CHAPTER 9

Customer and Distribution Channel Profitability Analysis

THE ONLY VALUE A company will ever create for its shareholders and owners is the value that comes from its customers—current ones and the new ones the company acquires in the future. To remain competitive, companies must determine how to keep customers longer, grow them into bigger customers, make them more profitable, serve them more efficiently, and acquire more profitable customers.

But there is a problem with pursuing these ideals. Customers increasingly view suppliers' products and standard service lines as commodities. This means that suppliers must shift their actions toward differentiating their services, offers, discounts, and deals to different types of existing customers to retain and grow them. Further, they should concentrate their marketing and sales efforts on acquiring new customers who have traits comparable to those of their relatively more profitable customers.

As companies shift from a product‐centric and service line–centric focus to a customer‐centric focus, the myth that almost all current customers are profitable needs to be replaced with the truth. Some highly demanding customers may indeed be unprofitable! Unfortunately, many companies' management accounting systems aren't able to report the customer profitability information needed to support analysis for how to rationalize which types of customers are more attractive to retain, grow, or win back, as well as which types of new customers to acquire—and which types of customers are not attractive.

This shift in attention from products to customers means managers are increasingly seeking granular non‐product‐associated costs to serve customer‐related information as well as information about intangibles, such as customer loyalty and social media messaging about their company and its competitors. Today in many companies there is a wide gap between the CFO's function and the supply chain management, marketing, and sales functions. That gap needs to be closed.

THE PROBLEM WITH TRADITIONAL ACCOUNTING

Here is the basic problem. With accounting's traditional product gross profit margin reporting, managers can't see the more important and relevant “bottom half” of the total income statement picture—all the profit margin layers that exist and should be reported from customer‐related expenses such as distribution channel, selling, customer service, credit, and marketing expenses.

The supply chain, marketing, and sales functions already intuitively suspect that there are highly profitable and highly unprofitable customers, but management accountants have been slow to reform their measurement practices and systems to support the supply chain, marketing, and sales functions by providing the evidence. To complicate matters, the compensation incentives for a sales force (e.g., commissions) typically are based exclusively on revenues. Companies need to focus on growing profitable sales, not just increasing market share and growing sales. Compensation incentives for the sales force should be a blend of both customer sales volume and profits.

Who are the troublesome customers, and how much do they drag down profit margins? More important, once this question is answered, what corrective actions should managers and employees take to increase the profit from a customer? Measurements and a progressive management accounting system are the key.

Modern supply chain costing requires cost systems that have been restructured to provide a broader scope of actual and projected cost data so that managers can analyze the profitability of a variety of cost objects, such as products, service lines, projects, distribution channels, and customers. Customer profitability analysis is an obviously important tool within the umbrella of supply chain costing. This chapter describes this tool in more detail.

GOOD (LOW MAINTENANCE) VERSUS BAD (HIGH MAINTENANCE) CUSTOMERS

Every supplier has good and bad customers. Low‐maintenance “good” customers place standard orders with no fuss, whereas high‐maintenance “bad” customers demand nonstandard offers and services, such as special delivery requirements. For example, the latter constantly changes delivery schedules, returns goods, demands special rather than standard services, or frequently contacts the supplier's help desk. In contrast, the former just purchases a company's products or service lines and is rarely bothersome to the supplier. The extra expenses for high‐maintenance customers add up. What can be done? After the level of profitability for all customers is measured, they all can be migrated toward higher profits using “profit margin management” techniques.

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT'S NEED FOR CUSTOMER PROFITABILITY INFORMATION

In customer profitability analysis, the cost and revenue object of interest becomes the customer or the distribution channels to customers. More precisely, customer profitability analysis involves the process of tracing and assigning revenues and costs to customers or market segments based on costing's causality principle to determine their profitability.

Customer profitability analysis, including cost‐to‐serve expenses, represents a major step toward implementing supply chain costing. In many firms, analyzing how external customers drive costs represents their first initiative to capture costs and activities across multiple trading partners. Activity‐based costing (ABC) principles and a system to support ABC are essential for assigning costs to customers. ABC is described in detail in Chapter 10.

Customer profitability analysis is a tool that helps measure both the revenues generated and the resources used to serve specific customers, groups of customers, or distribution channels. This analysis helps managers identify and focus on the relatively more profitable customers and place less effort on the less profitable or unprofitable customers. Because of the product and service variety that permeates today's business environment, not all customers are equally profitable. A customer profitability analysis often shows that a small percentage of customers generate a large proportion of a firm's profits, and that many customers are actually unprofitable. Cost‐to‐serve focuses on the assignment of costs by customer to determine the total cost to service a customer or market segment. Customer profitability analysis—the technique more widely emphasized in management accounting—is the focus of the discussion throughout the remainder of this chapter.

