Chapter 5

Management and Implementation of EROM at the Institutional/Technical Level (Technical Centers or Directorates)

5.1 EROM from a Technical Center's Perspective

As discussed previously in Section 1.1.7, EROM can be applied separately to management units within a TRIO enterprise so long as the objectives of each management unit are consistent with the objectives of the enterprise as a whole, and the cross-cutting risks and opportunities are handled consistently. Since the top objectives of a technical center or technical directorate are derived from the TRIO enterprise's strategic objectives, the top objectives of the center are consonant with those of the enterprise in all areas where the center's roles align with the enterprise's responsibilities.

To support the TRIO enterprise's strategic objectives, technical centers may have multiple roles. They may act as managers of programs and projects that are assigned to them by the program directorates, as contributors to programs and projects as requested when another technical center has management responsibilities, as preservers of core competencies required to support programs and projects, as preservers of other core competencies mandated by the executive level, and as support agents for special needs levied on the enterprise by other entities such as the federal government. In the role of managers of programs and projects assigned to them, they may also act as integrators and arbitrators of an extended organization that includes other technical centers, prime contractors, other commercial suppliers, university partners, and international partners. Furthermore, as was illustrated in Figure 2.5, implementing a technical center's plan includes developing and managing the workforce, maintaining needed facilities and retiring unneeded ones, acquiring services and material, and off-loading responsibilities when appropriate to the partnering agencies and companies. Chapter 5 focuses on these areas in developing guidance for the conduct of EROM at the institutional/technical level—that is, technical centers.

The particular objectives of EROM at the technical center level vary as the roles of the center vary. For example, when the technical center is exercising its role as a manager of programs and projects, the principal objective of EROM is to integrate the risks and opportunities discovered by the multiple organizations contributing to the program/project, ensuring that they are handled consistently across the program/project and across the center, that cross-cutting risks and opportunities are accounted for, that the contributions of individual risk and opportunity scenarios are aggregated appropriately from lower levels to higher levels, and that responses such as mitigation of risks and exploitation of opportunities are coordinated. On the other hand, when it is exercising its role as preserver of core competencies, the principal EROM objective is its primary institutional objective: to optimize the acquisition, allocation, and retirement of the various assets available to the technical center, including human assets (the workforce), physical assets (facilities, equipment, systems, and software), and instructional assets (policies, requirements, standards, and guidance).

5.2 Extended Enterprises and the Technical Center's Extended Organization

5.2.1 Overview

The example demonstration used in Chapter 4 is an instance of a project that involves multiple partners, or entities, with overlapping responsibilities. The collection of these entities is referred to herein as an extended enterprise, because in addition to contributing to the same project, each is an independent enterprise with its own set of strategic objectives and performance requirements. Consider, for example, the extended enterprise for the NASA JWST project, shown in Table 5.1. The center that manages the project (Goddard Space Flight Center) must communicate with the extended enterprise in a manner that satisfies the strategic objectives of the TRIO enterprise (NASA) while also respecting the strategic objectives of each of the contributing entities. Other centers within the extended enterprise (those identified in Table 5.1) also must communicate with the other entities they interface with.

Table 5.1 Distribution of Responsibilities among the Principal Entities within the JWST Project (Source: NASA 2016c)

| Entity | Responsibility |

| NASA Centers: | |

| Goddard (GSFC) | Manages the JWST project and provides Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM) components |

| Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) | Manages the Mid-Infrared Instrument |

| Ames (ARC) | Detector technology development |

| Johnson (JSC) | Provides observatory test facilities |

| Marshall (MSFC) | Mirror technology development and environmental research |

| Glenn (GRC) | Cryogenic component development |

| Industry Partners: | |

| Northrop Grumman (NGC) | Prime contractor |

| Ball Aerospace | In charge of building the mirrors |

| COM DEV International | In charge of the Fine Guidance Sensor (FGS) |

| Academic Partners: | |

| Space Telescope Science Inst. | Science and Operations Center at Johns Hopkins University |

| University of Arizona | In charge of building the Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) |

| International Partners: | |

| European Space Agency (ESA) | Provides the Near Infrared Spectrograph, Mid-Infrared Instrument Optics Assembly, and the Ariane Launch Vehicle |

| Canadian Space Agency (CSA) | Provides the Fine Guidance Sensor/Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph |

As a rule, each technical center participates, either as manager or as a contributor, in many programs and projects and therefore has responsibilities to interface with many extended enterprises, as shown in Figure 5.1. For convenience, we refer to the collection of entities in all the extended enterprises that interact with a technical center as the center's “extended organization.” The technical center's extended organization includes not only entities in the extended enterprises with which the center interacts on program planning and execution but also entities within the TRIO enterprise administration that provide direction and administrative support to the center.

Figure 5.1 The extended organization for a NASA center

The success of such extended-organization endeavors depends on the establishment of communication protocols that promote consistency of approach across the entities, sharing of information while protecting that which is proprietary, and seamless integration of the products.

5.2.2 Relationship of Each Technical Center to the Other Entities in the Center's Extended Organization

In its multiple roles, each technical center within a TRIO enterprise acts as its own enterprise with its own set of objectives to be achieved, as an integrator of risk and opportunity information emanating from the other entities in the center's extended organization, and as an element of the extended enterprises charged with helping to ensure that the TRIO enterprise's strategic objectives are achieved.

These multiple roles are illustrated schematically in Figure 5.2, where NASA's strategic objectives are taken as an example of the executive-level objectives that each center supports. In this figure, the executive-level strategic objectives are divided into three types:

Figure 5.2 NASA example of how each center takes risk and opportunity inputs from a variety of entities and supports multiple strategic objectives of the agency

- Those that are principally programmatic in nature and are allocated to centers by the mission directorates (program directorates)

- Those that are more institutional in nature and are managed, by designation of the NASA administrator, within centers and within the Mission Support Directorate

- Those that are required of all agencies in the federal government and are typically managed at the executive (NASA administrative) level

Correspondingly, the objectives of each technical center within a TRIO enterprise can be divided into three types that mirror the categories that apply to the higher-level strategic objectives:

- Support of specific programs and projects that are assigned to the technical center in service of the TRIO enterprise's mission

- Provisions for additional institutional capabilities needed to maintain the technical center's core competencies

- Support of mandates that are required by the federal government or other sources

The risks, opportunities, and leading indicators associated with these types of objectives tend to cut across each technical center's extended organization. This cross-cutting aspect is illustrated in the lower part of Figure 5.2, which depicts the inputs from the center's extended organization that are needed to perform the roll-up, or aggregation, of risks and opportunities within the center. These risk and opportunity inputs are divided into the following categories:

- Individual risk scenarios, opportunity scenarios, and associated leading indicators that are unique to the technical center

- Individual risk scenarios, opportunity scenarios, and associated leading indicators that affect not only the technical center in question but also other entities in the center's extended organization

- Aggregate risks and opportunities for objectives that are unique to the technical center

- Aggregate risks and opportunities for objectives that emanate from or are shared with other entities in the center's extended organization

5.2.3 EROM Organizational Structure for a Technical Center's Extended Enterprises

Experience has shown that for EROM to be practiced successfully in enterprises that have multiple partners, there needs to be an EROM team for each extended enterprise that prepares the overall risk management plan and oversees the management of risk and opportunity (Holzer 2006). The team at the extended enterprise level is responsible for identifying risks that cross over the interfaces between entities (i.e., between technical centers, contractors, and other partners) and/or that emanate from those interfaces, for conducting preliminary analyses to assess the likelihoods and potential impacts, and for assigning primary ownership. When the origin of an interfacing or cross-cutting risk initiates from an action or inaction of a particular entity within the extended enterprise, ownership is typically assigned first to that entity. If the entity lacks authority to act on the risk, it is elevated to a higher level within the chain of authority. Frequently, risk ownership is assigned at program or project level if the process of resolving the risk requires action at that level. Thereafter, the EROM team monitors the resolution process, which may involve the improvement of existing internal controls, establishment of new internal controls, or formulation and implementation of a mitigation plan.

