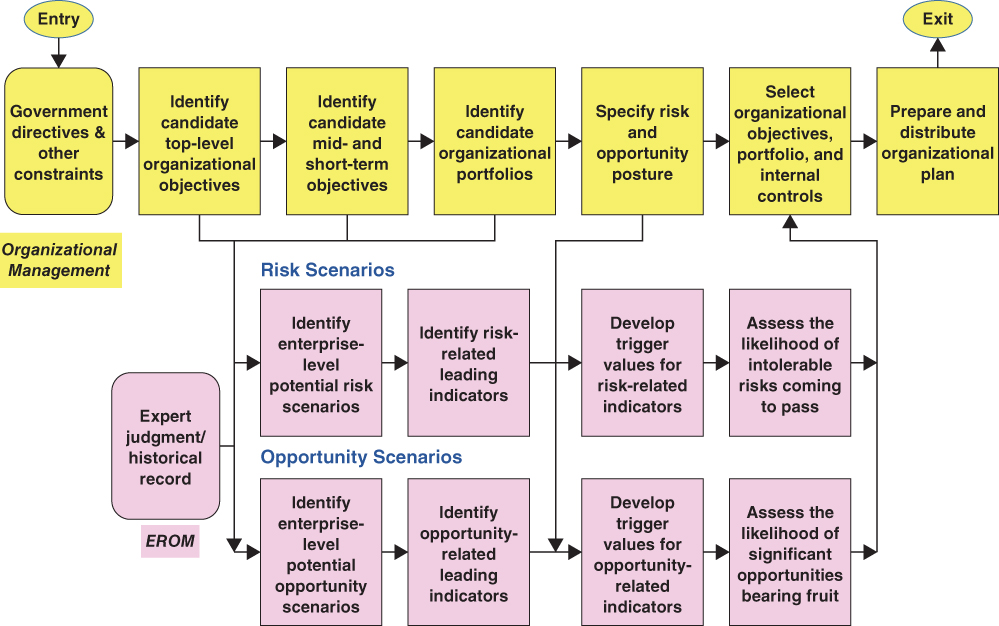

The manner in which EROM assists management at all three levels in developing a responsive and achievable plan is illustrated in Figure 2.6. Following is a brief summary of the activities depicted in this figure:

Figure 2.6 Interfaces between EROM activities and management activities in the development of an organizational plan

Management activities that provide input to the EROM process include:

- Understand and comply with external constraints such as mandated missions and programs, mandated budgets, the availability of suppliers and parts or materials, and legal realities.

- Identify alternative objectives hierarchies that comply with the external constraints and have the potential for achieving the organization's mission in all time frames.

EROM activities that provide input to the management activity of selecting among alternative objectives and preparing the organizational plan include:

- Characterize and understand all relevant historical experience pertaining to failures, successes, precursors, anomalies, unexpected benefits, and lessons learned.

- Identify risks and opportunities for each alternative set of objectives based on the historical record and expert judgment.

- From past experience and current risk/opportunity leading indicators, assess the state of risks/opportunities as they pertain to the likelihood of achieving each objective.

- Risk-inform the selection and application of internal controls.