Like value chain analysis, customer profitability analysis requires a modification in the way costs are viewed and managed. Supply chain costing is complicated by the variety of choices made available by the advent of lean processes. For example, what does it cost to sell identical products under different names or brand numbers in big‐box stores, in mom‐and‐pop outlets, and over the internet? How are choices to deliver products directly to retail stores, to distribution facilities, by mail or UPS to individual customers, and by other means justified? Which customers or distribution channels are relatively more or less profitable? These are increasingly important questions in a world where a firm must compete with many other suppliers for customers with new and complex expectations.

Understanding customer profitability is critical to making decisions about what and how to sell and deliver different products and services. Management must determine which of the many market niches and different types of customers they wish to serve. Considerable management interest exists in determining which customer groups are most loyal, which require extra levels of support or service, how customer actions affect costs, and whether there are customers the firm needs to let go—to terminate the relationship and let competitors take on those customers and lose profits from them.

EXHIBIT 9.1 Information Managers Need in Today's Environment

Source: Adapted from Shahid Ansari, Jan Bell, and Thomas Klammer, “Customer Profitability Analysis,” in the modular series Management Accounting: A Strategic Focus (Ansari, Bell, Klammer: Lulu.com).

| Who are the firm’s “best” (most profitable) customers? |

| Who are the “problem” customers? How can they be made more profitable? |

| What is the value of keeping or increasing customer loyalty? |

| What customer actions result in increasing selling, service, or support costs? How can the firm work with these customers to avoid such cost increases? |

| Which customers should get price discounts and receive special promotions? |

| What customer support activities are costly and how can these activities be done at less cost? |

| Are there more profitable means of distributing products or service, such as over the internet? |

Exhibit 9.1 lists some of the customer information supply chain managers need in today's environment. The information systems that managers need to answer these and similar questions are significantly more complex than the traditional systems many firms continue to use.

AN APPROACH TO CUSTOMER PROFITABILITY ANALYSIS

When performing customer profitability analysis, information about the revenue generated by a customer and the direct costs of the product or service the customer buys is usually readily available. However, the gross margin information that typically results is not a good estimate of customer profitability in a world where customer demands on support services vary widely.

Completing a customer profitability analysis requires an understanding of how and why there are differences in the support costs associated with serving a customer, group of customers, or a particular distribution channel. Information on who the customers are as well as what, when, how, how often, and even why they buy is essential. There is a need to accumulate data on what it costs to sell, deliver, provide customer support, and meet other customer‐generated costs. This type of data often resides in different functional systems such as logistics, sales, marketing, and finance. The data usually needs to be reclassified by type or activity to be useful. The importance of cross‐functional information sharing is critical. Exhibit 9.2 shows customer support activities classified into four major types of subprocesses and lists several examples of the types of activities that support each process.

Some of these activity costs may be readily traceable to individual customers or channels if the firm has properly structured information. The salary of a salesperson dedicated to a single customer is easily traced to that customer. Other costs may be shared among several customers or market segments and will require significant additional analysis and the use of reasonable cost allocations. The cost of the customer support personnel who respond to inquiries from a group of 10 large customers might be allocated based on the percentage of time spent with each customer. Still other costs, such as designing and maintaining a website, may be general to all customers and it may be inappropriate to allocate this type of costs to customers when doing a customer profitability analysis.

EXHIBIT 9.2 Customer‐Related Subprocesses and Activities

Source: Adapted from Shahid Ansari, Jan Bell, and Thomas Klammer, “Customer Profitability Analysis,” in the modular series Management Accounting: A Strategic Focus (Ansari, Bell, Klammer: Lulu.com).

Several basic steps are part of customer profitability analysis:1 create customer profiles, compute the revenue generated from each customer, compute the cost of activities consumed in servicing customers, compute customer profitability by combining the revenue and cost data, and use the analysis to design the right customer mix and strategy.

Much of the Data Already Exists

This information often resides in marketing, since most organizations already have a fairly detailed profile of their customers. Information on what goods and services customers purchase and how often they purchase them (such as preferring morning deliveries) is readily available. Firms use this information to make special offers or to inform customers of new products or services.

