Chapter 1

The W3 (Who, What, and Why) Framework

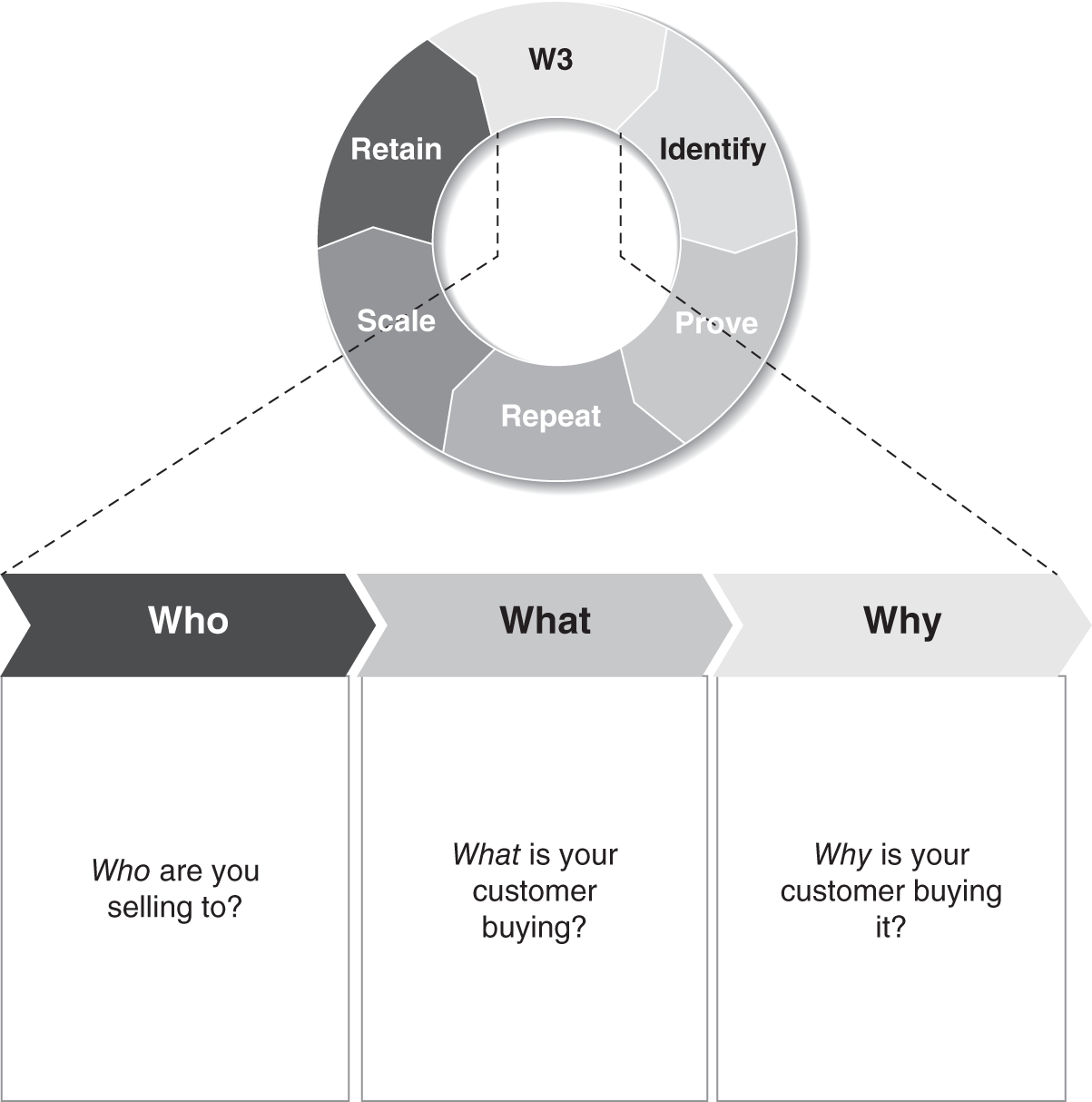

Figure 1.1 The W3 Framework (Who, What, and Why)

At the start of Techstars 2017 program, I remember proudly announcing each KPI meeting that “Sales were great this week … and we have no idea why.” Amos constantly reminded us that we needed to know the triggers of our business to have any control over our growth trajectory. We ultimately realized the answer to the 3Ws was the missing ingredient, and explained exactly what was preventing our company from massive scaling: we had achieved product market fit only among super-users in a niche market. We had a false sense of confidence because it took no effort to sell to our (few) optimal users, but it was extremely difficult to sell to anyone else.

—Guy Goldstein, founder and CEO of WriterDuet

Where the Heck Do I Start?

No business can exist without paying customers, which means no business can exist without sales. It's relatively easy to look at any company, especially one doing well, and be able to describe who their customers are. However, when you are first building your business all you have is a theory of who you think your customer will be, based on your theory of the problem you are solving and your opinion of what you want to sell them. While it's important for you to have a strong point of view to get started, it's even more important to figure out if you are right before you get too far along. The repercussions of being wrong can be very expensive and can even cause your business to fail.

We've all heard stories about companies pivoting their product or customer focus. I've personally witnessed it dozens of times while working at startups and now with Techstars Austin. Pivots, small and large, are often crucial to figuring out how to build a big business; however, without a framework to figure out who your customer is, what they are buying, and why they buy it, ensuring your success is like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

In this chapter we'll discuss the W3 Framework (Figure 1.1). This is what I used at Business.com, mySpoonful, and BlackLocus. It's also the framework I encourage my portfolio companies at Techstars to use. I've broken this chapter into five parts to make it a little more digestible.

This section is a description of W3, the framework I recommend identifying your ideal customer profile (ICP) and why it's important to start this work early on. In the second, third, and fourth sections, we'll dig into each of the three Ws.

“Who” Are You Selling To? explores identifying the who—who you believe your customer is and how you go about validating it.

In “What” Is Your Customer Buying? we will dig into the what, meaning what product or service you are selling (compared to what the customer is actually buying). Likewise, we will explore how you can validate that you are selling the right product to the right buyer.

And finally, in “Why” Is Your Customer Buying It? we will discuss the why of your business—why your customer is buying your product and how your customer will measure the impact on their business.

In the fifth section “Putting W3 Together,” I'll present you with an in-depth exercise to help you thoroughly outline your sales plan.

* * *

Startup founders, especially in early-stage companies, often develop their sales plan based on their personal (and hopefully deep) understanding of the problem they are trying to solve and the product they are bringing to market. However, in my experience, most founders are not great at articulating exactly what they're doing or why. Founders may have a strong idea regarding who their customers will be and what their product or service will be. But in most cases, very little is done to validate their theory and even less is done to capture it in a way that is easy for anyone to comprehend. In the early days of starting your company when you are the one selling to customers, this is fine. However, this immediately becomes a problem when you start trying to hire, forecast, and raise money. The problem with not having an articulated sales plan is that you leave employees, candidates, investors, and even potential customers guessing at who buys what and why, and this, in turn, results in a lack of alignment, clarity, and confidence in the future of your business.

I've now been running sales organizations for over 20 years. Early on, I too failed to understand the importance of a clearly articulated sales plan. In fact, the concept of taking the time to articulate and write down a formal plan seemed like a giant waste of time. Worse, if what we were doing and why we were doing it wasn't obvious to someone, I questioned their intelligence or commitment to the company.

I was wrong.

At that point in my career, I hadn't been around enough experienced leaders building real (and big) companies to understand the importance of planning and process. I also didn't have (or even understand why I should have) mentors to help me grow. This was all on me to figure out. The good news was, my parents were both excellent role models for my strong work ethic. They had a keen and insightful worldview and taught me early on how to think about the present, but also about how events of today will affect the future. I've always had good intuition when it comes to business and over the years I've learned to trust my gut (and I could write an entirely different book on that). What I lacked was anyone ever showing me how to connect the dots from what was in my head and translating that into a plan to build something amazing.

Connecting the Dots from Thoughts to a Plan

In 2005 I was recently promoted to run sales and client services for Business.com. I finally realized just how important it was to articulate what “our” plan was—and why it was that way.

Business.com was an earlier-stage company poised for huge growth but had not arrived there yet. We had around 70 employees, in the mid-seven digits of revenue, and were selling a business-to-business (B2B) search product in the early days of Google Adwords. My predecessor did an incredible job getting us to that point and when his role evolved to focus more on corporate and business development, I was asked to step in for the next iteration of scaling our sales organization.

By this point we had a very experienced leadership team made up of ex-Yahoo, eBay, and Careerbuilder execs and a seasoned board made up of partners, founders, and CEOs from Benchmark, IVP, Earthlink, Boingo, shopping.com, PayPal, and LowerMyBills. While I had great intuition on developing a plan and some raw talent at sales, I had very little classical business training (i.e. no MBA and to this point no great mentor to teach me). It wasn't until I was asked to present my vision to the board that I truly realized the importance of defining and articulating a sales plan.

Fortunately my CEO, Jake Winebaum, was (and still is) an incredible strategist and likewise very good at cultivating raw talent. He wouldn't let me present anything less than a world-class plan and pushed me very hard to develop and articulate mine—this is where I truly learned the importance of taking what was in my head (and gut) and putting it on paper for everyone in the organization to see.

The best way for me to describe to you the weeks of intense mental work I put into developing this plan is to tell you about Jake's ability to ask one simple question: Why? Jake asked me “Why do you believe this to be true?” at every stage and about every aspect of the plan as it evolved. Multiple times a week I'd be in his office sharing the next iteration of the plan, and week after week I'd leave asking myself the same questions he was asking me. At times this was frustrating and borderline infuriating because I really never had anyone question or push me to that level of detail and specificity in the past, but ultimately it was one of the most valuable experiences I've had as a professional (and one I've carried forward with my work at Techstars).

What it forced me to do was dig inside my instincts and look for opinions, facts, and data to support what my gut was telling me. Sometimes that would help me support my opinion and other times it helped me to see potential flaws and areas of risk. Ultimately, it gave me (and him) the confidence to present the plan to the board and eventually the entire company because we knew we had something that we can easily articulate to anyone, the data to support the direction, and an understanding of the areas of risk.

I called my plan W3, which stood for who, what, and why. I presented it to the board and executive peers. They all bought in. Then I rolled it out to the sales team, making sure that everyone grasped both what we were doing and why. The result was amazing. Immediately we saw alignment across the entire sales team and across the company, which contributed to massive revenue growth (mid-seven to mid-eight digits) over the next 18 months, and eventually a sale of the company to R.H. Donnelly for $345 million.

Required: A Solid Sales Plan

I want to take some time to describe the alignment and why that was so important. It's not that Business.com didn't have a clear vision; we did. We were also fortunate in that we had a healthy culture of people who loved the company, loved the mission, and believed in Jake as CEO (and the rest of the leadership team, as well). What we lacked was alignment in how to grow our sales in a meaningful way. Sales reps had little direction regarding what was best for the business versus what was best for their commission (or that those two things could be aligned). Also, while our product and marketing teams were very strong, there was virtually no alignment on how product, marketing, and sales all informed each other in a way to accelerate growth. What W3 did for Business.com was to bring all of the pieces together around common language and mission so that we all had a strong sense of how to work together and build a very big company.

That experience was incredible in terms of helping me understand how to build a big and valuable business. More specifically, I learned that in order to have a working, growing, and effective sales department (and company) you need a well-defined and articulated sales plan. This is not a suggestion: it is a requirement. Having a strong plan that the entire team can believe in and get behind drives sustainable results.

So what is W3 and how can you use it to build and grow your sales organization? W3 is a framework for developing your plan. It stands for the three most important attributes of a sale: Who are you selling to? What are they buying? and Why are they buying it?

In the next three parts, we will dive into each W separately. Some of this may seem really obvious while other parts could feel tedious. I'm sharing this with you in advance because I want you to be prepared for taking the time to put in the work. This will be the foundation both for everything else in this book and more important to helping you figure out how to build a great sales organization and incredible company.

Who Are You Selling To?

If you don't know your WHO, your WHO becomes everyone. This means engineering becomes swamped with features to make anyone/everyone happy. Sales can't build repeatability; marketing has to build a message that resonates with everyone. Targeting everyone means you become the best for no-one. Your WHO aligns your company's teams, and gives you the ability to focus and execute in a single direction.

—Noah Spirakus, founder and CEO of Prospectify

Who are you selling to? What is your target industry? What segment(s) will get the most value? How do you identify and prioritize targets? Who is the target buyer within each company? What is the job title of the typical buyer? How do we know we are right?

These are just a few of the questions you will start to answer as we go through this section. It's at this point that you may be saying to yourself, “I know who my customer is” and feel that you can skip this. Pause. Ask yourself why you believe that. What is the reason you believe you know who your target customer is, and what data do you have to support your theory? To what level of granularity can you describe your target customer? What can you do to prove you are right (or prove you are wrong)? Can everyone in your company describe, specifically, who your target customer is?

I know there are a lot of questions here. Remember when I said this might feel tedious? This is the time to open up your laptop (leave your email and iMessage closed) and start answering these questions (writing down any new ones that pop up).

Before we do that, I want to talk more about how we will approach defining who. My experience shows that most startup CEOs (and even many startup sales leaders) can quickly describe the high-level version of WHO they believe their customer is but stop there. Let's use Transmute, one of my portfolio companies, as an example. Transmute has created a new identity protection and management platform using blockchain technology. While this product could potentially help any company of any size, in this example the CEO has already narrowed down their target customer. When Transmute entered Techstars, if you asked the CEO who their customers are, she would have responded, “We sell to enterprises.”

This was a good start. They had already cut out a huge number of potential customers where they will not spend their time selling, but what kind of enterprise is Transmute targeting? She could have meant software, retail, healthcare.

She may define enterprise as a company with above a specific number of employees or revenue threshold. If I'm trying to help this company, I'm still not sure where to start.

My next question for this CEO was, “What type of enterprise?” The CEO was able to take it a step further and say, “We sell to enterprises in the healthcare space.” This was a better start as it plants a flag in the ground, but there is still a lot more work to do. I still wasn't sure if they meant hospitals or software companies selling into hospitals or medical device companies or something else. I was also unsure of who I could contact inside that company who cares about the problem that their product solves.

It's likely you've gotten to this level of granularity, and maybe even a little further. At this point, you have two more jobs:

- Get more granular

- Disprove it

Job 1: Get More Granular

This is a conversation I have with every single founder I invest in, and the conversations are often heated. What I will assert is that you want to define the narrowest and most specific customer type that you can in the beginning. Here is an example of how Transmute could think about it to ultimately identify their target customer, “We sell to enterprises in the healthcare space. These are private hospitals with over 5,000 employees. Those hospitals currently have two specific legacy products focused on patient identity protection and have had a breach in the past 90 days. The buyer in those hospitals typically has the title of director of security and information.”

Take a minute to notice what we did here. We took an important directional flag indicating who we believed our customer to be and formed an opinion about a much narrower potential customer type. This is often where I start getting pushback, specifically the retort, “This is too narrow and will limit my ability to build a huge company. Investors won't see the potential scale and our sales team will feel too limited in making commissions.”

While on the surface this may feel true, it's actually the opposite. Keep in mind that right now all you have is a strong belief of who your customer might be and not enough data to prove it.

By defining the narrowest possible group of customers, what you are actually doing is starting to build out a case, using data, that there is a definable group who does buy your product and can't live without it. This is critical in any stage of your business but especially in the earliest stages where all you have are theories. And while it might feel like you are limiting your growth potential, what you are actually doing is building your business around exactly the right customers to buy your product. These customers will inform how your product evolves as well as giving you more data on who the next set of customers could be. They also become the case studies and proof points that you can point to that show that your product works and brings value to your existing customers. Or, you'll quickly learn that this is not meant to be your target customer and you can shift direction before spending too much time or money in a single direction.

Pause here for a minute. Think about how you've been talking about your potential customer set. What are the questions you've been getting? What is the feedback from colleagues, investors, and potential customers? If you haven't yet, take a minute to write down specifically who you believe your customer will be. At each level of granularity, also write down why you believe that to be true. This is important as we get to your second job. In “Putting W3 Together,” we also use this as part of building out your sales plan.

Job 2: Disprove It

Yes, you read that correctly: disprove your own theory. Your job now is to figure out why you are right by trying to prove why you are wrong. This concept is one you'll hear from me over and over again. Of course the first thing you need to do is to validate why you believe you are right, followed by exploring why you might not be.

So what does that look like? It starts with taking that granular definition of who you believe your customer is, creating a list of 20–30 companies who fit on that list, and talking to them. Don't sell them, learn from them. We'll get into this in a lot more detail later on in the book when we talk about the difference between sales and customer development, but for now just start to think about what these conversations might look like.

The second part of that, which is job 2, is to see if you can prove yourself wrong. There are two ways to think about this. Am I wrong about the customer segment I've defined? Are they short-term customers? Are we really solving a huge pain for them? Is this really the right person in the organization to sell to? Or, is there a granular customer definition that is stronger? Will we be able to sell more, or faster, or for more money? Is there someone out there who needs us even more? Part of job 2 is to define one to two additional potential customer segments. Then try to stack-rank them. With limited time, you can probably only prioritize one group and reprioritize as you learn. This will give you the basis for proving and disproving whether your top-ranked customer set is right (and hopefully help you determine your next customer priority).

And then you have to start the process all over again.

* * *

Right now you are probably feeling a little overwhelmed. Either you are questioning how important this work really is or trying to figure out how you do this as quickly as possible. You probably don't have a lot of time or money before you need to start generating (more) revenue. That's totally normal, you should feel a bit overwhelmed. Starting a business is hard and it's a lot of responsibility. You are probably feeling the pressure of both time and money and wondering how you can do this and still hit those important milestones to raise money or slow your burn or even be profitable. Am I trying to freak you out? A little. But, more important, I'm giving you a playbook to help you avoid costly mistakes, so as you do grow you can sell more faster!

Now we've discussed who you believe your customer is, in the most granular way possible, as well as who you believe your next one or two customer sets might be. So what comes next!

What Is Your Customer Buying?

Identifying WHAT your customers are buying sounds obvious but it's actually much more nuanced. In fact, when you are a startup sometimes even your customers don't know what they are really buying from you. They only know what they think they want. Until you figure this out, you have no chance of building a scalable sales team.

—Kurt Rathmann, founder and CEO of ScaleFactor

What product is your customer buying? Even if you aren't sure yet who your customer is, you probably feel like you can answer the question of what you're selling with a high degree of confidence. There are two challenges with this that every startup faces. The first is, you may be wrong. Most founders get this on some level and know there will be some amount of iterating or pivoting in the pursuit of “product–market fit.” What most founders and even sales leaders often overlook is that the product you are selling is often not the product the customer is buying. It's deeply important to understand that too, because it gives you the ability to identify the right buyers, craft the right pitch, and develop long-term relationships with your customers.

“Huh? What do you mean that my customers buy something different than I'm selling? That doesn't make any sense.”

What You're Selling versus What the Customer Is Buying

Let me give you two examples to help paint the picture. In the first example we will look at one of my portfolio companies: LIVSN. LIVSN sells outdoor apparel for hikers and climbers. Their marketer believes that Google Adwords is a place to find customers. I will assume most people are familiar with buying Adwords on Google. In this case, Google is selling placement on a search results page specific to keywords that a Google user is searching for. Google's product is a platform to facilitate that ad buy. Is that what the marketer is buying? On the surface, yes. Dig one level deeper and what the marketer is actually buying is the attention of hikers and climbers who are in need of new apparel. Fortunately Google knows that is what the customer is buying and because of this has a stated focus (built into their product) to deliver high-quality customers for this company.

In our second example, let's look at a company that didn't initially understand the difference between what they were selling and what their customers were buying: BlackLocus.

When I joined BlackLocus, we were selling a platform that provided insight into online retailers' competitors and overlapping products. The emphasis in what we were selling was (a) the platform and (b) a snapshot in time of each customer's top competitors. What this led to for us was a misalignment with our early customers and resulted in unhappy customers and churn. However, after many customer interviews, what we learned was that (a) platform only opened the door to questions and didn't really provide anything actionable, and (b) it was more important for our customers to know how their TOP products competed online regardless of who the competitors were. While subtle, understanding these two differences helped us shape both the product and the pitch. We ultimately iterated our product to focus on our customer's products (not their competitor's) and also included suggestions (based on competitive landscape data) in the platform. These changes were instrumental in both figuring out who our customers “should be” as well as understanding how we exchanged value (product for money) with them (we'll cover this concept in more depth in Chapter 4).

To reiterate and be overly direct, there is a very important and single takeaway from these two examples – take the time to understand what your customer is actually buying (vs. what you are selling) and actually cares about. And while the difference between what you are selling and what the customer is buying is sometimes subtle, it can be the difference between building a big business or completely failing.

Knowing Your What

So how do we figure out the what? It starts with another series of questions that you pose to real prospects and customers. Here is an example of some of those questions (we'll get more in-depth on this topic in the “Putting W3 Together” section). What are they buying? What product/feature is the customer buying? What problem are you solving for that buyer? How will they buy your product? How will they pay for your product?

Let's start at the beginning—meaning the day you were sitting at the coffee shop and had that aha moment that it was time for you to start a company and you had just the right idea. This was the moment when you decided to leave the security of your current life and jump in, feet first, to build a huge company.

This may sound corny but close your eyes and take 20 seconds to try and remember the exact feelings you had that day. Remember the problem you identified and remember how excited you were when you realized you were uniquely equipped to solve that problem and build the next unicorn. Now write down the product you want to sell followed by a list of three to five things you believe your product solves for your customer. Next look at each one of those items and write down one to three questions for each that you can pose to potential customers from your who list.

However, before you go do that, try to answer them yourself. Write down your answers so you can refer back to them and see where you were right or wrong. There are two reasons to do this: first, it will provide a history for you of how your product and thinking is shaped and evolves based on what your customer is actually buying (and why, which we'll get to in the next section). And second, if you pay close attention, you can also learn about the way in which your customer set does business by listening to both the answers and the language that your customers use. This data will become important further on when we dig into building your sales process, which is why I want you to record it.

If you are like me, you may have started this work as you were reading this section; that's great, but don't worry if you didn't, we'll get deeper into it in the exercises in the “Putting W3 Together” section. More important to take away from this section is an understanding and belief that you need to understand what your customer is actually buying from you in order for you to build the correct product. Now that you understand the difference between what you are selling and what your customer is buying, we can move on to the why.

Why Is Your Customer Buying It?

If I asked you that question, you'd likely give me either your problem statement or mission statement. For most founders, why their customer is buying their product is the entire reason they are building their company. But there are actually three questions that need to be answered here:

- Why you believe they will buy your product

- Why they say they (may) buy your product

- Why they really buy your product

Why You Believe They Will Buy Your Product

This is the entire reason you exist, to solve a problem or gap for your end user. Likely this is the problem statement in your sales and investor deck. This is also what you answer when people ask you what your company does. Great! This is exactly where you should start. Why you believe your customer will buy your product is exactly the flag in the ground you need to get started; just keep in mind that it is simply a starting point and without understanding the other whys, it's nearly impossible to build a really big and scaled business.

In order to help you understand the next two whys, we're going to start with an example. At Business.com, we believed our customers bought our product to reach more of their target customers: small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs). This was our core message and how we talked about the value of Business.com for our customers, and while on the surface we were right, there was more motivation that our customers needed before they would actually spend money with us. This is where the next two whys come into play.

Why Prospective Customers Say They (May) Buy Your Product

Think about this as the actual problem you are solving for your customer on the business level. When this aligns perfectly with your first why, you are in a great place, but they actually don't need to be perfectly aligned as long as you understand this second why and can address it. Remember in the case of Business.com, we believed our customers bought our product to reach more of their target customers. While this is true, that meant something different to each of our customers. For some, that meant actually driving direct sales (i.e. the expectation was that when a user left Business.com and went to a website a transaction would take place). Those customers measured us on direct transactions, also known as sales of their product.

Other customers of ours bought Business.com because they were buying leads (or prospective customers for their business). And while ultimately they were looking to drive more sales, their expectation wasn't that a transaction would take place immediately. Instead they would have their own system to nurture leads that came from Business.com and their own process to eventually turn some quantity of leads into sales.

And we even had a third kind of buyer who was buying Business.com for measured awareness. They didn't expect or track transactions from Business.com, but they did track the number of people who were exposed to their company from Business.com.

For us, at Business.com, it was important to understand the business reason why each buyer was buying our product because it gave us insight into their ability to reach their goals and be successful in buying our product, which translated into our ability to acquire long-term happy customers. Over time, what we learned was that the middle group, companies looking to build a lead/nurture list, was the most successful group on Business.com. There is an entirely different book that can likely be written on this topic, but we classified our product and customers by thinking about the stage that their customer is in when they came to Business.com. Those stages are learn, find, and buy. The learn stage meant that someone was on Business.com doing initial research on a product and trying to collect information so they would be able to make an informed decision down the road. We learned early on that “learning” was not our main role. That doesn't mean that millions of users didn't come to Business.com monthly to learn about a product they may buy in the future; in fact, they did. And we had a very specific user experience designed for them. However, our experience showed that when our customer was looking to primarily drive awareness they, for several different reasons, were not our best customers and often had higher churn.

“Buy” is the first why I listed above, which means there was an expectation of a transaction once a user left Business.com and went to our customer's website. While we were able to drive some level of transactions, what we learned was that for B2B sales (and specially SMB sales), it was very rare for a user to make many purchases off any website and often they wanted to buy from a person (either because of product type or the cost of the merchandise). And while there were some products (i.e. toner cartridges) for which we were able to drive high volumes of transactions, buy wasn't really our sweet spot either.

That brings us to the middle of the funnel: find. This is the spot between a user doing research and actually making a purchase where they are trying to find a specific vendor (or vendors) to buy from. This is where Business.com really shined for our customers. And once we understood this, we were much better positioned to find and acquire high-value customers. Understanding this why gave us the ability to narrow our core target base by asking a simple question in the sales process around what our prospects hoped to achieve by working with us. We would tease out of the conversation whether their expectation was learn, find, or buy and emphasize selling to customers who fell into the “find” category. This understanding also gave us the ability to do things within our product to help drive more qualified leads to our customers. (“Qualified leads” means a buyer who actually has intent to make a purchase.) We were able to shape the product with layout, product descriptions, and a user experience that made it clear to our user what they were supposed to do and how to do it. Likewise having this understanding with our customers gave us a clear pathway to understanding how they would measure success using Business.com, which in turn lets us become their partner in achieving that success.

I realize there is a lot to absorb in the last few paragraphs, so let's pause and I'll state it in a different way. Our customers were focused on the find-stage. If we were focused on providing learning-stage users to them, then we would likely be focused on quantity rather than on quality of users. We would have designed our product to focus on attracting as many people to their site as possible, with little regard for whether they would ever buy. Likewise, if we were focused on the buying-stage users, we might have gotten very good at finding users to transact on our customers websites, but we would not have been able to work with any business that had a more complex or higher value product. By focusing on find, we were able to strike the perfect balance between delivering quantity while being held to a quality standard. And for this reason, when we had the right customer type, we had very low churn. At the time I left Business.com, we had below 1% customer churn and net positive revenue churn.

Why They Really Buy Your Product

This brings us to the last why—why your customer really buys your product. This is often the hardest one to figure out, but often the one that will actually drive the close of your sales. This has to do with your actual buyer. Let's step back and recap on the first two whys first. Our first why is your belief in the problem you believe you are solving for your potential customer. In the case of Business.com, that was to sell more of their products or services and increase their revenue. Our second why is why they say they (may) buy your product. This is the business reason. In the case of Business com, it was because our customers were looking at our users as people who could either learn, find, or buy their products through Business.com. Conventional wisdom might say that you have all the information you need but, as discussed earlier, there is one more crucial why to be answered: why they really buy your product. This why has to do with the motivation of your buyer.

Your buyer could be motivated for any number of reasons, from their boss telling them they had to buy your product or to help them save time or because they are driving toward a specific metric as part of their job. When you understand this why, you have unlocked the final piece in helping secure a sale and a happy customer, because along with focusing on the success of their business you can also help focus on their personal success. I get more into that at the end of the “Why” section, but for now let's dig deeper into understanding why your customer really buys your product.

Think about your own job for a minute. Whether you are a founder/CEO of an early stage company, head of sales, or fill some other role in your company, think about your own buying habits. To illustrate my point, let's imagine that I'm selling Business.com as a service to an established company that sells credit card processors. For this example, let's also assume that this marketer is good at their job, highly regarded within their company, and hitting all their goals. Before buying our product, there is no way for them to tell how we might affect their goal attainment, and therefore no real motivation for them to go out on a limb to buy from us (too). In this scenario, picture that we have nailed the first two whys perfectly, yet we really do not know what the third why is yet, why our customer would actually buy from us.

It's at this point that we need to dig deeper to understand our buyer's personal motivation to become a customer. Can we save them time? Money? Can we help them meet or exceed their goals? Can we help them satisfy their boss? Are you starting to see why this why is so important? We are all very busy and in order to cross the final threshold into making a sale, it's imperative that we understand the underlying motivation of our buyer. And there is no substitute here for just asking the question. Personally I like to be very direct about it and will say something like, “we've agreed that Business.com can bring you more qualified leads, but how does this help you in your job? Does it make things easier or harder and let's talk about it.” This simple line of questioning opens up an entirely new conversation around personal motivation to become a customer and it gives you, the seller, the ability to set up this customer to be successful.

Measuring Your—and Your Customer's—Why

The final thing I want to say about why is that, although knowing about it is crucial, knowing how to measure it is imperative.

Arguably the concepts of measuring and metrics deserve their own section in this book, but I'm intentionally introducing the topic now to alert you to its importance. Whatever it is that we're talking about in W3 or Sell More Faster or your business, understanding what should be measured, how to measure it, and how that affects our ability to build a big business will always be an underlying factor. And that is the same for all of our (potential) customers. We'll directly (and indirectly) get into measuring who and what throughout the book as we talk about building prospect lists and iterating the product. But we're going to talk about measuring why here. Why, you ask? Because if we do not deeply understand how our prospective customer will measure their success, then we have no real way to know if our product is working, what about it is working, or why it's working. We'll also have no way to predict how we should evolve our product or service, pitch it, or even who our customers should be. And, worst of all, we'll have no way to predict churn or why we are losing customers.

Getting to the core of how our customers measure why is fundamental to acquiring high value, low-churn customers, and building a big business. Let's take a look, using the same example from above, with the marketer who sells credit card processors. For this example, we'll assume that we've checked the first two why boxes and know that this is a great prospective customer. We have a conversation with our buyer and we learn two things. The first is that our buyer will be measuring our success by using Google Analytics and will have an expectation of a 10% close rate within 60 days with an average customer value of $200. The second thing we learn is that our buyer's supervisor hasn't typically believed that search marketing, outside of Google, was very effective, even though our buyer believes they are missing a lot of opportunity. We now understand that our buyer, while maybe a believer, has a heightened motivation around quality and likely less room for error because she will have to put her neck out in order to test with something other than Google, but also that if we're able to help drive new and incremental sales, then we will help our buyer build credibility internally, which will help her career. Because our buyer has been clear both about the metrics she is shooting for and her own motivations, we are able to work with her to reach those goals.

In contrast, and as a way to help understand the importance of understanding how your customer will measure and be measured for success, take the same buyer with the same method of measuring business success (10%/60 days/$200 average order), but in this case our buyer is considered the expert by their supervisor and our buyer has no external motivation to drive additional net new sales (meaning that she is hitting her expressed goals from her supervisor with no additional incentive to go beyond these goals). This happens a lot and is often the biggest reason why sales don't close. Assuming that you still have the first two whys nailed, you have to dig deeper to see what might motivate this buyer. It could be that something in the product helps them save time or money. Or it could be that your product doesn't match with this buyer's personal why. That doesn't mean this company can't be a customer but it does likely mean that you do not have the right buyer within that company. You may need to go to their supervisor because their motivations are more aligned or you may need to find a completely new buyer within the organization.

Okay, we're going to pause for a second. I just gave you a ton of information on why. I know it's a lot to process at once. That's okay; a lot of this probably makes perfect sense already and some of it you may just need to experience firsthand. In any case, I'm going to boil down why here for you, which is to say that understanding why a prospect becomes a customer, while complex, is the final but most important part of W3. It's the thing that binds the who and the what together and gives you the ability to define your ICP (ideal customer profile, remember that) and the confidence to articulate it to staff, investors, and customers.

Putting W3 Together

For me, being able to define W3 is literally the basis for every conversation with every founder I work with because, while we are discussing it here in terms of selling more faster, W3 touches upon so much more. As discussed earlier, understanding your W3 helps shape your product, pitch, marketing, the technology you build, and every aspect of your business. It also gives you the ability to articulate your business to your staff in a way that will connect and align the roles they fulfill in your company. Likewise, investors will be able to paint a clearer picture of what they are investing in and how your business will potentially grow (and, more important, the process you will use to figure out how to build a big business). Furthermore, it will make it clear to your customers why you exist, making it easier to align with their needs and work with them for the long term.

In order to help you on your journey, most sections in this book end with an exercise so that you have a structured framework and put pen to paper. After each exercise there will be an example with the answers filled in, so that you can refer to them as you go along. Don't hesitate to flip back and forth to my example; just keep in mind that the answers from the example are specific to that business and may not directly apply to yours. The other thing to keep in mind here is that it's okay to guess when you don't know—guessing will be your hypothesis of what you currently believe. Take special care to mark what you know as fact versus what matches your hypothesis, so that you can test your beliefs in the quest to improve your W3.