2.3.2 Evaluation of Organizational Performance and Replanning

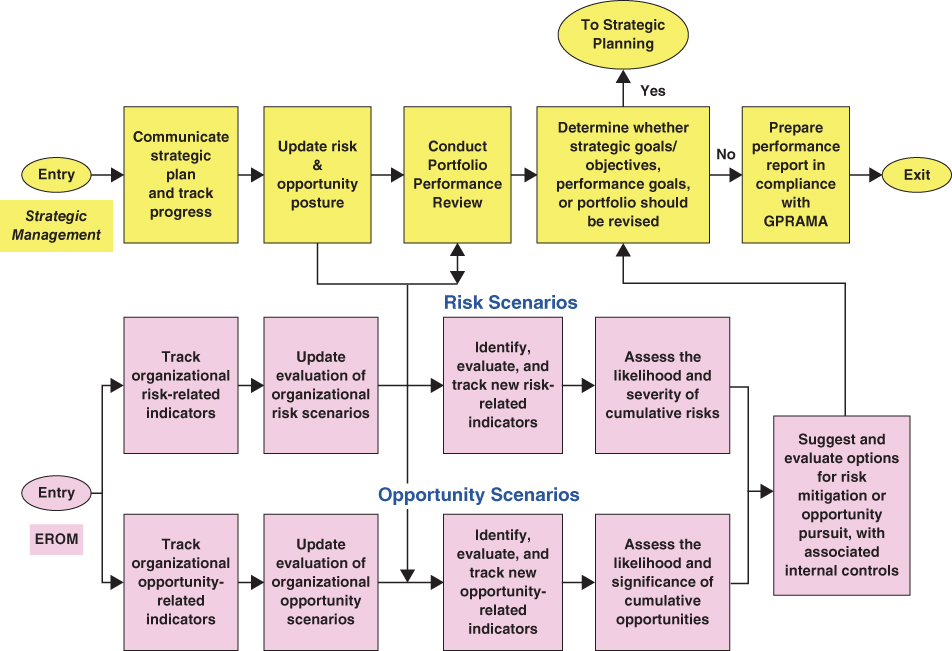

The evaluation of performance at the various management levels also involves close coordination between management activities and EROM activities. From an EROM perspective, the activities that support performance evaluation are similar to the activities that support organizational planning in the sense that both involve the identification and evaluation of risks and opportunities. As discussed in Section 1.2.2, the key difference is in the level of maturity that exists in the definition of risks and opportunities.

The manner in which EROM assists management in evaluating organizational performance is illustrated in Figure 2.7. Following is a brief summary of the activities depicted in that figure:

Figure 2.7 Interfaces between EROM activities and management activities in the evaluation of performance relative to the organizational plan

Management activities that provide input to the EROM process include:

- Track progress on individual programs, projects, institutional initiatives, and other activities in the portfolio with respect to meeting the mid- and short-term objectives in the organizational objectives hierarchy.

- Conduct a portfolio performance review (PPR) at periodic intervals to assess overall adherence to the performance plan and to identify and evaluate cross-cutting issues.

EROM activities that provide input to the management activity of conducting the portfolio performance review include:

- Track leading indicators that pertain to organizational risks and opportunities. (Note that executive-level risks and opportunities generally emanate from external sources such as political, economic, or regulatory changes, whereas risks and opportunities at lower management units generally emanate from internal sources such as the depletion of reserves and margins in any of the mission execution domains: safety, technical performance, schedule, and cost.)

- From the current values of the leading indicators, assess the significance of the risks and opportunities at each level in the organizational objectives hierarchy.

EROM activities that provide input to the management activity of evaluating organizational performance include:

- Identify and track internal performance measures and internal/external leading indicators of risks and opportunities that pertain to the mid- and short-term organizational objectives.

- From the current values of the performance measures and leading indicators and their observed trends, assess the state of risks and opportunities as they pertain to the likelihood of achieving the top organizational objectives.

- When risks are of concern, or when opportunities are attractive, perform an analysis to suggest options that may be pursued to mitigate risks or pursue opportunities and identify associated internal controls.

With these inputs in hand, management has a solid basis for determining whether the organization's objectives are being achieved and whether there are imposing reasons (either positive or negative) for amending or changing some of the objectives and/or portfolio elements. The organization also is in a better position to prepare performance reports and presentations of the type required by the external stakeholders and funding agencies.

2.3.3 Alignment with Management-Level Roles and Responsibilities

Table 2.2 provides a more detailed itemization of EROM activities to support the various management levels of a TRIO enterprise consistent with the roles and responsibilities listed in Table 2.1. The entries in the table elaborate further on the information conveyed in Figures 2.6 and 2.7.

Table 2.2 Executive, Program Directorate, and Technical Directorate Standards of Support to Be Provided by EROM Consistent with Roles and Responsibilities Outlined Previously

| No. | Executive (E) Level | Program Directorate (PD) Level | Technical Directorate (TD) Level |

| 1 (Strategic Planning) |

When E-level strategic objectives have been formulated and enterprise-wide programmatic and mission support architectures are being considered:

|

When PD-level objectives have been formulated and PD-level program/project architectures are being considered:

|

When TD-level objectives have been formulated and institutional and mission support architectures are being considered:

|

| 2 (Strategic Planning) |

When PD-level and TD-level risks and opportunities have been identified and their significance has been estimated:

|

When program/project risks and opportunities have been identified and their significance has been estimated:

|

When program/project and institutional risks and opportunities have been identified and their significance has been estimated:

|

| 3 (Strategic Planning) |

When the risks and opportunities have been rolled up to E level:

|

When the risks and opportunities have been rolled up to PD level:

|

When the risks and opportunities have been rolled up to TD level:

|

| 4 (Strategic Planning) |

When the viability of each proposed enterprise programmatic and mission support architecture has been assessed:

|

When the viability of each proposed PD program/project architecture has been assessed:

|

When the viability of each proposed TD institutional and mission support architecture has been assessed:

|

| 5 (Program/Project Concept Studies) |

When programmatic and institutional architectures have been selected at all levels and concept studies are occurring:

|

When program/project architectures have been selected and concept studies are occurring:

|

When institutional and mission support architectures have been selected and concept studies are occurring:

|

| 6 (Development of Programmatic and Institutional Requirements) |

When programmatic and institutional requirements are being developed:

|

When programmatic and institutional requirements are being developed:

|

When programmatic and institutional requirements are being developed:

|

| 7 (Budget and Resource Management) |

When E-level budgets are being established and resources are being allocated:

|

When MD-level budgets are being established and resources are being allocated:

|

When TD-level budgets are being established and resources are being allocated:

|

| 8 (Enterprise and Program/Project Performance Assessment and Issue Management) |

When the enterprise's performance relative to its established strategic objectives is being assessed:

|

When the PD's performance relative to its established objectives is being assessed:

|

When the TD's performance relative to its established objectives is being assessed:

|

| 9 (Enterprise and Program/Project Performance Assessment and Issue Management) |

When PD-level and TD-level risks and opportunities have been updated and their significance has been estimated:

|

When program/project risks and opportunities have been updated and their significance has been estimated:

|

When program/project and institutional risks and opportunities have been updated and their significance has been estimated:

|

| 10 (Enterprise and Program/Project Performance Assessment and Issue Management) |

When the risks and opportunities have been rolled up to E level:

|

When the risks and opportunities have been rolled up to PD level:

|

When the risks and opportunities have been rolled up to TD level:

|

| 11 (Enterprise and Program/Project Performance Assessment and Issue Management) |

When the viability of each proposed solution or control option for E-level performance issues has been assessed:

|

When the viability of each proposed solution or control option for PD-level performance issues has been assessed:

|

When the viability of each proposed solution or control option for TD-level performance issues has been assessed:

|

| 12 (Acceptance Criteria for Key Decision Points) |

When the enterprise has to make decisions about risk acceptance at key decision points:

|

When the PD has to make decisions about risk acceptance at key decision points:

|

When the TD has to make decisions about risk acceptance at key decision points:

|

2.4 Communication across Extended Partnerships

2.4.1 Nature of the Strategic Objectives That Require Extended Partnerships

Large not-for-profit and government TRIO organizations tend to have a diversity of strategic objectives that go beyond technical and scientific accomplishments related to the prime mission to geopolitical, macroeconomic, and societal objectives that require extensive collaboration. Following, for example, are several strategic objectives (S.O.s) from NASA's strategic plan that fall into this category (emphasis added to highlight the point):

- [S.O. 1.1] Expand human presence into the solar system and to the surface of Mars to advance exploration, science, innovation, benefits to humanity, and international collaboration.

- [S.O. 1.2] Conduct research on the International Space Station (ISS) to enable future space exploration, facilitate a commercial space economy, and advance the fundamental biological and physical sciences for the benefit of humanity.

- [S.O. 1.3] Facilitate and utilize US commercial capabilities to deliver cargo and crew to space.

- [S.O. 1.7] Transform NASA missions and advance the Nation's capabilities by maturing crosscutting and innovative technologies.

- [S.O. 2.4] Advance the Nation's STEM education and workforce pipeline by working collaboratively with other agencies to engage students, teachers, and faculty in NASA's missions and unique assets.

Objectives such as these require TRIO enterprises to work collaboratively with other US agencies, foreign agencies, commercial entities, and educational entities. Most of the collaboration takes place within projects, programs, and special activities (such as new technology development) that are designed to satisfy the strategic objectives of the managing organization.

2.4.2 The Challenges of Conducting EROM across Extended Partnerships

Implementing an effective EROM process within an enterprise that depends on extended partnerships can be challenging. For example, according to a deputy director for US Department of Defense's National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (Holzer 2006), writing about the practice of EROM across extended partnerships: “Culture resistance to change and unwillingness to share information viewed as negative prevail. There is additional complexity convincing people to adopt a process that is part of the bigger organization and sharing information regarding their ability to achieve program objectives.”