Computing the revenue generated by a customer from all sources is relatively straightforward. Payment records are an obvious source of this information. Part of the analysis may become a bit less certain where there are indirect revenues, such as what a bank can earn from cash kept in a customer checking account. When a supply chain process, such as manufacturing flow or order fulfillment, is part of the product cost, estimating how much of the revenue to assign to the process requires informed judgment.

Revenue generation costs money. A transportation company must buy fuel, pay drivers, buy insurance, rent or buy facilities, repair equipment, and so forth to generate a stream of delivery revenue. Determining how much cost to assign to an individual customer or class of customer requires a careful analysis of what drives the costs so a reasonable allocation of these costs to the customer can be made. There are also significant other costs that need to be considered to estimate customer profitability. For example, what does it cost to acquire and keep a customer? How often does a customer return goods, require special deliveries, make service inquiries, or demand unique services? What is the cost of each of these extra activities? The analysis must attempt to consider all the costs associated with a customer or class of customer.

Customer profitability analysis is often done for several timeframes, ranging from a year to a lifetime. Managers can use this profitability information to structure or restructure the customer mix or to modify customer strategy. Assume the delivery costs for a customer or a group of similar customers are too high. The shipping firm may work with customers to restructure how it makes deliveries and thus convert unprofitable customers into profitable customers.

When the analysis is complete, it is common to classify customers into groups based on their relative profitability. A high‐revenue, low‐cost customer is more valuable than one that generates high revenues but also has high costs. The least desirable customer is one that generates low revenues and high costs. It would make sense to eliminate this customer from the mix unless it can be made more profitable.

Reasons to Rationalize Which Customers to Focus On

Recall from Exhibit 9.2 that managers want to know the value of maintaining customer loyalty. Typically, loyal customers buy more and may be somewhat less price‐sensitive. This customer provides an ongoing stream of profits without the firm's having to incur the costs of acquiring a new customer. In fact, the loyal customer may even help the firm generate new customers. Actions taken to encourage customer loyalty may also help move other customers into a higher level of customer profitability.

A firm may choose to keep a low‐profit customer. Demographics might suggest that this customer will become more profitable over time, perhaps because of anticipated growth or higher income levels. Cultivation of this customer for the generation of higher lifetime profits is more important than avoiding short‐term losses or low profitability. A firm may also choose to keep low‐profit customers in the short term because a significant percentage of costs are committed in the near term, and there are not opportunities to acquire higher‐profit customers immediately. It is essential to find ways to lower costs or modify unprofitable customers' behavior so it makes sense to retain them.

VALUE OF CUSTOMER PROFITABILITY ANALYSIS

Customer profitability analysis forces decision makers to identify and understand the activities required to serve customers, evaluate how customers behave, and associate costs with these activities and behaviors. Customer relationships are understood and valued, as there is a focus on ensuring customer satisfaction rather than just minimizing costs. However, customer profitability analysis also shows why it is unwise to simply provide whatever the customer wants. It imposes discipline on management decisions by making the cost to serve visible throughout the firm. More focus is put on what is best for the organization than on what is best for a functional area such as marketing or production.

There is an increasing emphasis on developing customer costing techniques. This emphasis stems from the tremendous diversity in the services being performed for downstream trading partners and the recognition that this diversity results in major differences in workload, resources, and costs to the firm. Managers believe that in some instances these differences make customers unprofitable to the firm, but their existing costing systems do not possess the capability to isolate costs by customer.

The traditional general ledger cost systems employed by most firms focus on product costing and do not have the capability to accurately determine the costs of serving different customers. A product costing approach relies on a limited number of cost drivers such as labor or materials to assign costs. Traditional information systems typically do not give much attention to customer‐related costs, such as order filling, sales support, billing and collection, credit checking, or warehousing. Customer‐related costs are aggregated under sales, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses and, as an indirect cost, are arbitrarily allocated to products based on a proportion of direct labor, sales volume, number of units produced, square feet/meters, or some other basis. Such measures do not represent good measures of what it costs to serve customers who make diverse demands on supply chain activities. To be more specific, they violate costing's causality principle.