To flesh out and monitor interfacing and cross-cutting risks and opportunities, the EROM team may establish various subgroups. The number of subgroups or their particular names are not that important. What is important is that their responsibilities with respect to one another are clearly defined and the schedules under which they operate are coordinated.

For example, there may be separate working groups and management boards established for each organizational unit, for each program/project, and for each technical center, as shown in Figure 5.3. Risk and opportunity (R-O) working groups for each entity would have responsibility for identifying, analyzing, and recommending controls and mitigations to reduce risks pertaining to the entity's objectives in the extended enterprise. They would meet on a regular, scheduled basis with their corresponding R-O management board to share risks and opportunities that affect the entity and review decisions made by the management board about how to respond to them. They would also meet with the working groups of the other entities in the extended enterprise at regularly schedule meetings organized by the program/project, to discuss and evaluate risks and opportunities that are of mutual interest. Although not specifically shown in the figure, informal communications between the working groups of different entities could also occur between scheduled meetings when there is a need to discuss technical issues in an ad-hoc manner.

Figure 5.3 A representative EROM organizational chart for a technical center that manages extended enterprises

R-O management boards for each entity would have responsibility for prioritizing the risks and opportunities identified and reported by the entity's R-O working group, determining the kind of response needed, assigning ownership, monitoring progress, and approving changes of status. Typical responses for risks would include, for example, (1) accept and watch, (2) add controls, (3) mitigate, or (4) close-out. Changes of status would typically involve movement from one kind of response to another, and could involve elevating the response (e.g., from accept and watch to mitigate) or lowering the response (e.g., from accept and watch to close-out). They would also meet on a regularly scheduled basis with the management boards of the other entities at regularly scheduled meetings organized by the program/project to organize and adjudicate risks and opportunities that are of mutual interest.

The technical center, in addition to managing the extended enterprises that are assigned to it, has additional responsibilities that include contributing to other programs and projects, executing designated institutional initiatives to maintain its core competencies, and communicating with other technical centers that have similar responsibilities for other extended enterprises, with the program directorates that assign program/project responsibilities to the technical center, with the directorate that has institutional oversight at the executive level, and with the advisory councils and review boards that provide an evaluation function at the executive level. These interfaces are also shown in Figure 5.3.

The principal goal of the EROM structure, which cannot be overemphasized, is for all entities to be involved in the EROM process by having technical representation in a working group and/or managerial representation in a management board. This far-reaching intent is necessary to achieve the buy-in that is needed in all parts of the extended enterprise.

5.2.4 Challenges of Creating and Managing an Integrated Database

As discussed in Section 4.8.3, wherever there is a need for EROM oversight and communication between entities, there is also a need for an integrated database that incorporates EROM information across these entities. At the extended enterprise level, the integrated database should typically include the information in the risk and opportunity templates, the owner for each risk and opportunity, the organizational entities that are involved, corresponding working groups and management boards, change plans, change history, and status.

While ideally the integrated database for an extended enterprise should capture all risks and opportunities for all the participating entities, some entities may already have an established risk management process and database that they do not want to give up. To facilitate acceptance of the process, exceptions to the principle of a totally integrated database may have to be made. For example, some entities may need their own version of the database because they do not have network connectivity. Periodically (perhaps weekly), they might provide a copy of their database updates for uploading into the main database. Other entities may have concerns about proprietary information and not want to have all their data available to all participants. It may be decided that such entities may maintain their own separate database as long as they enter risks and opportunities into the main database that have the potential to degrade the capability performance at the program/project level. These entities would be aware of how their risk and opportunity data affect the extended enterprise by virtue of having access to the main database.

Because of the cross-cutting nature of enterprise risks and opportunities, there is also a need for reduced, summary databases that integrate EROM information at higher levels of the organization. For example, there should be a repository of data at the technical center level covering those aspects of EROM that cut across the extended enterprises within the center's extended organization. Similarly, there should be a data repository at executive level covering the aspects of EROM that cut across the technical centers, program directorates, support directorates, and management councils.