In general, the following attitudinal and operational perspectives are needed to accomplish a satisfactory implementation of EROM when extended partnerships are involved (Holzer 2006; Perera 2002):

- Managers within each of the partners need to be convinced that making risk known to all participants in the extended partnership will be positively recognized and at times rewarded with an allocation of risk mitigation funds.

- Partners whose components or systems are being integrated with those of other partners need to be convinced that it is to their benefit to collaboratively and cooperatively manage risks evolving from the integrated relationships.

- When joining enterprises managed by distinctly different organizations to create an extended partnership, diverse leaderships, objectives, motivations, and other cultural views (and ways of doing risk management) need to be melded in accordance with proprietary, security, foreign dissemination (ITAR), and other considerations.

According to various sources, the single most important factor for achieving buy-in across an extended partnership is for senior leaders of each partnering organization, especially at the top level, to repeatedly voice their support and enforce accountability for an integrated risk and opportunity management process across the partnership.3

2.5 Contribution of EROM to Compliance with Federal Regulations and Directives

This section describes how the implementation of an EROM approach for federal agencies is directly relevant to management and reporting requirements and guidelines that have been issued by the legislative and executive branches of the federal government through the GPRAMA Act and OMB Circulars A-11 and A-123.

2.5.1 OMB Circular A-11 and GPRAMA (Government Performance, Results, and Budgeting)

The July 2016 release of OMB Circular A-11 (OMB 2016a) has several new sections devoted to enterprise risk management. Following are three relevant quotations from these sections:

- Section 270.24 states that “Enterprise risk management (ERM) is an effective agency-wide approach to addressing the full spectrum of the organization's significant risks by understanding the combined impact of risks as an interrelated portfolio, rather than addressing risks only within silos. ERM provides an enterprise-wide, strategically-aligned portfolio view of organizational challenges that provides better insight about how to most effectively prioritize and manage risks to mission delivery.”

- Section 270.25 states that “ERM is a strategic discipline that can help agencies to properly identify and manage risks to performance, especially those risks related to achieving strategic objectives. An organizational view of risk positions allows the agency to quickly gauge which risks are directly aligned to achieving strategic objectives, and which have the highest probability of impacting mission When well executed, ERM improves agency capacity to prioritize efforts, optimize resources, and assess changes in the environment.”

- Section 270.26 states that “While agencies are not required to have a CRO [chief risk officer] or enterprise risk management function, they are expected to manage risks to mission, goals, and objectives of the agency. Where applicable, a CRO or other person designated with these responsibilities may serve as a strategic advisor to the COO [chief operating officer] and other staff on the integration of risk management practices into day-to-day business operations and decision-making.”

GPRAMA and OMB Circular A-11 also talk about leading indicators that enable the agency to show that it is on track with respect to meeting its goals and objectives, and in cases where it is not on track, to understand the causes of difficulty and how they can be corrected. The GPRAMA legislation contains the following provisions that are relevant to this discussion:

- In Paragraph 306: “The head of each agency shall make available on the public website of the agency a strategic plan [that] shall contain…an identification of those key factors external to the agency and beyond its control that could significantly affect the achievement of the general goals and objectives.”

- In Paragraph 1121: “Use…performance information to achieve agency priority goals…[and] for agency priority goals at greatest risk of not meeting the planned level of performance, identify prospects and strategies for performance improvement, including any needed changes to agency program activities, regulations, policies, or other activities.

Amplification provided in OMB Circular A-11 includes the following observations:

- In Section 200.21, “Other indicators [are] indicators not used in a performance goal or Agency Priority Goal statement but are used to interpret agency progress or identify external factors that might affect that progress.”

- Also in Section 200.21, “Outcome [indicators are] a type of measure that indicates progress against achieving the intended result of a program [and that] indicates changes in conditions that the government is trying to influence.”

The indicators referred to here may be inferred to be risk leading indicators because they focus on factors that impede progress toward future results.

In addition, OMB Circular A-11 talks about the desirability of pursuing opportunity. Quoting from the Executive Summary:

- “The Administration expects agencies to set a limited number of ambitious goals that encourage innovation and adoption of evidence-based strategies. Agency leaders at all levels of the organization are accountable for choosing goals and indicators wisely and for setting ambitious, yet realistic targets. Wise selection of goals and indicators reflects careful analysis of the characteristics of the problems and opportunities an agency seeks to influence to advance its mission.”

