chapter one

understand the context

A little planning can go a long way and lead to more concise and effective communications. In our workshops, I find that we allocate an increasing amount of time and discussion on the very first lesson we cover, which focuses on context. People come in thinking they want data visualization best practices and are surprised by the amount of time we spend on—and that they want to spend on—topics related more generally to how we plan for our communications. By thinking about our audience, message, and components of content up front (and getting feedback at this early stage), we put ourselves in a better position for creating graphs, presentations or other data-backed materials that will meet our audience’s needs and our own.

The exercises in this chapter focus primarily on three important aspects of the planning process:

- Considering our audience: identifying who they are, what they care about, and how we can better get to know them and design our communications with them in mind.

- Crafting and refining our main message: the Big Idea was introduced briefly in SWD; here, we’ll undertake a number of guided and independent exercises to better understand and practice this important concept.

- Planning content: storyboarding is another concept that was introduced in SWD—we’ll look at a number of additional examples and exercises related to what we include and how we organize it.

Let’s practice understanding the context!

First, we’ll review the main lessons from SWD Chapter 1.

Exercise 1.1: get to know your audience

Who is my audience? What do they care about? These may seem like obvious questions to ask ourselves when we step back and think about it, but too often we completely skip this step. Getting to know our audience and understanding their needs and what drives them is an important early part of the process for successfully communicating with data.

Let’s examine what this looks like in the wild and how we can get to know a new audience.

Imagine you work as a People Analyst (a data analyst within the Human Resources, or HR, function) at a medium-sized company. A new head of HR has just joined the organization (she is now your boss’s boss). You’ve been asked to pull together an overview with data to help the freshly hired head of HR get up to speed with the different parts of the business from a people standpoint. This will include things like interview and hiring metrics, a headcount review across different parts of the organization, and attrition data (how many are leaving and why they are leaving). Some of your colleagues in other groups within HR have already had meet-and-greets with the new leader and given their respective synopses. Your direct manager recently had lunch with the new head of HR.

How could you get to better know your audience (the new head of HR) in this circumstance? List three things you could do to understand your audience, what she cares about, and how to best address her needs. Be specific in terms of what questions you would seek to answer. Get out your pen and paper and physically write down your responses.

Solution 1.1: get to know your audience

Since this isn’t likely a case where we can ask our audience directly what she cares about, we’ll need to get a little creative. Here are three things I could do to set myself up for success when it comes to better understanding my audience and what matters to her most:

- Set up time to get a debrief from colleagues who have already met with the new leader. Talk to those who have had conversations with the new head of HR. How did those discussions go? Do they have any insight on this new leader’s priorities or points of interest? Is there anything that didn’t go well from which you can learn and adapt?

- Talk to my manager to get insight. My manager has lunched with the new leader: what insight did he get about potential first points of focus? I also need to understand what my manager sees as important to focus on in this initial meeting.

- Use my understanding of the data and context plus some thoughtful design to structure the document. Given that I’ve been working in this space for a while, I have a big picture understanding of the different main topics that someone new to our organization will assumably be interested in and the data we can use to inform. If I’m strategic in how I structure the document, I can make it easy to navigate and meet a wide variety of potential needs. I can provide an overview with the high level takeaways up front. Then I can organize the rest of the document by topic so the new leader can quickly turn to and get more detail on the areas that most interest her.

Exercise 1.2: narrow your audience

There is tremendous value in having a specific audience in mind when we communicate. Yet, often, we find ourselves facing a wide or mixed audience. By trying to meet the needs of many, we don’t meet any specific need as directly or effectively as we could if we narrowed our focus and target audience. This doesn’t mean that we don’t still communicate to a mixed audience, but having a specific audience in mind first and foremost means we put ourselves in a better position to meet that core audience’s needs.

Let’s practice the process of narrowing for purposes of communicating. We’ll start by casting a wide net and then employ various strategies to focus from there. Work your way through the questions and write out how you would address them. Then read the following pages to better understand various strategies for narrowing our audience.

You work at a national clothing retailer. You’ve conducted a survey asking your customers and the customers of your competitors about various elements related to back-to-school shopping. You’ve analyzed the data. You’ve found there are some areas where your company is performing well, and also some other areas of opportunity. You’re nearing the point of communicating your findings.

QUESTION 1: There are a lot of different groups of people (at your company and potentially beyond) who could be interested in this data. Who might care how your stores performed in the recent back-to-school shopping season? Cast as wide of a net as possible. How many different audiences can you come up with who might be interested in the survey data you’ve analyzed? Make a list!

QUESTION 2: Let’s get more specific. You’ve analyzed the survey data and found that there are differences in service satisfaction reported by your customers across the various stores. Which potential audiences would care about this? Again, list them. Does this make your list of potential audiences longer or shorter than it was originally? Did you add any additional potential audiences in light of this new information?

QUESTION 3: Let’s take it a step further. You’ve found there are differences in satisfaction across stores. Your analysis reveals items related to sales associates as the main driver of dissatisfaction. You’ve looked into several potential courses of action to address this and determined that you’d like to recommend rolling out sales associate training as a way to improve and bring consistency to service levels across your stores. Now who might your audience be? Who cares about this data? List your primary audiences. If you had to narrow to a specific decision maker in this instance, who would that be?

Solution 1.2: narrow your audience

QUESTION 1: There are many different audiences who might care about the back-to-school shopping data. Here are some that I’ve come up with (likely not a comprehensive list):

- Senior leadership

- Buyers

- Merchandisers

- Marketing

- Store managers

- Sales associates

- Customer service people

- Competitors

- Customers

Eventually, everyone in the world may care about this data! Which is great, but not so helpful when it comes to narrowing our audience for the purpose of communicating. There are a number of ways we can narrow our audience: by being clear on our findings, specific on the recommended action, and focused on the given point in time and decision maker. The answers to the remaining questions will illustrate how we can focus in these ways to have a specific audience in mind when we communicate.

QUESTION 2: If service levels are inconsistent across stores, the following audiences are likely to care most:

- Senior leadership

- Store managers

- Sales associates

- Customer service people

QUESTION 3: We want to roll out training—that sparks some questions for me. Who will create and deliver the training? How much will it cost? With this additional clarity, some new audiences have entered the mix:

- Senior leadership

- HR

- Finance

- Store managers

- Sales associates

- Customer service people

The preceding list may all eventually be audiences for this information. We’ve noted inconsistencies with service levels and need to conduct training. HR will have to weigh in on whether we can meet this need internally or if it will require us to bring in external partners to develop or deliver training. Finance controls the budget and we’ll have to figure out where to get the money to pay for this. Store managers will need to buy-in so they are willing to have their employees spend time attending the training. The sales associates and customer service people will have to be convinced that their behavior needs to change so that they will take the training seriously and provide consistent high quality service to customers.

But not all of these groups are immediate audiences. Some of the communications will take place downstream.

To narrow further, I can reflect on where we are at in time: today. Before we can do any of the above, we need approval that rolling out training is the right course of action. A decision needs to be made, so another way of narrowing my audience is to be clear on timing as well as who the decision maker (or set of decision makers) is within the broader audience. In this instance, I might assume the ultimate decision maker—the person who will either say, “yes, I’m willing to devote the resources; let’s do this,” or “no, not an issue; let’s continue to do things as we have been”—is a specific person on the leadership team: the head of retail sales.

In this example, we have employed a number of different ways to narrow our target audience for the purpose of the communication. We narrowed by:

- Being specific about what we learned through the data,

- Being clear on the action we are recommending,

- Acknowledging what point we’re at in time (what needs to happen now), and

- Identifying a specific decision maker.

Consider how you can use these same tactics to narrow your audience in your own work. Exercise 1.18 in practice at work will help you do just that. But before we get there, let’s continue to practice together and turn our attention to a useful resource: the Big Idea worksheet.

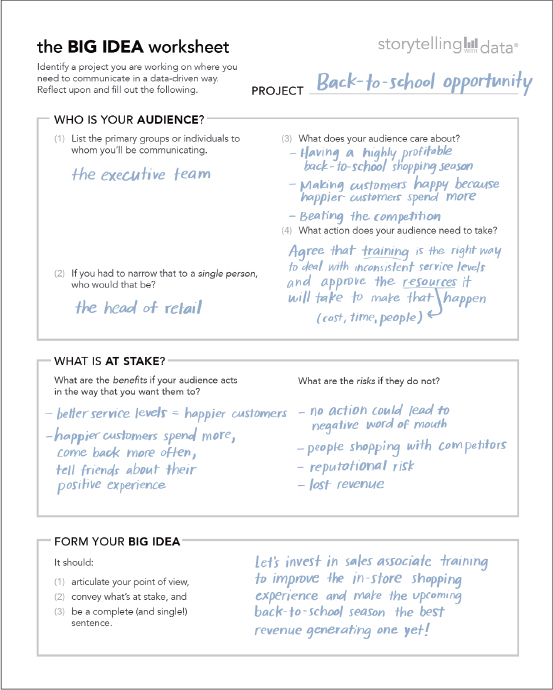

Exercise 1.3: complete the Big Idea worksheet

The Big Idea is a concept that can help us get clear and succinct on the main message we want to get across to our audience. The Big Idea (originally introduced by Nancy Duarte in Resonate, 2010) should (1) articulate your unique point of view, (2) convey what’s at stake, and (3) be a complete sentence. Taking the time to craft this up front helps us get clarity and concision on the overall idea we need to communicate to our audience, making it easier and more streamlined to plan content to get this key message across.

In storytelling with data workshops, we use the Big Idea worksheet to help craft our Big Idea. Attendees commonly express how unexpectedly helpful they find this simple activity. We’ll do a few related exercises so you can practice and see examples of the Big Idea worksheet in action. Let’s start by continuing with the example we just worked through for narrowing our audience. As a reminder, the basic context follows.

You work at a national clothing retailer. You’ve conducted a survey asking your customers and the customers of your competitors about various elements related to back-to-school shopping. You’ve analyzed the data. You’ve found there are some areas where your company is performing well, as well as some areas of opportunity. In particular, there are inconsistencies in service levels across stores. Together with your team, you’ve explored some different potential courses of action for dealing with this and would like to recommend solving through sales associate training. You need agreement that this is the right course of action and approval for the resources (cost, time, people) it will take to develop and deliver this training.

Think back to the audience we narrowed to in Exercise 1.2: the head of retail. Work your way through the Big Idea worksheet on the following page for this scenario. Make assumptions as needed for the purpose of the exercise.

Solution 1.3: complete the Big Idea worksheet

Exercise 1.4: refine & reframe

Consider both your Big Idea from Exercise 1.3 and the one I came up with in Solution 1.3. Answer the following questions.

QUESTION 1: Compare and contrast. Are there common points where they are similar? How are they different? Which do you find to be more effective and why?

QUESTION 2: How did you frame? Reflect on the Big Idea you originally crafted. Did you frame it positively or negatively? What is the benefit or risk in your Big Idea? How could you reframe it to be the opposite?

QUESTION 3: How did I frame? Revisit the Big Idea articulated in Solution 1.3. Is it framed positively or negatively? What is the benefit or risk in this Big Idea? Again, how could you reframe it to be the opposite? How else might you refine?

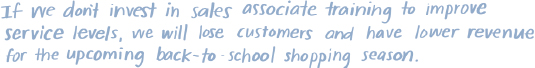

Solution 1.4: refine & reframe

Given that I don’t have your Big Idea as I write this, I’ll focus on Question 3, which poses some questions about mine. Here it is again for reference:

How did I frame? What is the benefit or risk? This is currently framed positively, focusing on the benefit of the revenue we stand to gain by investing in sales associate training.

How could you reframe it to be the opposite? I could reframe negatively a couple of different ways. One simple way would be to focus on the same thing at stake—revenue—but change to emphasize the loss that could result from not taking action.

But revenue isn’t the only thing at stake. What if I know that my audience is highly motivated by beating the competition? Then I could try something like this:

How else can we refine this Big Idea? There’s no single right answer. There are a number of different potential benefits (more satisfied customers, greater revenue, beating the competition) and risks (unhappy customers, lower revenue, losing to competition, negative word of mouth, reputational damage). What we assume our audience cares most about will influence how we frame and what we focus on in our Big Idea.

In a real-life scenario, we’d want to know as much about our audience as we can to make smart assumptions. Check out Exercise 1.17 in practice at work for guidance on getting to know your audience. Next, let’s look at another Big Idea worksheet.

Exercise 1.5: complete another Big Idea worksheet

Let’s do another practice run with the Big Idea worksheet.

Imagine you volunteer for your local pet shelter, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to improve the quality of animal life through veterinary care, adoptions, and public education. You help organize monthly pet adoption events, which feed into the organization’s broader goal of increasing permanent adoptions of pets by 20% this year.

Traditionally, these monthly events have been held in outdoor spaces in your community (parks and greenways) on Saturday mornings. However, last month’s event was different. Due to poor weather, the event was relocated indoors to a local pet supply retailer. Surprisingly, after the event, you observed something interesting: nearly twice as many pets were adopted compared to previous months.

You have some initial ideas about the reasons for this increase and think there’s value in holding more adoption events at this retailer. You’d like to conduct a pilot program over the next three months to see if the results help confirm your beliefs. To implement this pilot program, you’ll need additional support from the pet shelter’s marketing volunteers to publicize the events. You’ve estimated the monthly costs to be $500 for printing and three hours of a marketing volunteer’s time. You want to ask the event committee to approve the pilot program at next month’s meeting and are planning your communication.

Complete the Big Idea worksheet on the following page for this scenario, making assumptions as necessary for the purpose of the exercise.

Solution 1.5: complete another Big Idea worksheet

The following illustrates one way to complete the Big Idea worksheet for this scenario.

Exercise 1.6: critique the Big Idea

Being able to give good feedback on the Big Idea is important both when we work with others, as well as for critiquing and refining our own work. Let’s practice giving feedback on the Big Idea.

Suppose you work for a health care center that has been analyzing recent vaccine rates. Your colleague has been focusing on progress and opportunities related to flu vaccines. He has crafted the following Big Idea for the update he is preparing and has asked for your feedback.

While flu vaccination rates have improved since last year, we need to increase the rate in our area by 2% to hit the national average.

With this Big Idea in mind, write a few sentences outlining your response to the following.

QUESTION 1: What questions might you ask your colleague?

QUESTION 2: What feedback would you provide on his Big Idea?

Solution 1.6: critique the Big Idea

QUESTION 1: The immediate questions I’d have for my colleague would be about their audience: who are they? What do they care about?

QUESTION 2: In terms of giving specific feedback on the Big Idea, let’s think back to the components of the Big Idea—it should (1) articulate your point of view, (2) convey what’s at stake, and (3) be a complete (and single!) sentence. Let’s consider each of these in light of my colleague’s Big Idea.

- Articulate your point of view. The point of view is that vaccination rates are low compared to the national average and need to be increased.

- Convey what’s at stake. This isn’t clear to me currently. I’m going to want to ask some targeted questions to better understand what is at stake for the audience.

- Be a complete (and single!) sentence. Good job on this front. It’s often difficult to summarize our point in a single sentence. If anything, we have room to possibly add a little more to the sentence to make it meatier and more clearly convey what is at stake.

In general, the Big Idea in its current form gives me the what (increase vaccination rates), but not the why (it also doesn’t get into the how, though there’s only so much we can fit into a sentence, and this piece can come into play through the supporting content).

You could argue that the why is because we’re lower than the national average, but this doesn’t feel compelling enough. Is my audience going to be motivated by a national average comparison? Is that even the right goal? Is it aggressive enough? Too aggressive? Can we get more specific by thinking through what will be most motivating for the audience?

It’s clear my colleague believes that we should increase flu vaccination rates. But let’s consider why our audience should care. What does this mean for them? Are they motivated by competition—maybe we’re lower than that other medical center across town, or our area is low compared to the state, or perhaps the national comparison is the right one but can be articulated in a more motivating way? Or maybe my audience is driven by generally doing good—we could get into patient advantages or highlight general community well-being benefits that would be well served by increasing vaccination rates. If we think about positive versus negative framing—which will be best for this scenario and audience?

The conversation I have with my colleague will cause him to explain his thought process, what he knows about his audience, and what assumptions he’s making. The dialogue we have will help him both refine his Big Idea as well as be better prepared to talk through this with his ultimate audience. Success!

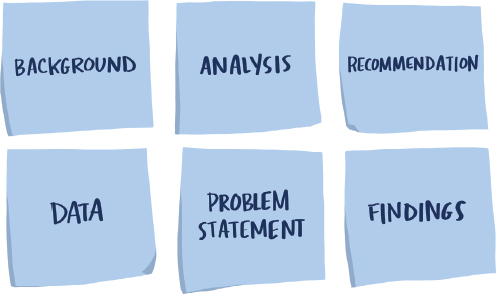

Exercise 1.7: storyboard!

I sometimes feel like a broken record because I say this so frequently: storyboarding is the most important thing you can do up front as part of the planning process to reduce iterations down the road and create better targeted materials. A storyboard is a visual outline of your content, created in a low-tech manner (before you create any actual content). My preferred tool for storyboarding is a stack of sticky notes, which are both small—forcing us to be concise in our ideas—and lend themselves to being easily rearranged to explore different narrative flows. I typically storyboard in three distinct steps: brainstorming, editing, and seeking and incorporating feedback.

We’ll do a couple of practice storyboarding runs so you can both get a feel for it and see illustrative approaches. Let’s start with an example you should be familiar with now (we’ve seen it previously in Exercises 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4). As a reminder, the basic context follows.

You work at a national clothing retailer. You’ve conducted a survey asking your customers and the customers of your competitors about various elements related to back-to-school shopping. You’ve analyzed the data. You’ve found there are some areas where your company is performing well, as well as some areas of opportunity. In particular, there are inconsistencies in service across stores. Together with your team, you’ve explored different potential courses of action for dealing with this and would like to recommend solving through sales associate training. You need agreement that this is the right course of action and approval for the resources (cost, time, people) it will take to develop and deliver this training.

Look back to the Big Idea that you created in Exercise 1.3 (or if you didn’t create one, select one of the Big Ideas from Solutions 1.3 or 1.4). Complete the following steps with a specific Big Idea in mind.

STEP 1: Brainstorm! What pieces of content may you want to include in your communication? Get a blank piece of paper or a stack of stickies and start writing down ideas. Aim for a list of at least 20.

STEP 2: Edit. Take a step back. You’ve come up with a ton of ideas. How could you arrange these so that they make sense to someone else? Where can you combine? What ideas did you write down that aren’t essential and can be discarded? When and how will you use data? At what point will you introduce your Big Idea? Create your storyboard or the outline for your communication. (I highly recommend using sticky notes for this part of the process!)

STEP 3: Get feedback. Grab a partner and have them complete this exercise, then get together and talk about it. How are your storyboards similar? Where do they differ? If you don’t have a partner who has completed the exercise, you can still talk someone through your plan. What changes would you make to your storyboard after talking through it with someone else? Did you learn anything interesting through this process?

Solution 1.7: storyboard!

Looking back to Exercise 1.3, my Big Idea was the following:

I’ll keep this in mind as I work through the storyboarding steps.

STEP 1: Below is my initial list of potential topics/pieces of content to include from my brainstorming process.

STEP 2: Figure 1.7 illustrates how I might curate the preceding list into a storyboard.

Figure 1.7 Back-to-school shopping: a potential storyboard

Does Figure 1.7 illustrate the “right” answer? No. Will you always end up with a perfect grid of sticky notes like this? Not likely. Are there things you would have done differently? Probably. Are there additional changes that I would make to this? Yes. We’ll revisit this scenario again a little later to explore how we can further refine this storyboard. But for now, take this as one illustrative storyboard and let’s turn our attention to Step 3.

STEP 3: What feedback do you have for me on this storyboard? How is yours similar? Where does it differ? Consider how you can apply this approach to a current project you face. Exercises 1.23, 1.24, and 1.25 in practice at work will help you do just that. Before we get there, let’s do some additional guided practice storyboarding.

Exercise 1.8: storyboard (again!)

For this exercise, we’ll create a storyboard using the pet adoptions pilot program we introduced in Exercise 1.5. As a reminder, the background is as follows:

Imagine you volunteer for your local pet shelter, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to improve the quality of animal life through veterinary care, adoptions, and public education. You help organize monthly pet adoption events, which feed into the organization’s broader goal of increasing permanent adoptions of pets by 20% this year.

Traditionally, these monthly events have been held in outdoor spaces in your community (parks and greenways) on Saturday mornings. However, last month’s event was different. Due to poor weather, the event was relocated indoors to a local pet supply retailer. Surprisingly, after the event, you observed something interesting: nearly twice as many pets were adopted this month compared to previous months.

You have some initial ideas about the reasons for this increase and think there’s value in holding more adoption events at this retailer. You’d like to conduct a pilot program over the next three months to see if these results help confirm your beliefs. To implement this pilot program, you’ll need additional support from the pet shelter’s marketing volunteers to publicize the events. You’ve estimated the monthly costs to be $500 for printing and three hours of a marketing volunteer’s time. You want to ask the event committee to approve the pilot program at next month’s meeting and are planning your communication.

Look back to the Big Idea that you created in Exercise 1.5 (or if you didn’t create one, revisit the Big Idea from Solution 1.5). Complete the following steps with this specific Big Idea in mind.

STEP 1: Brainstorm! In this first step, brainstorm what details might be necessary to include in the eventual presentation. Get a blank piece of paper or a stack of stickies and start writing down ideas. Aim for a list of at least 20. To aid in your brainstorming process, ask yourself: has the organization ever tried a pilot program before? Will the events committee need to understand the risks and benefits of this program? Are they likely to respond favorably or unfavorably? Do you have historical data on the number of adoptions from community spaces? Are you aware whether other shelters have successfully tried this? How will you measure and assess the results from the three-month pilot? What does success look like?

STEP 2: Edit. Examine all the ideas you generated in Step 1. Next, let’s plan how to put them to use. Determine which pieces of potential content are essential and which can be discarded. Create your storyboard or the outline for the presentation. To aid in the editing and arranging process, ask yourself: having identified your audience’s likely response in Step 1, will you start with the Big Idea or build up to it? How familiar is your audience with the recent success—will you need to communicate this context or is it already well known? Which other details are new to the audience and may require more time or data behind them? Will your audience be accepting of your proposal or will you need to convince them? How can you best do that?

STEP 3: Get feedback. Grab a partner and have them complete this exercise, then get together and talk about it. How are your storyboards similar? Where do they differ? If you don’t have a partner who has completed the exercise, you can still talk someone through your plan. What changes would you make to your storyboard after talking through it with someone else? Did you learn anything interesting through this process?

Solution 1.8: storyboard (again!)

Looking back to Exercise 1.5, my Big Idea was the following:

I’ll keep this in mind as I work through the storyboarding steps.

STEP 1: Following is my initial list of potential topics to include from my brainstorming process.

STEP 2: Figure 1.8 illustrates how I could curate the preceding list into a storyboard.

Figure 1.8 Pet adoption pilot program: a potential storyboard

STEP 3: What feedback do you have for me on this storyboard? How is yours similar? Where does it differ? How can you apply this approach to a current project you face? Refer to exercises 1.23, 1.24, and 1.25 for guidance on storyboarding at work.

You’ve practiced narrowing your audiences, crafting your Big Idea, and storyboarding with me. Next, you’ll find more low-risk practice for you to tackle on your own.

Exercise 1.9: get to know your audience

Let’s say you work at a consulting company. You have a new client, the director of marketing at a prominent pet food manufacturer. You are one level removed from your audience: rather than interfacing with them directly, you provide analysis and reports to your boss, who presents this work to the client, discusses it with them, and then communicates any feedback or additional needs to you.

How can you better get to know your audience in this case? List three things you could do to better understand your audience and what they care about. How does having the intermediate audience of your manager potentially complicate things? How might you use this to your advantage? What other considerations do you need to make in order to be successful in this scenario?

Write a paragraph or two to answer these questions.

Exercise 1.10: narrow your audience

Next, you’ll practice narrowing the audience. Read the following, then work your way through the various questions posed to determine how you can narrow your audience for purposes of communicating given different assumptions.

Imagine you work for a regional medical group. You and several colleagues have just wrapped up an evaluation of Suppliers A, B, C, and D for the XYZ Products category. Your analysis examined historical costs by facility, patient and physician satisfaction, and cost projections going forward. You are in the process of creating a presentation deck with this information.

QUESTION 1: There are a lot of different groups of people (at your company and potentially beyond) who may be interested in this data. Who can you think of who is apt to care how the various suppliers compare when it comes to historical usage, patient and physician satisfaction, and cost projections? Cast as wide of a net as possible. How many different audiences can you come up with who might be interested in this information? List them!

QUESTION 2: Let’s get more specific. The data shows that historical usage has varied a lot by medical facility, with some using primarily Supplier B and others using primarily Supplier D (and only limited historical use of Suppliers A and C). You’ve also found that satisfaction is highest across the board for Supplier B. Which potential audiences might care about this? Again, list them. Does this make your list of potential audiences longer or shorter than it was originally? Did you add any additional potential audiences in light of this new information?

QUESTION 3: Time to take it a step further. You’ve analyzed all of the data and realized there are significant cost savings in going with a single or dual supplier contract. However, either of these will mean changes for some medical centers relative to their historical supplier usage. You need a decision on how to best move forward strategically in this space. Now who might your audience be? Who cares about this data? List your primary audiences. If you had to narrow to a specific decision maker, who would that be?

Exercise 1.11: let’s reframe

One component of the Big Idea is what is at stake for your audience. As we’ve discussed, this can be framed either in terms of benefits (what does your audience stand to gain if they act in the way you recommend?) or in terms of risks (what does your audience stand to lose if they don’t act accordingly?). It is often useful to explore both the positive and negative framing as you think through which might work best for your specific situation.

Consider the following Big Ideas and answer the accompanying questions to practice identifying and reworking how each is framed.

BIG IDEA 1: We should increase incentives to complete our email survey so we can collect better quality data and gain a robust understanding of our customers’ pain points.

- Is this Big Idea currently positively or negatively framed?

- What is the benefit or risk in this Big Idea?

- How could you reframe it to be the opposite?

BIG IDEA 2: We stand to miss our earnings per share target if we don’t reallocate resources to support emerging markets now that revenue from our traditional line of business has plateaued.

- Is this Big Idea currently positively or negatively framed?

- What is the benefit or risk in this Big Idea?

- How could you reframe it to be the opposite?

BIG IDEA 3: Last quarter’s digital marketing campaign resulted in the traffic and sales increases we expected: we should maintain current spend levels to achieve this year’s sales goal.

- Is this Big Idea currently positively or negatively framed?

- What is the benefit or risk in this Big Idea?

- How could you reframe it to be the opposite?

Exercise 1.12: what’s the Big Idea?

We’ve undertaken a number of exercises to get you comfortable working your way through the Big Idea worksheet and also seeing potential solutions (Exercises 1.3 and 1.5). These next couple of exercises are similar—we pose a scenario and ask you to complete the Big Idea worksheet—but there’s no illustrative answer. Rather, it’s up to you to critique and refine what you’ve created.

You are the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) for a national retailer. You are responsible for managing the financial well-being of the company and your duties include analyzing and reporting on the company’s financial strengths and weaknesses and proposing corrective actions. Your team of financial analysts just completed a review of Q1 and have identified that the company is likely to end the fiscal year with a loss of $45 million if operating expenses and sales follow the latest projections.

Because of a recent economic downturn, an increase in sales is unlikely. Therefore, you believe the projected loss can only be mitigated by controlling operating expenses and that management should implement an expense control policy (“expense control initiative ABC”) immediately. You will be reporting the Q1 quarterly results at an upcoming Board of Directors meeting and are planning your communication—a summary of financial results in a PowerPoint deck—that you will present to the board with your recommendation.

Your goals for the presentation are twofold:

- For the Board of Directors to understand the long-term implications of ending the year at a net loss, and

- Get agreement from the daily operating managers (CEO and executives) to implement “expense control initiative ABC” immediately.

Complete the Big Idea worksheet on the following page for this scenario, making assumptions as necessary for the purpose of the exercise.

Exercise 1.13: what’s the Big Idea (this time)?

Let’s do another practice run with the Big Idea worksheet.

Imagine you’re a rising university senior serving on the student government council. One of the council’s goals is to create a positive campus experience by representing the student body to faculty and administrators and electing representatives from each undergraduate class. You’ve served on the council for the past three years and are involved in the planning for this year’s upcoming elections. Last year, student voter turnout for the elections was 30% lower than previous years, indicating lower engagement between the student body and the council. You and a fellow council member completed benchmarking research at other universities and found that universities with the highest voter turnout had the most effective student government council at effecting change. You think there’s opportunity to increase voter turnout at this year’s election by building awareness of the student government council’s mission by launching an advertising campaign to the student body. You have an upcoming meeting with the student body president and finance committee where you will be presenting your recommendation.

Your ultimate goal is a budget of $1,000 for the advertising campaign to increase awareness of why the student body should vote in these elections.

STEP 1: Considering this situation, complete the following Big Idea worksheet, making assumptions as needed for the purpose of this exercise. (Don’t overlook Steps 2 and 3 that follow it.)

STEP 2: Let’s suppose you’ve just learned that your intended audience—the student body president—will not be attending the upcoming meeting due to a scheduling conflict. The vice-president will cover the meeting and approve or deny your budget request. In light of this, answer the following:

- You don’t know the vice-president well. What could you do to get to know her better? Identify one thing you can do immediately—before the meeting—to better understand what she cares about and one thing you’ll do over your tenure on the council to better understand the vice-president’s needs for future communications.

- Revisit your framing of the Big Idea. Did you write it with a positive or negative focus? What may cause you to change to the opposite framing given this new audience?

STEP 3: You’d like to solicit feedback on your Big Idea. You are deciding between two different people from whom to potentially get feedback: (1) your roommate or (2) a fellow council member. Answer the following:

- What would be the advantages or disadvantages of each?

- How do you anticipate the conversations would be different?

- Who would you ultimately choose to solicit feedback from? Why?

Exercise 1.14: how could we arrange this?

There are many ways we can organize the content that we present. Storyboarding allows us to plan the order and consider different arrangements in light of who our audience is and what we hope to achieve when we communicate with them. Look at the potential components of a storyboard in Figure 1.14 (which are presented in no particular order) and answer the following questions.

Figure 1.14 Potential components of a storyboard

QUESTION 1: How would you arrange these components into a storyboard? (What would you start with? What would you end with? How would you order the topics in between?) What drives your decisions on how to order the content?

QUESTION 2: Let’s say you made some assumptions about the data as part of your analysis. At what point in your planned arrangement would you include this? Why is that?

QUESTION 3: Assume you are presenting to a highly technical audience and anticipate there will be a lot of questions and discussion about the data and your analysis. Does this change how you would order your content? Are there additional elements you would include or remove?

QUESTION 4: Imagine you have a solid understanding of the data, but that there is important context that your audience will need to contribute in order for everyone to understand the full picture. Does this affect how you would arrange your content? Where and how would you invite audience input? Would you add or remove any elements?

QUESTION 5: Assume you are presenting to senior leadership. You recognize that you’ll only get a short amount of time (perhaps even shorter than your allotted time slot on the agenda). Does this change how you would order the content? Why or why not?

Exercise 1.15: storyboard!

For this exercise, we’ll create a storyboard using the CFO’s Q1 financial update introduced in Exercise 1.12. As a reminder, the background is as follows:

You are the Chief Financial Officer for a national retailer. You are responsible for managing the financial well-being of the company and your duties include analyzing and reporting on the company’s financial strengths and weaknesses and proposing corrective actions. Your team of financial analysts just completed a review of Q1 and have identified that the company is likely to end the fiscal year with a loss of $45 million if operating expenses and sales follow the latest projections.

Because of a recent economic downturn, an increase in sales is unlikely. Therefore, you believe the projected loss can only be mitigated by controlling operating expenses and that management should implement an expense control policy (“expense control initiative ABC”) immediately. You will be reporting the Q1 quarterly results at an upcoming Board of Directors meeting and are planning your communication—a summary of financial results in a slide deck—that you will present to the board with your recommendation.

Your goals for the presentation are twofold:

- For the Board of Directors to understand the long-term implications of ending the year at a net loss, and

- Get agreement from the daily operating managers (CEO and executives) to implement “expense control initiative ABC” immediately.

Look back to the Big Idea that you created in Exercise 1.12 (if you didn’t create one, spend a few moments doing so now!). Complete the following steps with this Big Idea in mind.

STEP 1: Brainstorm! In this first step, brainstorm what details you might possibly include in the eventual presentation. Get a blank piece of paper or a stack of sticky notes and start writing down ideas. Aim for a list of at least 20. To aid in the brainstorming process, ask yourself a few questions: Is this the first time you’ve introduced your Big Idea to this audience? Do you anticipate they will respond favorably or unfavorably? How frequently have they seen the data you’ll show them—is it a regular update or will you need to allow time to educate them on unfamiliar terms or methodology? Do you anticipate needing to get buy-in from the decision maker on your recommendations? If so, what data points need to be included to help with this process?

STEP 2: Edit. Examine all the ideas you generated in Step 1. Identify which are essential and which can be discarded. Create your storyboard or the outline for the presentation. To aid in the editing and arranging process, ask yourself: having identified your audience’s likely response in Step 1, will you start with the Big Idea or will you lead up to it at the end? Which details has the audience seen regularly that can possibly be discarded? What details are new to the audience and may require more time or data behind them? Are there pieces that can be combined?

STEP 3: Get feedback. Grab a partner and have them complete this exercise, then get together and talk about it. How are your storyboards similar? Where do they differ? If you don’t have a partner who has completed the exercise, you can still talk someone through your plan. What changes would you make to your storyboard after talking through it with someone else? Did you learn anything interesting through this process?

Exercise 1.16: storyboard (again!)

For this exercise, we’ll critique and revise a storyboard using the university elections example from Exercise 1.13. As a reminder, the background is as follows:

Imagine you’re a rising university senior serving on the student government council. One of the council’s goals is to create a positive campus experience by representing the student body to faculty and administrators and electing representatives from each undergraduate class. You’ve served on the council for the past three years and are involved in the planning for this year’s upcoming elections. Last year, student voter turnout for the elections was 30% lower than previous years, indicating lower engagement between the student body and the council. You and a fellow council member completed benchmarking research at other universities and found that universities with the highest voter turnout had the most effective student government council at effecting change. You think there’s opportunity to increase voter turnout at this year’s election by building awareness of the student government council’s mission by launching an advertising campaign to the student body. You have an upcoming meeting with the student body president and finance committee where you will be presenting your recommendation.

Your ultimate goal is a budget of $1,000 for the advertising campaign to increase awareness of why the student body should vote in these elections.

QUESTION 1: Your fellow council member created the following storyboard (Figure 1.16) for the communication to the student body president and has asked for your feedback. Critique the storyboard with these questions in mind:

- How is it currently ordered (chronological, leading with Big Idea, something else)?

- What points would you combine? What would you add? What would you remove?

- How would you suggest revising the storyboard based on your critique?

Figure 1.16 University elections colleague’s storyboard

QUESTION 2: You’ve now learned that the vice-president will be presiding over the meeting and will be deciding whether to approve your $1,000 advertising campaign. She is a busy woman and you know from others who have presented to her before that she will be hyper-focused when you are presenting but frequently has an overbooked schedule, often causing her to cut meetings short. In light of this primary audience change, reexamine your revised storyboard from Question 1C. What factors would cause you to make changes to the flow? Would you add or remove components?

QUESTION 3: Revisit the revised storyboard you created in 1C and answer the following questions:

- Why did you decide to put the call to action in its current location?

- In creating this storyboard, what were the advantages of using sticky notes over software?

- What benefits did you get from creating this storyboard?

You’ve practiced with me and on your own. Next, let’s talk through how you can apply the strategies we’ve covered in your work.

