CHAPTER 5

Why Supply Chain Cost Systems Differ from Traditional Cost Systems

SUPPLY CHAIN COST SYSTEMS should support a firm's strategic and production choices as well as the broad variety of decisions related to supply chain processes that executives and managers need to make. The importance of restructuring cost systems so the information they provide more effectively supports supply chain management is made repeatedly by supply chain executives. Information needs should drive the design of supply chain cost systems, and the information should provide insights and support the decisions managers make at the strategic, tactical, and operational levels.

Supply chain costing is complex and many choices exist to assist firms in better managing supply chain processes. The identification of what cost information is needed and the selection of the appropriate tools for measuring, reporting, and analyzing supply chain costs are key challenges. The next several chapters can assist executives in making these choices. This chapter provides a structural foundation for the more explicit discussion of the costing tools. Modern supply chain cost information must match costing methods and tools with the time frame and nature of the decision, while thinking outside the box of functional and internal costs to include costs across trading partners in the supply chain. Firms must adopt a strategic perspective for managing supply chain costs and managers must understand how modern supply chain costing differs from traditional costing.

COST DATA NEEDS

Responsibility cost center–based cost systems are in place in almost every organization. They are reported in the general ledger accounting system. These systems collect data by the department, division, or functional area where a manager has spending responsibility. While useful for safeguarding assets, responsibility cost center expense data is of limited value for strategic analysis or decision making because the focus is on who incurred a cost rather than on whether the right activities are being supported. Responsibility cost center–based systems lack the characteristics needed to properly support the variety of activities that are inherent in increasingly lean supply chain processes. However, they can, in some situations, be adapted to capture cost data that is useful in this changing environment.

Consider standard costing, a tool that is widely used. When a firm routinely fills the same types of orders for the same customers, the cost factors involved in providing this service are easy to identify. Standards for each cost factor are developed and cost systems routinely collect information on the small number of cost factors that drive costs in this type of mass production process. Actual costs are compared with expected costs in each category and area. The reasons for cost deviations, commonly referred to as cost variances, are analyzed as part of an ongoing effort to maintain costs at a predetermined level and to evaluate manager performance.

Change to Reflect Modern Data Needs

When the order fulfillment activities in the firm vary widely, a more complex system is needed to accumulate the cost of these activities. The nature of costs incurred broadens, costs do not recur with as much frequency, and they are more difficult to predict. To attempt to develop standards for these changing activities, different or modified costing tools are required. Firms are adapting their standard costing systems to focus on activities that recur. There is analysis of differences in actual and standard costs of activities to find ways to improve processes such as order fulfillment or demand management.

The boundaries of the firm represent the limit for data collection when the focus is on financial reporting. Strategically, decisions must be made about which activities in a supply chain process the organization will conduct internally and which it will leave for other members of the supply chain. Consideration should be given to the costs and profits of other trading partners in the supply chain. Supply chain executives emphasize the importance of supply chain cost managers having this external focus. There are numerous examples of how and why their supply chain costing systems attempt to measure how much the decisions made by other members of the supply chain influence their firm's costs. Knowledge of these externally driven upstream and downstream costs help manage these costs more effectively.

Lean product or service providers typically need to use more sophisticated cost analysis tools to handle the increased level of costing complexity. When a firm produces or delivers a single product using mass production methods, cost (price) is the primary strategic emphasis. Understanding how changes in volume influence costs is essential. If a firm produces many specialized products or customizes delivery service to various customers, there is more complexity. Cost data is needed to analyze how costs change with a wider variety of cost drivers. Other factors, such as quality and time, also continue to increase in importance.

MANAGEMENT PERCEPTION OF COSTS

Managers frequently express frustration with a lack of confidence in the cost information used within their firms. They are typically looking for accurate and stable cost information to plan, budget, and evaluate the performance for their operations and the cost information provided to them appeared “soft,” imprecise, or, in some instances, unreliable. This situation appears to result from the ambiguous nature of cost and expectations that may be unrealistic in an increasingly lean environment where change rather than stability is the norm.