Activity‐Based Costing (ABC) Resolves Deficiencies with Traditional Costing

Customer‐driven costs, while often large, are often invisible to decision makers and thus do not receive sufficient management attention. The use of arbitrary cost allocation methods provides managers with little visibility and insight into what drives these costs or how diversity in customer requirements or behavior drives differences in customer costs and profitability. Customers often have a greater effect than products on how many costs are incurred. This situation is especially true in customer‐facing processes or functions such as sales, marketing, logistics, and customer service. Most managers do not have accurate information regarding customer profitability because of the problems associated with traditional costing.2

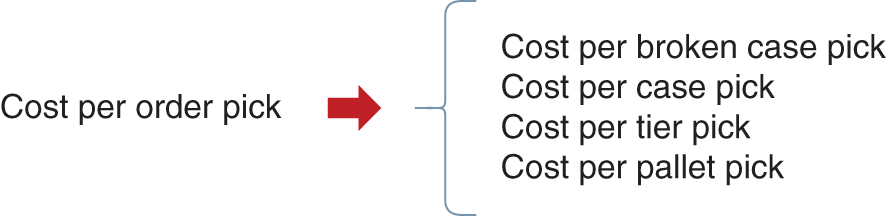

Customer profitability analysis overcomes the limitations of traditional costing through the use of activity‐based costing (ABC). Firms that employ or develop customer profitability analysis rely on an activity‐based approach for assigning costs to distribution channels and customers. ABC determines the cost of work activities performed to service customers and uses cost drivers to assign the cost of those resources consumed by these activities. An activity‐based approach permits the assignment of indirect costs (e.g., SG&A), commonly referred to as “overhead,” to customers through the use of activity drivers to calculate unit‐level cost consumption rates such as cost per customer order, cost per delivery, cost per sales call, and cost per customer return. These activities can be expanded to reflect the diversity of customer requirements. Exhibit 9.3 shows how the order‐picking activity could be further disaggregated to reflect differences by customer orders.

EXHIBIT 9.3 Developing Activities to Capture Differences in Customer Requirements or Behavior

Activity‐based costing (ABC) is a management accounting method that reasonably accurately traces the consumption of an organization's resource expenses (e.g., salaries, supplies) into its products, SKUs, service lines, and to the types and kinds of distribution channels and customer segments that place varying degrees of workload demand on the company. It should no longer be acceptable not to have a rational system of assigning so‐called nontraceable costs to their sources of origin—the resource expenses. ABC is that system. Yet, sadly, many companies still do not use ABC. The consequence is that managers are receiving flawed and misleading cost information, which means misleading profit margin information.

The use of an activity‐based costing (ABC) approach substantially increases the accuracy of cost and profitability information provided to management. It replaces the broadly averaged cost allocations by tracing and assigning how resource expenses are consumed by outputs using cause‐and‐effect relationships with cost drivers. Exhibit 9.4 compares the costs and profitability obtained from a traditional approach versus an activity‐based approach. The traditional approach assigns SG&A expenses to each customer based on their proportion of sales revenue. The ABC approach assigns the components within SG&A based on actual consumption. These results send very different signals to management. The traditional approach implies that indirect costs vary in direct proportion with sales. Consequently, any additional sales volume would appear to be equally effective in increasing the firm's profitability. However, not all customers are created the same, and their behavior will drive a different mix of activities being performed within the firm. The activity‐based analysis traces costs to customers based on how they consume these different activities. The results of an activity‐based analysis may produce dramatic shifts from the profitability reported by traditional cost systems. These differences are driven by the extent of the firm's indirect, customer service costs, and the service demands placed on the firm by its different customers.

Customer profitability analysis provides powerful information that supports management decision making. At the individual firm level, managers can manage costs and revenues to improve the profitability of individual firms. At the aggregate level, customer profitability can assist managers in two areas. Customer profitability analysis provides insights regarding the firm's risk and its dependence on specific customers or market segments. Management can use the analysis to develop market segments based on profitability and develop corresponding strategies.

Management can also use the results to determine how best to manage revenues and costs to improve overall profitability. Without a customer profitability analysis, managers do not have a true picture of how individual customers affect the firm's costs. As a result, the greatest benefit of the analysis is accurate information regarding which customers are profitable and which are not. Managers can use this information to adapt or develop strategies to make underperforming customers more profitable. Customer profitability analysis might reveal that many of a company's smaller customers are unprofitable. By “breaking even” on these customers, the firm could substantially improve overall profitability. Managers could then respond by using a lower‐cost delivery process and by offering customers incentives to use a less expensive order placement process. These changes would enable the firm to improve the profitability of these customers without degrading customer service or losing sales.