Exercise 1.17: get to know your audience

When communicating, it can be useful to start by identifying your primary audience and reflecting on what is important from their perspective. Even if you don’t know your audience, there are ways to get clarity on what drives them. Can you talk to them and ask questions to better understand their needs? Do you know people who are similar to your audience? Do you have colleagues who have successfully (or unsuccessfully) communicated to your audience and might have a perspective to offer? What assumptions can you make about what your audience cares about or motivates them, the biases they may have, whether they will find data important and if so, which, or how they may react to what you need to convey? As we’ve discussed, being clear on this can put you in a better position to successfully communicate.

If you have a mixed audience where different segments or people care about different things, it can be useful to create groups of similar audiences and work through this exercise for each of them. In cases where you identify overlap in their needs, this can be a useful place from which to communicate.

If you are making assumptions about your audience—and we nearly always are!—talk through these with a colleague or two. Do they agree with you? Have them help you identify and pressure-test your assumptions. Ask them to play devil’s advocate and take an opposing viewpoint, so you can practice responding to this. The more you can do to anticipate how things could go wrong and prepare for that, the better off you’ll be.

Pick a project where you need to communicate something to somebody. Identify specific actions you can take to better get to know your audience and understand what is important to them. What assumptions are you making about your audience when you do this? How big of a deal will it be if those assumptions are wrong? How else can you prepare for the audience to whom you’ll be communicating? List specific actions, then undertake them!

Exercise 1.18: narrow your audience

As we’ve discussed, it can be useful to have a specific audience in mind when we communicate. This allows us to really target our communication. The following exercise will help you think through how you can narrow your audience.

STEP 1: Consider a project where you need to communicate in a data-driven way. What is the project?

STEP 2: Start by casting a wide net: list all of the potential audiences who may care about what you will be sharing. Write them down! How many can you come up with?

STEP 3: Do you have them all? I bet there are more. See if you can add to the list you just made.

STEP 4: Next, let’s narrow. Read through the following questions and list the audience(s) that will care most in light of each of these things.

- What did you learn through the data? Which audience(s) will care about this?

- What is the action you are recommending? Who needs to take this action?

- What point are we at in time—what needs to happen now?

- Who is the ultimate decision maker or group of decision makers?

- In light of all of the above, who is the primary audience(s) to whom you need to communicate?

Exercise 1.19: identify the action

When we communicate for explanatory purposes, we should always want our audience to do something—take an action. Rarely is it as simple as, “We found x; therefore you should do y.” Rather, there are often nuances that come into play in determining how explicit we should be with the next step we want our audience to take. In some situations, we may need input from them to help determine an appropriate course of action. In other cases, we want them to come up with the next step on their own. In any event, we—as the communicators—should be very clear on what we think that action should be.

Consider a current project where you need to communicate something to an audience. List out the potential actions they could take based on the data you share. What is the primary action you want them to take? Be specific—suppose you will say the following sentence to your audience:

“After reading my deck or listening to my presentation, you should

_____________________________.”

If you’re having trouble, scan the following list and contemplate whether any of these might apply or spark ideas:

accept | agree | approve | begin | believe | budget | buy | champion | change collaborate | commence | consider | continue | contribute | create | debate decide | defend | desire | determine | devote | differentiate | discuss | distribute divest | do | empathize | empower | encourage | engage | establish | examine facilitate | familiarize | form | free | implement | include | increase | influence | invest invigorate | keep | know | learn | like | maintain | mobilize | move | partner | pay for persuade | plan | procure | promote | pursue | reallocate | receive | recommend reconsider | reduce | reflect | remember | report | respond | reuse | reverse | review secure | share | shift | support | simplify | start | try | understand | validate | verify

Exercise 1.20: complete the Big Idea worksheet

Identify a project you are working on where you need to communicate in a data-driven way. Reflect upon and fill out the following. A fresh copy of the Big Idea worksheet can be downloaded at storytellingwithdata.com/letspractice/bigidea.

Exercise 1.21: solicit feedback on your Big Idea

After you’ve crafted your Big Idea, the next critical step is to talk through it with someone else.

Grab a partner, your completed Big Idea worksheet, and 10 minutes. If they aren’t familiar with the Big Idea concept, have them read through the relevant section of SWD ahead of time, or simply tell them the three components (it should articulate your point of view, convey what’s at stake, and be a complete and single sentence). Prep your partner that you want candid feedback that will help you improve the overarching message you want to get across to your audience. Have them ask you a ton of questions so they can understand what you want to communicate and help you achieve clarity through the words that you use.

Read your Big Idea to your partner. From there, you can let the conversation take its natural course. If you’re feeling stuck, refer to the following questions.

- What is your overarching goal? What would success look like in this situation?

- Who is your intended audience?

- Is there any specialized language (words, terms, phrases, acronyms) that are unfamiliar or should be defined?

- Is the action clear?

- Have you framed what you want to happen from your perspective or from your audience’s point of view? If the former, how could you reframe for the latter?

- What is at stake? Will this be compelling for your audience? If not, how can you change it? “So what?” is always a good question to ask related to this—why should your audience care? What matters to them?

- Are there other words or phrases that may enable you to more easily get your point across?

- Can your partner repeat your main message back to you in their own words?

- “Why?” is probably the best question your partner can ask—and continue to ask to get you to articulate your logic in a way that will help you refine your Big Idea.

Revise your Big Idea during or following the conversation with your partner. If anything still feels rough or unclear, or if you’d simply like an additional perspective, repeat this exercise with someone new.

See Exercise 9.7 in Chapter 9 for a facilitator’s guide on how to run a formal Big Idea group session. Next, let’s talk about how you can use the Big Idea on team projects.

Exercise 1.22: create the Big Idea as a team

Are you working on a project as part of a team? Here’s a great exercise to undertake to make sure everyone is aligned and working towards the same overarching goal.

- Give each person a copy of the Big Idea worksheet (download from storytellingwithdata.com/letspractice/bigidea) and have them individually work their way through it and craft their Big Idea with the given project in mind.

- Book a room with a whiteboard or start a shared document and write out each of the Big Ideas. Ask each person to read theirs aloud.

- Discuss. Where are there commonalities across the various statements? Is there anyone who seems out of alignment? What words or phrases best capture the essence of what you want to communicate?