5.3 EROM-Informed Budgeting of Resources across a Technical Center's Extended Organization

5.3.1 Objectives-Based Distribution of Human, Physical, and Instructional Assets

An important function of EROM, in its institutional mode of operation, is to assist each technical center in the budgeting of key resources across the extended organization. The key resources to be budgeted, as shown in Figure 5.4, include human assets (personnel trained and experienced in different skill areas), physical assets (supporting facilities, IT systems, other systems, equipment, and software), and instructional assets (supporting policies, requirements, standards, and guidance documents). The budgeting involves more than costs. In addition to satisfying cost constraints, the final distribution of assets must reflect the intent of the TRIO enterprise's strategic objectives that are inherited by the technical center, including: successful execution of programs and projects that support the strategic objectives, maintenance of core competencies in specified strategic areas, promotion of strategic partnerships, and sharing with the public through strategic education initiatives. The tools for achieving this strategic distribution of assets are both quantitative and qualitative.

Figure 5.4 The success of a technical center's inherited strategic objectives is dependent on the “right-sizing” of the resources available to the center (NASA example)

5.3.2 Representative Templates for Distributions of Allocated Assets

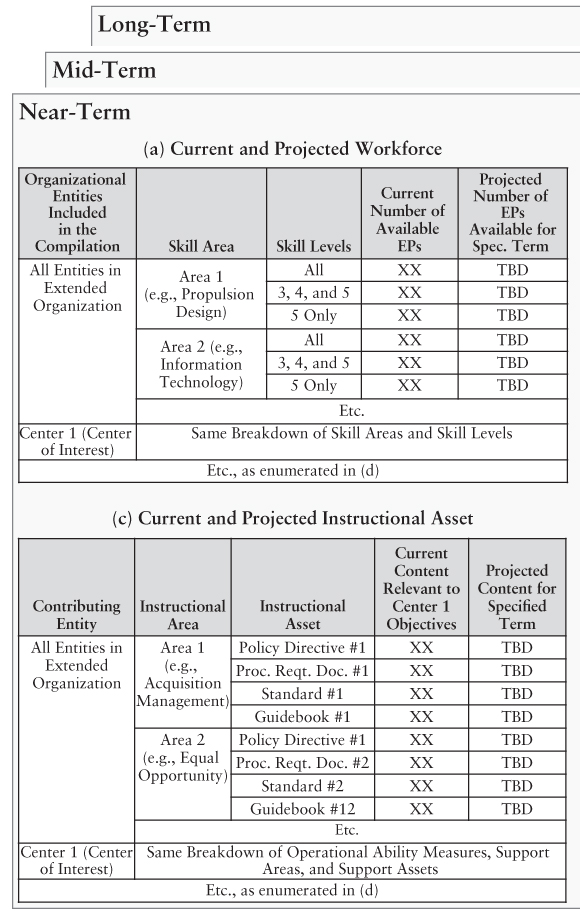

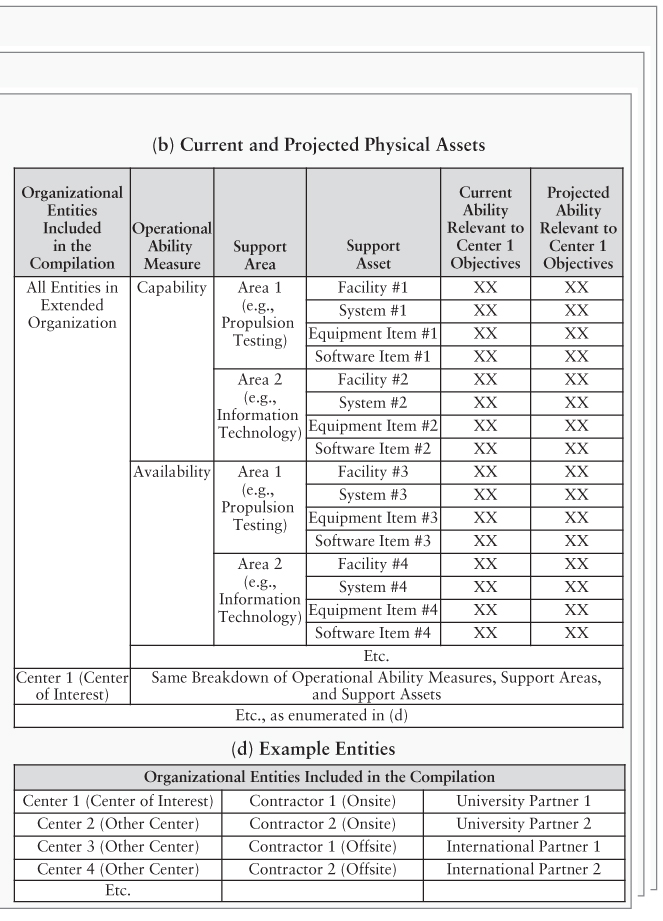

Representative templates that may be used for displaying the distribution of allocated assets are provided in Table 5.2. These templates include both current and projected distributions. The projected distributions refer to the predicted allocation of assets in the near term (∼1 year), mid-term (∼5 years), and long term (∼10 years), assuming the current plan is implemented. The specific entries in Table 5.2 are discussed in the following three subsections.

Table 5.2 Templates for Distribution of Human (Workforce), Physical, and Instructional Assets

|

|

Human Asset (Workforce) Distribution

The success of any organization (whether an entity in a technical center's extended organization or the extended organization itself) depends on the ability to hire and maintain a skilled workforce. Since several of the strategic objectives inherited by technical centers pertain to diversification of the workforce through formation of partnerships with other domestic agencies, commercial enterprises, universities, and international agencies, it is necessary for the proper skills to be maintained in all the contributing entities of the center's extended organization. The particular skills to be preserved have to be matched to the needs of the programs and projects that the technical center is managing or contributing to, as well as to the additional core competencies that the technical center is required to maintain.

Table 5.2 (a) illustrates conceptually the type of information needed to evaluate the status of the workforce across the technical center's extended organization. It includes the number of experienced personnel (EP) at different skill levels for each skill area that is needed and for each entity that contributes. Skill level designations on the scale of 1 to 5 can be interpreted, for example, as follows (typical of Industry standards):

Each combination of skill area, skill level, and contributing organizational entity is referred to herein as a workforce category.

Physical Asset Distribution

Because the strategic objectives of the TRIO enterprise include both enterprise objectives (programs and projects) and, in the case of federal agencies, national policy objectives (e.g., the well-being of the TRIO enterprise's commercial, educational, and international partners), it is necessary not only for workforce allocations to be considered in a holistic manner across the extended organization, but also for the distribution and utilization of physical assets to be so considered. As mentioned earlier, physical assets in the present context include supporting facilities (including test facilities), IT and other systems, equipment, and software.

Table 5.2 (b) illustrates conceptually the type of information needed to evaluate the status of physical assets across the technical center's extended organization. It includes the capability and availability of each asset to be used to satisfy the technical center's objectives, broken out according to the support area that it addresses and the entity that owns it.

The specifications of capability and availability in this template are expressed verbally rather than numerically (although numerical information may be included in the verbal descriptions). This is different from the specification of EPs in the allocation of human assets, which is strictly numerical. Both terms, capability and availability, are specifically referenced to needs for satisfying the technical center's objectives. For example, the capability of a propulsion test facility to test small components is not a relevant capability if its use for the technical center is only for testing of full-up systems. Likewise, the availability of a propulsion test facility for purposes other than those needed by the technical center and its extended organization are not relevant and do not need to be tracked. In a large sense, the description of the capability and availability of a physical asset is equivalent to a statement of its ability to meet the technical center's performance and availability requirements.