EXHIBIT 9.4 Comparison of Customer Profitability Computed Using Traditional versus Activity‐Based Approaches

| Customer Profitability (Traditional Costing) | Company | Cust A | Cust B | Cust C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales ($M) | 20,000 | 4,500 | 5,500 | 10,000 |

| Less returns & allowances | 2,000 | 0,250 | 0,500 | 1,250 |

| Net Sales | 8,000 | 4,250 | 5,000 | 8,750 |

| Cost of Goods Sold | 9,500 | 2,200 | 2,600 | 4,700 |

| Manufacturing Contribution | 8,500 | 2,050 | 2,400 | 4,050 |

| Sales, General & Administrative | 5,700 | 1,283 | 1,568 | 2,850 |

| Controllable Margin | 2,800 | 0,768 | 0,833 | 1,200 |

| Customer Profitability (Activity Based) | Company | Cust A | Cust B | Cust C |

| Sales ($M) | 20,000 | 5,000 | 6,000 | 9,000 |

| Less returns & allowances | 2,000 | 250 | 500 | 1,250 |

| Net Sales | 18,000 | 4,250 | 5,500 | 8,750 |

| Cost of Goods Sold | 9,500 | 2,200 | 2,600 | 4,700 |

| Manufacturing Contribution | 8,500 | 2,050 | 2,900 | 4,050 |

| Variable selling and logistics costs: | ||||

| Sales & advertising | 1,200 | 0,310 | 0,290 | 0,600 |

| Transportation | 2,000 | 0,200 | 0,250 | 1,550 |

| Warehousing | 0,500 | 0,050 | 0,075 | 0,375 |

| Order processing | 0,300 | 0,020 | 0,060 | 0,220 |

| Customer relationship | 0,700 | 0,100 | 0,200 | 0,400 |

| Inventory carrying costs | 1,000 | 0,100 | 0,200 | 0,700 |

| Segment contribution margin: | 2,800 | 1,270 | 1,825 | 0,205 |

EXHIBIT 9.5 Cumulative Plot of Customer Profitability

Source: Adapted from Gary Cokins, Activity‐Based Cost Management: An Executive's Guide (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), p. 103. Used with permission of the author.

Cumulative Profit Graphs: The “Whale Curve”

Customer profitability analyses can be used to determine the risks and dependence existing in a firm's customer base. A cumulative plot of customer profitability from most profitable to least profitable is used to demonstrate the level of risk and dependence (Exhibit 9.5). These graphs are often referred to as “whale curves” because they have the shape of a whale.

For example, a review may show that a relatively small proportion of customers accounts for all the firm's profits. These firms subsidize the costs incurred in supporting the remaining firms. In this situation, the firm is highly dependent on a small number of firms for its profitability. Managers need to mitigate their risk by focusing on these customers. These firms will be targeted for higher service levels and sales and marketing retention efforts. In addition, managers should attempt to reduce their dependence on these firms by increasing the profitability of the remaining customers. They can do this by increasing the revenues from these customers, changing their behavior to lower costs, or developing stronger customer relationships. A different plot of customer profitability may reveal an opportunity to improve profitability by focusing only on a small number of very unprofitable. By focusing on just these firms, managers can significantly improve profitability by determining what is causing the cost‐to‐serve to exceed revenues and then taking appropriate action.

Customer profitability analysis can be used to segment the firm's market based on profitability. Managers can review customers in different categories to determine whether the customers with similar profitability share a set of attributes. Based on this analysis, managers can use the profile to target customers with similar attributes. They understand what makes these customers profitable and the requirements to serve them. In addition, managers can recognize which customers to avoid if they match the profile of unprofitable customers. This recognition gives managers an edge in targeting potential customers—an edge that their competitors are unlikely to replicate, given the extent of customer profitability analysis used in most supply chains.

Expanding the CFO's Service to Managers

Much has been written about the increasing role of CFOs as strategic advisors and their shift from bean counter to bean grower. Now is the time for the CFO's accounting and finance function to expand beyond financial accounting, reporting, governance responsibilities, and cost control. They can support the supply chain management, sales, and marketing functions by helping them target the more attractive customers to retain, grow, and win back and to acquire the relatively more profitable ones.

NOTES

- 1. The steps listed are taken from Shahid Ansari, Jan Bell, and Thomas Klammer, “Customer Profitability Analysis,” in the modular series Management Accounting: A Strategic Focus (Ansari, Bell, Klammer: Lulu.com). This module includes a detailed number example of the customer profitability analysis process.

- 2. Douglas M. Lambert, “Which Customers Are the Most Profitable?” CSCMP's Supply Chain Quarterly 2, no. 4 (2008); Reinaldo Guerreiro, Sérgio Rodriqus Bio, and Elvira Vazquez Villamor Merschman, “Cost‐to‐Serve Measurement and Customer Profitability Analysis,” The International Journal of Logistics Management 19, no. 2 (2008): 389.