- Create a master Big Idea, pulling pieces from the individual ones and further augmenting and refining as needed.

This exercise helps ensure that everyone is on the same page and creates buy-in as people see components of their Big Idea flowing into the master Big Idea. It can also spark some awesome conversations that help everyone become clear on and confident about what needs to happen.

Exercise 1.23: get the ideas out of your head!

Let’s put into practice a good first step in the storyboarding process: brainstorming. Consider a project where you need to create an explanatory communication like a slide deck. Get a stack of sticky notes and a pen. Find a quiet workspace with a large empty table or whiteboard. Set a timer for 10 minutes. Start the timer and see how many ideas you can get out of your head and onto stickies. You can imagine that each small square reflects a piece of potential content in your eventual deck. That said, don’t filter your thoughts—rather, let it be a cathartic process (there are no bad ideas during this step). Don’t worry about order or how the ideas fit together at this point in the process. Simply see how many sticky notes you can fill up in a set amount of time.

Tip: do this low-tech exercise after you’ve spent enough time with the data to know what you want to communicate with it, but before you start creating content with your computer. This exercise is best done after you’ve created, solicited feedback on, and refined the Big Idea for the given project (see Exercises 1.20 and 1.21).

If you find you’re still on a roll writing down ideas when your timer goes off, feel free to add more time. After you’ve completed this exercise, move on to Exercise 1.24.

Exercise 1.24: organize your ideas in a storyboard

You’ve completed Exercise 1.23—the ideas are out of your head in writing on sticky notes—now it’s time to organize them. Step back and think about what overarching structure can help you tie everything together in a way that will make sense to someone else. It may be helpful to make additional stickies for meta topics or themes as you organize your ideas. Where can you group things together? What might you eliminate?

Speaking of eliminating, start a discard pile. For each sticky note you consider, ask yourself: does this help me get my Big Idea across? If you can’t come up with a good reason to include it, move it to the discard pile.

Here are some specific questions to contemplate as you’re determining what order could work best for your situation:

- How will you present to your audience: are you there live, over the phone or through a webinar, or sending something out that will be consumed on its own?

- What order will work well for getting your content across to your audience? Does it make sense to start with the action you want from them, build up to it, or something in between?

- What context is essential? Does your audience need to know it up front, or does it better fit later? How quickly should you answer “So what?”

- Do you already have established credibility with your audience, or do you need to build it? If so, how will you do that?

- Were there assumptions made in your work? When and how should you introduce those? What if your assumptions are wrong? Does that materially change the message?

- Do you need input from your audience? How and where can you best get that?

- At what point does data fit in? Does the data confirm expectations or run counter to them? What data or examples will you integrate and where?

- How can you best create common ground, get buy-in, and prompt action?

There is no single right path, but the answers to the preceding questions will help you think through different options that could work well for your given circumstance. If there is a non-message impacting data or other content that you can’t bear to get rid of, push it to the background—either physically by putting it later in the document (perhaps in the appendix) or visually by de-emphasizing it and putting emphasis on the most important components of what you need to communicate.

We’ll look at additional strategies for ordering content when we discuss Story in Chapter 6. In the meantime, move on to Exercise 1.25 and get feedback on your storyboard.

Exercise 1.25: solicit feedback on your storyboard

After creating your storyboard, talk through it with someone else. There are a couple of benefits to this. First, simply talking through it can be helpful. Doing so forces you to articulate your thought process, which can help illuminate alternate approaches. Second, sharing with someone else may introduce new perspectives or ideas that help you improve your storyboard.

This can be free-form: create your storyboard and then simply talk through it with a partner. Let the questions and conversation take their natural course. If you’re feeling stuck, or don’t have a partner handy and want to simulate this exercise, ask yourself the following questions:

- How are you presenting to your audience? Are you creating something they will consume on their own, or will you (or someone else) be presenting the material?

- Do the overall order and flow make sense?

- What is your Big Idea? Where will you introduce it?

- Does your audience care about all of these pieces?

- If there are pieces your audience cares less about but you still need to include, how can you keep their attention during this part?

- Where could things go wrong? How can you prepare for that?

- How will you transition from one topic or idea to the next?

- Is there anything that could be cut? Added? Rearranged?

If it makes sense to get stakeholder or manager feedback at this point, do it! This can be a great early check-in point to get confirmation that you’re on the right track or redirect your efforts—before you’ve invested a ton of time.

When you spend time up front identifying and getting to know your audience, crafting the main message, and storyboarding content, you emerge with a plan of attack. This both reduces iterations and helps you be more targeted with your communications. The resulting materials are typically shorter than they otherwise would have been. This leaves you more time to create quality content: slides and graphs. We’ll turn our attention there in the next chapter.

Exercise 1.26: let’s discuss

Consider the following questions related to Chapter 1 lessons and exercises. Discuss with a partner or group.

- What audiences do you communicate to regularly? What do the various audiences have in common? How are they different? How can you take the needs of your audience into account when communicating with data?

- Do you face a mixed audience when communicating with data? What are the main groups that make up this audience? Do you have to communicate to all of them at once? Are there any ways to narrow for purposes of communication? How can you set yourself up for success? Do others have related experience or learnings to share?

- Reflect on the Big Idea and the practice of distilling your message down to a single sentence. How did you find the related exercises in this chapter? In what situations does it make sense to take the time to craft the Big Idea in your work? Have you tried this on the job? Was it helpful? Did you encounter any challenges?

- Why are sticky notes good tools for storyboarding? Do you have other useful or recommended methods for planning content for your communications?

- What tip or exercise did you find most useful in SWD or this book on the planning process for communicating effectively? Which strategies have you employed? Were you successful? What learnings will you put into practice going forward?

- Was there anything covered in this section that didn’t resonate or that you don’t think will work in your team or organization? Why is that? Do others agree or disagree?

- Are there things you believe your work group or team should do differently related to the planning process for communicating? How can you make that happen? What challenges do you anticipate related to this and how can you overcome them?

- What is one specific goal you will set for yourself or your team related to the strategies outlined in this chapter? How can you hold yourself (or your team) accountable to this? Who will you turn to for feedback?