CHAPTER 3

Investing as a Team (2003–2014)

2003: A NEW MANAGER

2003 ushered in another milestone. After 13 years of going it alone, the asset management team doubled in size. We went from being one asset manager to two.

To be fair, Mario Serna had been supporting me as an analyst for nearly two years, but he didn't have any prior experience and was still learning the ropes. Over the years, a number of analysts had done an excellent job for Bestinver Securities and the equity broker, but they focused on analysis for foreign clients who invested through the securities brokerage. I was involved in hiring some of them and even managed them at times, but they were all young graduates who helped me only intermittently and on specific issues, for example making the case for the valuation of Endesa and its subsidiaries. Their main job was supporting the broker rather than the asset manager.

I confess that I made a mistake with Mario, which I may have been guilty of in the past and later on too. I led by example, without setting aside time to specifically instruct him or apply a coherent approach. This might have been enough for some people – I think the young people who spent time on the asset management side had a satisfactory experience – but perhaps it was not for everyone. This might be why Mario decided to call it a day when Álvaro arrived. Fortunately, he turned out to be the only departure from the asset management analysis team over the next 10 years.

The decision to take on another fund manager was far from easy. I was after an established asset manager; somebody still young, but who already had some experience under their belt. And as I was used to making my own decisions, with a system that worked for the clients and myself, it was a challenge to transition to a more consensual approach. However, it was becoming a necessity to have support from somebody else – particularly in the international area – to help improve decision-making and reduce client risk.

The results so far had been excellent, but the losses in 2002 arose partly from having too many companies in the international portfolio, with a lack of complete control over multiple evolving scenarios. It was too much for one person to be on top of the details of the 150 companies in the portfolio, plus the 30–40 companies in the Spanish portfolio, and the hundreds of potential candidates under consideration (see the appendix at the end of this chapter).

In Spain there were around 100 possible investments on offer, which was feasible at the time after 13 years of accumulated experience. But we needed to apply the same processes we had used in Spain – where our error rate was extremely low – to the selection of global companies, making it an imperative to devote more resources to analysis in this area.

The decision to recruit Álvaro Guzmán de Lázaro was straightforward, as it has been for all our major appointments. He was introduced to me by a common friend and ex-analyst from Bestinver and Beta Capital, Antonio Velázquez-Gaztelu. They visited one day to discuss the virtues of Repsol and we met a couple of times afterwards for lunch. It soon became clear to me that Álvaro was a good fit for the job. I wasn't about to launch a routine recruitment process or such like. In fact, we never did for key positions. Álvaro started working with us in the spring of 2003.

He was the right fit for the company. He completely understood and shared our philosophy and he had experience applying a similar management style for a family portfolio. By day he worked as an ‘ordinary’ analyst at Banesto Bolsa, but at home he spent time on his passion – finding top-notch stocks for his own portfolio, which required a lot of personal effort and persistence.

Álvaro is a more typical example of how to start investing than I am. If no one is prepared to pay you to invest – which is logical for the young and inexperienced – then you have to go for it in your free time. The amounts invested are an irrelevance. Indeed, my case is even starker than Álvaro's, I started with just 50 shares in Banco Santander. The key thing is to learn the process, survive the emotional ups and downs, and build confidence in your ability to invest effectively and convey that confidence to others. Believing that we can invest and being able to prove it, even with small sums, is a crucial first step. Nowadays, the Internet offers the opportunity to self-teach, learning from and copying other investors.

One of Álvaro's major contributions was to standardise the models of the companies in which we invested. Something that I had not done. Up until then I had kept all the ideas in my head, believing that if anything slipped out then it was probably with good reason. This was more than likely not the best approach, but it seemed to work for me. Fortunately, the arrival of Álvaro – and other colleagues later on – meant that everything was fully documented on paper or digitally.

Collectively, we formed a team that worked well. We had few disagreements over the choice of stocks, and any differences were resolved ‘democratically’. I didn't think it was right to impose criteria on the team, so the decision to buy into a company had to be unanimous. We didn't invest if there wasn't consensus. Álvaro and I didn't always see eye to eye on certain macroeconomic issues, but these weren't pivotal for our type of investment. I think we only disagreed on two or three stocks, which strikes me as a good outcome.

His arrival meant we could travel to Europe more frequently to visit our companies and improve our knowledge of them. And gradually, the quality of our international fund improved. By the end of 2003, European stocks now accounted for 67% of the international portfolio.

The fund rose by 32.7% in 2003 (compared with an 8.83% increase in the index), enabling us to recuperate our 2002 losses.

BULL MARKET: BUBBLES

By the start of 2003, IBEX 35 stocks accounted for 20% of our Spanish portfolio. Three years of tumbling markets had opened up some tantalising opportunities, such as Repsol or Aguas de Barcelona, which embellished our usual suspects: Mapfre, CAF, Elecnor, etc.

But while the Spanish market was attractive, we were far from blind to the clouds that were gathering over the economy and that would go on to have a dramatic impact within a decade. As can be seen from an interview I gave to Javier Arce in the magazine Futuro (see below) in May 2003, the real-estate bubble was starting to seriously concern us.

‘For example, in the real-estate sector, we are seeing the creation of a bubble, which is going to do a lot of damage some time in the next five years… When the economy grows by 2 and real-estate lending by 20, a bubble is being inflated… We have a typical supply-side crisis resulting from interest rates which are too low for the economy… This is one of the reasons why we don’t have a single bank share’.1

We recommended steering clear of Spanish banks and real-estate companies, but the warning clearly went unheeded and the bubble continued unchecked for nearly a decade. Unfortunately, it crashed back down to earth years later. 2003 saw a continual increase in our assets under management, reaching 225 million euros in the Spanish funds and 47 million in the international fund by the end of the year.

We had finally earned the necessary confidence of potential investors after 10 years of hard work and results.

2004–2005: THE REAL-ESTATE BOOM IN FULL SWING

We had forewarned of the dangers of the housing market bubble in Spain. And in 2004, we had yet further evidence that the fundamentals underpinning Spanish economic growth were far from sound, based on lending rather than saving and productivity growth.

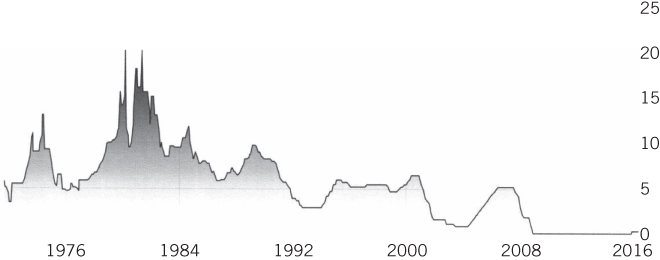

The European Central Bank, copying its American counterpart, had set short-term interest rates at 2% in 2003. This was too low for the needs of the Spanish economy, given that inflation was running above these levels. As can be seen on the following chart, Spain and Ireland, the two European countries with the biggest housing bubbles during that decade, were being offered negative real interest rates for three and four years, respectively. (The situation was not dissimilar in 2015 and 2016 but, fortunately, it was not transmitting to the economies in the same way, to the great bemusement of the central banks.) These negative interest rates provoked excessive lending growth.

Source: Macrobond & HSBC.

It was logical with funding at 2% and real-estate asset inflation of 10% that all economic agents wanted a piece of the ‘free for all’. Furthermore, banks were prepared to lend up to 100% of the investment, a rarity in normal times. This explains why there was so much overnight real-estate wealth: developers invested with third-party money, creating companies for each development. If it worked, they won; if it didn't work, they closed down the company with the losses going to the banks and on to the rest of the country. They never lost out.

Nor did the politicians or civil servants responsible for zoning the land. These individuals, whose decisions determined when and where construction would be carried out on each bit of land, and therefore who got rich from their decisions, were the true creators of unjust wealth – both for third parties and, frequently, for their own benefit. It's no surprise that Texas, which is the only place in the United States where construction is unrestricted, has the most accessible housing in the country in relation to wealth.

After several years of low interest rates, it was not until the last quarter of 2005 that rates finally began to rise in Europe.