There are many ways to define cost, and the lack of clear and consistent understanding of the many ways cost can be defined and used will jeopardize actions to implement supply chain costing. Management accountants across a supply chain assign costs in different ways depending on the focus of their costing efforts. A product and service costing approach produces quite different results than those derived from a customer‐oriented costing approach. One firm's standard costing system may assign only direct costs and use an arbitrary scheme for assigning indirect costs (commonly referred to as overhead). Another firm in the supply chain may use an activity‐based costing (ABC) approach that attempts to trace and assign costs more accurately. ABC will be discussed in Chapter 10.

Why Allocation Matters

How a firm allocates indirect or overhead costs has a major influence on supply chain costs and thus on supply chain management. The majority of firms' overhead costs are still arbitrarily assigned to work centers or activities using single allocation bases such as unit volume, labor hours, headcount, or revenue. These do not have cause‐and‐effect relationships. Managers who have little to no control over the overhead costs allocated to their responsibility center are still expected to continually reduce costs by a fixed percentage or generate sufficient returns to recover these allocated costs. The allocation (assignment) techniques are an important influence of managers' behavior. Since performance is evaluated against these costs, they attempt to find means to avoid or minimize these allocations. The cost allocation process drives what they do. In some instances, it drives them in directions contrary to what is best for the firm or the customer. Effective cost allocations should align with the firm's objectives. Performance measures should support those objectives to ensure the desired outcome. Cost allocation is an area of such importance that it is addressed in Chapter 10.

Not having clear cost definitions makes communication and collaboration within the supply chain very challenging. Most firms use accounting systems that provide detailed information regarding labor, material, and other direct expenses. If asked about the influence of indirect costs, the costs of processes, or the cost to serve specific customers, managers generally indicate that their cost systems do not provide this information. However, they recognize that knowing these costs is needed to manage their supply chains. Even in firms with intricate standard cost systems, managers have difficulty determining what it costs to produce a custom product or service. This is primarily due to the cost averaging that occurs at some level. Measuring customer profitability is discussed in Chapter 9.

A lack of accurate and timely data is the “Achilles heel” of costing. Data issues and data structure can prevent effective and accurate cost allocation in some firms.

One firm cited the need to get their arms around the cost drivers for total load (TL) and less than total load (LTL) deliveries to control their transportation costs. The firm's prior cost system did not capture or break out the cost differences when deliveries were multistop and did not differentiate between brokered, commercial, or private deliveries. The firm developed an allocation system that provided cost information for the different types of deliveries and pallets delivered. When they were able to capture this information, accurately assign costs, and understand exactly what was driving their costs, the doors opened for them to really drive supply chain costs in the right direction. The senior executive responsible for this process stated that their firm was able to take millions of dollars out of their supply chain costs and that they have been able to keep transportation costs stable despite fluctuating fuel costs and other factors occurring in the economy.

Senior managers find their subordinate managers feel discomfort and frustration with the cost data. They frequently distrust the cost information in the accounting system. Many executives state that they routinely question the results of cost study teams due to the many assumptions made to derive costs and the inability to reconcile these special studies with the corporate cost management system. In some instances, they have mandated that all cost studies be coordinated with the CFO to ensure some degree of consistency. As a result, these managers consider it difficult to communicate internally in cost‐based terms and even more difficult to communicate externally with their trading partners.

An approach some firms use to overcome inconsistencies in costs is to assign a financial analyst, or sometimes a financial controller, to the supply chain function. The analyst typically fills a matrix position within supply chain management but continues to report to the CFO. The position has the responsibility of ensuring that the cost data, reports, and performance measures used in supply chain processes are consistent with the information in the financial management system. These individuals usually become the point of contact for costing information. The individuals serving in these positions report numerous challenges, including obtaining the nonfinancial data for developing effective cost drivers; the complexity associated with capturing and reporting cost information by product, division, supply chain, and customer; and developing effective approaches for assigning costs when a large portion of the costs are common to multiple products or customers. The analysts indicate that they experience little to no difficulty in working in a matrix assignment; however, they find the learning curve for understanding supply chain management and what it encompassed to be very daunting.

