CHAPTER 1

A Bit About My Early Years

I will start at the beginning, resisting the temptation to spare my own blushes. I feel it would not be natural to share my experience as an investor without first revealing a little about myself. There won't be any major surprises, but I think it is the natural order of things. I feel this is the way to do it.

ORIGINS

I grew up in an average and pretty normal family. My father was a naval engineer, a civil servant. He retired as Director of Maritime Industries in the Ministry of Industry, after having confronted the once famous ‘naval restructuring’ of the 1980s and being Professor of Projects in the Naval Engineering School. My mother was a housewife, mother of five children and an excellent cook. I cannot clearly recall them wanting to impart great life lessons to me; perhaps they tried, but I proved not at all receptive and confounded their best intentions. My introverted personality inhibited such ‘important’ conversations.

Even so, when I look at how I approach life, with the benefit of time, I do see some important traits that I inherited from them. For example, I have this inexplicable belief in the need to do the right thing. My father ‘did the right thing’ regardless of the circumstances and, without a shadow of a doubt, I share the same conviction. Likewise, these days I find the need to pass on my mother's folk wisdom to my own children, even though I used to laugh about it. Clearly this comes from them, whether genetically or by imitating their behaviour, which was always exemplary. Either way, they live on in me.

My childhood studies were normal. I always passed on time, with the exception of the university entrance exams, which I passed at the second time of trying. My grades were never exceptional because, except for occasional periods, no particular topic appealed to me. Gym was the class that I liked the most during this period, meanwhile physics was always totally incomprehensible. Recently I had another go, reading Richard Feynman, Physics Nobel Prize winner, but with no success.

Perhaps my aversion to physics was a premonition. One of the gravest errors of a cross-section of economic theory – as we will see – is applying natural science techniques, specifically physics, to social sciences, including economics, treating human behaviour as if it were an equation to be solved.

Overall, mine was a childhood without upheaval or apparent trauma, and not a hint of a financial whizz-kid, wheeling and dealing with my classmates. Nothing remarkable, like any other life.

However, when I turned 16 I developed a love of reading, which has gone on to become a core personality trait and a key constant in my life. Nowadays, when I see my 13-year-old son compulsively reading 500-page books, it surprises me how little I read at that age. Until 16 I didn't read books, because it wasn't part of my lifestyle, although I did at least read my father's newspaper nearly every day, and this helped me to stay informed about what was going on in the world.

In terms of global issues, I was especially interested in the existence of the Berlin Wall, which prevented people from leaving their country. I was astonished that people were prepared to die to change sides of the wall. It was then that I started to understand how freely organised markets are more effective at satisfying the needs of the masses, including the worse off. I sensed that what was happening on the other side of the wall was not pleasant, and it was incomprehensible to me how the intellectual world was not more critical of the wall and all it stood for in the face of such clear evidence. Later on I understood why; Aron, von Mises, and other thinkers cleared it up for me.

I became hooked on reading through the son of one of my father's friends. One night he spoke to me about how books represented a limitless world where it was possible to discover all that we were not seeing in our own placid lives. As a shy boy, rather introverted and something of a loner, it didn't require much effort to allow myself to be sucked into all types of stories. And from these conversations I was left with a name that will never leave my head: Proust. My friend had been a fan since the age of 14; I started a bit later.

This passion for reading is not particularly unusual in the so-called intellectual world of theatre, cinema or journalism, for example, but in the investment world it is a distinguishing feature compared with the average professional. The ability to gain exposure to an endless collection of people and stories, both real and imagined, fosters an open-mindedness that enables us to delve into the interests and preoccupations not just of these characters, but of the people in our own circle. Proust is an example of this, with his ability to dedicate various numbers of pages to the slightest perception of a secondary character or the etymological analysis of a name that attracts him. This came to be essential in my work.

During this period I read fiction, especially the great Spanish and French classics: Galdós, Cervantes, the generation of 1898, Stendhal, Victor Hugo, and countless other authors. Literature was the cornerstone of my reading. Later on, I gradually drifted away from fiction towards non-fiction, which has absorbed me during the bulk of my professional life. As a matter of fact, my non-fiction reading is very varied, with apparently little direct relation to my work: history, psychology, sociology, political science, etc. As we will see later, some of these topics have left an imprint on my personal and professional development.

As we have just noted, and will repeat later on, the right approach to the study of economics and investments is the study of man, which means that both novels and varied non-fiction are a good basis for building your own world view.

UNIVERSITY

Lacking a clear idea of what to do, I embarked on a course in Economics and Business Science at the Complutense University of Madrid. At 17 years of age I was pretty clueless, like most people at that age, and the best thing I could do was delay the important decisions for as long as possible. I did what I think is sensible in such cases: embarking on a diverse degree covering law, history, mathematics, accounting, business management, etc. A hotchpotch which could help me get my ideas straight and wouldn't close off any paths, except perhaps a career in building paths and bridges…

I went to a not especially prestigious public university and I did so for several reasons: failing the first round of university entrance exams, which took place in June, meant that I had little time over the summer to think about the future; and as I didn't have a clear idea, it didn't seem logical to force my family to foot any excessive costs. I also didn't believe that attending a private university was essential for a professional career. In reality, I thought of university studies as a formality that I had to get through, and I used part of the time available to learn languages – English, French, and German – again mostly in public language schools.

There is not much to highlight from the five years I spent studying at the Complutense University of Madrid because, evidently, it didn't clear much up for me. Whilst it didn't help me, at least it did plant the seed for what would later develop into my interest in the business world. More about that in a moment.

The first four years passed by inconspicuously enough. I combined my studies with language learning and military service, which proved very useful in getting to know the reality of my country, Spain. In my group of 10 sailors who shared a room together, there were two people who were illiterate, and only four of us out of the squad of 100 who had a university education. It is true that this was the Navy in Andalusia in 1984, but it also helped change my perspective on the world in which I was living, bursting my own little bubble. My country was no longer just my friends and my family; there was a wider world of people living very different lives from ours.

At the same time, I gave some consideration to trying to enter the diplomatic service. I didn't have a particular patriotic or political calling, but I found appealing the combination of exotic travel and, once again, the very wide variety of topics at the entrance exam. As can be seen, I have had a tendency throughout my life to try to leave as many options open as possible, and this is something I would undoubtedly recommend. However, in this case, I quickly abandoned the idea.

In the final year of my degree, something unexpected happened. It was a complete accident, arising from my love of sport, particularly basketball. On my visits to the library I had an enlightening encounter with a business magazine, which is no longer in existence. This encounter had great significance, both in 1985 itself – when the event took place – and later on in the future. The magazine was Business Week, and what caught my eye was the front cover, which featured no less than one Patrick Ewing, the star of university basketball and recent signing to the New York Knicks. Back then I found basketball, and especially the American professional league, NBA, a lot more inspiring than economics and business science, even though in those days we couldn't follow the games on Spanish television and had to make do with mythical photos.

The article explained the economic implications of Ewing's signing for the Knicks, which was probably the biggest up to that point in sporting history. But I also took the opportunity to read the whole magazine, which I found very engaging. Thanks to that, little by little, I began to gain an interest in the business world, which Business Week explained in quite an entertaining way. I cannot be sure whether this was a mere accident or the logical consequence of my passion for reading, but the truth is that this interest never went away. Up until then my focus had been on fiction, but gradually I started to take a greater interest in non-fiction, which I began to combine with literature. This seems to be quite a typical pattern, even taking it to the extreme where I only read non-fiction for years, thinking that literature – despite all I have said above – was not as worthwhile. These days I am more relaxed and have come to appreciate it again.

The truth is that it is important to try and look where others are not looking, and go beyond the superficial and commonplace. Doing otherwise only achieves mediocre results. In the following year, I came to realise that no one among my fellow students or in my first jobs even considered the possibility of regularly reading a foreign economic magazine or ‘serious’ literature.

It is worth mentioning that other than stumbling upon an interest in the business world, I learnt very little about the economy at university: useless neoclassical supply and demand charts, with a supposedly rational human being and a non-existent equilibrium, and little more. Thank goodness Hayek and von Mises came to my rescue nearly 20 years later, like economic superheroes. It is a real shame that economics teaching doesn't develop clear and simple concepts that are able to stand the test of time. Since some people want to give it an air of importance that it doesn't have, a façade of mathematical formulations has been erected to hide the lack of clarity and coherence of neoclassical economists, both monetarists and Keynesians, who dominate economics teaching.

However, it was a varied degree, which enabled me to begin to get a handle on potential areas of interest, or at least rule out possible paths to follow. My grades were mediocre to begin with, but gradually improved as I began to connect with the material.

Looking back, one of the most interesting conclusions I have reached after five years in a not especially prestigious public university, and many more years of professional experience, is that the importance attached to prestigious universities, and even university teaching itself, may be overstated. What you learn at 20 years of age is not as important as lifelong education – preferably when it is self-taught. Three or four years of being put on the right path by good professors may be useful, but the key thing is to have a spark of interest awoken in us at a particular point in time, which opens up an appealing and limitless path. It might be the case that some of the big universities help this happen, but I am not sure it's the case. And I cannot understand the current obsession, especially in the English-speaking world, with getting into certain universities. In my home country of Spain we are fortunate that there is not such a heavy emphasis on attending elite universities.

In my case the spark was ignited by an adolescent reader and a professional basketball player.

FIRST JOBS

In my last year of university I responded to various job adverts to practise the art of the professional interview. After the very first interview, I was offered a job at El Corte Inglés. I don't think I was a specialist in interviews, but if I do have any special qualities it is that I am natural and exude a certain air of being a responsible person. This unexpected success forced me to decide whether to start work before graduating in June. I decided to start in March and spent four months combining both work and study, and a football World Cup with Butragueño, the Spanish star, and Maradona.

I spent a year working at El Corte Inglés, the leading Spanish retailer (until Zara turned up), where I graduated in administrative work. This didn't offer me much on a professional level, but it was useful on a personal level. In my department at least, El Corte Inglés tried to hire university graduates for administrative tasks. It was an approach that obviously didn't work, and little by little the majority of us ended up leaving. Either way, starting out professional life doing relatively thankless tasks toughens one up for what might come in the future. To my surprise, I also discovered that a lot of people are happy doing a simple and uncomplicated job. It is possible that they are making a virtue out of a necessity, but this simplicity is something that has passed through my mind later in life, at moments of excessive responsibility.

On El Corte Inglés itself I can't say a great deal. I was there only 15 months, and my job position didn't afford me a wider perspective on the group. That said, there was a strange contradiction between the visually attractive shops, perfectly arranged and with impeccable service, and the somewhat outdated and highly hierarchical internal organisation. It is likely that things have changed after 30 years, enabling a transition towards more modern forms of distribution after the significant decline in popularity of the ‘department store’ concept around the world.

I certainly didn't see it as a job for life, meaning that I took it upon myself to do what you have to try at times of professional stagnation, when you are stuck without knowing where to go: think outside the box and change your life. This involves considering something radically different, tearing down previous plans. In my case, I went down the road of an MBA (Master in Business Administration). You might think that going from a company such as El Corte Inglés to studying an MBA is not such a radical change, but I can only attest to the sensation I had when visiting the MBA campus in Barcelona for the first time, of feeling very different.

Young people often ask me whether they should do an MBA, CFA, or other alternative. The response depends on each individual situation, taking account of their partner, ambitions to form a family, clarity of ideas on the future, work at that time, financial situation, etc. My case was clear: I was single and unattached, with a relatively uninspiring job and lacking clear professional ideas. I ticked all the boxes for doing an MBA.

IESE

After spending the summer months in the American multinational NCR (I had decided to change jobs, but I was accepted into IESE – Instituto de Estudios Superiores de la Empresa), I headed to Barcelona in September 1987 to do an MBA in what was and continues to be one of the best business schools in the world. Spain has an impressive number of high-quality business schools: IESE, IE, Esade. If only the universities could learn from them!

As a curious aside, I had to repeat the mathematics entrance exam. I guess I did the others pretty well, because otherwise they would not have given me the opportunity. As we will come to see later, good investment doesn't depend on exceptional knowledge of maths, but rather knowledge of dynamic business competition and a simple calculator.

I took out a loan with the Catalan bank, La Caixa, which had an agreement to finance IESE students (with an eye to their future earnings potential), and settled down in Barcelona. I felt very comfortable in Barcelona, both with the institution and the surrounding environment, made up of professors and students from 20 different nationalities. The self-sufficiency which I had experienced until then, due to the ease with which I had passed exams, gave way to something different: I discovered that some of my colleagues were brighter than me or, at least, were able to concentrate better. This had been true before, but I had always justified it to myself on the basis that I hadn't made a wholehearted effort. This excuse was no longer valid in Barcelona, where I did try to give the best of myself.

I think this ultimately helped me to focus on the future, knowing that I had to follow my own path, knowing that there will always be better and worse people than me, professional speaking (and personally as well).

The other hallmark that I was left with from the MBA was a certain dose of scepticism. Maybe it was the continual case study analysis, IESE's main teaching method, and the debate with other equally well-educated young people, which left my colleagues and I with a veneer of scepticism that I used systematically from that point onwards. Cases always have multiple solutions, and there is never a single response; no one is certain of being right, even less so when surrounded by people able to demolish their arguments. As investors, we are constantly being told very attractive stories. We are sold hopes, futures, triumphs, and our job is to choose only those stories or projects which are worthwhile.

I also had my first experience of a stock-market crash in October 1987. Strangely, back then, I viewed my flatmates, passionate stock-market investors, as irredeemable speculators. Clearly, I was still showing few signs of being a ‘financial whizz-kid’. How was I going to get involved with money? How things change…

The clearest and most decisive conclusion from those two years in Barcelona was that analytical activity suited my personality. I was lucky to be able to apply the classic and essential ‘know yourself’ refrain. Others never find themselves, despite frantically searching. For me it was clear. I was not somebody suited to sales, or leadership, but rather study, reflection, and reading: in one word, analysis.

BESTINVER

Competitive and financial analysis looked like a professional field that matched my qualities, but I was still unsure which area of analysis I should focus on. The same type of analysis could apply to strategic advice, buying or selling a company, or investing in another, listed or otherwise.

The decision had to come from somewhere, and circumstances ultimately intervened.

I jumped directly from IESE to Bestinver, after two strokes of luck. I had already received an offer from a relatively prestigious consultancy firm – Coopers & Lybrand – but I went along to an interview with Bestinver after realising the night before that none of the other possible candidates were going to show up, as we were celebrating the end of term in advance…

I didn't think it was right to give such a bad image, and so I went to a very subdued interview, knowing that I wasn't overly interested. The added twist of fate was that Coopers had offered three positions to four people, assuming that one would fall by the wayside. No one dropped out and, as I was the last to reply, I was excluded. Let's just say that at the height of summer I was left with little option but to accept the offer from Carlos Prado and José Ignacio Benjumea to work with Bestinver as an investment analyst. In reality, it was not a conscious choice. At IESE I had not stood out enough to aspire to join McKinsey, Salomon Brothers, BCG, or any of the other big hitters at that time – which we all ultimately aspired to work for – and my decision was driven by circumstances. I took what was on offer to me in an area related to analysis.

At that time, Bestinver was the diversification arm of the Entrecanales family. I have to confess that I was impressed both by their red/maroon offices, which had a certain air of a house of ill-repute, in the prestigious La Pirámide building in the centre of Madrid, as well as by the company's Director General, José Ignacio Benjumea, who was amiable with me from the outset, as he has been over all these years. In any case, on top of this sheen of glamour, it struck me that Bestinver offered what I was seeking: a small environment, with interesting people, backed up by the discreet support of a very sound institution.

I was hired to help analyse the group's potential diversification investments. At the time, Bestinver had three areas of activity: diversification, which sought to channel profits generated by the family's construction activity towards new businesses, and where some investments had already been made; a stock brokerage service, which had been liberalised around that time and where the company had some presence; and a tiny portfolio management business.

It was a special time to start working. It was August 1989 and in autumn, Eastern Europe's totalitarian regimes began to topple. Having followed, from a very young age, media stories on the adventures of those who tried to escape, it was a time of widespread optimism, and we were keeping a very close eye on the news coming through to us on the office television. At the same time, Spain was heading at full steam towards entry into the European Union (EU). It was not a bad time to be young and setting out on a professional endeavour.

In the first few months I tried to scour the market to find private unlisted companies, seeking investment opportunities for the group and offering these companies the option of being listed on the stock exchange. I was allowed to do this without clear instructions and with a lot of flexibility; I guess they were not very clear about what they wanted from me. However, I didn't like the commercial part of the work one bit, essentially cold calling. This confirmed my lack of propensity for it and the limited analysis I was able to do on possible transactions did not offset this.

In fact, I wasn't very clear who my boss was and on my own initiative I started to study listed companies, helping the three brokerage agents and the small equity analysis team which fed them information. It's probably because of this that later in life I have put a lot of emphasis on my own initiative, free from guidance. This is my approach to management, when I have had to work with colleagues. If we wait for somebody to solve our problems by giving clear instructions, it is more likely that Godot will show up first.

MY INITIAL ANALYSIS AND INVESTMENTS

Acerinox, the leading stainless steel giant, was the first company I visited and analysed at the end of 1989. Back then it struck me as being an exceptional company, and that remains the case to this day. However, I guess I was too timid and I recommended ‘holding’. Little by little I began to realise that I could add value to the analysis, and in my free time, which I had quite a lot of given the lack of a clear remit, I set myself the challenge of becoming acquainted with all the companies listed on the Spanish market.

At that time the CNMV (Spain's National Securities Market Commission) produced a book with the quarterly results of all listed companies. I reviewed them all, from A to Z. I think that the first one was Agrofuse, a company involved in the farming business, which we never invested in. Throughout 1990 I spent my time doing this, with the good fortune of not having to respond to pressure from a boss, or a structure that demanded short-term results or output.

At the start of 1990 I read a review of Peter Lynch's book One Up On Wall Street1 in Business Week, which I had continued to read regularly since university. The book explained the fundamentals of value investing (or sensible long-term investing). In fact, as I have already mentioned, until very recently I still believed this book to be so complete and clear that it wasn't possible to add much to what had already been said.

Value investing aims to invest sensibly over the long term, estimating companies' capacity to generate future earnings and paying a competitive price for them. This sounds self-evident and something all investors should do, but they don't, so in reality, value investors are simply sensible investors.

| Acerinox (update) last statement: January 88 | |||||

| Date: 30 November 1989 | |||||

| Price: 1,305% (13.050 ptas) / 30 November 1989 | |||||

| Consolidated Group (millions of pesetas) | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 (F) | 1990 (F) | 1991 (F) |

| Sales | 46,509 | 76,660 | 85,000 | 101,200 | 116,500 |

| Share capital | 6,050 | 7,323 | 8,639 | 8,639 | 8,639 |

| Net profit | 5,078 | 10,306 | 8,600 | 14,100 | 16,730 |

| Net cash flow | 12,188 | 16,347 | 12,600 | 18,600 | 21,230 |

| Earnings per share (pesetas) (*) | 625 | 1,286 | 995 | 1,632 | 1,937 |

| Free cash flow per share (pesetas) (*) | 1,684 | 2,039 | 1,459 | 2,153 | 2,457 |

| Gross dividend (pesetas per share) | 182 | 200 | 200 | 225 | 250 |

| PER (*) | 20.9 | 10.1 | 13.1 | 8.0 | 6.7 |

| RPCF (*) | 7.7 | 6.4 | 8.9 | 6.1 | 5.3 |

| Dividend yield (%) (*) | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Market capitalisation (millions of pesetas): | 112,738 | Price/book value | 2.2 | ||

| LAST TWELVE MONTHS: | |||||

| QUOTATION FREQUENCY (%): | 95 | Maximum (%): | 1,860 | ||

| Average daily volume (shares) | 14,762 | Minimum (%): | 1,067.5 | ||

(*) Figures adjusted for rights issue. (F) Forecast.

Income Statement

| 1987 | 1988 | 1989 (F) | 1990 (F) | 1991 (F) | |

| Net sales | 46,509 | 76,660 | 85,000 | 101,200 | 116,500 |

| Cost of selling | 20,749 | 40,934 | 53,550 | 61,700 | 69,900 |

| Gross margin | 25,760 | 35,726 | 31,450 | 39,500 | 46,600 |

| Personnel cost | 4,837 | 5,831 | 6,500 | 7,400 | 8,100 |

| Other costs | 6,217 | 7,032 | 7,800 | 8,500 | 9,200 |

| Depreciation | 7,110 | 6,041 | 4,000 | 4,500 | 4,500 |

| Provisions | 112 | 2,469 | 400 | 500 | 600 |

| Exchange rate variations | 102 | (571) | — | — | — |

| Other income | 494 | 479 | 500 | 2,500 | 500 |

| EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) | 8,080 | 14,261 | 13,250 | 21,100 | 24,700 |

| Interest expenditures | 1,938 | 859 | 1,300 | 1,000 | 800 |

| Pre-tax income | 6,142 | 13,402 | 11,950 | 20,100 | 3,900 |

| Taxes | 1,064 | 3,096 | 3,350 | 6,000 | 7,170 |

| Net income | 5,078 | 10,306 | 8,600 | 14,100 | 16,730 |

| Net cash flow | 12,188 | 16,347 | 12,600 | 18,600 | 21,230 |

Thanks to Lynch I discovered the other investment maestros: Graham, Buffett, Philip Fisher, Templeton, etc. I wrote to Omaha and they sent me all Warren Buffett's letters to shareholders that had been published at the time. I have always said that his timeless wisdom, outside of the MBA network, is the best Master's degree for a student of the business world. Not just professionally, but also personally. We will turn to him in more detail later on.

Overall, 1990 was a key year in my training as an investment analyst and manager, during which a series of very significant factors came together:

- I had found the type of work that suited my key personality traits – analytical capacity and patience. It was a relatively quick and pretty clear process.

- In Santos Martínez-Conde I had a head of analysis with a very clear ‘value’ approach. Although at that point he was unfamiliar with the American maestros, he applied fundamental valuation to all investment opportunities. I spent 18 months working with him until he left in January 1991, and he left an opening as head of analysis which I asked to fill. He is now Chief Executive Officer at Corporación Alba, the March family's investment holding company.

- I had total freedom to analyse the companies which I considered to be of interest, at my own pace. This rounded out my education, as we will see.

- I discovered Peter Lynch and Warren Buffett. And all the rest.

- I had my first practical lesson on volatility and ‘uncertainty’. On 2 August 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait, provoking a global crisis which had implications across the markets. The S&P 500 fell 20% in three months, from peak levels in July prior to the invasion to lows in October. This period of uncertainty proved to be an optimal time for buying shares. On 17 January 1991, a coalition of states invaded Iraq, provoking an upward movement in the stock markets and a recovery of pre-invasion peaks in less than a month. As the classical investors had always maintained, buying bad news was the best way to take advantage of ‘uncertainty’.

Using this guidance I sensed that there was a clear gap in Spain for applying what Americans called ‘value’ investing. The stock market in Spain was dominated by large banks and by the heirs to the old stock and exchange brokers, notably Asesores Bursátiles and FG. However, sensible fund management was scant.