The real-estate situation was of major concern to us, and we began to allocate the Spanish portfolio very conservatively, investing only in defensive and/or exporting companies. This would be a constant over the following seven years, until 2012. Furthermore, by December 2004, we had increased liquidity to almost 15% of the portfolio. This rose further to an average of 20% during 2005, the highest proportion since 1998. One of the biggest sales that year was Cevasa (a pioneer in the private development of state-subsidised housing for rental), one of our favourite stocks, with rental real-estate assets which had clearly been undervalued until that point. Our block of shares was bought by one of the many real-estate companies which later went to the wall.

GOING SHORT

As always, our warning of the bad times to come was premature, but at least we slept soundly. This is one of the advantages of never short-selling. Some readers will wonder why we didn't short the banks and real-estate companies if we were so convinced. If we consider the five years from 2003 until 2008 (in reality, the bubble in Spain held up surprisingly well during the global financial crisis and didn't burst until a bit later), a short position on these securities would have left us facing devastating losses, which would have put in question our very survival as investors.

A short is a bet that the price of an asset will fall. It can be done via derivative products, options, futures, and so on. We have never engaged in this type of investing:

- Because we are optimists, and we think that things will always improve. Humanity is living in a golden era and it will continue if people are left to work in peace. It doesn't fit with our personality or long-term objectives.

- Because time plays against investors with short positions, since quality real assets tend to gain in value. A good share, cheap and with potential, will increase in value over the years. It only requires patience for the market to wake up to it, and if it doesn't, we can increase our investment further still (or not, but we get to decide and the losses are limited to the investment made).

By contrast, time is against you when you have a short position. If the price of the asset goes up, you can face major losses, making it necessary to take on more guarantees and increased exposure to this risk, although the investor may not want to do so.

We have already mentioned that we were downbeat on the Spanish real-estate and banking sector over this period. If we had bet against the sector we would have suffered for nearly 10 years until those involved faced the music, and we might not have survived. Michel Lewis describes this agony to perfection in his book The Big Short.4

- Because short positions are exclusively short-term investments, and movements over this timeline are practically impossible to predict. Holding a short position in the long term is, technically, almost impossible.

In sum, we want to sleep soundly and we want the people who have placed their trust in us to sleep well too.

GLOBAL PORTFOLIO

By December 2004, European companies accounted for 80% of assets in the global portfolio. And we had reduced the number of companies from 150 to 100, focusing our investment on fewer stocks thanks to an increase in the quality of our analysis. Spain's excesses didn't seem to be so pronounced elsewhere and we found value, meaning we were fully invested.

Bestinver Internacional Portfolio (31/12/2004)

| STOCKS | Investment | % Total |

| TESORO DE ESPAÑA | 11,001 | 4.98 |

| TOTAL PUR. ASSETS | 11,001 | 4.98 |

| TOTAL FIXED INCOME | 11,001 | 4.98 |

| TOTAL DOMESTIC PORTFOLIO | 11,001 | 4.98 |

| Abrazas Petro | 923 | 0.42 |

| Amer Nat Ins | 2,098 | 0.95 |

| Ares | 643 | 0.29 |

| Avis Europe | 1,676 | 0.76 |

| Bally Tot Fit | 804 | 0.36 |

| Banque Privée Edmond | 0 | 0.00 |

| Barry callebaut | 2,912 | 1.32 |

| Batenburg | 517 | 0.23 |

| BE Semiconductor | 641 | 0.29 |

| Bell Holding AG | 885 | 0.40 |

| Bell Industries | 902 | 0.41 |

| Bilfinger | 0 | 0.00 |

| STOCKS | Investment | % Total |

| Boewe Systec AG | 2,515 | 1.14 |

| Bonduelle | 719 | 0.33 |

| Brantano NV | 2,835 | 1.28 |

| Bucherindstr | 5,869 | 2.66 |

| Buhrman | 7,768 | 3.52 |

| C&C Group | 925 | 0.42 |

| Camaieu SA | 6,782 | 3.07 |

| Carrere Group | 1,311 | 0.59 |

| Compass Group | 1,281 | 0.58 |

| CSM NV | 0 | 0.00 |

| D Ieteren SA | 487 | 0.22 |

| Dalet | 143 | 0.06 |

| DassaultAviat | 3,063 | 1.39 |

| De Telegraaf | 1,511 | 0.68 |

| Delhaize | 0 | 0.00 |

| Dentressangle | 1,196 | 0.54 |

| Devro plc | 951 | 0.43 |

| Dolmen Computer | 1,051 | 0.48 |

| Econocom | 4,870 | 2.20 |

| Edel Music | 841 | 0.38 |

| Engineering | 1,062 | 0.48 |

| Escada AG | 7,937 | 3.59 |

| Esprinet | 4,101 | 1.86 |

| Etam Develop | 2,955 | 1.34 |

| Fairchild Corp | 315 | 0.14 |

| Fairfax Finci | 4,730 | 2.14 |

| Faiveley SA | 2,463 | 1.11 |

| Finlay Enter | 2,369 | 1.07 |

| Fleury Michon | 899 | 0.41 |

| Fuchs Petrolub | 1,078 | 0.49 |

| GFI informatique | 1,290 | 0.58 |

| GIFI SA | 3,340 | 1.51 |

| Guerbet SA | 1,173 | 0.53 |

| STOCKS | Investment | % Total |

| Hagemeyer | 3,467 | 1.57 |

| Head | 767 | 0.35 |

| Heineken Hld | 1,215 | 0.55 |

| IDT Corp | 1,098 | 0.50 |

| Imtech NV | 819 | 0.37 |

| ISS A/S | 459 | 0.21 |

| Kanaden Corp | 862 | 0.39 |

| Kindy SA | 1,096 | 0.50 |

| Kinepolis | 6,908 | 3.13 |

| Kone | 0 | 0.00 |

| KonniklijkeAhold | 2,112 | 0.96 |

| Konniklijke Boskalis | 0 | 0.00 |

| Lafuma | 1,105 | 0.50 |

| Lambert dur Chan | 1,324 | 0.60 |

| Macintosh NV | 6,114 | 2.77 |

| Maisons Fra Conf | 809 | 0.37 |

| MarionnaudParfm | 2,947 | 1.33 |

| Matalan | 0 | 0.00 |

| Medion | 2,162 | 0.98 |

| Metallwaren Hldg | 6,319 | 2.86 |

| Metsa Serla | 1,294 | 0.59 |

| MGI Confer SA | 1,055 | 0.48 |

| M-RealOY3 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Nipponkoa | 1,968 | 0.89 |

| Nutreco NV | 6,314 | 2.86 |

| OCE NV | 6,681 | 3.02 |

| Okumura CORP | 0 | 0.00 |

| OPG Groep NV | 5,687 | 2.57 |

| Orchestra-Kazib | 882 | 0.40 |

| Panana Group | 1,049 | 0.47 |

| Passat | 1,696 | 0.77 |

| Pierre Vacances | 935 | 0.42 |

| Pinkcroccade | 0 | 0.00 |

| STOCKS | Investment | % Total |

| Playboy | 0 | 0.00 |

| Regent Inns plc | 1,645 | 0.74 |

| Rentokil | 0 | 0.00 |

| REpower Systems | 1,484 | 0.67 |

| Rite Aid | 5,168 | 2.34 |

| Roto Smeets Boer | 5,624 | 2.55 |

| Roularta | 2,137 | 0.97 |

| Sabate SA | 863 | 0.39 |

| Sasa Industrie | 1,303 | 0.59 |

| Shire Pharmaceuticals | 1,308 | 0.59 |

| Signaux Girod | 904 | 0.41 |

| Sligro Food Grp | 1,737 | 0.79 |

| Smoby | 1,405 | 0.64 |

| Stef Tfe | 348 | 0.16 |

| Sthn Egy Homes | 1,820 | 0.82 |

| Tommy Hilfiger | 1,275 | 0.58 |

| Tonnellerie | 2,038 | 0.92 |

| Trigano SA | 0 | 0.00 |

| Unilever | 951 | 0.43 |

| United Services | 2,535 | 1.15 |

| Varsity Group | 2,355 | 1.07 |

| Vet Affaires | 4,297 | 1.94 |

| Vetropack | 3,501 | 1.58 |

| VM Materiaux | 1,203 | 0.54 |

| VNU N.V. | 928 | 0.42 |

| WamerChílcott | 0 | 0.00 |

| Wegener | 7,212 | 3.26 |

| Wolters Kluwer | 0 | 0.00 |

| Zapf Creation AG | 962 | 0.44 |

| TOTAL EQUITIES | 209,978 | 95.02 |

| TOTAL EXTERNAL PORTFOLIO | 209,978 | 95.02 |

| TOTAL PORTFOLIO (thousands of euros) | 220,979 | 100.00 |

Source: CNMV.

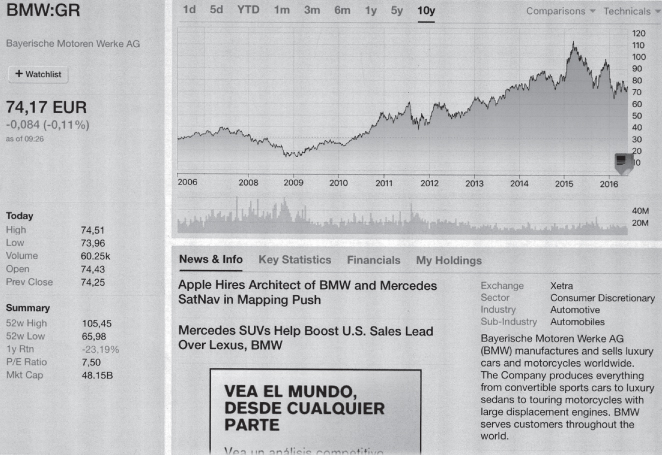

However, in contrast to the Spanish portfolio, we were still reticent about increasing the concentration in certain stocks in our global portfolio. For example, in the fourth quarter of 2004, only five stocks accounted for more than 3% of the total: Camaieu, Kinepolis, Wegener, Escada, and Burhman. As a side note, in June 2005 we bought our first position in BMW, which – after many ups and downs – has proven to be an exceptional investment over time.

We focused mainly on European mid-caps, which proved to be pretty rewarding, despite some clear duds such as Escada itself, Boewe Systec, Smoby, Schlott, Regent Inns, Alexon, Clinton Cards, and some others whose names are painful to remember. In all of them we lost practically our entire investment. However, these failures helped to improve our investment over the long term, because rarely do you fail to draw some useful conclusions for the future. It's preferable to reach such conclusions reading about others' experiences – it's probably essential and reduces the likelihood that one of our errors will be fatal – but making our own errors is inevitable and even to some extent desirable, to avoid dropping our guard, keep learning, and stay alert.

Despite these problems, the results during these two years were very positive – 19% and 30% – and outperformed the benchmark indexes. As can be seen, it's possible to obtain very acceptable returns despite suffering a few setbacks, and there are probably two keys to this: getting it right more often than not, and being very careful about the scale of errors.

We usually got it right, the 30 or 40 serious errors that we made accounted for 10% of our investments out of a total investment in 500 companies over time. That's a tolerable percentage.

The size of positions should follow Eugenio D'Ors' maxim: ‘Experiments should be made with lemonade and not champagne’. The stocks with the highest weight, over 5%, should command our total confidence to avoid the risk of serious damage. The riskiest bets should be kept to a prudent size, never more than 1–2%.

2006–2007: ON THE BRINK..

2006 was the last year of an undisputed bull market. In Spain we started with 20% liquidity, but we took advantage of market retrenchment in the second quarter to up our investment, which brought liquidity down to 10%.

During this second quarter, we bought Telefónica shares for the first time in 10 years. Post-correction it was now trading at a tasty price and we continued buying throughout the year, reaching 8% of assets in the Spanish portfolio by December, something we had never done before. The country meanwhile remained captivated by the real-estate dream, which was covertly absorbing the financial and political system.

It was another vintage year for the international portfolio, +24% while being invested up to the legally permitted maximum and with BMW now among the top three holdings, together with Fuchs Petrolub and Metall Zug. A good trio of aces.

However, the most scarring event of 2006 had nothing to do with investing. On 7 March, four of us from Bestinver plus two pilots were involved in an aircraft accident in Pamplona. As incredible as it may sound, it was the only time in 25 years that we used a private aircraft to travel. One Bestinver colleague, Alfredo Muñoz, director of finance and operations, and one of the pilots died. María Caputto, deputy sales director, Ignacio Pedrosa, sales director, the second pilot, and myself survived.

Despite the enormous emotional shock, it only had a small impact on the company's investment. With Álvaro in place we already had the necessary support to ensure continuity and our portfolio was always geared to investing in the long term, meaning I was able to spend a while coming to terms with what had happened. In reality, I wasn't out of action for long and within about two weeks I was able to start reading. My injuries were not significant and I received the full support of everyone, including José Manual Entrecanales and the entire Acciona group.

The advantage of enforced time out of the office was that I had no option but to start using remote IT tools. Little by little I began to adapt to the new emerging technologies, including the iPad, which I now struggle to escape.

In 2006 we reached the high point in terms of the continual and massive inflows of clients prior to the 2008–2009 crisis, hitting six billion euros in assets under management. This meant that our assets had increased by 20 in three years. It was absolutely extraordinary, giving us a 40% market share in the mutual fund sector reports registered on Inverco, the grouping of mutual funds for Spanish markets.

We had never been growth focused, but working without specific targets we had managed to attract more interest than we could possibly have imagined. Over the years we had two commercial or client relations directors, Ignacio Pedrosa and Beltrán Parages, neither of whom were ever assigned growth targets. We didn't get involved in any active promotional activity, with next to no advertising (except for a small campaign in 2000, Crisis? What crisis?, highlighting this year's good results), nor did we have any distribution agreements (except for some very small-scale ones which dated back to before 2000 and were maintained as a token of gratitude for confidence in us when we weren't well known).

There are various reasons why we adopted this passive approach. Firstly, when a client makes an active decision to come to us it creates a much stronger bond of trust, as it is a conscious decision made in the absence of pressure. This builds in some resilience during difficult times. Secondly, growth creates the need to set limits on the amount managed, so what business logic is there for sharing profitability within limited capacity with distributors? None whatsoever. Thirdly, we have frankly been fortunate to find ourselves in a position of not needing to do so. Under other circumstances, perhaps we would have taken a different decision.

Either way, we were caught off guard by the pace of growth and it wasn't until much later that we were able to get on top of the situation and provide a good service. Initially we lacked the physical space to respond to all the indications of interest, leading to inevitable backlogs and delays. It wasn't until we were able to double our capacity, expanding to another floor, that we got the situation under control.

2007

With the wind in our sails, we confronted 2007, a transition year following sustained positive performance. As we saw in the 1990s, the transition from a bull to a bear market tends to be one of the more challenging for us because our portfolio, which is geared to being conservative, fares less well in the dying throes of a bull market.

Fortunately, we started the year by taking on a third fund manager, Fernando Bernad. Once again it was a straightforward hire. He was introduced to us by Álvaro, who had worked directly with him at two different times. He was a great help to us from day one, thanks to his extensive prior experience in our type of management. In fact, he had even been responsible for a small asset manager, Vetusta, which was no longer in existence. His arrival enabled us to expand the analytical team, taking advantage of his ability to manage and organise them. Álvaro and I lacked the time, and perhaps the desire, to manage and coordinate the work of a large team of people. We had clear ideas about where we added value and we wanted to avoid upsetting our working conditions.

Every decision to strengthen the team is a hard one. Each new person increases capacity and adds value, but they are also an added restriction, given that we have to set aside time to train them. You end up losing a degree of freedom, and sometimes the role of asset manager gets confused with people manager. Therefore, we have always selected learned fund managers, such as Álvaro and Fernando. It's a different story for analysts, where we have always picked academic high flyers with limited experience, so we can train them as we see fit. This approach wouldn't have been possible without Fernando, who played a key role in their training, putting together a sound team that – over time – was able to contribute good ideas.

From this point on we hired Carmen Pérez Báguena and Mingkun Chan, who joined Ivan Chvedine, who was already working for us as an analyst. Collectively we formed the sextet which was forced into pitting its wits against the crisis.

At the start of the year, in March, I sent a letter of thanks to Warren Buffett. I made the decision in Tenerife when I discovered that he had bought shares in Posco, the Korean steel company. We had recently been involved in Arcelor and I liked the parallel. In the letter I thanked him for being a source of inspiration to me, an investor stranded in a country like Spain, with little investment tradition. I also suggested that he buy BMW preference shares.

He replied almost immediately, two days later, asking for ideas about investing in Spanish private companies. Not a single company came to mind that would fit with his philosophy, so I didn't respond. This, unfortunately, ended our short-lived correspondence.

Another key milestone took place in the spring, when I joined a week-long seminar organised by IESE in China. I was already positively inclined to the country, remembering Jim Rogers' superb books. As a retired asset manager he had travelled the world, first by motorbike and then by car, carrying out an ‘on the ground’ comparative analysis of the various countries he visited. His main conclusion was that China held the key to the future, which he justified with the following arguments: the Chinese people's fervour for improving their living standards; their capacity for work and saving; and reasonable protection of property rights, with less bureaucracy and corruption than similar developing countries.

It was with great interest then that we visited Chinese companies, subsidiaries of foreign companies, investors, and academics. I also separately arranged to visit the China offices of the companies in our funds. It was a unique experience, which deepened my understanding of the country's economic development and decision-making process. I began to read avidly a wide variety of books on China, ranging from fiction to academic and journalistic non-fiction. Particular highlights were The Second Chinese Revolution by former Spanish ambassador to China, Eugenio Bregolat,5 and, especially, Peter Hessler's Country Driving,6 which provided an enlightening description of the daily life of Chinese people.

Over the years, and following various trips, including a family visit with summer camp included, I discovered for myself that China's development was substantive and based on a capacity for work and saving which allowed them to overcome any obstacle put in their path. The image of an economy that was supposedly under the remote control of the Communist Party was far from the reality. A whole spectrum of activity was completely free from government interference, providing a degree of flexibility unknown to Europe, Japan, Brazil, and other developing countries. This freedom, combined with very significant competition in non-strategic sectors, allowed for strong growth without inflation. And even in economic areas which were effectively controlled by the Party – electricity, transport, basic resources, etc. – the Chinese enjoyed what the legendary President of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, described as the best bureaucracy in the world, thanks to an essentially meritocratic system.

What's more, up until 2009, this development was not based on debt. That is, until the global crisis forced a relaxation of monetary rules. Years later the debt level is now elevated, but the assets underpinning it are real and substantive. I don't deny that there may have been some bad investments in infrastructure, but the essence of China's development remains the population's enormous capacity to adapt to a changing and highly competitive environment.

That said, we didn't start investing in China, but we still thought it was essential to be well informed about the country. This led to the hiring of Mingkun Chan, who we signed from IESE. It was not an easy choice, given the quality of the field: 17 all-Chinese candidates. The other finalist had won a debating tournament… on Japanese TV!

Africa Support Fund (euros)

| Country | Total (country) |

| Angola | 202,000,00 |

| Benin | 73,427,00 |

| Burkina Faso | 7,200,00 |

| Burundi | 58,500,00 |

| Cameroon | 130,000,00 |

| Congo Brazzaville | 5,350,00 |

| Eritrea | 110,000,00 |

| Ethiopia | 64,000,00 |

| Kenya | 106,500,00 |

| Mali | 28,850,00 |

| Malawi | 699,076,00 |

| Niger | 5,000,00 |

| Mozambique | 24,540,00 |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | 44,300,00 |

| Tanzania | 684,013,50 |

| Sierra Leone | 139,041,00 |

| Sudan | 411,660,00 |

| Uganda | 527,107,29 |

| Zambia | 35,000,00 |

| Total (year) | 3,355,564,79 |

Source: Africa Direct.

Back to the markets. The first half of 2007 started well enough, but problems began to emerge in the summer in some structured products (using derivatives: options, futures, etc.) backed by real-estate mortgages, signalling that a change of cycle was in the air. We have almost always steered clear of structured products (the only exceptions being bonds indexed to commodities and Japan in 1998 and the 2000 Nasdaq bond). They are hard to understand and you feel as though you are being charged hidden fees, which makes them less attractive.

The likely result therefore tends to be somewhat similar to inflation and little more. Likewise, we have hardly ever invested directly in derivatives, options, and futures. These instruments shift the investment focus to the short term (long-term hedges are excessively expensive, although cheap in the short run) and we believe that short-term movements are totally random. The best hedge for a portfolio is to construct it with sound stocks at a fair price.

I say ‘hardly ever’ because during 2000–2001, as a one off, we did try to cover our dollar investment. At the time, more than 30% of the assets in the global portfolio were in dollars, with the dollar trading at its highest level for 30 years, below one against the euro. After hedging against a possible dollar depreciation for a couple of quarters, the regulator, CNMV, got in touch to remind us that as we didn't have a ‘risk control unit’ we couldn't keep going with this hedge. We gave some thought to creating such a unit, but decided against it, given the cost and the limited occasions on which it made sense to use derivatives.

We have always maintained an excellent relationship with the regulator, but that time they were wide of the mark. We complied with the letter of the law, but it cost our clients a loss to the tune of 10% of their assets when, in subsequent years, the dollar depreciated by 40% to reach 1.35 against the euro in 2005.

Returning to 2007, while we were clear about the (grim) prospects ahead for Spain, having set out a very defensive portfolio – in fact, we had broadened our sights to Portugal to try to limit the exposure to Spain – we were not as well prepared for a global crisis, despite having no explicit exposure to the financial sector. We were not as alive to the American real-estate boom and its implications. We didn't know how to apply the same perspective we were applying to Spain to places such as Miami or Las Vegas.

Meanwhile, we sincerely believed, and were later proven right, that our portfolios were robust – with good companies and reasonable prices. We have been asked many times why we didn't prepare for the fall by holding more liquidity, but in reality we were content with our global portfolio. There was no problem with our companies, but rather with other highly overindebted companies which provoked a temporary liquidity freeze that indiscriminately dragged down the whole financial system.

Our most significant investments in that period went on to perform superbly over time, both in terms of results and share prices. Only Alapis and Cir/Cofide turned out to be disappointments. The first because of fraud, which ended up with the incarceration of their chairman (take away: don't invest in companies that invite you to all their events and where the chairman travels with a legion of bodyguards); the second because of the catastrophic situation of the European electricity sector in recent years.

The second half of 2007 was already proving difficult; our funds posted negative returns, both in absolute terms and in relation to the market.

We've said it before and it's been illustrated several times in this account: the worst time for us is a change of market from bull to bear. The type of companies we invest in at these times are defensive, and we typically hold above normal liquidity. This time our liquidity was at normal levels, but we were coming off the back of an exceptional run of performances by our funds, which led us to drop our guard a little and be less vigilant than we should have been.

Out of curiosity, in autumn 2007, I tagged along to the Investor Day of one of the big Spanish banks just to see how the banking sector was bearing up. I was able to confirm their complete ignorance about the state of play in the housing market. I discovered that they had absolutely no idea of what was about to hit them. The commercial director brazenly forecast that 500,000 to 600,000 homes would be built per annum over the next five years.

If one of Spain's largest banks didn't have a clue about what was going on, it only confirmed my overall impression that the financial sector was going to be badly affected, particularly the cajas (or savings banks). The high degree of political interference was a particular problem for the latter, and rumours were continually circulating about fraudulent lending activity and attempts to cover up the scale of the problem. When people talk about nationalising the banks to avoid a repeat of the past, they show gobsmacking myopia about what happened to the cajas, which were controlled by the regional political establishment, yet again demonstrating how political intervention is an aggravation in a financial crisis.

We ended the year with one of the most significant developments for a long time regarding our product range: we set up a hedge fund in the autumn, which was essentially a concentrated fund. It was designed to be the crème de la crème, reflecting our best ideas, capable of outperforming the other funds but subject to somewhat greater volatility. Time has shown this to be the case, with the hedge fund obtaining some additional percentage points of return over Bestinfond.

After initially starting out with a fee schedule that was similar to the competition, we changed the fees for the hedge fund because we thought it was unfairly punitive on the client, creating an innovative new system. The fixed fee was identical to the fund reflecting our model portfolio, Bestinfond, and any excess returns obtained by the hedge fund over this fund were split 50–50 between the client and the asset manager, a highly satisfactory solution for all parties.

2008: THE BIG FALL

Despite being very well prepared in the Spanish portfolio and not having invested in financial companies in the global portfolio, the first quarter of 2008 got off to an exceptionally bad start, registering declines of 6% and 12% in the NAVs of the Spanish and the global portfolios, respectively. This happened despite receiving three purchase offers in the global portfolio, notably for Corporate Express, an important company for us with a weight of 3.5%. It was a bad omen for the rest of the year.

However, the main problem during the quarter was not so much the results the funds were posting, but the outflow of investor money. Funnily enough, the bulk of our outflows took place at this time and not after the Lehman Brothers collapse in September. And this was because many of the overwhelming number of investors who had arrived in previous years were clearly not prepared to endure stock-market volatility. In fact, there were numerous cases of people buying funds using bank loans, which were also being given away lightly for non-real-estate-sector activity too. Thus, the bulk of the year's redemptions, which ultimately amounted to 20% of assets, took place in that first quarter.

Redemptions during those three months were running at around 20–30 million euros a day, but we were able to handle them without major issues with the help of the purchase offers we'd received, the offloading of some significant blocks of shares, and investments from our shareholders, who took advantage of attractive market prices to carry out investment in the funds.

LIQUIDITY

Some people have accused us of obtaining good results through exposure to illiquid stocks. As we have seen, this was not always the case, with extended periods of investment in large caps – in reality we're agnostic about company size, we are solely interested in their business and valuation. However, the supposed problem of a lack of liquidity in secondary stocks is a non-sequitur. The crucial problem which can make life difficult is getting the valuation wrong. When you get it right and the share is trading at a discount, there is always going to be a counterparty. Sometimes you have to offer a small discount, say 5%, but on other occasions you obtain a higher price than the market. Illiquidity trading (being prepared to buy a share that has little trading volume and wait patiently for the market to price it correctly) is one of the most simple and reliable options around.

By contrast, the supposed liquidity in large-company stock can evaporate from one day to the next. We suffered an example of this with Ahold a few years earlier. We valued the company at 13 euros and seeing as it was trading at nine euros, we thought it was an attractive proposition as a member of the EuroStoxx 50, the index of large European companies. The issue was that the accounts didn't reflect the reality and when this was uncovered, the share price opened the next day at three euros. So a large and liquid company lost 66% of its value overnight and, needless to say, there was no liquidity either at nine euros. Our error was in the valuation.

What grated with us was that in this particular case there had been some warning signs – as almost always happens – which should have alerted us. In particular, their decision to buy a chain of Spanish supermarkets, Superdiplo, where we also had a stake and considered that Ahold had overpaid. But there's no room to hold a grudge in investment and years later we bought back into Ahold, with a degree of success.

Meanwhile, the list of small companies which we sold at their target price is endless: Cevasa, Inmobiliaria Asturiana, Fiponsa, Tudor, Grupo Anaya, Fuchs Petrolub, Camaieu, Hagemeyer, Buhrman, etc. In some cases the market itself woke up to the underpricing and brought them up to a fair price; in other cases another company bought them outright; there can be a multitude of possible drivers, but they all help to eliminate this inefficiency. The biggest exception we faced was the previously mentioned sale of Endesa's subsidiaries. The latter very shrewdly made use of a merger process which required an exchange to take place if an ‘independent’ evaluator gave the green light to the exchange equation, as proved to be the case. If they had launched a share purchase, we wouldn't have participated. This happened with Camaieu, the French clothing distributor, where we only consented to the third buyout, which took place two years after the first attempt. Anyway, we didn't lose money on Endesa's subsidiaries, we simply missed out on lost earnings.

The latest and most recent example of the false liquidity problem took place when I left Bestinver, followed by my colleagues in 2014. 25% of assets were redeemed in a quarter, but they were able to sell the necessary shares on a bear market without having to resort to discounts, except on a handful of occasions.

2008: CONTINUATION

Returning to 2008, the second quarter saw the two portfolios lose another 6%. While the Spanish portfolio fell less sharply than the index in the first half of the year, the loss in value was broadly similar in the global portfolio. The markets afforded some respite in April and May, with strong recoveries of around 20%, following JP Morgan's decision to purchase the insolvent Bear Sterns, one of Wall Street's leading investment banks.

Redemptions continued but the pace slowed significantly relative to the first quarter, which – together with the recovery in the market facilitating necessary sales – went a long way to steadying our nerves. Strangely enough, throughout the whole year building work was taking place in the office and the entire team was working in the same room, instead of our normal offices. I suppose this also helped us to hang in there.

In the global portfolio we reinvested in Ciba part of the sales from the share purchases. It was a global leader specialised in chemistry and went on to reward us with a welcome surprise not long after. Buffett had bought Rohm & Haas in the summer, a chemical company with similar characteristics to Ciba, at a much higher price than Ciba's multiples.

To add fire to the flames on the financial problems in the United States, rising commodity prices and especially oil – which stood at 140 dollars a barrel – led to a spike in global inflation expectations. Oil, which 10 years before had been trading below 10 dollars a barrel, had multiplied by 15 over the decade, while the stock markets had not done much at all, with a return of around 0%. You could already sense where the value would be in the future.

Our funds dropped sharply again in the third quarter, with the Spanish portfolio shedding 12% and the global portfolio 9%. After a relatively calm summer, September unleashed the biggest economic turmoil in recent decades. Lehman Brothers collapsed on 15 September, followed days later by serious problems at AIG, Merryll Lynch, etc.

THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

The general feeling among public opinion is that the financial crisis was caused by malicious Wall Street bankers, whose greed broke the idyllic social order created by a healthy and diligent society. They undoubtedly have their share of the blame, but blaming them is like pinning drug problems on the guy pushing on the street. We all know that those who are ultimately – or principally – responsible are the big traffickers who put the drugs on the market in the first place, and the consumer, while the dealer pays for the harm caused by their own weakness. In the case of the financial crisis, the people ultimately responsible were those who artificially lowered interest rates or bent legal obligations, providing access to lending to people failing to meet the necessary minimum conditions.

In Spain, we were clean of the Wall Street virus and the CDOs (mortgage ‘chunks’), all of which is brilliantly explained in The Big Short; yet, we had the same problems, if not worse than the Americans. What we did have in common with them was the interest rate.

The underlying problem is that the price of money (the interest rate) is not determined by the market, as happens with clothing or food; instead it is decided by so-called state experts on the basis of limited information (we will go into this in more detail in Chapter 4). What would we think if the price of clothes was decided by a panel of experts? It's happened in some countries and we know the outcome.

Returning to interest rates, how could a policy of artificially low interest rates not create perverse effects? Clearly somebody was going to try to make the most of it, and the Wall Street operators were in a privileged position to use the means on offer to them by the political class, in this case the Federal Reserve.

These low interest rates, which were also the driver of the Spanish crisis, dated back to 1998, when LTCM was bailed out for fear of being ‘too big to fail’. After that there was the dot.com crash, the 9/11 attacks. and the second Iraq war, giving the Fed plenty of excuses to keep base rates below 2% for the three years from 2002 to 2005. In spring 2003 short-term interest rates stood at 1%, the lowest since 1958, against a backdrop of over 2% inflation. In other words, negative real interest rates for three years. Accordingly, in a period of two years from 2004 to 2005, house prices in the top 10 American cities rose by 38%, according to the Case–Schiller index.

Source: Federal Reserve.

But it wasn't just the Fed who were to blame, the US Congress also played a part. (If the problem had been limited to low rates, perhaps the crisis might have been avoided. From 2008 to 2015, interest rates have been close to 0% without apparent harm; it appears as though the money has not trickled into the system in the same way as before.) It's incredible looking back at some of quotes from Barney Frank, the Democrat congressman in 2003 then responsible for the policy on Government-Sponsored Enterprise (GSE), Fannie Mae, and Freddy Mac, the financial institutions responsible for guaranteeing mortgages: ‘I do think I do not want the same kind of focus on safety and soundness that we have in the OCC (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) and the OTS (Office of Thrift Supervision). I want to roll the dice a little bit more in this situation toward subsidized housing’.7

Frank was not so much worried about the solidity of the system as driving up home ownership among the least well off, which is why he didn't let up on his efforts to oblige banks to follow his ethos, without worrying about people's repayment capacity. Previously, in 1992, the GSE had been subject to the affordable housing law, which required that 30% of guaranteed mortgages be provided to underprivileged households. This proportion rose to 50% under Clinton in 2000 and to 55% with Bush in 2007. As a result, a significant proportion of subprime or low-quality mortgages were guaranteed by quasi-governmental organisations controlled by the US Congress (according to the SEC).

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was also important. This was old legislation from the President Carter years, which was strengthened by the Clinton administration and which required non-discrimination against minorities in the provision of loans, effectively obliging banks to grant them. In this regard, the words of another politician are enlightening, Andrew Cuomo, US Secretary of Housing under Bill Clinton, in regard to the judicial decision requiring banks to grant mortgages to the less well off: ‘The bank will take on more risk with these mortgages… it will give mortgages to families who wouldn’t otherwise have been able to access them… Lending amounts to 2.1 trillion dollars in high-risk mortgages and I'm convinced there will be higher incidence of default on these mortgages than on other loans' (in Thomas Woods, Meltdown8). And he slept easily after saying it. On investigation, the GSEs guaranteed 1.7 trillion dollars of high-risk mortgages.9

Simply put, in the 15 years leading up to the crisis, Congress and the American executive actively promoted house buying among the underprivileged. A laudable objective if it had been done prudently, without surpassing desirable limits, but that's not how it went down.

The global financial crisis would not have happened if two of North America's leading political institutions had refrained from interfering in monetary price formation (via interest rates) and mortgage lending conditions (through legislation encouraging people with low repayment capacity to take on debt).

In this context, some of the American commercial banks, Wall Street – people who, by the way, have little to do with our way of working – and the ratings agencies responded overly aggressively, as they are inclined to do when taking advantage of any loophole liable to generate fees, issuing confusing and opaque products. This was enhanced by an incentive system which favoured short-term asymmetric ‘bets’ of the type where, if the trader gets it wrong, it's the institution they work for that takes the hit, but if they get it right, they stand to make significant personal gains.

China also played a role in pushing down interest rates through major purchases of American bonds.

These factors compounded the problem that had been created, taking it to an extreme. But neither Wall Street banks nor the Chinese governance can be held primarily responsible for something that took place elsewhere and for which they were solely accomplices to the previously mentioned political institutions.

Who did and didn't see the crisis coming? While Barney Frank and the rest of the pro-intervention political and academic establishment championed lending to people with doubtful repayment capacity, there were some exceptions. An example is the libertarian congressman Ron Paul who at, the same time, on 10 September 2003, told Congress that:

The credit line to the GSEs… distorts the allocation of capital. Even more importantly, the credit line is a promise made in the Government's name to carry out a large-scale, immoral and unconstitutional income transfer from American workers to GSE debt holders.

Ironically, by transferring the risks of generalised mortgage losses, the Government is increasing the probability of a painful real estate crash.

Despite the long-term damage inflicted on the economy by Government intervention in the housing market… in the short-term it is generating a boom… which will not last forever.

I suppose being a doctor helped Ron Paul to have a clear perspective on things. Meanwhile, one of the most influential living economists, Nobel Prize winner Joseph Stiglitz, issued a report in 2002 on the GSEs. In this report, prepared with Jonathan and Peter Orszag, he concluded that with new capital standards the risk of severe shock was less than one in 500,000.10 Another Nobel Prize winner, Paul Krugman, also of the interventionist bent, was still claiming in 2008 that the GSEs had nothing to do with the real-estate crisis.

CIBA: SALVATION AT THE DARKEST HOUR

By enormous coincidence, the same day that Lehman Brothers announced its bankruptcy, 15 September 2008, we received a purchase offer for Ciba, the second largest position in our global portfolio, accounting for 8%. Basf, the German chemical company, was seizing the moment to buy assets at a good price. Ciba shares had been trading at 25 Swiss francs in the summer, rising to above 30 on the back of rumours, which was formalised on the 15th with an offer of 50 francs. We valued the company at around 100 francs (Basf's own advisors, in the document accompanying the purchase offer, estimated the company's value at 80–87 francs in their fairness opinion), and initially turned down the offer.11

After waiting several weeks, and observing the market collapse, in November we decided to sell our entire stake to Basf. Since Ciba had gone up in value by 75% and the rest of the portfolio had fallen by 25%, it now represented 20% of our portfolio. This entailed a degree of risk, and offloading the shares would provide us with some liquidity firepower at an ideal time. The alternatives had now become extremely attractive, making it increasingly less appealing to hold on to Ciba shares and fight for a higher price. The ability to detach oneself from building emotional connections with investments is a major asset; it's better neither to become besotted with a specific stock or company, nor to despise them either. We must be able to adapt to different circumstances. Despite the potential for a further 100% increase in the price of Ciba shares, we decided to offload our holdings, giving us the opportunity to buy companies with potential for 200% upside. The extra liquidity would also give us a cushion to withstand a worsening of the crisis.

This is yet another example of the importance of focusing on stock picking over attempting to predict what will happen in the world. We live under constant uncertainty and will continue to do so until the only sure thing in life comes knocking. I remember listening to these happy words for the first time when I started working in the financial markets in 1990, and I haven't stopped hearing them since. Want to guess what moment we are in right now? You got it – a time of great uncertainty.

Despite tumbling prices, by October 2008 our investors were no longer withdrawing much money. Our investors are a sensible bunch, and we were already talking about falls of over 25% from 1 January, such that the desire to sell began to dissipate. Throughout the year we went to great lengths to communicate and be transparent. We held telephone conferences, we started publishing the target values for our funds, and we broadened the information set out in our quarterly reports and other client communications.

On 30 September we sent another letter to clients, along similar lines to that of December 2000. In this new letter we stressed that our portfolios were extremely conservative and that the American housing market adjustment was now quite well advanced. The letter, and other efforts to communicate, appeared to have the desired effect.

Madrid, 30 September 2008

Dear investor,

Recent events have had a significant impact on various financial institutions in Western Europe and especially the United States. The crisis has the same origins as its predecessors: an over-leveraging of the financial system endorsed with the tacit or explicit support of the corresponding authorities. As we have been warning for some time now, such excesses always come unstuck, to the detriment of nearly all concerned.

However, we would like to reiterate that while in the short term it may seem as though Bestinver funds have been affected by the situation, the long-term impact will be minimal, providing us with an opportunity to take advantage of the turmoil. This is due to several factors:

- Our exposure to the banking sector has been non-existent for some time now and will continue that way, this is no coincidence, but rather a prediction of the credit bubble bursting.

- Over 90% of our companies have minimal debt or none at all. They don't need credit to operate; some of them have net positive cash.

- Customers of our companies are dispersed around the world, meaning they can focus sales efforts on more attractive markets (China, Brazil, Germany, etc.).

- We should not lose sight of the fact that global growth in 2008 will be around 3%. It could slow in 2009 but remain positive, given the strong stimulus to growth from Continental China, which is based on sustainable factors such as savings and productive work, both of which have been in short supply in some western countries. Despite the steady flow of negative news coming out of the western world, various other countries are growing sustainably, without accumulating debt.

- The extreme surge in commodity prices, which has had such a negative impact on some of the companies in our funds, is starting to revert. This will provide a very significant boost to Western consumers, which will soon be reflected in their purchasing power.

- As we noted back in January, the biggest negative impact on our funds is coming from the lack of liquidity affecting some co-investors in our companies. This will be short-lived and will ultimately reveal the enormous value in our investments. We are publishing target values each month on our website and they have been on a steady upward path since the start of the crisis.