SUPPLY CHAIN COSTING INCREASES THE COMPLEXITY OF COST SYSTEMS

The pursuit of supply chain costing adds complexity to an organization's costing efforts. Internally, the firms find that they need to classify costs in multiple ways. Any exchange of cost information, to or from trading partners, increases complexity by adding more costs and drivers to the analysis.

Managers and those responsible for implementing supply chain costing need to recognize that cost information becomes progressively more complex as the firm moves through the supply chain costing steps described in this book. Some firms are still using only traditional cost systems and others, within the same supply chain, have detailed activity‐based costing (ABC) systems based on multiple cost classifications. Firms just beginning the supply chain cost journey typically rely on traditional cost systems with a limited number of identified cost drivers and costs classified by function or natural accounts in the general ledger accounting system. Costing complexity increases as firms attempt to understand key cost drivers, both internal and external to the firm. The use of multiple drivers enables these firms to conduct more detailed analysis of their internal value chains.

The firms furthest along in supply chain costing employ cost techniques such as target costing, kaizen costing, cost‐to‐serve, or other process‐based approaches to develop their costs. Many firms are making an effort to identify activities and trace costs. However, few firms have their supply chain employees assign their time (work) by activity. Instead they rely on industrial engineers and other process experts to determine the resources consumed by each activity and the resulting cost per activity and their activity cost drivers.

Understanding Supply Chain Costs

As firm management attempts to better understand supply chain costs, the need for multiple cost classifications increases. Costs may be classified by end‐to‐end processes (value streams) to better understand how different functions affect total process costs or the cost per output (outcome). The classification of costs by product or family group (product costing and profitability) provides greater insight regarding how product differences affect activity and process costs. Product classifications enable a firm to more accurately assign costs by strategic business unit (SBU) and better support each SBU.

Classification of costs by customer occurs where customer differences have a significant effect on cost. Those differences include product or packaging customization, order placement, cycle time, and delivery requirements. In some instances, firms extensively collaborate with selected customers to improve processes. In other cases, they identify how other process costs, such as research and development or manufacturing, are affected by customer demands. Depending on the size and uniqueness of the customer, the cost‐to‐serve (customer profitability) analysis sometimes breaks out costs separately for key or very large or key accounts and aggregates smaller, similar customers by class of trade. However, customer account profitability can be obtained even for very small accounts if warranted.

Cost classification by distribution channel, or supply chain, often is just beginning when firms commit to attempting to better understand how external drivers and business practices affect internal costs and the costs of other trading partners. Executives note that the most apparent need for this cost classification scheme occurs when the firm operates in distinct supply chains that use different business practices and thus generate large cost differences. If a manufacturer uses multiple channels and sells directly to the end user over the internet, through distributors, to large retailers through distribution centers, and does direct store delivery (DSD), the costs of each approach differ markedly. As an example, a supplier may want to recognize the need for capturing these cost differences to rationalize the use of multiple channels with the same retailer where the channel varied depending on the product, region, order size, retail store location, or end user.

Fluctuations in transportation and delivery costs has intensified interest in classifying costs by supply chain. Supply chain managers note that they sometimes acquire the same product from multiple suppliers or different locations. Rising transportation costs have caused these managers to more carefully consider and calculate the total landed cost (TLC) when sourcing, since higher transportation costs frequently surpass any savings obtained by always sourcing from the lowest‐price supplier. Managers have a greater interest in comparing the costs of different supply chain strategies such as offshoring versus near‐sourcing. Decisions in these areas commit the firm to future costs, and managers need to understand and explicitly evaluate the nature and size of this commitment.