- “As important as it is to sustain a strong performance culture through the practices described in the guidance, it is equally important to have reliable and effective processes which support continuous improvement and opportunities for capacity building.”

The principal ways in which EROM helps ensure compliance with GPRAMA and with the OMB Circular is through the emphasis it provides in having a robust process for selecting goals and objectives both long-term and short-term, in considering risk and opportunity leading indicators to evaluate the likelihood of success, and in placing opportunity pursuit on an equal basis with risk control. These facets of EROM are apparent from Figures 2.6 and 2.7.

2.5.2 EROM and Internal Controls from the Viewpoint of Federal Regulations and Guidance

Under the new federal regulations and related guidance, the activities involved in conducting EROM are intimately related to and mutually supportive of the activities involved in specifying, implementing, and maintaining internal controls.

According to Circular A-11 (OMB 2016a), “Internal controls are the organization, policies, and procedures that [an] agency uses to reasonably ensure that:

- Programs achieve their intended results.

- Resources used are consistent with agency mission.

- Programs and resources are protected from waste, fraud, and mismanagement.

- Laws and regulations are followed.

- Reliable and timely information is obtained, maintained, reported and used for decision making.”

Within the context of EROM, internal controls can be viewed as processes that the organization decides to implement to provide defense-in-depth against risks and to promote successful achievement of its strategic goals and objectives. The overall set of responses to risks and opportunities may include additions or modifications to the design, fabrication, assembly, testing, and operation of a system to mitigate risks and exploit opportunities within the framework discussed earlier. Internal controls focus on processes, procedures, and protocols that make it possible for the overall set of responses to succeed.

According to COSO (2004), “Internal control is encompassed within and an integral part of enterprise risk management. Enterprise risk management is broader than internal control, expanding and elaborating on internal control to form a more robust conceptualization focusing more fully on risk.”

Some typical examples of internal controls are cited in the last previous version of OMB Circular A-123, as follows (OMB 2004):

- “Policies and procedures;

- Management objectives (clearly written and communicated throughout the agency);

- Planning and reporting systems;

- Analytical review and analysis;

- Segregation of duties (separate personnel with authority to authorize a transaction, process the transaction, and review the transaction);

- Physical controls over assets (limited access to inventories or equipment);

- Proper authorization;

- Appropriate documentation and access to that documentation.”

These controls tend to focus heavily on protecting programs and resources from waste, fraud, and mismanagement and on protecting entities from legal liability. In addition to these, the identification, tracking, and analysis of risk leading indicators is another type of internal control that addresses an organization's strategic risk and helps the organization to achieve its mission. This type of internal control is addressed more fully in the most recent issuances of Circulars A-123 and A-11.

In the realm of strategic planning, there are risks pertaining to the setting of objectives (such as failing to have reliable information from external entities), and there are controls to manage those risks (such as ensuring that reliable information is obtained and provided to those responsible for setting the objectives). Failure to have the correct information may also affect the ability to conduct effective risk management once the objectives have been decided on. There should be controls to address these risks as well (Marks 2013).

In determining whether a particular control should be established, the risk of failure and the significance of the opportunity are considered along with the related costs (COSO 2004). For example, it may not be cost-effective for a TRIO enterprise to install sophisticated inventory controls to monitor levels of raw material if the cost of the raw material used in a production process is low, the material is not perishable, ready supply sources exist, and storage space is readily available. Excessive controls that do not address significant risks or opportunities are likely to be costly and unproductive. In addition, they may actually increase risk due to the added burden of having to implement an unnecessary control.

Figure 2.8 The relationship between governance, enterprise risk management, and internal controls according to the new OMB Circular A-123

2.5.3 OMB Circular A-123 (Management's Responsibility for ERM and Internal Control) and the Required Statement of Assurance

OMB Circular A-123 (OMB 2016b) concerns management's responsibility for integrating internal control with enterprise risk management. The memorandum introducing the new circular to the various government agencies states that the intent of the changes from the previous version is “to modernize existing efforts by requiring agencies to implement an Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) capability coordinated with the strategic planning and strategic review process established by GPRAMA, and the internal control processes required by FMFIA [Federal Managers Financial Integrity Act] and Government Accountability Office (GAO)'s Green Book.” The tenor of the new circular is intentionally at a high level to allow each agency the latitude of developing approaches that are applicable to it.