Instructional Asset Distribution

Since the TRIO enterprise's mission is dynamic and the means it uses to achieve its objectives change from time to time (e.g., as a result of the increasing complexity of its missions or the occurrence of breakthrough technology advancements), its instructional documents frequently need to be updated or superseded. Similarly, the instructional documents for entities that partner with the TRIO enterprise may need to be revised or superseded to be consistent with the TRIO enterprise's policies and requirements, and one of the TRIO enterprise's responsibilities will be to audit the contents of the partners' instructional documents. As noted earlier, instructional documents include policy directives, procedural requirements, standards, and guidance documents.

Table 5.2 (c) illustrates conceptually the information needed to characterize the status of instructional assets relevant to the center's operation and the operation of its partners. It includes the content required of instructional documents in various instructional areas over the near term, mid-term, and long term. Again, the content is expressed verbally rather than numerically, and only content relevant to the technical center's objectives need be entered in the template.

5.3.3 Asset Risks, Opportunities, and Risk/Opportunity Scenario Statements

In addition to the risks and opportunities associated with the successful performance of the technical center's designated programs and projects, there is a separate category of risks and opportunities associated with the center's human, physical, and instructional assets and its obligation to maintain its mandated core competencies. Both types of risk have to be considered in the overall assessment of whether a technical center is achieving all its objectives.

Risks of future asset shortages and imbalances can arise from various sources. Following, for example, is a list of risks that could affect the viability of the workforce by causing people to leave prematurely:

- If funding is cut or a program is retired earlier than expected, people might seek more stable work alternatives.

- If a program is extended beyond its planned time frame, the impact of retirements might become more important.

- If competition in-house for qualified persons increases, people might transfer to other organizations to increase their opportunities.

- If market competition for qualified persons increases, people might accept positions with other companies with higher pay.

- If local economic conditions degrade, people might move to another part of the country.

- If a contractor or partner develops financial problems, that entity might not be able to maintain its workforce.

- If people are required to work longer hours on a continuing basis, people might seek positions that are less stressful.

Other risks can affect the viability of the workforce by increasing the number of qualified persons that are needed to achieve the technical center's objectives beyond those that are available. For example:

- If domestic or international political priorities mandate an acceleration of the schedule or an increase in the scope of the objectives, there might be a need for more qualified people.

- If an important task in a project falls behind schedule because of unexpected difficulties, there might be a need for an increased allocation of people to that task to get it on schedule again.

There are also events that could lead to opportunities pertaining to the workforce. For example:

- If funding is increased due, for example, to favorable economic conditions, it may be possible to attract persons with unusually high qualifications by offering higher salaries or other monetary incentives.

- If market competition for qualified persons decreases, it may be possible to attract qualified persons without offering higher salaries or other monetary incentives.

Risks that could affect the viability of physical and instructional assets include the following:

- If a facility has to be shut down unexpectedly due to an accident, malfunction, or the mandate of a watchdog organization, its availability to the technical center may disappear.

- If another program that requires use of the facility suddenly gains high national priority, the availability of the facility for the technical center's use may decrease.

- If a catastrophic accident occurs in one of the TRIO enterprise's programs or projects, the TRIO enterprise's policies and procedural requirements may have to be changed to respond to findings of the ensuing review board.

- If a revolutionary new technology becomes available offering new opportunities previously not thought possible, the TRIO enterprise's standards and guidebooks may have to be rewritten to accommodate the new technology.

Obviously, the last of these encompasses both a risk and an opportunity, for while there is a risk that the instructional documents may have to be rewritten, leading to increased cost and/or schedule implications, there is simultaneously an opportunity for implementing improved technology.

For asset risks and opportunities, it is useful to expand on the risk and opportunity scenario statement structure presented in Section 3.4.2 to include information about the effect of the risk or opportunity on assets in the extended organization. Following is a specialized form of risk/opportunity scenario statement that satisfies the general format but is specifically applicable to risks and opportunities affecting assets in the technical center's extended organization:

This risk/opportunity scenario statement recognizes that there are several ways in which a departure event can affect the viability of the human, physical, and/or instructional assets for the technical center's extended organization. The event can result, for example, in a positive or negative change in:

- The number of experienced personnel available to the extended organization in various workforce categories

- The number of experienced personnel needed by the extended organization in various workforce categories to meet the technical center's objectives

- The availability and capability of physical assets under the purview of the extended organization

- The availability and capability of physical assets needed by the extended organization to meet the technical center's objectives

- The content of instructional assets needed by the extended organization to meet the technical center's objectives

These variants are encompassed in the risk/opportunity scenario statement within the phrase [envisaged or required] availability, capability, and/or content of specified human, physical, and/or instructional assets. Note that while each of the variants is different from the others, they all lead to a common result: an imbalance or gap (either positive or negative) between the assets in the extended organization and the assets needed to satisfy the technical center's objectives.

5.3.4 Leading Indicators of a Technical Center's Health

In addition to the leading indicators cited in Sections 3.4.4 and 3.4.5 and those listed in Table 3.1, there is a separate category of leading indicators associated with the technical center's ability to maintain its mandated core competencies. For example, the following is a subset of workforce-related leading indicators recommended for NASA use by the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) (Harper et al. 2007):

- Median age of workforce

- Number of uncovered full-time equivalents (FTEs)

- Ratio of fresh-out hires to total hires

- Ratios of civil service persons to contractors and supervisors to staff

- Center-by-center use of workforce incentives such as flexible work schedule, bonuses, and subsidized student loan payments

- Percentage of people participating in training over the past year

- Number of turnovers and absenteeism

- Overall productivity rating

- Employee perceptions/assessments of management (e.g., from 360-degree feedback and Best Places to Work survey)

- Number and severity of disciplinary actions

- Number of unfair labor practices and Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) complaints

- Ranking in Best Places to Work in the Federal Government, diversity element

These were devised by NAPA as being indicators of the health of a center, and in particular, indicators of the risk of not being able to maintain a robust workforce.

Similar lists can be postulated for physical assets and instructional assets. For example, the following list of attributes can be thought of as leading indicators of the health of a technical center with respect to the availability and capability of an organization's physical assets:

- Median age of facilities

- Maintenance history of facilities

- Scale factors for testing

- Unaddressed cybersecurity threats

- History of changes to policies and procedures

5.3.5 Correlations between Internal Leading Indicators and Gaps in the Distributions of Human, Physical, and Instructional Assets

Important correlations exist between leading indicators that were cited earlier, such as schedule and cost margins, and gaps in the distributions of human, physical, and instructional assets. These correlations make it possible to develop a risk- and opportunity-based plan for acquiring, allocating, and retiring a technical center's human, physical, and instructional assets.

To illustrate by way of example, suppose that there happens to be a shortage of skilled personnel available to the prime contractor for the JWST project in the area of cryogenics for cooling systems, and suppose that, based on current trends and expected future events, the shortage is projected to worsen during the next five years. When this information is factored into the scheduling for JWST development and testing, it may be found that the margin for the completion of the buildup of the integrated system is less than the trigger value for significant concern (i.e., the response trigger value as defined in Section 3.5.1). When this information is transferred to the risk roll-up template for JWST (Table 4.6), it may be found that there is an intolerable risk of not being able to satisfactorily achieve the following strategic objectives that the center is committed to:

- Objective 1.6: Discover how the universe works, explore how it began and evolved …

- Objective 3.1: Attract and advance a highly skilled, competent, and diverse workforce … needed to conduct NASA's missions

Observe in this example the following entry on the workforce template for the technical center's extended organization:

- Number of people in skill category 4 or 5 in the skill area of cryogenics working for the prime contractor

is directly related to the following leading indicator:

- Schedule margin for JWST integration

Thereby, it has been identified as causing two of the center's top objectives (listed above) as having an intolerable risk of not being satisfactorily achieved.

In addition, it should be apparent that the same sort of correlation can exist between entries on the physical and instructional asset template, the leading indicators pertaining to margins, and the technical center's top objectives. For example, if a certain testing facility is not available when needed or lacks certain needed capabilities, the schedule margin for completion of testing may be intolerably low, thereby having the same effect on the technical center's top objectives.