REASONS SUPPLY CHAIN COSTING MUST DIFFER FROM TRADITIONAL COSTING

There are constant examples and reminders that traditional general ledger accounting systems are of limited value in providing the types of cost information needed for modern supply chain costing. The focus of traditional costing systems is functional, using department cost centers designed to support external financial reporting, and strongly emphasizes product costing. These systems are based on transactions with customers and suppliers as well as internal transactions between segments of the firm. Traditional systems are internally focused. They are also historically focused and do not measure or report future prospective costs. Despite these shortcomings, most companies in the United States and abroad continue to rely on traditional systems as the primary source of cost information. In contrast, supply chain cost systems need to help the decision maker estimate and manage prospective costs because these costs can still be changed.

Technological limitations historically meant that cost data structured to support external statutory financial reporting for government regulators was by default the primary basis of internal cost reports. Cost accounting systems were developed within the confines of the functional internal cost structure to support mass production manufacturing. Their primary focus was on managing and controlling direct materials, direct labor, and inventory. There was limited emphasis on managing marketing, selling, customer service, and administrative costs or, often, even manufacturing overhead costs. Tools such as budgeting, capital budgeting, and standard costing were developed to help plan for future costs. Only recently, as new strategic cost management tools emerged, have more detailed costing systems gained traction in many firms and for specialty areas such as supply chain costing.

Supply Chain Costing Needs

Supply chain costing requires a different focus and emphasis. Cost information that spans the supply chain from inception to disposal is needed to effectively manage and control supply chain performance. Supply chain processes cross multiple functional and responsibility center lines. The most progressive managers stress that one of the primary points their firm emphasizes is to develop appropriate cost information for the overall process. Supply chain cost systems need to incorporate many of the characteristics of lean production methods with there being a particular emphasis on communication between functional areas and trading partners. Different types of cost information are needed to support strategic and operational decisions. Both are essential, but a major focus of the supply chain costing effort should be on future prospective costs. Chapter 11 discusses projecting costs, including budgeting and rolling financial forecasts.

Supply chain processes add value when they satisfy customers and still improve organizational profits. Both costs and revenues need to be managed. Internal and external customer requirements within the supply chain determine the products or services they provide. If a customer seeks to increase delivery frequency or modify their right of return, supply chain costing tools should help decision makers analyze how these changes impact profitability. Decision makers need to focus on more than simply reducing cost.

Many costs within supply chain processes are traditionally classified as part of distribution, marketing, selling, customer service, and administrative costs. Supply chain managers have long been aware that careful attention must be paid to these costs as well as traditional product costs. Some managers are having success in getting support for cost system modifications that elevate the level of attention paid to these types of costs. Some firms now link expenditure decisions within a supply chain process to projected changes in revenue and then monitor the actual results of the decision.

Recall that supply chain processes span firm units and functions and extend to customers and suppliers throughout the value chain. By design, supply chain costing systems should help in the analysis of what each process costs and how effectively the process functions. Decision makers must understand what occurs and why these activities are necessary.

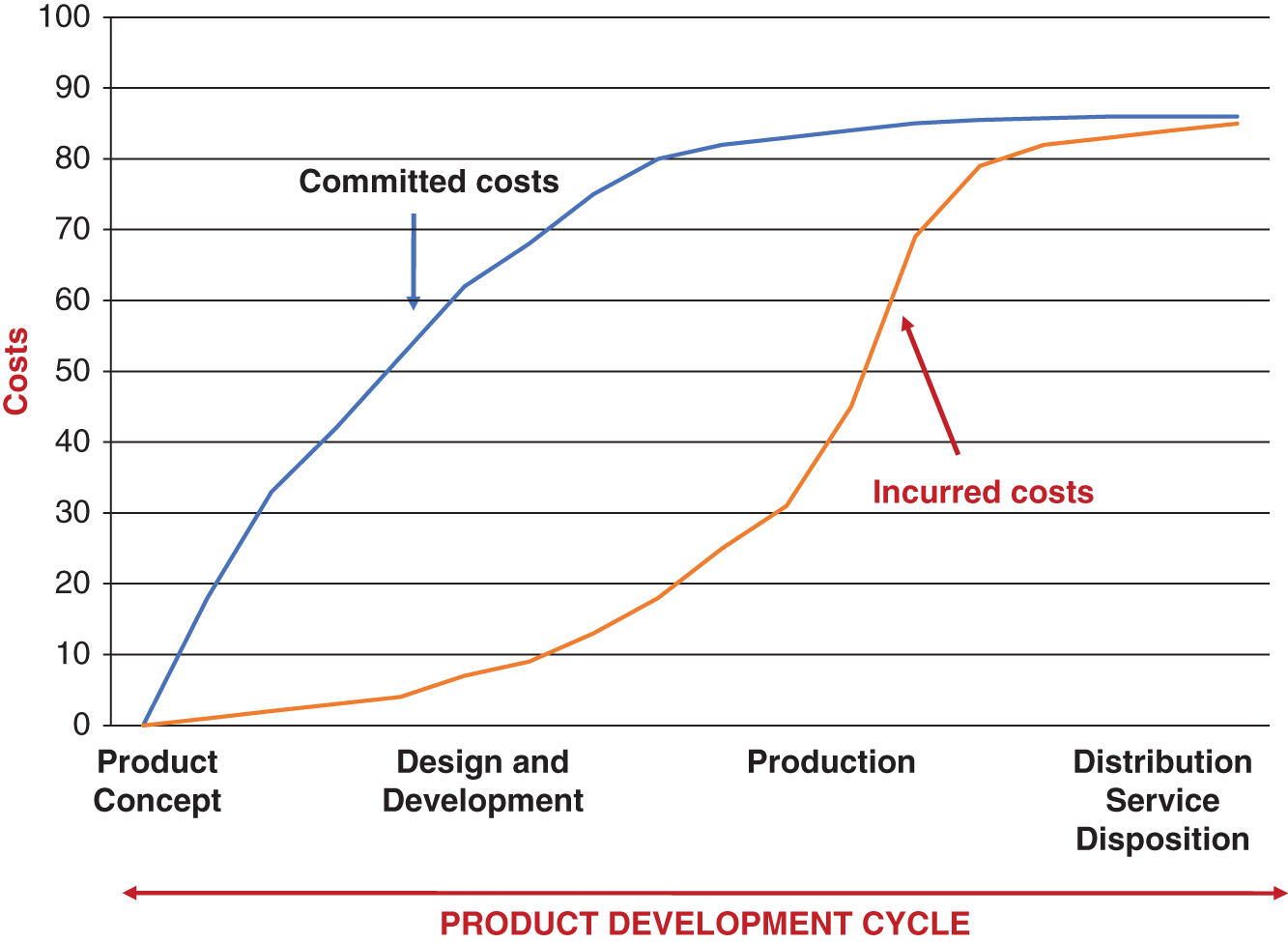

EXHIBIT 5.1 Committed Costs versus Actual Supply Chain Costs

Source: Shahid Ansari, Jan Bell, and Thomas Klammer, “Target Costing,” in the modular series Management Accounting: A Strategic Focus (Ansari, Bell, Klammer: Lulu.com).

Committed Costs

The majority of product or process costs become committed during conception and design. As shown in Exhibit 5.1, this commitment occurs much earlier than when the actual expenditures are made. Multiple studies demonstrate that 80% of total lifetime costs are committed before the first unit of a new product is produced. Even in the service areas, 60% or more of the lifetime costs are often committed prior to initial service delivery. The same is true for key supply chain decisions. A decision to use company‐owned vehicles to make deliveries to customers commits the firm to a large portion of the delivery costs. A decision to set up a call center to handle customer orders and informational requests commits the firm to a large portion of the call center costs. It is essential to manage supply chain costs early in the process, thus there is an extensive focus on prospective or future costs throughout this book.

Supply chain costing needs to focus on costs incurred throughout the supply chain in order to manage these costs. It is essential to select the most appropriate tools for measuring and managing these costs. There must be a focus on understanding and improving supplier costs while managing the profitability of customers.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TRADITIONAL AND SUPPLY CHAIN COSTING

Supply chain costing differs from traditional costing in several important aspects, summarized in Exhibit 5.2. These differences include objectives, focus, cost objectives, linkages, precision, scope, and visibility. The following discussion briefly compares and describes the differences and their importance.

Objective

Traditional costing focuses primarily on tracking expenses and supporting the development of financial reports. Although traditional costing provides important information, most of the reports generated offer little insight into how effectively the supply chain is operating or how managers' decisions are affecting value creation. Supply chain costing focuses on providing the information needed to support cost‐based decisions. Managers gain greater visibility into how activities within supply chain processes consume costs and how their decisions affect the performance of these activities and drive costs differently.

EXHIBIT 5.2 Comparison of Traditional and Supply Chain Costing

Source: Exhibit adapted to include research results and previous comparison from Mike J. Partridge and Lew Perren, “Cost Analysis of the Value Chain: Another Role for Strategic Management Accounting,” Management Accounting 72, no. 7 (1994): 22.

| Traditional Costing | Supply Chain Costing | |

|---|---|---|

| Objective |

|

|

| Focus |

|

|

| Cost objects |

|

|

| Cost drivers |

|

|

| Linkages |

|

|

| Precision |

|

|

| Scope |

|

|

| Visibility |

|

|

Focus

Traditional costing accumulates expenses by responsibility center. Budgets are used to compare planned versus actual expenses for variance analysis, and the responsible manager is held accountable for performance. Problems often arise because many factors beyond the manager's direct control determine the actual expense incurred. For example, a large downstream customer may arbitrarily elect to order more frequently, but in smaller quantities to reduce its average inventory levels. The total case volume moving through the manager's responsibility center does not change, but the increased number of orders may greatly increase order processing, resulting in actual expenses exceeding the budgeted expenses.

Supply chain costing addresses this problem by determining the costs associated with the processes spanning both firms. In this instance, order fulfillment costs may increase for the supplier but decrease for the customer. However, if collaboration occurs within the demand management process, the supplier may obtain decreased costs in the manufacturing flow process due to smoother demand patterns. Supply chain costing would reveal the cost trade‐offs occurring at the supplier‐customer trading partner interface and identify how managers' decisions affected costs in both firms. Traditional costing would only indicate that costs in one responsibility center (order processing) increased, and analysis would show that this was due to a customer altering a business practice.

Cost Objects

Traditional costing assigns costs by responsibility cost centers (functions or departments) or by products. However, the product alone generally does not create value for the customer. Instead, the services bundled around the product differentiate the supplier and create additional value for the customer. The customer may value the ability to customize the product, its availability, tracking, and tracing; the ability to order frequently; and the ability to depend on quick and reliable delivery. Tracking costs by product does not capture these costs or the costs incurred to serve specific customers.

Supply chain costing provides multiple views of how costs are consumed. In addition to assigning costs by products, costs can be viewed by customer or market segment, by supplier, by distribution channel, or by supply chain. The use of multiple cost drivers enables managers to view how differences between cost objects affect activity and process costs within and across firms.

Cost Drivers

The cost drivers used in traditional costing approaches involve a limited number of simple volume measures to allocate the costs that fail to capture the complexity occurring in most firms and supply chains. Some firms use the number of cases produced to allocate production costs and cases shipped to allocate distribution and marketing costs. This cost allocation factor violates costing's causality principle: the use of this production cost driver assumes manufacturing costs vary in direct proportion to the volume produced for all products. The use of a single cost driver fails to recognize differences in setup times, processes that may incur different costs, or packaging and handling differences within the production line. A similar situation exists in distribution and marketing. The cost driver assumes that marketing and logistics costs vary directly with the cases sold to customers. The use of a single driver ignores differences in lot sizes, transportation mode, distance traveled, order frequency, number of sales calls and effort, promotional spend, or customer service.