OMB (2016b) views internal controls as being contained within enterprise risk management, and the latter as being contained within governance (see Figure 2.8). As stated in OMB (2016b): “Most agencies should build their capabilities, first to conduct more effective risk management, then to implement ERM, rating those risks in terms of impact, and finally building internal controls to monitor and assess the risk developments at various time points.” Furthermore: “To provide governance for the risk management function, agencies may use a Risk Management Council (RMC) to oversee the establishment of the Agency's risk profile, regular assessment of risk, and development of appropriate risk response.”

The broad governance structure of the federal government is defined through a variety of sources, and in particular, according to OMB (2016b), the “core governance processes are defined by…OMB budget guidance, such as OMB Circular No. A-11, which defines the processes by which the Executive Branch develops and executes Strategic Plans, compiles the President's Budget request, assembles Congressional Budget Justifications, conducts performance reviews, and issues Annual Performance Plans and Annual Program Performance Reports.”

According to OMB (2016b), each federal agency is required to submit a statement of assurance (SoA) that “represents the agency head's informed judgment as to the overall adequacy and effectiveness of internal control within the agency.” According to NASA (2014b), “GAO and OMB are seeking to clarify existing guidance on internal controls…In the past, this review has been largely focused on financial [matters]…The clarifying guidance also seeks to more constructively focus on the concepts of integrated informed risk/risk-based system of internal controls that is not new but previously overshadowed by the financial focus.”

OMB (2016b) emphasizes the importance of having appropriate enterprise risk management processes and systems to identify challenges early, to bring them to the attention of agency leadership, and to develop solutions. It synthesizes existing EROM material mainly from COSO and from the UK Orange Book (2004) while relying on the GAO Green Book (GAO 2014a) as the primary source for the principles relating to internal controls. As described earlier in Section 1.1.4 of this book, COSO provides an overarching EROM framework that is particularly relevant to private enterprise. The Orange Book, correspondingly, offers an EROM framework that is relevant to federal agencies especially in the United Kingdom. The technical references to the Orange book in the new OMB Circular A-123 mainly concern the derivation of risk profiles and the development of models of EROM defined largely in terms of the relationships between different entities.

The following statements are direct quotations (with emphasis added by the author) highlighting some of the new requirements placed by Circular A-123 on federal agencies:

- “[The circular] requires agencies to integrate risk management and internal control functions.”

- “Federal leaders and managers are responsible…for implementing management practices that can effectively identify, assess, mitigate, and report on risks.”

- “Annually, agencies must develop a risk profile coordinated with their annual strategic reviews.”

- “[Risk profiles should] identify risks arising from mission and mission-support operations.”

- “A portfolio view of risk [should provide] insight into all areas of organizational exposures to risk, such as reputational, programmatic, performance, financial, information technology, acquisitions, human capital, etc.”

- “For those objectives for which formal internal control activities have been identified as part of the Risk Profile, assurances on internal control processes must be presented in its Annual Financial Report (AFR) or Annual Performance Report (APR), along with a report on identified material weaknesses and corrective actions.”

- “Agencies should develop a “maturity model approach” to the adoption of an ERM framework.”

- “For FY 2016, Agencies are encouraged to develop an approach to implement ERM. For FY 2017 and thereafter Agencies must continuously build risk identification capabilities into the framework to identify new or emerging risks, and/or changes in existing risks.”

2.5.4 Example Risk Profile from OMB Circular A-123

One of the principles in Circular A-123 pertaining to the development of the risk profile is that the assessment should “ensure that there is a clearly structured process in which both likelihood and impact are considered for each risk.” Table 1 of OMB (2016b) provides an example of a risk profile that specifically reports likelihood and impact as separate items for both inherent risk (the risk before instituting internal controls) and residual risk (the risk after instituting internal controls). The example is reproduced here in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3 Example Risk Profile from the New OMB-Circular A-123

| STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE—Improve Program Outcomes | ||||||||

| Risk | Inherent Assessment | Current Risk Response | Residual Assessment | Proposed Risk Response | Owner | Proposed Risk Response Category | ||