This is essentially how I laid the groundwork of my training. These lessons have remained with me until now, and I have never had cause to doubt them. I would have liked to have given a bit of ‘spice’ to this part of my story, describing my doubts, qualms, and ups and downs, but I can't, because the natural doubts that we all face before taking on a profession rapidly came to an end that year on the basis of a single year of experience. I suppose in that sense I am one of Stendhal's happy few. I was 26 years old and I had a clear vision of my long-term future.

When young people ask me how to get started with investing, I always say that they have to start right now. There are two options. The first is that some charitable soul in the markets will come along and offer you a work opportunity related to investment analysis or management. This makes life easier, provided that bad habits are not picked up, which can later prove hard to shake. The second, more likely, option is that you have to self-teach, working in other jobs to support yourself while learning about investing correctly in your spare time. Fortunately, there are a lot of resources out there these days to help you.

I was lucky enough to spend a year mid-way between the two, I was paid by somebody but I was allowed to choose how I spent my analytical time. Either way, the crucial thing is to create your own portfolio from the outset. The amount that we invest is irrelevant, the key is organising an effective process, which suits us and, if possible, actually works. How are we going to convince others to give us an opportunity if we don't believe in it ourselves!

Another key landmark was in February 1990, when I bought my first shares. Up until then I had never even considered it. As I have already mentioned, unlike other investors I never had an entrepreneurial spirit as a child, young person, or young adult. On the contrary, it struck me as a world inhabited by speculators, far away from my own world, which tended to be somewhat intellectual. I bought Banco Santander shares. Back then it was a much easier-to-analyse bank than it is now: its business was growing in Spain, thanks to its aggressive commercial policy – that year it launched the first deposit war with the ‘superaccount’ – and its small-scale forays abroad; it was trading at a reasonable price – nine times earnings – which didn't reflect its past or future growth capacity. I recall being nervous throughout the morning until the order was finally confirmed. It was a tiny order – just 50 shares – but it marked a turning point in my life. (Furthermore, this also shows that I am not genetically ill-disposed to investing in banks, despite not having done so from 1998 to 2012.)

This was the start of my portfolio of personal investments. I cannot comprehend how somebody who analyses the markets, providing buy or sale opinions or managing money, can refrain from becoming a shareholder in the companies they like. In my case it was an unstoppable urge: I analysed companies and if I liked them, I had to buy them, even if only in small amounts.

Sometimes there are legal restrictions in place, but there shouldn't be a problem provided you are transparent. Later on, when tax-free fund transfers were established, I gradually wound down my portfolio in order to invest in funds, which was the logical thing to do (before then I worried that if I ever fell out with Bestinver and decided to change company, I would be liable to pay tax on the corresponding capital gains when selling my funds).

This first purchase was the start of the process of building a portfolio of stocks. It seemed like an ideal moment. The environment was very positive on the back of the fall of the Berlin Wall and Spain's entry into the EU, and reasonable prices meant I could buy good assets at a good price. I even decided to take on a bit of debt. I calculated my savings capacity over the following two to three years and, taking account of repayment of the loan from La Caixa which funded my Master's degree at IESE, I asked for three loans, each worth 1 million Spanish pesetas ($6,000): from my father, my friend Miguel del Riego, and my bank.

It is the only time that I have had to take on debt to invest. I didn't have any family commitments and I did so modestly, after estimating my probable income and with at least two very flexible backers. I have always urged a lot of caution when taking on debt. There can be exceptions – this is one example – but always on the basis that we can withstand very negative scenarios, losses of more than 50%, without suffering a risk of default.

I started investing this money in different Spanish stocks on a small scale: Ence, Tafisa, Nissan Motor Ibérica, Cevasa, Inacsa, Tudor, Fasa Renault, etc. The advantage of being a small investor is that with little money you can take on positions which have an impact on a group of stocks. This portfolio convinced me that I liked managing money and that I could do it reasonably well. I also made a very serious error, which – luckily – didn't cost me too much money or pride: Nissan Motor Ibérica.