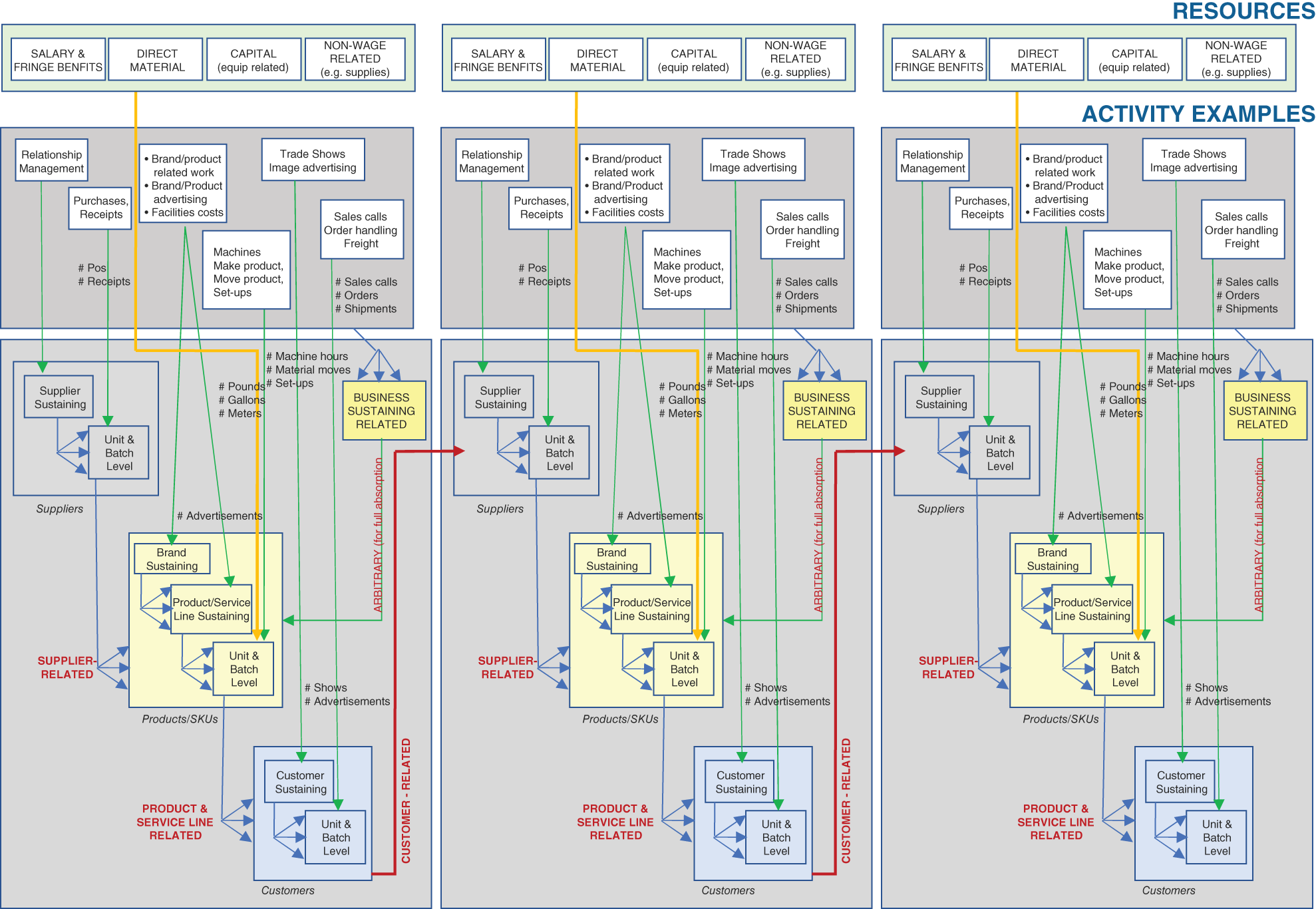

Supply chain costing uses multiple cost drivers to recognize the complexity found in most supply chains. Decision support hinges on the quality of information available for actual costs of key tasks and processes based on the resources consumed. Exhibit 5.3 illustrates how this data may be obtained. Supply chain decision makers need accurate and detailed information to analyze performance within a single firm or processes spanning multiple firms. This information cannot be obtained without the use of multiple cost drivers with the ability to trace both direct and indirect costs. Since many supply chain functions are aggregated under sales, general and administrative (SG&A), or other indirect categories, the use of cost drivers for assigning indirect costs is especially important. Without cost information and knowing what drives these costs at the activity level, supply chain managers will have no visibility regarding costs except at a very aggregate and unmanageable level.

Linkages, Precision, Scope, and Visibility

Supply chain management involves many complex linkages and relationships between sequential process steps, business units, and trading partners. These linkages involve the performance of several activities that affect cost and performance. Competitive advantages result from how well these activities are performed or how key interfaces are managed across the supply chain. Traditional costing ignores these linkages and does not provide cost information that indicates how well the supply chain is performing. Cost allocations are used to reflect any interdependencies. For example, customer service costs may be allocated based on sales volume to reflect the support provided to different customers. However, the allocation based on volume may not reflect the level of support actually provided or may mask problems occurring across the supplier–customer interface.

EXHIBIT 5.3 How Costs are Consumed Within the Supply Chain

Source: Adapted from Gary Cokins, Activity‐Based Cost Management An Executive's Guide (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2001), p. 169. Copyright Gary Cokins. Used with permission of the author.

Supply chain costing explicitly recognizes the linkages occurring in the supply chain. Costs are traced to the processes or activities within these links so managers can identify how the business practices structured within the product service agreements (PSAs) between buyers and sellers are driving costs. If behavior changes, the resulting cost information will reflect this modified behavior.

Traditional costing provides a false sense of precision. For example, using cases shipped to allocate distribution costs suggests a high level of precision for case processing costs. Managers can determine, and frequently quote, the cost per case to several decimal points. However, they cannot explain how product or customer differences may affect case processing costs. Managers frequently perceive a lower level of precision with supply chain costing due to the use of multiple cost drivers that also involve some averaging. For example, the cost of the sales force making sales calls to customers may vary based on the travel distance, size of the order taken, or type of customer account. Multiple cost drivers will probably be derived based on an analysis of these factors. Despite the additional insight into what drives sales costs, managers perceive a lower level of precision due to the differences that cannot be fully captured even with the use of multiple activities and cost drivers. However, the analysis of supply chain costs highlights important information regarding what causes costs to differ and indications of expected cost changes in the future. The question for managers becomes whether it is better to be “precisely wrong” or “imprecisely correct” in their understanding of what drives costs.

A key difference between traditional and supply chain costing is the scope of cost information captured and made visible to management. Traditional costing only captures costs internal to the firm. In most instances, the information does not indicate how changes in the behavior of trading partners affects costs internal to the firm or externally in the supply chain. Supply chain costing extends the scope of cost information available to management. Supply chain costing determines not only the firm's internal costs but costs by firm and supply chain process.

Traditional costing provides limited cost visibility and insight for managers. The use of a limited set of cost drivers and objects provides only partial information regarding what factors are actually driving costs in the firm. Since the scope of information is constrained to the firm, management does not receive any information regarding how trading partners affect the costs incurred by the firm, and, equally important, how the firm affects costs elsewhere in the supply chain.

Supply chain costing provides significantly greater transparency of the relationship between management decisions and costs. The use of multiple cost drivers enables managers to recognize how their decisions affect costs, not only within their firm, but across the supply chain. The scope of cost information extends their line of sight beyond the boundaries of their firm so they can understand how their actions affect trading partners' costs and total supply chain costs. This visibility enables managers to make effective and intelligent cost trade‐offs across multiple firms to lower overall supply chain costs. By creating more value for the end user, the trading partners will be rewarded with additional follow‐on sales and larger market share.