Likewise, the distributions of human, physical, and instructional assets can affect the ability to take advantage of opportunities that may arise in the future. For example, having a few skilled researchers available to conduct innovative research in a pioneering propulsion technology may lead to an opportunity to utilize that technology to expand the TRIO enterprise's objectives related to exploration of our solar system or to accomplish its current objectives more quickly or at less cost.

5.3.6 Optimization of the Acquisition, Allocation, and Retirement of Human, Physical, and Instructional Assets

Optimization of the plan for acquiring, allocating, and retiring human, physical, and instructional assets is an iterative process that utilizes the correlations between assets, leading indicators, and the technical center's objectives. The optimization process is summarized in Figure 5.5 and proceeds as follows:

Figure 5.5 Outline of the steps in the iterative process for optimizing asset distributions based on costs and current and projected values of leading indicators

- The technical center's objectives and associated risks, opportunities, and corresponding leading indicators are identified as in Chapter 4.

- An asset allocation plan that is postulated to meet cost constraints is proposed using the templates in Section 5.3.2.

- The effect of the allocation plan on the current and projected leading indicator values is evaluated based on the discussion in Section 5.3.5, using the Leading Indicator Evaluation Template (Table 4.3).

- The risks and opportunities are rolled up to the technical center's top-level performance objectives using the Risk and Opportunity Roll-Up Templates (Tables 4.6 and 4.9).

- The cost of implementation of the asset allocation is evaluated using traditional cost accounting methods.

- Modifications to the asset allocation plan are considered to determine whether the balance between overall risk and opportunity exposure and overall cost can be improved.

The iterative process may continue until any of the following conditions occurs:

- The overall risks to success cannot be further reduced within cost constraints.

- Additional significant opportunities cannot be availed within cost constraints.

- Costs cannot be reduced without significantly increasing the overall risk or sacrificing significant opportunities.

The iterative process is illustrated in more detail in Figure 5.6. As part of its graphical display, Figure 5.6 includes the Leading Indicator Evaluation Template originally presented in Table 4.3, modified to include not only performance risk indicators but also asset and UU risk indicators.

Figure 5.6 Illustration of iterative process for optimizing asset distributions based on costs and current and projected values of leading indicators

5.3.7 Relevance to Provider Acquisition Decisions Made by Technical Centers

The processes described earlier in Section 5.3 can be applied to assist the technical center in selecting providers such as prime contractors and other suppliers. The process of deciding between alternative providers is determined in large part by the amount of risk versus the amount of opportunity that each brings to the table in helping the technical center achieve its objectives. The steps that a technical center needs to implement in order to make a rational selection are similar to those described in the earlier subsections, but with a focus on the risks and opportunities that are brought by each provider. Very briefly, these steps are as follows:

- Identify the risk and opportunity scenarios that are introduced by allocating the selected tasks to the provider.

- Identify and evaluate the associated leading indicators.

- Integrate the risk, opportunity, and leading indicator information for the provider with the corresponding risk, opportunity, and leading indicator information that is already in the EROM templates.

- Perform the roll-up of risks and opportunities using the roll-up templates including the risks and opportunities introduced by the candidate provider.

- Determine which candidate provider maximizes the likelihood of the technical center being able to achieve its objectives.

The steps are similar to those in Figure 5.5, except that new risk and opportunities introduced by a new candidate provider are taken into account and the iterative process is not exercised.

References

- Harper, Sallyanne, et al. 2007. “NASA: Balancing a Multisector Workforce to Achieve a Healthy Organization.” A report by a panel of the National Academy of Public Administration (February). http://www.napawash.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/00-NASA-Report-2-20-07.pdf

- Holzer, T. H. July 2006. “Uniting Three Families of Risk Management—Complexity of Implementation x 3,” INCOSE International Symposium 16 (1): 324–336. Also available from National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). 2016c. “The James Webb Space Telescope Team.” http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/webb/team/index.html