Nissan Motor Ibérica was the Spanish subsidiary of the Japanese multinational automobile manufacturer, Nissan. It had an attractive position in industrial vehicles, with various production facilities on Spanish soil and sales across Europe. Thanks to Lynch's teachings, I believed I had good knowledge of how to invest in cycles and how to identify growth companies. I saw Nissan as a growth company from Spain to Europe, with new vehicles on the way, especially for passengers, where it currently did not have a market presence. Its recent track record backed up the growth idea.

However, the slowdown in the Spanish economy following the hangover from the 1992 festivities – the Barcelona Olympics and the Seville Expo – saw cyclical stocks begin to suffer significantly. Sales in my wonderful growth company collapsed, turning it into a vulgar cyclical company.

During the fall in its share price in 1990 and 1991, I had systematically increased my positions, with Nissan Motor Ibérica stock at one point reaching 40% of my personal portfolio. As we will discuss later, increasing positions in a stock in freefall is one of the hardest decisions an investor can make; sometimes you never recover the full extent of the fall. Though it is true that in cyclical companies, sooner or later the situation will change, meaning that despite everything, persisting with the purchase normally bears fruit.

Investment in Nissan Motor Ibérica

| PURCHASE | |||

| Date | No. shares | Price (pesetas) | Total (pesetas) |

| 18 April 1990 | 100 | 814 | 81,400 |

| 10 December 1990 | 400 | 378 | 151,200 |

| 27 December 1990 | 500 | 339 | 169,500 |

| 18 February 1991 | 700 | 495 | 346,500 |

| 19 February 1991 | 50 | 500 | 25,750 |

| 1,750 | 774,350 | ||

| SALE | |||

| 27 January 1994 | 1,750 | 260 | 455,000 |

| LOSS: 319,350 | |||

Losses on Nissan Motor Ibérica accounted for 40% of the investment, on top of the opportunity cost of three good market years.

The company eventually had major problems, nearly going into bankruptcy. Only a rescue takeover by the parent company in 1994 enabled losses to be limited at around 50% of the initial investment.

I learnt an important lesson from the excessive focus of my portfolio on Nissan: even when we are totally convinced of our convictions we can get it wrong, making it vital to diversify our investments. Mercifully, thanks to the success of my other investments, I didn't lose confidence in my ability to choose stocks and I was able to amply cover the losses on Nissan.

We have all been in versions of this type of situation in bars, with family, and we will continue to experience them. Thankfully.

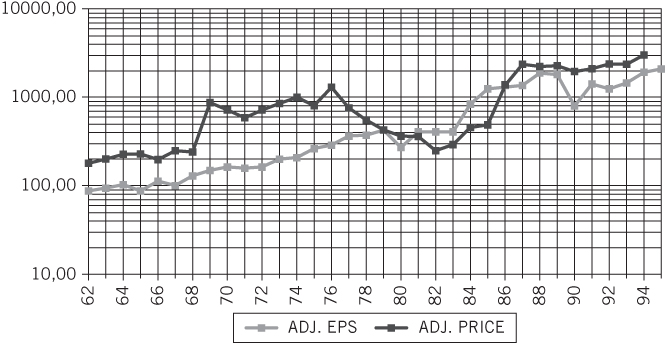

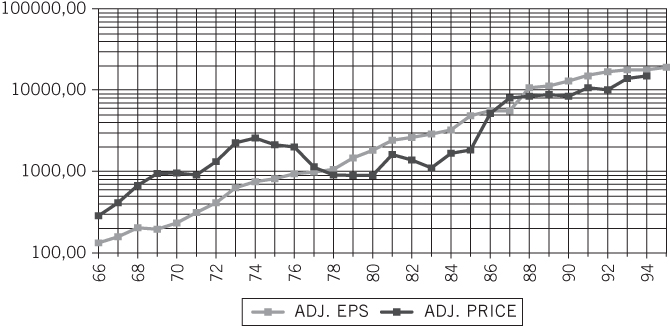

Lynch's charts, which relate earnings and share prices, perfectly illustrate how the long-term share price faithfully mirrors earnings developments. We have tried to reproduce these charts for Spain, as can be seen on this and the next page.