The end of the ‘crisis’ is unlikely to come until house prices stop falling in the USA. In some areas, price declines have reached around 50%, meaning the end may well be in sight. The North American economy's major asset is its impressive flexibility. An incredible adjustment has taken place in less than 18 months which will provide a much more solid base for the years to come. We sincerely believe that the long-term effects will be positive.

Either way, we remain convinced – however surprising it may seem – that equities are the best asset for preserving value at a time of financial crisis. Patience and composure will enable us to reap the rewards in the medium term.

In October, we will expand on all these points in our quarterly letter, which forms part of our commitment to explaining our work to the best of our abilities.

Francisco García Paramés

Chief Investment Officer

Transparency has always been an essential part of our relationship with clients. It's true that there have to be some limits – the competition is always peering over our shoulder – but within these limits we try to be as helpful as possible. This enables our clients to better understand our work, which helps us.

As a consequence, over the crisis as a whole, from summer 2007 to spring 2009, redemptions amounted to a little over 20% of assets under management. This was primarily due to institutions pulling out, as they have a harder time withstanding outside pressure than families.

In the last quarter of 2008, not only did the crisis fail to let up, but it worsened, and the falls were even more pronounced: 15.7% on the Spanish portfolio and 20.9% on the global fund! Our overall losses came to 35.16% and 44.71%, respectively. 5% better than the market on the Spanish fund and 5% worse at the global level.

October was particularly painful. We posted losses of 15%, but there were days of 10% price falls, followed by short-lived rebounds. As it happened, my third daughter was born on 9 October, in the midst of the worst days.

Her arrival helped put the crisis firmly into perspective, easing the tension around us and creating some distance from what was going on. The continued declines had created a surreal sensation, almost as if it was all a big wind-up. Álvaro brought the latest positions to the hospital and we tried to make the most of the movements in share prices.

By the end of 2008 the Spanish portfolio was trading at a P/E ratio of six and the global portfolio was at 3.4. These were obviously the lowest prices we had ever encountered, and wouldn't be repeated for a long time. The potential upside was enormous, 150% and 340%, respectively.

2009: IMMEDIATE RECOVERY

2009 started in a similar vein to the end of 2008, with more losses which continued into the first week of March. But some positive signals were already beginning to emerge, and with the change of year I gave serious consideration to borrowing to invest; the first time I had thought about it in 18 years. Any investment, even more so with equities, should be made with surplus savings, money that's not needed for daily life. Debt should be a small component of any investment. It's true that a housing investment could be underpinned by a mortgage worth 50% of the value of the asset – at most – but investment in equities should involve very modest amounts of debt, never more than 15–20% of the value of the shares. We should be able to sleep at night if we cap debt at these proportions, knowing we will be able to withstand market movements.

I don't invest using debt, except for the one instance when I first started out investing; however, 2009 seemed like too good an opportunity to miss. In the end, I couldn't make up my mind.

The clearest indication that we were at the low point came from my own inner circle. For the first time my wife queried whether her mother's modest investment in the funds, whose returns helped cover her expenses, might not be better placed in a less volatile fund. This took place in February in our kitchen at home, and I distinctly remember thinking that if even my wife – who had been and is a firm believer in what we do – was wavering, then the end of the crisis could not be far off.

As it happened, the low point of the crisis coincided with our Investor Days. Barcelona on Thursday, 5 March and Madrid on Monday, 9 March – the same day the markets hit rock bottom. We are talking about prices which hadn't been seen since 1996, 13 years earlier. On 9 March, the S&P 500 was trading at 57% below the peak of a year and a half before. The second largest crash in history after 1929.

When we arrived in Barcelona, the international fund's NAV was at nine euros per share, down 62% on a high of 23.6 euros in July 2007 – just 18 months earlier. Never in my worst nightmares did I think a portfolio managed by us would suffer losses of 25–30% in value, let alone 62%... We didn't quite know how our clients were going to react. We had done a good job explaining our approach over the years, and we had redoubled our efforts in 2008, but we were talking about enormous losses.

We gave an extremely exhaustive presentation, going into more detail than ever and disaggregating the portfolio to a level of granularity rarely seen in the market. For example, we spoke of our two biggest investments: BMW, which was being given away at 11 euros (it's now trading at 70 euros) and Ferrovial, trading at three euros (it's now priced at 20 euros).

Source: Bloomberg.

Source: Bloomberg.

As always, we made sure to handle all the audience's questions and the response was overwhelming: not only were they understanding and interested, but they applauded at the end of the conference. We were applauded. This might well be the most extraordinary thing to have happened to me in all my years as an investor. People who had seen 60% of their savings wiped out (only temporarily, mind you, as we insisted) applauding the people ‘responsible’ for these losses. Three days later the applause was repeated in Madrid, and this surprising show of confidence gave us renewed strength to continue fighting the falls.

But the rot stopped that same day, on 9 March. It's worth pausing a moment to talk about the viability of the company and ourselves as managers, something I also gave consideration to at the suggestion of my wife. In 2009 we were managing two billion euros, a massive drop from 6.5 billion in July 2007. We never took on debt and were always backed up by Acciona, meaning that we faced the crisis from a healthy position. We made a quick calculation and believed we could endure additional market falls of 75–80% before the company's future was in jeopardy. In other words, we could go from 6.5 billion euros in assets to 500 million and still maintain the same investment approach and team. This was an additional source of comfort.

Maintaining a break-even or a low earnings threshold, both professionally and personally, is a key trait for being able to survive independently and remain resilient. It was surprising to learn that some of our competitors folded, citing insufficient funds, when they were still managing hundreds of thousands of euros or dollars. In some cases it covered up a semi-fraud; closures can happen because managers are paid success fees and the losses would have prevented them from collecting for a long while. But in other cases the foundations of the company were plain shaky, failing to give consideration to a worst-case scenario and its implications.

The professional resilience of a robust company should also be accompanied by an extremely low threshold of family or personal outgoings, enabling us to overcome a variety of circumstances in our private life. We should always be prepared to be calm in the face of hardship; neither excessive debt nor a lavish lifestyle are compatible with our style of management. Both my wife and I have always been acutely aware of this.

I sincerely believe that the approach to investing and living need to be congruent.

But at the time what really calmed our nerves was the rapid recovery in the markets from 9 March onwards. In March, various stocks which had taken a major kicking – such as Debenhams, Esprinet, Oce, etc. – rebounded by 80–170%. In some of these companies we had increased our positions thanks to the leverage generated from Ciba, and we were particularly satisfied to see that many of the revivals came after the companies published good results. Which is how it should be.

By the second quarter the results were through the roof. 21% for the Spanish portfolio and 43% on the global side. The recovery in the global portfolio was the strongest we'd posted in a quarter, and it was followed by continued increases in the second half of the year. Bestinver's NAV, which touched bottom at nine euros in March, ended the year at 18, a 100% increase on our nadir and up 71% on the start of the year.

THE QUALITY OF COMPANIES

One of the accusations that could be laid at our door is that, despite foreseeing the excesses of the financial system, we didn't set aside enough liquidity to deal with the consequences. However, the reality is that we liked our companies and believed they would stand up to any situation. It's worth reiterating that, although for our taste some sectors might be overvalued or at potential risk, if we believe the portfolio is in good shape then the best approach is to wait until the storm abates.

However, in hindsight it was clear that the quality of companies in our global portfolio was not as good as it ideally should have been in order to withstand a crisis. Our Spanish portfolio was formed of a very good selection of defensive stocks and exporters, embodied by Ferrovial, which represented 9%. But this wasn't true of the global portfolio, where in some cases we were still too focused on price at the expense of quality.

Indeed, the crisis confirmed that high-quality companies at reasonable prices perform better over the long term than companies which are straight cheap. It's a path that takes us from Graham, specialist in companies with very underpriced real assets, to Buffett, focused on higher-quality stock, proxied by the degree of competitive advantage they enjoy.

Many investors have gone down this path, practically all the value investors. The main reason is that it delivers better results over the long term, although there aren't many studies to back up this assertion, making it initially a far from obvious conclusion. Added to this, when we are young and start out investing, we have an excessive desire to do well and make our mark, meaning we tend to favour the cheapest companies, which on face value offer the greatest potential upside. As we mature, after having stepped on a few booby and/or value traps (cheap companies in bad businesses, which languish for years, failing to create value) and our economic situation improves, our tastes tend to shift towards quality, even if you have to pay a bit more for it.

We will discuss the road to quality in more detail later on, but for now I will just mention that my catalyst for going down this route was a small book by Joel Greenblatt, The Little Book That Beats the Market,12 which provides statistical confirmation that quality is worthwhile. After reflecting on our own portfolio – which was of moderate quality – and given our desire for greater resilience in the future, we began to move more deliberately down this path. This meant that in 2009, certain stocks such as Schindler (old friend), Wolters Kluwer (another old friend), and Thales made it (back) into our portfolio, going on to amply reward us. On the flipside, as they began regaining value, we partially or totally offloaded stocks such as Debenhams, Smurfit Kappa, CIR (partially), and Alapis.

The natural implication of making this shift to quality, and our growing confidence in our stock selection, was an increase in the concentration of our global portfolio. By this time, we had around 60–70 stocks in our portfolio, which is where it remained.

2010–2012: EUROPEAN AND SPANISH CRISIS

Surprisingly, the global financial crisis didn't have an immediate impact on European economies, as the initial assumption was that the European financial system was more robust than the American one. But in 2010, with Greece already in the cross-hairs, the market began to fret about Europe, particularly the so-called periphery countries, which included Spain. Aside from Spain, like everyone else we were caught off guard by what had been happening in the periphery, including Portugal.

In Spain, time slipped by with the government engaged in a mindless Keynesian policy, spending money that the country couldn't afford. Meanwhile, the financial system was entering a palliative stage, hitting crisis point in 2012. Up until then, Spanish banks were still managing to hide their problems, extending and pretending bad loans while everyone around them turned a blind eye. It was in nobody's interest to tell the truth, neither the financial system, nor the political class, nor the real-estate sector, nor the people who had taken out loans knowing they wouldn't be able to pay. The Bank of Spain's experts knew what was going on but were silenced by the bank's political leadership.

It's worth remembering that in Spain the worst atrocities were committed in the cajas, ‘not for profit’ savings banks controlled by regional political powers. It wasn't greedy capitalists. It was once again the political class protecting their individual interests. Only when they were no longer able to pay the salaries of real-estate workers and bankers were they left with no option but to come clean.

The European crisis began in Greece in the spring of 2010 and exploded once and for all in summer 2011, setting the markets tumbling until summer 2012. Over many years, a number of European countries – chiefly Spain, Greece, Portugal, and Ireland – had lived beyond their means, generating large external imbalances which were covered by significant foreign financial inflows. In Spain and Ireland the investments had focused on the real-estate sector, which contributed next to nothing to increasing productivity and wealth. History was repeating what had happened in Asia a decade earlier.

When it became obvious that this type of growth wasn't sustainable, the external funding dried up and it was revealed that the Emperor was indeed naked. Injections of public spending did nothing more than worsen the problem, slapping a sticking plaster over it until 2012, when there was no other option but to face up to reality, particularly in Spain, the largest of the peripheral economies.

We had been anticipating this would happen for some time. And so, in the three years from 2010 to 2012, our Iberian portfolio went up slightly in value, while the Spanish index retreated another 30%. For the second time in 10 years we had managed to avoid significant losses on Spanish equities (though it was unavoidable in 2008).

Our portfolio of defensive and/or exporter stocks fulfilled its purpose perfectly during this tumultuous period and, eventually, we found ourselves in a new era in which bad news came flooding to the front pages of the newspapers, meeting the necessary conditions for us to invest in Spain. In 2012, 10 years down the road, we began to buy purely ‘Spanish’ stocks such as Antena 3, Mediaset (Tele 5), and Catalana Occidente, observing that the crisis was beginning to be reflected in the prices, which had fallen well below global and even European markets. However, it wasn't until 2013 that the first Spanish banks returned to our portfolio after 15 years of abstinence – in the form of Bankia and Bankinter. We didn't take part in Bankia's initial flotation in July 2011, but we did get involved in the post-rescue return in 2013. We liked the new governing board, the management team, and the high level of provisioning they had demanded before accepting the challenge of taking the bank forward.

2011 brought about a change of government in Spain. Initially the impact was limited. Despite having an absolute majority in Parliament, the centre-right PP party wasn't bold enough to act decisively. However, the continued deterioration of the situation and outside (mainly German) pressure forced them to be more determined:

- The critical state of the financial sector was recognised with support from European organisations. This created the conditions for the real-estate sector to gradually find a real market price for its assets.

- State spending was frozen. It wasn't dramatically reduced, but at least it was a change of stance compared with the past.

- A labour market reform was introduced to add flexibility to the relationship between employers and employees, enabling companies to better adjust to changing market conditions.

Overall, this brutal crisis, caused by living beyond our means for too long, brought about a certain change of mindset among my countrymen. The priority was no longer finding a cushy position as a local government official in a place close to home; this was no longer possible. You now had to go on the hunt for work wherever it could be found, even in faraway countries.

The result of all this is that I now sincerely believe that Spain has a unique opportunity to capitalise on its resources and make a leap forward in its global positioning. With world-class infrastructure (telecommunications, transport, hospitality, etc.), a privileged geographical location bridging three continents, and a degree of restraint in labour and real-estate costs, it's an attractive proposition for global entrepreneurs with ambitions to create new businesses or build on what they have.

There is no denying that Spain still has its fair share of problems, such as corruption or finding a fit for regional governments within a more viable and austere state structure, but they are not so serious as to detract from the advantages. I don't consider myself a rampant patriot, but I'm fond of my country and would like my countrymen to have a good future. I am making my own small contribution by returning to Spain, creating a company along with a good group of professionals, giving a service to clients who like our way of working, and contributing as best I can to promote my city and country.

Seen from today's vantage point, our biggest error at this point in the crisis was failing to have greater conviction in these purely Spanish stocks. Having waited for so long and got the timing right, we weren't decisive enough, only investing around 10% of the Iberian portfolio. I couldn't convince Álvaro, who had begun to develop a very negative view of the markets, and I didn't want to push him into it.

The European crisis also had some repercussions on the global portfolio, but they were modest. We only suffered significant losses in summer 2011, thereafter gradually recovering them. All of our top picks, to which we added Exor – the holding company for the Agnelli family – performed well, especially our beloved BMW.

2013–2014: OVER AND OUT

In 2013 my wife and I took the decision to spend two years in London. It was purely family oriented. We wanted to have the experience of living outside of Spain and exposing our children to an English-language education. We had spent the previous two summers in China and the United States, and new technology made it possible to work effectively from anywhere in the world. At least as a fund manager.

Plus, London is not just any old place. It's Europe's financial centre (or at least it was before Brexit), and it therefore gave us the opportunity to investigate whether it was worth setting up an office there to complement our work in Madrid.

It all seemed straightforward enough. However, some problems surfaced in Acciona in relation to my move to London. After mulling it over in summer 2013, I decided that in our type of business, which is almost a craft, being a manager must mean being able to manage the company and not just investments. Once the decision was taken, I tried to find a reasonable accommodation within Bestinver and Acciona, I owed them as much for the understanding and unconditional support I had received over 25 years.

We contemplated various options: taking a stake in the control of the company; diluting the decision-making power of the parent by involving a third partner; parting ways on a friendly basis; and some others. The process was extremely slow, as logically the other party wasn't much interested in changing the status quo, and after 15 months without finding any common ground, tiredness and frustration got the better of me and I announced my departure.

Throughout the entire process my goal was to ensure that clients had a smooth transition, giving them the option to make their own choice. But it didn't work out that way: my departure was abruptly announced and I shoulder much of the blame for this. I thought I would be back working again, one way or another, in no time and that my departure wouldn't be a problem, but I was wrong. I consulted on the interpretation of my contract with five legal advisors, four of whom advised me to work and the fifth recommended I wait out the two years indicated by the contract. I was ultimately convinced by the fifth lawyer, Valeriano Hernández-Tavera, who advised me not to compete but instead patiently sit out my two years. And this – for better or worse – is what I did; it fitted my character and strong aversion to confrontation.