| Impact | Likelihood | Impact | Likelihood | |||||

| Agency X may fail to achieve program targets due to lack of capacity at program partners. | High | High | REDUCTION: Agency X has developed a program to provide program partners technical assistance. | High | Medium | Agency X will monitor capacity of program partners through quarterly reporting from partners. | Primary—Program Office | Primary—Strategic Review |

| OPERATIONS OBJECTIVE—Manage This Risk of Fraud in Federal Operations | ||||||||

| Contract and Grant fraud. | High | Medium | REDUCTION: Agency X has developed procedures to ensure contract performance is monitored and that proper checks and balances are in place. | High | Medium | Agency X will provide training on fraud awareness, identification, prevention, and reporting. | Primary—Contracting or Grants Officer | Primary—Internal Control Assessment |

| REPORTING OBJECTIVE—Provide Reliable External Financial Reporting | ||||||||

| Risk | Inherent Assessment | Risk Response | Residual Assessment | Proposed Action | Owner | Proposed Action Category | ||

| Impact | Likelihood | Impact | Likelihood | |||||

| Agency X identified material weaknesses in internal control. | High | High | REDUCTION: Agency X has developed corrective actions to provide program partners technical assistance. | High | Medium | Agency X will monitor corrective actions in consultation with OMB to maintain audit opinion. | Primary—Chief Financial Officer | Primary—Internal Control Assessment |

| COMPLIANCE OBJECTIVE—Comply with the Improper Payments Legislation | ||||||||

| Program X is highly susceptible to significant improper payments. | High | High | REDUCTION: Agency X has developed corrective actions to ensure improper payment rates are monitored and reduced. | High | Medium | Agency X will develop budget proposals to strengthen program integrity. | Primary—Program Office | Primary—Internal Control Assessment and Strategic Review |

As stated in OMB (2016b), “While agencies can design their own appropriate categories, for the purposes of this guidance the following illustrative definitions can be used.” For impact:

- “High: the impact could preclude or highly impair the entity's ability to achieve one or more of its objectives or performance goals;

- “Medium: the impact could significantly affect the entity's ability to achieve one or more of its objectives or performance goals; and

- “Low: the impact could not significantly affect the entity's ability to achieve each of its objectives or performance goals;”

and for likelihood:

- “High: the risk is very likely or reasonably expected to occur;

- “Medium: the risk is more likely to occur than unlikely; and

- “Low: the risk is unlikely to occur.”

An alternative suggested ranking process more suitable for TRIO enterprises will be presented and discussed in Section 3.6.3.

Notes

References

- Benjamin, A., Dezfuli, H., and Everett, C. 2015. “Developing Probabilistic Safety Performance Margins for Unknown and Underappreciated Risks,” Journal of Reliability Engineering and System Safety. Available online from ScienceDirect.

- Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). 2004. Enterprise Risk Management—Integrated Framework: Application Techniques.

- GAO-14-704G. 2014a. The Green Book, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Accounting Office. (September).

- Holzer, T. H. 2006. “Uniting Three Families of Risk Management—Complexity of Implementation x 3,” INCOSE International Symposium 16 (1): 324–336. Also available from National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. (July).

- International Standard ISO/FDIS 31000. 2008. Risk Management—Principles and Guidelines.

- Marks, Norman. 2013. “Is Risk Management Part of Internal Control or Is It the Other Way Around?” The Institute of Internal Auditors (May). www.theiia.org.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 2008. NPR 8000.4A. “Agency Risk Management Procedural Requirements.” http://nodis3.gsfc.nasa.gov/displayDir.cfm?t=NPR&c=8000&s=4A

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 2014a. NASA/SP-2014-3705. NASA Space Flight Program and Project Management Handbook. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 2014b. “NASA Internal Control Program Statement of Assurance (SoA) Process Manual Fiscal Year 2014.” (May 2).

- Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2004. OMB Circular A-123. “Management's Responsibility for Internal Control.” https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/omb/circulars/a123/a123_rev.pdf

- Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2016a. OMB Circular A-11. “Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget.” (July) https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/a11_current_year/a11_2016.pdf

- Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2016b. OMB Circular A-123. “Management's Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control.” (July) https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/memoranda/2016/m-16-17.pdf

- The Orange Book, Management of Risk—Principles and Concepts. October 2004. United Kingdom: HM Treasury.

- Perera, J. S. 2002. “Risk Management for the International Space Station.” Joint ESA-NASA Space-Flight Safety Conference, European Space Agency, ESA SP-486. Also available from NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS).